Explanation of Genesis, Continuity and Change of Policy: Analytical Framework

Received: 23-Jan-2014 / Accepted Date: 23-Feb-2015 / Published Date: 26-Feb-2015 DOI: 10.4172/2090-5009.1000115

Abstract

In face of linked dynamics of society and nature as well as social, technological and Ecological transformation processes, a shift towards pathways of sustainable development is needed. This challenges societies to establish new forms of governance. Innovation of governance has to be based on an understanding of contemporary governance and specific policies in relation to the named broader processes of transformation in order to explore possible future pathways of governance change. To generate such an understanding a genealogy of particular policies is necessary. This article presents conceptual and methodological grounds to study the genesis, continuity and dynamics of policies through time and space. It presents an analytical and methodical framework which fits for the analytical reconstruction of policies' historical pathways of development in order to understand processes of generation, stabilization and change. Such a purpose requires some stock-taking with respect to different concepts and strands of empirical research that underlie the particular perspectives and approaches of the analytical framework. Furthermore, it presupposes the theoretical and conceptual positioning of the elaborated analytical approach.

Keywords: Historical neo-institutionalism; Genesis; Analytical framework; Policy paths

17716Introduction

In face of linked dynamics of society and nature as well as social, technological and ecological transformation processes, a shift towards pathways of sustainable development is needed. This challenges societies to establish new forms of governance. Innovation of governance has to be based on an understanding of contemporary governance and specific policies in relation to the named broader processes of transformation in order to explore possible future pathways of governance change. To generate such an understanding a genealogy of particular policies is necessary.

This article presents conceptual and methodological grounds to study the genesis, continuity and dynamics of policies through time and space. It presents an analytical and methodical framework which fits for the analytical reconstruction of policies’ historical pathways of development in order to understand processes of generation, stabilization and change. Such a purpose requires some stock-taking with respect to different concepts and strands of empirical research that underlie the particular perspectives and approaches of the analytical framework. Furthermore, it presupposes the theoretical and conceptual positioning of the elaborated analytical approach.

But before the latter is introduced, several requirements for the analytical framework should be defined to meet its objective to precisely differentiate and explain the emergence, continuity and (gradual or fundamental) change of policy:

• It should consider the process dimension of policy, i.e., the temporal sequencing and timing of important events including a greater historical-political context, to explain empirical phenomena.

• It should comprehend the mutual influence of structures, actors and discourses.

• It should conceptually capture both continuity and change of policy, based on the preliminary assumption that these are the two sides of the same coin.

• It should provide an appropriate set of analysis tools to identify and clearly distinguish between genesis, continuity and change of policy.

• It should assume that changes of policies and/or on the level of actors and discourses can be induced exogenously as well as endogenously.

This article is structured as follows: First of all, the two strands of the analytical framework as well as some of their concepts and analysis tools will be introduced. In this context it will be discussed, how far they meet the formerly defined requirements. Afterwards, a methodology will be outlined that shows how to empirically study the processes by which policy is unfolded, the constellations from which policy emerges and the institutions, actors, and discourses by which policy is brought about and shaped. The final chapter summarizes key findings of the paper and offers suggestions regarding further research.

Policy Analysis And Path Dependence

Historical neo-institutionalism

The historical neo-institutionalism (HI) seems to meet most of the mentioned requirements and therefore will be integrated into the analytical framework. In contrast to the sociological or rational choice neo-institutionalism [1-4], this approach analyses the interdependencies between actors and institutions while taking the historical developments into account [3]. Based on a quite broad concept of institutions [1,5], these and actors’ individual actions are understood as constituting and mutually influencing. In addition, it is assumed that institutions cause disparate power relations [1,6].

While the determining feature of HI initially was “to place a historical perspective at the center of […] research” [7], recent studies integrate political processes into their broader historical-political contexts to explain empirical observations. It is assumed that without such integration, the political processes as well as important impact factors would be ignored [8].

Path dependence: concept and model

The approach of “placing politics in time” (ibid.: 2) focuses on the concept of path dependence. Indeed, there are partially very different modes of explanation within the scope of this concept while a coherent depiction is missing. In general, a distinction between a broader and a narrower conception can be identified. The former means” that what happened at an earlier point in time will affect the possible outcomes of a sequence of events occurring at a later point in time” [1,9,10]. Meanwhile such a concept of path dependence is not only used for comparative historical studies regarding the development of modern societies; beyond that many studies in political science today acknowledge the importance of history to understand political constellations and events [11-16]. For such a research concern the broader definition of path dependence provides an abstract framework for analysis. However, with its increasing popularity it has progressively lost a specific meaning [14,17]. According to Pierson [8], the concept of path dependence in its reduced history-matters-variant therefore has insufficient explanatory power. To nevertheless use its analytical potential while avoiding the danger of “concept stretching” (ibid.), he argues for a more consistent application of path dependence.

The closer definition of path dependence, which is used in this paper, not only implies historical causality, but also characterizes path dependent developments as follows: Structures, which emerged in a curious historical initial configuration, subsequently tend to reproduce themselves [18,19]. With increasing returns actors have strong incentives to focus on a single alternative and to continue down a specific path once initial steps are taken in that direction. The reproduction of institutional transformation processes, which is frequently challenged by unforeseen exogenous events, is caused by self-reinforcing mechanisms [11,14,20,21] that lead to a “positive feedback” between institutions and actors’ behavior [19]. Until a certain point, where change within or even of the path again becomes possible (see below), the path becomes – depending on the ongoing effectiveness of stabilization mechanism – more stable and a change of policy becomes less possible the longer the path is followed. The actors’ sphere of influence then is limited by a predefined development path. Schreyögg and Sydow [14] describe it as follows: “A specific pattern […] gets deeply embedded in practice and replicated across various situations.” Former path choices are therefore only revisable through high energy efforts and expenditures; switching to an initially plausible alternative becomes more and more difficult. Such a situation can be described as locked-in, still leaving however, some scope of variation. Due to the social character of political processes – they are complex and ambiguous in nature – lock-in can be conceptualized as resistance to change that differs from typical lock-in determinism [14,19].

