Review Article Open Access

Factors Related to Spirituality for Terminally ill Cancer Patients through Life Review Interview in Japan

Michiyo Ando1* and B Tatsuya Morita21Faculty of Nursing, St Mary’s College, Tsubukuhonmachi 422, Kurume City, Fukuoka, Japan

2Department of Palliative and Supportive Care, Palliative Care Team and Seirei Hospice, Seirei Mikatahara Hospital, Shizuoka, Japan

- *Corresponding Author:

- Michiyo Ando

Faculty of Nursing, St. Mary’s College

Kurume City, Fukuoka, Japan

Tel: +81-942-50-0744

E-mail: andou@st-mary.ac.jp

Received date:May 11, 2012; Accepted date: June 16, 2012; Published date: June 18, 2012

Citation: Ando M, Morita BT (2012) Factors Related to Spirituality for Terminally ill Cancer Patients through Life Review Interview in Japan. J Palliative Care Med S1:002. doi: 10.4172/2165-7386.S1-002

Copyright: © 2012 Ando M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine

Abstract

Terminally ill cancer patients feel spiritual pain such as loss of meaning to live or existence, and one of the psychological cares is life review interview. Life review seems to be useful to integrate patients’ lives and we conducted a series of life review studies. The present study proposes factors related with spirituality through our previous life review studies. Firstly we conducted both the Structured Life Review in which there were about 4 session times for a terminally ill cancer patient individually and identified some factors which improved patients’ spirituality by a text mining of PC software. Secondary, we conducted the Short-Term Life Review in which there were 2 session times for them to complete this therapy, and patients’ narrative were analyzed by the same way. By considering positive effective factors with non-positive effective factors, we observed the following four dimensions. Good human relationships vs. Bad human relationships; 2) Good memories and life satisfaction vs. Bad memories and poor life satisfaction (including attainments or self-confidence); 3) Pleasure in the past and Daily Activities vs. Confrontation of practical problems (including worries about future); and 4) Integrative life review style vs. Non-integrative life review style. These dimensions appear to be more predictive factors about the efficacy of spiritual wellbeing in terminal cancer patients, particularly after life review is conducted.

Keywords

Life review; Spirituality; Effective-factors

Introduction

Spirituality is both universal and inclusive, and it revolves around the meaning of life and faith rather than religion. In addition, although it involves a relationship with the self and to others, it may or may not involve relationships with a so-called “higher being” [1]. In Japan, cancer is one of main causes of death and Ministry of Health Labor and Welfare tried to cope with this fact, in which development of an intervention for improving patients’ quality of life was recognized as an important plan. Based on this background, Murata and Morita [2] defined spiritual wellbeing as the state where a patient’s overall sense of meaning in life and mind is at peace from a survey of nationwide study. This definition was applied to the present study. Terminally ill cancer patients sometimes lose the meaning of life or purpose, and as a result, they do not have peace of mind. The importance of the meaning of life is shown by its association with spiritual wellbeing [3] or the correlation between the satisfaction of spiritual support and the quality of life for cancer patients [4]. These studies suggest the need for more attention to spiritual wellbeing for terminally ill cancer patients. Therefore, life review is one of the most effective therapies.

Butler [5] reported that the life-review process is a means of reintegration, which can lend new significance and meaning to an individual’s life. A life-review interview (hereafter, life review) is a type of reminiscence therapy [5] that includes various activities such as reminiscence, evaluation, and the reconstruction of one’s entire life [6]. The popular life-review method, the structured life review [6] consists of about from 4 to 6, one-hour visits with each client.

In regard to the elderly, the positive effects of life reviews were shown to alleviate symptoms of depression [7,8] and raise overall selfesteem [9,10].

To date, there have been very few studies on the use of lifereview methods for terminal cancer patients. Therefore, the present study examines the life review process, and the factors related to the culminating effects of this type of therapy.

Factors Related to Spirituality in Each Life Review Interview Study

Ando, et al. (2007) [11] evaluated the treatment efficacy of life reviews on the spiritual wellbeing of terminal cancer patients, and explored the differences in the responses of the patients who either gained clinical benefits or did not. The subjects consisted of patients with incurable cancer receiving specialized care in the palliative-care unit of a general hospital in Japan. The inclusion criteria for this study were based on four overall factors: 1) the patient had incurable cancer; 2) the patient had no cognitive impairment; 3) the patient was 20 years of age or older; and 4) the primary physicians were in agreement that the patient would in fact benefit from the psychological interventions. The interviewer was a clinical psychologist who conducted a constructive life review [6] in which patients reviewed their own childhood, adolescence, adult life, and current situation. The interviews included: 1) Please tell me about your childhood; 2) What are the most memorable events from your childhood?, and 3) How do you feel now when you think about those events? Four sessions were planned for each patient and the interviews were conducted in either the dayroom or at the bedside. The responses from the interview were recorded in the form of notes taken during or immediately after the session.

