Exploring Factors Affecting Trust in Construction Virtual Project Teams

Received: 19-Nov-2021 / Accepted Date: 03-Dec-2021 / Published Date: 10-Dec-2021

Abstract

Many organizations have embraced a new reality of virtual working, which poses new challenges for leaders. Virtual teaming has numerous advantages, but it also increases the danger of misalignment and lack of cooperation, which may have a negative impact on team trust and employee engagement if not done correctly. Team leaders and organizations must understand the strategies for establishing and maintaining trust in Virtual Project Teams (VPTs) to maintain team members performance after transitioning to decentralized workplaces. This study examines the process of building trust in VPTs by analyzing the factors that influence trust in virtual teams. Qualitative interviews with ten experienced professionals in the Middle East’s construction sectors were conducted to gain insights for the study. The study results revealed that factors influencing trust among VPTs in the Middle East construction sector show some unique attributes. The effects of prominent factors, including organizational culture, communication, diversity, leadership, and task-technology fit, and team member characteristics on trust-building in VPTs were identified. Understanding the interdependence between these factors and trust will help virtual team members remain focused on achieving effectiveness and efficiency in their work.

Keywords: Virtual project teams; Trust; Organizational culture; Construction sector; Market change

Introduction

The use of technology to organize interactions and duties in virtual space is significant in today’s workplace [1]. Given the advancement in technology, Virtual Project Teams (VPTs) have become commonplace in providing opportunities for collaboration across time, space, and organizational boundaries, being an essential component of the organizational fabric, helping firms adapt to fast market change [2,3]. For example, the global adoption of VPTs grew from 60 percent in 2003 to 85 percent in 2016 [4,5]. In addition, according to a poll of 3000 managers from 100 countries, 40% of their employees spend at least half of their time on work utilizing VPTs [6]. VPTs are geographically distributed teams and operate interdependently, utilizing technology to communicate and interact across time and space [7]. Due to the nature of VPTs, trust have been reported to be critical factor that affects team performance [3,8-10]. Because asynchronous communication prevents social information exchange, trust develops more slowly in virtual teams than in face-to-face teams [11]. Remarkably, an on-site team’s interactions are mostly face-toface [3]. However, such differences are becoming blurred in the modern workplace, as on-site team members increasingly rely on technology for communication, coordination, and other activities required for team project completion [12,13]. As a result, virtual relationships are increasingly intertwined with face-to-face interactions [14]. According to a recent survey, 70% of business professionals expect virtual work to grow in the future [15].

Despite its widespread use and prominence, there is evidence that doing work through virtual interactions has downsides, particularly in terms of encouraging collaborative behaviour among team members [16]. The nature of interactions on technological platforms has frequently been attributed to reduced collaboration. Members of virtual teams, in particular, have a poorer feeling of cohesion and personal connection amongst members, owing to little or no face-toface interaction [17]. While previous research has investigated specific elements influencing the success of VPTs, such as team diversity, the degree of communication, organizational culture, conflict among teams, and team members’ characteristics, trust has been identified as a critical element that affects VPTs [3,18-22]. It was revealed in a recent study that virtual distance could lower your team member’s trust by 83% [15]. However, a holistic understanding of the relationship between trust and factors affecting the effectiveness of VPTs is still lacking [22]. If trust is critical to VPT success, there is a need to understand what fosters or discourages trust in VPTs [12]. In doing so, it is critical to recognise that variables influencing trust in VPT will include evaluations of team members and assessments of the process that facilitates virtual interactions [3].

Since trust enhances interaction, coordination, and performance, and is an important success element for VPTs in general, VPT leaders must constantly work to build, strengthen, and sustain trust among team members as well as between themselves and their team members [5,23-25]. However, even though trust has become one of the most studied variables in the VPTs literature, coupled with the growing constrained by a startling lack of clarity about how various factors impact trust in VPTs [15,26]. Taken together, research indicates that VPTs will be a fixture in the future workplace and that trust may serve as an essential mechanism for addressing problems connected with technology use, communications, and team diversity [5]. Hence, a greater knowledge of how to enable VPT functioning via trust will be important for construction professionals and project managers to direct the future workforce more efficiently and effectively. Against this backdrop, this study explores factors affecting trust-building in VPTs in the construction sector, through a comprehensive qualitative analysis. The rest of this paper is organized as follows. First, we discuss the relevant literature including the result of scientometric analysis used to support the argument in this study. We then describe the methods used for data collection and analysis, followed by the results and discussions of findings and the conclusion.

Building trust is the bedrock in the formation of a successful virtual team [27]. This section describes the concept of trust and establishes the position of trust in VPTs.

Concepts of trust and VPTs

Trust is defined as the honesty, fairness, and quality of relationships among workers inside an organisation, with the primary goal of ensuring excellent employee interactions, particularly in confusing and unclear circumstances [28,29]. The notion of trust is conceptualised differently in different professions [5]. Trust is a multi-dimensional concept that originates from different routes. Trust is developed at many levels, from societal to industrial, organisational, project and inter-personal [22]. Investigated the development of interpersonal trust between key team members [30]. Still, contextual data and other studies showed a variety of contexts that impacted the levels of trust in the inter-personal context. In the light of the literature review on trust, it is proposed that trust be categorised into system-based, cognitionbased and affect-based [31]. System-based trust is concerned with formalised and procedural arrangements, with little regard for personal concerns. These arrangements foster confidence and enhance the communication channel among members of society [32]. Cognitionbased trust emerges from confidence based on information that indicates an individual’s or organisation’s cognitive bearings. Such information can be exchanged through engagement or conversation, both formal and informal. Affect-based trust is built on a sentimental foundation. It refers to an emotional link that binds individuals to invest in personal attachment and be considerate of one another [32]. The formation and maintenance of trust in virtual teams are often temporary and depends more on the cognitive element than the affective element [33]. Building trust is also challenging in the construction industry context as teams may not work together for a reasonable time long enough to form and maintain trust.

