Evaluation of the Proportion of Cariogenic Bacteria Associated with Dental Caries

Received: 12-Oct-2017 / Accepted Date: 30-Oct-2017 / Published Date: 31-Oct-2017 DOI: 10.4172/2161-1165.1000327

Abstract

Background: Public oral health surveys have shown that the prevalence of dental caries in adults is increasing worldwide, resulting in increased workload and costs of dental and other clinical oral health services.

Total streptococci are broadly grouped into mutans streptococci and three other species. They constitute a majority of bacteria found in the mouth. Of the total streptococci, the group of bacteria that primarily causes dental caries is mutans streptococci, which consists of seven species. Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans) is the mutans streptococcus most strongly associated with dental caries. To date, no simple assay (kit) has been developed for detecting S. mutans using plaque samples for caries risk assessment. This study aimed to evaluate the association between S. mutans and dental caries in adults based on the number and proportion of cariogenic bacteria in toothbrush plaque samples by culture methods to obtain basic data to develop clinical and chairside culture assay for caries risk assessment.

Materials and Methods: Plaque samples from 164 adult volunteers were obtained using sterile toothbrushes. The ratio of S. mutans to total streptococci (Sm/TS ratio) was determined by counting the number of colonies by culture methods. The extent of dental caries and the relative risk based on bacterial counts were assessed.

Results: The differences between Sm/TS ratios (%) in caries-free, medium-caries, and caries-active groups were statistically significant (p<0.001). The difference in the number of decayed, missing, and filled teeth (DMFT) in the four risk groups, each defined by Sm/TS ratio (%), was statistically significant (p<0.01). The risk associated with Sm/TS ratio was more significantly associated with the number of DMFT than with the number of S. mutans, and this parameter was useful in the selection of high-risk dental caries subjects.

Conclusions: The results of the present study suggested a significant association between the levels of S. mutans and dental caries using dental plaque samples in adults and indicate that quantification of Sm/TS ratio is effective for detecting subjects with the severity of dental caries. This approach has the potential for previous study of the development of simple culture assay for a risk assessment that may be incorporated into future clinical or epidemiological studies measures for the improvement of oral health wor ldwide.

Keywords: Dental caries; Plaque samples; Streptococcus mutans; Proportion of cariogenic bacteria; Culture method; High-risk dental caries subjects; Epidemiological study

Introduction

Public oral health surveys have shown that the prevalence of dental caries in adults is increasing worldwide, resulting in increased workload and costs of dental and other clinical oral health services [1-3].

Colonization of the tooth surface with S. mutans, which is both acidogenic and aciduric, is considered to be a major cause of dental caries [2,4,5]. For initiating carious lesions in the enamel, S. mutans forms colonies on the tooth surface, creating an environment that poses a high risk of dental caries [6]. However, much of the existing research on the frequency and distribution of S. mutans and its correlation with dental caries has focused on infants and children [7-23], and there are very few reports concerning adults [24-26].

To practice oral healthcare that focuses on the prevention of oral diseases, it is necessary to provide appropriate health instructions after predicting the risk of morbidity [2,27]. This can be accomplished by methods such as dental caries activity tests that are used to evaluate the risk of dental caries [28-30]. Among these tests, examinations using bacteriological methods are usually assessed on the basis of the quantification of the number of S. mutans. In contrast, some reports [31,32] have utilized bacterial counts to determine the proportion of cariogenic bacteria (S. mutans in total streptococci, S. mutans /total streptococci [Sm/TS] ratio), which in turn helps to assess the risk of dental caries. However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has comparatively evaluated the individual risk of dental caries in a given population based on the quantification of the number of S. mutans and the Sm/TS ratio.

