Functional Appliances in the Treatment of Sleep Apnea in Children: A Systematic Review

Received: 01-Sep-2015 / Accepted Date: 05-Oct-2015 / Published Date: 11-Oct-2015 DOI: 10.4172/2161-119X.1000212

Abstract

Obstructive Sleep Apnea in children (OSA) is a Sleep-Disordered Breathing (SDR) characterized by partial or complete obstruction of the Upper Airways (UA) during sleep and interfere with sleep patterns and growth and development in children. The gold standard treatment in children is the removal of lymphoid tissue surgery. Disease recurrence can happen and is believed to be due to craniofacial concomitant problems, among others. The objective of this systematic review was demonstrate the effect of the use of functional appliances in the treatment of OSA in children. The search was in the databases included "pubmed, scholar, Medline, scielo" with the filters, "human, children, in all languages, with the key words "obstructive sleep apnea and children and orthodontic appliance" between the years 1988-2015. Initially were obtained 49 studies, but only 8 studies were eligible by level of evidence. The researches presented clinical positive results but not statistical results. This systematic literature review showed that orthopaedic devices seem to be a good treatment option for children with OSA. Although the level of evidence of the effectiveness of these devices is weak to moderate.

Abbreviations

AHI: Apnea/Hypopnea Index; OSA: Obstructive Sleep Apnea; REM: Rapid Eye Movement; SDB: Sleep Disordered Breathing; UA: Upper Airways; PS: Primary Snoring; OB: Oral Breathing; PSG: Polysomnography Exam; CPAP or BPAP: Air Pressure Devices; FA: Functional Appliances

Introduction

Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA) is a breathing disorder sleep characterized by partial or complete obstruction of the Upper Airways (UA) interfering with the normal sleep pattern. The prevalence of this disease in children is 0.2 to 3% [1-4]. Children with OSA usually present insidious signs and symptoms such as Primary Snoring (PS), Oral Breathing (OB), behavioural disorders, hyperactivity daytime, which cannot be recognized as part of that disease [5-11].

The Polysomnography Exam (PSG) is considered the gold standard for diagnosis, expressed by the apnea and hypopnea index (AIH), classified according to the number of occurrences per hour of sleep: the diagnosis is confirmed when the AHI is higher than [1,12,13]. The criteria diagnostic for children are different from adults and have not been completely established yet [4]. Many studies suggest more diagnostic tools and options should be considered, such as parents reports, clinical examination, questionnaires addressing behavioral and cognitive information and 3D imaging studies [14-23]. The multi displinary and multi professional nature of the disease, recommending an interactive diagnostic approach [24-28]. Adenotonsillar hypertrophy is known to be the main risk factor for the disease [1-11] followed by obesity, neuromuscular disorders and craniofacial anomalies [29-34]. The gold standard treatment for children is removal of the oropharyngeal lymphoid tissue [9,11,30-34]. Treatment during childhood is believed to be crucial; the delay in its recognition may play a negative influence on the quality in their adult life [35-38].

The most common non-surgical types of treatment include devices of air pressure (CPAP or BPAP), however, they are expensive and little accepted by children [39,40]. Recurrence of the clinical condition can happen after adenotonsillectomy, and it is believed to be due to concomitant craniofacial problems, among others [41-43]. These alterations can be easily recognized and treated by the orthodontist [23-26]. The persistence of OB and PS during the growing and developmental period may lead or exacerbate dental skeletal changes [39,42,43]. The incurred changes coupled with genetic predisposition make the OSA even more severe, allowing the development of a vicious circle. Orthodontic appliances can be used before or after surgery as preventive or curative [5,6,34,39,42-49]. The FA is widely used in children to promote mandibular growth and to improve craniofacial changes [50-56]. The mandibular advancement devices protrude the mandible and the tongue, increasing the passage diameter of the UA, improving the tonicity of the muscles in the region, particularly the genioglossus muscle, and consequently preventing the collapse of the soft tissue [57-63].

