Extending Mentoring in Palliative Medicine-Systematic Review on Peer, Near-Peer and Group Mentoring in General Medicine

Received: 18-Oct-2017 / Accepted Date: 02-Nov-2017 / Published Date: 07-Nov-2017 DOI: 10.4172/2165-7386.1000323

Abstract

A shortage of trained mentors in Palliative Medicine has inspired efforts to employ near peer, peer and group (NPG) mentoring to supplement traditional novice mentoring or mentoring between senior clinicians and junior doctors and or medical students as a means of ensuring that holistic support is available to mentees in a timely, appropriate and personalised manner. Scrutiny of prevailing data on NPG mentoring however, reveals significant gaps in understanding and practice of NPG mentoring that has precipitated conflation with preceptorship, rolemodeling, sponsorship, supervision and counseling. A failure to consider mentoring's evolving, goal-sensitive, context-specific and relational, mentee, mentor and organizational-dependent process nature has further limited available NPG mentoring research. This review seeks to advance a clinically-relevant understanding of NPG mentoring that will help delineate the practice of NPG mentoring and potentially see it blended with novice mentoring.

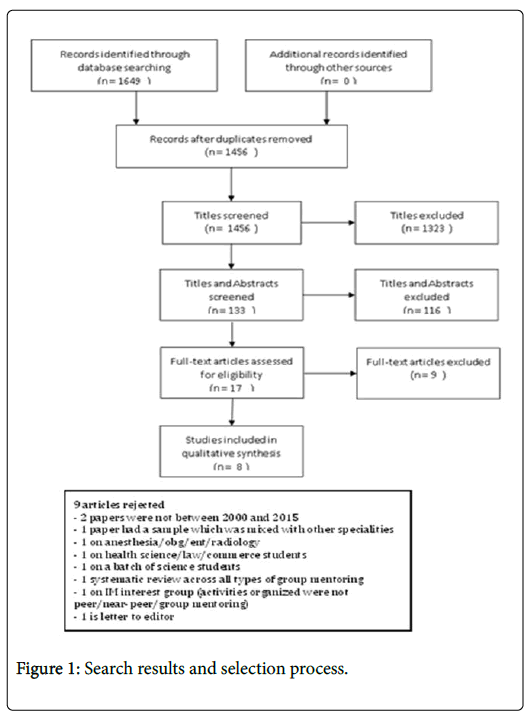

Methods: The literature search on NPG mentoring in internal medicine was performed on publications across Embase, PsycINFO, ERIC, PubMed, Medline and Scopus databases for articles published between January 2000 to December 2015. The BEME guide and STORIES statement were used to develop a narrative.

Results: 1456 citations were reviewed, 8 full text of articles were included and 4 themes were identified through thematic analysis including definitions and descriptions, the structure, the benefits and the obstacles to NPG mentoring.

Conclusions: These themes allow for the first evidenced based definition of NPG mentoring. In proffering a means to blending NPG mentoring with novice mentoring, the data suggests the need for effective mentor and mentee training and a flexible structure to the mentoring process that will cater for changes in the evolving relationships but allow effective oversight of the process. Key to this blending process is also maintenance of a social and friendly atmosphere underlining the importance of mentoring environments and highlighting areas for future research.

Keywords: Near-peer mentoring; Peer monitoring; Group monitoring; Systemic review

Introduction

Mentoring improves the professional and personal development of mentees and mentors, enhances the reputation of host organizations and improves overall patient experience [1-6]. Realizing these benefits pivot upon the provision of consistent, timely, appropriate, personalised and holistic support of mentees by trained mentors in structured and regulated mentoring programs [1-6]. In Palliative Medicine (PM) mentoring is also seen as a means of providing holistic support to mentees [4,5].

