Factor Influencing HIV Care Continuum among People Living with HIV in Western Kenya

Received: 23-Dec-2017 / Accepted Date: 27-Dec-2017 / Published Date: 29-Dec-2017 DOI: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000579

Abstract

HIV infection is associated with a lot of morbidity and mortality especially in high burden countries in Sub Saharan Africa. Despite great progress in improving HIV testing and access to ART for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in Sub Saharan Africa, ART coverage remains low and majority of people with HIV are still unaware of their status. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the predictors of HIV continuum care in Gucha Sub County in Kisii, an area with a high HIV prevalence of 8.9% in Kenya. This was carried out through a cross-sectional study and participants were randomly selected amongst HIV positive clients in comprehensive care centers and community based support groups in Gucha. Data was collected using a semi structured interview guided questionnaires Categorical data was analysed using Chi-Square. SPSS was used to compute the statistics. This study revealed that majority 97 (80.17%) of the participants were female since men are less likely to report and enroll in HIV care when they test HIV positive. Male tend to seek health care when severely ill. The study results show that participants had low HIV knowledge to make informed choice only 21 (17.36%) had informed choice. This study reveals that the main determinants of ART uptake are associated with patient's education, food by prescription, site location for patient support centre and privacy. Therefore, there is need to enhance the uptake of HIV care among PLWHA an interventions targeting multiple stage must be designed, which may improve linkages throughout the HIV care continuum in the short and long term. Strategies to improve Identification of the undiagnosed PLHIV and linking them to HIV care and management is a priority in order to achieve UNAIDS goal by 2020.

Keywords: HIV; Care continuum; People; Antiretroviral therapy; Human immunodeficiency virus

Introduction

Human Immunodeficiency virus (HIV) care continuum sometimes referred to as the HIV treatment cascade includes diagnosis, getting and staying in medical care, get on antiretroviral therapy and viral suppression (very low level of HIV in the body) [1].

Several studies have shown that antiretroviral therapy (ART) is successful when it reduces the viral load of a person living with HIV to undetectable levels in their blood and they are more likely to live a long and healthy life [2] and less likely to pass HIV to others [3] for a person living with HIV to achieve an undetectable viral load, they need access to a continuum of services (HIV testing and diagnosis, linkage to appropriate medical care (and other health services), support while in care, access to antiretroviral treatment if and when they are ready, and support while on treatment).

Therefore, effective HIV treatment and prevention programs requires that HIV counseling and testing (HTC) services and linkages of patients to HIV care and support to reduce HIV associated morbidity and mortality [4], especially in sub-Saharan Africa where 1.5 million cases of new HIV infection occur annually [5,6]. However, in this region only a third of adults have tested for HIV and even among those who have tested positive only a few are on ART [4,7]. This has been attributed to poor linkage to care following HIV testing [8-10]. Therefore, to reduce morbidity and mortality associated there is a need to promptly link patients to care following HIV testing.

Human immunodeficiency virus testing coverage varies between countries and even within countries [4,11]. For example, HIV testing coverage in Kenya in men is around 36% while for women it is around 47% and there has been a steady increase for adults tested for HIV from 860,000 in 2008 to 6.4 million in 2013 [12]. However, national coverage may mask intra-county variation in uptake of HTC [4]. Therefore, to achieve widespread testing and initiation into antiretroviral therapy, there is a need to overcome challenges associated with low HTC uptake like economic costs to patients in terms of transportation, waiting time, concerns about confidentiality, low perceived risk of HIV infection and policy on eligibility to antiretroviral therapy [13]. This has been achieved through up scaling of community-based HTC services [14], that has not only led to widespread testing but also increased linkage to HIV support and care [15]. Moreover, studies have shown that there is high acceptability of community HTC services that has led to prompt linkage to HIV care and consequently viral load suppression relative to facility based HTC services [16-18].