As it is already implied in the conception of lock-in, no policy path lasts forever; all policy paths are susceptible to fundamental change [11,22]. As it is more deeply discussed afterwards, recent works on path dependent policy processes do not argument on the assumption of hyper-stable institutions and irreversible lock-ins, but on that of specific exogenous as well as endogenous impact factors’ and developments’ ability to destabilize an established path and to encourage fundamental change of a path. In the case of the actors’ scope of action concerning change within or of paths, [11] accentuates: “What should be borne in mind is that actors are always capable of finding a key by which to reopen the lock.”

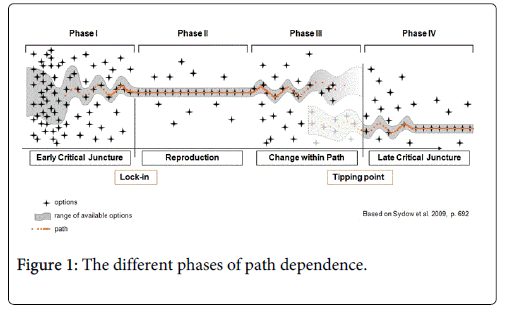

The below presented model (Figure 1) summarizes discussions on self-reinforcing path dependence. It is orientated at Pierson’s studies, but also includes recent insights with special regard to changes within policy paths. As such it represents a dynamized conception of path dependence. The model distinguishes between four phases in the process of bringing about path dependence:

Early critical juncture

• At the beginning several alternatives have to be at choice (multiple equilibria) [19]. This preformation period is to a certain degree influenced by the past and can be characterized by a broad scope of action [14].

• The path is initiated by a more or less contingent event (initial choice) at a critical point in time [19]. The specific historic-political configurations, actors’ decisions (formative choices) as well as coincidences and unpredictable events (contingency) during this formation period are translated into a more or less stable policy path [2,23].

Reproduction

• Once the path is initiated, increasing returns appear and highlight positive feedback. Both, increasing returns and positive feedback, indicate that self-reinforcing processes are set into motion. These lead to a progressively stable path [19,24].

• Due to the importance of timing and sequencing, little events are able to cause great effects and vice versa great events can have just little impact, because “when things happen in a sequence (it) affects how they happen” [25].

Changes within the path

• During the third stage, the path’s self-reproductive balance comes out of equilibrium due to qualitatively new exogenous and/or endogenous impact factors or developments, respectively. Changes occur, but solely within the path [11,26].

Late critical juncture

• Finally, the path’s equilibrium becomes intermitted at a critical point (tipping point) again [19].

• The introduced path dependence model will be the foundation of subsequent discussions in this paper as the following sections will discuss its different phases in further detail. This will be done in order to elaborate the analytical power of the dynamized path dependence conception.

Genesis And Reproduction Of Paths

Early critical juncture

To differentiate between critical junctures and noncritical junctures it is important to define the former precisely. Another important requirement for a definition of critical junctures is the fact that conditions for their occurrence have to be accomplishable because otherwise the necessary explanatory power of analysis is missing. Thelen [26] appropriately suggests that those conditions contributing to the emergence of a policy path do not have to be the same as those that lead to its termination. Against this background, this study follows the literature that distinguishes between early critical junctures (periods of path formation) and late critical junctures (periods of path termination).

Paths start during early critical junctures as a consequence of more or less conscious formative choices [2] by collective actors in a historical situation [27]. During early critical junctures significant institutional and political parameters are negotiated and established. Those fix the politically feasible and imaginable and thereby form political decision making of the following years which then can hardly be changed [8,28]. Moreover, an early critical juncture typically occurs in different ways and produces distinct legacies in various countries (or in other units of analysis) [23].

Therefore, origins of political paths or institutional arrangements cannot be deduced solely from current institutional functions and contemporary conditions [4,19,26]. Focusing on actors’ scope of action, Bo Rothstein [29] explains the interest of historic neo-institutionalists in early critical junctures as follows:

”If institutions set limits on what some agents can do, and enable other agents to do things they otherwise would have not been able to do, then we need to know under what circumstances these institutions were created. If political agents can design or construct institutions, they may then construe an advantage in future political battles.“

The choice of path thus is the result of the prevailing structures and power constellations in relevant institutions which are present during a "window of opportunity for action" [27,30]. This window of opportunity could but does not have to be opened up by a political conflict or a societal crisis situation [27].

Similarly, the policy cycle model of policy research postulates that the formative period has a defining effect on the subsequent phase of implementation [31,32]. Due to its compatibility with the model of path dependence within HI, the period of early critical juncture can also be ideal-typically differentiated in the phase of problem definition and agenda setting and policy formulation. This shall be considered in this study, too.

