Research Article Open Access

Exploring Legitimacy and Authority in the Construction of Truth Regarding Personal Experiences of Drug Use

N Kiepek*

School of Occupational Therapy, Dalhousie University, Ontario, Canada

- Corresponding Author:

- N Kiepek

Assistant Professor, School of Occupational Therapy

Dalhousie University, Ontario Canada

Tel: 902-494-2609

E-mail: niki.kiepek@gmail.com

Received date: Feb 17, 2016; Accepted date: Mar 26, 2016; Published date: Apr 03, 2016

Citation: Kiepek N (2016) Exploring Legitimacy and Authority in the Construction of Truth Regarding Personal Experiences of Drug Use. J Addict Res Ther 7:273. doi:10.4172/2155-6105.1000273

Copyright: © 2016 Kiepek N. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Addiction Research & Therapy

Abstract

Objectives: This research explored drug use from the perspectives of individuals who recreationally used one or more substances on a daily basis and had never attended addiction-related counselling or a mutual support group. The purpose of the research was to identify the ways that narrative accounts were discursively structured to enact, confirm, legitimate, reproduce, or challenge the concept of addiction.

Methods: The methodology involved a critical analysis of discourse, drawing on personal accounts of drug use that were elicited using discursive narrative strategies.

Results: The finding demonstrated that narrative accounts were constructed in relation to dominant discourses in the North American context. Efforts to refute dominant discourses can be viewed as a response to risks associated with self-disclosure of subjugated positions. The findings presented in this paper pertain to the ways in which research participants adopted indirect discursive practices that challenged distinctions between legal, socially sanctioned drug use (namely, medications) and illegal, socially unsanctioned drug use. Drawing in particular discursive strategies, the research participants blur the lines between categorization of drugs and drug-related practices as healthy or unhealthy, moral or immoral, socially acceptable or socially acceptable. Overall, the findings demonstrate that the research participants challenged dominant discourses that position illicit drug use and distribution as being socially unacceptable.

Conclusion: This research uncovers discursive practices of power, authority, legitimacy, dominance, and inequality in relation to drug-related policy, research, and education. The findings offer an alternative interpretation to narrative accounts that might otherwise be interpreted as ego defense mechanisms.

Keywords

Substance use; Critical discourse analysis; Recontextualization; Narrative interview; Discursive practices; Denial

Glossary

Critical discourse analysis: Critical discourse analysis is a systematic method to evaluate the ways in which language acts as a relational process that simultaneously establishes and maintains social hierarchies, sources of authority, and forms of individual and population regulation.

Recontextualization: Recontextualization is a process through which meanings are transformed when language is selectively appropriated from one field to another. Transformation of meaning can occur when meanings are taken out of their contexts (decontextualization) and meaning is put into a new context (recontextualization).

Discursive practices: The ways in which language simultaneously provides access to subjective, situated experiences and constructs knowledge.

Flipping the script: Flipping the script is a colloquial term, used in hip hop and rap. It is the act of strategically appropriating words and concepts and altering the associated meanings as a way to assert a change in dominant ways of thinking, acting, and being.

Ego defense mechanisms: Defense mechanisms are concepts related to psychoanalytical theory, and described as unconscious processes that shield one’s self from a conscious awareness or knowledge of phenomena that may cause emotional discomfort. Defense mechanisms discussed in this article include denial, justification, rationalization, intellectualization, minimization, and neutralization.

Introduction

Sometimes author aint so sho who’s got ere a right to say when a man is crazy and when he aint. Sometimes author think it aint none of us pure crazy and aint none of us pure sane until the balance of us talk him that-a-way. It’s like it aint so much what a fellow does, but it’s the way the majority of folks is looking at him when he is doing it....And author reckon they aint nothing else to do with him but what most folks say is right [1].

The purpose of the research project presented in this article was to explore drug use from the perspectives of individuals who recreationally used one or more substances on a daily basis. These individuals had never attended addiction-related counselling or a mutual support group, and had not been formally assessed regarding their substance use.

Research shows that the majority of individuals who meet the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, text revision (DSM- IV-TR) criteria for a lifetime diagnosis of substance abuse or substance dependence reduce or quit substance use without formal intervention [2,3]. Individuals who access addiction related services, or who are identified through the justice system, are more likely to meet the diagnostic criteria for a mental health disorder, a developmental delay, and to have fewer pre-existing socioeconomic resources [4-6]. Therefore, addiction research and policy that is based on the experiences of this population may not reflect the experiences of the majority of the population who use drugs.

It may be argued that, for many people, their narratives of substance use remain hidden and silenced. As stated by Robyn Warhol, “drug addicts are (perhaps) the last minority to be forced, legally, morally, and culturally, into the closet, without really having the option to come out” [7]. Being exposed as a person who uses drugs opens one to a host of potential negative consequences, such as child custody investigation, loss of employment or future opportunities, stigmatization from family, friends, and acquaintances, and legal charges. These consequences may be unrelated to the direct effects of the drug on the person, their performance, or their abilities. Therefore, in Canada, where this research was conducted, there are few forums where people can openly talk about drug use experiences that may differ from the dominant perspectives that shape policy, legislation, theory, service delivery, and education.

Compounding the potential for negative consequences associated with self-disclosure or exposure is the concept of denial, which dominates drug discourse throughout North America. The concept of denial is derived from Verleugnung, which can be translated as “disavowal” and was coined by Freud in 1924 as an ego defense mechanism [8]. In everyday practices, the term denial has been framed according to the acronym: D-E-N-I-A-L = Don’t Even Know I’m Lying [9]. The potential problem associated with the wide adoption of this concept among the public in North America is that is serves as a rhetorical device to discount any personal account or description of drug use that falls outside the dominant discourses. For example, when people asked about my doctoral research I explained that I was “interviewing people who used drugs on a daily basis and had never identified a reason or need to attend counseling.” The most frequent response was a nod and knowing smile, “Oh. They are in denial.” This interpretation came prior to having receiving any information about the person or the nature of drug use.