Generally, a team is defined as a group of “individuals interacting adaptively, interdependently, and dynamically towards a common and valued goal” [34]. As a particular type of team, VPTs are frequently defined as “groups of geographically and/organizationally dispersed co-workers that are assembled using a combination of telecommunications and information technologies to accomplish an organisational task” [35]. The following are some of the concepts associated with virtual teaming as established from the literature. Virtual teams overcome the limitation of space, time and organisational boundaries that traditional teams face. This helps to reduce the relocation and travel costs [22]. Virtual teams assist in the reduction of time for the completion of activities of the projects. Therefore, it reduces time-to-market as it becomes quicker in executing tasks [36, 37]. The concept of virtual teams connects the experts in highly specialised fields digitally. This also helps organisations access the most qualified individuals for a particular job regardless of their location [24]. Virtual teams produce better outcomes and attract better employees. It generates the greatest competitive advantage from limited resources [22].

VPTs are very useful for projects that require cross-functional or cross-professional boundary input [38]. Virtual team members perform their work without concern of space or time constraints [39]. The team members can be assigned to multiple, concurrent teams, often helping many virtual teams with their expertise. The team communications and work reports are available online to facilitate swift responses to the demands of a global market. Employees can also easily accommodate both personal and professional lives [40]. Virtual teams are significantly different from traditional teams. In the traditional team, the members work next to one another, while in virtual teams, they work in different locations. In traditional teams, the coordination of tasks is straightforward and performed by the members of the team together; in virtual teams, tasks are much more highly structured. Also, virtual teams rely on electronic communication, whereas traditional teams do not [5, 41]. Initially, the concept of virtual project teams was not welcomed by many managers because it requires different ways of supervision for handling virtual team’s effectiveness [35]. Although there are numerous types of trust, cognitive-based trust is likely the one that best defines trust amongst virtual team members [22,42]. This form represents one’s decision to trust based on technical competency and fiduciary duty to perform, as well as other “good reasons” [43].

VPTs are a new type of organisation that has the potential to transform the workplace by providing unprecedented levels of flexibility and responsiveness. However, VPTs cannot be deployed blindly and do not constitute an organisational panacea [44]. Extensive study is required to comprehend the design features of effective virtual teams. Interpersonal trust becomes crucial in this dispersed working style since contracts, regulations, and processes may be difficult to implement. According to Handy (2000), reaping the virtual organisation’s benefits requires rediscovering how to govern organisations based on trust rather than control. To function, virtuality needs trust: technology on its own is insufficient. The efficiency of VPTs is dependent on qualities such as speed and flexibility, which necessitate high levels of mutual trust and collaboration [45]. Modern engineering design, project management, and manufacturing are frequently carried out by internationally dispersed teams of highly professional engineers collaborating across global boundaries to develop complex designs [46]. There is not enough time in these temporary groups for traditional ideas of trust to work. Trust development in virtual teams is particularly challenging since it is impossible to judge teammates’ trustworthiness without meeting them [47]. Furthermore, because the lifespan of many virtual teams is very short, trust must be developed rapidly [35]. Nonetheless, trust-building is critical for the effective completion of virtual team tasks [48].

Despite extensive study on project success determinants, many projects still fail, as demonstrated by many studies [8]. The failure is attributed to deficiency in project collaboration and lack of trust [49,50]. According to the literature on virtual teams, trust is a key component for teams with different geographical locations, cultures, and spaces. Trust-building is a difficult and repetitive activity for any team, but it becomes considerably more difficult in a virtual setting, where members have fewer opportunities for human connection. Opined that project team trust and collaboration have a complex and intertwined relationship with project success that should be investigated further since both of these unique case studies have intrinsic limitations to generalizability [50,51]. Previous research indicates that stakeholders’ perceptions of project success are critical, particularly in international development [52]. However, there remains a gap in the literature with respect to understanding the links between the constituents of VPT functionalities and trust from the perspectives of construction professionals, which will be explored in this study. To understand how trust is affected in VPTs, we explored some established factors in the literature. We constructed a theoretical framework that guided the research using prior research findings, as shown in Table 1. The framework focuses on the interaction between trust and factors that are based on the perspective of work practices, which explains the interdependence of leadership, people and technology as its fundamental assumption. This view provides a theoretical lens to study factors that affect trust in VPTs.

| S/No. | Key themes | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Effect of Organizational Culture on Trust | Choi and Cho (2019); Katane and Dube (2017); Dietz et al. (2010) |

| 2. | Effect of Communication on Trust | Henderson et al. (2016); Malhotra and Majchrzak (2014); Shachaf (2008) |

| 3. | Effect of Diversity on Trust | Gibson and Gibbs (2006); Han and Beyerlein (2016); Shachaf (2008) |

| 4. | Effect of Team Member Characteristics on Trust | Schulze & Krumm (2017); Arman-Incioglu (2016) |

| 5. | Effect of Leadership on Trust | Charlier et al. (2016); Deloitte Denmark. (2021); Efimov et al. (2020); Hoch & Dulebohn (2017) |

| 6. | Effect of Task- Technology Fit on Trust | Munkvold & Zigurs (2007); Shachaf (2008); Owens & Khazanchi (2018) |

Table 1: Key themes of the research.

Materials and Methods

The study was empirical, deductive, and qualitative in nature. Deductive in the sense that the study was driven by an expanded model of trust and VPTs in our previous study. A similar approach was used in a relevant study on global virtual teams [53]. Qualitative method was used to collect data to get insight into respondents’ personal experiences and elicit subjective comments [54]. A set of six themes (Table 1) were extracted from our previous study and were designed to form interview questions. The primary philosophical consideration of this research was linked to the essential requirement of understanding the effects of various factors of VPTs on trust.

Sampling approach

Since establishing broad generalisations was not the primary goal of this study, a non-probability sample design combining purposive and convenience sampling was adopted [53,55]. This approach facilitated the selection of an information-rich sample of ten participants, drawn from The Emirates Oil and Gas directory, Middle East Building and Construction Directory and The Blue Book Building.

While there may be concerns regarding sample size, interview lengths, and the validity of the findings, it is well known that qualitative research does not always require large samples since data saturation can occur with fairly small samples. Also, a past study on trust and virtual teams interviewed ten participants [56,57]. All participants had roles as either project managers or team members and were selected; based on their participation in virtual project teams in the Middle East for over five years.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were utilised to gather information relevant to the research questions while allowing respondents to make spontaneous comments [53]. Semi-structured interviews are a great way to garner important information from experts [58]. This method was used because, compared to other data collecting approaches, semi-structured interviews allowed for more in-depth research of the participants’ perspectives on the major challenges impacting virtual project teams in this study [55]. Interview questions were asked to elicit the participants’ knowledge of virtual teams and establish issues of trust they encounter when delivering virtual teams projects. These questions were supplemented with others as needed, allowing the researchers to investigate with greater accuracy and detail.