FA offer no risks, they are well tolerated by the patients, they minimize the overall costs of the treatment and are an alternative for the children treatment with OSA who persist with the disease after surgery [42,44]. The best results are obtained when the child enters in the pubertal growth spurt [51-57]. The restriction of this treatment is the lack of children´s cooperation by not using the device properly. Good results depend on the appropriate device use, at least for 12 months, all day long [59-65]. The objective of this research was to demonstrate through a systematic review, the effectiveness of a FA in the treatment of OSA in children.

Search of Databases

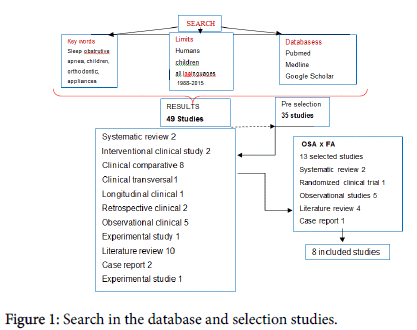

The search was in the databases included "pubmed, scholar, Medline, scielo" with the filters, "human, children, in all languages, with the key words "obstructive sleep apnea and children and orthodontic appliance" between the years 1988-2015. Initially were obtained 49 studies and 14 studies were excluded from the first selection by checking their overall goals as Osa and enuresis, OSA and syndromes. This pre-selection was made by three researchers individually. The selected 35 studies were requested by subjects in a comprehensive manner, including etiology of the disease, related to other sicknesses such as OB, PS, size of UA, diagnostic and treatment. The results of research we could see in Table 1.

| Year | Author | Subject | Evidence | N | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | Van Holsbekeet al. | OSA x 3D x FAx x resistence AU | Clinical cross | 143 | Women respond better to treatment |

| 2011 | Matter et al. | OB x NBx cephal skeletal pattern | Clinical longitudinal | 33 | Surgery restored normal growth in children pattern |

| 2007 | Vos et al. | OSA x 3D x PSG | Clinical observational | 20 | All tests should be used for effective diagnosis of OSA |

| 2006 | Ramos et al. | OSA PSG x x INDEX | Clinical observational | 93 | RA and adenoid and tonsil hypertrophy are large alerts in OSA |

| 2008 | Gregório et al. | OSA x most frequent symptoms | Clinical observational | 38 | PS, bruxism, early age appeared in children with severe OSA |

| 2011 | Godtet al. | OSA x UA x FA x Class II x HG x Rx | Clinical observational | There was no significant change in the UA after treatments | |

| 2002 | Villaet al. | OSA x FA x tolerance x results | Clinical rand controlled | 32 | FA treated group had reduced OSA and well toletou the device |

| 2013 | Gullerminoult et al. | OSA surgery x relapse | Clinical retrospective | 29 | RecidiUA in adolescents were confirmed, I need to study better |

| 2011 | Kizinger et al. | OSA x UAX Cefalom x FA | Clinical retrospective | 43 | Ap fixed not improve OSA and cephalometric does not evaluate UA |

| 1988 | Cheng et al. | OB x mallocclusion | ClinicalControlled obser | 71 | OB should be recognized early to avoid malformations |

| 2011 | Moraes ME | CBCT x 2D in dry skulls | Experimental Study | 10 | 3D survey looks better than 2D on dry skulls |

| 2005 | Nixon et al. | OSA diagnostic x | Literature review | Importance of early diagnosis of the disease to prevent greater evils | |

| 2009 | Capua, Ahmadi, Shapiro | OSA and growth | Literature review | OSA has cognitive and functional negative impact | |

| 2011 | Shott | OSA Persistent x risk factors | Literature review | Risk factors for persistent OSA | |

| 2006 | Gozzaland Gozzal | OSA diagnostic | Literature review | Because of the multifactorial nature of the disease there is no rule to day | |

| 2013 | Chen e Lowe | OSA x FA | Literature review | Are effective but lack methods for real evidence | |

| 2012 | Villa, Miano e Rizzoli | OSA x FA x tonsillectomy | Literature review | Both methods are effective but the FA seems to be more efficient | |

| 2012 | Pliska e Almeida | OSA x x FA treatment | Literature review | FA are the first choice for mild to moderate OSA for effectiveness | |

| 2013 | Tapia e Marcus | OSA x Obesity and risk | Literature review | Obese child remains with OSA, and new hair salon should be applied | |

| 2001 | Guilleminault e Quo | OSA x FA | Literature review | Importance of dentists and orthodontists for treatment options | |

| 1990 | Guilleminault e Stoohs | OSA HS x x B x PSG | Literature review | Importance of recognizing and treating these diseases | |

| 2015 | Huynh et al. | OSA x FA x ERM | Systematc review | Without consistens results | |

| 2007 | Carvalho et al. | OSA x FA | Systematic review | No enough evidence in the treatment of OSA with FA |

Table 1: First selection.

