Evaluating End-of-life and Medical Assistance in Dying Communication Learning - A Literature Review

Received: 30-Jan-2023 / Manuscript No. jpcm-23-88861 / Editor assigned: 01-Feb-2023 / PreQC No. jpcm-23-88861 (PQ) / Reviewed: 15-Feb-2023 / QC No. jpcm-23-88861 / Revised: 20-Feb-2023 / Manuscript No. jpcm-23-88861 (R) / Accepted Date: 25-Feb-2023 / Published Date: 27-Feb-2023 DOI: 10.4172/2165-7386.1000501

Abstract

Aim: Our literature review assesses the available End of Life (EOL) and Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) communication training for clinicians and trainees. By analyzing training program evaluations, we assess their impact to learners’ practice and improvements to patient care. We then highlight the effective training programs, which could be considered to support further development of continuing education curriculum for EOL and MAiD discussions.

Background: Healthcare providers are facing an ongoing need for education in EOL communication with patients and families to support patient-centered care. Since legalization of MAiD in 2016 in Canada, number of patients seeking this option is growing. Currently, there is no widely accessible, standardized EOL or MAiD discussion curriculum to support clinicians of diverse experience levels. While jurisdiction or profession-specific training is available to some providers, it is unclear whether it translates to improvements in their practice or patient care.

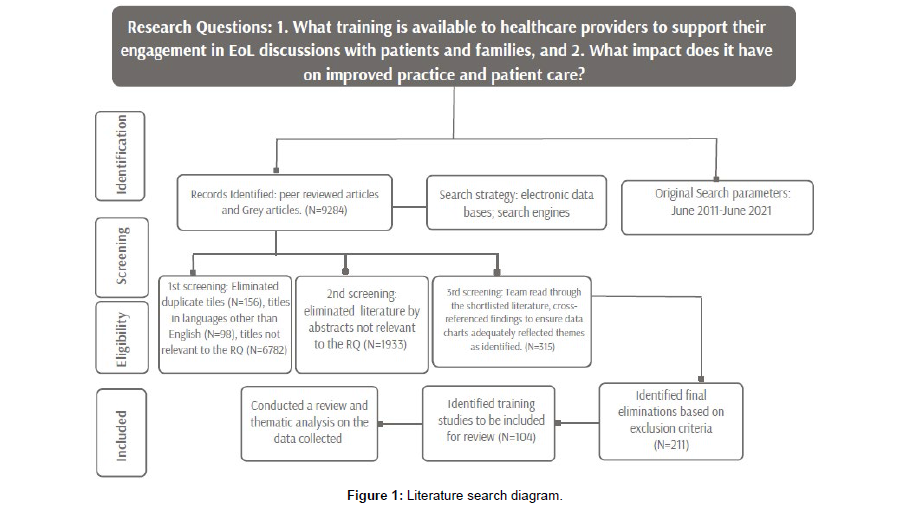

Methods: We conducted a peer-reviewed and grey literature search on the topics of EOL, palliative care and MAiD-related training for healthcare providers and trainees. We targeted resources published between June 1, 2011 and June 1, 2021, in English language, worldwide. Using rapid review protocol, initial search of 9284 titles was shortlisted to 104 training programs offering training on EOL discussions with adult patients and their families. Using CRe-DEPTH framework our team evaluated the reported impact of the training.

Results: Limited scope of evaluations of most training programs posed challenges to determine their longer-term benefits to practitioners and patients, or to define which teaching approaches were the most impactful. Interdisciplinary learning helped to validate the results of some training programs, suggesting benefits of the approach in teaching EOL/MAiD discussion curricula. Despite the challenges, many great training programs emerged from the field that could serve as starting points to build high quality EOL and MAiD communications training.