Prior to the interview, research information sheet with interview questions was sent to the potential interviewees. After their agreement to participate in the study, the date and place of the interview were agreed upon according to the interviewee’s preferences. All ten interviews were conducted face-to-face, and each lasted for approximately 90 minutes at the interviewee’s place of work. On the interview date, each interviewee was given a reminder about the research purpose. Then the consent form was introduced to the interviewee, explaining the confidentiality of the data and the assurance of anonymity of the participant’s identity. The participants were asked to sign the consent form. The interviews were audiorecorded, at the interviewee’s consent, then transcribed and later coded [59]. The interview began with the introduction of the interviewee with general questions such as job role and responsibilities, years of experience, nature of work and company size. This information helped to break the ice between the interviewee and interviewer. A detailed description of the interviewees’ profiles is presented in Table 2. Out of the ten professionals interviewed, six were team members, and four were team leaders of VPTs of the construction sector in the Middle East. There were two female and eight male participants. The interviewees had a varied range of experience in the Middle East, Holland, UK, India, Japan, and Korea, but they have all participated in the delivery of construction projects using VPTs in the Middle East. The participants worked in various fields, including Projects, Construction and Engineering, Bids and Proposals, Project Estimations, Engineering Procurement and Construction (EPC), and Consultancy.

| S.no. | ID | Type of experience | Job title | Years of experience |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | AS | Bids and proposals, project estimation | Project Manager | 22 years |

| 2. | VI | Construction, Consultancy | Team member | 13 years |

| 3. | PR | Construction engineering | Project Manager | 11 years |

| 4. | SH | Construction , EPC | Team member | 15 years |

| 5. | RL | Projects-construction and engineering, automobile industry, manufacturing Industry | Team member | 12 years |

| 6. | RA | Consultancy, contracting, geotechnical projects | Team member | 12 years |

| 7. | KA | Project engineering | Project manager | 17 years |

| 8. | RO | Project planning- infrastructure projects | Team member | 10 years |

| 9. | KO | Project management | Team member | 12 years |

| 10. | NA | EPC | Project manager | 20 years |

Table 2: Information about participants meetings.

Method of analysis

The recorded interviews were manually transcribed and analyzed using the following steps: arranging the data; categorizing the data based on similarities and contrasts in the replies of the participants. Content analysis was adopted because of the relatively small number of interviews conducted. This approach helped organize the textual interviews since the interviewees referred to the same themes in various questions. For example, interviewees did not explicitly address some themes, but the researcher was able to capture these themes in the discussion during the interviews.

Findings and discussion of interview

This section explores the contents of the findings from the interviews and analyses them qualitatively. The following subsections describe and report the main themes as perceived by the participants.

Challenges involved in building trust in virtual project teams

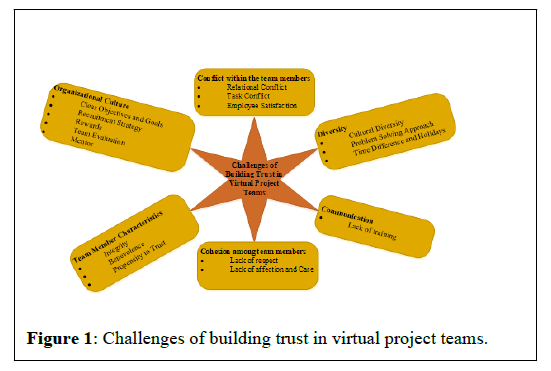

Because of participants’ vast and varied experiences, they were first asked about the major challenges they encountered in building trust in virtual project teams in the construction sector of the Middle East. The participants provided detailed information about their challenges during their tenure as either team leaders or team members for their projects. The challenges are summarized and divided into six categories from participants’ points of view, as shown in Figure 1.

Results

According to AS, “The lack of communication and the time difference between different countries are the major challenges for building of trust among team members”. RA confirmed that, “As the teams are at different geographical locations, it is difficult to build respect, affection and care and this leads to lack of cohesiveness. And this leads to distrust among team members.” NA added that “Lack of clear objectives and goals in an organisation leads to distrust among team members as they are not sure of what they are supposed to do.” KO pointed out that “The unresolved conflicts and employee dissatisfaction leads to problems among the virtual project teams. Also, lack of proper reward policy in an organisation leads to dissatisfaction among employees leading to distrust among employees”. SH revealed that “A fair policy of team evaluation always leads to encouragement among the team members. The biasing policy of team evaluation always leads to distrust among team members and hence they stop sharing the information which leads to delay in the execution of the projects.” PR confirmed that “Trainings on conflict management and personality development greatly helps in building communication skills which enhances the relationship bonding among the team members. Also, the team-building exercises greatly help in understanding the teammates and helps to reduce the friction among the team members.”

Both RA and KO thought that “The cultural diversity brings in some issues which sometimes leads to confusion and distrust among the team members”. RL highlighted the importance of team member characteristics in building the trust, “It is very important to have positive traits in team members’ personality which greatly helps in building the trust. Lack of integrity, benevolence and not having a propensity to trust attribute, lead to distrust among team members.”

The findings align with previous studies [27,60-62]. Therefore, relevant stakeholders and senior management of the construction companies need to acknowledge and highlight these challenges to find radical solutions in developing trust among team members. Project managers of construction firms need to understand these issues to have proper coordination among team members who are geographically dispersed. By understanding these challenges, it should be a win-win situation both for management and virtual project teams.

Effect of organizational culture on trust

The interviewees perceived trust as a core organisational culture. They emphasised that trust is essential for different areas, reflecting how team members are selected, evaluated, rewarded, and mentored to support their objectives. Participants replied that trust should be incorporated as a significant organisational core value to retain a competitive edge since trust is the foundation of all business transactions. Organisational culture includes norms regarding the free flow of information, shared leadership, and cross-boundary collaboration [42]. The organisational culture consists of clear objectives and goals for the team members, its recruitment strategy, reward structure, team evaluation, availability of mentors in the organisation, and degree of task interdependence [22,60].