A second selection was made, only including studies which are related to OSA with FA and Orthodontics. Articles dealing with OSA and other diseases as OSA and weight, OSA and rapid maxillary expansion, Osa and surgical treatments, OSA and diagnosis, were excluded, so were obtained 13 specific studies on this subject but, only 8 of them were eligible by level of evidence [66]. Some review and clinical studies that dealt with OSA and other variants which were excluded from the systematic review but some helped to explain the matter. These articles were citaded in the introduction of the study. The search methodology, is illustrated in the Figure 1.

Results

Eight studies addressed to FA impact in the treatment of OSA, but the results, could not answer yet the question whether the use of the device type can improve OSA. These studies were listed below by chronological order and methodologically summarized in Table 2.

Selected Studies- Chronological order

Villa et al. [47], evaluated the clinical use and tolerance of FA for OSA treatment in 32 children at an average age of 7.1 ± 2.6 years, 20 boys and 12 girls who had OSA symptoms an AHI>1 event per hour and malocclusion. Randomly were selected 19 patients (SG) with AHI=6, which used the FA and the remaining patients formed the CG. After the treatment, the polysomnography exam showed the SG achieved a significant decrease in the AHI compared to the same index at the treatment beginning, and the CG showed no change. Clinical symptoms examination before and after the appliance use showed that 7 of the 14 subjects, had reduced 2 points in the score of respiratory symptoms, and 7 had solved the main complaints of respiratory symptoms compared to the CG which continued with baseline symptoms. Therefore, they concluded the treatment of OSA with FA is effective and well tolerated.

Cozza et al. [51], in a comparative clinical study evaluated 20 children (10 boys and 10 girls) aged between 4 and 8 years with OSA and 20 control children (10 boys and 10 girls) aged 5 and 7 years without OSA to determine the differences between groups and check the FA effects with PSG and cephalometric. Anatomic differences statistically significant were detected among CG and SG. Polysomnography was repeated after six months in the group with OSA, having noticed that the use of FA, promoted a statistically significant reduction in AHI (P=0.0003). The use of the device reduced daytime sleepiness and subjectively improved sleep quality. Parents and patients reported good cooperation in dealing with intra-oral appliance.

| Year | Author | Subject | Evidence | N | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | Carvalho et al [48] | OSA x FA | Systematic review | There are insufficient evidence in the OSA treatmentwith FA | |

| 2015 | Huynh et al.[65] | OSA x FA x ERM | Systematic review, metan | Only 6 studied for meta-analysis and no definitive results | |

| 2002 | Villa MP et al.[47] | OSA x FA X tolerance X results | Clinical Controlledrdz | 32 | FA SG had reduction of OSA and well toletou the device |

| 2011 | Godtet al.[44] | OSA x FA x cephalog x HG | Clinical observational | 209 | There was no significant change in UA in the3 SG |

| 2011 | Kizinger et al.[42] | OSA x FA x UA x Cephalom | Clinical retrospective c | 43 | Ortodontic appliances not improve OSA and cephalometric does not evaluate UA |

| 2011 | Van Holsbekeet al.[64] | OSAx FA x 3D x resistencUA | Clinical comparative | 143 | Women respond better tothe OSA treatment |

| 2004 | Cozza et al.[51] | OSA x FA x GC | Clinical comparative | 20 | dDfferences between groups were big and FA improved disease |

| 2014 | Iwasaki et al.[60] | OSA x Faxfixed x Herbst | Clinical comparative | 24 | Herbst increased UA in patients with OSA |

