Research Article Open Access

Factors Associated with Delivery of Very Low Birth Weight Infants in Nonlevel III Neonatal Intensive Care Units

Ingrid Mburia1,2*and Wei Yang1,31Environmental Sciences and Health, Graduate Program, University of Nevada, Reno, Nevada, USA

2Office of Public Health Informatics and Epidemiology, Nevada Division of Public and Behavioural Health, Carson City, Nevada, USA

3School of Community Health Sciences, University of Nevada, Reno, Nevada, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Ingrid Mburia

Environmental Sciences and Health

Graduate Program, University of Nevada

Nevada, USA

Tel: 17754616600

E-mail: imburia@nevada.unr.edu

Received date: July 31, 2016; Accepted date: October 28, 2016; Published date: October 31, 2016

Citation: Mburia I, Yang W (2016) Factors Associated with Delivery of Very Low Birth Weight Infants in Non-level III Neonatal Intensive Care Units. J Preg Child Health 3:290. doi:10.4172/2376-127X.1000290

Copyright: ©2016 Mburia I, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Pregnancy and Child Health

Abstract

Introduction The objective of this study was to examine the factors that influence delivery of very low birth weight infants in non-level III neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) in Nevada. Maternal, infant, behavioural, clinical and geographical factors were assessed. Methods A population-based study was conducted using electronic birth records from 2010-2014 for 980 singleton liveborn infants weighing 500 g-1499 g. Multiple logistic regression analyses were conducted to assess the risk factors associated with delivery in non-level III NICUs. SaTScan was used to identify spatial clusters of VLBW neonates and ArcGIS was used to map the distance from the mother's residence to the nearest level III NICU. Results During the study period, 2010-2014, 88.6% of the infants were born in a level III hospital. Of these, half (50.5%) required ventilation immediately and about quarter (24.3%) were transferred within 24 h of delivery. Majority of the mothers (85.6%) lived within 10 miles to the nearest level III NICU. About half (46.8%) of the women who delivered in a non-level III NICU were overweight or obese, 10% smoked during pregnancy and 26.1% received late prenatal care. The most common method of delivery was via caesarean section (57.7%). Factors associated with delivery of a VLBW infant in a non-level III hospital included: distance (>50 miles), race/ethnicity (Asian and Black) and education (<12 years). Conclusion In this study, 11.3% of the VLBW deliveries took place in a non-level III NICU even though majority (85.6%) of the mothers lived less than 10 miles from the nearest level III NICU. Transportation and access to specialized health care services may be a barrier to women of certain race/ethnic groups and low socioeconomic status. Providing transportation to women in rural areas and those from low-income neighbourhoods in urban areas could increase access to risk appropriate care.

Keywords

Perinatal regionalization; Very low birth weight; Prenatal care; Level III NICU; Population-based study; Spatial mapping; Cluster analysis

Introduction

Medical advancements, extensive research, and numerous prevention strategies and policies have enabled very low birth weight (VLBW; less than 1,500 g) babies to live and survive beyond the first few days of life. However, VLBW infants require specialized care at birth, have a higher likelihood of dying, and face both short and long term disabilities compared to infants weighing ≥ 1500 g.

VLBW infants who survive are afflicted by several morbidities including lower respiratory tract infections, intellectual and neurological problems such as cerebral palsy and intraventricular haemorrhage, gastrointestinal problems [1,2] retinopathy, chronic pulmonary disease, developmental delay [3,4] and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) [5].

Perinatal regionalization was developed to ensure that women who are at-risk of delivering a VLBW baby have timely access to riskappropriate neonatal and obstetric care. In addition, when fully optimized, regionalized perinatal systems could play a role in reducing maternal and infant morbidity and mortality. However, there is growing concern that the prevalence of VLBW infants being born in level III hospitals or subspecialty perinatal centres is decreasing.

The US Department of Health and Human Services outlines access to appropriate health care services as one of the Healthy People 2020 goals for Maternal-Infant-Child Health (MICH). The goal of MICH-33 is to increase the proportion of very low birth weight infants born at level III hospitals or subspecialty perinatal centers to 83.7% by 2020. Nevada has neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) with different levels of care for very preterm and VLBW infants. However, the state has a unique topography with vast distances that separate the rural communities from the urban areas. In addition to geographical barriers, access to hospitals and health care services in the rural and frontier counties of the state is confounded by a shortage of specialty health care providers. With these barriers in mind, our study sought to address the following research questions:

• Does distance from maternal residence determine the hospital of delivery for VLBW infants?

