Experiences of Frontline Nursing Staff on Workplace Safety and Occupational Health Hazards in Two Psychiatric Hospitals in Ghana

Received: 02-Apr-2018 / Accepted Date: 06-Apr-2018 / Published Date: 16-Apr-2018 DOI: 10.4172/2329-6879.1000274

Abstract

Background: Psychiatric hospitals need safe working environments to promote productivity at the workplace. Even though occupational health and safety is not completely new to the corporate society, its scope is largely limited to the manufacturing industries which are perceived to pose greater dangers to workers. Purpose: This paper sought to ascertain the occupational health and safety conditions in two psychiatric hospitals in Ghana.

Methods: This is a cross-sectional study among 350 nurses and nurse-assistants in Accra and Pantang psychiatric hospitals using the proportional stratified random sampling technique. Multivariate Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) logistic regression was conducted to ascertain the determinants of staff exposure to occupational health hazards.

Results: Knowledge levels on occupational health hazards were high in the two psychiatric hospitals. Physical health hazards were reported most than psychosocial hazards which are perceived as minor. Frequency of exposure to occupational health hazards was positively associated with work schedules of staff particularly, staff on routine day schedule (Coef=4.49, p=0.011) and those who alternated between day and night schedules (Coef=4.48, p=0.010). Staff age, sex and number of years of work experience were significant correlates of exposure to workplace health hazards (p<0.05).

Conclusion: Occupational health and safety conditions of the two hospitals were found to be generally poor. Reporting of work related health hazards by health staff was low due to low awareness and poor compensations. The Ministry of Health in collaboration with the Mental Health Authority should intensify efforts towards effective enforcement of existing policies on safety in healthcare institutions, particularly psychiatric hospitals.

Keywords: Occupational health; Safety; Psychiatric hospitals; Nurses; Nurse-assistants; Accra; Pantang; Ghana

Background

Every organization needs healthy and safe human resource base for its performance and general productivity. The health sector is no exception given that it is made up of diverse professional groups that are exposed to occupational health hazards at varying degrees. Even though the concept of occupational health and safety is not new to the corporate society, its scope until now was limited to only the manufacturing and processing industries which are perceived to pose greater dangers to workers. The health sector in many resources poor countries in Africa continue to suffer neglect in terms of the attention given to workplace health and safety [1].

However, in some countries in the developed world, occupational health and safety is receiving relatively better attention. For instance, the United States of America (USA) has chalked significant successes through the United States (US) Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA). OSHA has been working at enforcing protective workplace safety and health standards in the US [2].

The International Labour Organization (ILO) and World Health Organization (WHO) Joint Committee on Occupational Health and Safety (JCOHS) in 1995 indicated that occupational health and safety in every work environment entails the promotion and maintenance of the highest degree of physical, mental and social well-being of workers in all occupations [3]. Sadleir [4] specified that occupational health and safety is that aspect of environmental health which entails the interaction between the workplace and the health of the worker. Occupational health and safety is critical for every health system because the health sector is highly labour intensive with health workers constituting a vital input factor in the health service production process.

Moreover, OHS is particularly important in resource poor settings because of limited logistics in many healthcare facilities, particularly psychiatric hospitals where working conditions are worst [5]. These poor working conditions usually compromise health and safety conditions in these healthcare facilities. The situation is often times aggravated by the poor legal foundations on OHS in some countries where physical and psychological violence against healthcare workers is implied to be part of their work [6]. Unfortunately, even countries with stronger legal framework on OHS are victims of this prevalent misconceived attitude towards workplace safety for health workers [7].

This study became necessary because, most work related health hazards in developing settings such as Ghana go unreported [8,9] usually due to ignorance on OHS and poor hospital management systems, particularly in psychiatric hospitals. Moreover, there are not many known scientific publications on occupational health and safety in psychiatric hospitals in Ghana where existing laws on occupational health and safety are obsolete. Thus, it is possible these existing legal provisions are not addressing emerging workplace challenges in psychiatric hospitals. For instance, workplace safety standards in Ghana spelt out in the Workmen Compensation Law (PNDCL 187, 1987) [10] are not being executed to the latter due to poor infrastructure and inadequate human resources at the workplace, including psychiatric hospitals.

Even though mental health conditions account for at least 13% of the global burden of disease [11], this sector continues to suffer neglect and limited attention by governments and health authorities in many countries.

In some publications [12-14] cited by Jack et al. [15], the percentage of health sector budget allocated to mental health is barely 0.5% which translates into approximately 0.007% of Ghana’s GDP. These relatively discouraging statistics appear to explain the poor and unsafe working conditions of psychiatric hospitals in Ghana which have translated largely into low staff motivation levels [15,16].

According to Fulton et al. [17] cited in Jack et al. approximately, 1.18 million additional mental health workers are needed to close the existing mental health treatment gap in low and middle income countries such as Ghana. Moreover, there are approximately eleven psychiatrists and 900 psychiatric nurses serving a population of nearly 30 million people in Ghana.

The low numbers of qualified mental health personnel in Ghana is partly blamed on poor and unsafe working conditions coupled with other de-motivating factors such as: lack of resources at the hospital; a rigid supervisory hierarchy; lack of positive or negative feedback on work performance, and limited opportunities for career advancement within mental health.

Even though previous research endeavors have explored on immensely on workplace demotivating factors, in the three psychiatric hospitals in Ghana, the attention has often been limited in scope. Many of these previous studies concentrated on increment in monthly salaries, early promotion, creating opportunities for further studies and career development.

Albeit these focus areas are important, and remain relevant, occupational health and safety of health workers in these work environments is yet to receive the needed attention from researchers, health managers and policy makers. Safety in healthcare facilities is usually skewed towards patients with little efforts towards ensuring staff safety.

