Eye Heroes: A Model of Raising Awareness about Eye Health by Training Children to Be Eye Health Champions

Received: 27-Nov-2018 / Accepted Date: 06-Dec-2018 / Published Date: 10-Dec-2018 DOI: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000639

Abstract

Objective: There is a lack of public awareness of the importance of regular eye tests to detect ocular and systemic conditions which may be asymptomatic. In many cases, timely intervention can prevent irreversible sight loss. In the absence of effective public health campaigns and screening programmes for all eye conditions except diabetic retinopathy, there is a need for awareness-raising about eye health. We report the impact of an initiative, Eye Heroes, which trains children in the UK to be community eye health champions.

Methods: Volunteers across the UK ran interactive workshops using Eye Heroes digital content to train school children aged 8-12 to become eye health champions. Children were taught about eye health and the importance of regular eye testing, and were encouraged to spread these messages amongst their communities. We collected impact data from a sample of 80 children across 3 UK sites (Oldham, Cardiff and Birmingham).

Results: Between November 2016 and November 2017, 200 volunteers delivered 119 workshops training 2,895 children to become eye health champions. 71 children from the sample of 80 (incomplete data from 9 children excluded) informed 601 people about eye health (median 6, IQR 3-10), resulting in 255 attendances for eye tests (median 2, IQR 0-6).

Conclusion: This study demonstrates that training children as eye health champions can translate into attendances for eye tests. Further evidence beyond this preliminary work is desirable to promote scaling up community-based interventions aimed at raising eye health awareness.

Keywords: Ophthalmology; Public health; Education; Community; Awareness

Introduction

Whilst there is no standard for vision screening in adults, a large proportion of sight loss could potentially be avoided if people attended regular eye testing with optometrists/eye health care professionals, allowing early detection of eye disease [1]. People having more regular eye examinations may be less likely to experience a decline in vision or functional status [2]. However, most members of the general public are unaware of the importance of regular eye testing [3]. Improving public understanding about the role of eye tests in preventing sight loss, and not just to determine the need for spectacles, should be an important public health message [4-7]. In England, preventable sight loss is an indicator in the Public Health Outcomes Framework 2016-2019 [8].

Preventable sight loss is a major public health concern in the UK and is projected to rise steeply in the future [9]. Inequalities in the uptake of National Health Service-funded sight tests exist in at-risk groups including ethnic minority communities, those in lower socioeconomic groups and older people [4,7,10-14]. People may not attend for eye tests due to language barriers, social isolation, socioeconomic deprivation, perceived costs, inertia, learning disabilities and the anxiety provoked by the stigma of impaired eye health [5,6,11,15,16]. The poor uptake of regular eye tests is a major contributor to avoidable sight loss, especially amongst hard-to-reach communities with lower risk perceptions, known to be harder to reach with traditional public health campaigns [17,18].

Sight loss costs the UK economy an estimated £15-28 billion annually, yet only around £2 million is spent on prevention and awareness [19]. Preventable sight loss is an increasing problem and the need for effective prevention is pressing. Previous eye health campaigns have failed to demonstrate lasting impact on general eye health awareness or altered health-seeking behaviour in vulnerable groups including older people and migrant ethnic communities [20]. When surveyed, most people can only recall optician advertisements as a source of information about eye health [21]. If advertisements are the sole source of information for many, this marks eye health as distinct compared to all other forms of primary healthcare prevention.

We have developed a volunteer-led, low-cost intervention (“Eye Heroes”) to raise awareness about eye health. Children aged 8-12 are trained through short, interactive volunteer-led workshops in schools to become champions of eye health to inform people in their communities about the importance of regular eye tests (www.eyeheroes.org.uk). Children are enthusiastic and open to learning, making them potentially powerful health advocates. Each child has a unique reach into their own community and can overcome barriers that can impair traditional awareness-raising campaigns, including language, lower socioeconomic status, misunderstandings and fear. By harnessing the reach of children, Eye Heroes hopes to influence people that might otherwise be hard-to-reach, while educating future generations about eye health.

