Exploring Perceived Educational Needs of Primary Care Providers for Online Training and Education in Dementia

Received: 01-Mar-2023 / Manuscript No. dementia-23-92233 / Editor assigned: 04-Mar-2023 / PreQC No. dementia-23-92233 / Reviewed: 18-Mar-2023 / QC No. dementia-23-92233 / Revised: 24-Mar-2023 / Manuscript No. dementia-23-92233 / Published Date: 30-Mar-2023

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the perceived educational needs and preferences of primary care providers for training and education in dementia within an online environment.

Design: A prospective, qualitative research study.

Method: Participants were primary care providers purposively recruited currently licensed to practice in Ontario possessed a patient population with dementia, and willing to attend a focus group session and for one to one interview. A deductive content/thematic analysis was used to analyze the data. A total of 19 participants took part in the study across four focus groups (n=15) and four individual interviews (n=4).

Results: The study found that notion of credibility of information is critical to the learning process and highly valued by physicians. Credibility appears to overlap across the two constructs and the importance of credibility seems to link notions of perceived behaviour control with physicians’ subjective norms. Participants expressed an educational need for decision support, referring to learning that can support their ability to make clinical decisions. Participants expressed the value of educational tools such as technology resources, an online “evidence-based, physician-authored clinical decision support resource and so on. They also wanted to use other decision-making tools.

Conclusion: In conclusion, primary care providers have educational needs which may pose as facilitators and/or barriers to physician learning, eLearning and continuing medical education.

Introduction

Currently there are about 5.6 million Canadians living with dementia with an estimated nearly 1 million people diagnosed with dementia by 2031 [1]. A dementia diagnosis typically occurs in later stages of the disease when the symptoms are moderate or more severe, leading to hospitalization that may have been preventable if diagnosed earlier [2, 3]. Therefore, early identification and diagnosis of dementia is paramount because it can have a significant impact on healthcare risks, long term outcomes and healthcare experiences of this patient population and their caregivers [1, 3-5].

Primary care providers (PCPs) play a central role within dementia care and management since they are often the first point of contact with the health care system for a patient with dementia symptoms and are largely responsible for managing and coordinating dementia care [3,6]. Aminzadeh et al.’s [3] scoping review of the literature identified several specific primary care physician barriers, such as lack of knowledge, confidence, and diagnostic skills to identify dementia symptoms at an early stage of disease and lack of awareness of community supports or resources available for themselves, their patients and caregivers. Underlying systemic factors for these physician barriers may stem from a lack of appropriate post graduate family medicine training in dementia, but also a lack of effective continuing medical education in this area once in practice [7, 8].

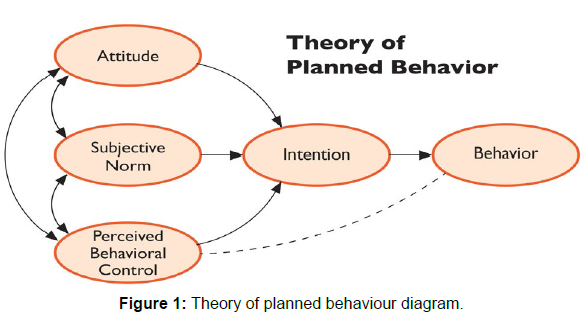

One potential solution to addressing the gap between the need for and availability of dementia training and education is the implementation of alternative educational approaches such as e-Learning [9-13]. To address the potential barriers and facilitators to e-Learning adoption, one very important consideration that can influence the usability and effectiveness of an e-Learning tool, is whether the design and continuing medical education (including postgraduate and continuing professional development) uses a theory informed approach [14]. Using a theoretical framework such as cognitive load theory, adult learning theory or the theory of planned behavior to facilitate the conceptualization of the design and features of an e-Learning platform for healthcare professionals may be helpful in addressing the learners needs and preferences for learning within an online environment [15-16]. The primary goal of this study was to carry out the initial user-needs phase to evaluate the perceived educational needs and preferences of primary care providers for training and education in dementia within an online environment.

Methods and Materials

Study design & recruitment

This study was a prospective, qualitative research study using focus groups to analyze physician learning, eLearning and continuing medical education regarding dementia training. The study was completed in collaboration with an academic research institute in Ontario.

Participants were primary care providers currently licensed to practice in Ontario (i.e. general practitioners, nurse practitioners), possessed a patient population with dementia, and willing to attend a focus group session (in person or video conferencing using Zoom (if necessary) for the allotted duration. Written and informed consent to the study were provided by each participant.

Purposive sampling was used. Recruitment emails and study were sent in a targeted manner directly from the investigators. Other recruitment strategies were used to promote the study by connecting with various not-for-profit organizations whose mission is to advance research in brain health, aging and Alzheimer’s. Twitter posts were also posted during the Family Medicine Forum Conference in Toronto to target the Investigators’ professional network on social media.

As a result, four focus groups were conducted with family physician participants in November 2018.

