Exploring the Attitudes and Beliefs of the Relatives of Sudanese Patients with Mental Disorders: A Focus Group Study on Mental Illness, Traditional Healing and Modern Psychiatric Treatment

Received: 01-Feb-2023 / Manuscript No. ijrdpl-22-84735 / Editor assigned: 03-Feb-2023 / PreQC No. ijrdpl-22-84735 / Reviewed: 17-Feb-2023 / QC No. ijrdpl-22-84735 / Revised: 21-Feb-2023 / Manuscript No. ijrdpl-22-84735 / Accepted Date: 27-Feb-2023 / Published Date: 28-Feb-2023 QI No. / ijrdpl-22-84735

Abstract

Pathways patients take to psychiatric care reflect the nature of the services available and the popular belief model about mental illness. We aimed to study the help-seeking behavior and to determine the prevalence of contact with psychiatric services among patients with mental disorders receiving traditional treatment in the traditional healers centers (THC) in Sudan. All in-patients with mental disorders receiving treatment in the THC, socio-demographic data,information on help-seeking pathways and experiences of contact with psychiatric services were determined through

face–to-face interviews and Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). We found that prior to presenting to traditional healers 48.1% (195) had previous contact with the psychiatric services and 51.9 %( 210) did not. Many of those who contacted psychiatric services attributed their illness to supernatural causes such as Satan and wrong doing. There were 45 (23.1%) (p=0.003) of those with history of alcohol abuse and 35(17.9%) (p= 0.001) with drug abuse have contacted psychiatric services before receiving traditional healing treatment. History of contact with psychiatric services is common among patient with psychiatric disorders receiving treatment in the THC in central Sudan. Collaboration between psychiatrist and traditional healers is necessary for better management of psychiatric patients.

Keywords

Culture; Mental health; Help-seeking; Traditional healing; Psychiatric services; Mental disorders; Psychiatric patients; Sudan; Mental health services; Traditional healers

Introduction

Mental health in Sudan

The establishment of psychiatric services in Sudan is an interesting experiment in a developing country. Prior to World War II there were hardly any organized psychiatric services. By 1950, the Clinic for Nervous Disorders, Khartoum North, was well established and the Kober Institution was built later to cater for 120 forensic psychiatric patients. This was followed by the establishment of four psychiatric units in provincial capitals at Wad Madni, Port-Sudan, El Obeid and Atbara. In 1964, a 30-bed psychiatric ward was built in Khartoum general hospital. Psychiatry in Sudan began in the 1950s under the guidance of the late Professor El Tigani El Mahi. He pioneered, among other things, rural services and the open-door policy. His successor, Dr Taha A. Baasher, shouldered the responsibility and extended services to more peripheral areas of the country. He established the Mental Health Association of Sudan and the Sudanese Association of Psychiatrists. In 1971, Omdurman Psychiatric Hospital was established as the national mental hospital. However, since then, mental health services failed to extend beyond a few specialized units attached to state hospitals. This has been mainly due to a shortage in qualified staff, such as psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and psychiatric nurses. In term of facilities, mental health is not yet part of the PHC system. Nationally there are 0.2 psychiatric beds per 10,000 populations: 0.18 in mental hospitals and 0.02 in general hospitals.

Mental hospitals in sudan

There are two mental hospitals available in the country for a total of 0.86 beds per 100,000 populations. These facilities are organizationally integrated with mental health outpatient facilities. Thirty percent of patients treated are female and 13% are children and adolescents. The patients admitted to mental hospitals primarily belong to the following diagnostic group: mental and [1-3] behavioral disorders due to psychoactive substance use (10%), schizophrenia and related illnesses diagnostic group (15%), mood disorders (22%), neurotic stress-related and somatoform disorders (18%), disorders of adult personality and behaviour (11%) and others, such as mental retardation, epilepsy (24%). Twenty four percent of the patients were admitted involuntarily and 11-20% of the patients were restrained or secluded. The occupancy rate of these hospitals is 20%. The average number of days spent in mental hospitals is 35 days. All patients spend less than one year in mental hospitals. The number of beds has increased by 62 % in the last five years; the proportion of involuntary admissions to psychiatric inpatient units is 17% while 11-20% of the patients were restrained or secluded at least once in the past year (WHO AIMS-Report-Sudan 2009). All mental hospitals and the majority of inpatient and outpatient facilities in the country are located in Khartoum city; the capital and the largest city in Sudan. Such a distribution of facilities prevents access to mental health services for rural users. There are 7 community-based residential facilities in Sudan (more than 7, but the most important are 7 traditional healer centers) with an estimated total of 760 beds.

Definition of traditional medicine

WHO (1976) defines traditional medicine as `the sum total of all the knowledge and practices, whether explicable or not, used in diagnosis, prevention and elimination of physical, mental or social imbalance and relying exclusively on practical experiences and observations handed down from generation to generation whether verbally or in writing`. Literature has highlighted that traditional healers are often seen as the primary agents for psychosocial problems in developing countries, estimating their shares services range as high as 45% to 60%. Estimated that 80% of populations living in rural areas in developing countries depend on traditional medicine for their health needs.