The concept of denial functions to give authority of interpretation to the listener and, in effect, discounts personal accounts by labelling them as erroneous. Other concepts that function in similar ways are justification, rationalization, intellectualization, minimization, and neutralization. This practice draws on psychoanalytic theories that assume the true meaning of client utterances are “yet-to-be-decided” by an authoritative figure [10]. Accordingly, in contemporary counselling, clients are positioned as knowable, malleable, and deferring (Guilfoyle). This means that it is expected that i) The counsellor can understand the situation and experiences of the client, ii) the client is able to change their ways of thinking, talking, and acting, and iii) the client is expected to defer the interpretation of their experience to an expert (Guilfoyle). This practice is particularly important in relation to addiction research that draws on research participants who have attended addiction-related counselling. Throughout the counseling process, clients learn the proper way to talk about their use of drugs and experiences and accurate ways of interpreting the experience. It is proposed that individuals who identify themselves as having an addiction “tell and retell their newly reconstituted life stories according to the grammatical and syntactical rules of disease and discourse that they have come to learn” [11].

To provide an example, when reviewing interviews conducted with a group of pharmacists who had attended Narcotics Anonymous, it was noted that the pharmacists adopted the discourse that is promulgated by NA and integrated it into their own styles of communication as pertained to personal life events [12]. Accordingly, the researchers questioned whose “voice” was being heard in these interviews.

Situating the research findings of the present study within a societal context where denial is a pervasive and dominant perspective is essential to understanding the findings from the analysis. The intention of the research project was to investigate i) the discursive practices enacted when individuals talk about their drug use, ii) what discourses shape personal understandings about drug use, and iii) how language is used to construct a conceptual understandings about drugs and drug use. The pervasiveness of denial as a concept in Canadian society impacts the perceived credibility of the research participants and the subsequent interpretations of the findings.

A critical analysis of discourse was implemented to analyse how the participants constructed personal accounts of drug use and how they affirmed and refuted aspects of dominant discourses. Discourse is a relational process through which concepts are talked about and truths constituted, ascribing appropriate ways of being and acting [13]. Discourse simultaneously establishes and maintains social hierarchies, sources of authority, and forms of individual and population regulation [14]. As posited by Foucault, a critical analysis of discourse involves developing an awareness of what is being spoken about, acknowledging the sources of the discourse, situating the positions that influence the discourse, and exploring the ways in which institutions shape and disseminate knowledge.

Certain discourses are attributed higher status, privilege, and legitimacy. Bakhtin [15] defined authoritative discourses and internally persuasive discourses as two processes through which this can occur. Authoritative discourse is historically bound and contributes to perceptions of legitimacy and status, such as religious dogma, scientific findings, and distinguished texts. Bakhtin proposed, “[t]he authoritative word demands that we acknowledge it, that we make it our own; it binds us.... It is therefore not a question of choosing it from among other possible discourses that are its equal. It is given” (p. 342). Authoritative discourse is considered to be inflexible, and one is required to either fully affirm it or fully refute it. Legal and medical discourses function as two of the dominant discourses pertain to drugs.

On the other hand, internally persuasive discourse is not simply interpreted “as is,” but can be freely and creatively adapted to novel situations. Internally persuasive discourses are influenced by multiple discourses that “struggle” with one another. Internally persuasive discourses are considered to be “unfinished,” affording opportunity to create new ways of understanding. This opens the possibility for discourse to be applied to new contexts, to contribute to the development new insights to the phenomenon, and generate new discourses.

The discursive practices of centripetal and centrifugal forces can further analyses of how ideological positions represented in language. Bakhtin believed that “no living word relates to its object in a singular way” (p. 276). Instead, he proposed that every utterance is constituted through both centripetal and centrifugal tendencies that can be identified through detailed analysis. Centripetal forces are historical and social processes that act towards the development of a unitary language and serves to centralise the ideological position represented by a word. This process is influenced by specific social groups in order to transcend the realities of heteroglossia, a term used to describe the multiple ideological positions represented through language. Opposing heteroglossia, centripetal forces act by “imposing specific limits to it, guaranteeing a certain maximum of mutual understanding and crystallizing into a real, although still relative, unity - the unity of the reigning conversational (everyday) and literary language, ‘correct language’ [15].

At the same time, centrifugal forces of language exist alongside centralised and unifying language, enacting processes of decentralisation and disunification. Bakhtin stated that, “Every concrete utterance of a speaking subject serves as a point where centrifugal as well as centripetal forces are brought to bear. The processes of centralization and decentralization, of unification and disunification intersect in the utterance”. At the same time, multiple, competing discourses may be present within an individual narrative account. Foucault drew attention to the presence of discourses of resistance and silent discourses. He affirmed that it is through analysis of the contradictions and tensions evident in social and individualised language that the meaning of a concept begins to take shape [14].

This paper will focus the analysis on the ways in which research participants adopted indirect discursive practices that challenged distinctions between legal, socially sanctioned drug use (namely, medications) and illegal, socially unsanctioned drug use. The discursive styles will be discussed in relation to the inherent risks experienced by directly refuting dominant discourses, which could potentially be interpreted as evidence of ego defense mechanisms.

It was not the intention to unveil or describe the true nature of drug use, but rather to investigate the ways in which stories can have political consequence. This is aligned with the position that “What matters is who has the power to name, to represent common sense, to create ‘official versions’, and to represent legitimate social worlds, while excluding other stories which might construct these things very differently” [16]. Accordingly, this research afforded an opportunity to explore drug use from a segment of the population who have largely been absent from discussions that inform policy and theory.

Methodology

The methodological approach integrated a blend of narrative and discursive methodologies. The data collection was informed by narrative methodology and the analysis was designed based on the principles of critical discourse analysis. The intent of the analysis was to examine “the way social power abuse, dominance and inequality are enacted produced and resisted by text and talk in the social and political context” though the use of language [17]. The purpose of the research and analysis was to identify the ways discourse was structured to enact, confirm, legitimate, reproduce, or challenge the concept of addiction. This form of analysis was recognized to have the potential to uncover issues of power, authority, legitimacy, dominance, and inequality.

To elicit narrative accounts of drug use, discursive interview strategies were implemented. The intention was to limit the role of the interviewer in directing the narrative and to provide opportunity for multiple voices and contradictory perspectives. To facilitate a context wherein inconsistencies and contradictions emerge, it is recommended that adequate interview length is available, avoiding a sense feeling rushed [18]. Questions were designed to guide a stream of consciousness interview and to elicit multiple discourses. Furthermore, to invite narratives about potentially emotional or contentious material, the interviewer conveyed a friendly, non-judgmental demeanor, drawing on reflective listening techniques.

Research interviews are viewed as inherently polyphonic, meaning that multiple voices, words, and discourses are embedded in the talk [19]. Narratives, according to this approach, are not anticipated to provide insight into a fixed, unitary, authentic self, but rather provide access to an understanding of the multiple discursive repertoires spoken by a person, in a particular setting. This facilitates an investigation as to “how language ‘makes’ people and produces social life” (Tanggaard).