| Excluded | |||||

| 2006 | Rosee Schessl | OSA xFA x Frankel II | Case report | 2 | Success of FA in OSA treatment |

| 2001 | Guilleminault e Quo | OSA e FA | Literature review | Importance of dentists and orthodontists for treatment options | |

| 2013 | Chen e Lowe | OSA e FA | Literature review | Are effective but lack methods for real evidence | |

| 2012 | Pliska e Almeida | OSA x FA x treat | Literature review | FA are the first choice for mild to moderate OSA | |

| 2012 | Villa et al. | OSA x FA x surgery | Literature review | Both methods are effective but FA seems to be more efficient | |

Table 2: Evidence vased included studies (OSA e FA).

Carvalho et al. [48], through a systematic review investigated the effectiveness of treatment of OSA in children with FA. Randomized studies were selected and do not have randomized trials comparing all types of orthopedic devices with placebos or not, in children at 15 years old. They demonstrated through the results the improvement in the AHI, in the dento skeletal relations, sleep parameters, cognitive and speech, behavioral problems, quality of life, side effects, and economic and social aspects. Therefore, the authors concluded that there is no evidence enough to confirm the effectiveness of the devices for sleep disorders. The devices improve the craniofacial characteristics of children who have risk factors for OSA but there is no way to prove these.

Godt et al. [44] investigated the width of the upper airway in different facial patterns and changes during the various treatments including FA for Class II. They used cephalograms before and after the three treatment modalities (headgear, FA and bite jumping). Little increase in UA was observed around the vertical level during the treatment, and they concluded that no significant changes occurred in those segments during treatment. In addition, with headgear, the UA size decreased.

Van Holsbeke et al. [64] conducted a study with 143 patients with OSA, who used FA. CT scans were performed with minimal radiation dose before and after placement of the apparatus and the changes were verified using a bite simulator able to show resistance change in the UA. They demonstrated that ideal patients for the success were women with small UA and high early strength.

Kizinger et al. [42] in a retrospective cephalometric study found that the two forms of fixed functional appliances to correct Class II (Herbst and FA) influenced the morphology of the UA. The sample consisted of 43 patients, 18 patients used the FA and 25 used the conventional Herbst (fix FA). Measures of cephalometric analyzes were verified and compared in two times. Both devices had similar effects. They concluded that treatment with FA cannot prevent the risk of OSA although studies cephalogram are not able to measure the depth of the upper airways.

Iwasaki et al. [60], in a clinical study, observed a sample of 24 patients of Angle class II, who opted for Edwise fixed therapy compared to a group that used Herbst Fixed FA. The three dimensions of the oropharynx through CT scans, were verified in 11 children at mean age of 11.6 years old, who had already taken 3D Cone Beam before and after Herbst´s therapy. The CG was obtained in a sample of 20 patients Angle Class I, who opted for treatment with fixed orthodontic and had the same tests. The group opted for the Herbst´s appliance (SG) found a significant increase in the volume of the upper UA compared to CG.

Huynh, et al. [65] conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to check the effectiveness of orthodontic appliances in the treatment of OSA in children and adolescents. Eligible studies were investigated in Pubmed, Medline, Embase, and Internet published until April 2014 were identified, in a total of 58 studies. Only eight studies were included in the review. Among these, six were included in the meta-analysis. The search yielded only a small number of studies. Consequently, any findings of diagnostic parameters grouped and their interpretation should be treated carefully (Table 2). The researches in which patients used FA, presented clinical positive results but not statistical results. The results showed decreasing or disappearance of the OSA symptoms and also an improvement of the clinical outcome regarding craniofacial deformities caused by the sleep respiratory disorder [6,48,49,62,63,65].