Stimulated saliva samples are commonly used to assess caries activity in the oral cavity because quantitative measurement of such samples is easy [28,30]. However, cariogenic bacteria are primarily present in plaque on the tooth surface, and hence, these bacteria must be counted in the plaque to assess caries activity [27,33]. In addition, a previous study demonstrated that toothbrush plaque samples (plaque suspensions) collected after brushing all the teeth can be quantitatively measured [31], but this study only investigated the validity of using such samples. A parameter must have a confirmed association with the occurrence of dental caries to be a useful evaluation standard for the assessment of caries activity [2,27,28]. To date, no studies have comparatively evaluated the usefulness of toothbrush plaque samples for assessing the risk of dental caries based on the number of S. mutans and Sm/TS ratio.

Obtaining samples from children and elderly individuals with commonly utilized methods (i.e., sample saliva while masticating on chewing gum) is challenging. However, the use of plaque as a specimen is problematic in terms of quantification and reproducibility. In the present study, we used a quantitative plaque analysis method using brushing that easily obtains samples from children and elderly individuals.

Simple culture kits are commercially available and used in clinical or epidemiological studies [2,27,28]. These kits can conveniently detect and evaluate mutans streptococci at the chairside without expensive equipment or facilities, but these use saliva samples and detect only mutans streptococci, which comprises seven types of bacteria. Therefore, such kits cannot be used to evaluate only S. mutans, which are the most critical pathogenic bacteria that causes dental caries.

A previous study reported a monoclonal antibody test using immunochromatography that selectively detects S. mutans [28]. Although a measurement kit using immunochemical methods instead of culture methods was made commercially available, the sale was discontinued because of imprecision and high cost.

This pilot study investigated basic data to develop a clinical and chairside culture assay (kits) with higher precision for a risk assessment using quantitative plaque and Sm/TS ratio analyses of cariogenic bacteria without polymerase chain reaction or immunohistochemical methods. The aim of this study was to evaluate associations between dental caries and levels of Streptococcus mutans in adults based on the Sm/TS ratio and using dental plaque samples harvested from sterile toothbrushes.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and preparation of plaque samples

A cross-sectional study was conducted in an adult population sample at Nihon University School of Dentistry at Matsudo. In total, 164 adult volunteers in good physical condition and oral health and aged 21–27 years were enrolled as experimental subjects. Investigation of caries status and collection of plaque samples were performed at our university. Subjects with any systemic disease, those using medications affecting salivary secretions, and those taking antibiotics were excluded from the study. The selected individuals were instructed not to eat/drink, use a mouth wash, or smoke 3 h prior to their appointment. Subjects were informed about the aim of this study well in advance, and informed consent was obtained from each of them. This study was conducted with the approval of the Ethics Committee of the Nihon University School of Dentistry, Matsudo. Oral samples of brushingplaque were successively collected from each subject by the following methods. A large portion of plaque was scraped off all their teeth by vigorous brushing for 1 min using a sterile toothbrush and was collected into a sterile bottle through a mouth rinse for 30 s with 5 ml phosphate-buffered saline and used as brushing-plaque sample [31].

Bacterial analysis

Mitis Salivarius agar (Difco, Detroit, MI, USA) containing 20% sucrose, 0.25 U bacitracin, and 1% tellurite, supplemented with 20 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L colistin, 10 g/L nalidixic acid, and 4 g/L gramicidin, was used as a selective medium for total streptococci and Mutans streptococci, respectively [34]. Within 3 h of sampling, clinically isolated samples were disrupted by sonication (50 W, 20 s) using ultrasonic apparatus (5202 Type, Otake Works, Tokyo, Japan), serially diluted with chilled brain heart infusion broth, and inoculated on selective media using a spiral plating system (Model-D, Gunze Sangyo, Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

After anaerobic incubation for 48 h, the number of total streptococci and S. mutans colonies on plates were counted.

S. mutans could be visually distinguished on the basis of the morphology of colonies on the agar plates. The ratio of S. mutans to the total streptococci was determined by counting their colonies and designated as Sm/TS ratio [31,32].

Investigation of caries experience and the classification of caries risk groups

Subjects’ caries experience was determined according to WHO standards [35], and the presence of decayed, missing, and filled teeth (DMFT) was calculated and recorded for each subject.