Keywords

MAiD; End-of-life care; Communication; Education; Healthcare providers

Abbreviations:

EOL: End of Life

MAiD: Medical assistance in dying

Background

Ever since end-of-life (EOL) care became a distinct field in healthcare, professions, such as nursing, social work, spiritual care and physicians have seen their traditional scope of practice and responsibilities evolve to engage in EOL care. Clinicians in this field partake in and facilitate discussions with patients and their families in delivering prognoses, transitioning from curative to palliative treatments, and establishing patients’ goals of care in accordance with their final wishes and values. Such conversations are frequently complex in nature, and require sustained skilled communications. Even though EOL-related discussion skills are now essential for clinicians in this field, there is no widely accessible standardized communication training that prepares them to engage in these discussions. Training programs that emerged from the field aren’t all built to enhance and support clinicians’ skills across diverse environments that might require knowledge-sharing or interdisciplinary llcooperation [1 -3].

MAiD: In Canada, medical assistance in dying (MAiD) has been a part of the EOL landscape since it became legalized in February of 2016 [4]. It is an aspect of EOL care that sees a growing demand from the patients: in 2021 alone, 10,064 people used this option for their end-oflife journey, an increase of 34.3% over 2020, and accounting for 3.3% of all deaths in Canada that year [4]. Since the legalization of MAiD, various challenges have emerged as clinicians develop approaches to integrating this new aspect of healthcare into their work, such as preparedness, personal attitudes, ethical dilemmas and navigation of patient and families’ dynamics or required medical protocol [5,6].

At present, clinical guidelines and legislation-focused resources for MAiD exist at the individual care-facility, local or regional levels, as well as those developed by practitioner organizations, such as the Canadian Association for MAiD Assessors and Providers.

There is a growing alignment and overlap in practise for EOL care-focused specialties [7,8], it is therefore expected that clinicians entering and working in this field will have common educational needs to improve and support their communication skills while interacting with patients and their families. A high quality, widely accessible EOL conversations curricula could also inform the development of educational programs supporting the provision of MAiD.

Our Study

Our study seeks to identify what learning opportunities currently exist for health care professionals and trainees to support their engagement in EOL discussions with patients and families, as well as to evaluate the ability of those opportunities to improve their practice, and, in turn, patient care. A strong need for such education to be accessible, continued and in alignment with the needs of clinicians and patients has been identified by earlier research [1,2,9]. It is therefore important to evaluate the effectiveness of the available EOL discussion training capacity to respond to these needs and to help inform the ongoing development of standardized EOL communication curricula.

Methods

Definitions

Hui et al. [10] reference the end-of-life stage of someone’s life trajectory as a period of time where they are living with, and are impaired by, an inevitably fatal condition, although duration of that period is ambiguous. In such a time, the patient, their family and their clinical support teams might be engaging in advance care planning and EOL discussions. Our study focuses on the clinician discussions that occur in the period referenced by Hui et al., and includes, but is not limited to the following: Serious Illness Conversations [11], Goals-of- Care [12], Advance Care Planning [13], breaking bad news [14], and conducting an EOL family meeting [15]. Additionally, we gave a special consideration for training in MAiD discussions, as this is an evolving and important EOL consideration in Canada and other jurisdictions where it has been legalized.

Evaluations of training

During the early considerations of our study, preliminary searches returned a myriad of training interventions and resources aimed at EOL clinicians and students that offered skill-building in diverse aspects of their practise. Ability to effectively communicate with patients and families is essential to quality EOL care. But same is as important for the interdisciplinary teams of providers working to achieve consistency of supports for their patients [9,16]. Our systemic review serves a two-fold purpose-to help identify whether and what EOL discussion training is available to clinicians, and what impact might it have on their practises to benefit those in their care.

Van Hecke, et al’s. [17] CRe-DEPTH framework for reporting and evaluating training in healthcare relies on the quality of descriptions of training details, such as objectives, measured outcomes, and validity of post-training assessments, among others. We utilized CRe-DEPTH to analyze the descriptions and author-provided accounts of the training we reviewed, particularly in relation to rationale for chosen delivery methods and populations, validity and reliability of training’s impact. The framework provided a baseline structure for our evaluations, which then lead to identifying a number of themes present in the creation of and reporting on the EOL discussion training.