A shortage of trained mentors in PM however, has inspired efforts to employ near peer, peer and group (NPG) mentoring to supplement traditional novice mentoring or mentoring between senior clinicians and junior doctors and or medical students as a means of ensuring that holistic support is available to mentees in a timely, appropriate and personalised manner [7-16]. However, efforts to blend the two approaches have been fraught. Scrutiny of articles on NPG mentoring reveals a lack clear definitions, diverse practices and poor oversight of mentoring processes [7-16].

Whilst a systematic review of NPG mentoring in medicine is called for to address these gaps, it is evident that such efforts must account for two critical elements of mentoring [1-6,15-17]. First the lack of a common understanding of mentoring [1-6,15-17]. This has seen the inaccurate blending of different and ultimately distinct forms of mentoring and conflation with practices such as preceptorship, rolemodeling, sponsorship, supervision and counseling [1-6,15-17]. This complicates efforts to effectively study and characterize these forms of mentoring [1-6,15-17].

Rather than falling for the same pitfalls, melding of peer, near peer and group mentoring under the aegis of NPG mentoring acknowledges that differentiation between near and peer mentoring can be fraught and may not be clearly demarcated in prevailing journals. Intermingling peer and near peer mentoring with group mentoring raises questions as to the distinctions made in classifying a mentee, a near peer and a mentor and if this triad would be considered a mentoring group. Prevailing literature remains ambiguous on this matter, limiting meaningful distinction between the three mentoring approaches and validating the melding of the approaches.

Second, effective scrutiny of NPG mentoring must account for mentoring’s nature [1-6,15-17]. Recent studies have characterized mentoring as an evolving, goal-sensitive, context-specific and relational, mentee, mentor and organizational-dependent process [1-6,15-17]. This suggests that mentoring relationships between mentors and mentees and potentially amongst peers and near peers evolve over time as the relationships matures and as the mentoring relationships traverse different situations, evolving mentee needs, motivations and goals and mentor availability over the course of the mentoring program [1-6,15-17]. Mentoring reviews have also shown that mentoring processes are also dependent upon the support of their host organizations for administrative and financial support and in nurturing a mentoring culture within the organization [1-6,15-17]. Host organizations are also seen to play a key role in creating a conducive mentoring environment that nurtures individual mentoring relationships within a mentoring program [1-6,15-17]. Of particular relevance to a review of NPG mentoring is that mentoring’s nature limits comparisons of mentoring practice across different specialties, clinical contexts, mentee groups and differing healthcare and education systems [1-6,15-17]. Such obstacles affect study of mentoring and raise concerns about the consistency, transparency and efficacy of mentoring approaches employed in prevailing mentoring programs [1-6].

Addressing these concerns underscores present efforts to scrutinize NPG mentoring practices and advance a clinically-relevant understanding of NPG mentoring that can forward a flexible, adaptive and responsive concept of mentoring that will contend with inherent differences in health and educational systems, accommodate for the evolving nature of mentoring relationships and address the potential shortfall in mentoring support.

Search strategy

Three authors carried out independent literature searches of Embase, PsycINFO, ERIC, PubMed, Medline and Scopus databases articles on peer, near-peer and or group mentoring published in English or had English translations between 1st January 2000 and 31st December 2015. The search terms used include Peer, Near-peer, Group, AND Mentoring, Mentorship, Mentor or Mentees, AND General or Internal Medicine.

We confined our attention to NPG mentoring in Internal Medicine in recognition of the differences in mentoring practice across the different specialities [1-6,15-17]. We further limited our attention to studies of mentoring published after 2000 given a dearth of relevant studies of mentoring prior to 2000 and suggestions that articles on mentoring in general prior to 2000 tended to conflate mentoring with other practices [1-6].

We included NPG mentoring in Clinical or Academia or Research, Internal Medicine or General Medicine as well as facilitated peer mentoring and combinations of novice and group or peer and or near peer mentoring. We also included all forms mentoring reports, editorials and perspective papers on peer, near-peer and group mentoring. Inclusion of perspectives papers provided long term data on mentoring outcomes [2].