• What are the risk factors associated with a VLBW infant not being born at a level III NICU?

• Are there any clusters of VLBW deliveries in non-level III NICUs in Nevada?

Although there are many studies focusing on outcomes of VLBW infants by the level of neonatal care at hospital of birth, studies solely focusing on the factors related to VLBW infants born in a non-level III hospital are scarce.

Methods

Study sample and data source

We conducted a population-based retrospective study of 980 singleton infants of VLBW using data from the Nevada electronic birth records (birth certificate data) for the years 2010-2014. We obtained the mothers and infants characteristics as well as the hospital where the delivery occurred the birth certificates. The main outcome of interest was birthing facility or hospital with a NICU designated as level III. We restricted our analysis to live singleton births that occurred to women who were Nevada residents. We included only live-born infants in this study because babies who are born dead may have a broad range of factors that could be different from those born alive. To be consistent with existing research [6-8] we excluded deliveries that occurred at home or in out of state hospitals, multiple births, infants who weighed <500 g, infants <20 weeks of gestation, and births with missing information on covariates. Neonates weighing <500 g and <20 weeks of gestation were excluded because a large proportion do not survive past their first day of life. We obtained approval for this study from the University of Nevada, Reno, and Institutional Review Board.

Infant Factors

We included the following infant characteristics associated with VLBW: infant’s birth weight (500 g–750 g, 751 g–1000 g, 1001 g–1250 g, 1251 g–1499 g); gestational age in weeks (22–24, 25–27, 28–30, 31– 33, 34+); sex (male, female); and clinical factors including: selected congenital anomalies; infant transfer within 24 h of delivery; and whether the infant received assisted ventilation immediately or for longer than six hours. We used the obstetric estimate (OE) to determine gestational age at delivery. OE of gestation is “the best obstetric estimate of the infant’s gestation in completed weeks based on the birth attendant’s final estimate of gestation” [9].

Maternal Factors

We included the following maternal sociodemographic characteristics: age (<20, 20-34, 35+); race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Asian, Native American/American Indian, non- Hispanic white); education in years (<12, 12, >12); payment source for delivery (Medicaid, private insurance, self-pay, other); marital status (married, not married); area of residence (rural, urban); maternal behaviours (tobacco, alcohol and drug use during current pregnancy, timeliness of prenatal care (first, second and third trimester); maternal medical risk factors (BMI, <18.5, 18.5-24.9, 25.0-29.9, >30); prepregnancy diabetes, gestation diabetes, chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension, premature rupture of membranes, abruptio placenta, placenta previa, delivery method (cesarean or vaginal); and whether the mother was transferred for delivery.

Community Level Factors

Neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) level information

We obtained the hospital information on where the VLBW deliveries took place from the birth certificates and derived the NICU designation from each hospital’s website. In cases where the NICU level was not available, we called the hospital to obtain the information. NICU levels I, II and III designations were developed in 1976 [10] and expanded in 1993 to include basic, specialty, and subspecialty care. Level I units, also known as well newborn nurseries, provide basic care to neonates with low risk. Level II units are considered ‘specialty’ units that provide care to infants with moderate risk of complications resulting from prematurity or illness. Level II units are further subdivided into IIA and IIB depending on their capacity to offer assisted ventilation services. Level III units are subspecialty NICUs with appropriate staff and equipment to provide the neonate with life support if necessary. We classified the hospitals as level III NICU and non-level III NICU. Nevada uses level I, II and III for its NICU designations.

Spatial cluster detection

We geocoded the mother’s physical address and the address of the delivery hospital at the zip code centroid level using ArcGIS software (ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA) [11]. We used saTScan V.9.4 [12] to identify spatial clusters of VLBW neonates delivered in a non-level III NICU in Nevada. We defined a spatial disease cluster as an area with unusually elevated VLBW incidence rate of VLBW deliveries. To account for the underlying spatial inhomogeneity of our population, we used the total number of live births in the study period. We used saTScan to conduct our spatial clustering analysis because it has been widely used by researchers to detect clusters for various diseases and conditions using cases, controls, and the coordinate location [13-16].

