Hearing Loss in Chronic Kidney Disease: An Assessment of Multiple Aetiological Parameters

Received: 27-Feb-2020 / Accepted Date: 17-Apr-2020 / Published Date: 24-Apr-2020 DOI: 10.4172/2161-119X.1000393

Abstract

Background: Hearing loss in chronic kidney disease (CKD) is believed to be of multifactorial aetiology resulting from electrolytes imbalance, hypertension and diabetes.

Aim: This study aimed to correlate hearing thresholds of CKD patients with multiple parameters such as serum levels of creatinine, urea, sodium, chloride, potassium and bicarbonate, and packed cell volume, hypertension,

diabetes and duration of CKD.

Methods: This was a prospective study of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). Ethical approval and informed consent were obtained before enrolment. Patients were recruited using convenience sampling technique.

Using a health questionnaire, a brief ENT history was obtained and pure tone audiometry was carried out. Blood samples were collected prior to audiometric evaluation. Data collected was analysed using SPSS version 20.

Results: Sixty CKD patients were studied. The age range was 20-68 years with mean (SD) age of 43.2(13.4) years and 70.0% (42/60) were males. There was a positive correlation between hearing thresholds and systolic

blood pressure (r=0.2, p=0.04) and diastolic blood pressure (r=0.3, p<0.001). Similarly, there was statisticallysignificant correlation between hearing threshold and duration of CKD, packed cell volume, serum creatinine,

sodium and bicarbonate. However, there was no statistically significant correlation between hearing threshold and serum urea, chloride and potassium.

Conclusion: This study found that longer duration of CKD, elevated systolic and diastolic blood pressure, elevated serum creatinine, low packed cell volume and low levels of serum sodium and bicarbonate are strong

factors affecting hearing thresholds in patients with CKD.

Keywords: Chronic kidney disease; Electrolytes; Hearing loss; Hypertension

Introduction

There are numerous potential causes of chronic kidney disease in sub-Saharan Africa, making disease of the kidney particularly burdensome in the region. Chronic kidney disease can be caused by either communicable or non-communicable diseases; most common non-communicable disease causes of CKD include hypertension and diabetes while infectious glomerulonephritis, Human Immune- Deficiency Virus (HIV) infection, Leishmaniasis and Schistosomiasis are common communicable diseases that cause CKD. These causes of CKD are very common in sub-Saharan Africa; for instance, HIV alone affects more than 22.0 million people in sub-Saharan Africa [1,2]. This makes the burden of CKD in the region overwhelmingly high [2].

Disease of the kidney simulates disease-associated loss of renal parenchyma making the kidney to develop a compensatory adaptation by increasing blood flow and glomerular hyperfiltration that maintain function at increased levels per nephron, leading to hypertrophy of glomeruli and tubules. As a consequence of these adaptations, kidneys structure and function deteriorate steadily, reaching an end-stage renal failure within months [3]. It has been found that hyper filtration and hypertension of the glomeruli are the major contributing factors to the deterioration of CKD [3]. As per tubular vasculature underlies glomerular circulation, some mediators of glomerular inflammatory reaction inflammatory reaction frequently recorded in glomerular disease [4,5]. Any decrease in preglomerular omay overflow into the peritubular circulation contributing to the interstitial r glomerular perfusion leads to decrease in peritubular blood flow, which, depending on the degree of hypoxia, entails tubulointerstitial injury and tissue remodelling: thus, the concept of the nephron as a functional unit applies not only to renal physiology, but also to the pathophysiology of renal diseases [4,5].

Studies have shown that electrolytes imbalance, hypertension, and diabetes are the major causes and risk factors of hearing impairment in patients with chronic renal failure. Available studies have shown that based on auditory brainstem audiometry findings, the main site of lesion is cochlear and to some extent, retro-cochlear [6-11]. However, lack of correlation between blood measures and hearing function hinders a detailed explanation of the mechanism causing hearing impairment in CKD [7]. Getland et al. [7] tried to explain that, on the basis that low tone SNHL is known to be a feature of endolymphatichydrops and that hydrops is influenced by fluid balance (the glycerol dehydration test) and suggest that it is possible that endolymphatichydrops may be part of the pathological process [12].

Some studies have shown that patients with long standing renal disease had higher chances of acquiring hearing impairment than the healthy controls even after excluding other risk factors such as hypertension, electrolyte abnormalities, diabetes and proteinuria. However, there is paucity of literature on possible causes of hearing loss among adult patients with chronic kidney disease in our environment [9,13]. This study aimed to correlate hearing thresholds of CKD patients with multiple parameters such as serum levels of creatinine, urea, sodium, chloride, potassium and bicarbonate, and packed cell volume, hypertension, diabetes and duration of CKD.

