Fatal Alcohol Poisonings and Poisonings by Other Toxic Substances in Russia

Received: 14-Aug-2017 / Accepted Date: 25-Sep-2017 / Published Date: 02-Oct-2017 DOI: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000344

Abstract

Background: It is widely believed that one of the negative consequences of Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign in Russia in the mid-1980s was the dramatic growth in the number of deaths from poisonings by non-beverage alcohol surrogates. Objective: This paper aims to clarify this important issue by analyzing the trends in fatal alcohol poisonings and poisonings by other toxic substances in Russia between 1956 and 2005. Methods: To examine the relation between fatal alcohol poisonings and poisonings by other toxic substances trends across the study period a time series analysis was performed using the statistical package “Statistica 12. StatSoft”. Results: The alcohol poisonings mortality rates for both sexes dropped sharply between 1984 and 1988. Substantial reduction was also recorded in the number of deaths from poisonings by other toxic substances in the mid-1980s. According to the results of time-series analysis there was a positive and statistically significant association between fatal poisonings by alcohol and poisonings by other toxic substances at the population level. Conclusion: The official statistical data do not support the claims that the Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign contributed to the dramatic growth in fatal poisonings by non-beverage alcohol surrogates.

Keywords: Fatal alcohol poisonings; Poisonings by other toxic substances; Mortality

Introduction

Alcohol is the biggest killer in Russia, accounting for about half of deaths among working-age men [1-3]. The rate of deaths from alcohol poisoning in this country is among the highest in the world [4]. Compelling evidence suggests that the alcohol surrogates (industrial spirits, antiseptics, lighter fluid and medications containing alcohol) may be responsible for the extremely high level of fatal alcohol poisonings in Russia [5]. Some experts reasonably argue that alcohol surrogates pose a risk to human health and undermine alcohol control policy measures introduced in this country over the last decade [6,7].

Historically, alcohol control policies designed to restrict availability of legal alcohol in Russia have driven surrogates consumption growth. Alcohol surrogates consumption increased substantially following the prohibition of vodka sales in Russia during World War I [8]. A similar rapid rise in consumption of moonshine (Samogon) and surrogates has occurred during Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign in the mid-1980s [9]. This campaign is the most well-known natural experiment in the field of alcohol policy. In May 1985 Gorbachev launched the anti-alcohol campaign which was design to tackle alcohol-related problems in the Soviet Union by restricting the availability and affordability of alcohol [1].

The opinions about the effects of this natural experiment vary substantially. Most experts agree that the campaign did produce a number of positive effects, such as a decline in alcohol consumption and a drop in alcohol-related mortality [1,4]. Furthermore, the antialcohol campaign has shown that alcohol control measures may have a direct impact on population drinking and alcohol-related harm in Russia. Some experts, however, argue that the beneficial health and social effects of this campaign have been overestimated [10]. It is widely believed that one of the negative consequences of this campaign was the dramatic growth in the number of deaths from poisonings by non-beverage alcohol surrogates [11].

This paper aims to clarify this important issue by analyzing the trends in fatal alcohol poisonings and poisonings by other toxic substances in Russia between 1956 and 2005.

Materials and Method

The data on age-adjusted sex-specific mortality rates per 1000.000 of the population are taken from the Russian State Statistical Committee (http://www.gks.ru). To examine the relation between fatal alcohol poisonings and poisonings by other toxic substances trends across the study period a time series analysis was performed using the statistical package “Statistica 12. StatSoft.” Bivariate correlations between the raw data from two time series can often be spurious due to common sources in the trends and due to autocorrelation [12]. One way to reduce the risk of obtaining a spurious relation between two variables that have common trends is to remove these trends by means of a “differencing” procedure. The process whereby systematic variation within a time series is eliminated before the examination of potential causal relationships is referred to as “prewhitening.” This is subsequently followed by an inspection of the cross-correlation function in order to estimate the association between the two prewhitened time series.