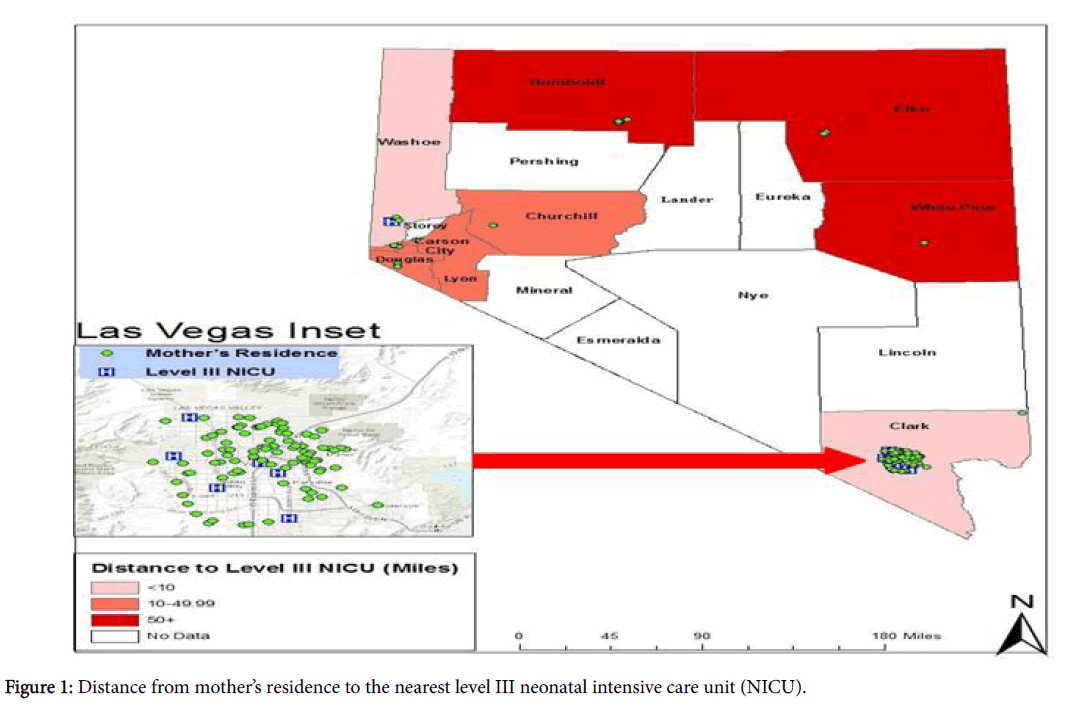

Distance calculation

To measure absolute distance, we calculated the shortest straightline distance from the mother’s residential zip code to the nearest hospital with a level III NICU using the near distance tool in the geographic information system software ArcGIS 10.3.1 (ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA). Straight-line distances have been used in research to determine whether distance from a particular location has an effect on travel choices [17]. Distance to the nearest level III NICU was calculated for each set of birth record coordinates and categorized as <10 miles, 10-49.9 miles, and 50+ miles. We based the cutoffs on distances on the results of distance in our study. We used distance to measure access to health care resources (hospitals with a NICU designated as level III) for mothers giving birth to VLBW infants.

Statistical Analysis

We described participant characteristics using frequency analyses. We used multiple logistic regression analyses to model the risk of VLBW delivery in a non-level III NICU as a function of infant and maternal characteristics, clinical conditions, and health behaviours described above. We conducted bivariate analysis and calculated odds ratios. We used the forwards selection with a p-value criterion of <0.05 to determine the covariates to include in the models. We adjusted for the covariates in all the models and calculated the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for these associations. In the first model, we controlled for demographic variables and distance to the nearest level III NICU to explore the mechanism by which delivery in non-Level III NICU is impacted by these factors. The second model assessed the independent roles played by behavioural factors such as smoking, alcohol, and drug use during pregnancy. Tobacco and alcohol use were correlated therefore we combined the two variables together to form a single variable. The final model, we evaluated the role of maternal obstetric factors. We used SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) to conduct the analyses in this study.