Reproduction

With regard to continuity and consequent stability of policy paths, various studies within HI identify contexts in which self-reinforcing mechanisms are effective and contribute significantly to an increasing stability of paths. Pierson [19] understands political processes as contexts which can foster self-reinforcing path dependence due to its following characteristics: (1) the high significance of collective action, (2) the high density of institutions, (3) the possibility of increasing power asymmetries and (4) the immanent complexity and opaqueness. Due to the last-mentioned feature Pierson himself considers the understanding of the political world as receptive to path dependencies (ibid.: 260). To explain path dependent actions in complex decision making situations he refers to findings of cognitive psychology and organizational theory: Actors operating in high complex and opaque environments process new information in terms of existing “mental maps” whereby the information that confirms existing orientation patterns can easier be incorporated than contradictory [20,33]. Hence, Pierson [19] concludes that even interpretations of political decision making underlie positive feedback mechanisms. Solely the necessity to use mental maps induces self-reinforcing processes which become apparent, e.g., in the formation of discourse communities that share and reproduce similar world views. Once established, fundamental perceptions of politics prove to be resistant and hence path dependent [34].

Thus, to state assumptions on stability of policy paths (dependent variable) the mentioned particular characteristics of political processes can be integrated into the analysis as the independent variable. The particular manifestation of the latter, as a consequence, allows conclusions concerning susceptibility for change.

Moreover, timing and sequencing of certain events is of particular relevance. Three central assumptions can be identified that have to be considered when examining the genesis and unfolding of political processes. First of all, Pierson [8] underlines that “temporal ordering of events or processes has a significant impact on outcomes”. This is due to the fact that small and accidental early events can have a strong impact on the assertion of an alternative, as they are able to activate mechanisms that reinforce a once chosen path of development. This substantially changes the results of events or processes that occur at a later point of time (ibid.: 12).

He furthermore states that the impact of an event often depends on the certain moment in a sequence in which it occurs.

Finally, in respect of timing it is assumed that an early control of specific policy fields or “political spaces” [35] may generate competitive, eventual self-reinforcing advantages [18]. Anyhow, this presupposes the compatibility of forms of organizations and political context as well as the ability of actors to use their opportunities for action [36]. The herein posed argument of an early control of political spaces coincides with the ahead stated self-reinforcing effect of an early power bias. This leads to the hypothesis that the possibility of intervention in political decision making for challenging actors correlates with the degree of stability of a policy path: The more stable a policy path is, the more difficult it is for actors to challenge established formations.

According to critics of arguments on sequencing and timing [37], these should be taken into consideration analytically but should neither be applied mechanistically, nor serve as an exclusive explanation factor.

Research findings regarding self-reinforcing mechanisms show how stable policy patterns emerge and subsist [4]. For such a focus the presented model of path dependence constitutes an appropriate analysis instrument in comparative policy research. Additionally, the specific characteristics of self-reinforcement provide insights into the complex interdependence of stability and change within political processes that could help to enlighten those developments that finally lead to a change of policy paths [4,8].

Changes Within And Change Of Paths

For a long time the path dependence concept in general was associated with a long-lasting stability and therefore blamed for its insufficient explanatory power regarding policy changes [2,4]. As already mentioned above, more recent works within HI argue that the prevailing concept of path dependence overstates the degree of stability of political processes or institutions and for this reason endeavor to open or dynamize it [8,11,15,16,22,26,38]. Those factors and mechanisms that lead to change within or of policy paths (late critical junctures) come to the fore. Consequently, not only exogenous impact factors (such as events, constellations or random influences, respectively) are considered but in addition to it endogenous explanation patterns and thus also actors’ options to press for and initiate gradual and incremental or abrupt change. Path dependence as conceptualized in these studies hence contains both elements of continuity as well as those of (fundamental) change. Such a dynamized conception of path dependence has already been integrated in the presented path dependence model and will be advanced in the following chapters in order to meet analytical framework’s objective to exactly differentiate and explain genesis, continuity and (gradual or fundamental) change of policy. The intention of this study to link the analysis of policy with that of path dependence in this respect promises an important insight [39].

Change of paths

Historical institutionalists typically tried to explain fundamental institutional change by using the idea of “punctuated equilibrium”. According to the idea of “punctuated equilibrium” an institution or policy is in a stable state of equilibrium for a long time. In this period of stasis it functions in accordance with former decisions during its foundation or former phases of “punctuation”. The latter take place in times of severe historical crises, caused by exogenous shocks or a shift in the environment. In these situations fast and sudden changes of policies or institutions occur [40]; thus they considered change as solely induced by exogenous developments. In opposite to this constricted conception, publications in the recent past like that of Thelen [41] argue that institutional change could equally be caused by endogenous processes: “Institutions rest on a set of ideational and material foundations that, if shaken, open possibilities for change“. Based on these insights that (radical) change of institutions – which can culminate in its erosion – is rarely initiated only by exogenous developments but also by creeping incremental endogenous changes, Thelen [26] identifies two mechanisms which force a gradual change of political institutions: “institutional layering” and “institutional conversion”. The mechanism of “institutional layering” comprises “the partial renegotiation of some elements of a given set of institutions while leaving others in place” (ibid.: 225). Subsequent to the research of Deeg [42] and also Eric Schickler [43], she understands coalition formation by political actors as an important driver of institutional development. However, although new political coalitions are able to create new structures they are incapable of replacing established maintenance-orientated institutional arrangements due to, e.g., a lack of support and an inability to mobilize. Therefore, in the layering process additional structures or rules are added on existing institutional systems [26,43]. Each additional layer merely constitutes a small change of institutions but over time institutional layering erodes self-reinforcing mechanisms of a policy path and can transform the fundamental nature of institutions [8].