Even though scaling up of ART has greatly reduced HIV associated mortality [4,19]. The mortality rates are still considerably higher in poor resource countries relative to more industrialized nations partly due to late initiation into ART therapy [7]. Moreover, the risk factors for late initiation to ART therapy is male sex, young age, lower education level, unemployment and facility based HTC [20,21], indicating that identification of factors that predicts late ART initiation are critical in formulating strategies and policies to address this issue. Kenya had a HIV prevalence of 5.6% in 2012 and the number of people living with HIV on ART estimated to be 880,000 with adults constituting 85% of this population [11]. More importantly HIV counseling and testing among pregnant women is at 92.20%, coverage of PMTCT ARV at 70.60%, number of infants born to HIV positive mother receiving a virological test for HIV within 2 months of birth at 45%, the eligible PLHIV on ART at 80% and a retention rate about 92% within the first month [12,20]. Despite this achievement at national level there is a paucity of data on the factors that may be leading to poor linkage to HIV care especially at county level although there is geographical variation in HIV prevalence [11]. The objective of this analysis is to determine the context-specific predictors of HIV continuum of care among PLWHA in western Kenya in order to help formulate policies and interventions that will lead to up scaling of optimal HIV care and treatment programs.

Methods

Study setting and design

This study utilized a cross sectional study design to collect data from patients aged ≥ 18 years living with HIV/AIDS who were on HIV care and treatment at Gucha Sub-County Hospital who were captured in the patient support centre register from 2005 to December 2015. This study was carried out in Gucha Sub-County Hospital in Kisii County in western Kenya, where the adult HIV prevalence is 8.9% [11]. The hospital has a hundred bed capacity hospital less than 100 beds with a catchment area of about 40,000 people. HIV care and treatment clinics were introduced in the hospital in 2005.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethical Review Board of University of East Africa Baraton (REC.UEAB/18/02/2016).

Data collection

A semi structured interview guide questionnaires and two community based Focused Group Discussions were used as tools for the survey. Some secondary data were also extracted from the hospital files. The questions focused to address the study objectives. The questionnaires were filled by a trained research assistant and pre testing of the questionnaires was done at Oresi Sub-County Hospital in Kisii to validity the questionnaires. Changes and comments were incorporated according to recommendations from the participants from the pilot study before actual data collection.

Data management and statistics

Quality and completeness was ensured through checking missing variables and cleaning data by editing. Association was determined by use of chi-square, multivariate logistic regression was used to identify significant predictors of HIV care of continuum uptake.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

A total of 121 individuals diagnosed with HIV between 2005 and 2015 were analyzed for entry into care (Table 1) of 121 patients enrolled into the study 47.11% aged between 31-50 years, 33.88% were aged between 25-30 years and 15.70% were over 51 years, 3.31% did not respond. There were comparatively more females (80.2%) relative to males (19.8%). A greater percentage was from rural (50.4%) while 36.4% resided in urban areas and 13.22% did not reveal their residence. In terms of marital status, a majority of the study participants were married (53.7%), 10.8% were single, 12.4% separated, 20.7% were widows/widowers while 2.5% did not reveal their marital status. In addition, 42.98% had secondary education, 42.15% had primary education, 5.79 had college education, and 6.61% had no education while 2.48% did not reveal their level of education. A majority (93.4%) of the study participants were Christians and farmers (62.81%). A majority of the patients (34%) were tested at MCH clinics while the main reason for HIV testing was pregnancy (33.06%).

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| 25-30 | 41 (33.88) |

| 31-50 | 57 (47.11) |

| >51 | 19 (15.70) |

| Non response | 4 (3.31) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 24 (19.83) |

| Female | 97 (80.17) |

| Residence | |

| Rural | 61 (50.41) |

| Urban | 44 (36.36) |

| Non response | 16 (13.22) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 65 (53.72) |

| Single | 13 (10.72) |

| Separated | 15 (12.4) |

| Widow/Widower | 25 (20.66) |

| Non response | 3 (2.48) |

| Education Level | |

| Primary | 51 (42.15) |

| Secondary | 52 (42.98) |

| College/University | 7 (5.79) |

| No Education | 8 (6.61) |

| Non response | 3 (2.48) |

| Religion | |

| Christian | 113 (93.39) |

| Occupation | |

| Employed | 4 (3.31) |

| Business | 36 (29.75) |

| Farming | 76 (62.81) |

| Others | 2 (1.65) |

| Non response | 3 (2.48) |

| Where HIV test was done | |

| MCH | 41 (34.0%), |

| VCT | 30 (33.88%) |

| PITC | 29 (23.97%) |

| outreach clinics | 20 (16.53%) |

| Other places | 1 (0.83) |

| Reason for testing | |

| Pregnancy | 40 (33.06%) |

| Sickness | 30 (34.79%) |

| Partner tested positive | 24 (19.83%) |

| Employment | 4 (3.31%) |

| Wedding | 2 (1.65%) |

| Informed choice | 21 (17.36%) |

Table 1: Study participants’ socio-demographic characteristics.