To focus this review, we employ the World Health Organisation’s definition of Internal Medicine to exclude surgical specialties, Pediatrics, Emergency Medicine, Obstetrics and Gynecology and Clinical and Translational Science [18]. Also excluded were Interdisciplinary mentoring, supervision, preceptorship, coaching, advising, role-modeling, sponsorship, counseling and patient, family, youth and leadership mentoring. Each author used End Note to remove duplicates and compile and consolidate a list of titles to be included. These lists were discussed amongst all the authors and Sambunjak et al. “negotiated consensual validation” was employed to forward a final list of articles to be reviewed [19]. Two authors independently reviewed the shortlisted abstracts and employed “negotiated consensual validation” to forward a list of articles to be included in this review [19]. The inclusion and exclusion factors are presented as part of the PICOS (Table 1).

| PICOS | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Peer or Near Peer or Group Mentoring Program (clinical/academia/research) limited to Internal Medicine (WHO Definition) | Other allied health professionals |

| Mentorship in surgery, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology | ||

| Wet bench/lab work | ||

| Veterinary | ||

| Dentistry | ||

| Psychology | ||

| Coaching | ||

| Advisorship supervision | ||

| Preceptorship | ||

| Intervention | Mentoring by peer/near-peer/senior | Dyadic Mentoring |

| Group mentoring | One-to-one mentoring | |

| Comparison | Definition and Description of peer, near peer and group mentoring | - |

| Nature of peer, near peer and group mentoring | ||

| Structure of peer, near peer and group mentoring | ||

| Benefits of peer, near peer and group mentoring | ||

| Outcome | Knowledge on success factors and its barriers to successful mentorship can be used to further develop peer/near-peer mentorship programmes | - |

| Study design | All study designs are included | No article is excluded based on study design |

| - Descriptive papers | ||

| - Qualitative, quantitative and mixed study methods | ||

| - Perspectives, opinion, commentary pieces and editorials |

Table 1: Inclusion and exclusion factors-PICOS.

Quality assessment of studies

A quality assessment of all included papers was done using the BEME guidelines [20] and the Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer Manual 2014 Version 2 (JBI) [21]. The JBI model of meta-synthesis was adopted because of its ease of use, the lack of need to reinterpret the meaning of the original data and as a record for future studies (Appendix 1-4) [21].

Data extraction and analysis

In the absence of an A. priori framework for mentoring and in keeping with recent evidence of the effectiveness of thematic analysis in circumnavigating the limitations posed by mentoring’s nature, the authors adopted Braun and Clarke’s approach to independently carry out thematic analyses of included articles [1-6,22]. The authors used Best Evidence Medical Education (BEME) Collaboration guide and the STORIES (Structured Approach to the Reporting In Healthcare Education of Evidence Synthesis) statement as a guide to develop a narrative from the included articles given the presence of a wide range of research methodologies amongst the included articles that made it difficult to perform statistical pooling and analysis [23].

A template and framework for coding was constructed using “negotiated consensual validation” [21] approach during the first round of coding. Subsequently, each member of the team coded all the papers [22]. Codes were constructed from the ‘surface’ meaning of the data [22]. Semantic themes were identified from ‘detail rich’ codes focused upon the various aspects of the mentoring process [22]. The authors grouped the codes, identified themes across the different mentoring programmes and created individual lists of themes. All the authors participated in online and face-to-face discussions and used “negotiated consensual validation” to forward a unanimously determined list of themes [22].

Results

A total of 1456 citations were reviewed, 133 full text articles were retrieved and 8 were included (Figure 1). Three of the 8 articles described facilitated peer group mentoring programmes to improve research skills amongst middle grade female physicians [9-11], 1 article detailed a different peer group research mentoring programme for junior faculty (IMeRGE) [12] and 1 article described a one-to-one near-peer mentoring between first and second year residents aimed at helping residents complete the ‘core’ medical training of Residency [13]. The three remaining accounts of NPG mentoring experiences [14-16]. Thematic analysis of the 8 papers yielded 4 themes including definitions and descriptions, the structure, the benefits and the obstacles to NPG mentoring. We discuss each theme in turn.