Survey instrument

The study aim was to conduct 4 focus group sessions (one 90 to 120-minute session per group) consisting of 3-4 study participants per focus group and one-to-one interviews with 4 providers. These numbers are in line with qualitative research guidelines to achieve saturation of themes in focus groups [17]. Azjen’s Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) constructs of Behavior of Interest, Attitude, Subjective Norms and Perceived Behavioral Control were used to develop and frame semi-structured questions for focus groups and interviews [18]. Study participants were also shown a few samples of medical related e-Learning platforms. Study participants were asked in general what they like and dislike about these platforms.

Sessions were audio-recorded and transcribed. Each focus group session was audio-recorded and later transcribed to written transcripts by a third party. All transcriptions were de-identified, and participants were coded with a unique subject identifier to facilitate analysis of discussions. Recruitment ended after thematic saturation was identified. Content analysis and literature review informed the initial codebook developed after analysis of the first two focus group transcripts. TPB constructs were used to provide structure to the analysis and to help categorize themes identified. The codebook was refined again after the fourth focus group. Interview participants were recruited by the researchers to discuss themes of interest in more detail. The codebook was refined again by each researcher based on an analysis of all transcripts including discussions about the definitions for each code and more specific inclusion/exclusion criteria for each code’s definition. Double coding was omitted for the interim but will be done in the future. Research Ethics Board (REB) approval was obtained from the host institution and Ryerson’s REB (approval reference number: 2018-347).

Data analysis

A deductive content/thematic analysis was used to analyze the data [19]. The Theory of Planned Behaviour was also used to inform and develop a set of a priori codes prior to data analysis, based on a literature review on the topic of physician learning, eLearning and continuing medical education [18]. Since a deductive approach was used, it was deemed appropriate to start off with a set of codes prior to analysis, and additional themes that emerged from the data would be identified. These codes were developed twice, first by the student investigator, then co-revised during an analytic discussion with all the investigators after reviewing the transcript. Refinements included discussions about the definitions for each code and more specific inclusion/exclusion criteria for each code’s definition. Double coding was omitted for the interim but will be done in future. Audio-recordings were sent to a third-party contractor to be transcribed. Appropriate measures were used to ensure that the files were transferred using secure file transfer service via email. The files were password protected as an additional security measure and the written transcript was de-identified for additional privacy protection. The codes were used to qualitatively analyze the four focus group transcripts. An attempt was made to label all comments within the transcripts. The codes were revisited and revised during a second analysis of the focus group data. An external third coder was brought in to solve any discrepancies.

Theoretical framework

Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behaviour can be utilized as a framework to help guide the design of this study [18]. This theory was selected based on its recent use and successful application to questionnaire development in a study investigating general practitioners’ intention to participate in e-Learning programs in CME [16]. According to the Theory of Planned Behavior, intentions (“a person’s readiness to perform a given behavior”) can be a good indicator for predicting behaviour [18]. Positive intentions towards a specific behavior is more likely when their beliefs (made up of their attitudes towards the behaviour, subjective norms and perceived behavioural controls) are also positive [18]. The Theory of Planned Behaviour was utilized to frame the focus group questions to uncover primary care provider attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control with respect to learning in an online environment for dementia training and education (i.e. the latter being the behavior of interest). This theory also facilitates the factors that may promote or discourage intentions and motivations to use e-Learning for continuing medical education in this context.

Results

A total of 19 participants took part in the study across four focus groups (n=15) and four individual interviews (n=4). Six additional primary care providers had expressed interest in the study, but due to clinic constraints and scheduling logistics, they were not able to attend the scheduled sessions. Sessions moved forward despite the limited number of participants at each session.

Table 1 represents the basic demographic information of the study participants which is presented here for descriptive purposes. All sets of participants are from academic family health teams in Toronto, Ontario and Kingston, Ontario. One physician participant is a locum doctor who floats between the hospital and the community (walk-in clinic) and therefore does not have a permanent roster of patients.

| Gender: | 5 Male; 14 Female |

|---|---|

| Age range: | 31 - 66 years old |

| Years in medical practice: | 4 – 38 years |

| Estimated total size of practice: | 600 – 1100 patients (1 locum physician has no roster of own patients) |

| Estimated number of dementia patients in practice: | 5 - 50+ patients |

Table 1: Demographic Information.

The Theory of Planned Behaviour was used to structure the semistructured focus group questions and to conceptualize the codes used for the data analysis phase of the study (see [Figure 1] in appendix A). More specifically, the theory provides a framework to help analyze primary care providers’ underlying attitude towards the perceived value of learning, their subjective norms in relation to others’ expectations and their perceived behavioural (control) factors that may have an influence on their learning. Together, these 3 theoretical constructs shape the primary care providers’ intentions towards engaging in learning in general and specifically in an online environment in the primary care setting for dementia care. A content analysis of the study transcripts led to several study findings.