Participants and Methods

Convenience sampling technique was used and sample size was calculated using Fisher ’ s formula: n=Z2pq/d2 where p=prevalence (3.6%), q=p-1, Z=standard normal deviate, which is 1.96 at 95% confidence interval and d=degree of precision at 95% confidence interval [14]. Thus: n=(1.96)2×0.036×0.964/(0.05)2=53plus 10% attrition (53/100×10=5.3). The minimum sample size required for this study was 58; however, the figure was rounded to 60. Information on demography, history, examination and pure tone audiometry were carried out. This study recruited patients with chronic kidney disease (i.e. GFR=59 ml/min/1.73m2 and below), regardless of whether they were newly diagnosed or were on follow-up visits. Blood samples for levels of serum creatinine, urea, sodium, potassium, chloride and bicarbonate, and packed cell volume were collected prior to audiometric evaluation.

Those with stageI and II kidney disease (i.e. GFR=60 ml/min/ 1.73m2 and above), and patients with history of ear disease, exposure to loud noise, and those who were too ill to undergo an audiometric test and those with type B or C tympagrams were excluded from the study.

The pure tone audiometry was carried out using a Diagnostic Audiometer (Model Graphic digi-IS, USA), calibrated to ISO standard. The test was carried out in the quietest room in the hospital where the mean ambient noise level of the test room was 33.2dB (less than 40dB) using a calibrated sound pressure level meter, Model TES1350A made in Taiwan [15].

The patients that were tested were seated on a chair in the test room and the procedure was clearly explained to each patient before commencement. The patients wore the headphones and signified on hearing the tone by pressing on a small hand-held button as soon as the tone was heard. Pure tones were delivered to each ear consecutively through the ear phones to test for air conduction (AC). The duration of presentation was two to three seconds. Both ears were tested for hearing impairment.

The test was first conducted for the right ear at 1KHz, then 2KHz, 4KHz, 6KHz, 8KHz, then 0.5KHz and 0.25KHz in that order. The test started at 40dB HL, if audible then was reduced in 10dB steps till no response occurred, then it was increased in 5dB steps till a response occurred and the results were plotted [16,17]. The left ear was then tested and the same process for air conduction was repeated. For bone conduction (BC) test, the bone vibrator was placed on the mastoid bone of the test ear (the worse ear on AC) delivering different tones for each of the speech frequencies (0.5, 1, 2, 4 KHz) [16,17]. The results of the audiometric tests for each ear were recorded separately on an audiogram [16, 17]. For air-conduction test, frequencies recorded include 0.25-8 KHz while for bone-conduction test, the frequencies recorded include 0.5-4 KHz. The pure tone average was calculated for each ear at speech frequencies of 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 KHz [16,17].

The classification of hearing threshold was as follows; Normal threshold (≤ 25 dB), mild hearing loss (26-40 dB), moderate hearing loss (41-55 dB), moderately-severe hearing loss (56-70 dB), severe hearing loss (71-91 dB) and profound hearing loss (>91 dB). All those with 25dBHL or less were considered to have normal hearing thresholds while those with more than 25dBHL were considered to have abnormal hearing thresholds [6-18]. The hearing-threshold of the patients were then compared with the various haematological indices.

The data was analysed using the Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) software IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20 (IBM Corp, Armonk, N.Y, USA). Pearson’s correlation and Chi-square test were used for statistical

Results

Sixty chronic kidney disease patients were studied. The minimum age of the patients was 20 and the maximum was 68 years with mean (SD) age of 43.2(13.4) years. Forty-two (70.0%, 42/60) were males and 18/60 (30.0%) were females with a male: female ratio of 2.3:1(see Table 1).

Tables

| Age group | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| 18-27 years | 10 | 16.7 |

| 28-37 years | 10 | 16.7 |

| 38-47 years | 18 | 30.0 |

| 48-57 years | 13 | 21.7 |

| 58 years and above | 9 | 15.0 |

| Total | 60 | 100 |

| Sex | ||

| Males | 42 | 70.0 |

| Females | 18 | 30.0 |

| Total | 60 | 100 |

Table 1: Age and sex distribution of participants.

Fifty-one (68.3%, 41/60) of the patients were hypertensive.

Table 2 showed subjects with hypertension with or without hearing loss and those without hypertension with or without hearing loss.

| Hearing Threshold | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal ( ≤ 25dBHL) | Abnormal (>25dBHL) | ||||

| Hypertension | Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent | Total |

| Hypertensive | 21 | 41.2 | 30 | 58.8 | 51(100%) |

| Not hypertensive | 5 | 55.6 | 4 | 44.4 | 9(100%) |

Table 2: Hearing threshold versus blood pressure

The minimum systolic blood pressure (SBP) was 110 mmHg and the maximum was 210 mmHg with mean (SD) SBP of 159.0(21.1) mmHg. Pearson correlation showed a weak positive relationship between SBP and hearing threshold and was statistically significant (r=0.2, p=0.04). The diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ranged between 70 and 120 mmHg with a mean (SD) DBP of 99.8(12.3) mmHg. Again, the correlation coefficients between DBP and hearing threshold revealed a weak positive relationship (r=0.3) and was statistically significant (p<0.01).