Results and Discussion

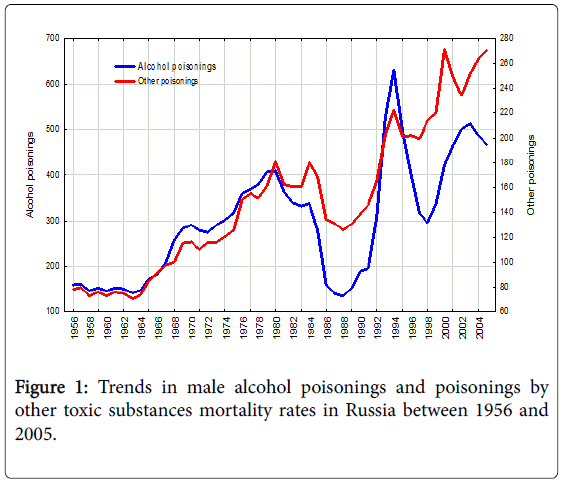

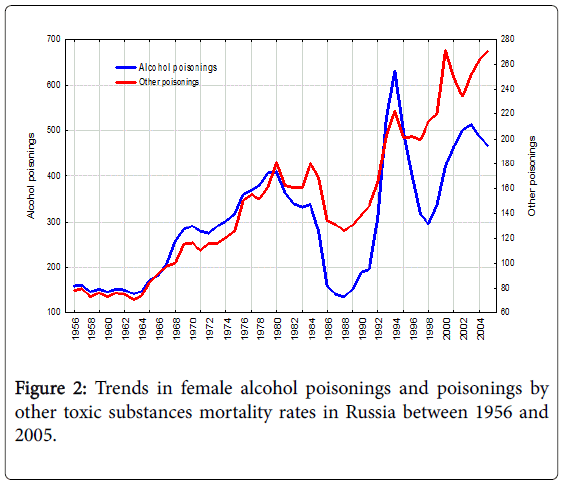

According to official statistics, the male alcohol poisonings mortality rate increased 2.9 times (from 159.7 to 469.7 per 1000.000 populations), while the number of deaths from poisonings by other toxic substances increased 3.5 times (from 78.4 to 270.4 per 1.000.000 population) in Russia from 1956 to 2005. The female alcohol poisonings mortality rate increased 4.1 times (from 27.9 to 113.6 per 1000.000 populations), while the number of deaths from poisonings by other toxic substances increased 1.6 times (from 37.0 to 60.2 per 1.000.000 populations) during the same period. Across the whole period the male alcohol poisonings mortality rate was 2 times higher than the mortality rate from poisonings by other toxic substances (298.7 vs. 149.5 per 1000.000 populations) with a rate ratio of 2.0 in 1956 decreasing to 1.73 by the 2005. The female alcohol poisonings mortality rate was 1.5 times higher than the mortality rate from poisonings by other toxic substances (66.2 vs. 44.8 per 1000.000 populations) with a rate ratio of 0.75 in 1956 increasing to 1.9 by the 2005.

The trends in the sex-specific fatal alcohol poisonings and poisonings by other toxic substances are displayed in Figures 1 and 2. The graphical evidence suggests that both trends closely follow each other across the study period. A Spearman correlation analysis suggests a strong association between two variables for males (r=0.85; p<0.000) and females (r=0.94; p<0.000). There were sharp trends in the time series data across the entire study period. These systematic variations were well accounted for by the application of first-order differencing. After pre-whitening the cross-correlations between fatal poisonings by alcohol and poisonings by other toxic substances time series were inspected. The outcome indicated statistically significant cross-correlation between the two variables for males (r=0.67; Standard error=0.13) and females (r=0.73; Standard error=0.13) at lag zero. According to the results of time-series analysis there was a positive and statistically significant association between fatal poisonings by alcohol and poisonings by other toxic substances at the population level. This research evidence suggests that these phenomena are closely interrelated.