To evaluate the level of spiritual wellbeing, we used the SELT-M [12]. To explore the factors related with efficacy on spirituality, we classified the patients into two overall groups: Effective (patients who showed an increase in their overall Quality of Life (QOL) score on the SELT-M following the intervention) and Little-Effective (the remaining patients). We then examined the responses given during the life-review sessions for the two groups by using Word Miner version 1.0 (a textmining computer software program) [13]. Text mining in general is used to extract specific and pertinent information from a large amount of textual data.

Three factors were extracted by correspondence analysis, in which words were extracted by frequencies from positive to negative direction like dimensions in a graph, and named the factor (Table 1). First, the “Positive View of Life” factor included statements such as “putting affairs in order” or “I find beauty in the outdoors” for the positive direction or “I can walk by myself” or “pleasantness” for the minus direction. Second, the “Pleasure in Daily Activities and Good Human Relationships” factor included “pets” or “likes” for the positive direction, whereas “I have good human relationships” or “relatives” were offered for the minus direction. The third and final factor, “Balanced Evaluation of Life” included statements such as “I had a good time” or “destiny” for the positive direction, and “contact” or “old friend” for the minus direction.

| Effective factors | Little Effective factors | |

|---|---|---|

| Ando et al. (2007) [11] | ・Good human relationships ・Positive view of life ・Pleasure in daily activities ・Balanced evaluation of life |

・Worries about future caused by disease ・Conflicts in family relationship problems ・Confrontation of practical problems |

| Ando et al. (2010) [15] | ・Good memories of family ・Feelings of attainment ・Integrative life review |

・Bitter memories ・Non-integrative life review |

| Ando et al. (2012) [20] | ・Good family relationships ・Self confidence in working hard ・Being watched by God |

・Regret regarding children’s education ・Poor human relationships |

Table 1: The effective and little-effective factors on spiritual well-being through life review.

In regard to the Little-Effective group, three factors were also extracted by correspondence analysis. First, the “Worries about the Future Caused by Disease” factor included comments such as “I am unsatisfied with life” or “I want to leave something” for the positive direction and “children” or “everyone crosses the road to death” for the minus direction. The second factor, “Conflicts in Family Relationship Problems,” included statements of “problems with mother” or “past conflicts” for the positive direction and “parents” or “I have relied on my family” for the minus direction. The third and final factor “Confrontation Practical Problems” included the comments “I am at a loss” or “troubles” for the positive direction, and “bad physical condition” or “I don’t want to give anyone trouble” for the minus direction.

In the above study [11] for the structured life review, approximately 30% of the patients failed to complete all of the sessions. Therefore, Ando, et al. (2008) [14] developed a new type of life review called the “Short-Term Life Review,”(STLR) which required only two sessions that focused on terminal cancer patients. In the first session, the patients reviewed their overall lives and their responses were recorded and edited. The psychologist then created a simple album of words and pictures based on the patient’s narrative. In the second session, the patient and the psychologist reviewed the album together for validation. Ando, et al. (2010) [15] focused only on the patients who were confined to bed due to the limited amount of time. In addition, they clarified the efficacy of spiritual wellbeing for the patients with the lowest Performance Status (PS4). The participants included 13 terminal cancer patients. Their performance status was measured on the ECOG PSR scale [16] that consists of a single-item rating of five activity levels: 0= fully active; 1= prohibited from physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to do light work of a sedentary nature; 2= ambulatory and able to care for oneself but unable to work for more than half of the waking hours; 3= capable of only limited self-care and confined to either a bed or a chair for more than half of the waking hours; 4= completely disabled, unable to care for oneself, and confined to either a bed or a chair.

The main questions focused on six aspects: 1) the most important events in their life; 2) the most impressive memories; 3) the most influential persons and/or events; 4) their most important roles in life; 5) the proudest moment of their life; and 6) what they wanted to pass on to the important people in their life or the younger generation. The procedure for the STLR has been described in our earlier study. Patients completed the Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Wellbeing (FACIT-Sp) [17,18] pre and post intervention. Based on the fragments found in the correspondence analysis by text mining of PC soft like a previous study, the most important fragments were tabulated after performance of the significance test. Narratives were separated into the Effective group and the Little-Effective group by differences of FACITSp score pre and post STLR.