Based on classification (mean ± standard) for DMFT (dental caries), S. mutans counts and the Sm/TS ratio of subjects from the caries-free group (DMFT=0) were compared with those of subjects from the caries-medium and caries-active groups used as controls In addition, risk levels were categorized into four categories from highest to lowest bacterial levels, with bacterial levels as classification standards (in the descending order: risk 4, risk 3, risk 2, and risk 1). The number of DMFT for risk 4 (n=41), risk 3 (n=41), risk 2 (n=41), and risk 1 (n=41) were calculated (intergroup comparison).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics and statistical analyses were performed using statistical software (SPSS 22.0, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Mann– Whitney U test was used for comparison between the two groups. The Bonferroni test was used to perform comparisons among the three study groups and the four risk category groups. A probability (p) value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The detection rate of total streptococci for all subjects (n=164) was 100%. The mean detected bacterial number (107 CFU/mL) of total streptococci was 9.95 ± 12.35 (mean ± SD), and the detection rate of S. mutans was 92.07%. The mean detected bacterial number (105 CFU/mL) of S. mutans was 25.61 ± 85.49. The mean Sm/TS ratio (%) was 2.33 ± 5.03%. The mean number of DMFT for all subjects was 7.59 ± 6.01.

On the basis of the mean number of DMFT (mean number, 7.59), the subjects were classified into caries-free (DMFT=0, n=21), mediumcaries (DMFT=7 and 8, n=18, control group), and caries-active groups (DMFT ≥ 16, n=19, control group). The number of total streptococci in the caries-free, medium-caries, and caries-active groups were 10.78 ± 16.34, 9.54 ± 6.94, and 9.22 ± 10.23, that of S. mutans were 1.64 ± 2.72, 9.21 ± 14.77, and 58.87 ± 131.34, and Sm/TS ratios were 0.32 ± 0.49, 1.31 ± 2.11, and 4.95 ± 3.75, respectively. The intergroup differences were statistically significant (p <0.001) for the Sm/TS ratio (Bonferroni test, Table 1).

| Members of Total Streptococci 10 CFU/ml | Members of S. mutans 10 CFU/ml | Sm/TS ratio % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caries active group | 9.22 ± 10.23 | 58.87 ± 131.34 | 4.95 ± 3.75*** |

| Caries medium group | 9.54 ± 6.94 | 9.21 ± 14.77 | 1.31 ± 2.11*** |

| Caries-free group | 10.78 ± 16.34 | 1.64 ± 2.72 | 1.64 ± 2.72 |

Table 1: Comparison of number of total streptococci, number of S. mutans, and Sm/TS ratio (%) between the control (caries-active and caries-medium) and caries-free groups S. mutans counts and Sm/TS ratios of the subjects in the caries-free group were compared with the bacterial levels in caries-medium and caries-active groups as controls.