As part of efforts towards improving health and safety conditions in psychiatric hospitals in particular, the Mental Health Authority (MHA) act (Act 846, 2012) [18] was passed albeit its full implementation remains a challenge. The MHA act is currently not backed by a Legislative Instrument (LI) to compel the required government budgetary allocation in the planning and delivery of mental health services in Ghana.

This paper sought to explore experiences of nurses working in psychiatric hospitals on OHS in Accra and Pantang psychiatric hospitals. Key research objectives include ascertaining the knowledge and awareness of nurses on OHS; determining the types of occupational health hazards, and how they are reported by the health workers and the determinants of staff exposure to occupational health hazards.

Methods

Research design

The study is a cross-sectional study among nurses and nurse-aides in two out of the three psychiatric hospitals in Ghana. This design was considered because it promotes attainment of larger sample size and generalizability to study populations. The design also enables the researchers describe and examine associations between key variables of interest [19].

One of the key variables of interest in the study design was the frequency of exposure to occupational hazards where respondents were asked to give arbitrary number times within the day that they experienced occupational health hazards. Beyond the daily average exposure, respondents were asked report on frequency of exposure within a year. Due to potential recall bias, these responses were analyzed on daily and yearly averages because many respondents could not give exact number of times of exposure especially among staff who did not consider some occurrences at the workplace as occupational health hazards.

Study population

There are only three psychiatric hospitals in Ghana serving a population of over 29 million people. This study was conducted in two out of the three psychiatric hospitals. The two selected hospitals were Accra and Pantang psychiatric hospitals both located in the Greater Accra Region (GAR) of Ghana. The third psychiatric hospital (Ankaful Psychiatric Hospital) is in the Central Region.

Accra Psychiatric Hospital (APH) is a specialized health facility that is responsible for the welfare, training, rehabilitation and treatment of the mentally ill [20]. As at the time of conducting this study in March, 2010, APH had a bed capacity of six hundred (600) patients at any given time with a daily in-patient population averaging between 1,100 and 1,300 [21].

There are 21 wards in the APH excluding the Out Patients Department (OPD). The total population of nurses and nurseassistants (also called nurse-aides) then was 354. Professional nurses were 192 and nurses-assistants were 162 [21].

Pantang Psychiatric Hospital (PPH) on the other hand was established in 1975 and it is the youngest among the three psychiatric hospitals. It is located in the Ga East District of the GAR. PPH is also a specialized referral hospital that is responsible for treating mentally ill patients. The hospital has a nurses’ training school that trains psychiatric nurses and also gives training to nursing and medical students on psychiatry affiliation. The bed capacity is 200 but the inpatient population as at the time of conducting this study was 372 patients with a daily OPD attendance of approximately 73 patients [22].

The population of professional nurses in PPH as at February, 2010 was 198 and the nurse-assistants were 95, making a total of 293. These health care personnel work in ten different wards: seven (7) wards for male patients and three (3) wards for female patients and the OPD [22]. Staff to patient ratio per work shift could be sufficiently estimated because staff duty rosters were prepared on monthly basis and due to limited staff numbers, staff was frequently re-assigned to wards and work shifts where their services were most needed. This trend created a fluid situation difficult monitor consistent staff to patient ratio in a particular ward for the various work shifts.

Sampling procedure

The two psychiatric hospitals were purposively selected because they are currently the only healthcare facilities dedicated to psychiatric care in the GAR. At the respondents’ level, proportional stratified random sampling technique was used. The aim was to promote equal representation of the various categories of nurses working in the sampled psychiatric hospitals. The stratified random sampling involved creating two main strata, namely, professional nurses and nurseassistants in the two hospitals.

Quota system was further employed to allocate 60% of the study sample to professional nurses and the remaining 40% to nurseassistants since the population of professional nurses was larger than the nurse-assistants in the two hospitals. Triangulation of the various sampling methods was meant to reduce bias and promote representativeness of the study sample. Individual respondents within the proportioned strata were subsequently sampled by simple random sampling.

For the purposes of this study, the term “nurses” incudes professional nurses (psychiatric and non-psychiatric nurses) and nurse-assistants working in the two psychiatric hospitals. The nurseassistants include Health Extension Workers (HEW), Ward Orderlies (WO), Health Aids (HAs), Nurse Assistants Clinical (NAC) and Nurse Assistants Preventative (NAP). Nurses on post retirement contract and student nurses were excluded from the study because the focus was on experiences of full time staff on workplace safety and occupational health hazards.

Identification and sampling of study subjects

Individual respondents were identified through simple random sampling where, the complete list of nursing staff meeting the eligibility criteria from the two hospitals was retrieved from administrative records. Subsequently, this list was anonymized by assigning codes to these staff. Next, the anonymized individual lists of staff was placed in two separate baskets (each representing the two hospitals) and then each piece of paper picked at random by different research assistants in turns until the desired sample size was reached.

The randomly picked codes of staff were then used to contact the individual staff by the researchers to participate in the study. Staff who did not express interest in participating were replaced through the same random sampling technique. To promote privacy and confidentiality of staff, hospital managers and superiors were blinded to the list of staff finally selected to participate in the study.

Sample size determination

Sample size for the two purposively selected facilities was based on the Krejcie and Morgan statistical tool for determining sample size. This statistical tool gives the recommended sample size for a finite population at the 95% level of confidence.

Krejcie and Morgan [23] stated that with a population size of 650, for example, the representative sample size should be at least 242 and since the population size for the two selected hospitals was 647, a sample size of 350 for both hospitals was deemed representative and generalizable to the whole population. The quota system sampling was used to allocate 60% (210) of the total sample size (n=350) to APH and the remaining 40% (140) allocated to PPH.