The present report aimed to quantify the number of children reached by Eye Heroes workshops held between November 2016 to November 2017, to estimate the number of contacts each child informs about eye health and the number of subsequent eye test attendances. We also aimed to collate feedback from volunteers, participating children and teachers and draw out lessons and recommendations for improvements.

Methodology

Eye Heroes workshops

Eye Heroes workshops were delivered in schools to children aged 8-12 years across 18 regions in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Workshops were delivered by volunteers who expressed interest via www.eyeheroes.org.uk. All volunteers received matched web-based training using www.eyeheroes.org.uk/resources with ready access to a volunteer coordinator by email, following protocols currently used by the Eye Heroes programme. Between 2016 and 2017 Eye Heroes recruited medical students, optometrists, orthoptists, teachers and parents as volunteers. These volunteers accessed the website or emailed Eye Heroes directly after reading about the initiative in online and print publications, seeing posts on social media or interacting with the Eye Heroes team at UK ophthalmic and public health events. After signing an agreement with Eye Heroes, all volunteers gained individual access to password-protected workshop material and guidance online, along with the workshop presentation file with embedded videos. All volunteers approached local schools individually to organize workshops.

An Eye Heroes workshop lasts approximately 50-60 minutes and consists of:

• Introduction to the eye and vision with a short video (3 minutes).

• Animation 1. Scene-setting about the problem of avoidable sight loss in the UK (2 minutes).

• Other activities lasting 10 minutes each from a choice including a picture quiz, ‘spot the difference’ game, guessing the contents in a cardboard box by feel, looking at pupillary reflexes, a guided obstacle course and labeling a basic eye diagram.

• Video about eye tests (5 minutes).

• Video highlighting that many people do not attend for regular eye tests (2 minutes)

• Animation 2. An Eye Hero discussing the importance of eye health with an adult (2 minutes).

• Role play. Children practice conversations to convey the key messages learnt (10 minutes).

• Conclusion. Recap of key messages and issuing of certificates to new Eye Heroes (5 minutes).

Before running workshops, volunteers were issued with information about eye health, information to be disseminated to schools, certificates to be given to participating children and parental consent forms to be signed in advance of workshops when volunteers wished to take pictures and record videos. Where required by schools, an up-todate disclosure and barring service check was verified.

Data collection

We collected information about the number of children who attended the workshops from the volunteers running the workshops. To measure the number of eye tests initiated by children’s attendance at Eye Heroes workshops, we had devised and previously piloted three data collection methods:

1) We gave children pre-stamped/freepost postcards to pass on to friends and family, who would then give them to their optometrist when attending for an eye test. The optometrists were asked to mail them back to the central Eye Heroes team to document eye test attendances.

2) We gave Eye Heroes-branded wristbands to local optometrists, asking them to give wristbands to clients who presented because of an Eye Heroes workshop, with or without a freepost postcard, and counted the number of remaining wristbands at the end of the sixweek period following a local Eye Heroes workshop.

3) We gave Eye Heroes-branded stickers to teachers at participating schools who gave children stickers as a reward for each person who attended an eye test after the child told them about what they had learned at the workshop. The sticker activity was designed to be simple and fun, whilst capturing data about the number of people informed about eye health per child, categories of people informed, the number of people attending for eye tests and the locations of eye tests. These questions were formulated to allow the evaluator to check for completion error and to identify inaccurate information. For example, if a child reported that they had informed 6 people, but could only name 2, then reported that 10 had attended eye tests, without giving locations, their report was assumed to be inaccurate. These data were excluded from analysis. In an attempt to reduce bias, teachers were specifically asked to provide stickers even if children reported telling no one about eye health to avoid the incentive to fabricate results.

The methods pilot (data not shown) indicated a loss of engagement from optometrists over time. For the present report, we therefore used method 3, the sticker activity, as the primary source of evidence.