Sixteen (26.7%, 16/60) subjects had diabetes while 44 (73.3%, 44/60) subjects were not diabetic. Of the 16 subjects with diabetes, 9/16 (56.2%) had normal hearing thresholds while 7/16 (43.8%) had hearing loss. Of the 44 subjects without diabetes, 27/44 (61.4%) had hearing loss and 17/44 (38.6%) had normal hearing thresholds. The difference was not statistically significant (x2=1.5, p=0.22).

The minimum duration of diagnosis of CKD was three months and the maximum was 96 months with mean (SD) duration of 12.3(17.9) months. The Pearson correlation coefficients between hearing threshold and duration of CKD revealed that the longer the duration of CKD, the worse the hearing threshold. The correlation showed a weak positive correlation (r=0.3) and was statistically significant (p<0.01).

Table 3 shows the relationship between hearing threshold and duration of CKD.

| Duration of CKD | HT of BHE | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of CKD | Pearson Correlation | 1 | 0.294 |

| Sig (2-tailed) | 0.001 | ||

| N | 60 | 60 | |

| HT of BHE | Pearson Correlation | 0.294 | 1 |

| Sig (2-tailed) | 0.001 | ||

| N | 60 | 60 | |

Table 3: Relationship between hearing threshold and duration of CKD.

CKD=chronic kidney disease, HT=hearing threshold, BHE=better hearing ear, N=number of patients

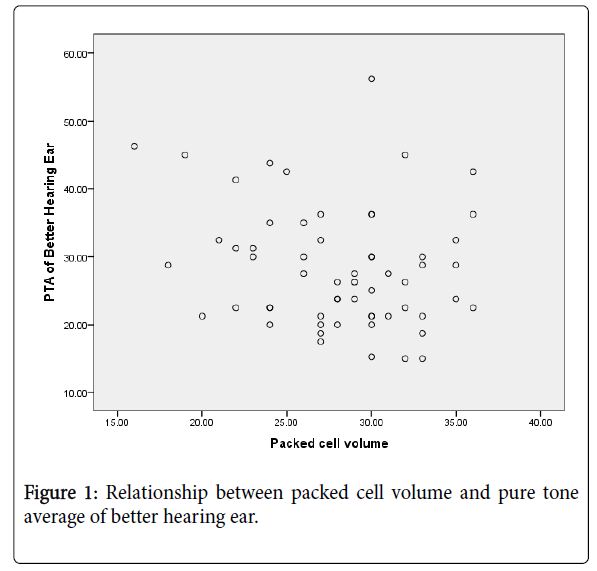

The packed cell volume (PCV) of the patients ranged between 16 and 36 percent with a mean (SD) PCV of 28.1(4.7) percent. The Pearson correlation coefficients between hearing threshold of better hearing ear and packed cell volume showed that there was a moderately negative relationship and was statistically significant (r=-0.5, p<0.001).

Figure 1 showed the relationship between PCV and hearing threshold of better hearing ear.

The serum creatinine of the patients ranged between 152 and 1797 μmol/l with a mean (SD) creatinine of 495.5(340.5) μmol/l. The Pearson correlation coefficients between hearing threshold of the better hearing ear and serum creatinine level showed that there was a moderately positive correlation (r=0.5) and was statistically significant (p<0.001).

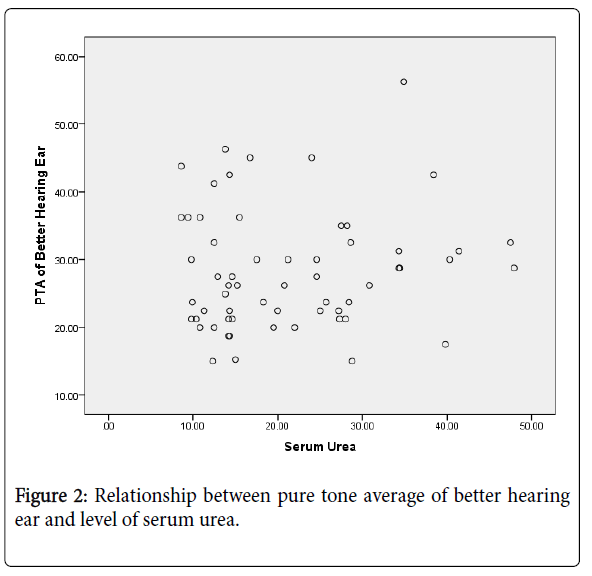

The serum urea ranged between 8.6 and 47.9 mmol/l with mean (SD) of 21.3(10.4) mmol/l. There was no statistically significant correlation between serum urea level and hearing threshold of better hearing ear (r=0.09, p=0.46).

Figure 2 shows the relationship between hearing threshold and serum urea level.

The hearing threshold of better hearing ear and serum sodium showed weak negative correlation and was statistically significant (r= -0.2, p=0.02). Similarly, serum bicarbonate and hearing threshold of better hearing ear also showed a weak negative relationship and was statistically significant (r= -0.2, p=0.04).

However, serum chloride and hearing threshold of better hearing ear showed no relationship (r = -0.03) and was not statistically significant (p=0.73). Similarly, the correlation between serum potassium and hearing threshold of better hearing ear also showed no relationship (r=0.04) and was not statistically significant (p=0.62).