Data collection instrument

Process of tool development: The instrument used in the study was mainly structured questionnaires. The questionnaire was developed following a rigorous review of relevant literature on safety in healthcare institutions. Recurrent themes were later synthesized to inform content of the questionnaire. Moreover, exploratory individual interviews were conducted among nurses and nurse-assistants. Responses from these interviews revealed critical topic areas for development of the questions using the inductive approach.

Items included in the data collection tool: The data collection tool was structured in eight (8) sections, namely: demographic data, respondent’s work history, knowledge of occupational health and safety, experience of occupational health hazards, responsibility for work related health hazards, reporting of occupational health hazards, perceptions on safety conditions and suggestions for improving safety of health workers. Questions on perception of safety conditions of the psychiatric hospitals were structured in a Likert scale while the rest of the sections were close and open ended questions. The five point Likert scale was designed as follows: 1= “very bad”, 2= “bad”, 3= “average”, 4= “good” and 5= “very good”. On a whole, the questionnaire had 31 content questions excluding questions on demographic characteristics and work history.

Exploration of administrative records: Besides the interviews with staff, existing administrative records in the two sampled facilities were explored. This approach was meant to independently ascertain the number of documented cases of exposure to occupational health hazards. Also, at the time of conducting this study there were not many available scientific publications on the topic area, particularly in the context of psychiatric hospitals.

In view of this, there was the need to complement the questionnaires administration with review of existing hospital archival records on incidence of exposure to occupational health hazards. Incidence registers were reviewed in eight (8) out of the twenty one (21) wards in Accra psychiatric hospital and eight (8) out of the nine (9) wards in Pantang psychiatric hospital throughout the period of the data collection.

Reliability and internal validity of data collection tool: To ensure internal validity, all questions were informed by the research objectives and the reviewed literature. Moreover, Cronbach’s alpha (α) was conducted to check for scale reliability of all the 32 five-point Likert scale items on perceived workplace safety factors. The Cronbach’s alpha (α) test was found to be above the 0.70 rule of thumb. Piloting of the data collection tool also offered the researchers the opportunity to improve the quality of the questions and thus promote its reliability and internal validity.

External validity and generalizability of the study: Involvement of the different cadres of nursing staff from the two psychiatric hospitals was meant to promote external validity of the study findings. Furthermore, sampling the two largest psychiatric hospitals in Ghana guarantees external validity and generalizability of the findings because over 80% of nursing staff working in psychiatric hospitals in Ghana have been covered. In light of this, it is most likely that views expressed in this study largely represent the general perceptions of healthcare personnel in psychiatric hospitals in Ghana.

Data collection schedule and mode

The schedule of data collection started with permission and administrative approval from the selected health facilities for the study. This was done a week prior to the commencement of the data collection. Afterwards, questionnaires were administered to sampled respondents of the two hospitals after obtaining verbal consent from all staff who volunteered to participate. Since, all the respondents were literates, the questionnaires were largely self-administered by staff who could not immediately spend time with research assistants to respond to the questions. Completed questionnaires were later retrieved by the research assistants for cleaning, coding and data entry.

Piloting: Piloting was done with ten questionnaires in two district hospitals in the GAR. The pretesting was meant to check for consistency, relevance and comprehensiveness of the questions. The pretest responses were desirable and content change was not needed. However, few typographical errors were identified and corrected.

Role of research assistants: The questionnaires distribution was done with the assistance of two trained research assistants. The research assistants’ role included visiting the two psychiatric hospitals and administering to respondents who met the inclusion criteria for the study, using the piloted structured questionnaires. Administration of questionnaires was done simultaneously in the two hospitals to avoid sensitization of respondents who will be contacted in the other hospital later. The questionnaire administration took approximately fourteen (14) days, including mob-up days for staff who could not be interviewed on the day of first visit.

Operational definition of terms: To avoid ambiguity in interpretation of the terms by research assistants to respondents, operational definitions were clearly stated to accompany administration of structured questionnaires. Operational definition of term are explained in the endnote.

Data analysis

The data collected from the institutional surveys was analyzed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.0. Relevant frequency distribution tables were generated for the type of occupational health hazards experienced by the frontline health workers. Multivariate Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression analysis was performed to determine the associations between individual characteristics and work schedules of health staff and their frequency of exposure to occupational health hazards. Prior to the regression analysis, multi-collinearity diagnosis was conducted for all the independent variables of interest and none had a Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) up to 10.0, required for inclusion in the regression model.

The first dependent variable was “Exposure to occupational health hazards”, a binary variable dichotomized into 0= “No” and 1= “Yes” while the second dependent variable was “Frequency of exposure” which is a continuous variable in terms of number of times of exposure to occupational health hazards on daily basis.

The explanatory/independent variables of interest were: professional category (Professional Nurse or Other category of staff), and Work Schedules of staff (Day shift, Day and night shift, Night shift only). Other variables controlled for in the regression model were: staff age, gender (male or female) and number of years of work experience.

Moreover, all five-point Likert scale items were dichotomized into two outcomes by combining “very bad” and “bad” into “Bad”. “Very good” and “good” were combined into “Good”. Test for significance was set at 95% confidence level, thus p-values less than 0.05 were deemed statistically significant.

After the entry and cleaning, all personal staff data were coded and anonymized to promote privacy and confidentiality of the respondents. Staff names were never used throughout the data collection and analysis. Furthermore, staff was assured their responses will not be communicated under any circumstance to the hospital management without their prior notice and permission. Staff was also assured their responses will not be shared with any third party, including their employer with their prior approval.