In addition, narrative methodology is viewed as a means to “see how respondents in interviews impose order in the flow of experience to make sense of events and actions in their lives” [20]. This is based on the belief that narrative accounts provide a context where the process of retrospective meaning-making occurs, allowing opportunity to analyse how the accounts are organized and meaning conveyed [21]. By integrating a narrative discursive methodology, the methodology allows shifts towards an analysis of how language and discourses convey perceived meanings, where meaning is viewed as a constructed, relational process rather than an individual, subjective experience.

Study Design

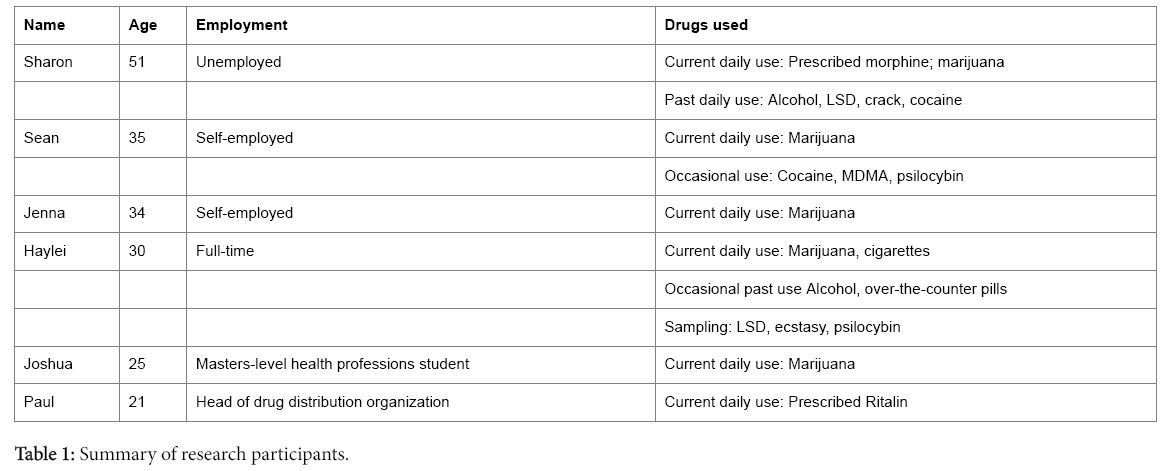

Six research participants in across Manitoba and Ontario were interviewed. The intention was to explore the intertextual nature of multiple discourses embedded within narrative accounts. Accordingly, six participants provided extensive data for analysis (Hill) [22]. Recruitment was conducted through informant sampling, poster advertisement at Western University, and a listing on Kijiji, a free, Internet-based classified advertising site. Using Kijiji, it was recorded that the advertisement was viewed by hundreds of people over a fourweek period.

The inclusion criteria were that the person be at least 18-years-old and self-report engagement in “the use of a psychoactive substance (i.e., opioid, hallucinogen) on an approximately daily frequency.” Exclusion criteria included having ever attended addiction counseling or a 12-step self-help group or having received a clinical assessment in relation to substance use. Interviews ranged from 90-300 minutes in length and were generally held in a public meeting area, such as a library. Participants engaged effectively in the interview process and were not asked whether they had recently used a substance or experiencing any withdrawal effects.

The semi-structured interview guide was designed to intentionally exclude questions that typically form a component of a health-related addiction assessment, such as history of use (amount used, frequency) and family of origin (historical use by family members). The interviewer adopted a neutral standpoint and avoided replying in a way that would convey interpretation or evaluation. Discursive strategies were implemented to elicit multiple discourses, such as asking about what someone else had said in relation to drug use, how the research participant would talk to a child about drug use, and who he or she considered a desired audience for their narrative. There was opportunity for the participant to provide clarification or correction while engaging with the interviewer and member checking was performed following analysis. The interviewer has advanced training and practice to establish neutral and non-judgmental interview contexts, to elicit elaboration, and to guide the interview to address all interview questions.

Research Participants

One question that is frequently asked in relation to the interviews is whether the research participants only disclosed the ‘good things’ about their drug use. This did not seem to be the case, and beyond that, the participants acknowledged the potential risk they were took by engaging in the interview. For example, Jenna expressed concern that formal disclosure of marijuana use might result in a mandatory reporting obligation from the interviewer to child protective services. Paul was a leading member of, in his words, “an organization,” which, in Canadian legal contexts, would be referred to as an “organized crime group.” He advised me that he had colleagues in the vicinity and throughout the interview he interspersed detailed personal information he had gathered about me prior to the meeting; a subtle reminder of his requirement for privacy. Joshua discussed his concerns that as a health professions student, if potential employers knew that he smoked marijuana everyday they would likely not consider him as a candidate for future jobs. Prior to the interview a friend had teased him that the interview could be a “set-up.” In the interview he said,

Joshua: It’s like, I n- I never thought it was a set-up, but like, for a second though I [chuckles] \Wh-what is it? What if it is a set-up?\ [laughing voice] \I just picture my world crumbling around me.\ [laughs] Oh. I’ll my-, I’ll just walk into the room with all my teachers, waiting.

A brief description of each participant is provided in Table 1. In summary, there were three men and three women who ranged in age from 21 to 51-years-old. Sharon used prescribed morphine to manage pain and smoked marijuana on a daily basis. She described that, unlike smoking marijuana, morphine interfered in her daily routines and performance of daily activities. In the past she used cocaine and LSD for years at a time. She also “cooked” and sold crack at one point in her life. Sean was married and had two children. He explained that marijuana helped to “motivate” him and appreciate certain activities more, such as taking his son for a bike ride. He drank alcohol and used MDMA (3,4- methylenedioxymethamphetamine - the active ingredient in ecstasy) occasionally. More infrequently, he did cocaine and “mushrooms” (psilocybin). He described drug use as “a time and place thing,” noting that he did not openly discuss the full extent of his use with his wife or family.

Jenna smoked marijuana daily. She quit for a period of time when she was pregnant and based on this experience of not smoking came to see that marijuana helped her to “be in this world”; to be “calm” and not “judge” others as much. Haylei smoked marijuana and cigarettes daily and drank occasionally. She had tried a multitude of licit and illicit drugs, stating that she liked experimenting and “playing with my brain.” Joshua expressed dissatisfaction at having to hide his use of marijuana stating, “that’s why I have to feel like I’m Osama, bin Laden with my like, uhm: my weed habit.” Paul described Ritalin as “legalized speed,” which he would use to stay awake for days on end. Given the illegal nature of the work he was involved with, he explained, prescribed Ritalin decreased the risk of being arrested on a minor charge of possession.