Discussion

Some researchers have hypothesized that hearing impairment resulting from cochlear dysfunction could be attributed to a combination of factors such as serum creatinine levels, serum urea and fluid and electrolytes imbalance, as well as concomitant comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension [18,19].

Hypertension has been known to be a main cause or consequence of chronic kidney disease. Studies have shown that high pressure in the vascular system may cause increase in blood viscosity leading to reduction in the capillary blood flow and subsequent reduction in oxygen transport leading to cochlea hypoxia and loss of outer hair cells leading to sensor neural hearing loss [20]. In this study, 85.0% of the subjects with CKD had high blood pressure [21]. This study further showed that increased systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were significantly associated with hearing loss. Bendo et al. [13]. Also found a correlation between SBP and sensor neural hearing loss. All their patients that had SNHL had systolic blood pressure more than 160mmHg. Seo et al. [19]. In their study of association of hearing impairment with chronic kidney disease in a large Korean population found a correlation between high blood pressure and hearing impairment. They concluded that high blood pressure could be an independent contributing factor that disturbed cochlear function. Other studies that found correlation between hypertension and hearing threshold include Meena et al. [9] and Singh-Bawa et al. [22] all from India. It is to be noted however that other factors such as age and duration of CKD additionally influence the finding of hearing loss among subjects with hypertension, but generally, presence of hypertension in CKD patients may imply hearing loss is present in these subjects and obtaining audiograms become necessary in these patients.

Lasisi et al. [23] in Ibadan, South-western Nigeria, did not find any correlation between hearing thresholds and other variables such as blood pressure. The subjects used in the study were CKD patients who had not previously had haemodialysis prior to inception of the study and they assessed hearing thresholds of the patients at recruitment and after three sessions of haemodialysis. Nikolopoulos et al. [24] in Greece, Sreedharan et al. [25] in Mangalore and Esfahani et al. [26] in Iran all found no significant relationship between hypertension and sensorineural hearing loss. This may be because the subjects they studied included young persons and some included all the 5 stages (stage I to V) of kidney disease not limiting to those with CKD (stage III to V). For instance, Nikolopoulos et al. [24] studied all the 5 stages of CKD (stage I to V). Sreedharan et al. [25] studied adolescents and adult subjects, aged 14-73 years with end stage renal disease (ESRD) while Esfahani et al. [26] studied only those with ESRD.

Like hypertension, diabetes has also been known to be a major cause or consequence of chronic kidney disease. Studies have shown that sensorineural hearing loss is very common among patients with diabetes mellitus compared to the general population [1]. Diabetes is a chronic systemic disease with various pathogenic mechanisms and patients with diabetes often manifest various levels of metabolic disorders due to absolute or relative insulin deficiency leading to elevated blood glucose which is then deposited in the walls of small blood vessels [27]. This leads to endothelial injury by immune complex leading to increased permeability, thickening of basement membrane and abnormal growth of endothelial cells, resulting in reduced lumen size of the blood vessels [27]. With blocked or reduced supplying vessels and sustained high glucose levels, nerves become malnourished leading to necrosis or dysplastic changes from metabolic disorders and this subsequently leads to diabetic peripheral neuropathy [27]. These vascular and neural changes together with high levels of blood glucose cause injury to the cochlea due to thickening of the capillary walls of the cochlea (especially in the striavascularis) and loss of outer hair cells leading to sensorineural hearing loss [27,28].

In this study, 26.7% of the subjects with CKD had diabetes and the remaining 73.3% of the patients were not diabetic. Of those with diabetes, 46.9% had hearing loss. When compared to those without diabetes mellitus, there was no statistically significant difference in the occurrence of hearing loss among the patients (p=0.156). Jamaldeen et al. [8]similarly did not find significant difference between CKD subjects with diabetes having hearing loss and CKD subjects with diabetes without hearing loss. Sreedharan et al. [25] also found no significant statistical difference between CKD patients with and without diabetes, and hearing impairment. However, Lin et al. [10] in their study observed a synergistic effect between chronic kidney disease and diabetes and occurrence of sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Similarly, Seo et al. [19] in their study reported significant association between diabetes and hearing loss in patients with CKD.

This study showed worsening of hearing thresholds with increasing duration of CKD (r=0.294, p=0.001). Bendo and colleagues, in their study of hearing evaluation in patients with chronic renal failure also reported similar finding and they concluded that the longer the duration of CKD, the worse the degree of SNHL [13]. However, Sharma et al. [18] in their study found that there was no correlation between duration of CKD and hearing threshold and they concluded that deafness is an early phenomenon in patients with CKD and the deafness does not progress further with duration of the disease. Similarly, Reddy et al. [6] and Sam et al. [29] found no significant correlation between hearing loss and duration of CKD. Henrich et al. [30] in their study also showed no deterioration in hearing thresholds in 75.0% of the patients during a four-year follow up. They however, did not give any explanation as to why there was no correlation between hearing loss and duration of diagnosis of CKD.