Results

Demographic data and work history of respondents

Two hundred and ten (210) questionnaires were administered in the APH and 164 of them were retrieved with complete data, representing a return rate of 78%. However, the return rate at the PPH was 96% out of 140 administered questionnaires. The total valid responses from the two hospitals were thus, 296. The field data showed that females dominated in both hospitals, representing 65%. Professional nurses also dominated, representing 60% while nurse-assistants constituted 39% (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Statistic | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Frequency | Percentage%** |

| Male | 105 | 35 |

| Female | 191 | 65 |

| Age | ||

| ≤ 30 years | 170 | 57 |

| 31-60 years | 64 | 22 |

| Missing Data+ | 62 | 21 |

| Professional Category | ||

| Professional Nurses | 179 | 60 |

| Nurse-Assistants | 115 | 39 |

| Missing Data+ | 2 | 1 |

| Work Schedules | ||

| Run Day And Night Shifts | 145 | 49 |

| Permanent Day Shift | 142 | 48 |

| Permanent Night Shift | 3 | 1 |

| Missing Data+ | 6 | 2 |

| Work Experience | ||

| More Experienced 1 | 148 | 50 |

| Less Experienced 2 | 145 | 49 |

| Missing Data+ | 3 | 1 |

| APH (Accra Psychiatric Hospital); PPH (Pantang Psychiatric Hospital); n (sample size) | ||

| )Modeled in this study to mean workers who worked for two years or more | ||

| 2) Modeled in this study to mean Workers who worked for one year or less | ||

| **All percentages have been rounded up to the nearest decimal point | ||

| +Number of respondents who did not answer those questions | ||

Table 1: Demographic and professional characteristics of respondents in APH and PPH (n=296).

On the work schedules of respondents, it was found that staff who alternated between day and night work shifts dominated (nearly 50%); few of the staff indicated they run permanent night shifts; approximately 50% of the staff worked for two years or more and 49% worked for one year or less.

Staff awareness and experiences of occupational health hazards

Out of the 296 valid responses from the two hospitals, it was found that 87% of them said they are aware of occupational health hazards at their workplaces and that working in a psychiatric hospital was more risky than other healthcare facilities.

They further indicated that this risk is largely because Accra and Pantang psychiatric hospitals are major referral facilities for mental health conditions in Ghana.

The overwhelming inpatient and outpatient attendance against poor staff strength, in the opinion of staff, posed significant challenge coupled with overcrowding which has dire consequences on occupational health and safety of personnel in the two hospitals.

Moreover, it was observed that 265 staff (nearly 90%) said they have ever experienced one form of OHH or the other.

The predominant category of OHH experienced by health workers was physical health hazards (53%) followed by biological (20%) and psychosocial (17%) health hazards.

Specific physical hazards experienced included physical assault and battery by clients at the acute stage of their mental health condition.

Emotional events verbal abuse, work related stress, superior relations with subordinates were mentioned by respondents as major psychosocial health hazards often experienced at the workplace. Additionally, exposures to viral, bacterial or fungal infections were the predominant biological hazards reported due to exposure to body fluids of clients.

The pre-dominant reasons cited by victims of these exposures were overcrowding and workload.

Out of the 265 respondents who ever experienced an OHH, 22% said they had at least one exposure a day and 26% had five times exposure or more; 35% could not remember the number of times of exposure; perhaps this group of respondents experienced less than one episode in a day.

Quite a number of the participants got information on OHHs from formal sources such as seminars/workshops (30%) and pre-service education lectures (25%). Other information sources mentioned by the staff were: co-workers, mass media and friends (Table 2).

| Variables | Statistic | |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage%** | |

| Awareness of OHH | ||

| Yes | 258 | 87 |

| No | 35 | 12 |

| Missing Data+ | 3 | 1 |

| Source of Knowledge on OHH | ||

| Seminars/Workshop | 90 | 30 |

| Friends | 13 | 4 |

| Media | 35 | 12 |

| School Lectures | 74 | 25 |

| Co-workers | 17 | 6 |

| Other | 17 | 6 |

| Missing Data+ | 50 | 17 |

| Occupational Hazards Experienced | ||

| Biological Health Hazards | 60 | 20 |

| Physical Health Hazards | 156 | 53 |

| Psychosocial Health Hazards | 49 | 17 |

| Missing Data+ | 31 | 10 |

| Frequency of Exposure Hazards | ||

| Once a Day | 65 | 22 |

| Five Times a Day | 14 | 5 |

| More than Five Times a Day | 36 | 12 |

| More than Ten Times a Day | 27 | 9 |

| Cannot Remember | 104 | 35 |

| Missing Data+ | 50 | 17 |

| APH (Accra Psychiatric Hospital); PPH (Pantang Psychiatric Hospital); OHH (Occupational Health Hazard); n (sample size) | ||

| **All percentages have been rounded up to the nearest decimal point | ||

| +Number of respondents who did not answer those questions | ||

Table 2: Responses on awareness of occupational health and safety in APH and PPH (n=296).

Reporting of OHHs to hospital management

Out of 265 staff who have ever experienced one form of OHH or the other, 153 (52%) of them said they reported their exposure to hospital management.

The reported cases of OHHs included physical injury; bite by patient; needle stick pricks; verbal abuse and sexual harassment (including attempted rape which is a crime in which rape was the motive for an assault, although no rape was carried out).