Eye Heroes-branded stickers were issued to teachers at 3 participating schools in the sample areas of Cardiff, Birmingham and Oldham, selected based on diversity using data from the Royal National Institute for the Blind sight loss data tool [22] (Table 1). These regions contain individuals which may be harder to reach with conventional campaigns due to factors including language barriers and lower socioeconomic status. Time and budgetary constraints precluded data gathering from all children trained as eye health champions in the United Kingdom over the 12 month study period. Data were therefore collected from a sample of 80 children at the participating schools. As we intended to carry out a descriptive analysis, we did not perform a sample size calculation. The sample was probabilistic and chosen to include children from different regions within the United Kingdom with diversity in terms of the level of urbanisation, the proportion of minority ethnic groups and the percentage of unemployment. We did not plan to detect specific eye conditions, and did not plan to monitor specific diagnostic outcomes downstream of the school workshops, and therefore did not take prevalences into consideration.

| Area | Urbanisation | Population | % age ≥ 65 | % non-White | % unemployed | Sight impaired |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiff | Mostly urban | 357,160 | 14 | 15 | 6 | 585/100,000 |

| Birmingham | Urban major conurbation | 1,124,569 | 13 | 42 | 10 | 709/100,000 |

| Oldham | Urban major conurbation | 230,823 | 16 | 23 | 8 | 625/100,000 |

Table 1: Sample area data from the Royal National Institute for the Blind sight loss data tool.

We also collected feedback from volunteers and children participating in workshops.

The volunteers asked children the following questions:

• How was the workshop?

• What did you learn today?

• What are you going to do after the workshop?

Feedback was collected from volunteers via a standardised online form which all volunteers were asked to complete prior to receipt of certificates.

Data analysis

A member of the study team not involved in delivering the workshops (ARB) collected data using Microsoft Excel. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (IBM Corp).

Results

Numbers of children and contacts

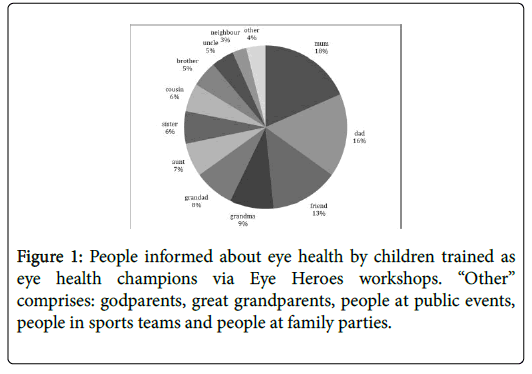

Between November 2016 and November 2017, 200 volunteers were recruited to deliver 119 Eye Heroes workshops, and 2,895 children were trained as eye health champions. From a sample of 80 children from schools in Birmingham, Cardiff and Oldham, data from 9 children were incomplete and therefore excluded from analysis. 71 children informed 601 people about eye health (median 6, IQR 3-10, range 0-86), resulting in 255 attendances for eye tests (median 2, IQR 0-6). The categories of people informed included family members, friends, neighbours, people at public events, people in sports teams and people at family parties (Figure 1).

Feedback from volunteers and participating children

61/65 (93.8%) of volunteers responded that they would run workshops in the future with the remaining 4/65 (6.2%) responding that they might run workshops in the future (Table 2). Many comments related to workshop delivery and their perceived effectiveness:

| Question | Respondents (n) | Feedback |

|---|---|---|

| How engaged were the children who attended the workshop? | 65 | 65/65 reported that children were very engaged. |

| How many children responded positively to the question? “How was this workshop?” | 65 | 65/65 responded that all children in each class responded positively. |

| What did children say they would do after the workshop? | 65 | 61/65 (93.8%) of volunteers reported that children said they would inform others about eye tests. |

| 1/65 (1.5%) reported that children said they would play the Eye Heroes online game after the workshop. | ||

| 3/65 (4.6%) responses were nonsensical. | ||

| Did the school share any feedback? | 60 | All qualitative feedback shared was positive e.g. “informative”, “interactive”, “engaging”. |

| How easy was it to use the resources? | 65 | 45/65 (69.2%) rated ease of use as “very easy”. |

| 14/65 (21.5%) rated ease of use as “easy”. | ||

| 5/65 (7.7%) responded neutrally (neither difficult nor easy). | ||

| 1/65 (1.5%) responded that the resources were “difficult” to use. | ||

| Did you contact the school or after-school club to arrange the workshop yourself? | 65 | 65/65 volunteers organised workshops themselves (i.e. without the need for additional help from the Eye Heroes team). |

| Would you consider running another workshop in the future? | 65 | 61/65 (93.8%) responded “yes”, 4/65 (6.2%) responded “maybe”. |