Methods of linkage to HIV care

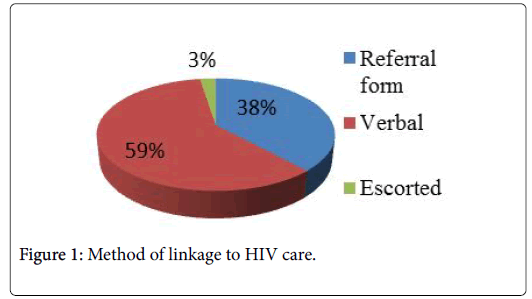

A majority of the patients 59% were linked to HIV care verbally, 38% who were given referral form to the next step of care while 3% of the study participants’ were escorted to the HIV care and treatment clinics Figure 1.

Factors associated with ART uptake among those on ART

As shown in Table 2, 65 (53.72%) of the study participants were on ART. Univariate analysis show that, female were more likely to uptake ART relative to males (uOR =0.64, 95% CI [0.26-1.60]). Those aged between 31-50 years (OR=0.97, 95% CI, [0.43-2.20]) and >51 years (OR=0.33, 95% CI [0.10-1.03]) were less likely to uptake ART relative to those aged between 25-30 years. Those from urban areas were less likely to uptake ART relative to those from rural areas (OR=0.64, 95%CI [0.26-1.60]).) Moreover, singles and widow/widower were less likely to uptake ART relative to the patients who are married (OR=0.50, 95% CI [0.16-1.70]), and (OR=087, 95% CI [0.35- 2.20]) respectively. In addition, participants who were separated were more likely to uptake ART (OR=1.21, 95% CI [0.39-2.20). Those with secondary education were more likely to uptake ART relative to those with primary education (OR=1.03, 95%CI [0.47-2.27]).

| Viral Load suppression n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | No | Yes | p value |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 8 (34.78) | 15 (65.22) | 0.686 |

| Female | 37 (39.36) | 57 (60.64) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| 25–30 | 13 (31.71) | 28 (68.29) | 0.315 |

| 31–50 | 22 (39.29) | 34 (60.71) | |

| >50 | 9 (52.94) | 8 (47.06) | |

| Residence | |||

| Rural | 23 (38.98) | 36 (61.02) | 0.928 |

| Urban | 16 (38.10) | 26 (61.90) | |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 23 (37.10) | 39 (62.90) | 0.747 |

| Single | 4 (33.33) | 8 (66.67) | |

| Separated | 5 (33.33) | 10 (66.67) | |

| Widow/Widower | 12 (48.00) | 13 (52.00) | |

| Education | |||

| Primary | 17 (33.33) | 34 (66.67) | 0.181 |

| Secondary | 18 (35.29) | 33 (64.71) | |

| College/University | 5 (71.43) | 2 (28.57) | |

| None | 3 (60.00) | 2 (40.00) | |

| Occupation | |||

| Employed | 1 (25.00) | 3 (75.00) | 0.6 |

| Business | 16 (45.71) | 19 (54.29) | |

| Farming | 25 (34.25) | 48 (65.75) | |

| Others | 1 (50.00) | 1 (50.00) | |

| Food by Prescription | |||

| Yes | 13 (65.00) | 7 (35.00) | 0.007 |

| No | 31 (32.63) | 64 (67.37) | |

| PSC Location | |||

| Yes | 40 (40.00) | 60 (60.00) | 0.401 |

| No | 4 (26.67) | 11 (73.33) | |

| Privacy | |||

| Yes | 36 (34.62) | 68 (65.38) | 0.021 |

| No | 8 (72.73) | 3 (27.27) | |

| Use Transport | |||

| Yes | 39 (36.79) | 67 (63.21) | 0.3 |

| No | 5 (55.56) | 4 (44.44) | |

| Chi-square test was used to determine whether there was association between the participant characteristics and viral load suppression | |||

Table 2: Association between the participant characteristics and viral load suppression.