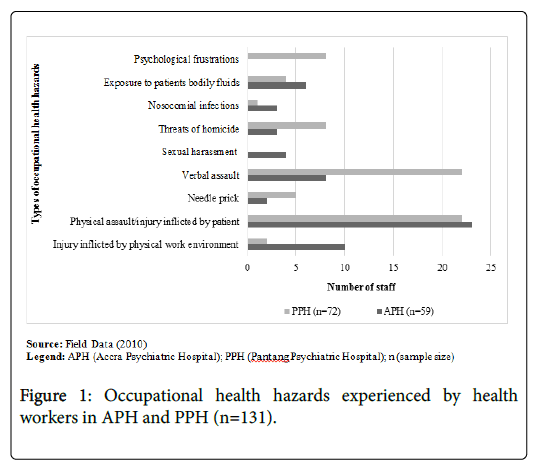

Other reported cases were physical assault by patients; nosocomial infections (also called hospital acquired infections) due to poor sanitary conditions in the ward; threats of homicide and tearing of uniform by patient; contact with body fluids of HIV/AIDS positive patient in the ward (Figure 1).

Seven major forms of occupational health hazards were reported and Table 3 presents the list of these health hazards in a descending order of most reported to least reported.

| Reported Cases | Ranked Order on List |

|---|---|

| Physical attacks by patients+ | 1 |

| Needles tick pricks | 2 |

| Electrical faults and non-functional equipment | 3 |

| Emotional frustrations/burnout | 4 |

| Working without protective gloves | 5 |

| Verbal abuse | 6 |

| Chicken post contracted patients | 7 |

| Physical attacks include: head injuries and contusions from falls, strangulation of staff by aggressive patients, slaps on staff by patients, biting of staff by patient, joint dislocations due to falls on the job. | |

Table 3: Frequently reported occupational health hazards: Presented in a descending order of most.

Follow-up questions were asked on why health workers refused to report exposure to OHHs and the responses included: “problem was dealt with by myself ”, “no channel to report work related health hazard”, “problem perceived as a minor problem”, “no measures would be taken”, “fear of reprimand by superiors”, “forgetfulness”, “no risk allowance paid”, “poor management of reported OHHs”, “blames from management for personal negligence at work”.

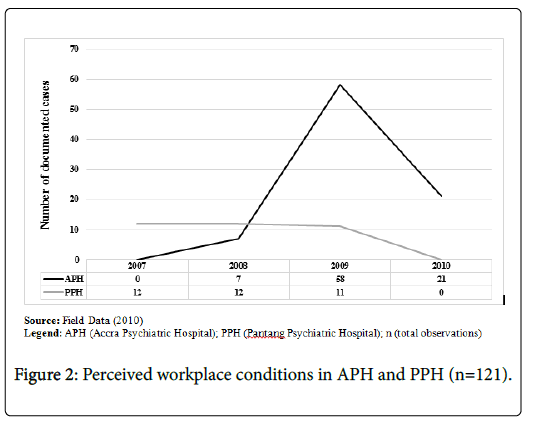

Findings on Ohhs from hospital administrative records: It was found that the total number of documented cases of OHHs over a three year period (2008-2010) in APH was 86 cases while in PPH, 35 cases were documented between 2007 - 2009. Overall, the highest number of documented cases was in 2009 (69 cases) followed by 21 cases in 2010. In 2008, 19 cases were documented in both hospitals while the least documented cases were in 2007 (Figure 2). Interviews with hospital managers revealed that the figures don’t necessarily reflect the actual episodes of staff exposure to OHHs but largely due to inconsistencies and irregular documentation of these episodes, suggesting these figures might be underestimations.

Perception of respondents on safety conditions in their hospitals

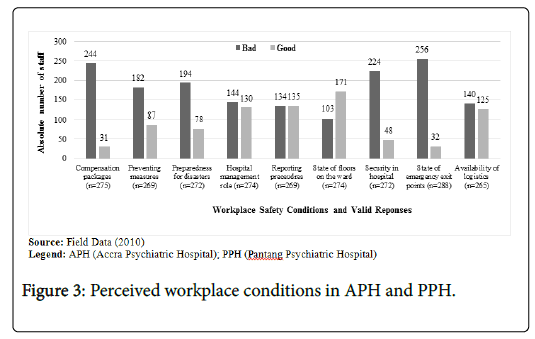

Out of the 265 valid responses on availability of logistics and material resources in the two hospitals, 53% rated that parameter as poor and the remaining 47% said it was bad. On the state of emergency exit points on the wards, 87% rated this safety condition as “bad” and the remaining 13% rated it as: “good”. The security measures for workers of the two hospitals was rated by 224(82%) respondents as “bad” and only 48(18%) staff said it was “good”. Likewise, compensation packages for victims of OHHs; availability of preventive measures and preparedness for disasters were rated by over 60% of the respondents as “bad”. Fifty percent (50%) of the staff indicated that the reporting procedures for exposure to OHHs in their hospitals were “bad” and the remaining 50% said it was “good”. The state of the hospital ward floors was described by 62% of the staff as “good” (Figure 3).

Determinants of exposure to occupational health hazards at the workplace

A multivariate regression test was conducted to determine the factors associated with staff exposure to occupational health hazards. The dependent variables fitted in the regression model were “Exposure to occupational health hazards” (reported as a dichotomous variable, 0= “No” and 1= “Yes”) and “Frequency of exposure to occupational health hazards on daily basis” (reported as a count variable, number of times of exposure daily). The independent variables were: age of staff, gender, and years of work experience, work schedule and professional category (i.e. Nurse or Non-nurse).

It was found that age negatively correlates with the likelihood of a staff experiencing an occupational health hazard. Thus, increasing age of staff reduced the chance of a staff experiencing OHHs (Coef.=-0.16, p=0.012). The frequency of exposure to OHHs on daily basis had no significant association with the age of the staff. It was further observed that male staff were at high risk of experiencing OHHs (Coef.=0.15, p=0.052) than female staff; frequency of exposure to OHHs was observed to be less among professional nurses than non-professional nurses (Coef.=-3.05, p=0.099).