Analysis

The analysis incorporated attention to discursive features to facilitate an understanding of how narratives are constructed. This included an analysis of how ideas are introduced, how discourses are differentiated, and the interaction between multiple discourses. While several linguistic features may inform discourse analysis, decontextualization and recontextualization are the focus of this article [23].

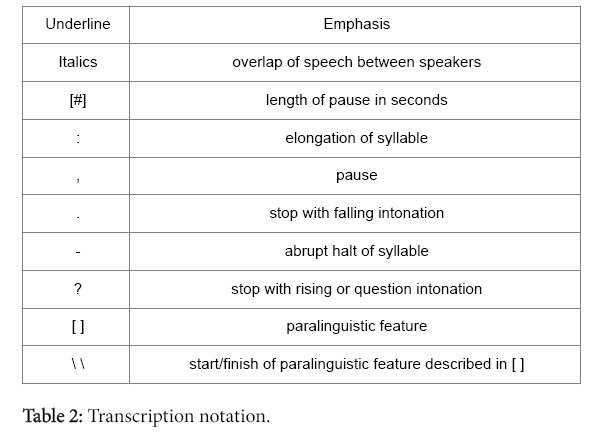

Recontextualization is a process through which meanings are transformed when language is selectively appropriated from one field to another. Transformation of meaning can occur when meanings are taken out of their contexts (de-contextualization) and meaning is put into a new context (recontextualization). Through this process, it is suggested that not only is meaning transformed, but the object loses its previous identity and becomes something new [24]. This process of appropriation can be associated with struggles between social groups in constructing identity and ways of being [23]. In this way, it is possible to identify instances when research participants conform to or oppose dominant discourses (Table 2).

The term recontextualization is a technical term used in academic contexts. However, the concept exists in urban culture contexts as well and is referred to as “flipping the script.” According to the Urban Dictionary [25], flipping the script is defined as:

• “To do the unexpected. To deviate from the norm.”

• “Commonly used in rap battles, it means to take what somebody said against you and to use it against them.”

• “[T]o gain control in a dialogue that is being dominated by another person so that you are now in charge.”

Carr draws on the concept of script flipping in her work, noting, “people can act politically by strategically reproducing - rather than simply resisting - ideologies of language” (p. 19). This process involves drawing on a critical awareness of power relations and entails the “trumping of a rhetorical component” [9]. Flipping the script is a discursive practice that strategically appropriates words and concepts, attending to the implications for associated ways of being, acting, and thinking.

Findings

One of the key findings was that the research participants drew on several discursive strategies to challenge discourses that positioned illicit drug use as wrong or bad. In some instances the research participant overtly refuted negative social “perspectives” about drugs and drug use. They cited peer-reviewed articles, research reports, and documentaries that challenged commonly held beliefs. Frequently, the participants drew on parallel concepts to evaluate the relative individual and social harms; for example, the impact of the “addiction to oil.”

However, overtly opposing dominant discourses about drug use and addiction poses a potential for the statements to be interpreted as evidence of ego defence mechanisms, such as denial. Justification is one such concept that is alluded to by Joshua. In the following excerpt, Joshua explains that his views about marijuana differ from the “current views” that it is “bad.” He notes that it is important for him to be able to “justify” his use of marijuana to others; at the same time he observed that justifying drug use is often considered, in itself, an indication that the drug use is a “bad thing.”

Joshua: But uhm, I think it’s important to realize that, part of my, mpart of the reason I don’t think it’s that bad is ‘cause I, don’t, align myself, with the: the views, the current views other there, that, it’s bad.

Researcher: Right. [1] Yeah so it’s important for you to be able to explain that and,

Joshua: Yeah. And justify that, I guess.

Researcher: [chuckling] And justify it.

Joshua: I even ha:te having to justify it. Like and I shouldn’t have to, ‘n don’t want to. I mean justifying it, ah alone is, is kinda it shows: that it’s, a bad thing. It doesn’t, it’s not true, but that’s just- that’s reality. That’s- perception i-is reality. Right?

His statement that “it’s not true, but that’s just- that’s reality. That’sperception is reality,” is aligned with the epigraph by Faulkner at the beginning of the paper, indicating that deviance is determined according to the dominant discourse perpetuated through a society. What Joshua conveys here is the challenge of talking about one’s drug use, when the nature of talking about drug use in a manner that does not conform to the prevailing dominant discourse is interpreted as evidence that the drug use is bad. Accordingly, personal accounts that do not conform to the dominant assumptions of the listener would be considered invalid and erroneous. This position is further reified by drawing on the concept of defence mechanisms, which present personal interpretations be based on incomplete knowledge, as some aspects are unconscious to the narrator.

Even using the term drug in relation to marijuana was viewed by the participants as conceptually problematic as it was seen to undermine the more benign nature of the substance, particularly in relation to “hard drugs.” In his interview Joshua stated, “I hate talking about it like this because it makes it seem like a drug.” Joshua elaborated on the lexical constraints of representing the experience of drug use.

Joshua: You get- you get pseudonyms: you get ah, you get a name for things, like you “get high,” or:, you know, even, slang terminology stuff. I hate using it, just because, it, I- it’s associated with, slang terms associated with like illicit substances ‘n, illegal activity thing. So I hate using it. But you kind a have to, defend it.

In this way, Joshua highlights the idea that the words used to describe the experiences of drug use are associated with judgments and connotations that reframe a potential positive or neutral phenomenon as negative.

Linguistic hedging, hesitation, and elaboration in relation to the word “need” were apparent. Jenna’s unhesitating use of the word “need” was an exception. She described an incident when she was pregnant, abstaining from marijuana, and facing a frustrating situation, stating, “I’m just like, l: ivid, and I’m like, ‘I need a fucking joint.’”

In many instances when a participant uses the word “need” to describe his or her desire to use a drug (generally marijuana) in a particular situation it was followed by an explanation. Furthermore, the word “need” was one that both Joshua and Sean related to discussions with their partner (girlfriend/wife). Sean describes the type of conversation he would have with his wife when he wanted to smoke up before a movie, “And ah, and then she would say like [higher pitched voice] \“well if you need to.” I’m like ‘well I don’t,\need to like, I’m just being honest. Like I’d, that I would like to.’ [laughs].”