Definition of traditional healer

A traditional healer is defined by the WHO` as a person recognized by the community in which he lives as competent to provide health care using plants, animals or mineral substances and certain other methods based on the social, cultural and religious background, as well as on the knowledge attitudes and beliefs that are prevalent in the community regarding physical mental and social [4-7] wellbeing and the causation of disease and disability`. A traditional healer is an educated or lay person who claims ability or a healing power to cure ailments, or a particular skill to treat specific types of complaints or afflictions, and who might have gained a reputation in his own community or elsewhere. They may base their powers or practice on religion, the supernatural, experience, apprenticeship or family heritage. Traditional healers may be males or females and are usually adult. It was reported by WHO that traditional medicine is so successful in Sudan that is extensively used in the control of neuroses and alcoholism, and as such possesses a potential for research on the treatment and rehabilitation of neurotic reactions ,alcoholism and drug dependency. Traditional medicines present several valuable solutions to the management of culturally linked diseases and other health problems in Sudan. The reason for this success is that it is an integral part of the people culture and they have deep confidence in it. The methods and techniques employed are guarded secrets by the traditional healers. Reported that: ((in Sudan the traditional healing methods are shaped by the religious, spiritual and cultural factors of different ethnic population groups. The practice is common in urban as well as rural populations. Traditional healers may require long stay of patients and this may prevent early detection of disease and early medical intervention by modern psychiatry)) (WHOAIMS Report. Traditional beliefs and religion play an important role in the socio-cultural and political life of the people in the countries of the eastern Mediterranean region. The family and community hold a central position in the life of the individual, and they make a tremendous contribution to the therapeutic process. Native faith healers are found in all parts of the eastern Mediterranean region, where they are held in high regard and are considered to be spiritual or moral guides. They are consulted for a range of ailments including physical illness, emotional problems, and congenital defects, or disappointments in love, family, or business. The WHO studies of pathways to care have shown native faith healers to be an important source of care for people who ultimately attend psychiatric services.

Pathways to psychiatric care and the help-seeking behavior

Many patients suffering from psychiatric disorders seek nonprofessional care before attending specialized services. Erinosho in Nigeria reported that people often sought care from traditional healers before making any contact with modern psychiatric facilities. Reported that the majority of the mentally ill in Nigeria are cared for outside the mental health system mostly by traditional healers. The situation in Sudan is not different from what has been reported in Nigeria and other Africans and Arab countries. Investigated the helpseeking behaviour of patients referred to the psychiatric department in United Arab Emirates.; they found that 44.8% consulted faith healers. A similar a study by Sayed in Saud Arabia found 70% of patients resorted to traditional healers sometime during the course of their current illness; of these 60% had visited the traditional healer before seeking psychiatric treatment. In Turkey (Guner-Kucukkaya, and Unal determined the help-seeking behaviors, prior to attending a psychiatric outpatient clinic, among Turkish patients. More than 50% used alternative therapies rather than conventional treatment. Campion and Bhugra studied psychiatric patients attending a hospital in Tamil Nadu, in South India and found 89 (%45) patients had sought between 1 and 15 sessions from either Hindu, Muslim or Christian healers. In Malaysia, Salleh (1989) investigated Malay patients attending psychiatric clinics for the first time. He found that 76 (73.1%) patients consulted traditional healer’s prior visiting psychiatric clinic. Razali and Najib explored the help-seeking behavior of Malay psychiatric patients. They found 69% had visited traditional healers before consulting psychiatrists. Patients who had consulted traditional healers were significantly delayed in getting psychiatric treatment compared with those who had not consulted them. A similar study was conducted by Phang, Marhani and Salina (2010) among 50 in-patients with firstepisode psychosis in hospital Kuala Lumpur in Malaysia. They found that 27 (54%) of the patients had at least one contact with traditional healers prior to consulting psychiatric service. Kurihara took a study to trace the help-seeking pathway of mental patients and to elucidate the role of traditional healing in Bali in Indonesia. They found 47 (87.0%) patients consulted a healer before visiting the mental hospital and the consultation with the healers was associated with treatment delay. Patel, Simunyu, and Gwanzura (1997) reported that pathways to care for mental illness are diverse and are dependent on the socio-cultural and the economic factors. Traditional care providers provided explanations more often than biomedical care providers. Explanations given were most often spiritual. Adewuya found that the spiritual healers were the preferred treatment option, endorsed by 41% of respondents. Thirty percent of the respondents endorsed traditional healers, and 29% endorsed hospitals and western medicine. Correlates of preference for spiritual and traditional healers included female gender, never having provided care for persons with mental illness, endorsement of supernatural causation of mental illness, and lower education. Gureje, studied the pathways patients take to psychiatric care that reflect the nature of the services available and the popular beliefs about mental illness. Studying the pathways may help identify sources of delay in the receipt of care, and suggests possible improvements. Patients who consult traditional healers first, tend to arrive at a tertiary psychiatric service much later than those who consult other carers. Alem, in a study carried out in Ethiopia, reported that traditional treatment methods were preferred more often for treating symptoms of mental disorders and modern medicine was preferred more often for treating physical diseases or symptoms. Bertrand reported that; people often seek advice from monks at the pagoda, traditional doctors when they are ill, and consult medical practitioners only as a last resort. Appiah-Poku, in Ghana reported that there was a greater delay in presenting to mental health service if the patient had seen a traditional healer or pastor. It is quite obvious from previous studies and from daily psychiatric practice in many developing countries that most of the people with mental disorders consult traditional healers first and they receive care outside the mental health system. Many patients with mental illness who consult traditional healers first will appear very late to the psychiatric services. Campion and Bhugra stated that, Community surveys can be employed to ascertain rates of mental illness and help-seeking from religious healers, but these are not necessarily cost-effective.

One would need large samples to collect adequate numbers of patients with mental illness and those who have followed religious healing. They mentioned that, two further methods of ascertaining the role of traditional healing in psychiatric care can be used. One is to investigate a group of psychiatric patients and find out whether they had sought help from traditional healers and the outcome of this help, along with other factors, to determine the accessibility and acceptability of such assistance. The second method is to assess the psychiatric status of those attending places of traditional healing. The second methodological approach; where healers and those in the process of healing are studied, carries with it the problem of "voyeurism" and is seen as critical of or competitive with, healers. Initial explorations suggest this method to be somewhat difficult and impractical (Campion and Bhugra. Few studies were carried out to assess the psychiatric status of those attending places of traditional healing. Saeed, in Pakistan, Satija and Nathawat, Raguram, Padmavati in India and Abbo in Uganda had approached patients with mental disorders in the traditional healers centres care setting. Our study was conducted in the traditional healers setting because we found that will be the most suitable methodological approach through which we can achieve the aims of our research which were

1. To determine the proportion of patients attending traditional healers centres for healing who had sought psychiatric treatment and to ascertain details of these experiences.