From the Effective group, fragments such as “I have good memories of my family” “My family is most important in my life,” or “I have made my garden” were ranked high. From these fragments, we identified “Good memories of family” and “Feelings of attainment” as factors with a positive influence on spiritual wellbeing. In addition, several fragments for this group of patients involved emotion or evaluation with examples such as “I worked sincerely” or “I am satisfied with my work.” A life review accompanied with either an acceptance of the past as worthwhile or acceptance of negative life events is called an “Integrative life review” . Therefore, we designated this factor under the same name.

From the Little-Effective group, fragments such as “we were isolated for 45 days” or “I was disinfected after the war” also ranked high. From these fragments, we identified “Bitter memories” as a factor with low spiritual wellbeing. Moreover, fragments like “A historical person influenced me,” or “my role was to prevent accidents (in the company)” ranked high. From these fragments, we identified the factor “Non-integrative life review” that represents the patients who excluded emotion or evaluation in the review with an overall tendency to review in a factual manner only. In other words, they did not accept their past or refused to reconcile any unresolved problems.

In Ando et al. [14], since the number of participants were minimal (n= 18), Ando, Morita, and Akechi (2010) [19] confirmed the results in a randomized controlled study. The participants consisted of cancer patients from the Palliative Care Units (PCUs) of two general hospitals in western Japan. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were the same as the previous study. Following the STLR, the patients completed the FACIT-Sp scores. Of the 34 patients, 20 completely answered the question items. Responses to the questions in the STLR, which is an intervention group, were examined by using correspondence analysis with the Word Miner program [20]. The following included the question items and high-ranking fragments that were reduced as factors: High-ranked fragments that were associated with a high FACITSp score included “daughter,” “working hard,” and “God”. From these fragments, we identified “Good family relationships,” “Self-confidence in working hard,” and “Being watched by God” as important factors. Conversely, fragments associated with a low FACIT-Sp score included “children’s education,” “grandchildren,” and “teaching”. From these fragments, we identified “Regret regarding children’s education” and “Poor human relationships” as important factors.

Factors Related to Spiritual Wellbeing Through our Life Review Interviews

We have examined the studies regarding life reviews for terminal cancer patients. Though the life review method is different between the structure life review and the Short-Term Life Review (STLR), commonality is observed (Table 1).

To conduct an effective life review, we must first realize that “Good human relationships” or “Good family relationships” are similar, which is also associated with “Good memories of family.” Patients who mentioned “Good memories of family” had good human relationships with their families, which were indispensable for overall peace of mind among people in Japan [21]. Moreover, this importance of human relationships is supported by the findings of Miyashita, et al. (2007) [22] and Murata and Morita [2].

At a secondary level, the “Feelings of attainment” and “Self confidence in working hard” are also similar factors. When patients look back at their lives, they may also be satisfied with their lives in general. In addition, many patients felt that “Raising and educating children” were attainments rather than successes in their business or company. Since patients in Japan might have some difficulty answering the question on pride due to the unacceptability of self-praise [23], their point of view is more related to self-confidence.

Finally, “Balanced evaluation of life” and “Integrative life review” are also similar factors. “Balanced evaluation of life” is considered an important factor when life reviews function as therapeutic tools. Haight (1998) [6] stated that negative memories are more important than positive ones when achieving integration for a successful life review. That is, integrating both good and bad memories is effective. In regard to “integrative life review,” patients expressed a general feeling of peacefulness after they rearranged their lives in a more meaningful way [24].

Moreover, “Positive view of life,” “Pleasure in daily activities,” and “Being watched by God” was a general characteristic. “Positive view of life” and “pleasure in daily activities” may be an important factor in cognitive behavior therapy. Greer and Moorey [25] showed the importance of leisure by demonstrating how patients generally enhanced their daily life with activities that were not impeded by the afflicting disease.