We used the Bernoulli model to evaluate clusters for VLBW in Nevada. The model requires input of cases (VLBW infants born in a non-level III NICU), controls (VLBW infants born in a level III NICU) and the geocoded locations. We used the mother’s residential address to obtain the geospatial information and used the purely spatial analysis of the Bernoulli model to identify clusters with elevated rates. However, we only report clusters smaller than 50 per cent of population at risk and those that were statistically significant (p-value <0.05). This model can only evaluate clusters at 50 percent of the population and populations outside this scale would yield results that are not statistically significant [12].

Results

The descriptive statistics for infant and maternal characteristics by NICU level are provided in Table 1.

| Characteristics | Level III NICU | Non-level III NICU |

|---|---|---|

| n=869 (%) | n=111 (%) | |

| Infant Characteristics | ||

| Very Low Birth Weight (g) | ||

| 500-750 | 168 (17.1) | 14 (12.7) |

| 751-1000 | 202 (20.6) | 30 (27.0) |

| 1001-1250 | 246 (25.1) | 25 (22.5) |

| 1251-1499 | 253 (25.8) | 42 (37.8) |

| Gestation (weeks) | ||

| 22-24 | 136 (15.7) | 11 (9.9) |

| 25-27 | 237 (27.3) | 30 (27.0) |

| 28-30 | 300 (34.5) | 34 (30.6) |

| 31-33 | 153 (17.6) | 24 (21.6) |

| 34+ | 43 (4.9) | 12 (10.8) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 463 (53.3) | 56 (50.5) |

| Female | 406 (46.7) | 55 (49.6) |

| Required assistance ventilation immediately | ||

| Yes | 269 (31.0) | 56 (50.5) |

| No | 600 (69.0) | 55 (49.6) |

| Received assistance ventilation for = 6 hours | ||

| Yes | 207 (23.8) | 44 (39.6) |

| No | 662 (76.2) | 67 (60.4) |

| Congenital anomaly | ||

| Yes | 37 (4.3) | 8 (7.2) |

| No | 832 (95.7) | 103 (92.8) |

| Infant transferred within 24 hours of delivery | ||

| Yes | 8 (0.9) | 27 (24.3) |

| No | 861 (99.1) | 84 (75.7) |

| Maternal Characteristics | ||

| Age (years) | ||

| <20 | 75 (8.6) | 11 (9.9) |

| 20-34 | 616 (70.9) | 85 (76.6) |

| 35+ | 178 (20.5) | 15 (13.5) |

Table 1: Maternal and infant characteristics by NICU Level: Nevada, 2010-2014.

Infant characteristics

There were eight hospitals designated as level III NICU and 12 hospitals with a NICU level I, II or nursery only (non-level III NICU). During the study period (2010–2014), 980 singleton infants weighing between 500 g–1499 g and with gestational ages of 22–34+ weeks met the inclusion criteria. Majority (88.6%), were born in a hospital with a level III NICU and over half (52.9%) were male. About a third (30.1%) of the infants weighed between 1251-1499 g. Seventy per cent of all the infants were delivered via caesarean section. Of all the infants born in a non-level III NICU, half (50.5%) required ventilation immediately and about quarter (24.3%) were transferred within 24 h of delivery.

Maternal characteristics

Majority of the mothers (71.5%) in the study were between the ages of 20-34. The race/ethnic breakdown of the mothers was: Hispanic (35.6%), White non-Hispanic, (34.0%), Black non-Hispanic, (19.5%), Asian, (10.0%) and Native American (0.8%). Most of the women (95.3%) lived in an urban area and close to half (46.0%) had more than high school education. More than half (56.8%) were unmarried, about a third (30.6%) were Black and 63.1% used other means of payment for their delivery. In both groups, majority of the mothers lived in an urban area that was within 10 miles to the nearest level III NICU.

The behavioural and medical risk factors of mothers who delivered in a non-level III NICU are presented in Table 2. About half (46.8%) of the women who delivered in a non-level III hospital were overweight or obese (BMI 25-29.9 and >30, respectively) and about 10% smoked during pregnancy. One of the Healthy People 2020 objectives that relate to maternal, infant and child health is to increase abstinence from cigarette smoking among pregnant women to 98.6% by 2020. Even though this target is for the entire population of women giving birth, the smoking rate for this subset of the population is high. The National Committee for Quality Assurance and the Institute of Medicine, among others, have stipulated that maternal and fetal outcomes are greatly improved when prenatal care is received in the first trimester. However, more than a quarter (26.1%) of the women who delivered in a hospital that is not designated as level III received late prenatal care (in the second or third trimester). The most common method of delivery was by caesarean section (57.7%).