The word “need” may be viewed as reflecting the medical and therapeutic discourses that define addiction according to a physiological and psychological dependence that results in a compulsive need for a substance. As a result, in social conversation where the term “need” might be interpreted as following on a spectrum from a general desire that may remain unfulfilled or an essential necessity, it is interpreted as a physiological and/or psychological necessity. For example, in general, the phrase “I need a new pair of shoes” can be interpreted differently based on the context. It might be said when going to the mall, but it may not be in the person’s budget and so the person does not purchase shoes. It could be said by someone when planning for an event and a particular pair of shoes is required for that event to happen. Therefore, they buy the shoes. Another option might be that someone sees a pair of shoes and laughs that they need a pair of shoes, which they may never have occasion to wear but they buy the shoes anyway. However, in the context of drug use, the potential meaning of the word “need” is narrowed to a perceived necessity. The person who uses the word “need” may use the word to intend the broader meaning, but hesitates or clarifies the meaning based on an awareness that the word might be used by someone else to evaluate their drug use as a problem.

Joshua spoke about the potential for an outsider to reinterpret the meanings conveyed through his use of language in the interviews:

Joshua: and I think\ if a psychologist analysed this [glancing at recorder], this talk,

Researcher: [chuckles]

Joshua: he’d be like.

Researcher: What do you think he’d say?

Joshua: Tear it apart.

Researcher: Oh yeah?

Joshua: Yeah.

Researcher: [laughs]

Joshua: Yeah. Tear it apart.

Researcher: What would you ah: what would you foresee.

Joshua: Well, I- just the- [1] ah th- l- the- I hate talking about it because you make the connection between how someone would sound if they’re talking about, anoth- a really hard drug.

In this discussion, a few important ideas come to light. Joshua uses the metaphor “tear it apart” when he hypothesizes how a psychologist would respond to the interview. In a way, this reflects an analytical approach that dissects aspects of the content rather than developing an understanding of the person’s experience or use of language within context. He emphasizes the incongruence between his intended meaning of words to describe his perspectives and experiences with marijuana compared with the interpreted meanings. Joshua also hesitates when he starts to categorize marijuana as a drug, stating, “If they’re talking about, anoth- a really hard drug.” In this instance, the correction seems to indicate an attempt to construct marijuana as falling outside the concept of “drug,” or “hard drug.”

Joshua explicitly discusses the inherent difficulty of using the Englishlanguage lexicon to describe his use of marijuana and his experiences in a way that contributed to establishing shared meanings and mutual understanding. Instead, the words can reify pre-existing assumptions and interpretations of the listener. Like Joshua, each of the research participants discuss their perspective of drug use in relation to what they consider to be the dominant social perspective. In many instances, the positioning is implicit. It will be demonstrated that, in the context of the interviews, the research participants adopt recontextualization as a way to create new associations with drug-related words in an attempt to constitute and reconstitute the concepts of drugs and pushing drugs.

Flipping the script on “drugs” and “pushing”

It became evident that the research participants evaluated the potential impact of drug use on their health (emotional, physical, cognitive, social) and the health of others. The health impacts were considered according to the type of drug and pattern of use; however, health was also considered from a broader social perspective as well. For example, individual and social effects of drug use were contrasted with the potential global harms of genetically modified foods, the consequences of sexual molestation perpetrated by priests, and the emotional distress experienced by a person who is judged negatively and stigmatized.

In the following example, Sean flips the script on drugs and health, stating:

Sean: Then yeah. Movie on weed. Yeah. They- they certainly go enough- well together. It helps me justify that that gigantic thing popcorn that I’m gonna ingest

Researcher: [laughs]

Sean: Into my body ‘n [laughing voice] \b-before the movie even starts, so.\

The discursive structure positions marijuana as more healthy than popcorn. He draws on the term “justify,” a psychology term indicative of the presence of an ego defence mechanism, and attributes it to the popcorn. In this way, he decontextualizes “justification” from a psychological pathology context and applies it in relation to a socially acceptable activity. Marijuana is recontextualized to a socially acceptable form of consumption that is enjoyable and highly interconnected with the experience of watching a movie.

The research participants draw on various systems of classification and the associated language. For example, marijuana was sometimes referred to as a “plant,” or an “herb.” In the following excerpt, Haylei classifies it as a taxable product.

Haylei: What I don’t understand is, like right now, we get drugs, and it’s like where’d they come from? Like you go up the train there’s, someone’s giving it to some big wig that’s making a who:le lotta money. So why not have that person sell it to the government, who certifies it. As like you know, good to get you high or whatever.

But then, it’s another taxable product. Like liquor and tobacco. That’s gonna, fund health care. N fund, social programs.

Haylei reifies the dominant discourses of capitalist economic principles to re-contextualize drugs as a taxable product that can benefit current political agendas.

While Joshua explicitly expresses discomfort with marijuana being portrayed as a drug in social contexts, he selectively attributes the term in relation to the pharmaceutical context. In fact, in this instance he advocates for marijuana to be classified as a drug, superseding the classification of “natural plant.”

Joshua: Uhm. [2] I know one of the biggest reasons that marijuana’s: ‘legal, is just again, uh: it’s a natural, product that- natural plant. Uh, a:nd, prescription or: pharmaceutical companies don’t want that to be, a drug. I guess it’s more- it is more effective than, a lot of drugs out there. Less side effects, marketed for: for many, conditions. And they tried to replicate, like marinal: replicate marinal, they replicated, it’s like a pill form of weed. ‘er of THC. They’re tryin’a get the people- but it’s not as effective. They tried to make a synthetic, compound.

In this instance, Joshua draws on scientific discourses to highlight natural marijuana as a superior form of medication. It is noteworthy that he uses the word drug in this context instead of medication. Despite refuting the term drug in social discourses he reinforces it in the pharmacological discourses, which can function to alter the meaning. The recontextualization process in both this and the previous example align marijuana as similar to other socially sanctioned activities.

Paul provides a definition for the term designer drugs that is distinct from typical representations. Generally, designer drugs are considered to be psychoactive substances that were developed through experimentation and synthetic modification. It conveys an element of human control to determine the pharmacological properties of the substance.

Paul: The new term is designer drugs?

Researcher: Okay yes.