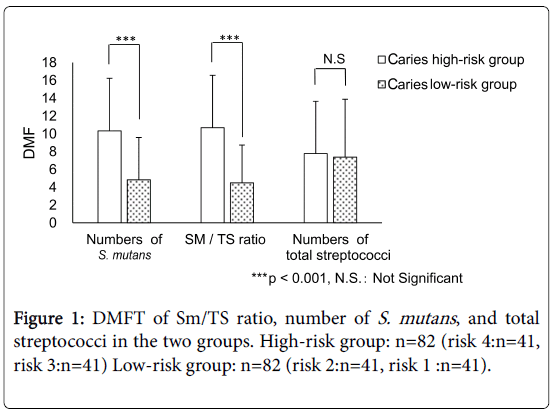

The number of S. mutans (105 CFU/mL) in the four risk groups [risks 4, 3, 2, and 1 (n=41 each)] were 91.60 ± 154.18, 8.83 ± 3.93, 1.79 ± 0.79, and 0.23 ± 0.27, respectively. Moreover, the number of DMFT for the high-risk (risks 3 and 4, n=82) and low-risk (risks 1 and 2, n=82) groups (as defined by the number of S. mutans) were 10.34 ± 5.89 and 4.83 ± 4.76, respectively, demonstrating a significant difference between the groups (p<0.001). The Sm/TS ratios (%) of the four risk groups [risks 4, 3, 2, and 1 (n=41 each)] for caries risk were 7.51% ± 8.08%, 1.37 % ± 0.45%, 0.38% ± 0.18%, and 0.05% ± 0.05%, respectively. The number of DMFT relating to the Sm/TS ratio in the caries high-risk (risk 3 and 4, n = 82) and caries low-risk (risk 1 and 2, n=82) groups were 10.68 ± 4.49 and 5.94 ± 4.24, respectively, demonstrating a significant difference between the groups (p<0.001). The number of total streptococci (107 CFU/mL) in the four risk groups [risks 4, 3, 2, and 1 (n=41 each)] were 25.45 ± 16.17, 8.61 ± 2.18, 4.26 ± 0.82, and 1.50 ± 0.76, respectively. The number of DMFT relating to the number of total streptococci in the high-risk (risk 3 and 4, n=82) and low-risk (risk 1 and 2, n=82) groups were 7.78 ± 5.51 and 7.39 ± 6.49, respectively. However, the differences between the groups were not significant (Mann–Whitney U test, Figure 1).

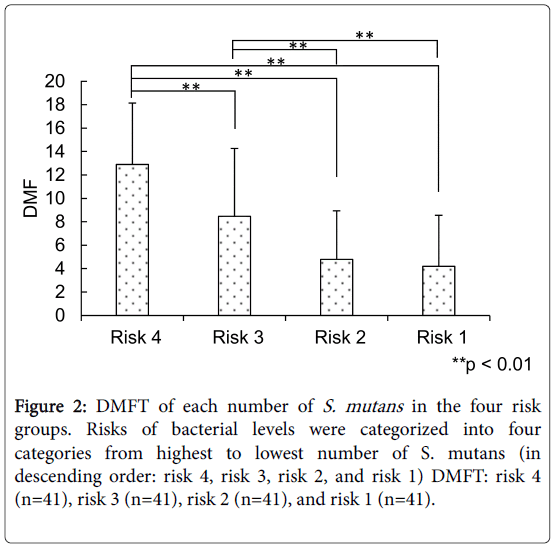

The number of DMFT relating to that of S. mutans in the four risk groups [risks 4, 3, 2, and 1 (n=41 each)] were 11.70 ± 5.79, 8.98 ± 5.73, 6.54 ± 5.17, and 3.12 ± 3.61, respectively, demonstrating significant differences among these classes (p<0.01, Bonferroni test, Figure 2).

Figure 2: DMFT of each number of S. mutans in the four risk groups. Risks of bacterial levels were categorized into four categories from highest to lowest number of S. mutans (in descending order: risk 4, risk 3, risk 2, and risk 1) DMFT: risk 4 (n=41), risk 3 (n=41), risk 2 (n=41), and risk 1 (n=41).

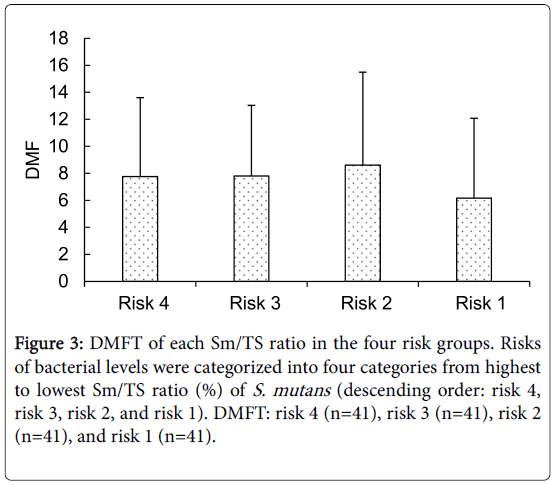

The number of DMFT relating to the Sm/TS ratio (%) in the four risk groups [risks 4, 3, 2, and 1 (n=41 each)] were 12.90 ± 5.24, 8.46 ± 5.81, 4.78 ± 4.15, and 4.20 ± 4.36, respectively, demonstrating significant differences among these classes (p<0.01, Bonferroni test, Figure 3).