In terms of source of income, those who were farmers, businessmen and doing others jobs were less likely to uptake ART (OR=0.43, 95% CI [0.04-4.37]), (OR=0.29, 95% CI [0.03-3.15]) and others (OR=0.33, 95% CI [0.01-11.94] ) respectively relative to those who were employed. Those who were not on food by prescription were more likely to uptake of ART relative to those who were not (OR=3.31, 95% CI [1.17-9.31]). Those who did not believe that transport was an important factor were more likely to uptake ART relative to those who considered it as a factor (OR=2.65, 95%CI[0.79-8.85])

Variables that were fit in the final adjusted multivariate logistic model were age, education, food by prescription, PSC location, and privacy. Our data reveal that participants aged between 31-50 years and ≥ 50 were less likely to uptake ART (aOR=0.97, 95% CI [0.43-2.20]) and (aOR=0.33, 95% CI [0.10-1.03]) respectively compared to those who aged between 25-30 years. In terms of education status, those with no education and college/university (aOR=0.24, 95% CI [0.02-2.47]) and (aOR=0.27, 95% CI [0.04-1.96]) respectively were less likely to uptake ART while those with secondary education who were more likely to uptake ART (aOR=0.935, 95% CI [0.44-2.49]) relative to those with primary education. Participants who had food by prescription were three times more likely to uptake of ART (aOR=2.97., 95% CI [0.88-10.05]). In addition those who did not consider PSC location as a factor were more likely to uptake ART (aOR=2.48, 95% CI [0.63-9.80]).

Influence of HIV Knowledge on continuum of care

As shown in Table 3, univariate analysis revealed that based on their universal knowledge of HIV knowledge females were less likely to uptake HIV continuum of care relative to males (OR=0.90, 95% CI [0.35-1.2.32]). Those aged 31-50 years were more likely uptake HIV continuum of care relative to those aged 25-30 years(OR=1.52, 95%CI[0.64-3.58)] Participants in the urban areas were more likely to uptake continuum of cares services relative to those from the rural areas (OR=1.00, 95%CI [0.43-2.34]). Respondents who were single were less likely to uptake HIV care continuum (OR= 0.50, 95% CI [0.15-1.70], as did the widow/widowers (OR = 0.87, 95% CI [0.35-2.20] compared to married participants. In contrast, those who were separated (OR=1.21, 95% CI (0.39-3.79) P=0.746) were more likely to uptake the HIV care continuum. For occupation, all variables used (business, farming and others as their sources) relative to employment had low odds of uptake of HIV continuum care (OR=0.29, 95% CI [0.03-3.1, (OR=0.43, 95% CI [0.04-4.37] and (OR=0.33, 95% CI [0.01-11.94] respectively. Variables that were fitted in the final adjusted multivariate logistic model were age, education, food by prescription, PSC location, privacy and transport. Our data revealed that patients aged between 31-50 years (OR=0.97, 95% CI [0.37-2.51]) and 51 years and above (OR = 0.34, 95% CI [0.09-1.21]), were less likely to uptake continuum of care relative to those who were between the ages of 25 and 30 years. In addition, it was found that those with college/ university education (OR=0.27, 95% CI [0.04-1.96]) and those with no education (OR=0.24, 95% CI [0.02-2.47],), were less likely to uptake continuum of care services relative to those having primary education. However, participants with secondary education were more likely to uptake continuum of care services relative to those with primary education (OR=1.05, 95% CI [0.44-2.49] (Table 4).