The success in creating a virtual world will depend on how clearly the objectives and processes are defined to accomplish the objectives have been designed [22,63]. NA in his interview believed that “Team members who do not know what they have to deliver and when they need to, are at higher level of personal risk which is central to trust building and this has to be made clear by the organisation where they work.”. PR stated that “When the team members are committed to the team objectives, it brings in the success of entire team as they are very clear about their long-term goals.” Further, RL stated that “If the goals and objectives in an organisation are made clear and agreed upon, this greatly reduces the uncertainty regarding performance expectations. These goals also challenge team members giving them a heightened sense of urgency relative to accomplishing team-based objectives.” The interviewee KO agreed by stating that “A transparent organisational culture which sets clear objectives for its teams and employees enhances trust among its staff and hence the teams.” Also, RA insisted that “Employees of an organisation which has set clear objectives for them are happier than the organisation which has not done so far. But if the organisation does not give clear objectives, it’s always like a random thing because they do not know for what objective they are working”. Therefore, these goals and objectives help build collective team identity, fostering the cooperative behaviours necessary for team trust-building.

Team selection is another factor that differentiates successful teams from unsuccessful ones. Recent research, for example, underlines the tools and strategies that may be utilised in virtual teams to create trust, such as creating a good organisational climate and culture, selecting a unique approach to the recruiting and selection process, and employing an effective team leader [24]. RA believed that “The selection criteria which an organisation uses greatly affect the type of people that will be in teams. The organisation needs to recruit people that are most suited for a particular project”. If that does not happen, there is a high risk of distrust among the team members as they do not trust teammates’ capabilities. KA stated that “Improper hiring policies of the organisation bring in lot of discomfort and distrust within the team.” PR insisted on having “Good recruitment cell which has a strong HR who chooses the right kind of candidate for the right type of project. It greatly helps to bring in the positive changes in the team, hence building trust within the team.”

Revealed that rewarding team members based on individual decision outcomes or team decision outcomes would increase the trust of team members in the organization [9,60]. The interviewee AS added by saying that “When members’ contributions to the group cannot be identified readily, they respond by identifying less with and contributing less to the group.” KO indicated that “A clear incentive structure helps in improving attitude in virtual team members.” RL raised an important point that “The incentives with a supervisory component are the most effective way to improve the attitudes of virtual team members.”

Team evaluation refers to a mechanism of fairness of outcomes, fairness of decision-making procedures, fairness of interpersonal treatment and adequacy of information about decision-making procedures and outcome distribution [10,64]. Opined that cognitive trust is founded on the judgment of another party’s dependability, competency, and capabilities, or, in other words, on the evaluation of ability and integrity. Boon and Holmes (1991) suggested that affectbased trust development is restricted to romantic relationships. However, it is thought that developing affect-based trust at work increases the process of evaluation and information exchange, as well as team performance and well-being [65]. Therefore, both cognitive and affect-based trust apply as reflected in the responses gathered from the interviewees. According to the interviewee SH “The team members become more confident when there is a fair procedure of team evaluation as it greatly increases the trust among the team members. They start believing that there is no biasing as far as the evaluation is concerned and hence greater productivity is achieved.” RL and KO believed that “A fair evaluation of team which does not include favoritism becomes a motivational tool for trusting the organisation and reflects in the trust for team members too.” AS stressed that “There should not be any subjectivity in the evaluation of team; otherwise it brings in lot of anger within the team.” KA shared his experience by saying that “In my previous organisation, there was bias in evaluating teams’ work and the employees. It created so much restlessness among the team members that they were not ready to trust not only other colleagues but their teammates as well”. RA shared that “In Middle East, the organisational policies go by government rules and if the evaluation does not get executed fairly, the employees can file a case against the organisation. So in that perspective, the team evaluations are kept very fair.”

Mentors in an organisation play a great role in developing trust among the team members. In a virtual work setting, as the employees are working in different locations than their managers, the opportunity for face-to-face contact is limited. This means that the manager has significantly fewer opportunities to view employee behavior than would exist in a conventional work setting. Trust can be used as a coordination and control mechanism as observing behaviours is no longer a feasible solution in a virtual workplace [63]. One important onboarding strategy in a virtual team is designating a mentor to a new employee who will answer any questions and aid to smooth the transfer and learn fast about a new environment [66]. RO believed that “If the team member gets emotional support from somebody in the organisation, the half of the job is done in building trust among the employees.” PR stated that “Even though our manager is at a different location, occasionally when he supports and guides us in our work, it becomes great motivational factor.” VI enforced that “Often the frustrations of virtual team members greatly demotivate the team and affect the team’s productivity. Therefore, the guidance from somebody in the organisation, be it a team member or superior, certainly helps bring the team together.”

Another factor affecting trust is task independence within VPTs [21].Defined task interdependence as the degree to which work requires interaction among employees. All project teams, especially virtual project teams, live on dependency, thus building individual trust within teams is critical [27]. The higher the task interdependence, the more effective the team. The interviewee KO indicated that “The task interdependence greatly motivates the teams to work together as they can see the impact of their contribution in their projects as success”. PR highlighted the importance of it by saying that “Task interdependence also shows the dependence of one’s performance on one’s skills and actions. This gives the team members a great sense of responsibility among the team members and helps in team building”. SH insisted that “As the task interdependence increases in the projects, there has to be more interaction and exchange of information. This increase in interaction has been seen as positively linked to the trust within the virtual project teams. NA confirmed the importance of task interdependence by saying that “The task interdependency facilitates trust development as it involves increased need of adjustment, communication and coordination.”

Therefore, all the interviewees highlighted the importance of organisational culture in building trust in the organisation. They stressed that it needs a strong commitment of senior management with respect to the strategic planning of virtual project teams. Organizations should provide appropriate support systems, including clear objectives and goals, evaluation and compensation systems, mentoring, and degree of task interdependence.

Effect of communication on trust

The development of trust is linked to increased communication among members [35]. Managing virtual project teams necessitates extra effort to achieve project goals through efficient communication and appropriate technologies [27]. The communication aspect of team members consists of degree of communication and requirement of training by the team members of the virtual project teams [42]. suggest that effective communication, especially during the early stages of the team’s development, plays an equally important role in gaining and maintaining trust. The interviewee RL is of the view that communication is the biggest challenge for virtual project teams as they are globally distributed. Therefore, they need to have more communication. Initial kick-off meetings are very much required to build trust among dispersed teams.” RO indicated that communication is the key to build trust, but at the same time, it’s a great challenge for virtual teams. Organisations need to play an important role in establishing effective communication within the teams. This can be accomplished by imparting regular training on problem-solving and communication skills.” When asked to the participants whether language acts as a barrier to the development of communication, all of them were of the view that “In Middle East, the common language is English. So the language is never a barrier in communication as anybody who seeks employment here needs to have this minimum requirement.” PR stated that “The teams who send more social communications achieve better social and emotional relationship resulting in more trust among its team members”. KO and RL added that “The teams are highly satisfied when there is effective coordination and communication.”