Discussion

OSA has a negative impact on child growth, affecting their quality of life. If the condition persists, it may affects the quality of life in their adulthood [1,15,35-38]. Tonsil hypertrophy is considered the leading cause of OSA [1-11,13,23,27,30]and tonsillar removal is the optional treatment [3,5,6,9,10,27-29,31-34]. Common diseases such as oral breathing and primary snoring are related to OSA and if there is an association with craniofacial abnormalities, this may lead to the recurrence of the OSA after adenotonsillectomy [23,24,32-34,39,44,45,63]. The literature showed the most frequent complaints of patients with OSA were PS and troubled sleep. Allergic rhinitis RA was the most frequent comorbidity accompanying OSA, followed by hypertrophy of the tonsils [1,2,4,8,11,20,26,29]. The most severe apnea indexes were found in younger children, and African descendants had a higher prevalence of the disease [9]. One study [33] reported that the tonsillectomy surgery was effective for the treatment of OSA in a group of children aged between 3 to 6 years old, who returned to a normal growth pattern. On the other hand, other studies reported that adolescents aged between 11 and 14 years old, continued with OB after the removal of the tonsils, presented the worst AHI and reduction of UA lumen [5,6,9,10,29,34]. The causal effect between tonsil hypertrophy and OSA has not been established yet [40,45].

Treatments for persistent apnea are not completely known yet. Treatment approaches must be better evaluated [10,11]. Anti-inflammatory therapies, masks for ventilation and oral appliances are offered to the treatment of recurrent OSA but the disease remains a challenge due to its multifactorial nature [1-3,11,39,48,63,65]. Some authors consider as the best form of clinical treatment of OSA the use of CPAP or BPAP but such treatment does not get a good patients cooperation and the discontinuance is large [26,27,39,40,41].

Two reports of clinical case studies demonstrated OSA improvement with the use of FA [49,50]. In both studies, high AHI were reported, but the patients did not have tonsillar hypertrophy and craniofacial deformities were treated with FA. The treatment improved the OSA and normalized the craniofacial deformities. Reports of clinical cases do not represent a high level of evidence and do not show statistical significance, but can be considered a warning about the clinical need of new approaches. Isolated cases, out of average, should be considered for further investigation. Early intervention of the orthodontist with FA in patients with disorders of the craniofacial structures in cooperation with other specialists should be considered [26,27]. The FA promotes an increase in mandibular growth and permanently changes in the craniofacial structure, facilitating the breathing mode and preventing obstructions of the UA. [42]Orthodontists are professionals trained to recognize and treat OSA with FA in patients with craniofacial anomalies [5,6,15,25,28] promoting a harmonious facial growth and avoid aggressive surgery in adulthood and cardiovascular comorbidities resulting from sleep disorders [16,41,42,62].

The FA are simple, silent, well tolerated and effective, but some challenges still remain, as the need for monthly monitoring by the professional for more than twelve months, which may discourage the patient[43-66]. Studies have shown that the use of FA can eliminate or reduce the symptoms of the OSA, promoting a better long-term quality of life [35-38]. The PSG tests have been considered the gold standard in OSA diagnosis. Perhaps due to the difficulty in performing these exams, by of the lack of specialized centers and the high cost, making most of the clinical researches outcomes were not investigated with this exam. Some of the studies were not able to include enough patients for an statistical result maybe because of the difficulty of suitable sample allocation in the inclusion criteria [5,6,14,42-50,52,59-65].

Some researchers used 2D image parameters to check UA [42,44,51] and did not obtain reliable results. Few studies included patients monitored with polysomnography [42,44,47] and were not able to report improvement of OSA based on AHI parameters.

The difficulty in assessing the results of the studies was due to the differences in the used methodologies. The different investigated devices and patient maturity were not homogeneous, creating difficulties in the methodological comparisons. Many of them, showed positive results in the improve of OSA with FA but the parameters used to measure the effectiveness were not similar and acceptable [42,44,47,51,60,64]. A recent study of systematic review [65] evaluated several types of orthodontic therapy, and did not answer the purpose of our research. Due to the difficulty of conducting well-designed studies with samples and suitable tests for good results, there is no strong evidence that FA is indeed effective in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in children.

Conclusion

This systematic literature review showed that orthopedic devices seem to be a good treatment option for children with OSA. Although the level of evidence of the effectiveness of these devices is weak to moderate, as there are no randomized controlled clinical studies that support this hypothesis (H0), but either do not reject it. There is still need for more well designed controlled research, with large enough case series in order to accurately obtain the answer.