Paul: That’s really what it is. And, in regards to that, it’s, pretty much your mood. It’s like you go out and, you have a certain event you wanna come out to, you for example would probably pick out an outfit and a pair of shoes for it right? You don’t rea- I guess you could do that too if you wanna go clubbing but, it’s more so like, y-you figure out wwhat you wa:nt. And you figure out what, what craving I guess you’re having. And then at that point you fulfill it.

Paul flips the script by redirecting the element of control away from the production and attributing it to consumption. He presents drug use as a deliberate decision that is embedded in the creation of a particular type of experience in a particular context. This portrayal counters dominant discourses of drug use as being avolitional and habitual.

An excerpt from Haylei demonstrates a more integrated way of conceptualizing psychoactive substances. She distinguishes between drugs that are legal and illegal, but otherwise the use of drugs and experiences are indistinct.

Haylei: I mean, you can walk into a pharmacy and you can buy that stuff. And, it’s like you take one pill and you find out what it does and, I mean you do that with so many and you start mixing them and, you find out what works [3]. And what doesn’t. [1] And then you move on to illegal ones.

Implicit in this statement is a challenge to dominant discourses (and theories) that position marijuana as a gateway drug. Indirectly, she suggests that experimentation with drugs first starts with over-thecounter, non-prescribed drugs. In Canada, early experimentation commonly includes caffeine supplements, Dimenhydrinate (trade name Dramamine), and acetaminophen with codeine.

Paul describes his role of providing illicit drugs to people as similar to pharmacists filling prescriptions. He uses the term “vessel” to describe both roles, explaining that it is neither his role nor the role of the pharmacist to determine whether the drug is appropriate for the customer.

Paul: Because, people always ask, “What would you use” And it, it’s like a pharmacist, right? It’s, if you actually, care about using them because, I guarantee, three quarters of the drugs that the pharmacists is selling, they don’t want you to use. It’s the wrong stuff for you. They’re not gonna say anything. Because they’re a vessel. They’re just there to fill up a bottle. And slap a sticker on and charge you a whole crapload of money. So, I feel that I’m doing the same thing. So, it’s, it’s, I’m trying to help people deal with whatever problems. I’m giving them a Band- Aid.

In a way, Paul elevates his role as slightly more active than pharmacists in the role of helping people.

Paul: I am just, I am more of a, vessel. To whatever you want. If you wanna feel, really happy because your life isn’t happy, I can do that. If you wanna sleep because you have, um like sleep insomnia or something [1]. We-we’ve got that stuff. If- if you wanna do both. If you wanna feel happy, while you’re falling asleep because then you don’t have to worry about something. We’ve got that. If you wanna waste a whole weekend where it just goes by and you don’t even realise it? We can do that too. You know. It’s, we provide things that people want. And it’s, it’s like any other store. It’s just, our catalogue is, not that diverse [1].

By drawing parallels between consumer-based pharmacies and illicit distribution of drugs, there is an attempt to normalize the practices. The therapeutic potential of illicit drugs is emphasized as a way to enhance the perception of socially acceptability.

When the research participants spoke about obtaining illicit substances they used value-neutral terms such as a “source” or a “guy.” As stated by Sean, “we know exactly what we’re taking, we know the source, and we know the guy that we’re getting it from.” Sharon similarly describes the process of obtaining cocaine for cooking by using neutral terms like “a guy,” “get it,” and “give me.”

Sharon: … and I’d go get it from a guy here in town. Who is very influential and very quiet. And he’d cut up four grams for me, I’d sell those, I’d bring him back his money, and he’d give me a gram for selling it.”

In the following excerpt, Sean explains his role in occasionally obtaining marijuana for his friends. He hesitates and corrects himself from using the word “dealer” and substitutes it with the word “guy.”

Sean: You know every once in a while I’ll, buy some extra pot and, ha- you know, and [laughs] \I make no money off it. I’m like the worst pot dea- .\ [laughing voice] \\You know pot guy ever. Becau:se, I’ll like, you know just, sell it for the exact same that I, you know, exact same pri:ce, just to like, [higher pitch] \“ok,”\ y- you know, [higher pitch] \just to like help, help my buddies out\ so to speak.\\

The practice of flipping the script is also evident during instances when the participants speak about the person who grows and supplies drugs. For example, Jenna uses the terms “botanist” and “artist” to describe the craft of growing “potent bud.”

Jenna: You know, like when someone’s a- an amazing botanist, you [laughing] \know\, like I knew a guy in Toronto, didn’t smoke pot. Grew it. [clears throat]. And ah, was an incredible botanist. He knew what he needed to do to make really potent bud. And r-, and that’s not what he did for a living. It was part of his living. But on the other side he was an artist. You know what I mean? So he- he created art, for a lot of different things and a lot of different, functionalities of art. But he also, you know, made growing pot an art form.

Jenna highlights that this person did not grow marijuana as a primary role; instead, she frames growing marijuana as falling within the scope of his talent of being an artist. By doing so, she constructs growing marijuana as being unique, admirable, and something to be valued. She similarly challenges the notion of selling drugs as being inherently unacceptable. In the following except she describes a situation where an acquaintance’s son had been caught selling drugs at school.

Jenna: Like, like this teenage boy for instance. He’s an entrepreneur. You know his is, seeing a need within his high school and he filled it.

Researcher: [laughs]

Jenna: [laughs]

Researcher: Fair enough.

Jenna: [laughing voice] \But that’s what we, we commend people for doing that.

Researcher: True.

Jenna: You know what I mean? Like.

Researcher: True.

Jenna: But then, h-his family and everyone around him is shaming him for it.

During the interview, Jenna did not advocate for supporting the boy to sell drugs in the school, but to shift the focus from the act that is socially unacceptable and illegal to his strengths. Instead of punishing him for engaging in this activity, she suggests that his capacity for selfdirect entrepreneurship be fostered through other means.

In both the excerpts above, Jenna flips the script on drug distribution. She does this, in part, by talking about the situation without drawing on dominant legal, medical and societal terms that might otherwise be used in different contexts.

In contrast, Haylei and Paul use the term “drug dealer” in particular contexts to convey circumstances when they believe that providing drugs is socially and morally unacceptable.

Paul: Or else if we’re drivin’ up to one of the houses, ‘n ‘n we see a dealer standing out in a playground.

Researcher: Right.

Paul: We: we have, l:o:ts of fun with them. At the point of where, they’ll be, five or six of us that go up and say, “Hi.”

Researcher: [chuckles]

Paul: “Maybe you should leave.” And, if not, [2] we will make them leave. At- the end of the story, we, like to- ‘cause you can spot them all like a sore thumb.