2. To determine the socio-demographic factors important in this type of help-seeking.

3. To ascertain whether visits to traditional healer were related to perceived causes of illness and whether such treatment was considered a valuable adjunct to medical and psychiatric treatment.

Methods

This is a descriptive cross-sectional study conducted in the traditional healer’s centers in central Sudan over a 12 months period from July 2009 until June 2010. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the research ethical committee in the directorate of research in the federal ministry of health in Sudan

Study area

Thirty famous traditional healers centres in and around the capital Khartoum and the nearby states were each assigned a number from 1 to 30. Then the researchers asked a third party to randomly choose 10 of these numbers.

This resulted in 10 famous traditional healers centres in and around Khartoum, Gezira, White and Blue Nile states in central Sudan being randomly selected. The director of each traditional centre was approached personally by the principal investigator and the research team. An official letter was delivered to each centre explaining the purpose of the study and consent for joining the study was obtained from each centre before the start of data collections from patients.

Sample

We included all in-patients with mental disorders receiving treatment in the traditional healer’s centers in central Sudan. Sample size was calculated using the Kish and Leslie formula for single proportions for descriptive study. The calculation assumed a frequency of 48% for mental disorders at the traditional healer centres (based on the prevalence of mental disorders among users of traditional healers. for a 95% confidence interval and a precision of p < .05, a total of 405 inpatients with mental disorders were included in the study (Kish & Frankel, 1974).

Instrument

The data collecting instrument used was a semi-structured questionnaire designed for the purpose of this study. It includes sociodemographic data, duration of the illness, family history of mental illness, views of patients and relatives on the precipitating factors and reasons for the mental illness, views of patients and relatives on psychiatric services and traditional healing. Information on helpseeking pathways and experience of contact with the medical and psychiatric services were assessed. The psychiatric diagnosis was made by using the (MINI).

The mini international neuropsychiatry interview (MINI)

The MINI is the most widely used psychiatric structured diagnostic interview instrument in the world. The MINI is used by mental health professionals and health organizations in more than 100 countries. The MINI has been validated against the much longer Structure Clinical Interview for DSM diagnoses (SCID-P) in English and French and against the Composite International Diagnostic Interview for ICD- 10 (CIDI) in English, French and Arabic. The MINI Arabic version-5 used in this study was validated through its use in many studies and surveys that were conducted in Arab countries (Ghanem , Gadallah, Meky, Mourad, & El-Kholy. The MINI has been validated in Sudan in 2007-2008 by a team of researchers from the department of psychiatry, University of Khartoum and the institute of psychiatry Oslo University Norway and has been used in many studies conducted in Sudan (Salah, Abdelrahman, Lien, Eide, Martinez and Hauff.

Procedure

Data were collected through face-to-face interviews using structured questionnaire by 5 qualified researchers’ clinical psychologists, who underwent training on the research instrument before the start of data collection. All patients receiving traditional healing treatment in all of the traditional healer’s centers during the study period were approached personally by the principal investigator and the research team and consent was obtained from each patient and relatives before we interviewed them with the questionnaire and the MINI.

Statistical analysis

All data analyses were conducted using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Science) software version 19 for windows. All data was tabulated and expressed in proportions. Descriptive statistics were reported as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, means (SD) for normally distributed continues variables and medians (SD) for nonparametric variables. The Chi-square test (X2) test was used to assess the correlates of psychiatric service contact versus socio-demographic factors, and other service choice factors and the diagnosis. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. We also performed multivariate analysis, to estimate the relative importance of predictors of contact with psychiatric services among patients treated in the traditional healer’s centres. Logistic Regression analysis was conducted Tabachnich & Fidell. The significance of the individual indicators was assessed by the Wald statistic. In order to compare the relative importance of the predictors, odds ratios were calculated.

Predictors of having visited a psychiatric clinic

To test the relationships between categorical variables, contingency table (crosstabs) analysis by Pearson chi-squared (χ2) statistics was initially performed. However, this two-dimensional perspective may miss the complex nature of relationships. Therefore, the data were subjected to statistical modelling, to determine which, if any, socio-demographic factors, illness history variables, or mental illness attributions were independently related to patients having previously visited a psychiatric clinic. As the outcome variable ‘visited a psychiatric clinic’ is a binary categorical variable rather than continuous, simple logistic regression modelling (SLR) and hierarchical logistic regression modelling (HLR) were performed. The SLR models investigated the impact of socio-demographic factors on the outcome. The HLR models then investigated the impact of illness history, and illness attributions on the outcome, after controlling for the influence of socio-demographic factors on the outcome. The binary dependent variable was posited as ‘visited psychiatric clinic’ (with “1” representing visited psychiatric clinic and “0” representing did not). The socio-demographic independent variables were posited as age, gender, residence, marital status, education, occupation, and distance from health service. The illness history independent variables were posited as diagnosis, duration of untreated illness, previous history of mental illness, previous history of medical illness, family history of medical illness, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and precipitating factors. The mental illness attribution independent variables were posited as jinn possession, Satan, evil spirit, wrongdoing, magic, or something else. SLR and HLR modelling were performed using SPSS (IBM Corporation, Version 19.0). The criterion for statistical significance was p<.05; with p<.01 meaning very significant, and p<.001 meaning highly significant.

Sample Size for Logistic Regression

For logistic regression, the minimum ratio of valid cases to independent variables is 10 to 1, or preferably 20 to 1. There were 405 valid cases and 7 independent variables for the SLR socio-demographic model (ratio of 57.86 to 1); 8 independent variables for the HLR illness history model (ratio of 50.63 to 1); and 6 independent variables for the HLR illness attributions model (ratio of 67.50 to 1). This ratio of cases satisfies the minimum ratio of 10 to 1 and the preferred ratio of 20 to 1.