Suggested that managers can send employee for training to acquire skills and experiences that will make them good team players [22]. The training could allow employees to experience the satisfaction that teamwork can provide. The training could be in the form of workshop to help employees improve their problem solving, communication, negotiation, conflict management, and coaching skills. In this regards, NA suggested that “In case of new technology to be used by virtual team members, computer training related to more advanced skills may be used to improve virtual teams’ efficacy.” VI gave an example of his own organisation, stating that “Our organisation imparts training on interpersonal skills, conflict management and problem-solving so that when the employees go back to their respective virtual project teams, they should perform and communicate more acceptably with a positive approach. This surely makes team members comfortable with each other and helps in building the trust.” AS was of the view, “In my organisation, they do a special focus on communication. They involve everyone in the training of conflict management, interpersonal skills to communicate and write effectively. With this, the teams can respond to each other more efficiently. Definitely, communication creates a good environment to build trust in virtual team members.” And finally, PR indicated that “Our UAE branch gives high importance to intracompany communication and even imparts various corporate communication and interpersonal skills training. This greatly affects the positive building of trust.”

Understanding the right sorts of technology for virtual team communication and engagement and how to utilise them is a crucial skill for virtual team leaders and team members to develop [67]. Also, establishing communication standards early in virtual teams and communicating with team members via courteous electronic communications help develop interpersonal connections and trust [51,68]. Therefore, the senior management and project managers have to build up strong communication among virtual team members by having greater degree of communication and developing various training programme. This surely results in increased cohesiveness and team satisfaction.

Effect of diversity on trust

The team’s diversity involves functional and cultural diversity, language barriers, team members’ problem-solving approach, and time differences and holidays for virtual project teams. According to the literature, diversity of team members is negatively associated with the development of trust. Stated that diversity among team members could cause variations in their attitudes, values, and overall performance, perhaps giving rise to conflicts when team members interact [61]. Found that since cultural diversity increases the complexity, conflict and confusion, it sets higher challenges for leaders and members [69]. Cultural and language differences result in miscommunication, which jeopardised trust, cohesion, and team identity. When team members fail to adapt to foreign cultures and disputes or problems remain unsolved, they blame other team members [70]. If this occurs, problems pertaining to the coordination of virtual team activities, creating expectations, building trust, and the ability to learn from various cultures will abound [71]. Functional diversity involves a range of functional assignments being carried out by teams during their tenure. It is believed that functional diversity is associated with differences of opinion and perspective, and it is possible that these differences may result in less effective performance [5].

Contrary to some of these assertions, the participants suggested that in the Middle East, functional diversity actually increases teams’ efficiency and hence increases the confidence of team members to trust each other. This is being validated by the comments of the interviewees discussed as follows.

According to the experience of interviewee AS, he said that “I could see the reason that maximum percentage of people working in virtual project teams is non-local. They are working here from other countries. And they are here for basically to earn money and have a better lifestyle. The guy who works in a country other than his native country always fears losing his job. In order to survive here, he works hard and puts in extra effort to meet the project role and requirements. Even though individuals’ work ethics, cultures, and background are different, their goal is to excel no matter how diverse the teams are.” PR and KO are of the view that “In this region, people come from different countries and with varied nationalities. But when they come here, they all know that they would meet such team members, and in a way, they are ready and mentally prepared to face the diversity. This preparedness not only helps them to adjust faster with their team but also to develop trust with their trust mates.”

RO and RL believed that “In the construction sector, we find great diversity in teams, diversity in the way the team members approach a problem. And this gives team members different ideas to approach a particular problem giving them alternate solutions for a problem.” RA and VI indicated that “People from different nationalities come here and people believe that the language would be a major concern. But the work mostly done here is in English.” They further stressed that even when the company recruits people, they see that they understand and speak English. So the language is not a problem in Middle East. NA and RA stressed that Diversity brings in lot of experience from different countries. As the people have to work in the same project, the team members’ experience not only helps each other but also develops an interest in knowing new things from other person’s experience.”

Hence, diversity brings in a lot of positivity in building trust as far as the Middle East is concerned. The cultural and functional diversity helps in sharing the varied experiences of the members and helps in increasing the productivity of the teams. Also, the language and time zone is never considered a hindrance in the Middle East.

Effect of team member characteristics on trust

The respondents identified team member characteristics as another factor that affect trust building in VPTs in the construction industry. This factor aligns more with the affect-based trust because it addresses the feelings and emotions, thus tends to be more personal [31]. In some relationships, trust is only dependent on simple essential variables. As relationships mature and members get to know each other, individuals learn to trust or distrust the team members according to their characteristics [29]. The team member characteristics involve ability, integrity, benevolence and propensity to trust. Benevolence is the willingness of a party to benefit another. Ability is the belief in the trustee’s ability or skills to fulfil its obligations as expected by the trustor. Integrity is a party’s expectation that another consistently relies on socially accepted principles of behavior [72]. For effective VPT development and coordination, there is a need for greater awareness of the differing characteristics of the specific members represented on the team [27].

The interviewee PR suggested that “The team members have different characteristics that affect the trust-building in virtual project teams. The ability, integrity and general willingness to trust others greatly encourage the trust among the team members.” SH and NA are of the view that “everybody will love to have friendship with an honest guy as he will never backstab you. Similarly, if the integrity of the person is intact, then definitely team members would trust him. Then the person with open-mindedness, believes everyone will bring people together.” They also believed that team members may not know each other initially, but as relationships mature and members get to know each other, individuals learn to trust or distrust the team members according to their characteristics. AS suggested that “If you have a team member who is positive towards the team, who is enthusiastic, who is very diligent and who is a team player, it really helps the team.”