| Variable | ART uptake | uOR (95%CI) | p value | aOR (95%CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 15 (62.50) | ref. | 0.3326 | - | - |

| Female | 50 (51.55) | 0.64 (0.26-1.60) | - | - | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 25–30 | 24 (58.54) | ref. | 0.1015 | ref. | - |

| 31–50 | 33 (57.89) | 0.97 (0.43-2.20) | 0.949 | 0.97 (0.37-2.51) | 0.948 |

| >51 | 6 (31.58) | 0.33 (0.10-1.03) | 0.057 | 0.34 (0.09-1.21) | 0.094 |

| Residence | |||||

| Rural | 33 (54.10) | ref. | 0.8532 | - | - |

| Urban | 23 (52.27) | 0.93 (0.43-2.02) | - | - | - |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married | 36 (55.38) | ref. | 0.6696 | - | - |

| Single | 5 (38.46) | 0.50 (0.15-1.70) | 0.27 | - | - |

| Separated | 9 (60.00) | 1.21 (0.39-3.79) | 0.746 | - | - |

| Widow/Widower | 13 (52.00) | 0.87 (0.35-2.20) | 0.773 | - | - |

| Education | |||||

| Primary | 30 (58.82) | ref. | 0.0283 | ref. | - |

| Secondary | 31 (59.62) | 1.03 (0.47-2.27) | 0.935 | 1.05 (0.44-2.49) | 0.905 |

| College/University | 2 (28.57) | 0.28 (0.05-1.58) | 0.15 | 0.27 (0.04-1.96) | 0.195 |

| None | 1 (12.50) | 0.10 (0.01-0.87) | 0.037 | 0.24 (0.02-2.47) | 0.229 |

| Occupation | |||||

| Employed | 3 (75.00) | ref. | 0.6529 | - | - |

| Business | 17 (47.22) | 0.29 (0.03-3.15) | 0.314 | - | - |

| Farming | 43 (56.58) | 0.43 (0.04-4.37) | 0.479 | - | - |

| Others | 1 (50.00) | 0.33 (0.01-11.94) | 0.547 | - | - |

| Food by Presription | |||||

| Yes | 6 (30.00) | ref. | ref. | - | |

| No | 58 (58.59) | 3.31 (1.17-9.31) | 0.0185 | 2.97 (0.88-10.05) | 0.08 |

| PSC Location | |||||

| Yes | 53 (50.96) | ref. | 0.097 | ref. | - |

| No | 11 (73.33) | 2.65 (0.79-8.85) | 2.48 (0.63-9.80) | 0.194 | |

| Privacy | |||||

| Yes | 61 (57.01) | ref. | 0.0326 | ref. | - |

| No | 3 (25.00) | 0.25 (0.06-0.98) | 0.23 (0.05-1.03) | 0.194 | |

| Use Transport | |||||

| Yes | 60 (55.05) | ref. | 0.3613 | - | - |

| No | 4 (40.00) | 0.54 (0.15-2.04) | - | - | - |

Table 3: Factors associated with ART uptake.

| Variable | Universal Knowledge of HIV | uOR (95%CI) | p value | aOR (95%CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 8 (33.33) | Ref | 0.8209 | - | - |

| Female | 30 (30.93) | 0.90 (0.35-2.32) | - | - | - |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 25-30 | 12 (29.27) | ref. | - | - | |

| 31-50 | 22 (38.60) | 1.52 (0.64-3.58) | 0.3068 | - | - |

| >51 | 4 (21.05) | 0.64 (0.18-2.35) | - | - | |

| Residence | |||||

| Rural | 18 (29.51) | ref. | 0.9967 | - | - |

| Urban | 13 (29.55) | 1.00 (0.43-2.34) | - | - | - |

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married | 27 (41.54) | ref. | 0.0927 | ref. | |

| Single | 0 (0.00) | - | - | - | - |

| Separated | 2 (13.33) | 0.22 (0.05-1.04) | 0.056 | 0.22 (0.04-1.1) | 0.065 |

| Widow/Widower | 9 (36.00) | 0.79 (0.30-2.06) | 0.631 | 1.09 (0.35-3.41) | 0.885 |

| Education | |||||

| Primary | 11 (21.57) | ref. | 0.0464 | - | - |

| Secondary | 23 (44.23) | 2.88 (1.22-6.84) | 0.016 | 2.79 (1.11-7.04) | 0.03 |

| College/University | 2 (28.57) | 1.45 (0.25-8.54) | 0.678 | 0.89 (0.12-6.33) | 0.907 |

