Research Article Open Access

Evidence-Base Unani Medicine: Need of Appropriate Research Methods

Malik Itrat* and Saba Khan

Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, National Institute of Unani Medicine, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

- *Corresponding Author:

- Malik Itrat

Department of Preventive and Social Medicine

National Institute of Unani Medicine, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

E-mail: malik.itrat@gmail.com

Received date: November 04, 2016; Accepted date: November 10, 2016; Published date: November 14, 2016

Citation: Itrat M, Khan S (2016) Evidence-Base Unani Medicine: Need of Appropriate Research Methods. J Tradi Med Clin Natur 5:197.

Copyright: © 2016 Itrat M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Traditional Medicine & Clinical Naturopathy

Abstract

Every health care system must be evidence based and Unani system of medicine ought to be no exception. An evidence base is needed at every level of health-care, right from diagnostics to the therapeutic decision making. Unani medicine requires thorough work to bring out evidence basis not only to support its interventions but also to its fundamental concepts to create scientific and logical basis on which therapeutic decisions are made. However, when pleading for evidence, problems associated with the nature of evidence and their relevance to Unani system of medicine ought to be thoroughly debated. Though Unani system and biomedicine share the same spirit of open and sincere scientific enquiry, their fundamentals, epistemology, logic and theories are distinct. Unani medicine is basically holistic, whereas biomedicine is reductionist. These epistemic variations call for the use of appropriate and acceptable research methods by involving experts from Unani system and biomedicine. The classical approach of this system should not be compromised for the convenience of prevailing research strategies. Various research strategies like reverse pharmacology to unravel the mechanism of action of drugs, pharmaco-epidemiology to study the toxicity of herbo-mineral preparations, retrospective treatment outcome surveys as a starting line to study the efficacy of drugs and whole system research to evaluate the efficacy of packaged interventions have been proposed by scientists to generate evidence in traditional medicine, that are also applicable to Unani system of medicine. In this paper research methods, which are appropriate to generate scientific evidence in Unani medicine are discussed.

Keywords

Unani medicine; Evidence-based medicine; Research methods

Introduction

The practice of Unani system of medicine stretches all the way back in to the misty dawn of time. The Asia-Pacific database on Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) by Asia-Pacific Cultural Centre for UNESCO (ACCU) has deemed Unani System of Medicine as one of the oldest and most acceptable systems of medicine. It is practiced in India and all over the world particularly in Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Iran and most parts of South East Asia [1]. The Unani system of medicine as its name suggests has its origin in Greece. The core philosophy of this system was conceptualized by Hippocrates. After him, Arab and Persian scholars made great contributions and hold a large share in what constitutes the Unani literature today. It was introduced in India by the Mughals and since then has enjoyed popularity amongst the masses and now forms an integral part of the healthcare delivery system of the country.

The strength of the system is in its holistic and individualistic approach to health promotion, disease prevention and treatment. It offers an effective treatment for various gastrointestinal, respiratory, genitor-urinary, musculoskeletal, neurological, cardiovascular, lifestyle and metabolic disorders [2]. Although the government has given great importance to the multi-faceted development of this system of medicine to make full use of its potential in the Indian healthcare delivery, the Unani system of medicine has not gained much recognition within the times.

A number of issues have been at the back drop of this lag, primary of which has been the lack of quality data on safety and efficacy of Unani drugs required to put the system’s practices at par with contemporary medical systems. The main reason behind this inadequacy of research data is the lack of appropriate and accepted research methods that can be used for evaluating the system’s practice. However the question, whether an evidence base is required for a system which has been in widespread practice for ages, has puzzled many a mind. This question needs to be analyzed in terms of extended benefits of putting an evidence basis for practice of Unani medicine, primarily for providing a prospectively better and dependable health care and secondarily for growth of Unani medicine as a contemporary science. Unani System of medicine indeed needs intensive work to bring out an evidence basis to its nosology, primarily to support its concepts and to make a sound scientific basis for its therapeutic interventions. Additionally, it also needs evidences to support its interventions in varied clinical conditions to the extent that their application in a given condition is justified.

The seemingly obvious task of deciphering and devising methods of furnishing this evidence leads us to a new set of questions. How can Unani drugs be standardized using parameters of another health system? Should all formulations used in the system be re-evaluated using biomedical parameters and would this process be affordable? While it is important to substantiate an evidence base for Unani medicine, it is equally important to ensure that the epistemological differences between the two systems are taken into account when developing research protocols.