References

- Pignatari SSN, Pereira FC, Avelino MAG, Fujita RR (2002) Noções gerais sobre a sÃndrome da apnéia e da hipopnéia obstrutiva do sono em crianças e o papel da polissonografia.Tratado de Otorrinolaringologia. (1stedn), São Paulo, Brazil, South America.

- Ramos RTT, Daltro, CHDC, Gregório (2006) em crianças: perfil clÃnico e respiratório polissonográfico. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol 72.

- Rosen CL (2004) Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children: controversies in diagnosis and treatment. Pediatr Clin North Am 51: 153-167, vii.

- Powell S, Kubba H, O'Brien C, Tremlett M (2010) Paediatric obstructive sleep apnoea. BMJ 340: c1918.

- Guilleminault C, Stoohs R (1990) Chronic snoring and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children. Lung 168 Suppl: 912-919.

- Guilleminault C, Quo SD (2001) Sleep-disordered breathing. A view at the beginning of the new Millennium. Dent Clin North Am 45: 643-656.

- Marcus CL (2001) Sleep-disordered breathing in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164: 16-30.

- Gregório PB, Athanazio RA, Bitencourt AG, Neves FB, Terse R, et al. (2008) [Symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome in children]. J Bras Pneumol 34: 356-361.

- American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). (2002) Subcommittee on Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. Clinical practice guideline: diagnosis and management of childhood obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Pediatrics 109: 704-712.

- Nixon GM, Brouillette RT (2005) Sleep . 8: paediatric obstructive sleep apnoea. Thorax 60: 511-516.

- Gozal D, Kheirandish-Gozal L (2006) Sleep apnea in children--treatment considerations. J Orofac Orthop. 67:58-67

- Wise MS, Nichols CD, Grigg-Damberger MM, Marcus CL, Witmans MB, et al. (2011) Executive summary of respiratory indications for polysomnography in children: an evidence-based review. Sleep 34: 389-398AW.

- Avelino MA, Pereira FC, Carlini D, Moreira GA, Fujita R, et al. (2002) Avaliação polissonográfica da sÃndrome da apnéia obstrutiva do sono em crianças, antes e após adenoamigdatomia. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol 68: 308-311.

- Iwasaki T, Saitoh I, Takemoto Y, Inada E, Kanomi R, et al. (2011) Evaluation of upper airway obstruction in Class II children with fluid-mechanical simulation. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 139: e135-145.

- Weber SA, Montovani JC, Matsubara B, Fioretto JR (2007) Echocardiographic abnormalities in children with obstructive breathing disorders during sleep. J Pediatr (Rio J) 83: 518-522.

- Mello Junior CF, Guimarães Filho HA, de Brito Gomes CA, de Amorim Paiva CC (2013) Achados radiológicos em pacientes portadores de apneia obstrutiva do sono. Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia 39(1).

- Vos W, De Backer J, Devolder A, Vanderveken O, Verhulst S, et al. (2007) Correlation between severity of sleep apnea and upper airway morphology based on advanced anatomical and functional imaging. J Biomech 40: 2207-2213.

- Aboudara C, Nielsen IB, Huang J C, Maki K, Miller AJ, et al. (2009) Comparison of airway space with conventional lateral headfilms and 3-dimensional reconstruction from cone-beam computed tomography. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 135: 468-479.

- Moraes de MEL, Hollender LG, Chen (2011) Evaluating craniofacial asymmetry with digital cephalometric images and cone-beam computed tomography. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 139: 523-531.

- Schendel SA, Hatcher D (2010) Automated 3-dimensional airway analysis from cone-beam computed tomography data. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 68: 696-701.

- Zinsly SDR, Moraes LCD, Moura PD, Ursi W (2015) Assessment of pharyngeal airway space using Cone-Beam Computed Tomography. Dental Press Journal of Orthodontics 15: 150-158.

- El H, Palomo JM (2010) Measuring the airway in 3 dimensions: a reliability and accuracy study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 137: S50.

- Abramson Z, Susarla S, August M, Troulis M, Kaban L (2010) Three-dimensional computed tomographic analysis of airway anatomy in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Oral 68: 354-362.