Table 2: Eye Heroes volunteer questionnaire responses.

• On the subject of workshop materials “great, straightforward and easy to follow” (volunteer via feedback form)

• “The template programme created by Eye Heroes is an accessible and repeatable tool that enables volunteers to carry out these sessions in the local community that deliver important messages regarding eye health to young impressionable minds” (volunteer via feedback form)

• “The children were really engaged. They all seemed to really enjoy the workshop and actually got really into it” (volunteer via feedback form)

• “The activities were appropriately pitched to the children’s age and interest, and also informed them of the importance of eye care and what they-as individuals-can do” (teacher via feedback form)

• “Lots of them (children) said that they would go away and talk to their families about it” (teacher via feedback form)

• “Eye Heroes is a fantastic programme, it allows children to learn really useful knowledge not covered in the curriculum” (teacher via feedback form)

• “I enjoyed it because they told us lots of reasons why we should get an eye test and how important it is” (child after an Eye Heroes workshop)

• “People should not assume that going for an eye test is painful or expensive” (child after an Eye Heroes workshop)

Discussion

Eye Heroes is the first child-delivered intervention to inform communities about eye health and the benefits of regular eye tests. We have shown that adults attended for eye tests following Eye Heroes workshops (Figure 1). 71 children from our sample informed 601 people about eye health which initiated 255 attendances for eye tests. Feedback from volunteers running the workshops indicates that the online material is easy to use (Table 2).

Our evaluation has several limitations. We were unable to establish a robust system to quantify the increase in eye test appointments triggered by Eye Heroes workshops. It was not always possible to set schools and local optometry practices up to participate in data collection following workshops. We also have no data about longerterm knowledge retention in the children who took part in the workshops, or about habit-forming with regards to regular eye testing.

Our findings on the effectiveness of the Eye Heroes communitybased intervention are similar to those of previous campaigns which engaged children as instigators of health behavior change including a national anti-smoking campaign [23] and the Child to Child Trust [24]. Web-based materials for educating children about health have also been used successfully to raise awareness about oral health [25]. An improvement in student eye health literacy has been reported following eye health promotion in schools [26].

The Eye Heroes concept follows the principles of human-centred design, defined as a creative approach to problem-solving, producing new solutions best able to meet the needs of the target audience [27]. Key strengths of this approach include the fact that children can act as community champions [17,21], and that health awareness is raised in the community whilst workshops directly educate a future generation and promote enhanced eye health literacy. In addition, positive habit established from an early age is a known enabler to accessing primary eye care services [21]. In contrast to existing advertising campaigns, Eye Heroes does not have a commercial interest and is not associated with notions of cost and retail. Lastly, important aspects of community-based interventions are scalability and sustainability. Engaging young people helps to build longevity and broader conversations about eye health within families and communities [21].

In conclusion, the Eye Heroes campaign may be an effective way to deliver information about eye health to hard-to-reach communities. A cluster-randomized controlled trial could formally quantify its efficacy and enable its further development.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Moorfields Biomedical Research Centre. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Eye Heroes was supported by a grant from Moorfields Eye Charity.

References

- Shickle D (2015) What proportion of sight loss is preventable? The need for a confidential enquiry for the eye care pathway. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 35: 591–594.

- Sloan FA, Picone G, Brown DS, Lee PP (2005) Longitudinal analysis of the relationship between regular eye examinations and changes in visual and functional status. J Am Geriatr Soc 53: 1867-1874.