| None | 0 (0.00) | - | - | - | - |

| Occupation | |||||

| Employed | 1 (25.00) | ref. | 0.3918 | - | - |

| Business | 15 (41.67) | 2.14 (0.20-22.65) | 0.526 | - | - |

| Farming | 22 (28.95) | 1.22 (0.12-12.40) | 0.865 | - | - |

| Others | 0 (0.00) | - | - | - | - |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| CD4 Results | - | - | 0.456 | - | - |

| Waiting | 0 (0.00) | - | - | - | - |

| <500 | 14 (25.45) | - | - | - | - |

| 501-999 | 12 (35.29) | - | - | - | - |

| 1000-1499 | 12 (42.86) | - | - | - | - |

| Viral Load Results | |||||

| Suppressed | 24 (33.33) | ref. | 0.8103 | - | - |

| Not suppressed | 4 (28.57) | 0.80 (0.23-2.82) | 0.728 | - | - |

| No result | 6 (27.27) | 0.75 (0.26-2.16) | 0.594 | - | - |

| New | 4 (44.44) | 1.60 (0.39-6.51) | 0.511 | - | - |

Table 4: Influence of HIV knowledge of HIV on continuum of care.

Discussion

This study found that ART uptake stood at 53.72% which is similar to ART uptake reported in western Kenya [20], which is below the national ART coverage that stand at 78.5% [12]. This may be due to poor linkage on HIV care and management in this region which stands at 29.1% except for those tested at VCTs where the linkage is at 99.6% [22]. More importantly, this is still below the UNAIDS global target of 90% of HIV positive patients being initiated on ART by 2020 [20]. These data indicate that Kenya is yet to achieve these targets and there is a need to upscale linkage to HIV care for those who test HIV positive from all service areas.

Previously loss of patients along the HIV care continuum has been demonstrated [5] but less is known about the predictors of the uptake of the HIV care continuum among PLWHA in regions with high HIV burden. In this study a majority of the patients were linked to HIV care verbally or were given referral form to the next step of care with a few being escorted to the HIV care and treatment clinics. Consistent with previous studies, this study found that a majority of HIV patients on care were females [23,24]. Other studies in western Kenya have revealed that men are less likely to report for HIV testing, but even when they report and test positive they are less likely to enroll in HIV care [23]. Similarly a study in Uganda found that that male HIV testing rates and enrolment into care is comparatively lower relative females [24].

Although the high coverage of HIV testing and care has been attributed to integration of these services into the services provided in antenatal clinics, the low coverage among men has also been attributed to their health seeking behavior where they only attend hospital when they are severely ill [25]. In addition many facility-based testing initiatives are promoted through antenatal care PMTCT policy, although there is male involvement at the clinic it is difficult socially, or culturally to attract large numbers of men since in most cases men do not attend antenatal clinics [26]. Together, these data indicate the need of intervention strategies or programs targeting men in care in this setting

To achieve an efficient HIV care continuum there must be well organized special structures that ensure early diagnosis and initiation to treatment and care to achieve viral suppression [4,20]. However, studies have shown that in sub-Saharan Africa uptake of HIV continuum of care has been hampered by a multiplicity of factors at the individual, facility, community and structural levels [20,27]. The barriers include reluctance to go for HIV testing while healthy, unfavorable policies, stock out of supplies, stigma, distance to health facility, socioeconomic status, alternate healing systems and lack of psychosocial support [27]. Of significance a study in western Kenya revealed that the uptake of HIV services is largely influenced by individual perceptions of the importance of health care and knowledge [23].

This study revealed that age is an important determinant in ART uptake with those aged 25-30 years being more likely to uptake ART relative to those aged between 31-50 years and >51 years. This may be due to the fact that HIV testing uptake for both males and females in Kenya is highest between the ages of 25-29 years and mostly take place in VCT hence increased linkage to HIV care and management among this age group [28]. Of note are that these findings are in contrast with previous studies in indicating that found that young age is associated with low uptake of ART [29,30], suggesting that that there may be context-specific barriers to ART uptake that may persist despite changes to clinical guidelines encouraging early uptake.