- Kapila S, Conley RS, Harrell Jr WE (2011) The current status of cone beam computed tomography imaging in orthodontics. DentomaxillofaciaRadiology 40: 24-34.

- Ianni DF, Bertolini MM, Lopes ML (2006) Contribuição multidisciplinar no diagnóstico e no tratamento das obstruções da nasofaringe e da respiração bucal R Clin Ortodon Dental Press 4: 90-102.

- Capua M, Ahmadi N, Shapiro C (2009) Overview of obstructive sleep apnea in children: exploring the role of dentists in diagnosis and treatment. J Can Dent Assoc 75: 285-289.

- Tapia IE, Marcus CL (2013) Newer treatment modalities for pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Paediatr Respir Rev 14: 199-203.

- Mora R, Salami A, Passali FM, Mora F, Cordone MP, et al. (2003) OSAS in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 67 Suppl 1: S229-231.

- Ferguson KA, Cartwright R, Rogers R, Schmidt-Nowara W (2006) Oral appliances for snoring and obstructive sleep apnea: a review. Sleep 29: 244-262.

- Vieira FMJ, Diniz F (2003) Hemorragia na adenoidectomia e/ou amigdalectomia: estudo de 359 casos. Rev bras Otorrinolaringol 69: 338-341

- Samuel C Leong Sujata De (2010) Changing trends of adeno-tonsillectomy for paediatric obstructive sleep apnoea. BMJ.

- Morton S, Rosen C, Larkin E, Tishler P, Aylor J, et al. (2001) Predictors of sleep-disordered breathing in children with a history of tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy. Sleep 24: 823-829.

- Â Mattar SE, Valera FC, Faria G, Matsumoto MA, Anselmo-Lima WT (2011) Changes in facial morphology after adenotonsillectomy in mouth-breathing children. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 21: 389-396

- Shott SR (2011) Evaluation and management of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea beyond tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 19: 449-454.

- Goldstein NA, Fatima M, Campbell TF, Rosenfeld RM (2002) Child behavior and quality of life before and after tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 128: 770-775.

- Eckenhoff JE (1953) Relationship of anesthesia to postoperative personality changes in children. AMA Am J Dis Child 86: 587-591.

- Silva VC, Leite AJ (2006) Quality of life in children with sleep-disordered breathing: evaluation by OSA-18. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 72: 747-756.

- Gomes Ade M, Santos OM, Pimentel K, Marambaia PP, Gomes LM, et al. (2012) Quality of life in children with sleep-disordered breathing. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 78: 12-21.

- Marcus CL, Rosen G, Ward SL, Halbower AC, Sterni L, et al. (2006) Adherence to and effectiveness of positive airway pressure therapy in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Pediatrics 117: e442-451.

- Balbani AP, Weber SA, Montovani JC (2005) Update in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 71: 74-80.

- Cheng MC, Enlow DH, Papsidero M, Broadbent BH Jr, Oyen O, et al. (1988) Developmental effects of impaired breathing in the face of the growing child. Angle Orthod 58: 309-320.

- Kinzinger G, Czapka K, Ludwig B, Glasl B, Gross U, et al. (2011) Effects of fixed appliances in correcting Angle Class II on the depth of the posterior airway space: FMA vs. Herbst appliance: a retrospective cephalometric study. J Orofac Orthop.72: 301-320.

- Guilleminault C, Huang YS, Quo S, Monteyrol PJ, Lin CH (2013) Teenage sleep-disordered breathing: recurrence of syndrome. Sleep Med 14: 37-44.

- Godt A, Koos B, Hagen H, Göz G (2011) Changes in upper airway width associated with Class II treatments (headgear vs activator) and different growth patterns. Angle Orthod 81: 440-446.

- Rossi RC, Rossi NJ, Rossi NJ, Yamashita HK, Pignatari SS (2015) Dentofacial characteristics of oral breathers in different ages: a retrospective case-control study. Prog Orthod 16: 23.

- Schütz TC, Dominguez GC, Hallinan MP, Cunha TC, Tufik S (2011) Class II correction improves nocturnal breathing in adolescents. Angle Orthod 81: 222-228.