As can be seen from Figures 1 and 2, the alcohol poisonings mortality rates for both sexes dropped sharply between 1984 between 1988. Substantial reduction was also recorded in the number of deaths from poisonings by other toxic substances in the mid-1980s. Thus, the empirical evidence does not support the claims that the anti-alcohol campaign contributed to the dramatic growth in fatal poisonings by non-beverage alcohol surrogates.

A large increase in the drinking of poor quality illegal alcohol and non-beverage alcohol surrogates underlies the extremely high rates of fatal poisonings by alcohol and poisonings by other toxic substances recorded in the early 1990s [1]. Several cases of mass poisoning by alcohol surrogates were recorded during the last decade [13]. The case of surrogate poisoning was registered in Yekaterinburg (Siberia) in 2004, and further reports spread among the Russian regions during the following years [5]. Consumption of surrogate alcohols which contains high concentrations of methanol remains a widespread problem in contemporary Russia [7].

Conclusion

In conclusion, the official statistical data do not support the claims that the Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign contributed to the dramatic growth in fatal poisonings by non-beverage alcohol surrogates. The parallel trends in mortality from alcohol poisonings and poisonings by other toxic substances may suggest that a substantial number of deaths from other toxic substances are actually deaths from alcohol surrogates. In relation to this, the Russian government should consider a number of potentially effective approaches addressing to the problem of the non-beverage alcohol surrogates, including raising public awareness of the life treating danger, posed by these products.

References

- Nemtsov AV, Razvodovsky YE (2008) Alcohol situation in Russia, 1980-2005. J Soc Clin Psychol 2: 52-60.

- Nemtsov AV, Razvodovsky YE (2017) The estimation of the level of alcohol consumption in Russia: A review of the literature. Sobriology 1: 78-88.

- Razvodovsky YE, Nemtsov AV (2016) Alcohol-related component of the mortality decline in Russia after 2003. The Questions of Narcology 3: 63-70.

- Stickley A, Leinsalu M, Andreev E, Razvodovsky Y, Vågerö D, et al. (2007) Alcohol poisoning in Russia and the countries in the European part of the former Soviet Union, 1970 2002. Eur J Public Health 17: 444-449.

- Razvodovsky YE (2008) Noncommercial alcohol in central and eastern Europe, ICAP Review 3. In: International Center for Alcohol Policies, ed. Noncommercial alcohol in three regions. Washington, DC: ICAP 17-23.

- Solodun YV, Monakhova YB, Kuballa T, Samokhvalov AV, Rehm J, et al. (2011) Unrecorded alcohol consumption in Russia: Toxic denaturants and disinfectants pose additional risks. Interdiscip Toxicol 4: 198-205.

- Neufeld M, Lahenmeier D, Hausler T, Rehm J (2016) Surrogate alcohol containing methanol, social deprivation and public health in Novosibirsk, Russia. Int J Drug Policy 37: 107-110.

- Stickley A, Razvodovsky Y, McKee M (2009) Alcohol mortality in Russia: A historical perspective. Public Health 123: 20-26.

- Segal B (1990) The drunken society-Alcohol abuse and alcoholism in the Soviet Union. Hippocrene Books, New York.

- Tarschys D (1993) The Success of a Failure: Gorbachev's Alcohol Policy, 1985-1988. Europe-Asia Studies 45: 7-25.

- Jargin SV (2015) Alcohol abuse in Russia: History and perspectives. J Addict Behav Ther Rehab 491: 2-6.

- Box GEP, Jenkins GM (1976) Time series analysis: Forecasting and control. London. Holden-Day Inc.

- Nemtsov AV, Razvodovsky YE (2016) Russian alcohol policy in false mirror. Alcohol Alcohol 4: 21.

Citation: Razvodovsky YE (2017) Fatal Alcohol Poisonings and Poisonings by Other Toxic Substances in Russia. J Addict Res Ther 8: 344. DOI: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000344

Copyright: © 2017 Razvodovsky YE. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 4357

- [From(publication date): 0-2017 - Apr 11, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 3543

- PDF downloads: 814