| Characteristics | Level III NICU n=869 (%) |

Non-Level III NICU n=111 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal Behaviors | ||

| BMI | ||

| <18.5 | 38 (4.4) | 9 (8.1) |

| 18.5-24.9 | 355 (40.9) | 50 (45.1) |

| 25-29.9 | 212 (24.4) | 23 (20.7) |

| >30 | 264 (30.4) | 29 (26.1) |

| Tobacco and alcohol use during pregnancy | ||

| None | 786 (90.5) | 97 (87.4) |

| Tobacco | 73 (8.4) | 11 (9.9) |

| Alcohol | 5 (0.6) | 1 (0.9) |

| Alcohol and tobacco (combined) | 5 (0.6) | 2 (1.8) |

| Drug use 1 | ||

| Yes | 258 (29.7) | 38 (34.2) |

| No | 611 (70.3) | 73 (65.8) |

| Medical Risk Factors | ||

| Pre-pregnancy diabetes | ||

| Yes | 24 (2.8) | 3 (2.7) |

| No | 845 (97.2) | 108 (97.3) |

| Gestational diabetes | ||

| Yes | 54 (6.2) | 7 (6.3) |

| No | 815 (93.8) | 104 (93.7) |

| Chronic hypertension | ||

| Yes | 61 (7.0) | 4 (3.6) |

| No | 808 (93.0) | 107 (96.4) |

| Gestational hypertension | ||

| Yes | 108 (12.4) | 12 (10.8) |

| No | 761 (87.6) | 99 (89.2) |

| Trimester prenatal care began | ||

| First | 702 (80.8) | 82 (73.9) |

| Second | 156 (18.0) | 26 (23.4) |

| Third | 11 (1.3) | 3 (2.7) |

Table 2: Maternal behaviours and medical risk factors by NICU Level: Nevada, 2010-2014 (Abbreviations: NICU: Neonatal Intensive Care Unit; VLBW: Very Low Birth Weight; BMI: Body Mass Index).

Results of the adjusted and unadjusted odds ratios of the factors related to VLBW delivery in a non-Level III hospital are displayed in Table 3. The final model controlled for maternal age, maternal race ethnicity, and high school graduation, payment source for delivery, prenatal care, tobacco, alcohol, and drug use, gestational diabetes and distance to closest level III NICU. The regression analyses showed that women who lived more than 50 miles from a level III NICU, adjusted odds ratio (AOR)=3.98, 95% CI, 1.58–10.03, had higher odds of delivering a VLBW infant in a non-level III NICU compared to women who lived within 50 miles of a level III NICU. Delivery of a VLBW neonate in a non-level III NICU was also associated with: Asian race AOR=2.30 CI, 1.12–4.73, non-Hispanic Black race AOR=2.37, 95% CI, 1.32–4.26 and less than 12 years of education, AOR=2.83, 95% CI, 1.52-5.27.

| Characteristics | Level III NICU n=869 (%) |

Non-Level III NICU (n=111) (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal Behaviors | ||

| BMI | ||

| <18.5 | 38 (4.4) | 9 (8.1) |

| 18.5-24.9 | 355 (40.9) | 50 (45.1) |

| 25-29.9 | 212 (24.4) | 23 (20.7) |

| >30 | 264 (30.4) | 29 (26.1) |

| Tobacco and alcohol use during pregnancy | ||

| None | 786 (90.5) | 97 (87.4) |

| Tobacco | 73 (8.4) | 11 (9.9) |

| Alcohol | 5 (0.6) | 1 (0.9) |

| Alcohol and tobacco (combined) | 5 (0.6) | 2 (1.8) |

| Drug use 1 | ||

| Yes | 258 (29.7) | 38 (34.2) |

| No | 611 (70.3) | 73 (65.8) |

| Medical Risk Factors | ||

| Pre-pregnancy diabetes | ||

| Yes | 24 (2.8) | 3 (2.7) |

| No | 845 (97.2) | 108 (97.3) |

| Gestational diabetes | ||

| Yes | 54 (6.2) | 7 (6.3) |

| No | 815 (93.8) | 104 (93.7) |

| Chronic hypertension | ||

| Yes | 61 (7.0) | 4 (3.6) |

| No | 808 (93.0) | 107 (96.4) |

| Gestational hypertension | ||

| Yes | 108 (12.4) | 12 (10.8) |

| No | 761 (87.6) | 99 (89.2) |

| Trimester prenatal care began | ||

| First | 702 (80.8) | 82 (73.9) |

| Second | 156 (18.0) | 26 (23.4) |

| Third | 11 (1.3) | 3 (2.7) |

Table 3: Maternal behaviours and medical risk factors by NICU Level: Nevada, 2010-2014.