Definitions and descriptions of peer, near-peer and group mentoring

Thematic analysis of definitions and descriptions of mentoring forwarded by the 8 paper revealed 5 sub-themes that help characterize the participants, the goals, the nature of interactions, the approach and the outcomes of NPG mentoring.

Participants in NPG mentoring are of similar rank [7-13], age and experience [7,10,11] and often at the same stages of their personal, family and professional lives. They share common interests [8-10,12,13], values and goals [8-10,12,14].

The goals that drive participation in NPG mentoring are primarily academic advancement [7,9,10,13]. For some it is a means of addressing gender and ethnic disparities [7,9,13] in access to mentors whilst for others it is a means of accessing help and support to meet career obstacles and academic requirements.

The nature of interactions in NPG mentoring is collaborative [7-9,13,14] and voluntary [7-9,11,13]. The social ‘feel’ to interactions that often take place outside the work environment helps build personal ties, lay the foundations for honest and personal feedback, sharing of personal issues and providing individualized support.

The practice builds on the diversity of the group [7,14] of between 3 to 5 peers and the various skills and experiences each member brings. The social environment that it is built in allows for a nurturing environment but also the need for some agreement upon roles, rules and responsibilities. In some cases NPG mentoring sees the inclusion often by invitation of a facilitator to help guide the project.

For many NPG mentoring builds lasting collaborations and friendships [10-12,14].

The structure of NPG mentoring

The 19 subthemes identified under this theme provide a sketch of the common aspects of NPG mentoring. Central to a NPG mentoring approach is a blend of informal interactions within a structured process. Use of a structured mentoring framework [7-11] establishes clear outcomes and roles and responsibilities for the various members of the team and also allows the inclusion of senior clinicians as facilitators who guide and oversee the interactions between the peers. Facilitators chosen to lead the group of between three and five peers often share common goals and interests with the group and improve peer group discussions through facilitations of discussions and sharing their experiences [9,11,12].

A structured process also provides the template for pre-mentoring meetings [7-9,11], mentor and mentee training, the duration of the project, the frequency and form of meetings [9,11] and signed agreements [7-9,11] between all the members of the group to ensure a basic code of conduct is maintained. Interactions in NPG mentoring often use of a blend of email, phone and text messaging to support face-to-face discussions and facilitate timely feedback [7-9,11].

NPG mentoring’s use of informal environment facilitates more flexible and convenient meetings amongst peers whilst the social atmosphere nurtures more personal ties amongst peers. This builds a sense of connectedness within the group that provides more personalised feedback. Informality within the mentoring process also nurtures collaborative partnerships and ‘longer lasting’ more personal ties [9]. In some cases, collaborations continued beyond the duration of the program with many peers reporting a readiness to mentor in future programs [9,11].

Overcoming time, funding and administrative pressures however, requires formal support from a host organization. This allows better recruitment and oversight of the process and the nurturing of the mentoring process. It is here that the need for structure within the NPG mentoring process becomes clearer.

The benefits of peer, near peer and group mentoring

The potential for enduring collaborations and friendships are amongst the primary benefits of NPG mentoring [12,14,15]. Other benefits include addressing a shortage of mentors [11,16], overcoming disparities in access to mentors amongst females and mentees from ethnic minorities [10,11], improving networking opportunities [15], enhancing academic advancement [10-13,15,16] and improving research skills [10-14,16] In addition, NPG mentoring protects against abuse of power that can happen in traditional dyadic mentoring relationships [16], provide better work life balance whilst still meeting career and academic requirements [9,11], empowering mentees [16] and improving collaborative working [10,16] and leadership skills [16]. An overview of the Organizational aspects and outcomes of the various mentoring programs described are presented in the table below (Table 2).