(Attitude towards) perceived value of learning

Participant attitudes towards the perceived value of learning is the first theoretical construct used to conceptualize the study data into themes. This construct has been defined as “Respondents reflections on the value of continued learning for their professional and personal lives.” Participants expressed educational needs that were categorized according to five themes. These themes have been listed and defined in [Table 2].

Decision support (educational tools and peer connections)

Participants expressed an educational need for decision support, referring to learning that can support their ability to make clinical decisions (See Table 2, 1.1.1). Primary care providers expressed what they highly value in the learning process and are considered important to how they carry out their work. Decision support is divided into two sub-themes representing both 1) educational tools and 2) peer connections used to support their clinical decision-making process.

| Description | Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria | Examples from focus group discussions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Perceived value of learning | Respondents’ reflections on the value of continued learning for their professional and personal lives | ||

| 1.1 Decision support | References to learning that can support their ability to make clinical decisions | Includes references to educational tools or people | |

| 1.1.1 Educational Tools | References to educational tools that can support their ability to make clinical decisions | Includes references to paper based or technology resources (real or imagined) used as a tool to support/facilitate clinical decision making | “We don't know what’s going to happen a year from now – what the LHINs are going to look like, what other things are going to look like. You know, 6 months, 12 months from now. So where it said, okay, this patient…if this was something modifiable…you could enter even the geographic…the postal code of the patient, and it gave you resources like SPRINT or something that the patient or caregiver could access. That’s super valuable.” |

| 1.1.2 Peer connections | References to peers/ Peer connections to support their ability to make clinical decisions | Includes references to medical students, residents, fellows or specialists who are used as sounding boards or as a medium to facilitate clinical decision making | "I have a patient who had bilateral hip replacement and spinal stenosis surgery. So, he got a BMD but it’s pretty much uninterpretable because there are no points of reference. So, she [the resident] took the information down to Women’s College, asked the specialists there how they would interpret that, and came back with the information." |

| 1.2 Applicable to practice | References to learning being relevant to their clinical practice | “For me the major challenge is when I’m dealing with my geriatric patients is the complexity. I find that it's harder for me to take the evidence or take the presentations and relate them back to my patients 100% of the time because the studies don’t…they don’t control for renal function, or they don’t control for heart failure. “ | |

| 1.3 Increase knowledge | References to learning to increase knowledge (more generally) | Includes references to knowledge acquisition but not references to efficiency of knowledge acquisition | “...you can ignore what you want to ignore. But if it's something interesting and new then you’re probably going to pay attention to it.” |

| 1.4 Evaluation | References to being evaluated on the content as a demonstration of learning | “If I go to this site because I want to learn about dementia, you don't have to test me afterwards.... If I go to it because I want to get two hours of CME credits, you better check that I actually did it and learned something. And then you must have some kind of assessment at the end. “ | |

| 1.5 Patient-provider communication | References to learning that is relevant for patient-provider communications | “I have this patient who’s in her 80s who consistently tells me that she requires her HRT for her menopause symptoms. Do you (the specialist) have any suggestions on how to relay to her that in her situation, the risks far outweigh the benefits? You know, the symptoms that she’s referring to are unlikely to be menopausal. Right?” |

Table 2: Codebook: Themes and examples identified for attitude towards perceived value of learning construct.

Participants expressed the value of educational tools such as technology resources that they currently use, such as Uptodate.com, an online “evidence-based, physician-authored clinical decision support resource” (www.uptodate.com). Paper-based medical decision support tools such as RxFiles (which comes in both book and online format) were also mentioned during the discussion. RxFiles is a resource used by clinicians to review and compare different drug products when determining what medication to give a patient (www.rxfiles.ca).

Participants also expressed the value of educational tools that are currently not available but would prove very useful to them. Participant X envisioned an ideal online decision support tool that would allow direct input of relevant patient variables, including postal code and it would provide information that could be used to facilitate care coordination and management of their patients (See [Table 2], 1.1.1). The potential value of such a tool was also reinforced by Participant A who suggested to the researchers:

“...create a module that really flows with choices as a decision tree. You can really get information that’s more pertinent to the question that you’re asking, right, because you can, … You could really get something that’s more valuable by building in the patient variables…I have an 82-year-old or a 96-year-old man who’s living with his wife. The wife is the primary caregiver, also elderly. You know, you could be building in a lot of the variables that would give you particular information.”

Participants also expressed the value of peer connections in helping to support their decision-making process. When there is ambiguity and uncertainty about a patient’s clinical picture, physicians are challenged in determining the next steps in a patient’s care. This was demonstrated by Participant A who referred to a specific patient case where the participant’s medical resident took the initiative to obtain feedback from a specialist at another hospital where the resident was also doing a medical rotation (See Table 2, 1.1.2).While traditional methods of using a specialist for a formal consult is likely the standard for many physicians, primary care providers clearly find value in information seeking behaviour strategies that can facilitate and potentially speed up their clinical decision-making process.