Results

The aim of our current report is to provide information on helpseeking pathways and prevalence of contact with psychiatric services and it is correlates on patient with mental illness receiving traditional healing treatment in the traditional healer’s centres in Sudan. The detailed results of the socio-demographic characteristics of the patients included in this study are available in a previously published report. We were able to include 405 patients. There were 195 (48.1%) patient had previous contact with the psychiatric services and 210 (51.9 %) did not.

The socio-demographic characteristics in relation to psychiatric services contact

Psychiatric service contact in relation to the education level of the patients shows significant results (p=0.02) where 55.7% with secondary school education and 62.1% with university degrees had psychiatric service contact if compared to those who never been to school (43.5%) or only have primary school education (45.9%). Psychiatric service contact in relation to the occupational status of the patients shows significant results (p=0.001) where 102(61.1%) of the employed patient contacted the psychiatric services compared to 65(38.9%) of the employed who did not made any contact with the psychiatric services. There were 74 (38.9%) unemployed who contacted the psychiatric services compared to 116 (61.1%) unemployed did not made any contact with the psychiatric services. only 19(39.6%) student visited the psychiatric services and 29 (60.4%) of the student did not visited the psychiatric services. There was no significant correlation in regard to patient’s age, sex, residence, marital status and the contact with the psychiatric services.

Logistic regression: socio-demographic variables

The first simple logistic regression model examined the impact of socio-demographic factors on the likelihood of patients having visited a psychiatric clinic. The results of this model are presented in, with the B coefficient, odds ratio (OR), and 95% confidence interval for each category of the demographic predictor variables for "visited psychiatric clinic". Entry of socio-demographic factors in the logistic regression produced a significant model, χ2=40.35, df=14, p<:001. Education, occupation, and distance from the health centre were significant. Examination of the variable categories showed that patients with a university education were almost three times more likely to have visited a psychiatric clinic [OR = 2.756, CI: 1.115 – 6.816, p< .05]; patients who were employed were 66% likely to have been visited a psychiatric clinic [OR = .339, CI: .210 – .548, p< .001]; patients who were unemployed were 63% less likely to have been visited a psychiatric clinic [OR = .366, CI: .171 – .784, p< .01]; and patients who lived far away from a health centre were almost twice as likely to have visited a psychiatric clinic [OR = 1.753, CI: 1.099 – 2.795, p< .05]. Age, sex, and marital status were not significant.

Illness history in relation to psychiatric services contact

The longer the duration of the untreated illness (DUI) shows significant association in relation to contact with psychiatric services. There were 60 (57.7%) patient their DUI was more than 13 months contacted the psychiatric service (p=0.01). There were 60(69.8%) patients with history of medical illness have contacted psychiatric services, and 26(30.2%) they didn`t contacted psychiatric services, (p=0.001). Also those with history of alcohol abuse (p=0.003) and drug abuse (p= 0.001) shows significant statistical association results in relation to contact with the psychiatric service respectively.

Logistic regression: illness history variables

Hierarchical logistic regression carried out in two steps, modelled the extent to which illness history variables predicted the likelihood of patients having visited a psychiatric clinic, while controlling for sociodemographic factors in Step 1. Entry of illness history variables in Step 2 of the logistic regression produced a significant model, χ2 =115.575, df=33, p<:001. The model fit statistic shows the model significantly improved on the second step (-2LL reduced from 520.541 in Step 1 to 449.319 in Step 2). The results are presented in, with the B coefficient, odds ratio (OR), and 95% confidence interval for each category of the illness history predictor variables for "visited a psychiatric clinic". Diagnosis, past history of medical illness, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, and precipitating factors were significant. Examination of the variable categories revealed that patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder were almost 3.5 times more likely to have visited a psychiatric clinic (OR = 3.466, CI: 1.059 – 11.346, p< .05); patients with social phobia were over 10 times more likely to have been visited a psychiatric clinic (OR = 10.390, CI: 1.334 – 80.951, p< .05). Patients with obsessive compulsive disorder were almost 6 times more likely to have been visited a psychiatric clinic (OR = 5.918, CI: 1.049 – 33.389, p< .05). Patients with a history of medical illness were almost 4 times more likely to have been visited a psychiatric clinic (OR = 3.863, CI: 1.929 – 7.737, p< .001). Patients who abused alcohol were 61% less likely to have been visited a psychiatric clinic [OR = .386, CI: .153 – .972, p< .05]; and patients who abused drugs were almost 6 times more likely to have been visited a psychiatric clinic (OR = 5.791, CI: .153 – .972, p< .05). Duration of untreated illness, past history of mental illness, and family history of mental illness were not significant.

The precipitating factors and the perceived reasons of the mental illness in relation to contact with the psychiatric services

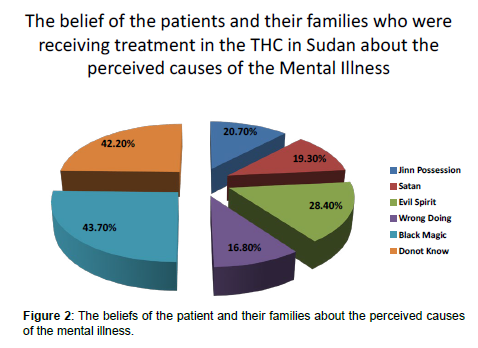

Many attributed precipitating factors for the mental illness such as family and social factors, financial, legal, and ill health shows signification correlation in relation to contact with the psychiatric services (p=0.001). Of the total sample, 20.7% (84) attributed their mental illness to jinn possession, 19.3% (78) to Satan, 28.4% (115) to evil sprits, 16.8% (68) to wrong doing, 43.7% (177) to black magic and 42.2% (171) attributed it to another unknown causes; Figure 2. Some of those who have visited the psychiatric services they do not relate their illness to supernatural causes such as evil spirit 157 (54.1%) and jinn possession 161(50.2%). On the other hand, only about 38(33%) who attributed their mental illness to evil spirit has visited the psychiatric services. About 77 (67%) who attributed their mental illness to evil sprit they did not contacted the psychiatric services; that shows significant statistical association (p=0.001). Further more, there was significant correlation and association between the contact with the psychiatric services and those who do not attributed their mental illness to wrong doing, committed sins and doing things against God orders (P=0.01). There were 153 (45.4%) who do not attributed their mental illness to wrong doing they visited the psychiatric services and only 42 (61.8%) who attributed their mental illness to wrong doing have visited the psychiatric services.