Anaemia is a common complication of chronic kidney disease [31]. This study showed that the packed cell volume (PCV) tend to be negatively associated with hearing loss (i.e. the lower the packed cell volume, the higher the hearing loss). The correlation between PCV and pure tone average showed that there was moderately negative relationship and was statistically significant (r=-0.461, p<0.001). Sreedharan et al. [25] also reported negative correlation between PCV and hearing loss in patients with CKD. However, Reddy et al. [6] and Kusakari et al. [32] in their studies found no significant correlation between hearing loss and haemoglobin level. Available literature revealed that low packed cell volume can lead to decrease in blood supply to the inner ear which is highly sensitive to ischemic damage leading to cochlear dysfunction [33].

Studies have shown that hearing loss increases with increasing level of serum creatinine (decreasing GFR) in patients with CKD. This current study showed that there was a moderately positive correlation between serum creatinine level and hearing threshold (r=0.510) and this was statistically significant (p<0.001) [19-34]. Lasisi et al. [23] in Ibadan, Nigeria in their study of effect of haemodialysis on the hearing function of patients with chronic renal failure also found a significant correlation between serum creatinine level and pure tone thresholds. Also, Seo et al. [19] in Korea in their study of association of hearing impairment with chronic kidney disease found a correlation between high level of serum creatinine and hearing impairment and they concluded that serum creatinine could be an independent factor contributing to cochlear dysfunction. Sreedharan and co-workers similarly found a correlation between hearing loss and serum creatinine level [25]. However, Reddy and colleagues, in their study of proportion of hearing loss in chronic renal failure found no significant correlation between hearing loss and serum creatinine level [6]. In their study, patients enrolled were not limited to those with CKD, rather all patients with renal disease (stage I to V) were enrolled; this may have resulted in the failure to find correlation between hearing loss and creatinine level. Furthermore, they included much younger age group in their study (15 years and above).

Although high blood urea has been suggested as possible factor that contribute to hearing acuity deterioration in subjects with chronic kidney disease, [34,35] this current study however found no correlation between serum urea and pure tone average among CKD patients. Reddy et al. [6] also found no significant correlation between hearing loss and serum urea level. Similarly, Bendo et al. [13] reported in their study that the increase level of serum urea and creatinine could not predict the occurrence of SNHL. Also, Kusakari et al. [32] Saeed et al. [35] and Somashekara et al. [36] in their different studies did not find any significant correlation between serum creatinine or urea level and hearing loss. However, Sreedharan and colleagues, in their study of hearing loss in chronic renal failure found a positive correlation between hearing loss and serum urea level [25].

Other parameters that showed significant correlation with hearing loss in this study include serum sodium which showed weak negative relationship and serum bicarbonate which also revealed weak negative relationship. Somashekara et al. [36] also found a correlation between hearing loss and serum sodium. However, Saeed and colleagues, found no correlation between serum sodium and hearing loss [35]. The difference in methodology used, theirs being longitudinal study may explain the contrast between the findings in their study and this study. Furthermore, they studied only patients with stage 5 kidney disease. Generally however, Chronic kidney disease is characterized by disturbed sodium, potassium blood levels and this may result in poor coupling of energy from the stapes footplate to the hair cells [25]. Some studies have suggested that the degree of hearing impairment in CKD is directly related to the degree of hyponatremia [25].

However, this study found no correlation between serum chloride and serum potassium and hearing loss. Saeed et al. [35] and Somashekara et al. [36] found no correlation between hearing loss and serum chloride and potassium. However, Sreedharan et al. [25] found a negative correlation between hearing loss and serum potassium. They however studied only subjects with end stage renal disease.

Discussion

Some researchers have hypothesized that hearing impairment resulting from cochlear dysfunction could be attributed to a combination of factors such as serum creatinine levels, serum urea and fluid and electrolytes imbalance, as well as concomitant comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension [18,19].

Hypertension has been known to be a main cause or consequence of chronic kidney disease. Studies have shown that high pressure in the vascular system may cause increase in blood viscosity leading to reduction in the capillary blood flow and subsequent reduction in oxygen transport leading to cochlea hypoxia and loss of outer hair cells leading to sensor neural hearing loss [20]. In this study, 85.0% of the subjects with CKD had high blood pressure [21]. This study further showed that increased systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were significantly associated with hearing loss. Bendo et al. [13]. Also found a correlation between SBP and sensor neural hearing loss. All their patients that had SNHL had systolic blood pressure more than 160mmHg. Seo et al. [19]. In their study of association of hearing impairment with chronic kidney disease in a large Korean population found a correlation between high blood pressure and hearing impairment. They concluded that high blood pressure could be an independent contributing factor that disturbed cochlear function. Other studies that found correlation between hypertension and hearing threshold include Meena et al. [9] and Singh-Bawa et al. [22] all from India. It is to be noted however that other factors such as age and duration of CKD additionally influence the finding of hearing loss among subjects with hypertension, but generally, presence of hypertension in CKD patients may imply hearing loss is present in these subjects and obtaining audiograms become necessary in these patients.