Figure 3: DMFT of each Sm/TS ratio in the four risk groups. Risks of bacterial levels were categorized into four categories from highest to lowest Sm/TS ratio (%) of S. mutans (descending order: risk 4, risk 3, risk 2, and risk 1). DMFT: risk 4 (n=41), risk 3 (n=41), risk 2 (n=41), and risk 1 (n=41).

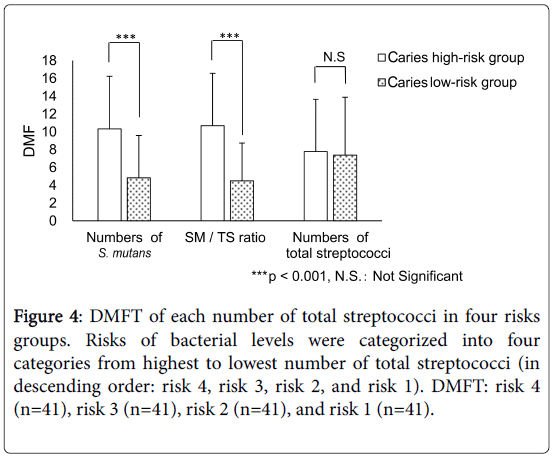

The number of DMFT relating to the number of total streptococci in the four risk groups [risks 4, 3, 2, and 1 (n=41 each)] were 7.76 ± 5.85, 7.80 ± 5.23, 8.61 ± 6.88, and 6.17 ± 5.91, respectively, indicating no significant differences among these classes (NS , Bonferroni test, Figure 4).

Figure 4: DMFT of each number of total streptococci in four risks groups. Risks of bacterial levels were categorized into four categories from highest to lowest number of total streptococci (in descending order: risk 4, risk 3, risk 2, and risk 1). DMFT: risk 4 (n=41), risk 3 (n=41), risk 2 (n=41), and risk 1 (n=41).

Discussion

Total streptococci are broadly grouped into mutans streptococci and three other species, i.e., S. mitis, S. salivarius, and S. sanguis. They constitute a majority of bacteria found in the mouth [27,29]. Of the total streptococci, the group of bacteria that primarily causes dental caries is mutans streptococci, which consists of seven species [28,36-38]; S. mutans is the mutans streptococcus most strongly associated with dental caries [5,28,39,40]. Results from the comparative control groups of the present study in adults suggested a weak association between total streptococci and presence of dental caries.

S. mutans infections in humans can begin with eruption of teeth [2,27]. In most infants, infection is transferred from the mouths of family members, particularly the mother [41]. S. mutans then colonizes the tooth surfaces and increases with age. S. mutans is detected in a vast majority (>90%) of adults regardless of their country, race, sex, eating habits, or presence of dental caries [27]. Several clinical studies have reported a clear relationship between S. mutans levels in the saliva and the development of dental caries in populations with a relatively high risk of dental caries [42,43]. In this study, for comparison with simple culture kits utilized in clinical studies and at the chairside, these similar agar medium (culture medium) is used In addition, the proportion of salivary S. mutans is significantly higher in patients with active caries than in those who are caries-free. Similar results have also been demonstrated in the dental plaque of children [44,45].

Saliva tests, which involve stimulating saliva production within a few minutes of chewing, are often performed in clinical studies [28,30]. Basically, mutans streptococci alone exist on the surface of teeth. When collecting stimulated saliva, dental plaque on the surface of teeth is rubbed off while chewing gum and wax, which allows the quantification of bacteria that have fallen off into the stimulated saliva [27,33]. When plaque is used as a sample, it is difficult to maintain a constant collection quantity, and the data obtained are unstable; therefore, saliva is more commonly used as a sample instead of plaque [2,28-30]. The issue with the previous method of measuring the quantity of bacteria from plaque was resolved by collecting plaque that is aggressively rubbed off the teeth surface by brushing to measure the quantity of bacteria therein [31].