Thelen [26] refers the mechanism of “institutional conversion” to situations in which “existing institutions are redirected to new purposes, driving changes in the role they perform and/or the function they serve“. This means that a change of actor constellations can as well fundamentally change the nature of an institution without calling the institution itself into question [11]. Such reorientation is either driven by actors that originally created institutions, or by actors that formerly operated beyond or at the periphery of the institutional system [8,26]. In both cases the proceeding institutional conversion is destabilizing the established policy path.

In a later work with Wolfgang Streek, Thelen identifies three additional mechanisms that creepingly destabilize paths [44].

• Institutional “displacement” means the rising salience and importance of subordinate institutions due to increased incoherence of existing institutions.

• Institutional “drift” is a form of erosion of institutions that results from so-called “non-decisions”, i.e., the neglect to update institutional arrangement in face of exogenous pressures.

• Institutional “exhaustion” refers to the gradual breakdown or depletion of institutions over time caused by self-consumption, decreasing returns and overextension.

These insights regarding institutional change should be integrated into the conception of late critical junctures which indicate the end and replacement of a policy path [8,45,46]. In the terminology of policy research, a late critical juncture signifies the redefinition of a problem or the re-evaluation of an implementation, i.e., a change of the policy approach. The following characteristics of late critical junctures can function as analysis criteria to identify changes of policy paths:

• Long-lasting and fundamental change of relevant institutions. This implies that the constellation of power is shifted in favor of previously challenging political actors and actors’ coalitions; the existing institutions pursue essentially different objectives than in the past due to institutional conversion or other mechanisms and/or new institutions with new objectives are/have been created.

• Long-lasting and fundamental change of policies. This implies that political measures, e.g., passed laws or adopted programs, and positioning of key policy makers bear witness to a political reorientation.

Late critical junctures can be caused by:

Exogenous shocks, e.g., a global economic depression, which catalyze a long-lasting fundamental change of institutional arrangements [8]. The new conditions erode or destroy the specific mechanisms that contributed to a reproduction of the established policy path [4]. The end of a path then appears as “a radical system change, when everything is built de novo“[27].

Gradual change that leads to a late critical juncture (change of a path) if change processes reach a so-called “tipping point” [8,42]. Among others, Pierson [8] refers to threshold-effects in policy paths since the effect of certain change processes stays moderate as long as such a tipping point is reached (although it may not be reached). Minor or slightly bigger exogenous and/or endogenous events can have a catalyzing effect, i.e., they contribute to the achievement of a tipping point. The successive change is characterized by gradual stabilization of a new path and weakening of the old path [8,42]. The following institution-related processes often proceed simultaneously: layering, conversion, displacement, drift and/or exhaustion.

Such analyses are frequently criticized because a late critical juncture can merely be identified ex post. Indeed, the reconstruction of political processes is only feasible in retrospect. Similarly, conclusions concerning developments that result in a late critical juncture or contribute to its triggering can solely be drawn ex post. Furthermore, influences are identifiable which during critical junctures catalyzed the realization of a certain alternative [10]. Therefore, ex-post explanations are an important and legitimate concern of policy analysis because they contribute to a better understanding of dynamics of political processes.

Changes within paths

This section extracts analysis criteria from literature that indicate changes within paths. These should be understood as necessary though not sufficient preconditions for a change of a policy path (late critical juncture) that is initiated by the achievement of a tipping point as a result of gradual change processes. Thus, identifying these factors does not necessarily mean that a change of path finally occurs because if and when a tipping point is finally reached cannot be predetermined. But what can be stated is that if those indicators cannot be detected, a change of a path is unlikely. A change within a path corresponds to an evaluation of implementation in policy research which is an important precondition (but no guarantee) for the redefinition of a problem and a change of the policy approach.

Change processes within policy paths can be initiated and pushed by three main groups of actors:

Marginal (groups of) actors

Historical neo-institutionalists point out the role of former “losers” as catalysts for institutional change. Clemens and Cook [47], e.g., state: “Groups marginal to the political system are more likely to tinker with institutions. […] Denied the social benefits of current institutional configurations, marginal groups have fewer costs associated with deviating from those configurations“. The mechanism of institutional conversion likewise bases on the fact that former marginal (groups of) political actors effectively transform institutions’ objectives due to changed circumstances and basic conditions [26].

Entrepreneurs and skilled actors

Entrepreneurs [43] or skilled actors (Stone Sweet et al. [48] are widely accepted as having a key role in mobilizing for institutional reforms. Since these actors actively mediate different interests regarding conceptual development of reform proposals, they are able to motivate other actors to participate in these processes [8].

New political coalitions and networks

According to Schickler [43], those initiatives are particularly assertive that are able to bring down different and sometimes contrary interests and interpretations of problems to the least common denominator and thus enable formation of local political coalitions. In that case, institutional change is usually a negotiated one. The formation of political coalitions is typically promoted by those actors that belong to different social networks (ibid.: 136f.). Following Schicklers findings, Thelen [26] emphasizes the foundation of new political coalitions as a central element of the mechanism of institutional layering [42]. Likewise attributes an important role to political coalition building during the successive establishment of new paths.

These findings of literature can be translated into the following analysis criteria that indicate changes within policy paths:

• Formerly marginal (groups of) political actors become effective challengers

• new political actors as well as skilled actors appear within and beyond the institutional system

• new networks are established beyond the institutional system

• new political coalitions emerge within the institutional system

These indicators of change within policy paths imply a graduation concerning the stability and the potential of efficacy. They hence should help to draw a more differentiated picture of change processes.

Discourse approaches are the second theoretical and conceptual perspective taken into consideration in this study. The following chapter discusses the reasons for an integration of different kinds of discourse approaches into the analytical framework.