Logistic regression: family attributions of mental illness

Hierarchical logistic regression carried out in two steps, modelled the extent to which family attributions of mental illness variables predicted the likelihood of patients having visited a psychiatric clinic, while controlling socio-demographic factors in Step 1. Entry of attribution variables in Step 2 of the logistic regression produced a significant model, χ2 =80.027, df=23, p<:001. The model fit statistic shows the model significantly improved on the second step (-2LL reduced from 520.541 in Step 1 to 480.867 in Step 2). The results are presented in , with the B coefficient, odds ratio (OR), and 95% confidence interval for each category of the illness history predictor variables for "visited a psychiatric clinic." Evil spirit, Satan, and wrongdoing were significant. Examination of the variable categories revealed that patients whose family attributed their mental illness to evil spirit were over three times more likely to have visited a psychiatric clinic (OR = 3.431, CI: 1.805 – 6.524, p< .001). Patients whose family attributed their mental illness to Satan were 51% less likely to have been visited a psychiatric clinic (OR = .491, CI: .257 – .941, p< .05); finally, patients whose family attributed their mental illness to wrongdoing were 58% less likely to have visited a psychiatric clinic (OR = .421, CI: .213 – .828, p< .05). Illness attributions of jinn, magic, and something else, were not significant.

Final binary logistic regression (after dropping nonsignificant variables from the model): predicting the propensity to visit a psychiatric clinic in Sudan

The hypothesis that: illness history and family attributions of mental illness would increase the likelihood (odds) of a patient having visited a psychiatric clinic, after controlling for socio-demographic factors, was supported. Factors that increased the likelihood of visiting a psychiatric clinic are (in order), family attributing mental illness to evil spirits, drug abuse, and longer duration of untreated illness. A twostage hierarchical multiple logistic regression model was determined to test H1, with propensity to visit a psychiatric clinic posited as the dependent variable. In Block 1 of the regression model, the demographic factors of age, sex, residence, marital status, education, occupation, and healthcare centre were posited as the independent variables, to control for their presumed influence on the outcome. In Block 2 of the model, the illness history and family attribution of mental illness variables were posited as the independent variables, to examine their unique contribution in predicting the odds of a patient visiting a psychiatric clinic, after controlling for demographic factors. Displays the regression coefficients (B), standard error of B (SE (B)), odds ratio (OR), and 95% confidence interval for each category of the explanatory variables for "visited a psychiatric clinic." A total of 405 cases were analysed. The Block 1 model was significantly reliable (χ2=19.170, df = 2, p<.001). 61% of the predictions were accurate, with 69% who did not visit a psychiatric clinic accurately classified, but only 52% who did visit accurately classified (which is not much greater than randomly guessing, UNT, 2012). The demographic variables in Block 1 revealed that the odds of visiting a psychiatric clinic were 59.30% lower if a patient was unemployed, as compared with a patient who was employed (the reference category) [OR = .407, CI: .269 – .623, p< .001]. The odds of visiting a psychiatric clinic was 58.20% lower if a patient was a student, as opposed to employed (the reference category) [OR = .418, CI: .216 – .805, p< .01]. Entering the illness history and family attribution variables in Block 2 of the regression, produced a significant model, χ2 =80.884, df=9, p<.001. The model fit statistic shows the model significantly improved on Block 1 (-2LL reduced from 541.72 in Block 1 to 480.01 in Block 2). 75% of predictions were accurate, with 76% who did not visit a psychiatric clinic accurately classified, and 74% who did visit a psychiatric clinic accurately classified. The predictors in Block 2 show that, after controlling for demographic factors, the odds of visiting a psychiatric clinic increase with longer duration of untreated illness [B=.013, Beta Positive, OR = 1.013, CI: 1.000 – 1.026, p< .05]. We can estimate the odds of visiting a psychiatric clinic is increased by a factor of 1.013 for every 1-month increase in duration of untreated illness. We are 95% confident the increase in odds is between 1.000 and 1.026. The odds of a visit are also 3.31times greater with drug abuse [OR = 3.314, CI: 1.557 – 7.054, p< .01].The odds are 3.52 times greater if the family attribute the illness to evil spirits[OR = 3.520, CI: 2.078 – 5.963, p< .001].In contrast, the odds of a visit decrease (it is less likely) by 55.8% if the family attribute mental illness to wrongdoing [OR = .442, CI: .239 – .817, p< .01]; the odds of a visit decrease by 57.8% if a patient has ‘nothing’ as a precipitating factor, as opposed to a family/social precipitating factor (the reference category) [OR = .422, CI: .252 – .706, p< .001]. We can conclude that the strongest predictors of the propensity to visit a psychiatric clinic by any Maseed patient are: family attributions of evil spirit, followed by drug abuse.