The guiding dictum should be to identify such tools and methods for research in Unani medicine which are sensitive enough to respect the desired rigor of science as well as the original holistic nature of Unani medicine equally.

Unani Medicine: The Amendments Needed

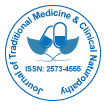

In the context of recognition and resurgence of Unani system of medicine globally, there are certain issues that need to be critically understood and examined. In our opinion, Unani medicine requires extensive research in the following areas:

• Revalidation of Unani fundamentals so that they can be inexplicably stated and understood.

• To find out better treatment modalities for existing diseases and for newer diseases.

• To standardize the treatment procedures scientifically.

• To establish dose, duration, indication and side-effect profile of drugs.

• Unani and modern drugs interactions (Figure 1).

Applying Evidence Base to Unani medicine: What are the tools?

Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM) is defined as the systemic approach for finding and analyzing published data for the basis of clinical decision making [3]. It is also defined as the integration of the best research evidence with clinical expertise and patient values to make clinical decisions [4]. EBM bridges the gap between modern day research and physician, as current research findings and data are often required to diagnose and treat patients. EBM focuses on research dealing with day to day practice of patient care. The evidence may prove or disprove previously accepted methods or demonstrate new ways of care that are more accurate and effective and less harmful. In biomedicine, the golden standards of EBM are formulated from “Randomised Controlled Trials”.

Although RCT usually considered to be amongst the top in the hierarchy of study designs, it is not the only tool that can be used unequivocally to provide evidence in traditional systems also. The RCT design made for testing a single entity cannot be used for testifying Unani medicine in which the hall mark of treatment itself is packaged intervention. Indeed, an RCT may be inappropriate or inadequate in answering determined questions and/or in certain contexts [5]. What reckons a clinical study to be better evidence is neither its logistics nor the sample size; rather it is the connexion of the research question with its design, the rigor of data collection and analysis along with explicit reportage of the observed effects [6].

Various scholars have explored different models of testing the validity and standardization techniques in traditional medicine. Verhoef and Van der Greef have considered observational studies to be better tools for evaluating the efficacy and safety of traditional medicine as they are cheaper, have higher external validity and accommodate better to the medical epistemology of the Unani system of medicine [7,8].

There are a number of research designs that can substantiate evidence base to the Unani system of medicine. They are: the retrospective treatment – outcome study, the prognosis – outcome study, the dose–escalating prospective study for detecting a dose-response phenomenon in humans, pharmaco-epidemiology - to document the safety of Unani medicines, especially herbo-mineral preparations and reverse pharmacology - to unravel the biological mechanisms behind the drug action.

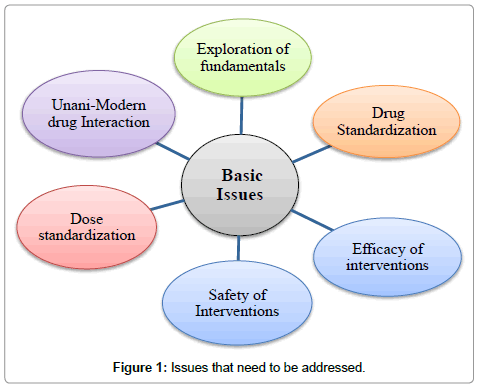

Retrospective Treatment-Outcome (RTO) survey: The collection of clinical data, such as patient status and progress after the use of Unani medicines, can help in the study of the effectiveness and safety of Unani practices and products. These surveys can analyze records of patient’s progress (outcome) along with the different treatments used for a given disease or syndrome. It will make possible to perform correlation tests between treatment and outcome, providing indices of effectiveness and safety. It will also provide data about precautions and contra-indications. RTO surveys are usually conducted with a questionnaire applied to a representative sample of a population. Inclusion criteria are “having suffered from the disease of interest since weeks/months/year”. For a benign health problem, the recall period is kept short (e.g., two weeks) for accuracy and for a severe problem, it can be longer (e.g., 1 year). Patient’s progress under various treatments is recorded, and then analyzed with adjustment for confounding factors. If we find a good association between a given treatment for a health problem and patient cure with no significant side effects, this could mean that the treatment is effective and should be validated further with other methods. Precise data about drug collection, preparation and dosage that are of great importance, in order to facilitate future replication of the study, can also be gathered during the survey (Figure 2 and Table 1). These types of studies can also provide baseline information about known side effects, incompatibilities and limitations (including experience with small children and pregnant women), which can be the precious signs for further research on its toxicity [6,9].