Further KA stated that “the virtual teams operate in an environment full of uncertainty. Thus, the trustor has to believe that the trustee has good intentions regarding the relationship even in the absence of any legally binding formal agreement or previous commitment.” KO insisted that “The more competent members in the team, the higher the level of team trust [73]. Similarly, the higher the level of one’s willingness to help and integrity of team members, the higher the level of team trust. Also an honest and dedicated person is trusted more than a cunning fellow.”

Therefore, it is a challenge for a project manager to find out those team members who are not contributing to the expected level and should know how to handle these cases. So, to build trust and to have a successful project, the team members must contribute more towards the goal. Also, the manager’s integrity and zero tolerance to violation of a standard set of ethical principles must motivate the team members to assume responsibility for their decisions and actions and act responsibly.

Effect of leadership on trust

One major thematic category that emerged from data analysis is the need for effective leadership to enhance trust-building in VPTs. According to the literature, leadership in an organization plays a vital role in a team’s success. Team leaders provide coaching and support. They also ensure that the teams are given responsibility, adequate resources and the necessary authority to make decisions and ensure accomplishment of tasks [5,21]. Indicated that the leader should provide continuous feedback, be sensitive to team members’ problems, clearly define responsibilities, exercise authority, and maintain a consistent attitude over the project’s life. The leadership skills of managers play a positive role in increasing the trust among virtual project team [22]. However, the respondents revealed that the leadership skills of managers do not have a significant effect on the development of trust among virtual project team members in the Middle East. The results are validated by taking interviews of team members and team leaders of the construction sector [74]. As per the interviewee PR, “Actually, things here in the Middle East seem to be different than other areas. Team members are constantly being monitored for performance, so whether or not they are encouraged by the project manager, they will still perform as they have to show results for their survival. Therefore, leadership does not matter here.” KO added to this by saying, “I think virtual team members in the Middle East are quite self-driven, focused on their work and concentrating more on target task completion. It does not matter whether or not they are being pushed by a superior.”

RL, RO, RA and NA made a point by saying that “People here in the Middle East have come here to earn and survive as long as possible as the income here is tax-free. People understand that the teams associated with may change in the next project; even their boss or project manager will also change. So the team members still have to show their performance and establish trust irrespective of the motivation of their team leader.” KA insisted that “Under normal projects, leadership matters a lot. But in the context of virtual teams, the superior may or may not be present at all the time; he may be based in a different office and different location. Sometimes it feels that there is nobody to pat on your back when there is some achievement. So, in a virtual context, the leadership of the superior does not matter much. People would still do their job to the best whether or not the boss is there.”

However, two of the project managers interviewed gave a different perspective that having good leaders in a team is crucial. The motivation and support of a leader is very much required for the effective working of teams. SH was of the view, “The teams are shortlived. The initial phase of the team would definitely need a team leader, and members would look only at the team leader for guidance.” However, he also insisted that the team leader is not required at every stage of the project AS stated that leadership is quite important. But it also depends on the kind of projects taken up by virtual teams. If the virtual teams are working more on productive projects where innovation is concerned, and requirement is not project-specific, leadership is not required. But if the project is very specific and unique, then it’s very important to have a good leader.”

Team members rely on their managers to keep them informed of the necessary information and support their activities with effective feedback and recognition. However, in the context of the Middle East, the professionals believed that leadership is not very important as people have come here to earn money, and they do their jobs without even being mentored. This is also primarily because the team members want to stay longer here. As the virtual teams are short-lived, whether or not they have a superior to pat on their back, they need to give their best to be absorbed in another team based on their performance. However, effective leadership role in building trust in VPTs will require a balance between cognition-based trust (i.e. communication/interaction and knowledge) and affect-based knowledge (i.e. being thoughtful and emotional investments). While leadership roles include knowledge management through effective communication and interaction with team members, a leader’s willingness to show care and concern and invest his emotions in the followers demonstrates affect-based trust building.

Effect of task-technology fit on trust

Found that task-technology fit is vital in virtual teams’ life cycle to evaluate the possible fit between various technologies available to virtual teams and the tasks called upon to be completed [5]. It is essential to ensure a fit between the task, the technology, and the work structure that a virtual team is supposed to carry out. Revealed that if virtual team members can adapt the technology and match it to the communication requirements, the virtual teams are more effective [5]. While new technologies for virtual working should be welcomed, backup preparations for any interruptions are also required [55]. Although task-technology fit relates positively to the team’s trust based on the literature, finding from the interview revealed that there is no significant effect of task technology on the trust-building of the virtual project teams in the Middle East. The following discussion proves this.

Discussion

As per the view of the interviewee AS and KA, “The tasktechnology improves the efficiency of the virtual project teams. But it won’t have any effect on trust-building in a virtual team.” They believed that communication within the team has to be strong for bringing trust within the teams. AS and VI added that “In the construction sector, we have various tasks as engineering, procurement, planning and construction. Different software for designing, procurement, inventory management and planning are required. The non-availability does not affect the trust of the team members. Rather they become more focused on getting this software in the team to increase the efficiency of the project.” PR and RL stressed that “Even though at times, the team members do not know the operability of this software, they learn it in due course of time. But at any times, it does not affect their trust-building in anyways.”

Therefore, it is recommended that the organization provide the right technologies for the projects to increase the teams’ productivity as there are different complexities [75]. However, even if the technology is not present for a particular task, the trust among the team members won’t get affected, but there would be a decrease in the teams’ efficiency.

Trust is essential in teams for performance and productivity, regardless of whether team members are virtual or in the same place. Building trust in virtual teams is more difficult than in collocated teams since virtual team members reside in various geographic areas and have few or no face-to-face interactions. This study qualitatively explored factors affecting trust-building in VPTs in the construction sector of the Middle East. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with ten professionals from construction companies in the Middle East. Six themes emerged from the data analysis process of the general question about the challenges of building trust in virtual project teams. The themes include: conflict among the team members; diversity among team members; organisational culture; team member characteristics; cohesion among team members; and communication issues. The result provides a first theoretical approach specifying empirically observed effects of prominent factors (with prior theoretical considerations) on trust building in the domain of VPTs. The qualitative interviews revealed six subcategories of factors affecting trust in VPTs, including organisational culture, communication, diversity, leadership, task-technology fit, and team member characteristics.