Applicable to practice – Primary care providers expressed the need for learning to be applicable to their clinical practice (See Table 2, 1.2). Participant B indicated that learning needs to be relevant for specific patient cases in their care (See Table 2, 1.2). Participant Y shared a similar sentiment in terms of learning being applicable to practice, but in relation to the wider population they care for:

“...in terms of the modules… I mean I do use the Toward Optimized Practice guidelines out of Alberta. They have… I mean that’s great because it’s Canadian centric and relevant to long term care.... they’re one of the few Canadian resources that actually address the long-term care setting. Because the long-term care setting in the States is completely different than it is here.”

Participants mentioned the learning opportunities that are worthwhile attending such as rounds, which take place in-hospital. At these sessions, topics are usually relevant to their practice whereas, CME conferences and some educational modules are not necessarily on topics that are relevant to their clinical practice.

Other themes

Several other themes emerged from the data with respect to value of learning that increases knowledge, value of evaluation of knowledge as a demonstration of the learning and value of learning’s role in patient provider communications. Examples of these themes can be found in Table 2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5.

Subjective norms

Subjective Norms is the second theoretical construct used to conceptualize the study data and is defined as “Respondents beliefs about expectations in relation to others.” This construct refers to the perceived social pressure that physicians experience to engage in learning behaviours in relation to others’ expectations. Six thematic categories reflecting these expectations, including the self as a separate entity, are listed, and defined in [Table 3].

Patient and family caregiver expectations

One major theme identified in the data is how physicians’ beliefs about patient expectations might shape their learning behaviours. This is evident in Participant X’s comments regarding remaining updated on relevant healthcare media stories (See Table 3, 2.1). Family/ caregiver expectations about a patient’s care can also play a role in shaping physician learning behaviours and may be the same or differ from patient expectations. (See Table 3, 2.2).

Peers, regulatory college, and accepted standards expectations

Peer expectations (especially the specialists) could potentially influence another physician’s clinical decisions. (See Table 3., 2.3) There are also top-down pressures from the Regulatory Colleges such as the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons because of CME yearly requirements mandated by the colleges. (See Table 3, 2.4) Additionally, expectations are laid out in the various accepted standards that physicians are expected to conform with. These accepted standards refer to evidence-based guidelines or the gold standard in terms of care and can influence physician learning behaviours. (See Table 3, 2.5).

Personal expectations

Finally, participants have high self-expectations regarding their own learning behaviours. Participant A expressed how much pressure there is to conform to the gold standard (See Table 3, 2.6). In addition to matching the standard, the fear, and feelings of self-worth of not matching up to your peers are intertwined and can create extra pressure.

| Description | Inclusion/Exclusion criteria | Examples from focus group discussions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2. Subjective Norms | Respondents’ beliefs about expectations in relation to others | ||

| 2.1 Patient | References to beliefs in relation to patient expectations | “I get a lot of my initial medical information from the Globe and Mail, which I read religiously. And then I go and look up the articles that are being quoted. But it also tells me what some patients might come in and ask about. Because if they’re reading… Or if it’s in the Globe and Mail, it's on the CBC, you know, it's in the media. So, I feel like I need to know when people come in and say, “Well, what about vitamin D, is it useful or isn’t it?” I’m going to have to be ready to answer that.” | |

| 2.2 Family/Caregiver | References to beliefs in relation to patient's family/caregiver expectations | “I find that with my patients with dementia the most challenging thing is the fluctuation and the day-to-day functioning, and how to get the family support in the environment that they want them to be in.” | |

| 2.3 Personal | References to beliefs regarding self-expectations | "I think one of the biggest fears for physicians is you fall behind or you’re doing things that aren’t obsolete but you’re just not using standard practice right..." | |

| 2.4 Peers | References to beliefs in relation to peer expectations | Includes medical students, residents, fellows as peers; also includes references to peers as authors of medical sources of knowledge | “And then the cardiologist will tell them that their blood pressure needs to be at 130 on 80. And meanwhile I’m leaving them at 150 because I’m worried about their fall risk.” |

| 2.5 Regulatory College | References to beliefs in relation to Regulatory College expectations | “… we’re mandated to get CME credits, right. Like my inherent way of learning is not exactly the way that the profession mandates when to do it, right.” | |

| 2.6 Accepted standards | References to beliefs in relation to accepted standards | Includes references to gold standard expectations and evidence-based guidelines | “The gold standard is almost like intimidating because it’s like, you know, never use medications, never this, never that. But it’s not realistic sometimes.” |

Table 3: Codebook: Themes and examples identified for subjective norms construct.

Perceived behavioural control

Perceived Behavioural Control is the third theoretical construct used to conceptualize the data into themes (See Table 4). This construct has been defined as “Respondents beliefs about control factors that influence learning.” Ten themes emerged from the data in relation to this construct.