Figure 2: Design of a clinical study eliciting the best clinical outcome among numerous alternative treatments for the same ailment: the Retrospective Treatment-Outcome study. B: Best Outcome; S: Same Outcome; W: Worst Outcome [6].

| • (Last time you used this treatment for which health problem.) • What was the patient progress? (Cured/better/same/worse). • After how many days? • Have you experience any allergy or side effects during this treatment? • Have you used this drug during pregnancy? • Have you taken any precautions during this treatment? • Is there anything that you have not eaten or done at the same time? |

Table 1: Questions to be asked during field work to get basic information on effectiveness and safety of a traditional treatment [10].

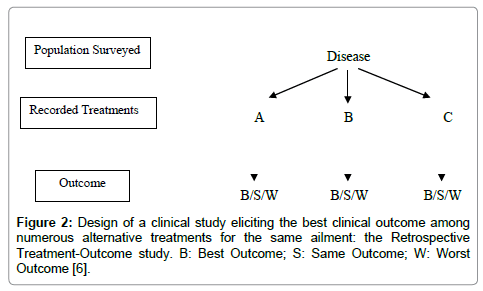

Comparison of Prognosis and Outcome (CPO) study: It is also an observational study which can be useful to assess the overall results of therapeutic interventions of Unani medicine. It explores whether health care dispensed by Unani practitioners is as good as – or better than – what could be expected with allopathic medicine in the area. What could be expected with conventional medicine is an allopathic practitioner’s prognosis which is compared with actual patient progress (clinical outcome) with Unani treatment.

A four-point relative scale allows comparisons between expected and observed patient progress. Analysis of results will show that, whether the outcome with Unani treatment is same, worse or better than standard modern medicine. Those cases, in whom outcome is better than expected, will suggest that Unani medicine has better results than standard modern medicine for those ailments, and it would be advisable to focus further research on such treatments in those diseases (Figure 3) [10,11].

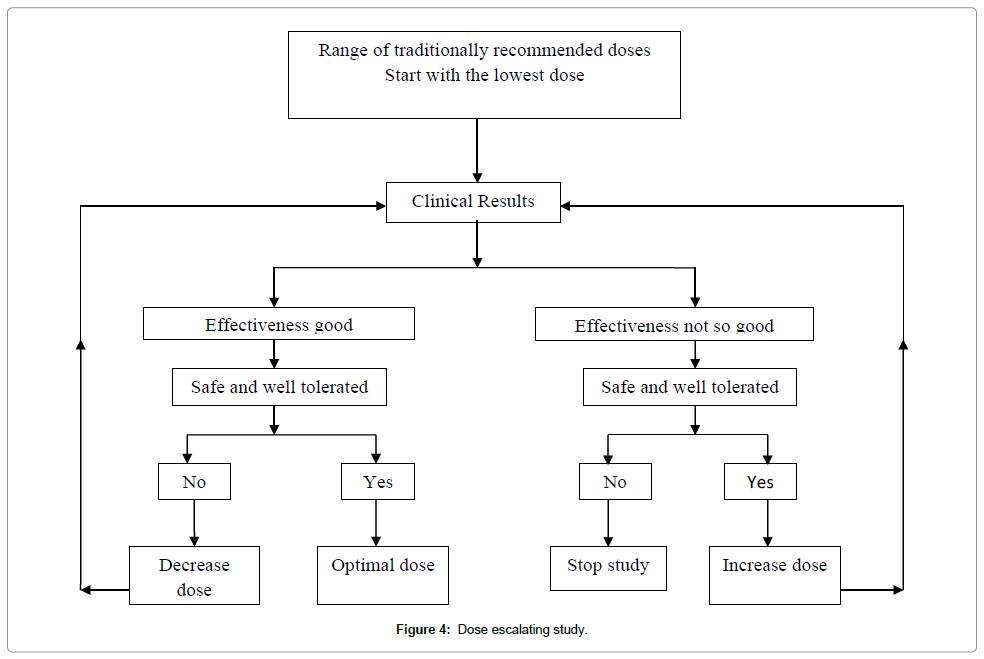

Dose–escalating prospective study: When any drug is given in extremely variable doses and the preliminary observations indicate that the therapeutic range is large and the probability of toxicity at the doses used is very low, a Prospective Dose Escalating (PDE) trial can be organized on a small sample. In this study, patients are allocated into different groups and practitioner gives to one group, what he/she considers the lowest dose, to another group, the middle range dose and upper range dose to a third group. There should be no difference in inclusion criteria between the groups, and patients should be randomly allocated to a particular dosage group. If statistically significant difference appears in outcome between various doses groups, the presence of a dose–response phenomenon can be estimated, indicating specific activity at different doses. In the next step, if all pre-requisites are met, then a prospective randomized controlled trial can be conducted, with some adaptations [6] (Figure 4).