Conclusion

The findings from the interviews confirmed that trust is a key factor to effective collaboration in VPTs. Hence, understanding the interdependence between these factors and trust will help virtual team members remain focused on achieving effectiveness and efficiency in their work. This study provides a collection of factors that managers of VPTs may utilize to establish effective interactions among team members in the Middle East. Since virtual teams allow a group of bright, highly-skilled, and experienced individuals distributed across various places to collaborate on specific construction projects without relocating, these factors may be utilized by both members and companies to assess their teams and members thoroughly. The study also offers insight into VPT functioning in the study area, which intending team members can leverage. This study provides a basis for further quantitative studies, in which, among other things, relationships between trust and trust-building elements in VPTs should be investigated. The study is confined to the Middle Eastern construction industry; hence, it cannot be generalized without more research in other countries and regions worldwide. Comparable research in another location or country may reveal different criteria for developing trust in VPTs.

References

- Bhat SK, Pande N, Ahuja V (2017) Virtual team effectiveness: An empirical study using SEM. Procedia Comput Sci 122: 33-41. Â n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Choi OK, Cho E (2019) The mechanism of trust affecting collaboration in virtual teams and the moderating roles of the culture of autonomy and task complexity. Comput Hum Behav 91: 305-315.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Gibson CB, Gibbs JL (2006) Unpacking the Concept of Virtuality: The Effects of Geographic Dispersion, Electronic Dependence, Dynamic Structure, and National Diversity on Team Innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly 51: 451-495.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Hacker JV, Johnson M, Saunders C, Thayer AL (2019) Trust in virtual teams: A multidisciplinary review and integration. Australas J Inf Syst 23: 1-36.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Hoch JE, Dulebohn JH (2017)Team personality composition, emergent leadership and shared leadership in virtual teams: A theoretical framework. Hum Resour Manag Rev 27: 678-693.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Penarroja V, Orengo V, Zornoza A, Hernandez A (2013) The effects of virtuality level on task-related collaborative behaviors: The mediating role of team trust. Comput Hum Behav 29: 967-974.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Bond-Barnard TJ, Fletcher L, MSteyn H (2018) Linking trust and collaboration in project teams to project management success. Int J Manag Proj Bus 11: 432-457.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Breuer C, Hüffmeier J, Hibben F, Hertel G (2020) Trust in teams: A taxonomy of perceived trustworthiness factors and risk-taking behaviors in face-to-face and virtual teams. Hum Relat 73: 3-34.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Kildiushova T(2021) Building trust in virtual teams. (Doctoral dissertation, Universität Linz).

- Schulze J, Krumm S (2017) The virtual team player: The virtual team player: A review and initial model of knowledge, skills, abilities, and other characteristics for virtual collaboration.. Organ Psychol Rev 7: 66-95.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Cheng X, Yin G, Azadegan A, Kolfschoten G (2016) Trust evolvement in hybrid team collaboration: A longitudinal case study.. Group Decis Negot 25: 267-288.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Charlier SD, Stewart GL, Greco LM, Reeves CJ (2016) Emergent leadership in virtual teams: A multilevel investigation of individual communication and team dispersion antecedents.. Leadersh Q 27: 745-764.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Baralou E, Tsoukas H (2015) How is new organisational knowledge created in a virtual context? An ethnographic study.. Organ Stud 36: 593-620.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Deloitte Denmark (2021) Overcoming virtual leadership challenges during Covid-19. SAccess on 8th August 2021.

- Montoya MM, Massey AP, Lockwood NS (2011) 3D collaborative virtual environments: Exploring the link between collaborative behaviors and team performance.. Decis Sci 42: 451-476.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Garro-Abarca V, Palos-Sanchez P, Aguayo-Camacho M (2021) Virtual Teams in Times of Pandemic: Factors That Influence Performance.. Front Psychol 12: 1-14.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]n

- Hosseini MR, Chileshe N, Baroudi B, Zuo J, Mills A (2016) Factors affecting perceived level of virtuality in hybrid construction project teams (HCPTs): A qualitative study. Constr Innov 16: 460-482.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Cheng X, Bao Y, Yu X, Shen Y (2021) Trust and Group Efficiency in Multinational Virtual Team Collaboration: A Longitudinal Study. Group Decis Nego 30: 529-551.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Katane J, Dube S (2017) The influence of organisational culture and project management maturity in virtual project teams.. Cell 72: 1-10.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Amah E, Nwuche CA, Chukuigwe N (2013) Result Oriented Target Setting and Leading High Performance Teams Ind Eng Le 3: 47-60.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Kaur S (2017) Model for assessment of trust within VPTs of construction sector in the Middle East (Doctoral dissertation, University of Salford).

- Jimenez A, Boehe DM, Taras V, Caprar DV (2017) Working Across Boundaries: Current and Future Perspectives on Global Virtual Teams. J Int Manag 23: 341-349.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Lukić J, Vraćar MM (2018) Building and Nurturing Trust Among Members in Virtual Project TeamsStrateg manag 23: 10-16.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Liao C (2017) Leadership in virtual teams: A multilevel perspective. Hum Resour Manag Rev 27: 648-659. Â n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Gilson LL, Maynard MT, Jones Young NC, Vartiainen M, Hakonen M (2015) Leadership in virtual teams: A multilevel perspective. J Manag Stud 41: 1313-1337.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Zuofa T, Ochieng EG (2017) working separately but together: Appraising virtual proÂject team challenges. Team Perform Manag: Int J 23: 227-242.

- Â Pelsmaekers K, Jacobs G, Rollo C (2014) Trust and discursive interaction in organisational setings. In Pelsmaekers K, Jacobs G, Rollo C (Eds), Trust and Discourse: organisational perspectives (pp. 1-10). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Dietz G, Gillspie N, Chao GT (2010) Unravelling the complexities of trust and culture. In Saunders MNK, Skinner D, Dietz G, Gillspie N, Lewicki RI (Eds.), Organizational Trust: A Cultural Perspective. UK: Cambridge University Press.