In terms of work duty schedule and exposure to OHHs, staff who worked on day duty schedule only (Coef.=4.49, p=0.011), or alternating day and night schedules (Coef.=4.83, p=0.010) had frequency of experiencing OHHs than staff who worked mainly on night duty schedule. Counter intuitively, increasing years of work experience was found to rather increase a staff’s chance of exposure to OHHs (Coef.=0.07, p=0.002) than those who relatively worked for less number of years (Table 4).

| Dependent variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | Exposure to OHH | p-value | Frequency of Exposure (Daily) | p-value* |

| Coef.++ [(95% CI] | Coef. ++ [(95% CI] | |||

| Age | -0.16 [-0.28 -0.03] | 0.012* | -0.43 [-1.24 0.39] | 0.301 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 0.15 [-0.00 0.30] | 0.052* | s | 0.124 |

| Female | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Profession | ||||

| Professional Nurse | -0.01 [-0.26 0.23] | 0.912 | -1.39 [-3.05 0.27] | 0.099** |

| Other | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Work Schedule | ||||

| Day Only | 0.22 [-0.29 0.73] | 0.4 | 4.49 [1.05 7.93] | 0.011* |

| Day And Night | 0.28 [-0.26 0.82] | 0.308 | 4.83 [1.20 8.45] | 0.010* |

| Night Only | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Work Experience | 0.07 [0.03 0.11] | 0.002* | 0.15 [-0.13 0.43] | 0.285 |

| APH (Accra Psychiatric Hospital); OHH (Occupational Health Hazard); OHS (Occupational Health and Safety); n (Sample size); CI (Confidence Interval) | ||||

| *Multivariate Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression analysis: p-values are statistically significant at 95% confidence level | ||||

| ** Multivariate Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression analysis: p-values are statistically significant at 90% confidence level | ||||

| ++Correlation coefficients | ||||

Table 4: Determinants of staff exposure to occupational health and safety at the workplace.

Discussion

Empirical studies suggest that psychiatric healthcare facilities are increasingly becoming the most dangerous working environments within the health sector in many countries across the globe [24-28]. Resource poor countries such as Ghana are particularly the worst affected given the limited health infrastructure coupled with low health worker density per population of clients with mental health conditions.

In this study it was observed that, exposure of health workers to OHHs in the two sampled hospitals was high. It was found that professional nurses than nurse-assistants were more exposed to OHHs. This observation confirms findings of previous studies that concluded that professional nurses were more likely to experience work related health hazards than lower level cadre of health workers [24,29]. Reasons for this variability were not statistically ascertained in this study. Nonetheless, the observation could be attributed to the fact that professional nurses are more likely to have longer contact hours with psychiatric patients given their job mandate and hence getting more exposed to OHHs. Future studies should therefore consider investigating the determinants for exposure to OHHs among professional and non-professional nursing personnel in psychiatric health facilities.

Another observation was the differences in exposure to OHHs among the gender groupings. According to the hospital administrative records on reported cases of OHHs, females recorded more exposures to OHHs than males. Previous literature on OHHs in psychiatric hospitals appear to support this observation [30,31]. According to Harnois and Gabriel [32], females were mostly attacked and got exposed to other forms of OHHs because they were seen as “weaker vessels” and also because females dominate in the nursing profession in many healthcare facilities including psychiatric hospitals. Some studies further suggest that female psychiatric nurses are more likely to be deficient in self-defence tactics when attacked by patients hence more vulnerable to physical and psychosocial abuses than their male counterparts [32].

In terms of the category of OHHs reported, physical health hazards were reported most by health workers in both hospitals. This finding is contrary to studies by Carmel and Hunter [33] and Barron and Neuman [34] who concluded that psychosocial health hazards were the commonest occupational health hazards experienced by frontline psychiatric health staff.

Moreover, it was found in this study that biological, psychosocial and chemical health hazards were minimally reported by the health workers in the two psychiatric hospitals in Accra. Albeit psychosocial health hazards were experienced more by health workers than physical health hazards, the former were minimally reported and documented by the hospitals as health hazard because of the misconception that such health hazards were “minor” and did not merit reporting [25,32,35-37].

Perhaps psychosocial health hazards such as insults by patients, spitting on nurses, verbal threats of homicide, unjust reprimand by superiors and other stressful events were glossed over as health hazards. Perhaps the low reporting of psychosocial health hazards might be due to ignorance of these components of OHHs. Future studies may have to specifically focus on health workers’ perception of what constitutes an OHH. The response patterns of health workers and the hospitals’ management were the same on psychosocial health hazards. Thus, the knowledge gap on these components of OHHs perhaps permeates both management and the frontline health staff.

On the precursors of exposure to occupational health hazards, most of the health workers attributed their exposure to OHHs to hospital management’s fault or inefficiency, not their personal negligence. On the part of the hospital managements of the two hospitals, the causes of exposure to OHHs included: inadequate financial support from central government, limited logistics and the ever increasing in-patients and out-patient populations in the hospitals. Central government and the Ministry of Health were predominantly blamed for the increasing incidence of exposure to OHHs.

Another revelation was that the reporting system of work related health hazards in the two hospitals was low compared to studies on developed countries [38-41]. For instance, less than 60% of the respondents in both hospitals said they ever reported a work related health hazard to hospital management. This revelation confirms the argument by Richards [5] that OHHs were minimally reported by healthcare professional in many developing countries. In light of this, there is the need to intensify efforts in institutionalizing guidelines for reporting exposure to occupational hazards in psychiatric hospitals in the country.

It was found that nominally, more females got exposed to occupational health hazards, (perhaps because they constituted nearly 70% of the study sample). However, in terms of chances of being exposed to these occupational health hazards, male staff had a higher chance of exposures and was also more likely to report these exposures to hospital management than females.