Sources of learning

A behavioural control factor that can influence physician learning is the source of learning. This thematic category was further divided into 5 sub-themes to separate the various types of sources of learning and represents a variety of learning environments that physicians may be exposed to (See Table 4, 3.1). This theme demonstrates that physicians can update their skills and knowledge in a diverse number of ways, and online environments such as uptodate.com or online selflearning platforms are only one avenue for online continuing medical education. A distinction was made between in-person formal sources versus in-person informal sources to separate out the more traditional lecture-based style of learning (e.g., conferences, seminars, and rounds) that physicians are accustomed. Alternatively, informal in-person social gatherings such as communities of practice or journal clubs are usually a small group of colleagues gathering to discuss a topic and/or related case studies.

Flexibility

Another major theme identified in the data is the notion of the flexibility of learning. References to this flexibility speak to the flexibility of when, how and what physicians can learn. While physicians can update their medical skills and knowledge through a wide variety of sources of learning, not all physicians share the same learning style or learning preferences, nor do they value them in the same way. The need for learning to be flexible is acknowledged by Participant X:

“I was dead set against the whole idea of online learning. And then I got arm-twisted into doing this course. And I am really sold on it now. You can go at your own pace, it can be made interactive while you’re sitting in your pajamas, you know, in your bedroom or whatever.”

And Participant Y:

“I mean I want to go and pick my knowledge, right. I want to pick and choose. I don’t want to necessarily… You know, on a day-to-day basis, I don’t necessarily want it presented to me because that just takes time and it’s inefficient.”

Time

Time, with respect to the participant’s own time and scheduling of his/her time, was considered a control factor in influencing learning behaviours:

“I don’t use these, … the podcasts, right…It just doesn’t fit into my life. I mean I walk to work…I think you just must be the type of person that learns by listening and that.”

The same participant reinforced the limitations of time in his life for certain types of learning activities:

“For me to find an hour of time to sit and watch a thing on dementia, I’m not going to do that…”

Credibility

The notion of credibility in the learning source may influence physicians’ willingness to engage with the learning source. Participants expressed varying opinions about specific third parties and the level of credibility they attribute to each in developing and/or disseminating medical knowledge. To one participant, credibility of a source is “a trusted sort of authoritative place.” This is exemplified in this exchange between the focus group facilitator and a participant:

Q: “What makes something trusted for you?”

A: “…the biggest thing would be an association with a university.”

Q: “But if it was funded by other sources, by other external parties…”

A: “If it’s industry then I have issues with that…I think it’s the

influence of companies on determining… You know, especially around guidelines and that, I don’t agree with…I don’t think they should be part of that…. I would look at who wrote it. I wouldn’t discount it because it was from the government. Whereas I would be very likely to discount an industry funded guideline, or one that didn’t declare what the source of the funding was. Because I notice that. “

Other themes

Several other themes emerged which relate to control factors that influence learning behaviours. These themes relate to type of ‘work environment’ the ‘Cost’ of learning, ‘Efficiency’ of learning in terms of acquiring the information, ‘Learning Satisfaction’ and Motivation. Example text from the focus group discussions supporting these themes can be found in [Table 4].

Discussion

This study investigated the educational needs for primary care providers for dementia training and education in an online environment. As shown in Table 2, 3, and 4, there are some critical aspects of physician learning which can highly influence physician’s willingness to engage in a learning process. Despite the limited data, the data seems to reveal that there are learning tensions that create conflicts between some of the themes identified.

It is clear from the study findings that the notion of credibility of information is critical to the learning process and highly valued by physicians. Credibility appears to overlap across the two constructs and the importance of credibility seems to link notions of perceived behaviour control with physicians’ subjective norms. Credibility references in the study data demonstrate that it is not only a control factor in learning but is also a characteristic of the expectations that physicians have of the authors of such information, as highlighted by other studies [20]. This overlap is unsurprising as evaluating credibility and the possibility of inherent bias in the medical information being presented is important to the practice of medicine due to patient implications in the application of knowledge [21].

There appears to be a learning tension experienced by providers in applying the standards of education with the clinical applicability of information, particularly for complex patients like dementia patients. Though the physician profession has evolved from a paternalistic approach to a much more patient-centric one, the values and interests of the patient and the involvement of their family/caregivers in the care process can influence the care plan chosen by the physician [3]. Internal conflicts can be experienced by physicians regarding patient care plans when expectations differ between the patient, family/caregiver, and the standards set out in evidence-based guidelines. In a study on family physician perspectives, physicians expressed concerns about shifting the burden of dementia care into the community, particularly for the home and family [22]. There may be differing expectations of the quality of care and community support by the patient and the family or caregiver. Simultaneously, physicians may not be aware of or choose to adhere to evidence based guidelines that ‘recommend’ medicating for specific types of dementia [20,23]. Physicians are then challenged with reconciling different expectations and internal conflicts in their clinical decision-making.