The distance from mother’s residence to the nearest Level III NICU is spatially presented in Figure 1. As mentioned previously, majority of the mothers who did not deliver a VLBW infant a level III NICU lived in Clark County and were within 10 min from the nearest level III NICU. The distribution of our sample is proportional to the population makeup of the Nevada. According to the 2014 population estimates provided by the Nevada State Demographer, 72.5% of the state’s population resides in Clark County, 15.5% in Washoe County, and 10.1% in the rural and frontier areas of the state. Even though the rural and frontier counties are the least populated, they encompass 86.9% of Nevada’s land mass [18]. Congruent with the population density; six of the eight hospitals designated as level III are located in Clark County while the other two are located in Washoe County. There are no levels III NICUs in the rural counties leaving the residents to travel to Washoe or Clark County or to neighbouring states such as California, Utah or Arizona to obtain health services.

We used cluster analysis to detect clusters in mothers who gave birth to VLBW babies in non-level III NICUs. The Bernoulli SaTScan statistic detected two clusters that were statistically significant (pvalue< 0.01). The clusters had relative risks of 3.00 and 5.24 respectively. Clustering was correlated to the number of deliveries in a zip code and all of the clusters were located in Clark County which had the highest number of live births in Nevada. This was not unexpected as 72.5% of the state’s population lives in Clark County.

Discussion

Our study sought to assess whether distance from maternal residence was a risk factor for delivering a VLBW infant in a hospital that was not designated as level III. We found that long distance had increased odds of delivery in a non-level III hospital after controlling for maternal demographics, behavioural, and medical risk factors. These findings are consistent with the geographic makeup of Nevada whereby rural/frontier areas are separated by vast distances from the urban areas. However, our findings differ from those of Ansariadi et al. [19] and Pilkington et al. [20,21] who reported that distance was not a factor in delivery of an infant in a hospital. It is worth noting that these studies were conducted in France and Indonesia thus may not be comparable to the US. Our study found that 11.3% of the VLBW deliveries did not take place in a hospital designated as level III. It is interesting to note that out of these, majority (85.6%) lived less than 10 miles away from a level III NICU. Since majority of these mothers lived in Clark County, transportation and access to specialized health care services such as those found in a level III NICU may be a barrier for women of low socioeconomic status.

Race/ethnicity has been linked to low birth weight and poor access to health services [22-28]. In our study, Asians and non-Hispanic Blacks had higher odds of delivering VLBW infants in hospitals that were not designated as high-risk even after controlling for important covariates. In the US, the rate of uninsured immigrants who are not citizens is double that of the native born population with a higher number of race/ethnic minorities lacking citizenship [29]. Contrary to national statistics, non-citizen Asians residing in Nevada defy these odds because they have a lower uninsured rate (4.8%) compared to the US Asian Americans (7.2%) [27]. However, when examined by ethnicity, it has been shown that some Asian/Pacific Islander groups have very high uninsured rates [28]. Our study did not stratify Asians by nativity because of small numbers but this could be an area for further research since Asian women of different ancestral origins may exhibit different characteristics.

Education level is often used as a proxy for socioeconomic status (SES) which in turn is used as measure for access to health care services. We had information on the mother’s income. Therefore, we used individual-level SES measures rather than the census tract level data. Studies [30-32] have shown an association between VLBW and low SES. Our study was congruent with those findings and showed that women with less than high school education had increased odds of delivering VLBW infants in a non-level III NICU compared to women with more than high school education. These results are also consistent with Bronstein et al. [7], who used birth records from the state of Alabama and showed that having less than high school education was associated with VLBW delivery in a hospital without a NICU.