Barron and Neuman [42] in a related study argued females are more likely to be silent on occupational health hazards that are perceived to be humiliating for a second person to hear of. OHHs such as sexual harassment, including attempted rape and humiliating insults are less likely to be reported by female nurses than their male counterparts largely due to fear of stigma. Increased education for health workers, particularly female workers could help encourage victims to report episodes of the exposure to OHHs.

Overall, it was found that safety conditions in the two psychiatric hospitals were poor. These perceived poor safety conditions do not only constitute an important disincentive but also potentially affects the quality of healthcare delivery to psychiatric patients. Limited resources and logistics, lack of emergency exit points, and security were particularly emphasized by many respondents as major safety threats to frontline health staff in psychiatric hospitals in Ghana. These findings depict concerns raised in similar previous studies on developing health systems in sub-Saharan Africa [43-46].

Limitations

This study had some limitations. First the researchers would have wished to conduct a census of all the three psychiatric hospitals in Ghana and also possibly sample selected psychiatric units in regional and district hospitals across the country to get a wider understanding on the safety conditions in these health facilities, but this was not realized due to due financial resources such a large scale research design.

In view of this, readers are reminded to interpret conclusions in this paper with caution in respect of peculiar safety challenges in psychiatric units at lower levels of the health system. Future researchers interested in the topic area could consider filling the gap in this current research.

Policy Recommendations

Based on the findings of this study, the following policy recommendations are proposed for the Ministry of Health, Mental Health Authority and other relevant stakeholders in the health industry, especially on mental health:

First, the Mental Health Authority in collaboration with the Ministry should institutionalize formal education (through in-service training workshops) to raise awareness on workplace safety in psychiatric hospitals and other healthcare facilities in general. It was found that a significant proportion of the sampled staff was not well informed on occupational health and safety.

Furthermore, there is the need to focus some attention to nonprofessional nursing category in terms of in-service training since this cadre of workers was found to be more prone to experiencing occupational health hazards than their counterparts the professional nurses. Routine continuous professional development (CPDs) on safety precautions could help equip them to reduce their chances of exposure to occupational health hazards.

Also, in-cooperating occupational health and safety into the mainstream list of professional examinable courses by the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) of Ghana, particularly for trainee psychiatric nurses could help imbibe the culture of occupational health and safety practices in nurses during and after pre-service training.

Finally, there is the compelling need to institute new policy reforms and enforce existing ones on mental healthcare in Ghana. Establishment of the Mental Health Authority Act (846, 2012) is a great step towards prioritising mental healthcare in Ghana, including occupational health safety.

Existing occupational health and safety committees in psychiatric hospitals need to be revamped to help enforce policies on occupational health and safety at the health facility levels. Moreover, the Workmen Compensation Act of 1987 (PNDCL 187) be amended and streamlined to meet the specific needs of the psychiatric hospitals in Ghana.

Conclusions

The work of psychiatric health staff is highly risky and unsafe given the poor health infrastructure situation in these health facilities. The situation is aggravated by the lack of clear reporting system for OHHs, documenting and seeking redress for victims of work related health hazards. Limited knowledge of health staff on what constitutes health hazards also potentially clouds true incidence and prevalence rates of these OHHs, particularly non-physical abuses which are often underestimated and hence under-reported.

In light of this, monthly training and education sessions should be revamped and sustained to adequately inform workers on psychosocial OHHs and their prevention thereof. To help attain this, standardized procedures for reporting work related health hazards should be established and workers educated on these procedures.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Research Ethics Committee of the PPH reviewed and approved this research prior to the field data collection. Moreover, an administrative approval was sought from hospital management of the APH as part of the ethics approval process. These ethical approvals were done at the two study hospitals because at the time of conducting the research it was mandatory to acquire these ethical approvals from the study institutions.

Participants’ consent for participation was by verbal consent after the purpose of the study was explained to respondents. Also, information about the respondent was treated confidential in accordance with the PPH ethics committee’s guidelines for conducting research.

Consent to publish

All authors of this manuscript consent to the publication of the manuscript in your journal.

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials used in this manuscript are available without any restrictions. Also, all relevant data and materials used are presented in the manuscript.

Competing interests

All authors of this manuscript declare they don’t have any competing interests.

Funding

Authors did not receive any form of funding support for this research work and development of the manuscript.

Authors' Contributions

ARK: Conceptualization of the manuscript; data collection; data analysis; manuscript writing.

KAP: Peer review of manuscript and supervision.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the hospital management teams, the medical and paramedical staffs of the Accra and Pantang Psychiatric hospitals. Special appreciation also goes to the medical directors, chairpersons of the ethical committees, the hospital administrators, deputy directors of nursing services, the human resource managers, the nurses and nurse-assistants of the two hospitals. Their immense contributions in attaining the needed data for this study are highly appreciated.

References

- International Council of Nurses (ICN) (2007) Guidelines on coping with violence in the workplace. Geneva.

- International Labour Office (ILO)/International Council of Nurses (ICN)/World Health Organization (WHO)/Public Services International (PSI) (1995). Joint programme on workplace violence in the health sector. Geneva.

- Sadleir B (2006) Environmental and occupational health issues in hospitals, mackay base hospital infection control manual.

- http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/interpersonal/en/WVmanagementvictimspaper.pdf

- Slovenko R (2006) Commentary: Violent attacks in psychiatric and other hospitals. J Psychiatry & L 34:249-268.

- Blando J, Ridenour M, Hartley D, Casteel C (2015) Barriers to effective implementation of programs for the prevention of workplace violence in hospitals. Online J Issues Nurs 20:7.