Lasisi et al. [23] in Ibadan, South-western Nigeria, did not find any correlation between hearing thresholds and other variables such as blood pressure. The subjects used in the study were CKD patients who had not previously had haemodialysis prior to inception of the study and they assessed hearing thresholds of the patients at recruitment and after three sessions of haemodialysis. Nikolopoulos et al. [24] in Greece, Sreedharan et al. [25] in Mangalore and Esfahani et al. [26] in Iran all found no significant relationship between hypertension and sensorineural hearing loss. This may be because the subjects they studied included young persons and some included all the 5 stages (stage I to V) of kidney disease not limiting to those with CKD (stage III to V). For instance, Nikolopoulos et al. [24] studied all the 5 stages of CKD (stage I to V). Sreedharan et al. [25] studied adolescents and adult subjects, aged 14-73 years with end stage renal disease (ESRD) while Esfahani et al. [26] studied only those with ESRD.

Like hypertension, diabetes has also been known to be a major cause or consequence of chronic kidney disease. Studies have shown that sensorineural hearing loss is very common among patients with diabetes mellitus compared to the general population [1]. Diabetes is a chronic systemic disease with various pathogenic mechanisms and patients with diabetes often manifest various levels of metabolic disorders due to absolute or relative insulin deficiency leading to elevated blood glucose which is then deposited in the walls of small blood vessels [27]. This leads to endothelial injury by immune complex leading to increased permeability, thickening of basement membrane and abnormal growth of endothelial cells, resulting in reduced lumen size of the blood vessels [27]. With blocked or reduced supplying vessels and sustained high glucose levels, nerves become malnourished leading to necrosis or dysplastic changes from metabolic disorders and this subsequently leads to diabetic peripheral neuropathy [27]. These vascular and neural changes together with high levels of blood glucose cause injury to the cochlea due to thickening of the capillary walls of the cochlea (especially in the striavascularis) and loss of outer hair cells leading to sensorineural hearing loss [27,28].

In this study, 26.7% of the subjects with CKD had diabetes and the remaining 73.3% of the patients were not diabetic. Of those with diabetes, 46.9% had hearing loss. When compared to those without diabetes mellitus, there was no statistically significant difference in the occurrence of hearing loss among the patients (p=0.156). Jamaldeen et al. [8]similarly did not find significant difference between CKD subjects with diabetes having hearing loss and CKD subjects with diabetes without hearing loss. Sreedharan et al. [25] also found no significant statistical difference between CKD patients with and without diabetes, and hearing impairment. However, Lin et al. [10] in their study observed a synergistic effect between chronic kidney disease and diabetes and occurrence of sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Similarly, Seo et al. [19] in their study reported significant association between diabetes and hearing loss in patients with CKD.

This study showed worsening of hearing thresholds with increasing duration of CKD (r=0.294, p=0.001). Bendo and colleagues, in their study of hearing evaluation in patients with chronic renal failure also reported similar finding and they concluded that the longer the duration of CKD, the worse the degree of SNHL [13]. However, Sharma et al. [18] in their study found that there was no correlation between duration of CKD and hearing threshold and they concluded that deafness is an early phenomenon in patients with CKD and the deafness does not progress further with duration of the disease. Similarly, Reddy et al. [6] and Sam et al. [29] found no significant correlation between hearing loss and duration of CKD. Henrich et al. [30] in their study also showed no deterioration in hearing thresholds in 75.0% of the patients during a four-year follow up. They however, did not give any explanation as to why there was no correlation between hearing loss and duration of diagnosis of CKD.

Anaemia is a common complication of chronic kidney disease [31]. This study showed that the packed cell volume (PCV) tend to be negatively associated with hearing loss (i.e. the lower the packed cell volume, the higher the hearing loss). The correlation between PCV and pure tone average showed that there was moderately negative relationship and was statistically significant (r=-0.461, p<0.001). Sreedharan et al. [25] also reported negative correlation between PCV and hearing loss in patients with CKD. However, Reddy et al. [6] and Kusakari et al. [32] in their studies found no significant correlation between hearing loss and haemoglobin level. Available literature revealed that low packed cell volume can lead to decrease in blood supply to the inner ear which is highly sensitive to ischemic damage leading to cochlear dysfunction [33].

Studies have shown that hearing loss increases with increasing level of serum creatinine (decreasing GFR) in patients with CKD. This current study showed that there was a moderately positive correlation between serum creatinine level and hearing threshold (r=0.510) and this was statistically significant (p<0.001) [19-34]. Lasisi et al. [23] in Ibadan, Nigeria in their study of effect of haemodialysis on the hearing function of patients with chronic renal failure also found a significant correlation between serum creatinine level and pure tone thresholds. Also, Seo et al. [19] in Korea in their study of association of hearing impairment with chronic kidney disease found a correlation between high level of serum creatinine and hearing impairment and they concluded that serum creatinine could be an independent factor contributing to cochlear dysfunction. Sreedharan and co-workers similarly found a correlation between hearing loss and serum creatinine level [25]. However, Reddy and colleagues, in their study of proportion of hearing loss in chronic renal failure found no significant correlation between hearing loss and serum creatinine level [6]. In their study, patients enrolled were not limited to those with CKD, rather all patients with renal disease (stage I to V) were enrolled; this may have resulted in the failure to find correlation between hearing loss and creatinine level. Furthermore, they included much younger age group in their study (15 years and above).