The accurate evaluation of S. mutans levels is necessary to gain a precise understanding of the cariogenic strength of an individual’s plaque and to evaluate the proportion of S. mutans (cariogenic bacteria ratio) within it. Therefore, it is vital to identify people with highly cariogenic plaque in advance as being at a risk of dental caries, to create a plan to control and prevent dental caries, along with the implementation of control and prevention after treatment [2,27,30].

In the present study conducted in adults, when classified further into three subgroups (caries-active, caries-medium, and caries-free), the Sm/TS ratio was significantly associated with caries risk and was more useful than the number of S. mutans for the selection of high-risk subjects.

There are various ways to prevent and manage S. mutans -related dental caries, depending on individual patient’s risk level [2,27]. Therefore, it is necessary to establish individual prevention and management programs that are suitable for the risk factors identified through an appropriate assessment [2,27]. It is extremely important to perform preliminary screening of patients who are at a high risk of developing dental caries. After a caries risk assessment, a caries prevention plan can be prepared to facilitate prevention and management of caries.

Once S. mutans infection occurs in the mouth, it is difficult to remove or reduce it. The most effective way of removing or reducing S. mutans infection/colonization is to physically treat the plaque with professional mechanical tooth cleaning and to chemically control plaque formation [2,33]. In other words, when considering the costs and invasiveness of the eradication treatment, it is important to accurately diagnose S. mutans infection levels and to perform treatment in high-risk subjects alone.

When subjects were classified into groups based on Sm/TS ratios and numbers of S. mutans, similar differences were observed in the experience of dental caries. However, in the more detailed four-group risk classification, the Sm/TS ratio was more significantly associated with the experience of dental caries and was useful for the selection of high-risk dental caries subjects. A major objective of diagnosing the risk of dental caries is to detect subjects who are at a high risk of dental caries so that they can receive preventive management. It would be more effective to use the Sm/TS ratio for the detection of high-risk individuals in caries risk assessment.

This study involved no chronological analysis, and the sample size was insufficient. It is important for futures studies to be conducted in a manner that would allow chronological sampling. In our current study, we were able to collect only a cross-section of the subjects’ colonization by S. mutans, a limitation that could hinder the interpretation of our findings of the subjects’ overall risk of developing caries. Furthermore, although our findings reached significance, they should be verified using a larger, more diverse sample size to represent regional differences because many of our subjects were localized to a single region.

This study verified the use of quantitatively available plaque analysis methods and caries ratio analyses. Based on the results of such fundamental studies, a simple kit for a risk assessment that uses a culture method to detect S. mutans without using a stereomicroscope or immunochemical methods is being researched and developed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results of the present study suggested a significant association between S. mutans levels and dental caries using toothbrush plaque samples in adults. In addition, the results indicated that it would be more effective to use quantification of the Sm/TS ratio because it is superior at detecting high-risk subjects with the severity of dental caries. This approach has the potential for previous study of the development of simple culture assay for a risk assessment that may be incorporated into future clinical or epidemiological studies measures for the improvement of oral health worldwide.

Conflicts of Interest to Declare

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

References

- Griffin SO, Jones JA, Brunson D, Griffin PM, Bailey WD (2012) Burden of oral disease among older adults and implications for public health priorities. Am J Public Health 102: 411-418.

- Maheswari SU, Raja J, Kumar A, Seelan RG (2015) Caries management by risk assessment: A review on current strategies for caries prevention and management. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 7: S3204.

- Bagramian RA, Garcia-Godoy F, Volpe AR (2009) The global increase in dental caries. A pending public health crisis. Am J Dent 22: 3-8.

- Hamada S, Slade HD (1980) Biology, immunology and cariogenicity of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiol Rev 44: 331-384.

- Loesche WJ (1986) The role of Streptococcus mutans in human dental decay. Microbiol Rev 50: 353-380.