- WHO/Regional Committee for Africa (2004) Occupational health and safety in the African region: Situation analysis and perspectives. Report of the Regional Director. Brazzaville.

- WHO/Regional Office for Africa (ROA) (2005) Implementation of the resolution of occupational health and safety in the African region, meeting report. Ouida.

- Workmen Compensation Act (PNDCL 187) of 1987. Parliament of Ghana. Retrieved on 2017.

- Collins P, Patel V, Joestl S, March D, Insel T, et al. (2011) Grand challenges in global mental health. Nature 475: 27–30.

- Saxena S, Sharan P, Cumbrera M, Saracento B (2006) WHO mental health atlas 2005: Implications for policy development. World Psychiatry 5: 179–184

- WHO: Department of mental health and substance abuse. Ghana country summary (2007) Geneva, Switzerland.

- Jack H, Canavan M, Ofori-Atta A, Taylor L, Bradley E (2013) Recruitment and retention of mental health workers in Ghana. PLoS ONE 8(2): e57940.

- Abaa AR, Atindanbila S, Mwini-Nyaledzigbor PP, Abepuoring P (2013) The causes of stress and job satisfaction among nurses at ridge and pantang hospitals in Ghana. IJASS 3:762-771.

- Fulton BD, Scheffler RM, Sparkes SP, Auh EY, Vujicic M, et al (2011) Health workforce skill mix and task shifting in low income countries: A review of recent evidence. Human resources for health 9:1.

- Burns RB (2000) Introduction to Research Methods. (4th ed) Frenchs Forest: Longman.

- Ghana Health Service (GHS) (2006) Accra Psychiatric Hospital Annual Report.

- Ghana Health Service (GHS) (2010) Accra Psychiatric Hospital (APH). Administrative Records, 2010 Accra, Ghana.

- Ghana Health Service (GHS) (2010) Pantang Psychiatric Hospital (PPH). Administrative Records, 2010 Accra, Ghana.

- Krejcie RV, Morgan DW (1970) Determining sample size for research activities. Educational and psychological measurement. 30:607-610.

- International Labour Office (ILO)/International Council of Nurses (ICN)/World Health Organization (WHO)/Public Services International (PSI) (2002). Joint programme on workplace violence in the health sector, framework guidelines for addressing workplace violence in the health sector. Geneva.

- Di Martino V (2002) Workplace violence in the health sector – Country case studies Brazil, Bulgaria, Lebanon, Portugal, South Africa, Thailand, plus an additional Australian study. Synthesis Report. Geneva: ILO/ICN/WHO/PSI Joint Programme on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector, forthcoming working paper.

- Cooper C, Swanson N (2002) Workplace violence in the health sector: State of the art. Geneva: ILO/ICN/WHO/PSI Joint programme on workplace violence in the health sector.

- Sanati A (2009) Summary of Ghana out of programme experience (OOPE), Royal college of psychiatrists.

- McPhaul K, Lipscomb J (2004) Workplace violence in health Care: Recognized but not regulated. Online J Issues Nurs 1;9.

- Mayhew C, Chappell D (2001) Occupational violence: Types, reporting patterns and variations between health sectors.

- Gyekye SA, Salminen S (2004) Causal attributions of Ghanaian industrial workers for accident occurrence. J Appl Soc Psychol 34:2324-2340.

- Gyekye SA, Salminen S (2006) Making sense of industrial accidents: The role of job satisfaction. J Soc Sci 2:127-134.

- Harnois G, Gabriel P, WHO (2000) Mental health and work: Impact, issues and good practices.

- Carmel H, Hunter M (1990) Compliance with training in managing assaultive behavior and injuries from inpatient violence. Hosp Community Psychiatr 41(5).

- Barron R A, Neuman JH (1998) Workplace aggression-The iceberg beneath the tip of workplace violence: Evidence on its forms, frequency, and targets. PAQ 21:446-464.

- Gunningham N (1999) Integrating management systems and occupational health and safety regulation. J Law Soc 26:191-216.

- Deeb M (2004) Workplace violence in the health sector – Lebanon country case study. Geneva: ILO/ICN/WHO/PSI Joint Programme on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector, forthcoming working paper.

- Makin AM, Winder C (2008) A new conceptual framework to improve the application of occupational health and safety management systems. Safety Science 46:935-948.

- Adei D, Kunfaa E (2007) Occupational health and safety policy in the operations of the wood processing industry in Kumasi, Ghana. JST 27:167-173.

- Ali H, Azimah Chew AN, Subramaniam C (2009) Management practice in safety culture and its influence on workplace injury: An industrial study in Malaysia. Disaster Prev. Manage 18:470-477.

- Antoniou SG, Davidson MJ, Cooper CL (2003) Occupational stress, job satisfaction and health state in male and female junior hospital doctors in Greece. J Manag Psychol 18:592-621.

- Barron RA, Neuman JH (1996) Workplace violence and workplace aggression: Evidence on their relative frequency and potential causes. Aggressive Behav 22:161-173.

- International Labour Organization (ILO) (2003) Workplace Violence in the Health Services. Geneva, Fact Sheet.

- International Labour Organization (ILO) (2003). Code of practice on workplace violence in services sectors and measures to combat this phenomenon. Geneva.

- Code of practice on workplace violence in services sectors and measures to combat this phenomenon

Citation: Alhassan RK, Poku KA (2018) Experiences of Frontline Nursing Staff on Workplace Safety and Occupational Health Hazards in Two Psychiatric Hospitals in Ghana. Occup Med Health Aff 6:274. DOI: 10.4172/2329-6879.1000274

Copyright: © 2018 Alhassan RK, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 6413

- [From(publication date): 0-2018 - Sep 23, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 5427

- PDF downloads: 986