| Background | Organizational Aspects | Outcomes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Type of Mentoring | Formation of groups | Factors considered | Written Agreement | Frequency and Duration | Meeting Modality | Primary Outcomes of Mentoring achieved by participants | Secondary Outcomes of Mentoring achieved by participants |

| Files et al. [7], Mayer et al. [8], Varkey et al. [9], Mayer et al. [13] | Peer group research mentoring amongst female faculty | Assigned by organizers of mentoring program | Participants self-identified peers they wished to potentially work with in group setting Research and Clinical Interest based on CV and individual’s scholarly interests | Good Faith Agreement where members agree to participate actively and remain engaged throughout the program | 1 Year, Every 4-6 weeks | In person, Phone Conferences, Email | Development in research skills: -literature searches -reference management -paper writing -critical evaluation of literature -grant application -submission for conference abstract -submission of the papers for publication -oral presentations |

Teamwork, Avenue for socialization, Peer support for both work related issues and life challenges Some participants remained in the same group to pursue further projects even after completion of program |

| Bussey-Jones et al. [10] | Peer group research mentoring in junior faculty | Only 1 mentoring group was formed, participants had a desire to work with one another in development of research and other academic skills for career advancements | No Agreement; but ground rules were agreed upon to ensure accountability of all members where failure of adherence could potentially lead to expulsion | Not specified, Every week | In person | Greater confidence in networking and collaborative group projects | Avenue for socialization, Peer support for both work related issues and life challenges | |

| Webb et al. [11] | Near Peer mentoring for core medical training between year 2 and year 1 Residents | Assigned by organizers of mentoring program | Personal Statement, Career Plans, and Interests and Experiences outside work | Written Agreement to set forth expectations on the frequency, agreed mode of contact and confidentiality of the relationship | 1 Year, Every 2-6 months, 30-40 min sessions | In person, Email | Mentees and Mentors: -coping with stress -managing work relationships |

Improved work-life balance and time management |

| Mentors also reported: -enhanced organizational and learning skills |

||||||||

| Pololi and Knight [14] | Peer group mentoring for junior faculty | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 8 Month duration and 6 monthly day long sessions | In person | Sense of empowerment and personal transformation | Participants learnt to recognize, value, and ultimately rely upon the wisdom and diverse expertise of their peers |

| Chandrasekhara [12] | Group mentoring for gastroenterology trainees | Voluntary | Gastroenterology trainee | No agreement | 2-3 monthly meetings | In person | Not specified | Not specified |

Table 2: Overview of organization and outcomes of mentoring programs.

Overcoming common challenges

The challenges of NPG mentoring include dissonance in descriptions of the practice, conflation of peer, near-peer and group mentoring, determination as to how mentors were selected, the presence of disparate levels of commitment and expectations on the part of the peers and near peers and a lack of clarity on their goals and responsibilities [9-11,13]. This results in a wide variety of conceptions about NPG mentoring.

The presence of an informal environment amongst peers of a similar rank does raise concerns about accountability. Some structured programs have instituted codes of conduct [12] and signed agreements that impose penalties and even expulsion should rules be breeched [9-11,13].

An issue more difficult to legislate for is the potential for unhealthy competition amongst the mentees particularly when funding and opportunities for publications are limited [9-11,12].

Discussion

Thematic analysis of the key features of NPG mentoring allows the forwarding of the first evidence based definition of this form of mentoring. NPG mentoring is characterised by “voluntary collaboration between colleagues of similar rank and experience and common academic interests on mutually beneficial structured fixed term projects. These processes often include a senior clinician who facilitates discussions, provides personalized support and feedback and oversees the mentoring process. Effective NPG mentoring nurtures long term friendships and professional collaborations between peers”.