Although high blood urea has been suggested as possible factor that contribute to hearing acuity deterioration in subjects with chronic kidney disease, [34,35] this current study however found no correlation between serum urea and pure tone average among CKD patients. Reddy et al. [6] also found no significant correlation between hearing loss and serum urea level. Similarly, Bendo et al. [13] reported in their study that the increase level of serum urea and creatinine could not predict the occurrence of SNHL. Also, Kusakari et al. [32] Saeed et al. [35] and Somashekara et al. [36] in their different studies did not find any significant correlation between serum creatinine or urea level and hearing loss. However, Sreedharan and colleagues, in their study of hearing loss in chronic renal failure found a positive correlation between hearing loss and serum urea level [25].

Other parameters that showed significant correlation with hearing loss in this study include serum sodium which showed weak negative relationship and serum bicarbonate which also revealed weak negative relationship. Somashekara et al. [36] also found a correlation between hearing loss and serum sodium. However, Saeed and colleagues, found no correlation between serum sodium and hearing loss [35]. The difference in methodology used, theirs being longitudinal study may explain the contrast between the findings in their study and this study. Furthermore, they studied only patients with stage 5 kidney disease. Generally however, Chronic kidney disease is characterized by disturbed sodium, potassium blood levels and this may result in poor coupling of energy from the stapes footplate to the hair cells [25]. Some studies have suggested that the degree of hearing impairment in CKD is directly related to the degree of hyponatremia [25].

However, this study found no correlation between serum chloride and serum potassium and hearing loss. Saeed et al. [35] and Somashekara et al. [36] found no correlation between hearing loss and serum chloride and potassium. However, Sreedharan et al. [25] found a negative correlation between hearing loss and serum potassium. They however studied only subjects with end stage renal disease.

Conclusion

This study found that longer duration of CKD, elevated systolic and diastolic blood pressure, elevated serum creatinine, low packed cell volumeand low levels of serum sodium and bicarbonate are strong factors affecting hearing thresholds in patients with CKD while diabetes mellitus, serum urea, chloride and potassium were not found to be significant factors affecting hearing acuity of patients with CKD.

Financial Support/Sponsorship

No Funding

Conflict of Interest

None

References

- Ibrahim BC, Amali MA, Isah UA, Michael SO, Ramada AM. (2015) Demographic characteristics and causes of chronic kidney disease in patients receiving hemodialysis at IBB Specialist Hospital Minna, Niger State, Nigeria. J Med Medical Res 3:21-26.

- Stanifer J, Jing B, Tolan S, Helmke N, Mukerjee R, et al. ( 2014) The epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2:174-181.

- Venkatachalam MA, Grif?n KA, Lan R, Geng H, Saikumar P, et al. (2010) Acute kidney injury: a springboard for progression in chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298:1078-1094.

- Matovinovi? MS. (2009) Pathophysiology and Classificatrion of Kidney Diseases. J Int Fed ClinChem Lab Med 20:1-10.

- Odubanjo MO, Okolo CA , Oluwasola AO, Arije A. (2011) End-Stage Renal Disease in Nigeria: An Overview of the Epidemiology and the Pathogenetic Mechanisms. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 22:1064-1071.

- Reddy EK, Surya Prakash DR, Rama Krishna MG. (2016) Proportion of hearing loss in chronic renal failure: Our experience. Indian J Otol 22:4-9.

- Thodi C, Thodis E, Danielides V, Pasadakis P, Vargemezis V. (2006) Â Hearing in renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 21:3023-3030.

- Jamaldeen J, Basheer A, Sarma A, Kandasamy R. (2015) Prevalence and patterns of hearing loss among chronic kidney disease patients undergoing haemodialysis. Australian Med J 8:41-46.

- Meena R, Aseri Y, Singh B, Verma P. (2012) Hearing Loss in Patients of Chronic Renal Failure: A Study of 100 Cases. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 64:356-359.

- Lin C, Hsu H, Lin Y, Weng S. (2012) Increased risk of getting sudden sensorineural hearing loss in patients with chronic kidney disease: A population-based cohort study. Laryngoscope 123:767-773.

- Fufore MB, Kirfi AM, Salisu AD, Samdi TM, Abubakar AB, et al. (2019) Prevalence and Pattern of Hearing Loss in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease in Kaduna, Northwestern Nigeria. Indian J Otol 25:201-205.

- Gatland D, Tucker B, Chalstrey C, Keene M, Baker L. (1991) Hearing loss in chronic renal failure hearing threshold changes following haemodialysis. J R Soc 84:587-589.

- Bendo E, Resuli M, Metaxas S. (2015) Hearing evaluation in patients with chronic renal failure. J Acute Disease 4:51-53.