There is an additional tension between self-expectations and clinical applicability where, as shown in Yaffe et al’s dementia care study, some physicians, burdened by their time constraints and clinical demands, expressed it is not their role to learn about the community supports available to their patients and alternatively, make referrals to a central community organization [22]. In this event, a physician’s own self expectations about what they learn or are willing to learn, may conflict with their personal expectations about what it means to be “a good quality professional practitioner” [24]. The importance of keeping up to date with medical knowledge and skills to ensure that patients are receiving the gold standard seems obvious; however, selfdirected learning and continuing medical education is also very much a “personal process,” which can influence whether physicians complete an e-learning program even in a highly clinically applicable topic such as evidence-based medicine [25]. It would be worthwhile exploring this ‘personal process’ concept in more depth in future with other study participants, as it may provide additional insights on subjective norms in relation to beliefs and expectations about personal autonomy and self-discipline in continuing medical education, which has not been discussed in the study findings.

A learning tension experienced by providers with the perceived behavioural constructs of flexibility and time and an overlap with the perceived value construct of clinical applicability is suggested. Evident in the study results, a range of perceived behavioural control factors can differentially influence physicians’ learning behaviours. Flexibility and time were major themes often commented on throughout the focus group discussions and are common concepts in the realm of medical learning and eLearning. Improving the quality of learning experiences for medical learners such as physicians, requires the recognition of the added time commitment required for continuing medical education on top of daily clinical demands. In some cases, flexibility and time are sometimes inter-related concepts within the confines of physicians’ personal time versus clinical time for continuing education opportunities. Positive attitudes towards medical eLearning include flexibility as a benefit as it can reduce the impact on personal and work time commitments [26]. In contrast, negative attitudes towards eLearning have also been found where limited time availability and inflexibility of the learning approach were cited as reasons why physicians differed in their completion rates of an eLearning program on evidence-based medicine [25].

Online platforms can address the highlighted tensions discussed above, by offering 1) potential flexibility, 2) tailoring to clinical needs and 3) providing access to credible sources. Regarding flexibility, the options that can be made for an online medical education learning environment are virtually endless and can be varied in terms of types of sources, instructional designs, and methods to meet various learner styles and preferences [27-29]. This potential flexibility can increase access to continuing education opportunities via eLearning for practitioners in rural locations where face-to-face continuing education opportunities may be more limited. This is especially pertinent for nurse practitioners who are sometimes the main primary care provider in rural settings [30]. An online medical education learning environment can additionally be catered to clinical needs and can be achieved by ensuring that the online content is current, constantly updated, and easy to navigate and retrieve the information that the user is seeking, as exemplified in the popularity and regular use of uptodate.com as a decision support tool. As suggested by participants, acquiring information more quickly than traditional pathways can be highly valuable for physicians with busy schedules. Additionally, creating a technology solution like a decision tree format may be a valuable way to both improve the quality of care and management of patients while promoting adherence to best practice guidelines for patient care. Accessibility to credible sources can also be addressed in an online learning platform. While an online environment may address other learning tensions, if the information is not free of bias and evidence-based, it is highly unlikely that providers will be interested in the information being presented.

Participants mentioned the value in synchronous communication methods, however also recognized that they do not have time for real time, team-oriented messaging apps like Slack (www.slack.com). Instead, they suggested integrating something similar in technology that they already use on a daily basis such as their citrix dashboard, for when they email colleagues from home.

Limitations

The study had a few limitations to be considered when interpreting the findings. All participants were physicians affiliated with academic hospitals which are not representative of the target population that the eLearning platform will be designed for. A major study limitation was the recruitment challenges experienced during the study. While extensive efforts were made to reach out to a variety of different networks, it was very difficult to recruit primary care providers for a focus group study, which was reflected in another study [31]. One physician expressed interest in the study but only if it was a survey, as a focus group study was not feasible. It has been suggested that primary care providers would probably need at least 6 weeks’ notice to schedule a focus group session into their calendar. Other challenges which impacted the recruitment ability within a short timeframe, is that recruitment of physicians from other hospitals, medical residents, and study conduct at non-study sites generally require additional ethics approval. This limitation impacted the ability to reach out to a higher number of potential participants.

Conclusion

This study’s findings demonstrate that primary care providers have educational needs which may pose as facilitators and/or barriers to physician learning, eLearning and continuing medical education. A complex number of considerations and overlapping learning tensions that are critical to any organization or person interested in creating continuing medical education opportunities were highlighted. The relationship of these themes and underlying perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs, need to be more deeply explored as it may provide additional insights and a novel theoretical finding regarding the underlying factors that promote or discourage physician learning, which may lead to improved solutions for promoting and enhancing physician learning environments.