The traditional healers and the health services factors in relation to contact with the psychiatric services

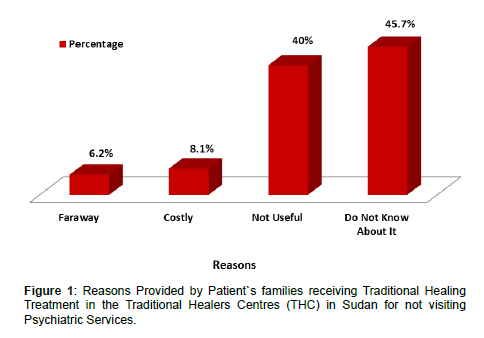

Patient`s and families provided many reasons for not visiting the psychiatric services. There were 13 (6.3%) patients who said that the psychiatric services were far away from them, 17(8.1%) said it is costly, 84(40%) indicated that the psychiatric services is not useful, and 96(45.7%) they simply mentioned that they do not know about these services; Figure 1. People do not contact traditional healers because the cost of treatment in the traditional healers centers is less compared to psychiatric services, as there were 160 (51.3) patients who said the cost is not less compared to psychiatric services had visited psychiatric services (p=0.01).There were 52 (71.2%) of those patients who contacted psychiatric services before coming to the traditional healers centers their psychiatric medications were stopped by the traditional healers. There were 143 (73.3%) patients who contacted psychiatric services they continue taking their psychiatric medication while receiving traditional treatment. This was quite important and statistically significant result (p=0.001). There were 156(54.9%) patients who have available health service facility near to their home they did not made any attempt to contact psychiatric services. This result was statistically significant (p=0.03). Further more, people come to the traditional healer treatment because of the perceived effectiveness of the traditional healing treatment. There were 183 (46.8%) patients who contacted the psychiatric service they belief in the effectiveness of the traditional healing treatment, and 208 (53.2%) of those who did not contacted the psychiatric service and currently receiving traditional healing management they belief in it is effectiveness (p=0.004).

Method patients brought to receive treatment in the traditional healer’s cenres and the perceived reason of the mental illness

Of the total sample there were 93(23%) patients who came voluntarily to receive treatment in the THC and there were 312 (77%) who were brought involuntarily by their families or relatives. There were 11 (13.1%) of those who came voluntarily and 73 (86.9%) who were brought involuntarily by their relatives attributed their mental illness to Jinn possession. This was statistically significant association (p=0.009). There were 17 (14.8%) patients of those who came voluntarily and 98(85.2%) who were brought involuntarily by their relatives attributed their mental illness to evil sprit. This was statistically significant association (p=0.008). There were 32 (18.1%) of those who came voluntarily and 141(85.1%) who were brought involuntarily by their relatives attributed their mental illness to black magic. This was statistically significant association (p=0.026). There were 46(49.5%) who came voluntarily visited the psychiatric services and 47 (50.5%) did not. There was no statistical significant association between the method by which patients were brought to THC and the visit to psychiatric services (p=0.4).

Discussion Traditional healing in Sudan In Sudan traditional healing is the most prevalent method for the treatment of mentally sick people mostly due to lack of economic resources, inaccessibility of medical services, and lack of awareness among the population and the high prices of psychiatric services. Generally, traditional healing in Sudan can be divided into two distinct groups: religious healers influenced by Islamic and Arab culture, such as traditional Koranic healers and Sufi healers; nonreligious healers influenced by African culture, such as practitioners’ zar, talasim and kogour. The religious healers are subdivided into two groups; the first group uses only Koranic treatment, derived from certain verses. This involves reading and listening to the Koran with the active participation of the patient. The success of treatment depends on the reliability of the healer and the degree of his belief, in addition to the conviction of the patient and his belief in the Koran as a source of treatment. The second group uses a combination of both Koran and talasim. The types of talasim used are mainly squares filled with symbolic letters which have a hidden spiritual dimension conceived only by the sheikhs as pious, holy men. They contain the 99 attributes (names) of God and some other inherited words from ancient divine books. Healers in this subgroup are influential decision-makers at the individual, family and community level. They are respected not only by their followers, but also by government officials and politicians. Stated that Kogour is a typical African practice found only in the south of Sudan where African culture dominates. It is used by healers who claim to have supernatural powers. It deals with souls in the belief that these souls affect the body. Such healers use their power to cure disease and to solve other problems, such as the control of rain. Mohammed stated that, Zar came to Sudan from Ethiopia and is based on the assumption that supernatural agents or spirits possess a person and may cause him or her some physical and psychological disorders. The zar concept of possession is based on the idea that the spirit makes certain demands that should be fulfilled by the patient or his relatives; otherwise this spirit may cause trouble for all of them. Zar is the dominance of the evil soul over the human being with the intention of hurting the person. Zar is common among Muslims as well as Christians. The sheikhs of zar are usually women. They are responsible for diagnosing and identifying the spirits and their demands and preparing and directing what are called zar parties. These parties use very loud music, vigorous dance and songs with special rhythms. They serve both diagnostic and therapeutic objectives. Most of the patients and their families in Sudan depend mainly on traditional healers and their healing methods as the most accessible and less demanding in term of financial obligations. mentioned that the holistic approach of traditional healing might lead to long-term stability of health; this might explain why in many cases patients would prefer this approach than other techniques that result in short-term relief of symptoms. Therefore, there is a great demand to study those mentally ill patients within the traditional healer system to understand the reasons and factors that brings this long term stability in health. In addition to harmful methods of practices, cases of misuse have been reported due to the lack of regulation on quality control, and the lack of proper use. However, traditional medicine maintains its popularity for historic and cultural reasons. El Gaili is reported until recently interest and concern about mental health was mainly left to religious healer, and such healers continue to see the majority of the mentally ill patients in Sudan. Traditional healers in Sudan perform many valuable services and social benefits to the community, nevertheless traditional healing is not formally institutionalized, as there is no responsible government entity to guide and supervise the delivery of traditional healing services. Therefore, getting accurate figures or numbers of traditional healers and their specialty is extremely difficult, and generally most of the data available on their services is based on estimates. People in Sudan usually go to traditional healers for consultation in each and every aspect of their life. Ahmed, Bremer, and Magzoub stated that traditional healers can also act as family counselors in critical life events such as building a house, marriage, naming a newborn, and may have both judicial and religious functions. They often act as an agent between the physical and spiritual worlds. People usually go to traditional healers to bless them in their work and give them what is called Fatiha (special prayers performed by the sheikh) to bless them in all activities in their lives, and they gave a huge contribution to these centers, what they call Zowara. The poor also contribute with small amount of share or they may take their sheep’s and animals or their agricultural products for donation as a contribution to these centers. Sometimes they may sell their sheep’s and donate the money to these centers as Zowara. It is not a must but they feel ashamed if they come empty-handed to the sheikh whether he is alive or dead. It is a belief that the amount of blessing coming to the people from the visit to the sheikh, depends on the amount of sacrifices (Qurban) that people spend. It has been reported that some couples who have no children visit the sheikh (Traditional Healer) to ask for a child. If they have only girls they ask him for a baby boy. Usually, the sheikh performs prayers on their behalf, and asks God (Allah) to give them what they wish. Sometimes they may go and visit the dead sheikh and move around the grave that was kept under a tall building called Quba. They collect the holy sand of the dead sheikh’s grave and they believed that the sand is blessed. They called that sand Baraka. It has been stated by Deifalla that miraculous cures are attributed to the divine powers of the dead sheikh. This is why they spread the sand all over the body of the patient or they may ask the patient to drink it after they dissolved it in water. Sometimes they hang it on the body or put it in a special place in their house to bless that house. People believe that disobeying the sheikh brings damnation on the followers and their families. They believe in the sheikh’s blessings and regard him as a mediator between the follower as a slave and the Lord. They also believe that the sheikh, whether dead or alive, is capable of rescuing them and pleading on their behalf for help and release from illness. Therefore, the sheikhs in the people’s eyes are true representatives of spiritual power Fadol, Tabagat Wad Daifalla. Both men and women with somatic and physical complaints consult traditional healers for management and treatment. Patients with mental disorders are usually brought by their relatives and families, depending on the condition of the patient. If the patient is severely disturbed and agitated, they put him/her in an isolated dark room especially built for treating the mentally ill patients. They sometimes chain the patient to the room wall or to his bed. Patients were not allowed to move or walk in that room except in chain. They were prohibited to come out of that room until at least 40 days. Sometimes patients succeed in putting off these chain and they escape from the center. Usually these rooms are in the far corners of the traditional healers’ centers. The patients were deprived from all types of food except special porridge made in these centers. The duration that the patient stays in the center varies from 40 days to 6 months or more, depending on his/her symptoms and condition. In some centres the patient’s psychiatric medication, if any, would be stopped by the traditional healers so as not to interfere with their traditional healing methods. Three to five mentally ill patients are usually brought to the famous centers for healing every day. The patients do not come from the local community around the centers, but they will be brought from different parts of Sudan. The patients are usually accompanied by their family members and relatives. Some doctors treating mentally ill patients claim that, most of patients kept in these centers were deprived from food; the patients presented to doctors with Anemia and low Hb level. They were very thin and emaciated, with a lot of physical complications in addition to their psychiatric symptoms. The late professor Eltigani Elmahi stressed that the attitudes of mental health professional towards religious healers should aim to encourage the good quality of practice while trying to end the harmful or faulty methods. However, no enough care and attention has been paid to the people with mental disorders receiving care in these traditional healers’ centres in terms of assessing their conditions and reviewing the system of diagnosis, care and management.