- McDermott P, Khalfan M, Swan W (2005) Trust in construction projects. J Financ Manag Prop Constr 10: 19-32. Â n[Google Scholar]n

- Wong WK, Cheung SO, Yiu TW, Pang HY (2008) A framework for trust in construction contracting. Int J Proj Manag 26: 821-829.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Lewis JD, Weigert A (1985) Trust as a social reality. Soc Forces 63: 967-985.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Meyerson D, Weick KE, Kramer RM (1996) Swift Trust and Temporary Groups.. In R. M. Kramer & T. R. Tyler (Eds.), Trust in organisations: Frontiers of theory and research (pp. 166–195). Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications, Inc.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Salas E, Burke CS, Cannon-Bowers JA (2000) Teamwork: Emerging principles.. Int J Manag Rev 2: 339-356.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Townsend AM, DeMarie SM, Hendrickson AR (1998) Virtual Teams: Technology and the Workplace of the Future. The Acad Mgmt exec 12: 17-29.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Chen TY, Chen YM, Chu Ch (2008Developing a trust evaluation method between co-workers in virtual project team for enabling resource sharing and collaboration. Comput Ind 59: 565-579.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Kaur SS, Arif M, Akre VL (2015) Factors affecting Trust in Virtual Project Teams in Construction Sector in Middle East. in 12th Post-Graduate Research Conference 2015, Media City U.K, 10-12 June 2015, pp 262- 276.

- Lee-Kelley L, Sankey T(2008) Global virtual teams for value creation and project success. Int J Constr Proj Manag 26: 51-62.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Lurey J, Raisinghani MS (2001) An empirical study of best practices in virtual teams. Inf Manag 38: 523-544. Â n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Cascio WF (2000) Managing a virtual workplace. Acad Manage exec 14: 81-90.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Munkvold B, Zigurs I (2007) Process and technology challenges in swift- starting virtual teams. Inf Manag 44: 287-299.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Peters LM, Manz CC (2007) Identifying antecedents of virtual team collaboration. Team Perform Manag 13: 117-129.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Sarker S, Valacich JS, Sarker S (2003) Virtual team trust: Instrument development and validation in an IS educational environment. Inf Resour Manag J 16: 35-55.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Dani S, Burns ND, Backhouse CJ, Kochhar AK (2006) The implications of organisational culture and trust in the working of virtual teams. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part B: J Eng Manuf 220: 951-960.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Jones TM, Bowie NE (1998) Moral hazards on the road to the “virtual†corporation. Bus Ethics Q 8: 273-292.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Sarker S, Valacich JS, Sarker S (2003) Virtual team trust: Instrument development and validation in an IS educational environment. Inf Resour Manag J 16: 35-55. n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- McDonough EF, Kahnb KB, Barczaka G (2001) An investigation of the use of global, virtual, and colocated new product development teams.. Journal of Product Innovation Management: Int J Prod Dev Manag Assoc 18: 110-120.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Sarker S, Lau F, Sahay S (2000) Using an adapted grounded theory approach for inductive theory building about virtual team development.. ACM SIGMIS Database: Data Base Adv Inf Syst 32: 38-56.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Modeling team efficiency for international production assignments in Chinese manufacturing multinationals

- Buvik MP, Rolfsen M (2015) Prior ties and trust development in project teams–A case study from the construction industry. Int J Constr Proj Manag 33: 1484-1494.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Henderson LS, Stackman RW, Lindekilde R (2016) The centrality of communication norm alignment, role clarity, and trust in global project teams.. Int J Constr Proj Manag 34: 1717-1730.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Yalegama S, Chileshe N, Ma T (2016) CCritical success factors for community-driven development projects: A Sri Lankan community perspective.. Int J Constr Proj Manag 34: 643-659.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Rutz L, Tanner M (2016) Factors that influence performance in global virtual teams in outsourced software development projects. In 2016 IEEE International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Innovative Business Practices for the Transformation of Societies (EmergiTech) 12: 329-335.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Adams J, Khan HTA, Raeside R (2014) Research methods for business and social science students. 2nd ed.) Los Angeles CA: Sage Publications.

- Zuofa T, Ochieng EG (2021) Investigating Barriers to Project Delivery using Virtual Teams.. Procedia Comput Sci 181: 1083-1088.n[Crossref]Â [Google Scholar]n

- Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L (2006) Investigating Barriers to Project Delivery using Virtual Teams.. Field methods 18: 59-82.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Owonikoko EA (2016) Building and maintaining trust in virtual teams as a competitive strategy (Doctoral dissertation, Walden University).

- Bell E, Bryman A, Harley B (2018). Business research methods. 5th ed. Oxford university press.

- Efimov I, Harth V, Mache S (2020) Health-oriented self-and employee leadership in virtual teams: a qualitative study with virtual leaders. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17: 1-20.

- Kwaye AS (2018) Effective Strategies for Building Trust in Virtual Teams (Doctoral dissertation, Walden University).

- Lipnack J, Stamps J (1997) Virtual teams: Opportunities and challenges for e- leaders, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York.

- The mechanism of trust affecting collaboration in virtual teams and the moderating roles of the culture of autonomy and task complexity.

- Malhotra A, Majchrzak A (2014) Enhancing performance of geographically distributed teams through targeted use of information and communication technologies. Hum Relat 67: 389-411.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Hansen DE (2016) Cohesion in online student teams versus traditional teams. J Mark Educ 38: 37-46.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Shachaf P (2008) Cultural diversity and information and communication technology impacts on global virtual teams : An exploratory study. Inf Manag 45: 131-142.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Chang HH, Hung CJ, Hsieh WH (2014) Cultural adaptation, communication quality, and interpersonal trust. Total Qual Manag Bus Excell 25: 1318-1335.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Han SJ, Beyerlein M (2016) Framing the effects of multinational cultural diversity on virtual team processes. Small Group Res 47: 351-383.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Mayer RC, Davis JH, Schoorman FD (1995) An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust. The Acad Mgmt Rev 20: 709-734.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- McDermott P, Khalfan M, Swan W (2005) Trust in construction projects. J Financ Manag Prop Constr 10: 19-32. Â n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- McDonough EF, Kahnb KB, Barczaka G (2001) An investigation of the use of global, virtual, and colocated new product development teams. Journal of Product Innovation Management: Int J Prod Dev Manag Assoc 18: 110-120.n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

- Owens D, Khazanchi D (2018) Exploring the impact of technology capabilities on trust in virtual teams. Am J Bus 33: 157-178. n[Crossref] [Google Scholar]n

Citation: Sagar SK, Arif M, Oladinrin OT, Rana MQ (2021) Exploring Factors Affecting Trust in Construction Virtual Project Teams. J Archit Eng Tech 10: 254.

Copyright: © 2021 Sagar SK, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 2458

- [From(publication date): 0-2021 - Apr 21, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1954

- PDF downloads: 504