Discourse Approaches

With awareness of the requirements for the analytical approach which were defined at the beginning as well as mentioned blurs and conceptual gaps of HI, an integration of discourse approaches into the analytical framework can be justified as follows:

Research within HI usually does not consider the level of discourse although policy research began to acknowledge that discourse matters as a result of the argumentative turn announced by Fischer and Forester [49] at the beginning of the 1990s. For the analysis of institutions, Vivien A. Schmidt [50,51] initially underlined the impact and explanatory power of discourses with regard to continuity and change of policies. Nevertheless, solely a few studies followed this approach [37]. In her latter works, Schmidt [52-54] develops the idea of a “discursive institutionalism” (DI) – epistemologically equivalent to the other variants of neo-institutionalism – in order to explain political continuity and dynamics of change. This approach according to Schmidt [54] considers the discourse of actors within the process of generation, reflection and legitimization of ideas concerning political action in institutional contexts. With the same motivation this study complements the analysis of policies and path dependence with the analysis of discourses. Similar to Schmidt it does not regard discourses as the only explanatory moment concerning continuity or change of policy but rather argues for an equal consideration of traditional variables of policy analysis, e.g., institutional structures. The latter can be altered by discourses, but do not have to. Conversely, institutional arrangements shape discourses, affecting where discourse matters by establishing who talks to whom about what, where and when (ibid.: 20). Discourse, just as any other factor, sometimes does, and sometimes does not matter in the explanation of continuity or change.

The paper’s intention is to reconstruct and to explain both continuity and transformation processes within and beyond political institutional arrangements by analyzing events, political measures as well as problem interpretations, actions and interests of actors and their coalitions/groups, characteristics of discourses and its dynamics as well as institutional contexts and historic-political development paths in their interplay. According to the dynamized concept of path dependence in this study, genesis, continuity and change of policy belong to a historical pathway – discourse is an integral part of this process and is uncovered by means of discourse analysis.

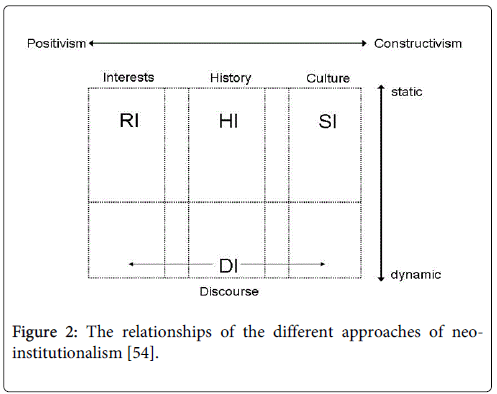

Insofar, the theoretical and conceptual location of the chosen analytical approach between historical and discursive institutionalism seems reasonable. Thus, the approach is located in the middle of the figure presented by Schmidt [54] that facilitates a positioning of the different neo-institutionalisms along a horizontal continuum from positivism to constructivism and a vertical continuum from static to dynamic (Figure 2; the dotted lines represent border areas):

Figure 2: The relationships of the different approaches of neoinstitutionalism [54].

The integration of discourse analytical approaches into the analysis framework should moreover contribute to an extension and refinement of analysis instruments in a way that they become more sensitive to different degrees of rebuilding policy paths and gradual changes. What may appear as continuity on the institutional level, e.g., with regard to distribution of power in institutions can already be set in motion on the discourse level within or beyond institutional arrangements, e.g., new interpretative patterns can enter the social knowledge resources. A differentiated description and explanation of the inner functioning of stagnating, reform-orientated policy paths or those in state of upheaval is thus viable.

Regarding the paper’s concern, it seems to be useful to for the first time relate the sociology of knowledge approach to discourse of Reiner Keller [55-57] to the argumentative discourse analysis of Maarten Hajer [58-62]. These theoretically and conceptually compatible discourse approaches [15] well complement each other with regard to their objects of research and research perspectives in order to fill the analytically relevant gaps of HI. The sociology of knowledge approach to discourse allows an analysis and theory-driven interpretation of micro-dynamics of discourses. In addition, it provides the theoretical background to precisely examine broader social transition processes in which discourses are embedded in [55]. Finally, the approach exposes types of key events that are able to generate discourses, necessary societal conditions for the latter and its effects (ibid.: 274ff.).

The argumentative discourse analysis is the most frequently cited conceptual offer to realize discourse analysis in political science [63] as it focuses especially on interrelations of discourses, strategic behavior of actors and institutional patterns. In particular, it analyses interrelations with the potential to trigger political change [62]. Thus, the argumentative discourse analysis integrates the institutional dimension and affords a link to traditional institutions’ analysis.

To evaluate the influence of a new discourse, [59,60] presents two conditions for its dominance: (1) A discourse dominates the discursive space; that is, central actors are persuaded by or forced to accept the rhetorical power of a new discourse (condition of discourse structuration). (2) This is reflected in the institutional practices of a political domain; that is, the actual policy process is conducted according to the ideas of a given discourse (condition of discourse institutionalization). These two graded conditions are suitable to function as indicators of change within established policy patterns or change of policy paths, respectively; as such they can supplement change indicators of HI.

The integration of these two discourse approaches, policy analysis and conceptions of path dependence within HI into an analysis framework should help to precisely differentiate and explain emergence, continuity and (incremental or fundamental) change of policy. Based on this analytical approach, competing hypotheses regarding the central research question have to be developed and empirically tested. In face of the two theoretical pillars of the analytical approach and the already discussed objects, the theory-driven expectations concern following questions:

Can the implementation of a policy be characterized as a path dependent process and if so, how stable is the path and which self-reinforcing mechanisms are identifiable?