- Villa MP, Bernkopf E, Pagani J, Broia V, Montesano M, et al. (2002) Randomized controlled study of an oral jaw-positioning appliance for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in children with malocclusion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165: 123-127.

- Carvalho FR, Lentini-Oliveira D, Machado MA, Prado GF, Prado LB, et al. (2007) Oral appliances and functional orthopaedic appliances for obstructive sleep apnoea in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev : CD005520.

- Rose E, Schessl J (2007) Orthodontic procedures in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in children. Paediatr Respir Rev 7: S58-61.

- Horihata A, Ueda H, Koh M, Watanabe G, Tanne K (2013) Enhanced increase in pharyngeal airway size in Japanese class II children following a 1-year treatment with an activator appliance. Int J Orthod Milwaukee 24: 35-40.

- Cozza P, Polimeni A, Ballanti F (2004) A modified monobloc for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea in paediatric patients. Eur J Orthod 26: 523-530.

- Cozza P, Baccetti T, Franchi L, De Toffol L, McNamara JA Jr (2006) Mandibular changes produced by functional appliances in Class II malocclusion: a systematic review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 129: 599.

- Baccetti T, Franchi L (2001) The Fourth Dimension in Dentofacial Orthopedics: Treatment Timing for Class II and Class III Malocclusions. World Journal of Orthodontics 2: 159-167

- Rossi RC, Rossi NJ, Rossi NCJ, Pignatari SSN (2015) Effects of the Rossi activator over Class II treatment of pre-adolescent patients – randomized controlled trial Ortho Scienc 30: 173-179.

- Rossi NJ (1993) The Rossi orthopedic appliance: model preparation and appliance construction. Funct Orthod 10: 22-24, 26-9.

- Rossi NJ, Rossi RC (1996) Indication of the Rossi orthopedic appliance: a case study. Funct Orthod 13: 36-40.

- Rossi NJ, Rossi RC (1988) Ortopedia funcional integrada à ortodontia corretiva. São Paulo:Editora Pancast.

- Fox NA (2007) Insufficient evidence to confirm effectiveness of oral appliances in treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome in children. Evid Based Dent 8: 84.

- Ghodke S, Utreja AK, Singh SP, Jena AK (2014) Effects of twin-block appliance on the anatomy of pharyngeal airway passage (PAP) in class II malocclusion subjects. Prog Orthod 15: 68.

- Iwasaki T, Takemoto Y, Inada E, Sato H, Saitoh I, et al. (2014) Three-dimensional cone-beam computed tomography analysis of enlargement of the pharyngeal airway by the Herbst appliance. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 146: 776-785.

- Hänggi MP, Teuscher UM, Roos M, Peltomäki TA (2008) Long-term changes in pharyngeal airway dimensions following activator-headgear and fixed appliance treatment. Eur J Orthod 30: 598-605.

- Pliska BT, Almeida F (2012) Effectiveness and outcome of oral appliance therapy. Dent Clin North Am 56: 433-444.

- Villa MP, Milano S, Rizzoli A (2012) Mandibular advancement devices are an alternative and valid treatment for pediatric obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep Breath. 16: 971-976.

- Van Holsbeke C, De Backer J, Vos W, Verdonck P, Van Ransbeeck P, et al. (2011) Anatomical and functional changes in the upper airways of sleep apnea patients due to mandibular repositioning: a large scale study. J Biomech 44: 442-449.

- Huynh NT, Desplats E, Almeida FR (2015) Orthodontics treatments for managing obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev.

- Sackett DL (2000) Evidence-based medicine. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., USA.

Citation: Rossi RC, Rossi NJ, Rossi NC, Fujiya RR, Pignatari SN (2015) Functional Appliances in the Treatment of Sleep Apnea in Children: A Systematic Review. Otolaryngol (Sunnyvale) 5:212. DOI: 10.4172/2161-119X.1000212

Copyright: © 2015 Rossi RC et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 15182

- [From(publication date): 11-2015 - Nov 21, 2024]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 10605

- PDF downloads: 4577