Early prenatal care is a critical aspect in preventing very low birth weight. Lack of prenatal care is associated with low birth weight and infant mortality [30,33]. Guillory et al. [24] found that women who did not receive timely prenatal care were more likely to deliver low birth weight babies. In one of the models (results no shown), we examined timeliness of prenatal care and the results indicated that women who received late prenatal care had higher odds of deliver VLBW infants in a hospital without a level III NICU compared to women who received prenatal care in the first trimester. Timely prenatal care is essential because during prenatal visits, both mother and baby’s health can be examined to identify any underlying health conditions that could influence the outcome of the pregnancy.

Study limitations and strengths

The clusters found in Clark County cannot be dismissed as chance occurrence and would require further evaluation to determine associated mechanisms. In this study, we were able to adjust for some of the known risk factors for VLBW such as race/ethnicity and SES with education and method of payment as proxies for SES. The spatial analyses also showed that mothers in the rural areas did not have access to level III hospitals or subspecialty perinatal centers for delivery of VLBW due to long distances from their residence to the level III NICUs. The results showed that even though Clark County had the most level III NICUs, some mothers with a VLBW baby did not deliver their babies in these hospitals. Public Health Programs in the State and Clark County should work closely with health care providers to ensure that barriers for access to quality health care are addressed.

Our study was not able to control for other known or hypothesized risk factors for VLBW due to unavailability of data such as genetic disposition/family history and environmental factors. The authors recognize that for these variables to be truly associated with the existence of a cluster they have to be true risk factors and the population at risk must also be proportionately higher where the cluster is detected.

Therefore, this presents an opportunity for further research. Another limitation of our study is that birth certificate data is selfreported and some undesirable risk behaviours such as smoking during pregnancy and illicit drug use are under-reported. Nonetheless, the research provides a critical step in informing and explaining existing disparities in health care access to specialized NICUs in Nevada. The other limitation of our study is difficulty in determining accuracy of hospitals designated as facilities for high-risk neonates. Hospitals self-report their level of perinatal care and there is no regulatory body to enforce the designations. The levels of neonatal care developed by March of Dimes clearly stipulate the requirements for a facility to be designated as high-risk for neonates. However, hospitals may change or discontinue NICU services making it difficult to keep up with the changes. Enforcing NICU designations would create standardization and ensure women and children are receiving the appropriate health care services.

Conclusion

This study illustrates the importance of evaluating potential associations between distance to the nearest level III NICU, race, education and cluster analysis when examining access to health care services. Research has shown that race and ethnicity is intertwined with SES [22-26] and these factors influence the choice of health care facilities and services. However, there is need to untangle these relationships through regression analysis as well as innovative methods such as spatial mapping and cluster analysis. These strategies will ultimately provide information to develop referral and transport strategies especially for mothers living in rural and frontier areas in order to ensure that every mother and new-born receives risk appropriate care and has access to quality health care services.

References

- Eichenwald EC, Stark AR (2008) Management and outcomes of very low birth weight. N Engl J Med 358: 1700-1711.

- Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, Shankaran S, Laptook AR, et al. (2010) Neonatal outcomes of extremely preterm infants from the NICHD neonatal research network. Pediatrics 126: 443-456.

- Richmond IN, Diaz LM, Dinsmoor MJ, Lin PY (2001) Honourable mention preventable risk factors for the delivery of very low birth weight infants 8: 20-23.

- Chang HY, Sung YH, Wang SM, Lung HL, Chang JH, et al. (2015) Short- and long-term outcomes in very low birth weight infants with admission hypothermi A. PLoS One 10: e0131976.

- Sarah SB (2010) Can low birth weight is prevented? Family Planning Perspectives 17: 112-118.

- Lemons JA, Bauer CR, Oh W, Korones SB, Papile LA, et al. (2001) Very low birth weight outcomes of the national institute of child health and human development neonatal research network, January 1995 through December 1996. NICHD neonatal research network. Paediatrics 107: 1.

- Bronstein JM, Capilouto E, Carlo WA, Haywood JL, Goldenberg RL (1995) Access to neonatal intensive care for low-birth weight infants: The role of maternal characteristics. Am J Public Health 85: 357-361.

- Dunlop AL, Salihu HM, Freymann GR, Smith GK, Brann AW (2010) Very low birth weight births in Georgia, 1994-2005 : Trends and racial disparities. Matern Child Health J 15: 890-898.