In contrast, “Conflicts in family relationship problems” and “Poor human relationships” were common in the Lon-Effective group. In other words, poor human relationships might result in loneliness. At a secondary level, “Bitter memories” and “Regret regarding children’s education” were similar factors. For those patients who had bitter memories (such as World War II) and reviewed only facts without accepting the positive or negative aspects of their past, life review might not be effective. Moreover, “Worries about my future caused by disease,” “confrontation of practical problems,” and “Non-integrative life review” are characteristics of this group. When patients worry about future, or have practical problems such as burial arrangements or economical problems, life review is not so effective. In addition, since they conduct a “Non-integrative life review” by excluding emotion or evaluation, and do not attempt to accept their past, this therapy is not much effective.

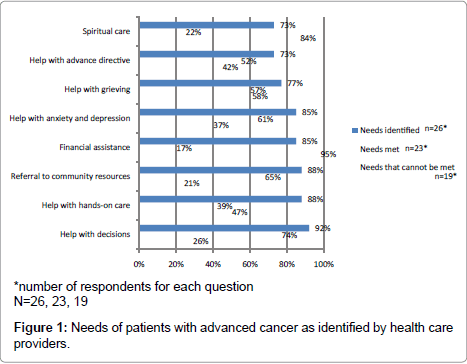

By considering positive effective factors with non-positive effective factors, we observe the following four dimensions (Figure 1). Good human relationships vs. Bad human relationships; 2) Good memories and life satisfaction vs. Bad memories and poor life satisfaction (including attainments or self-confidence); 3) Pleasure in the past and daily activities vs. Confrontation of practical problems (including worries about future); and 4) Integrative life review style vs. Nonintegrative life review style. These dimensions appear to be more predictive factors about the efficacy of spiritual wellbeing in terminal cancer patients, particularly after life review is conducted.

Practice of Life Review Interview

Life Review is usually used for elder people in institutions for them worldwide, and there have been very few empirical studies like the present study. However, terminally ill cancer patients often tell their life story until now in a hospice or a palliative care wards in Japan. Reviewing patients’ history may be the same in all of world. Although it is beginning of presenting this report that life review for terminally ill cancer patients was effective for improving spiritual well-being or psychological distress, it will be adaptable to other kind of people [26].

Comparing this therapy with another one, the Dignity Psychotherapy [27] was effective. In this therapy, patients reviewed their lives along some questions and make message to left important persons as a legacy. They recognize their near death and intend to leave legacy. However, very few Japanese seemed to receive this therapy, because they did not prefer to confront their death in Japanese culture. Few Japanese people talk about their own death and express emotion related with death. From this point of view, life review may be preferred for Japanese terminally ill patients than the Dignity Psychotherapy.

In order to conduct the life review therapy, an interviewer is required some trainings. In the above studies, the interviewer was a clinical psychologist who had many experiences of life review session. As for venue, hospice may be the most appropriate one for life review, because a room for a patient was designed for care not cure, and privacy in the room is easily protected. However, for the future life review will be conducted in home care, if an interview can visit patients’ home. We confirmed the efficacy of this therapy supported by the Cancer Research Program of the Ministry of Health Labor, and Welfare of Japan in 2010, thus this therapy may be included in a Japanese Health Care System in future.

Clinical Implication

To use a life-review method more effectively in a therapeutic clinical situation, interviewers must help patients review good human relationships and memories as well as pleasure in the past and healthy daily activities. In addition, they must help patients accept both good and bad aspects of their lives with balance in order to integrate their lives.

Finally, we may develop a new style of life review called the “Active Life Review,” in which an interviewer asks the patient to find both good human relationships and memories in bad relationships as well as search for new ways to resolve confrontational problems. Moreover, this approach helps the patient find new pleasure in life and understand that there is balance in both the good and bad aspects. In future, the author of this paper will realize this new approach in order to promote the quality of life for terminally ill cancer patients.

References

- Molzahn AE (2007) Spirituality in later life: effect on quality of life. J Gerontol Nurs 33: 32-39.

- Murata H, Morita T, Japanese Task Force (2006) Conceptualization of psycho-existential suffering by the Japanese Task Force: the first step of a nationwide project. Palliat Support Care 4: 279-285.

- Ando M, Morita T, Lee V, Okamoto T (2008) A pilot study of transformation, attributed meanings to the illness, and spiritual well-being for terminally ill cancer patients. Palliat Support Care 6: 335-340.

- Balboni TA, Vanderwerker LC, Block SD, Paulk ME, Lathan CS, et al. (2007) Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. J Clin Oncol 25: 555-560.

- Butler RN (1974) Succesful aging and the role of the life review. J Am Geriatr Soc 22: 529-535.

- Haight BK (1988) The therapeutic role of a structured life review process in homebound elderly subjects. J Gerontol 43: p40-44.