- Alebiosu CO, Ayodele OO, Abbas A, Olutoyin IA. (2006) Â Chronic renal failure at the OlabisiOnabanjo university teaching hospital, Sagamu, Nigeria. Afr Health Sci 6:132-138.

- Wong TW, Yu TS, Chen WQ, Chiu YL, Wong CN, et al. (2003) Agreement between hearing thresholds measured in non-sound proof work environment and a sound proof booth. Occup Environ Med 60:667-671.

- Walker JJ, Cleveland LM, Davis JL, Seales JS. (2013) Â Audiometry Screening and Interpretation. Am Fam Physician 87:41-47.

- Kirfi AM, Samdi MT, Salisu AD, Fufore MB. (2019) Hearing Threshold of Deaf Pupils in Kaduna Metropolis, Kaduna Nigeria: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Niger Postgrad Med J 26:164-168.

- Sharma R, Gautam P, Narain A, Gaur S, Tiwari R, et al. (2011) Â A study on hearing evaluation in patients of chronic renal failure. Indian J Otol 17:109-112.

- Seo Y, Ko S, Ha T, Gong T, Bong J, et al. (2015) Association of hearing impairment with chronic kidney disease: a cross-sectional study of the Korean general population. BMC Nephrol 16:1-7.

- Romao-Junior JE. (2004) Chronic kidney disease: definition, epidemiology, and classification. J Bras Nephrol 2004;26:1-263.

- Ohinata Y, Makimoto K, Kawakami M, Takahashi H. (1994) Blood viscosity and plasma viscosity in patients sudden deafness. Acta Otolaryngol 114:601-607.

- Singh-Bawa A, Singh G, Uzair G, Garg S, Kaur J. (2017) Â Pattern of hearing loss among chronic kidney disease patients on haemodialysis. Int J Med Res Prof 3:193-196.

- Lasisi A, Salako B, Osowole O, Osisanya W, Amusat M. (2008) Effect of hemodialysis on the hearing function of patients with chronic renal failure. Afr J Health Sci 13:29-32.

- Nikolopoulos T, Kandiloros D, Segas J, Nomicos P, Ferekidis E, et al. (1997) Â Auditory function in young patients with chronic renal failure. ClinOtolaryngol Allied Sci 22:222-5.

- Sreedharan S, Prasad S, Bhat J, Chandra M, Salil H, et al. (2015) Â Hearing loss in chronic renal failure - an assessment of multiple aetiological factors. J Otolaryngol 5:1-10.

- Esfahani ST, Madani A, Ataei N, Tehrani AN, Mohseni P, et al. (2004) Â Sensorineural hearing loss in children with end-stage renal disease. Acta Med Iranica 42:375-378.

- Xipeng L, Ruiyu L, Meng L, Yanzhuo Z, Kaosan G, e al. (2013) Â Effects of diabetes on hearing and cochlear structures. J Otol 8:82-87.

- Fukushima H, Cureoglu S, Schachern PA, Kusunoki T, Oktay MF, et al. (2005) Cochlear changes in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 133:100-106.

- Sam SK, Subramaniam V, Pai S, Kallikkadan HH. (2014) Â Hearing impairment in patients with chronic renal failure. J Med SciClin Res 2:406-416.

- Henrich W, Thompson P, Bergstrom L, Lum GM. (1977) Â Effect of dialysis on hearing acuity. Nephron 18:348-351.

- Drüeke TB, Locatelli F, Clyne N, Eckardt K, Macdougall IC, et al. (2006) Normalization of Hemoglobin Level in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease and Anemia. N Engl J Med 355:2071-2084.

- Kusakari J, Kobayashi T, Rokugo M, Arakawa E, Ohyama K, et al. (1981) The inner ear dysfunction in haemodialysis patients. Tohoku J Exp Med 135:359-369.

- Schieffer KM, Chuang CH, Connor J, Pawelczyk JA, Sekhar DL. (2017) Iron Deficiency Anemia is Associated with Hearing Loss in the Adult Population. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 143:350-354.

- Govender S, Govender C, Matthews G. (2013) Cochlear function in patients with chronic kidney disease. S Afr J Comm Dis 60:44-49.

- Saeed HK, Al-Abbasi AM, Al-Maliki SK, Al-Asadi JN.(2018) Sensorineural hearing loss in patients with chronic renal failure on hemodialysis in Basrah, Iraq. Ci Ji Yi Xue Za Zhi.30:216-220.

- Somashekara KG, ChandreGowda BV, Smitha SG, Mathew AS. (2015) Etiological evaluation of hearing loss in chronic renal failure. Indian J Basic Appl Med Res.4:194-194.

Citation: Fufore MB, Kirfi AM, Salisu AD, Samdi TM, Abubakar Ab et al. (2020) Hearing Loss in Chronic Kidney Disease: An Assessment of Multiple Aetiological Parameters. Otolaryngol 10: 1000393. DOI: 10.4172/2161-119X.1000393

Copyright: © 2020 Fufore MB, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Hearing Loss in Chronic Kidney Diseases.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 2846

- [From(publication date): 0-2020 - Apr 05, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 2093

- PDF downloads: 753