- Statistics NC (2012) Guide to completing the facility worksheets for the certificate of live birth and report of fetal death: 1-51.

- Lemons JA, Bauer CR, Oh W, Korones SB, Papile LA, et al. (2004) American academy of pediatrics. Levels of neonatal care. Pediatrics 114: 1341-1347.

- Booth B, Mitchell A (2006) Getting started with ArcGIS GIS by ESRI 260.

- Kulldorff BM (2015) SaTScan User Guide 4: 1-113.

- Westercamp N, Moses S, Agot K, Ndinya-Achola JO, Parker C, et al. (2010) Spatial distribution and cluster analysis of sexual risk behaviors reported by young men in Kisumu, Kenya. Int J Health Geogr 9: 24.

- Kulldorff M, Feuer EJ, Miller BA, Freedman LS (1997) Breast cancer clusters in the northeast United States: A geographic analysis. Am J Epidemiol 146: 161-170.

- Martinez AN, Mobley LR, Lorvick J, Novak SP, Lopez AM, et al. (2014) Spatial analysis of HIV positive injection drug users in San Francisco, 1987 to 2005. Int J Environ Res Public Health 11: 3937-3955.

- Iii CEF (2013) Obesity in the built environment : A spatial analysis of two Canadian Metropolitan areas by.

- McGuirk MA, Porell FW (1984) Spatial patterns of hospital utilization: The impact of distance and time. Inquiry 21: 84-95.

- (2015) Nevada rural and frontier health data book, seventh edition.

- Ansariadi A, Manderson L. (2015) Antenatal care and women’s birthing decisions in an Indonesian setting: Does location matter? Rural Remote Health 15: 1-17.

- Pilkington H, Blondel B, Drewniak N, Zeitlin J (2014) Where does distance matter? Distance to the closest maternity unit and risk of foetal and neonatal mortality in France. Eur J Public Health 24: 905-910.

- Pilkington H, Blondel B, Drewniak N, Zeitlin J (2012) Choice in maternity care: Associations with unit supply, geographic accessibility and user characteristics. Int J Health Geogr 11: 35.

- Radcliff E, Delmelle E, Kirby RS, Laditka SB, Correia J, et al. (2015) Factors associated with travel time and distance to access hospital care among infants with spina bifida. Matern Child Health J 20: 205-217.

- Babitsch B, Gohl D, von-Lengerke T (1974) A Framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res 9: 208-220.

- Guillory VJ, Lai SM, Suminski R, Crawford G (2015) Low birth weight in kansas. J health care poor underserved 26: 577-602.

- Valero De Bernab J, Soriano T, Albaladejo R, Juarranz M, Calle ME, et al. (2004) Risk factors for low birth weight: A review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 116: 3-15.

- Howell EA, Hebert P, Chatterjee S, Kleinman LC, Chassin MR (2008) Black/white differences in very low birth weight neonatal mortality rates among New York City hospitals. Pediatrics 121: 407-415.

- Brawley OW, Freeman HP (1999) Race and outcomes: Is this the end of the beginning for minority health research? J Natl Cancer Inst 91: 1908-1909.

- Reagan PB, Salsberry PJ (2005) Race and ethnic differences in determinants of preterm birth in the USA: Broadening the social context. Soc Sci Med 60: 2217-2228.

- Castelló A, Río I, Martinez E, Rebagliato M, Barona C, et al. (2012) Differences in preterm and low birth weight deliveries between spanish and immigrant women: Influence of the prenatal care received. Ann Epidemiol 22: 175-182.

- Kramer MS, Séguin L, Lydon J, Goulet L (2000) Socio-economic disparities in pregnancy outcome: Why do the poor fare so poorly? Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 14: 194-210.

- Wang Y, Beydoun MA (2007) The obesity epidemic in the United States--gender, age, socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and geographic characteristics: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Epidemiol Rev 29: 6-28.

- Meyer PA, Yoon PW, Kaufmann RB (2013) Introduction: CDC health disparities and inequalities report - United States, 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ 62: 3-5.

- Andreea AC, Berg CJ, Syverson C, Seed K, Bruce FC (2015) Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2006-2010. Obstet Gynecol 125: 5-12.

Relevant Topics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 11654

- [From(publication date):

October-2016 - Jul 16, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 10674

- PDF downloads : 980