How far do potential critical exogenous and/or endogenous developments induce incremental change within or change of a policy path (late critical junctures)?

Methodology

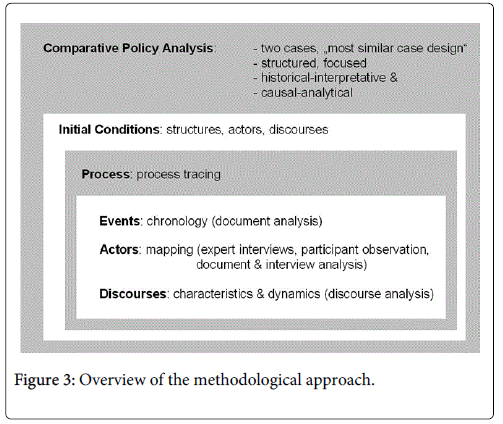

The analytical framework developed in order to meet the named objectives and to cover the different dimensions of policy processes requires an approach based on methodological pluralism. A comparative policy analysis of two cases should be at the centre of research. Regarding the strategy for choosing the cases to be compared the most similar system approach (also: most similar cases design) of Smelser [64] and Sartori [65] could be useful: This logic rests on the ideal-typical assumption that because of homogenous context-related variables there is an exclusive variance of the operative variables. Hence, the independent variables can be used to explain the dependent variables [66]. However, contrary to these ideal-typical assumptions there may be not only context-related similarities but also differences between the selected cases that could affect the policies in research focus. In case empirical testing and discussion of hypotheses do not result in satisfactory answers to research questions, these differences could serve as explaining factors.

The comparative analysis interlocks a historical-interpretative with a causal-analytical perspective. The research focus on policies and their historical pathways of development suggests that process tracing is the method of choice in this case [67]. According to this method, first of all the various phases of the analyzed policy processes have to be identified. In case path dependent developments can be detected, the following step is to ascribe the different phases of the presented path dependence model to the political process: (1) early critical juncture, (2) reproduction of the path, (3) changes within the path and (4) late critical juncture. If the analyzed political processes are not path dependent, the different phases of a policy cycle – not least because of its compatibility with the concept of path dependence – can be applied.

For each of the mentioned phases the following three central process dimensions – also in their interplay – will be analytically reconstructed by various qualitative-interpretative methods: key events and political measures (1), changes on the actors’ level (2) and on the discourse’ level (3). Subsequently, significance and validity of hypotheses will be tested based on empirical findings for each case and finally discussed in a comparative perspective.

The introduced design of the methodological approach – a structured and focused comparative policy analysis with an enlarged spectrum of qualitative and interpretative methods – is summarized in Figure 3. As it is a novelty, its applicability as well as the relationship between the degree of insight and research effort need to be examined carefully.

Conclusions

Sustainable development necessitates new forms of governance that have to be based on an in-depth understanding of contemporary governance patterns and policies. The latter should not be generated solely from current institutional functions and conditions but also from an analysis of its origins and development pathways. The research design introduced here thus focuses on a genealogy of policies in order to explain its genesis, continuity, and (gradual or fundamental) change. To meet this objective, the discussed analytical approach integrates a dynamized conception of path dependence within historical neo-institutionalism, policy analysis as well as discourse approaches – thereby relating the sociology of knowledge approach to discourse of Reiner Keller to the argumentative discourse analysis of Maarten Hajer. This analytical framework first of all enables to conceptually capture both continuity and change of policy, based on the assumption that these are the two sides of the same coin. Furthermore, it allows to address and explain the how and why of continuity and change of policies from an interior view by a set of analysis tools that is more sensitive to different degrees of rebuilding policy paths.

Theoretically, it thus still lies within the scope of historical neo-institutionalism but also refers to theorems and methods of discursive neo-institutionalism. In this way the analytical framework accentuates the mutual compatibility along the borders of these two neo-institutionalisms in favor of a multidimensional explanation of political processes. It is recommended to likewise discuss its relation to other research traditions dealing with continuity and change of policy.

Methodically, the analysis framework requires an approach that is based on methodological pluralism in order to cover the different dimensions of policy processes and their dynamics. A structured and focused comparative policy analysis with an enlarged spectrum of qualitative and interpretative methods seems to be an appropriate methodological design.

Further research should prove the applicability, scope and limitations of the introduced analytical and methodological approach [15]. The elaboration of relevant exogenous as well as endogenous impact factors on policies and of necessary (though not sufficient) preconditions for a change of policies could help to generate ideas how to initiate successful innovation of governance in the sense of sustainable change processes.

References

- Hall PA, Taylor RCR (1996) Political Science and the Three New Institutionalisms. Political Studies 44: 936-957.

- Peters Guy B (1999) Institutional Theory in Political Science. The ‘New Institutionalism’ (London, New York: Continuum).

- Holger S (1997) Neo-Institutionalismus. Ein analytisches Instrument zurErklärunggesellschaftlicherTransformationsprozesse. Arbeitspapiere des BereichsPolitik und Gesellschaft 4/1997 (Berlin: Osteuropa-Institut der FreienUniversität Berlin).

- Thelen K (1999) Historical Institutionalism in Comparative Politics. Annual Review of Political Science 2: 369-404.

- Hodgson GM (2006) What Are Institutions? Journal of Economic Issues, XL 1: 1-25

- Ellen I (1997) The Normative Roots of the New Institutionalism: Historical-Institutionalism and Comparative Policy Studies.In: Arthur Benz, Wolfgang Seibel (eds.) Theorieentwicklung in der Politikwissenschaft - eineZwischenbilanz (Baden-Baden: Nomos), pp. 325-356.