- McLaughlan B, Edwards A (2010) Understanding of the purpose of an eye test among people aged 60 and over in the UK. Optom Pr 11: 179-188.

- Van Der Pols JC, Thompson JR, Bates CJ, Finch S (1999) Is the frequency of having an eye test associated with socioeconomic factors? A national cross sectional study in British elderly. J Epidemiol Community Health 53: 737-738.

- Shickle D, Griffin M (2014) Why don’t older adults in England go to have their eyes examined? Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 34: 38-45.

- Shickle D, Griffin M, Evans R, Brown B, Haseeb A, et al. (2014) Why don’t younger adults in England go to have their eyes examined? Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 34: 30-37.

- Leamon S, Hayden C, Lee H, Trudinger D, Appelbee E, et al. (2014) Improving access to optometry services for people at risk of preventable sight loss: A qualitative study in five UK locations. J Public Heal 36: 667-673.

- Department of Health (2016) Improving outcomes and supporting transparency. Part 2: Summary technical specifications of public health indicators. London.

- Access Economics (2009) Future sight loss UK: The economic impact of partial sight and blindness in the UK adult population. RNIB.

- Awobem JF, Cassels-Brown A, Buchan JC, Hughes KA (2009) Exploring glaucoma awareness and the utilization of primary eye care services: Community perceived barriers among elderly African Caribbeans in Chapeltown, Leeds. Eye 23: 243.

- Patel D, Baker H, Murdoch I (2006) Barriers to uptake of eye care services by the Indian population living in Ealing, west London. Health Educ J 65: 267-276.

- Wormald RP, Basauri E, Wright LA, Evans JR (1994) The African Caribbean eye survey: Risk factors for glaucoma in a sample of African Caribbean people living in London. Eye (Lond) 8: 315–320.

- Rahi JS, Peckham CS, Cumberland PM (2008) Visual impairment due to undiagnosed refractive error in working age adults in Britain. Br J Ophthalmol 92: 1190-1194.

- Shweikh Y, Ko F, Chan MPY, Patel PJ, Muthy Z, et al. (2015) Measures of socioeconomic status and self-reported glaucoma in the UK Biobank cohort. Eye 29: 1360-137.

- Shickle D, Farragher TM (2015) Geographical inequalities in uptake of NHS-funded eye examinations: Small area analysis of Leeds, UK. J Public Heal 37: 337-345.

- Dandona R, Dandona L (2001) Socioeconomic status and blindness. Br J Ophthalmol 85:1484-1488.

- Johnson (2011) A review of evidence to evaluate effectiveness of intervention strategies to address inequalities in eye health care. UK: RNIB.

- Shickle D, Todkill D, Chisholm C, Rughani S, Griffin M, et al. (2015) Addressing inequalities in eye health with subsidies and increased fees for general ophthalmic services in socio-economically deprived communities: A sensitivity analysis. Public Health 129: 131-137.

- Pezzullo L, Streatfeild J, Simkiss P, Shickle D (2018) The economic impact of sight loss and blindness in the UK adult population. BMC Health Serv Res 18: 63.

- Baker H, Murdoch IE (2008) Can a public health intervention improve awareness and health-seeking behaviour for glaucoma? Br J Ophthalmol 92: 1671-1675.

- Carol H (2012) The barriers and enablers that affect access to primary and secondary eye care services across England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. A report to RNIB by Shared Intelligence.

- Child to Child Trust (2017) We believe that when children work together, they can change their world.

- Paudel P, Yen PT, Kovai V, Naduvilath T, Ho SM, et al. (2017) Effect of school eye health promotion on children’s eye health literacy in Vietnam. Health Promot Int.

Citation: Shweikh Y, Rathee M, Barber AR, Dahlmann-Noor A (2018) Eye Heroes: A Model of Raising Awareness about Eye Health by Training Children to Be Eye Health Champions. J Community Med Health Educ 8: 639. DOI: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000639

Copyright: © 2018 Shweikh Y, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 3652

- [From(publication date): 0-2018 - Apr 07, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 2899

- PDF downloads: 753