Pathways to care and the help seeking behavior of people with mental illness in Sudan

Traditional healing is the most popular first point of nonpsychiatric help-seeking contact as there were 210 (51.9%) patients receiving traditional healer’s treatment did not contacted psychiatric service prior to coming to the traditional healer centers. On the other hand only 195(48.1%) came in contact with the psychiatric services before consulting traditional healers. Our current study is a traditional healer centre’s setting based study. Our findings are almost similar and can be compared to other pervious hospital based studies. Phang. Various factors seen as vital in having to resort to traditional healers include the type of affliction,the local interpretation of the mental illness, the sociodemograghic status of the patients and the availability of the healers (campion and Bhugra(1997). In a study in South Africa some traditional healers patients claim that, physicians do not have the time to give them the attention they need.They were usally placed in a room with numerous other patients and their individaul requirement are rarly addressed.This was contrasted with traditional healers who were available 24 hours a day 7 days a week and often check on the patient regularly to esure the patient was adhering to the traditional treatment and the patients family were coping with patient needs. A study carried out in Singapore by Chong showed that 24% of the respodent had sought help from traditional healers before consulting psychiatric services.

Socio-demographic characteristics in relation to psychiatric services contact

In our current study there was no significant relation in relation to the sex of the patient, marital status and the area of residence in Sudan and the contact with the psychiatric services. People come to traditional healers centers from all over the country irrespective of their area of their residence. The residence of the patient did not influence their traditional healer or psychiatric consultation. Earlier studies suggested that those residing in rural areas are more likely to use traditional healing Satija and Nathawat . We found significant relation with the educational level of the patient and their occupational status in relation to contact with psychiatric services. Those with secondary school education or university qualification or who are working before they developed their mental illness have more contact with psychiatric services. This may be because they are aware and knowledgeable about these services and it is benefits. This finding is consistent with the finding of Campion and Bhugra in India where they found that those who attained postgraduate education were less likely to seek help from religious healers which reflects westernization achieved in the educational system. The presence of medical and psychiatric services near to patients home is not significantly associated with the contact of these services. There were factors that influence the help-seeking behavior of the patients beyond the availability and accessibility of these services. People can travel long distance to seek traditional healing treatment. This may reflect the strength of the beliefs on traditional healing and not the modern psychiatric services and possibly greater faith in traditional treatment. Our results in this study is almost similar to what Campion and Bhugra found in India that the geographical distance from the psychiatric service of the traditional healers was not a barrier, which indicates that the physical need for relief of distress is of paramount importance. It is quite evident in our study that most of the patients are usually brought involuntary by their families or relatives for traditional treatment.