- Margaret W (1992) Politics and Jobs: The Boundaries of Employment Policy in the United States (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

- Paul P (2004) Politics in Time. History, Institutions, and Social Analysis (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

- Sewell, William H (1996) Three Temporalities: Toward an Eventful Sociology. In:Terrance J. McDonald (ed.) The Historic Turn in the Human Sciences (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press), pp. 245-280.

- Renate M (2002) ZurTheoriefähigkeitmakro-sozialerAnalysen. In: Renate Mayntz(ed.)Akteure -Mechanismen - Modelle: ZurTheoriefähigkeitmakro-sozialerAnalysen (Frankfurt/Main, New York: Campus), pp. 7-43.

- Beyer J (2010) The same or not the same – on the variety of mechanisms of path dependence. International Journal of Social Sciences 5: 1-11.

- Koch J, Eisend M, Petermann A (2009) Path Dependence in Decision-Making Processes: Exploring the Impact of Complexity under Increasing Returns. BuR - Business Research 2: 67-84.

- Georg S, Jörg S (2010a) The Hidden Dynamics of Path Dependence (London: Palgrave-Macmillan).

- Georg S, Jörg S (2010b) Understanding Institutional and Organizational Path Dependencies. In: Georg Schreyögg, JörgSydow(eds.) The Hidden Dynamics of Path Dependence (London: Palgrave-Macmillan), pp. 3-12.

- Selbmann Kirsten (2011) Kontinuität und Wandel von Politik. RegulierungGrünerGentechnik in Mexiko und Chile (Baden-Baden: Nomos).

- Sydow J, Lerch F, Staber U (2010) Planning for Path Dependence? The case of a network in the Berlin-Brandenburg optics cluster. Economic Geography 86: 173-195.

- David PA (2007) Path dependence: a foundational concept for historical social science. Cliometrica 1: 91-114.

- Lehmbruch G (2001) Der unitarischeBundesstaat in Deutschland: Pfadabhängigkeit und Wandel. MPIfG Discussion Paper, 02/2. Köln: Max-Planck-InstitutfürGesellschaftsforschung.

- Pierson P (2000) Increasing Returns, Path Dependence, and the Study of Politics. American Political Science Review 94: 251–267.

- Arthur W, Brian (1994) Increasing Returns and Path Dependence in the Economy (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press).

- Mahoney J (2000) Path Dependence in Historical Sociology. Theory and Society 29:507-548.

- Schneiberg M (2007) What’s on the path? Path dependence, organizational diversity and the problem of institutional change in the US economy, 1900–1950. Socio-Economic Review 5: 47-80.

- Collier Ruth B, Collier David (1991) Shaping the Political Arena: Critical Junctures, the Labor Movement, and Regime Dynamics in Latin America (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

- North Douglass C (1992)Institutionen, institutionellerWandel und Wirtschaftsleistung (Tübingen: Mohr).

- Tilly Charles (1984) Big Structures, Large Processes, Huge Comparisons (New York: Russell Sage).

- Thelen Kathleen (2003) How Institutions Evolve: Insights from Comparative-Historical Analysis. In: James Mahoney and Dietrich Rueschemeyer(eds.) Comparative-Historical Analysis: Innovations in Theory and Method (New York: Cambridge University Press), pp. 208-240.

- EbbinghausB (2005) Can Path Dependence Explain Institutional Change? Two Approaches Applied to Welfare State Reform. MPIfG Discussion Paper 05/2, Köln: Max-Planck-InstitutfürGesellschaftsforschung

- Thelen K (2002) The Explanatory Power of Historical Institutionalism. In: Renate Mayntz(ed.)Akteure – Mechanismen – Modelle: ZurTheoriefähigkeitmakro-sozialerAnalysen (Frankfurt/Main: Campus), pp. 91–107.

- Rothstein Bo (1992) Labor Market Institutions and Working Class Strength. In: Sven Steinmo, Kathleen Thelen, Frank Longstreth(eds.) Structuring Politics: Historical Institutionalism in Comparative Analysis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), pp. 33-56.

- Kingdon John W (1995) Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies (Collins, New York: Harper).

- Adrienne WH (1987) Policy-Analyse. EineEinführung (Frankfurt/Main, New York: Campus).

- Barzelay M, Gallego R (2010) The Comparative Historical Analysis of Public Management Policy Cycles in France, Italy, and Spain: Symposium Conclusion. Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration, and Institutions23: 297-307.

- DenzauAD, North DC (1994) Shared Mental Models: Idiologies and Institutions. Kylos 47: 3-31.

- Pierson Paul, Skocpol Theda (2002) Historical Institutionalism in Contemporary Political Science. In: Ira Katznelson, Helen Milner (eds.) Political Science: State of the Discipline (New York: Norton), pp. 693-721.

- Colin C (1986) Sharing Public Space: States and Organized Interests in Western Europe. In: John A. Hall (ed.) States in History, (Oxford: Basil Blackwell), pp. 177-210.

- Thelen K (2000) Time and Temporality in the Analysis of Institutional Evolution and Change. Studies in American Political Development 14: 102-109.