Paul distinguishes between his position in an “organization” that provide drugs to people who desire a particular experience and “street level” “dealers.” In this particular example, he conveys that he and his colleagues protect the public, and children in particular, from drug dealers. He reinforces the separateness of this group by stating these dealers “stick out like a sore thumb.”

Haylei also uses the term drug dealer to convey an evaluation of morality, rather than participation in the selling of illicit drugs. She states,

Haylei: And, [4] like you know e- even if you’re a drug dealer you ha- you need a moral compa:ss. You don’t, sell kids, drugs to kids. You know, you don’t, you don’t go sell drugs in a grade school [1]. What’s wrong with you.

Throughout the interviews, the act of selling and buying drugs is described in comparatively value-neutral terms, such as “ I get it from a guy,” unless an aspect of the process was viewed as immoral or inappropriate, such as selling to children.

Jenna describes a situation of an acquaintance that became dependent on prescription medication. She refers to a person who sells marijuana as a “guy” and the physician a “pusher.”

Jenna: So yeah I think he’s been been getting off it and what-not. But, starting to clean up his life, but that was just from prescriptions, from the doctor that when the doctor was writing it she goes “I’m gonna give you some Oxycontins” and he was “you know what I don’t want them.” “Oh, well you just might need them.” You know [speaking loudly] \so that’s a pusher.

Researcher: Yeah right.

Jenna: You know. Like what’s the difference between some guy who’s making a living from selling pot to someone who has a diploma on their wall, you know what is the difference? Do you- you have more credibility because you have a diploma and you went to school. Whwhich is just maddening.

Jenna recontextualizes the term pusher from the connotation of a drug dealer to a physician. The term pusher conveys a meaning similar to that of drug dealer as described above. Accordingly, Jenna constructs this instance of medical prescription as immoral and socially unacceptable.

These findings demonstrate one way of understanding how the research participants challenged dominant discourses of illicit drug use and distribution as being socially unacceptable. The recontextualization of language produces new associations with certain words and concepts. For example, illicit drug use is shaped by drawing on discourses of health, capitalist social structures, and morality. In contrast, licit drug use is shaped to be more closely associated with immoral and unhealthy practices. In this way, the research participants blur the lines of categorizing drugs and drug-related practices as healthy or unhealthy, moral or immoral, socially acceptable or socially acceptable.

Conclusion

The social world is constructed discursively; one’s self is presented and enacted within interpersonal contexts. The findings of this research project demonstrate how language is used to challenge to dominant discourses and re-establish control over public language. Unitary meanings and definitions produced by authoritarian groups are contested and the participants draw on the discursive practice of recontextualization to problematize “arbitrary divisions” [26] and categorization.

The authoritative discourses pertaining to drug use hold significant legitimacy in Western society and have become embedded in social discourses. The ego defence mechanism concept is pervasive in North America, and personal accounts of drug use that do not conform to the dominant discourses are attributed to the person engaging in denial, rationalization, justification, intellectualization, or minimization. It is essential to recognize this aspect of the context when analysing the narrative accounts. The research participants are not in a social location that permits overt discussion about drug use and they are accustomed to negative judgments being expressed about drug use. Essentially, the act of denying that one has a problem associated with drug use is considered psychological evidence that one has a problem. Therefore, in Canada, to directly dispute dominant discourses of drug use opens one to being discounted as a reliable authority on the subject.

As a result, in this context, the research participants needed to find spaces to indirectly challenge authoritative discourses and maximize the opportunity to shape and influence internally persuasive discourses. Often, this means drawing on and conforming to other dominant discourses such as health discourse and capitalist discourses. These discourses afford the speaker socially acceptable and authoritative platforms from which challenge the discourses of drug use.

It may be considered that re-contextualisation harnesses the centrifugal forces of meaning production and provides an indirect means to challenge dominant discourses. Flipping the script affords a way for individuals and collectives to talk over authoritative discourses and break free of definitions, explanations, and categorizations [27]. This is a potentially powerful endeavour, undertaken with the intention of reconstructing knowledge.

It can reasonably be expected that the centrifugal or recontextualised meanings are not necessarily known outside certain circles, so the interpretations made by a third party neglect these meanings and apply the dominant, centripetal meaning. Accordingly, this research may have several implications.

The intention of this research was to inform health professional practice to more effectively address drug use with clients. It is important that health professionals evaluate the ways in which they form understanding about their clients and their experiences with drug use. More research is required to examine the validity of medical and psychology practices that reinterpret individual accounts of drug use from the default assumption of psychological pathology. Researchers and health professionals need to recognise that language is embedded within social, political, and historical contexts as is use to do things and create things, not to simply convey an inner truth.

Furthermore, health professionals frequently reify dualistic conceptualization of pharmaceutical medications and drugs. These distinctions potentially perpetuate an over-reliance on medical options and inadvertently contribute to social practices of drugs as being an ideal means to enhance quality of performance and quality of experience. There is, arguably, little tolerance for physical and emotional discomfort in today’s society. Furthermore, individuals are expected to perform better and faster without critiquing of the social and institutional systems that are placing increasing, often unrealistic, demands on the person.

Author has been asked several times what motivated the research participants to engage in this research project. While each person surely had their own reasons, one common feature was that the research participants advocated for was a more open understanding about drugs in society. It was suggested that many individuals may feel shunned by their family, friends, and society, which can increase their experience of emotional distress. Many people who might have questions about their own drug use may avoid seeking support due to the potential negative consequences associated with self-disclosure. As a result, the potential for problems to develop or escalate. Furthermore, it was recommended that children have access to information about drugs that are not fear-based and do not represent only the potential harms.

The research participants demonstrated a strong awareness that the implications of their involvement in the project extended beyond the context of the interview, and that the information would be shared in academic, research, and health professional contexts. Accordingly, this research project afforded them a public voice, channeled through a system of knowledge that hold significant legitimacy in society–a university-based research project. This is a legitimacy of voice that is frequently not afforded to individuals when they discuss their own drug use. Mehan expounds on the hierarchy of voice in medical contexts, stating, “Some persons, by virtue of their institutional authority, have power to impose their definitions of the situation on others, thereby negating the others’ experience….relegating [the other’s] experience to an inferior status” [28].