The other barrier to ART uptake especially in rural setting in sub- Saharan Africa is distance from primary health care facilities due to transportation costs [31]. Consistent with this previous finding, this study also reveal that transport is an important determinant of ART uptake in our study population, suggesting that there is need of community based interventions that will increase ART coverage by making it available in community based healthcare facilities that are easily accessible to the PLWHIV. In deed previous findings also indicated that economic cost like transportation does not only lead to low HTC uptake but also ART uptake [4,15].

But this can be improved through up scaling of community-based HTC and ART services [18]. More importantly, this study also reveals that those who were on food by prescription were more likely to uptake of ART relative to those who were not. This is consistent with previous studies that have shown that nutritional interventions are not only important in management of HIV and AIDS but also improves patient’s general health together these data indicate that nutrition should be integrated with other HIV/AIDS programs with other livelihood programs especially in poor rural settings where food insecurity is common Several studies have revealed that lower education level is an important barrier to early initiation and retention in ART uptake among PLWHIV [20,24].

Similar to these finding this study revealed that individual with secondary education were more likely to uptake ART relative to those with no education or primary education suggesting that there is need for intervention strategies targeting those with lower education. The other hindrance to ART uptake is HIV related stigma. Indeed, HIV related stigma and discrimination have been identified as major barriers to uptake HIV related prevention services [12]. It adversely influences decisions to seek HIV testing In South Africa and Nigeria studies have shown that stigma is an important barrier to uptake of HIV testing and ART services.

Consistent with these findings this study also reports that patient’s privacy was an important determinant among HIV patients. This can lead patients to seek treatment in health facilities where they feel that they are not known and this may have a negative impact on ART uptake since economic cost including transportation may pose serious challenges to patients. Therefore, there is a need of intervention strategies geared towards reduction of stigma.

Conclusion

The main barriers to HIV care continuum in western Kenya include older age, transport cost, privacy, and male gender, lack of food supplement, correct accurate knowledge and stigma. Therefore, there is need to enhance the uptake of HIV care among PLWHA an interventions targeting multiple stage must be designed, which may improve linkages throughout the HIV care continuum in the short and long term. Strategies to improve Identification of the undiagnosed PLHIV and linking them to HIV care and management is a priority in order to achieve UNAIDS goal by 2020.

References

- Nakagawa, Lodwick RK, Smith CJ, Smith R, Cambiano V, et al. (2012) Projected life expectancy of people with HIV according to timing of diagnosis. AIDS.

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC (2011) Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 365: 493-505.

- Smith JA, Sharma M, Levin C, Baeten JM, van H, et al. (2015) Cost effectiveness of community based strategies to strengthen the continuum of HIV care in Rural South Africa: A health economic modelling analysis. Lancet 2: e159-e168.

- Kranzer K, Govindasamy D, Schaik NV, Thebus E, Davies N, et al. (2012) Incentivized recruitment of a population sample to a mobile HIV testing service increases the yield of newly diagnosed cases, including those in need of antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med 13: 132- 137.

- Rosen S, Fox MP (2011) Reteintion in HIV care between testing and treatment in Sub Saharan Africa: A systematic review. PLoS Med 8: e1001056.

- Lahuerta M, Lima J, Biribonwoha HN, Okamura M, Alvim MF, et al. (2012) Factors associated with late Antiretroviral therapy initiation among adult in Mozambique. PLoS ONE 7: e37125.

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC (2003) HIV testing attitudes, AIDS stigma, and voluntary HIV counselling and testing in a black township in Cape Town, South Africa. Sex Transm Infect 79: 442-447.

- Wachira J, Naanyu V, Genberg B, Koech B, Akinyi J, et al. (2014) Health facility barriers to HIV linkage and retention in Western Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res 14: 646.

- Musheke M, Ntalasha H, Gari S, McKenzie O, Bond V, et al. (2013) A systematic review of qualitative findings on factors enabling and deterring uptake of HIV testing in Sub-Saharan Africa. 13: 220.

- Tanser F, Bärnighausen T, Grapsa E, Zaidi J, Newell ML (2013) High coverage of ART associated with decline in risk of HIV acquisition in rural KwaZulu-NAtal, South Africa. Science 337: 966-971.

- Jain V, Byonanebye DM, Liegler T, Kwarisiima D, Chamie G, et al. (2014 ) Chages in population HIV RNA levels in Mbarara, Uganda, during scale-up of HIV antiretroviral therapy access. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 65: 327-332.