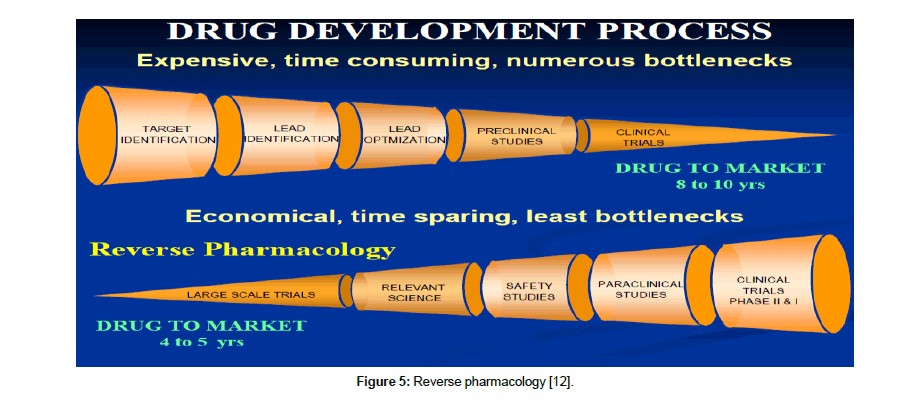

Reverse pharmacology: This research technique offers an effective answer in understanding how Unani drugs work. Reverse pharmacology is defined as the science of integrating documented clinical experiences and experimental observations into leads by interdisciplinary exploratory studies and further developing these into drug candidate or formulations through robust preclinical and clinical research [12]. This approach is especially applicable to traditional treatments, where the safety and efficacy are already known but need validation to support their usage. Such studies helps in revealing underlying mechanisms of drug action and give a better picture of their efficacy, safety thus hugely aiding their acceptability [13].

Reverse pharmacology approach helps in reducing three major bottlenecks: costs, time and toxicity. It comprises of three stages— experiential, exploratory and experimental. In Experiential phase, a number of clinical drug candidates can be shortlisted for going through the next two stages. It includes robust documentation of clinical effects of standardized drugs by meticulous record keeping. The exploratory studies will cover dose-activity in ambulant patients and selected in-vitro and in-vivo models to evaluate the key target. The experimental stage then employs relevant basic and clinical science to study the plant or a molecule at different levels of biological organization especially at the molecular level (Figure 5). This would define the safety, efficacy, preventive or therapeutic dimensions of the new or natural drug [14].

Figure 5: Reverse pharmacology [12].

Pharmaco-epidemiology: As there are questions about efficacy of Unani drugs, there are also questions about the toxicity of its formulations especially herbo-mineral preparations. In this scenario, pharmaco-epidemiological studies can provide valuable information concerning the relationship between therapeutic agents and adverse and beneficial health outcomes. Although Unani formulations are in use since centuries which itself is a proof to their safety but such studies can be used to further hone their usage and acceptability. Pharmaco-epidemiology is the study of drug efficacy, toxicity and patterns of use in large populations. With the help of these studies, we can salvage safety data from pool of patients, who have already used Unani drugs. If Unani preparations are found to be safe, it can advance as major evidence in support of this system [15,16].