- Scherrer C (2001) Jenseits von Pfadabhängigkeit und „natürlicherAusleseâ€. InstitutionentransferausdiskursanalytischerPerspektive. Diskussionspapier des Wissenschaftszentrums Berlin fürSozialforschung,

- Richard D (2005) Path Dependency, Institutional Complementarity, and Change in National Business Systems. In: Glenn Morgan, Richard Whitley, Eli Moen (eds.) Changing Capitalisms? Internationalization, Institutional Change, and Systems of Economic Organization, (New York: Oxford University Press), pp. 21-52.

- JörgB (2009) Der kanadischeFöderalismus. Einehistorisch-institutionalistischeAnalyse (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag).

- Krasner SD (1984) Approaches to the State - Alternative Conceptions and Historical Dynamics. Comparative Politics 16: 223-246.

- Krasner SD (1988) Sovereignty - An Institutional Perspective. Comparative Political Studies 21: 66-94.

- Deeg R (2001) Institutional Change and the Uses and Limits of Path Dependency: The Case of German Finance

- Eric S (2001) Disjointed Pluralism: Institutional Innovation and the Development of the U.S. Congress (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

- Wolfgang S, Kathleen T (2005) Beyond Continuity: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Pierson P (1996)The path to European integration: A historical institutionalist analysis. Comparative Political Studies 29: 123-163.

- Michael S (1996) Counterfactual Analysis and Path-Dependent Thinking in the Study of International and Comparative Politics (American Political Science Associations Annual Meeting, San Francisco).

- Clemens ES, Cook JM (1999) Politics and Institutionalism: Explaining Durability and change. Annual Review of Sociology 25: 441-466.

- Sweet S, Sandholtz A, Wayne, Fligstein, Neil (2001) The Institutionalization of Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Fischer Frank, Forester John (1993) The Argumentative Turn in Policy Analysis and Planning (Durham, London: Duke University Press).

- Schmidt VA (2001) The Politics of Economic Adjustment in France and Britain: Does Discourse Matter? Journal of European Public Policy 8: 247-264.

- Schmidt VA (2002) Does Discourse Matter in the Politics of Welfare State Adjustment? Comparative Political Studies 35: 168-193.

- Schmidt VA (2008a) Discursive Institutionalism: The Explanatory Power of Ideas and Discourse. Annual Review of Political Science 11: 303-326.

- Schmidt Vivien A (2008b) From Historical Institutionalism to Discursive Institutionalism: Explaining change in comparative political economy. American Political Science Association Meeting, Boston, 28th August 2008.

- Schmidt Vivien A (2010) Reconciling Ideas and Institutions through Discursive Institutionalism. In:Béland D,Robert H. Cox (eds.) Ideas and Politics in Social Science Research (New York: Oxford University Press), pp. 64-89.

- Keller Reiner (2005)Â WissenssoziologischeDiskursanalyse. GrundlegungeinesForschungsprogramms (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag).

- Keller R (2007a)Â Diskurse und Dispositive analysieren. Die WissenssoziologischeDiskursanalysealsBeitragzueinerwissensanalytischenProfilierung der Diskursforschung. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung 8: 19.

- Keller Reiner (2007b) Diskurs/Diskurstheorien. In: Rainer Schützeichel(ed.) Handbuch Wissenssoziologie und Wissensforschung (Konstanz: UVK), pp. 199-213.

- Hajer Maarten A (1993a) Discourse Coalitions and the Institutionalizations of Practise: The Case of Acid Rain in Great Britain. In: Frank Fischer, John Forester (eds.) The Argumentative Turn in Policy Analysis and Planning (Durham, London: Duke University Press), pp. 43-76.

- Hajer Maarten A (1993b) The Politics of Environmental Discourse. A Study of the Acid Rain Controversy in Great Britain and the Netherlands (Dissertation. Oxford University).

- Hajer Maarten A (1995) The Politics of Environmental Discourse. Ecological Modernization and the Policy Process (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

- Hajer Maarten A (2003) Argumentative Diskursanalyse. Auf der SuchenachKoalitionen, Praktiken und Bedeutung.In: Keller R, Hirseland A, Schneider W (eds.) Handbuch SozialwissenschaftlicheDiskursanalyse (Opladen: Leske+Budrich), pp. 272-298.

- Hajer Maarten A (2008)Â Diskursanalyse in der Praxis: Koalitionen, Praktiken und Bedeutung. In: Frank Janning,Kathrin Toens(eds.) Die Zukunft der Policyforschung. Theorien, Methoden und Anwendungen (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag), pp. 211-222.

- Frank N (2001) Politikwissenschaft auf demWegzurDiskursanalyse?.In: Keller R, Hirseland A, Schneider W (eds.) Handbuch SozialwissenschaftlicheDiskursanalyse (Band 1: Theorien und Methoden) (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag), pp. 285-311.

- Smelser Neil J (1976) Comparative Methods in the Social Sciences (Engelwood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall).

- Giovanno S (1984) La polÃtica. Lógica y método en lasCienciasSociales (México: Fondo de CulturaEconómica (FCE)).

- DetlefJ (2006) Einführung in die vergleichendePolitikwissenschaft (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag).

- Gary K, Keohane RO,Verba S (1994) Designing social inquiry: Scientific inference in qualitative research (Princeton: Princeton University Press).

Citation: Selbmann K (2015) Explanation of Genesis, Continuity and Change of Policy: Analytical Framework. Innovative Energy Policies 4:115. doi:Selbmann K (2015) Explanation of Genesis, Continuity and Change of Policy: Analytical Framework. Innovative Energy Policies 4: 115. DOI: 10.4172/2090-5009.1000115

Copyright: ©2015 Selbmann K. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 19196

- [From(publication date): 2-2015 - Apr 16, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 14513

- PDF downloads: 4683