- Haight BK, Michel Y, Hendrix S (1998) Life review: preventing despair in newly relocated nursing home residents short- and long-term effects. Int J Aging Hum Dev 47: 119-142.

- Haight BK, Michel Y, Hendrix S (2000) The extended effects of the life review in nursing home residents. Int J Aging Hum Dev 50: 151-168.

- Jones ED, Beck-Little R (2002) The use of reminiscence therapy for the treatment of depression in rural-dwelling older adults. Issues Ment Health Nurs 23: 279-290.

- Haight BK, Webster JD (1995) The Art and Science of Reminiscing: Theory, Research, Methods and Applications. Taylor & Francis, Bristol, PA, USA, 179-192.

- Ando M, Tsuda A, Morita T (2007) Life review interviews on the spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 15: 225-231.

- van Wegberg B, Bacchi M, Heusser P, Helwig S, Schaad R, et al. (1998) The cognitive-spiritual dimension--an important addition to the assessment of quality of life: validation of a questionnaire (SELT-M) in patients with advanced cancer. Ann Oncol 9: 1091-1096.

- Japan Information Processing Service (2003) Word Minor. Tokyo.

- Ando M, Morita T, Okamoto T, Ninosaka Y (2008) One-week Short-Term Life Review interview can improve spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients. Psychooncology 17: 885-890.

- Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T (2010) Factors in the Short-Term Life Review that affect spiritual well-being in terminally ill cancer patients. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 12: 306-311.

- Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, et al. (1982) Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol 5: 649-655.

- Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, Cella D (2002) Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy--Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med 24: 49-58.

- Noguchi W, Ono T, Morita T, Aihara O, Hirohiko Tsujii, et al. (2004) An investigation of the reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual (FACIT-sp). Jap J Gen Hosp Psychiatry 16: 42-47.

- Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, Okamoto T, Japanese Task Force for Spiritual Care (2010) Efficacy of Short-Term Life Review interviews on the spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 39: 993-1002.

- Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, Takashi K (2012) Factors in narratives to questions in the short-term life review interviews of terminally ill cancer patients and utility of the questions. Palliat Support Care 24: 1-8.

- Hirai K, Miyashita M, Morita T, Sanjo M, Uchitomi Y (2006) Good death in Japanese cancer care: a qualitative study. J Pain Symptom Manage 31: 140-147.

- Miyashita M, Sanjyo M, Morita T, Hirai K, Uchitomi Y (2007) Good death in cancer care: a nationwide quantitative study. Ann Oncol 18: 1090-1097.

- Houmann LJ, Rydahl-Hansen S, Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Groenvold M (2010) Testing the feasibility of the Dignity Therapy interview: adaptation for the Danish culture. BMC Palliat Care 9: 21.

- Sorrell JM, Butler FR (2009) Telling life stories. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 47: 21-25.

- Greer S, Moorey S (1997) Adjuvant psychological therapy for cancer patients. Palliat Med 11: 240-244.

- Ando M, Morita T, Ahn SH, Marquez Wong F, Ide S (2009) International comparison study on the primary concer-s of terminally ill cancer patients in Short-Term Life Review Interviews among Japanese, Korean, and Americans. Palliat Support Care 7: 349-355.

- Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, Kristjanson LJ, McClement S, et al. (2005) Dignity therapy: a novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. J Clin Oncol 23: 5520-5525.

Relevant Topics

- Caregiver Support Programs

- End of Life Care

- End-of-Life Communication

- Ethics in Palliative

- Euthanasia

- Family Caregiver

- Geriatric Care

- Holistic Care

- Home Care

- Hospice Care

- Hospice Palliative Care

- Old Age Care

- Palliative Care

- Palliative Care and Euthanasia

- Palliative Care Drugs

- Palliative Care in Oncology

- Palliative Care Medications

- Palliative Care Nursing

- Palliative Medicare

- Palliative Neurology

- Palliative Oncology

- Palliative Psychology

- Palliative Sedation

- Palliative Surgery

- Palliative Treatment

- Pediatric Palliative Care

- Volunteer Palliative Care

Recommended Journals

- Journal of Cardiac and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Palliative Care & Medicine

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Journal of Pediatric Neurological Disorders

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry: Open Access

- OMICS Journal of Radiology

- The Psychiatrist: Clinical and Therapeutic Journal

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14687

- [From(publication date):

specialissue-2012 - Apr 02, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 10093

- PDF downloads : 4594