Appendices

Appendix A

[Figure 1]

Appendix B

Participant Information Form

Participant ID: _____

Today’s Date: ________

1. Gender

o Male

o Female

o Other (specifying is optional): _____

o Prefer not to say

2. Age (in years): ____

3. Years in medical practice: ____

4. Structure of Primary Care Organization:

o Solo practice

o Family Health Organization

o Family Health Team

o Community Health Center

o Other (specify): ____________

5. Estimated total size of your practice (i.e., total number of rostered or registered patients): _______

6. Estimated number of dementia patients in practice: _______

7. Full postal code of practice: ______

(This will only be used to generalize the community that you practice within)

8. Estimated number of hours in a month that you spend on dementia care and management: _____

9. Do you have Care of the Elderly Certification?

o Yes

o No

10. Does your primary care organization currently participate in any primary care dementia programs such as Primary Care Memory Clinics?

o No

o Yes (please describe): _______________________________ ________________

_____________________________________________________ _____________

_____________________________________________________ _____________

11. Estimated time spent in online continuing medical education/continuing professional development activities versus inperson/ live events (i.e. hours per month): _________

12. How comfortable are you in using computers to access the internet?

o Very uncomfortable

o Uncomfortable

o Neither uncomfortable or comfortable

o Comfortable

o Very comfortable

13. a) Have you previously used online learning tools/modules for continuing medical education?

o Yes

o No

o Can’t recall

b) If you answered yes to the above (Q13a), how do you prefer to access to online learning tools/modules for continuing medical education?

o Internet browser

o Smart phone application

o No preference

c) If you answered yes to the above (Q13a), please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: “My experience with online learning was a good one.”

o Strongly disagree

o Disagree

o Slightly disagree

o Slightly agree

o Agree

o Strongly agree

Please provide a couple of reasons for your answer to Q13c.

_____________________________________________________ ________________ _____________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ _____________________________

Appendix C

Focus group semi-structured interview guide

Introduction

• Introduce self and project, quick overview of consent items

• Roundtable introductions (name, role, whether they’ve used online tools before)

Section 1

General (intention and behavior of interest):

In this first part we’re going to talk about how you update your skills and knowledge, particularly thinking about CME credits and other accredited learning.

1. How do you currently update your skills and knowledge?

a. Probe: Talk about why you have used eLearning before (OR alternatively, tell me why you haven’t used eLearning before.)

b. Probe: How might your responses change if you’re thinking about learning about dementia, assessment, care and management specifically?

c. Probe: Have the Canadian Best Practice Guidelines in Dementia care and management been useful for you?

Attitude (towards action):

We talked a bit about online learning so let’s dig into that a bit.

2. What advantages do you see in online learning?

a. Probe: Does the flexibility in scheduling learning interest you?

b. Probe: Does the novelty of instructional methods interest you (such that it can fit with your learning style?)

c. Probe: Does the online assessment and documentation aspect interest you? (e.g. record of what has been reviewed, online certificates of completion, online record keeping of CME credits, etc)

3. What about disadvantages?

a. Probe: Does the social isolation factor concern you?

b. Probe: Does the potential for technical problems concern you?

c. Probe: Does the potential costs concern you (e.g. if there are subscription fees)?

4. How, if at all, do your reflections change if you’re thinking about learning about dementia assessment, care and management?

a. Probe: What is unique about the dementia patient population that may make you feel different about online dementia training and education compared to online training and education for other illnesses?

Subjective norms:

We know you have lots of options when it comes to updating your skills, learning and gaining CME credits,

5. What are reasons why you might feel that e-Learning is an important tool for your CME? (Or alternatively, why is it not that important to you).

a. Probe: How might your response change if you’re thinking about learning about dementia, assessment, care and management specifically?

b. Probe: Has any past online educational experiences (if any), led you to make changes in your practice?

Perceived behavioral control

6. What would drive you to use an online platform over traditional methods such as attending a conference or an in-person seminar?

a. Probe: Do organizational resources play a role?

b. Probe: Do the expectations of your organization or accrediting bodies play a role?

Section 2

Now that we’ve figured out a bit regarding what works and what doesn’t for us when thinking about online learning, let’s take a look at some online tools currently available and reflect on them.

[Hand out tools to group]. Take a few minutes to look these over.

7. What do you like about these tools?

8. What don’t you like?

9. What do you think is missing?

References

- Alzheimer Society of Canada (2022) Dementia numbers in Canada. Alzheimer Society of Canada.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information [CIHI] (2011) Health Care in Canada, 2011 A Focus on Seniors and Aging. CIHI, 162.

- Aminzadeh F, Molnar FJ, Dalziel WB, Ayotte D (2012) A Review of Barriers and Enablers to Diagnosis and Management of Persons with Dementia in Primary Care. Can Geriatr J 15: 85-94.

- Adler G, Lawrence BM, Ounpraseuth ST, Asghar-Ali AA (2015) A Survey on Dementia Training Needs Among Staff at Community-Based Outpatient Clinics. Educational Gerontology 41: 903–915.

- Warrick N, Prorok JC, Seitz D (2018) Care of community-dwelling older adults with dementia and their caregivers. CMAJ 190: E794–E799.

- Allen M, Ferrier S, Sargeant J, Loney E, Bethune G, et al. (2005) Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: An organizational approach to identifying and addressing practices and learning needs of family physicians. Educational Gerontology 31: 521–539.

- Prorok JC, Stolee P, Cooke M, McAiney CA, Lee L (2015) Evaluation of a Dementia Education Program for Family Medicine Residents. Can Geriatr J 18:57-64.