It is perhaps this social approach strengthened by a basic yet flexible structure that draws curriculum and program designers struggling to imbue their projects with holistic support for learners to NPG mentoring. Many programs continue to struggle with shortages of senior, experienced mentors and increasing competition for their time as they struggle to balance academic, clinical and administrative duties with their work life balance. NPG mentoring’s ability to set out clearly defined short tasks with achievable goals to be carried out in social settings and outside the work environment may provide the answer to part of the problems facing curriculum designers.

Having a specific approach replete with mentor and mentee training, clearly defined goals, roles, responsibilities, code of conduct and oversight of the project, specified timings, frequency and duration of meetings and facilitators who will support more than one mentee using a combination of face-to-face and email, texts messaging and video-conferencing allows help to readily available for all learners. Guiding peer and near-peer mentors through specific tasks that can be objectively reviewed helps build more personable ties that promise more holistic and honest feedback and nurture more enduring ties that may extend to other projects whilst ensuring the content and nature of the support can be reviewed. Flexibility and a largely informal approach helps monitor and support evolving relationships between peers and between facilitator and peers throughout the various stages of the mentoring process.

These features make NPG mentoring an attractive partner to supplement novice mentoring to provide timely, appropriate, contextualized, individualized and holistic support.

Perhaps another attraction of NPG mentoring is its ability to protect against abuse of the mentoring relationships, which is a growing concern in novice mentoring [22]. The presence of peers and near peers provide immediate and continuous oversight of the mentoring process is seen a s protective of mentoring abuse though increasing employ of facilitated peer mentoring is seen to improve accountability and early identification of potential conflicts and unhealthy competition amongst peers.

The combination of NPG and novice mentoring also offers an effective means of multidisciplinary mentoring in Palliative Medicine, Pediatrics and Geriatrics. It also raises the possibility of mentoring by near peers from different specialties supporting learners from diverse clinical backgrounds, thus enhancing interprofessional understanding.

Limitations

However, whilst this review has advanced understanding of NPG mentoring and as a potential partner to novice mentoring, the validity of such conclusions is constrained by the number of papers available, their focus upon short term publications and academic processes which skew understanding of NPG mentoring and open to conflation of terms and practices. Potential differences between the relational dynamics in perspective pieces on near peer and peer mentoring may be glossed over. There is also concern that group mentoring in this remains narrowly focused upon near peer and peer mentoring despite being described in a variety of settings not least those involving more than one mentor and those featuring more than learners of different experience and rank. In truth, it could be said that this review considers a very specific form of NPG mentoring.

A lack of descriptions of the dynamics and evolution of NPG mentoring relationships is also a key concern raising doubts not only as to the presence of a clear understanding of NPG mentoring but also about potential blending with novice mentoring.

Future research

With its goals of supporting novice mentoring through provision of more timely and specific support for mentees, the gaps discussed above demand prospective and holistic scrutiny. Future research requires use of a mixed methods approach and involvement of stakeholders, host organizations, the mentors and the near peer and peer mentees and careful consideration of the group dynamics. Ethnographic study of the mentoring culture and interactions within the mentoring groups and individual one-to-one mentor-mentee interactions are also called for to validate this potentially useful support mechanism within Palliative Medicine’s armoury.

References

- Sng JH, Pei Y, Toh YP, Peh TY, Neo SH, et al. (2017) Mentoring relationships between senior physicians and junior doctors and/or medical students: A thematic review. Med Teach 39: 866-875.

- Toh YP, Lam B, Soo J, Linus CKL, Krishna L (2017) Developing palliative care physicians through mentoring relationships. Palliat Med Care 4: 1-6.

- Yeam CT, Loo TWW, Ee HFM, Kanesvaran R, Krishna LKR (2016) An evidence-based evaluation of prevailing learning theories on mentoring in palliative medicine. Palliat Med Care 3: 1-7.

- Wu JT, Wahab MT, Ikbal MF, Loo TWW, Kanesvaran R, et al. (2016) Toward an Interprofessional Mentoring Program in Palliative Care - A Review of Undergraduate and Postgraduate Mentoring in Medicine, Nursing, Surgery and Social Work. J Palliat Care Med 6: 292.