- Loesche WJ, Eklund S, Earnest R, Burt B (1984) Longitudinal investigation of bacteriology of human fissure decay; epidemiological studies in molars shortly after eruption. Infect Immun 46: 765-772.

- Beighton D, Rippon HR, Thomas HE (1987) The distribution of Streptococcus mutans serotypes and dental caries experience in a group of 5-8-year-old English school children. Br Dent J 162: 103-106.

- Beighton D, Manji F, Baelum V, Fejerskov O, Johnson NW, et al. (1989) Associations between salivary levels of Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus sobrinus, Lactobacilli and caries experience in Kenyan adolescents. J Dent Res 68:1242-1246.

- Hedge PP, Ashok BR, Ankola VA (2005) Dental caries experience and salivary levels of Streptococcus mutans and lactobacilli in 13-15 years old children of Belgaum city, Karnataka. J Indian Soc Pedo Prev Dent 23:23-26.

- Lim HH, Yoo SY, Kim KW, Kook JK (2005) Frequency of species and biotypes of mutans streptococci isolated from dental plaque in adolescents and adults. J Bacteriol Virol 35: 197-202.

-  Loyola-Rodriguez JP, Martinez-Martinez RE, Flores-FerreiraBI, Pati-o-MarÃn N, Alpuche-SolÃs AG, et al. (2008) Distribution of Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus in saliva of Mexican preschool caries-free and caries-active children by microbial and molecular (PCR) assays. J Clin Pediatr Dent 32: 121-126.

- . Kishi M, Abe A, Kishi K, Ohara-Nemoto Y, Kimura S, et al. (2009) Relationship of quantitative salivary levels of Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus in mothers to caries status and colonization of mutans streptococci in plaque in their 2.5-year-old children. Community Dent Oral Epidermiol 37: 241-249.

- Singh N, Chawla HS, Tewari A, Sachdev V (2010) Correlation of severity of streptococcus mutans in the saliva of school children of Chandigarh with dental caries. BFUDJ 1: 5-8.

- Okada M, Taniguchi Y, Hayashi F, Doi T, Suzuki J, et al. (2010) Late established mutans streptococci in children over 3 years old. Int J Dent.

- Nurelhuda NM, Al-Haroni M, Trovik TA, Bakken V (2010) Caries experience and quantification of Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus Sobrinus in saliva of Sudanese school children. Caries Res 44: 402-407.

- Okada M, Kawamura M, Oda Y, Yasuda R, Kojima T, et al. (2012) Caries prevalence associated with Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus in Japanese school children. Int J Paediatr Dent 22: 342-348.

- Nanda J, Sachdev V, Sandhu M, Deep-Singh-Nanda K (2015) Correlation between dental caries experience and mutans streptococci counts using saliva and plaque as microbial risk indicators in 3-8 year old children. A cross Sectional study. J Clin Exp Dent 7: e114-118.

- Edelstein BL, Ureles SD, Smaldone A (2016) Very high salivary Streptococcus mutans predicts caries progression in young children. Pediatr Dent 38: 325-330.

- Latifi-Xhemajli B, Véronneau J, Begzati A, Bytyci A, Kutllovci, et al. (2016) Association between salivary level of infection with Streptococcus mutans/Lactobacilli and caries-risk factors in mothers. Eur J Paediatr Dent 17: 70-74.

- Drake D, Dawson D, Kramer K, Schumacher A, Warren J, et al. (2015) Experiences with the Streptococcus Mutans in Lakota Sioux (SMILeS) Study: Risk factors for caries in American Indian children 0-3 years. J Health Dispar Res Pract 8: 123-132.

- Karjalainen S, Tolvanen M, Pienihäkkinen K, Söderling E, Lagström H, et al. (2015) High sucrose intake at 3 years of age is associated with increased salivary counts of mutans streptococci and lactobacilli, and with increased caries rate from 3 to 16 years of age. Caries Res 49: 125-132.