The perceived causes of the mental illness

Views about causation of the mental illness are strongly associated with help-seeking behavior. The findings of our study that, attribution of the mental illness to supernatural causes, was highly attributed with traditional healer consultation, it is quite evident in our study that, the majority of those who attributed their illness to evil spirit, jinn possession, Satan, or magic did not contacted the psychiatric services. These findings are in agreement with other previous studies. Razali, Khan, and Hasanah reported that the number of patients who believed in supernatural causes of their mental illness was significantly higher among those who had consulted traditional healers) than among those who had not consulted them and to show poor drug compliance. Saravanan, Jacob, Johnson, Prince, Bhugra, and David (2007) assessed qualitatively the explanatory models (EMs) of psychosis and their association with clinical variables in a representative sample of first episode patients with schizophrenia in South India they found that, the majority of patients (70%) considered spiritual and mystical factors as the cause of their predicament. Three factors were associated with holding of spiritual/mystical models (female sex, low education and visits to traditional healers). In a study of knowledge and practice of help-seeking for treatment of mental disorders in Pemba Island, Zanzibar, reported that 0.4% of the respondents attributed mental health problems to God’s power. In a study in Uganda had confirmed that supernatural causes of mental illness are perceived by many people in African communities. People seek treatment from traditional healers not only because the patients have common belief about the cause but also of the beliefs of the patients and their families on the effectiveness of the traditional healing interventions and treatment methods, this was quite evident in our study. A common view is that modern (western) treatments are effective in curing medical(physical) illness; but are powerless against black magic or supernatural causes agents; and consequently psychiatrist do not have the expertise to deal with supernatural powers. Some traditional healers are thought to be helped by jinn (supernatural being) in treating their patients and harbor spirits to chase away the evil spirit who intrudes on their territory said this close affinity between jinn, spirit possession and mental illness is not unique to Islam and similar beliefs are held in Hinduism, Buddhism and Judaism. MacLachlan, in Malawi suggested that traditional healers should be incorporated into ‘modern’ mental health services; because good mental health service should consider the beliefs of the patients it seeks to serve.

Conclusion and clinical implications

History of contact with psychiatric services is common among inpatient with mental disorders receiving treatment in the traditional healer’s centers in Sudan. Mental health professionals must be aware of the health beliefs model and the health-seeking behaviors when planning individualized patient care and treatment. To be able to understand the explanatory model and the attributed causes of the mental illness is very crucial for providing effective mental health services and possibly positional collaboration between psychiatrist and traditional healers for better management of patient with mental disorders. Future researchers are needed to explore how this collaboration can be worked out.

Study Strength and limitations

This is the first study conducted in the traditional healer’s setting in Sudan. There were only few studies conducted in the traditional healers setting worldwide. The study was conducted by a qualified research team and under the supervision of expert psychiatrists from University of Malaya, Malaysia. Our study is a cross-sectional study; and only provides association; we can not go beyond association. It is therefore important to be cautious in generalizing conclusions to all users of traditional healing services. The study relied on respondent’s recall of treatment process especially in regard to contact with psychiatric services over the past 12 months. There may be a recall bias; we tried to minimize this recall bias by cross-checking the information received from patients with the family members and close relatives accompanying the patients. Other factors we need to consider when interpreting these findings is that the respondents may be reluctant to admit the detailed experience of the traditional healing process or the respondent may tried to provide a socially desired answers to a team of researchers who are perceived as representing Western Medicine.

Future directions

Nevertheless, such a research has a useful role in helping to assess needs and resources for developing locally relevant mental health programmes. Future researches should focus more exclusively on the roles that traditional healers play in delivering mental health services. It is also necessary to carry out detailed assessment of the pathways to psychiatric care among psychiatric patients. A long term follow up studies are also needed with possibly larger sample size to address the possible explanation about the effects of traditional healing in treating mental illness. Future studies should also focus on methods of collaboration between traditional healers and mental health professionals for culturally accepted, combined and integrated management of the people with mental disorders.

References

- Abbo C, Okello ES, Musisi S, Waako P, Ekblad S (2012) Naturalistic outcome of treatment of psychosis by traditional healers in Jinja and Iganga districts, Eastern Uganda–a 3-and 6 months follow up. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 6: 1-11.

- Adewuya A, Makanjuola R (2009) Preferred treatment for mental illness among Southwestern Nigerians. Psychiatric Services 60:121-124.

- Ahmed IM, Bremer JJ, Magzoub MM, Nouri AM (1999) Characteristics of visitors to traditional healers in central Sudan. EMHJ-Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 5:79-85.

- Morsy AS, Soltan YA, Sallam SMA, Kreuzer M, Alencar SM, et al. (2015) Comparison of the in vitro efficiency of supplementary bee propolis extracts of different origin in enhancing the ruminal degradability of organic matter and mitigating the formation of methane. Animal Feed Science and Technology 199: 51–60.

- Soltan YA, Patra AK (2020) Bee propolis as a natural feed additive: Bioactive compounds and effects on ruminal fermentation pattern as well as productivity of ruminants. Indian Journalof Animal Health 59: 50–61.

- Papachroni D, Graikou K, Kosalec I, Damianakos H, Ingram V, et al. (2015) Phytochemical analysis and biological evaluation of selected african propolis samples from Cameroon and congo. Natural Product Communications 10: 67–70.

- Ozdal T, Sari-kaplan G, Mutlu-altundag E, Boyacioglu D (2018) Evaluation of Turkish propolis for its chemical composition , antioxidant capacity , anti- proliferative effect on several human breast cancer cell lines and proliferative effect on fibroblasts and mouse mesenchymal stem cell line. Journal of Apicultural Research 0:1–12.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Citation: Mia MH (2023) Exploring the Attitudes and Beliefs of the Relatives ofSudanese Patients with Mental Disorders: A Focus Group Study on Mental Illness,Traditional Healing and Modern Psychiatric Treatment. Int J Res Dev Pharm L Sci,9: 150.

Copyright: © 2023 Mia MH. This is an open-access article distributed under theterms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricteduse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author andsource are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 1125

- [From(publication date): 0-2023 - Apr 21, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 845

- PDF downloads: 280