- Surr CA, Gates C, Irving D, Oyebode J, Smith SJ, et al. (2017) Effective Dementia Education and Training for the Health and Social Care Workforce: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Rev Educ Res 87: 966-1002.

- Cook DA, Levinson AJ, Garside S, Dupras DM, Erwin PJ, et al. (2008) Internet-based learning in the health professions. JAMA 300: 1181–1196.

- Ruiz JG, Mintzer MJ, Leipzig RM (2006) The Impact of E-Learning in Medical Education. Acad Med 81(3):207-212.

- Reeves S, Fletcher S, McLoughlin C, Yim A, Patel KD (2017) Interprofessional online learning for primary healthcare: findings from a scoping review. BMJ Open 7: e016872.

- Abdelaziz M, Samer Kamel S, Karam O, Abdelrahman (2011) Evaluation of E-learning program versus traditional lecture instruction for undergraduate nursing students in a faculty of nursing. Teaching and Learning in Nursing 6: 50 – 58.

- Vaona A, Banzi R, Kwag KH, Rigon G, Cereda D, Pecoraro V, Moja L (2018) E-learning for health professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1: Cd011736.

- Hodges BD, Kuper A (2012) Theory and practice in the design and conduct of graduate medical education. Academic Medicine 87(1), 25–33.

- Mayes T, De Freitas S (2013) Review of e-learning theories, frameworks, and models.

- Hadadgar A, Changiz T, Masiello I, Dehghani Z, Mirshahzadeh N, et al. (2016) Applicability of the theory of planned behavior in explaining the general practitioners eLearning use in continuing medical education. BMC Med Educ 16: 215.

- Babbie E, Benaquisto L (2014) Fundamentals of Social Research Methods (3rd Cdn.). Toronto: Nelson Education Ltd.

- Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Orgnizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50: 179–211.

- Alhojailan MI (2012) Thematic analysis: a critical review of its process and evaluation. West East Journal of Social Sciences 1: 39 – 47.

- Moore A, Lee L, Bergman H, Patterson C, Bedella I (2014) Fourth Canadian Consensus Conference on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementia.

- Young KJ, Kim JJ, Yeung G, Sit C, Tobe SW (2011) Physician Preferences for Accredited Online Continuing Medical Education. J Contin Educ Health Prof 31: 241–246.

- Yaffe MJ, Orzeck P, Barylak L (2008) Family physicians’ perspectives on care of dementia patients and family caregivers. Can Fam Physician 54: 1008–1015.

- Gauthier S, Patterson C, Chertkow H, Gordon M, Herrmann N, et al. (2012) Recommendations of the 4th Canadian Consensus Conference on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Dementia (CCCDTD4). Canadian Geriatrics Journal : CGJ 15: 120–126.

- Brace-Govan J, Gabbott M (2004) General Practitioners and Online Continuing Professional Education : Projected Understandings Web-Based Education as Innovation and Continuing Medical Education. Educational Technology and Society 7: 51–62.

- Gagnon M, Légaré F, Labrecque M, Frémont P, Cauchon M, Desmartis M (2007) Perceived barriers to completing an e-learning program on evidence-based medicine. Informatics in Primary Care, 15: 83–91.

- Docherty A, Sandhu H (2006) Student-perceived barriers and facilitators to e-learning in continuing professional development in primary care. Educ Prim Care 17: 343-353.

- Cook DA, Garside S, Levinson AJ, Dupras DM, Montori VM (2010) what do we mean by web-based learning? A systematic review of the variability of interventions. Med Educ 44: 765–774.

- Cook DA, Levinson Anthony JMDMs, Garside Sarah MDP, Dupras Denise MMDP, Erwin PJM, et al. (2010) Instructional Design Variations in Internet-Based Learning for Health Professions Education: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Academic Medicine 85: 909–922.

- Cook DA, Levinson AJ, Garside S (2010) Time and learning efficiency in Internet-based learning: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Health Sci Educ 15: 755–770.

- Baxter P, DiCenso A, Donald F, Martin-Misener, R., Opsteen J, et al. (2013) Continuing education for primary health care nurse practitioners in Ontario, Canada. Nurse Educ Today 33: 353–357.

- Johnston S, Liddy C, Hogg W, Donskov M, Russell G, et al. (2010) Barriers and facilitators to recruitment of physicians and practices for primary care health services research at one centre. BMC Med Res Methodol 10:1-109.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Citation: Nippak P, Pirrie L, Steele-Gray C, Seitz D, Coughlan D, et al. (2023) Exploring Perceived Educational Needs of Primary Care Providers for Online Training and Education in Dementia. J Dement 7: 151.

Copyright: © 2023 Nippak P. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Conferences

42nd Global Conference on Nursing Care & Patient Safety

Toronto, CanadaRecommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 2050

- [From(publication date): 0-2023 - Feb 23, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1904

- PDF downloads: 146