- Rooyen HV, Barnabas RV, Baeten JM, Phakathi Z, Joseph P, et al. (2013) High HIV testing uptake and linkage to care in a novel program of home-based HIV counselling and testing with facilitated referral in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 64: 1-8.

- Suthar AB, Ford N, Bachanas PJ, Wong VJ, Rajan JS, et al. (2013) Towards universal voluntary HIV testing and counselling: A systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based approaches. PLoS Med 10: e1001496.

- Lawn SD, Harries AD, Anglaret X, Myer L, Wood R (2008) Early mortality among adults accessing antiretroviral treatment programmes in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS 22: 1897-908.

- Genberg BL, Lee Y, Rogers WH, Wilson IB (2015) Four types of barriers to adherence of antiretroviral therapy are associated with decreased adherence over time. AIDS Behav 19: 85-92.

- Kigozi IM, Dobkin LM, Martin JN, Geng EH, Muyindike W, et al. (2009) Late-disease stage at presentation to an HIV clinic in the era of free antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 52: 280-289.

- NACC (2014) Kenya AIDS response progress report 2014, progress report towards to zero.

- Ackers ML, Hightower A, Obor D, Ofware P, Ngere L, et al. (2014) Health care utilization and access to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing and care and treatment services in a rural area with high HIV prevalence, nyanza province, Kenya, 2007. Am J Trop Med Hyg 90: 224-233.

- Chirawu P, Langhaug L, Mavhu W, Pascoe S, Dirawo J, et al. (2010) Acceptability and challenges of implementing voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) in rural Zimbabwe: Evidence from the Regai Dzive Shiri Project. AIDS Care 22: 81-88.

- Byamugisha R, Astrom AN, Ndeezi G, Karamagi CAS, Tylleskar T, et al. (2011) Male partner antenatal attendance and HIV testing in eastern Uganda: A randomized facility-based intervention trial. J Int AIDS Soc 14: 43.

- Layer EH, Kennedy CE, Beckham SW, Mbwambo JK, Likindikoki S, et al. (2014) Multi-level factors affecting entry into and engagement in the HIV continuum of care in iringa, Tanzania 9: e104961.

- Kazooba P, Kasamba I, Baisley K, Mayanja BN, Maher D (2012) Access to and uptake of ART in a developing country with high prevalence: A population based cohort study in rural Uganda 2004-2008. Trop Med Int Health 17: 49-57.

- Powers KA, Ghani AC, Miller WC, Hoffman IF, Pettifor AE, et al. (2011) The role of acute and early HIV infection in the spread of HIV and implications for transmission prevention strategies in Lilongwe, Malawi a modeling study. Lancet 378: 256-268.

- Cooke gs, Tanser FC, Barnighausen TW, Newell ML (2010) Population uptake of antiretroviral treatment through primary care in rural South Africa. BMC Public Health 10: 585.

- Kalichman SC, Cherry C, White D, Jones M, Kalichman MO, et al. (2012) Falling through the cracks: Unmet health service needs among people living with hiv in Atlanta, georgia. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 3: 244-254.

- Bolsewicz K, Debattista J, Vallely A, Whittaker A, Fitzgerald L (2015) Factors associated with antiretroviral treatment uptake and adherence: A review perspectives from Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom. AIDS care 27: 1429-1438.

- Yahaya LA, Jimoh AA, Balogun OR (2010) Factors hindering acceptance of HIV/AIDS voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) among youth in Kwara State, Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 14: 159-164.

- Yoliswa Y, Simbayi LC, Shisana O, Rehle T, Mabaso M, et al. (2014) Perceptions about the acceptability and prevalence of HIV testing and factors influencing them in different communities in South Africa. Sahara J 11: 138-147.

Citation: Ondimu TO, Mogaka RK, Asito AS, Ongwen S (2017) Factor Influencing HIV Care Continuum among People Living with HIV in Western Kenya. J Community Med Health Educ 7: 579. DOI: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000579

Copyright: ©2017 Ondimu TO, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 4687

- [From(publication date): 0-2017 - Apr 07, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 3831

- PDF downloads: 856