- Saraithong P, Pattanaporn K, Chen Z, Khongkhunthian S, Laohapensang P, et al. (2015) Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus colonization and caries experience in 3- and 5-year-old Thai children. Clin Oral Investig 19: 1955-1964.

- Abbate GM, Borghi D, Passi A, Levrini L (2014) Correlation between unstimulated salivary flow, pH and Streptococcus mutans, analysed with real time PCR, in caries-free and caries-active children. Eur J Paediatr Dent 15: 51-54.

- Very high salivary Streptococcus mutans predicts caries progression in young children.

- Association between salivary level of infection with Streptococcus mutans/Lactobacilli and caries-risk factors in mothers.

- Experiences with the Streptococcus Mutans in Lakota Sioux (SMILeS) Study: Risk factors for caries in American Indian children 0-3 years.

- Axelsson P (2000) Diagnosis and risk prediction of dental caries. Quintessence,lllinois.

- Guo L, Shi W (2013) Salivary biomarkers for caries risk assessment. J Calif Dent Assoc 41: 107-118.

- Parisotto TM, Steiner-Oliveira C, Silva CM, Rodrigues LK, Nobre-dos-Santos M (2010) Early childhood caries and mutans streptococci: a systematic review. Oral Health Prev Dent 8: 59-70.

- D'Amario M, Barone A, Marzo G, Giannoni M (2006) Caries-risk assessment: the role of salivary tests. Minerva Stomatol 55: 449-463.

- High sucrose intake at 3 years of age is associated with increased salivary counts of mutans streptococci and lactobacilli, and with increased caries rate from 3 to 16 years of age.

- Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus colonization and caries experience in 3- and 5-year-old Thai children.

- Correlation between unstimulated salivary flow, pH and Streptococcus mutans, analysed with real time PCR, in caries-free and caries-active children.

- Salonen L, Allander D, Bratthall D, Hellden L (1990) Mutans streptococci, oral hygiene and caries in an adult Swedish population. J Dent Res 69: 1469-1475.

- World Health Organization (1997) Oral health surveys: basic methods. (4thedn), World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Van Houte J (1994) Role of microorganisms in caries etiology. J Dent Res 73: 672-681.

- Batoni G, Ota F, Gheraldi S, Senesi S, Barnini S, et al. (1992) Epidemiological survey of Streptococcus mutans in a group of adult patients living in Pisa (Italy). Eur J Epidemiol 8: 238-242.

- Nishikawara F, Katsumura S, Ando A, Tamaki Y, Nakamura Y, et al. (2006) Correlation of cariogenic bacteria and dental caries in adults. J Oral Sci 48: 245-251.

- da Silva BastosVde A, Freitas-Fernandes LB, Fidalgo TK, Martins C, Mattos CT, et al. (2015) Mother-to-child transmission of Streptococcus mutans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent 43: 181-191.

- Neta T, Inokuchi R, Shinozaki-Kuwahara N, Kouno Y, Ikemi T, et al. (2002) Investigation of microbiological methods to estimating individual caries risk: Evaluation of sampling methods and materials. Int J Oral-Med Sci 1: 29-32.

- Zhi QH, Lin HC, Zhang R, Liao YD, Tu JZ (2007) Arbitrarily primed-PCR detection of Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus in dental plaque of children with high DMFT and no caries. Zhonghua Kou Qiang Yi XueZaZhi 42: 219-222.

- Choi EJ, Lee SH, Kim YJ (2009) Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction for Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sobrinus in dental plaque samples and its association with early childhood caries. Int J Paediatr Dent 19: 141-247.

Citation: Gotouda H, Shinozaki-Kuwahara N,Taguchi C, Shimosaka M, Ohta M, et al. (2017) Evaluation of the Proportion of Cariogenic Bacteria Associated with Dental Caries. Epidemiology (Sunnyvale) 7: 327. DOI: 10.4172/2161-1165.1000327

Copyright: © 2017 Gotouda H, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 4971

- [From(publication date): 0-2017 - Apr 03, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 4069

- PDF downloads: 902