A limitation of this type of research project is that it is situated within a particular cultural and historical location and the findings are not considered to represent a universal truth. When drawing on discourse analysis, there are many techniques that can be implemented, but not all feasible. For this project author selected the one (recontextualization) that emerged from the analysis and supported the political intentions of the work, though many other approaches may be used to develop a deeper understanding of the discursive practices. The sample size limits generalizability of findings, but is consistent with discursive methodologies designed to examine large sets of linguistic data attained from select sources.

Participant discourse is partially influenced by the interview context and interviewer-interviewee context. The participants did express some hesitation regarding self-disclosure and may have concealed some information. However, features of heteroglossia were discernable within and across participant accounts, providing valuable data for analysis.

Future studies are required to explore the linguistic features of language in relation to interpretation of ego defense mechanisms, including fluency features (e.g., hedging, modalization, hesitation, assertions, argumentation, face work [29-33]. Studies may be designed to collect prospective data that explicitly integrates discursive methodology, or may involve secondary analysis of data already collected. The grey literature also affords an extensive opportunity for analysis, including movies, television shows, and newspaper articles, where concepts of substance use and denial and reified and shaped.

Larger studies, involving more participants, are required to explore the nature of substance use among a broader population of individuals who use substances and do not consider their use to be problematic. Assumptions regarding the inherent risk for harm need to be suspended to facilitate a nuanced understanding of substance use in society, to understand processes of controlled use and potential for substances to be selectively integrated into daily life with intention and expectations of enhancement.

References

- Faulkner W (1990) As I lay dying, New York, NY: Random House, Inc.

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Toneatto T, Leo GI (1993) What triggers the resolution of alcohol problems without treatment. Alcohol ClinExp Res 17: 217-224.

- Stinson FS (2005) Comorbidity between DSM-IV alcohol specific drug use disorders in the United States: Results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence: 80:105-116.

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Best practices (2001) Concurrent mental health and substance use disorders, Ottawa, ON, Canada: Publications Health Canada.

- Didden R (2009) Substance abuse, coping strategies, adaptive skills and behavioural and emotional problems in clients with mild to borderline intellectual disability admitted to a treatment facility: A pilot study. Research in Developmental Disabilities: 30:927-932.

- Granfield R, Cloud W (2001) Social context and "natural recovery": The role of social capital in the resolution of drug-associated problems. Subst Use Misuse 36: 1543-1570.

- Warhol R (2002) The rhetoric of addiction: From Victorian novels to AA, in High anxieties: Cultural studies in addiction, University of California Press: Los Angelespp:97-108.

- Freud S (1924) The loss of reality in neurosis and psychosis. Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Vol. XIX, London, UK: Vintage.

- Carr ES (2011) Scripting addiction: The politics of therapeutic talk and American sobriety Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Guilfoyle M (2006) Using power to question the dialogical self and its therapeutic application. Counselling Psychology Quarterly 19: 89-104.

- Reinarman C (2005) Addiction as accomplishment: The discursive construction of disease. Addiction Research and Theory 13: 307-320.

- Gubrium JF,Holstein JA (2003) From the individual interview to the interview society, in Postmodern interviewing, GubriumJFand Holstein JA, Editors, SAGE Publications: Thousand Oakspp: 21-50.

- Miller L (2008) Foucauldian constructionism - Handbook of constructionist research. The Guilford Press: New York, NYpp:251-274.

- FoucaultM (1990) The history of sexuality Volume I: An introduction, New York, NY: Random House, Inc.

- Bakhtin MM (2008) The dialogic imagination, ed. M. Holquist, Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- Barker C, DGalasinski (2001) Cultural studies and discourse analysis: A dialogue on language and identity. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc.

- van DijkTA (2008) Discourse and power, New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Strauss C (2005)Analyzing discourse for cultural complexity, in Finding culture in talk: A collection of methods. Palgrave MacMillan: New York, NY.

- Tanggaard L (2009) The research interview as a dialogical context for the production of social life and personal narratives. Qualitative Inquiry 15: 1498-1515.

- Riessman CK (1993)Narrative analysis. Qualitative research methods. Series 30, Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Chase SE (2005) Narrative inquiry: Multiple lenses, approaches, voices, in The Sage handbook of qualitative research. In: Denzin NK Lincoln YS (eds.) Sage Publications Inc: Thousand Oaks, CA: 651-679.

- Hill J (2005) Finding culture in narrative, in Finding culture in talk: A collection of methods, Quinn N, Editor, Palgrave MacMillan: New York, NYLpp: 157-202.

- Fairclough N (2010) Critical discourse analysis: The critical study of language, Harlow, UK: Pearson Education Limited.

- Meyer M (2001) Between theory, method, and politics: Positioning the approaches to CDA, in Methods of critical discourse analysis, Wodak R and Meyer M, Editors, SAGE Publications Inc: Thousand Oaks, CApp: 14-31.

- Urban dictionary (2012) Flip the script.

- Bourdieu P (1991) Language and symbolic power. Thompson, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- MansbachA (2001)Genius b-boy cynics getting weeded in the garden of delights, New Orleans, LA: Subway & Elevated Books.

- Mehan H (2010) Oracular reasoning in a psychiatric exam: The resolution of conflict in language, in The discourse reader, Jaworski A and Coupland N, Editors, Routledge: New York, NY: 523-545.

- Clark HH, Fox Tree JE (2002) Using uh and um in spontaneous speaking. Cognition 84: 73-111.

- Smith VL, Clark HH (1993) On the course of answering questions. Journal of Memory and Language 32: 25-38.

- Martin J (2005) The language of evaluation: Appraisal in English, Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fairclough N, Fairclough I (2012) Political discourse analysis, New York, NY: Routledge.

- GoffmanE (2005) Interaction ritual: Essays in face-to-face behaviour, New Brunswick, NJ: Aldine Transaction.

Relevant Topics

- Addiction Recovery

- Alcohol Addiction Treatment

- Alcohol Rehabilitation

- Amphetamine Addiction

- Amphetamine-Related Disorders

- Cocaine Addiction

- Cocaine-Related Disorders

- Computer Addiction Research

- Drug Addiction Treatment

- Drug Rehabilitation

- Facts About Alcoholism

- Food Addiction Research

- Heroin Addiction Treatment

- Holistic Addiction Treatment

- Hospital-Addiction Syndrome

- Morphine Addiction

- Munchausen Syndrome

- Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome

- Nutritional Suitability

- Opioid-Related Disorders

- Substance-Related Disorders

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 10524

- [From(publication date):

April-2016 - Jul 17, 2024] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 9844

- PDF downloads : 680