- Wahab MT, Wu JT, Ikbal MF, Loo TWW, Kanesvaran R, et al. (2016) Creating effective interprofessional mentoring relationships in palliative care- lessons from medicine, nursing, surgery and social work. J Palliat Care Med 6: 290.

- Loo TWW, Ikbal MF, Wu JT, Wahab MT, Yeam CT, et al. (2017). Towards a practice guided evidence based theory of mentoring in palliative care. J Palliat Care Med 7: 1.

- Files JA, Blair JE, Mayer AP, Ko MG (2008) Facilitated peer mentorship: A pilot program for academic advancement of female medical faculty. J Women's Health 17: 1009-1015.

- Mayer AP, Blair JE, Ko MG, Patel SI, Files JA (2014) Long-term follow-up of a facilitated peer mentoring program. Med Teach 36: 260-266.

- Varkey P, Jatoi A, Williams A, Mayer A, Ko M, et al. (2012) The positive impact of a facilitated peer mentoring program on academic skills of women faculty. BMC medical education 12: 14.

- Bussey-Jones J, Bernstein L, Higgins S, Malebranche D, Paranjape A, et al (2006) Repaving the road to academic success: The IMeRGE approach to peer mentoring. Acad Med 81: 674-679.

- Webb J, Brightwell A, Sarkar P, Rabbie R, Chakravorty I (2015) Peer mentoring for core medical trainees: Uptake and impact. Postgrad Med J 91: 188-192.

- Chandrasekhara V (2010) The benefits of a gastroenterology fellows club. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 72: 601-602.

- Mayer AP, Files JA, Ko MG, Blair JE (2009) The academic quilting bee. J Gen Inter Med 24: 427-429.

- Pololi L, Knight S (2005) Mentoring faculty in academic medicine. A new paradigm? J Gen Inter Med 20: 866-870.

- Lin J, Chew YR, Toh YP, Krishna LKRK (2017) Mentoring in nursing: An integrative review of commentaries, editorials and perspectives papers. Nurse Educator.

- Toh YP, Karthik R, Teo CC, Suppiah S, Siew LC, et al. (2017). Toward mentoring in palliative social work: A narrative review of mentoring programs in social work. American J Hospice Palliat Med

- Yap HW, Chua J, Toh YP, Choi HJ, Mattar S, et al. (2017) Thematic review of mentoring in occupational therapy and physiotherapy between 2000 and 2015, sitting occupational therapy and physiotherapy in a holistic palliative medicine multidisciplinary mentoring program. J Palliat Care Pain Manage 2: 1-10.

- World Health Organization (2008) Classifying health workers: Mapping occupations to the international standard classification. pp: 1-14.

- Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A (2010) A systematic review of qualitative research on the meaning and characteristics of mentoring in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med 25: 72-78.

- Haig A, Dozier M (2003) BEME guide no. 3: Systematic searching for evidence in medical education--part 2: Constructing searches. Med Teach 25: 463-484.

- Institute TJB (2014) Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers' Manual 2014 Edition. In: The Joanna Briggs Institute.

- Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3: 77-101.

- Gordon M, Gibbs T (2014) Stories statement: Publication standards for healthcare education evidence synthesis. BMC Med 12: 143.

Citation: Tan B, Toh YL, Toh YP, Kanesvaran R, Krishna LKR (2017) Extending Mentoring in Palliative Medicine - Systematic Review on Peer, Near-Peer and Group Mentoring in General Medicine. J Palliat Care Med 7:323. DOI: 10.4172/2165-7386.1000323

Copyright: ©2017 Tan B, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Conferences

42nd Global Conference on Nursing Care & Patient Safety

Toronto, CanadaRecommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 4787

- [From(publication date): 0-2017 - Dec 11, 2024]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 4079

- PDF downloads: 708