Conclusion

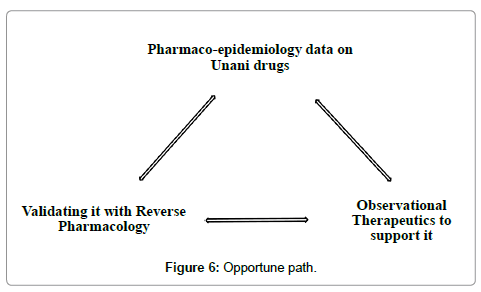

Validation gives credibility to practice. Structured validation is undoubtedly the key to furnish an evidence base to the Unani system of medicine. Current research in Unani Medicine uses modern scientific parameters as the exclusive yardstick. Unani treatment methodology is force fitted into conventional research designs and the knowledge so obtained is used within the framework of biomedicine. Packaged Unani interventions are broken down to their simpler components in an attempt to study the efficacy of these broken components in a specific disease. This leads to trimming and modification of Unani treatment to fit into the conventional research design. Consequently, the results of such ill designed studies are unlikely to add any value to this system. The focus of research has to shift from just the drugs and practices to the concepts that warrant their use. In Unani system of medicine it is not only desirable to re-validate the use of drugs but also the fundamentals on which therapeutic decisions are made. This may require appropriate methodological modifications. Research designs sensitive to the system need to be adapted and if necessary, reinvented. The three pronged strategy of leveraging the benefits of pharmaco-epidemiology, observational therapeutics and reverse pharmacology should be taken up as the primary step in this direction (Figure 6).

References

- Asia-Pacific Database on Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) by Asia-Pacific Cultural Centre for UNESCO (ACCU).

- Husain A, Sofi G, Tajuddin, Dang R, Nilesh Kumar (2010) Unani System of Medicine-Introduction and Challenges. Med J Islamic World Acad Sci 18: 27-30.

- Sacket DL, Rosenburg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS (1996) Evidence-based Medicine: What it is and it isn’t. BMJ 312: 71-72.

- Krishnan R (2013)Comprehending Evidence-Based Ayurveda. Int J Ayur. Pharma Research 1: 1-3.

- Black N (1996)why we need observational studies to evaluate the effectiveness of health care? BMJ 312:1215–1218.

- Graz B, Elisabetsky E, Falquet J (2007) Beyond the myth of expensive clinical study: Assessment of traditional medicines. J Ethnopharmacol. 113: 382–386.

- Verhoef MJ, Lewith G, Ritenbaugh C, Boon H, Fleishman S, et al. (2005) Complementary and alternative medicine whole systems research:Beyond Identification of Inadequacies of the RCT. Complement Ther Med13: 206-212.

- Van der Greef J (2007) Perspective: All Systems Go. Nature 480: S87

- Graz B, Diallo D, Falquet J, Willcox M, Giani S (2005) Screening of traditional herbal medicine: first, do a retrospective study, with correlation between diverse treatments used and reported patient outcome. J Ethnopharmacol 101: 338–339.

- Graz B, Falquet J, Elisabetsky E. (2010) Ethnopharmacology, sustainable development and cooperation: The importance of gathering clinical data during field surveys. J Ethnopharmacol 130: 635–638.

- Graz B, Falquet J, Morency P (2003) Assessment of alternative medicine through a comparison of the expected and observed progress of patients: a feasibility study of the prognosis/follow-up method. J Altern Complement Med9:755–761.

- Anju S, Sumit S, Sujata S (2015)Reverse pharmacology: A new approach to drug development.Innoriginal: Int J Sci Nat2: 7-12.

- Patwardhan B, Vaidya ADB (2010) Natural products drug discovery: accelerating the clinical candidate development using reverse pharmacology approaches. Indian J Exp Biol48: 220–227

- Patwardhan B, Vaidya ADB, Chorghade M, P Joshi Swati (2008) Reverse Pharmacology and Systems Approaches for Drug Discovery and Development. Curr Bioact Compd 4: 1-12.

- Brian L Storm (2000) Pharmacoepidemiology. (3rd ed.). Chicester: John Wiley and Sons Ltd: 3–11.

- Itrat M (2016) Research in Unani Medicine: Challenges and Way Forward. Altern Integr Med 5: 215.

Relevant Topics

- Acupuncture Therapy

- Advances in Naturopathic Treatment

- African Traditional Medicine

- Australian Traditional Medicine

- Chinese Acupuncture

- Chinese Medicine

- Clinical Naturopathic Medicine

- Clinical Naturopathy

- Herbal Medicines

- Holistic Cancer Treatment

- Holistic health

- Holistic Nutrition

- Homeopathic Medicine

- Homeopathic Remedies

- Japanese Traditional Medicine

- Korean Traditional Medicine

- Natural Remedies

- Naturopathic Medicine

- Naturopathic Practioner Communications

- Naturopathy

- Naturopathy Clinic Management

- Traditional Asian Medicine

- Traditional medicine

- Traditional Plant Medicine

- UK naturopathy

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 15916

- [From(publication date):

November-2016 - Nov 21, 2024] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 14839

- PDF downloads : 1077