Systemic review

We conducted an extensive literature search on the topics of EOL, palliative care and MAiD-related training for healthcare providers. The search was performed in collaboration with the University of Victoria (Victoria, BC, Canada) library services, querying databases and catalogues (EBSCO CINAHL Complete, MEDLINE, PSYCHINFO, PROQUEST Dissertations Global, ERIC, SAGE Knowledge, SPRINGER Link and WorldCat). Search terms were set for English language literature, published in full-length, with keywords such as “hospice care”; “palliative care”; “hospice and palliative care nursing”; “MAiD”, “terminal care”; “communication”; “health communication”; “family meeting”; “shared decision making”; “education” among others. In order to capture as many published resources as possible, we selected a 10-year period for our review: works published between June 1, 2011 and June 1, 2021, anywhere in the world. The search returned 9,284 unique titles of academic articles and Grey Literature.

Under rapid review following PRISMA method (Figure 1), the team then narrowed the initial body of literature to training programs on EOL and/ or palliative care for providers or trainees where EOL discussions with adult patients and families were part of the learning initiative. We focused on adult patients, as our team at the time was based within a hospice serving patients over 18 years of age.

The healthcare disciplines we included were: medicine (all specialties), nursing (all specialties), social work, psychiatry, psychology, gerontology and spiritual care. We ended up including 104 published EOL training programs that contained communication learning. We then reviewed the programs and catalogued the pertinent data, which eventually led to surmising several emerging themes in how the programs are designed, evaluated and what is reflected in their results.

Analysis

Overview: For the purposes of this review, we identified 104 published programs and learning initiatives containing EOL communication training over the 10 year period. Table 1 categorizes the studies by targeted professions, geographic area and learning delivery. EOL communication training is offered at a variety of settings, including academic, hospitals, hospices, long-term-care and community environments.

| Communication training programs | N=104 |

|---|---|

| Countries | N=13 |

| USA | 13 |

| UK | 8 |

| Australia | 7 |

| Canada | 3 |

| Belgium | 3 |

| Japan | 2 |

| New Zealand | 1 |

| Thailand | 1 |

| Hong Kong | 1 |

| Switzerland | 1 |

| The Netherlands | 1 |

| Taiwan | 1 |

| Germany | 1 |

| Target Professions | |

| Family Medicine | 53 |

| Nursing | 47 |

| Medicine - Specialties | 25 |

| Social work | 30 |

| Psychology | 10 |

| Other | 19 |

| Learning Delivery | |

| Inter-professional training programs | 30 |

| Simulated learning | 39 |

| Field placement | 30 |

| Mentoring | 21 |

| Longitudinal evaluations (min. 1 month) | 11 |

| Programs involving patients | 7 |

| Programs involving families | 1 |

Table 1: End-of-life care training programs by geographic area, professions and learning delivery.

Family physicians were the profession that received most of the offered training: fifty three programs targeted family medicine, followed by nursing, with forty seven offered programs. Most programs included some form of experiential EOL discussion learning, frequently using simulation, video recordings or role-play. Thirty of the initiatives involved placing providers or trainees in their field for practice, and twenty one involved mentoring with senior members of the interdisciplinary teams. Training on EOL discussions with families was not provided separately, but included alongside the wider training with patients. Seven programs incorporated some form of patients’ feedback or participation in the training, and one program engaged patients’ families. Eleven programs offered a longitudinal evaluation on the providers’ skill sustainment, with the follow-up ranging from 1 to 12 months following program completion.

Findings

EOL discussion training is offered through diverse means, settings and approaches, from university curricula or institution-specific workshops, to self-paced online modules. Authors’ reporting on the learning their programs offered also varies greatly. CRe-DEPTH [17] was our go-to framework to assess the various programs for what has been reported on and whether the reports allow to discern effectiveness of the education for its ability to impact learners and their patients, or sustain the gained skills. Throughout our review, the following themes emerged in the reporting: Authors’ evaluations of their programs; Validity of the results; Incorporating patient (and family) perspectives; and Inter-professional education and collaboration.

To discuss the findings of this review, we identified the most representative examples of training programs within the 104 educational interventions we shortlisted. Some of the programs fall into multiple themes and are pertinent to several aspects of our analysis, while others support the information already discussed. Therefore not all 104 programs are referenced, rather examples that represent a comprehensive summary of findings discussed. Those that were not referenced are programs that do not present new information.

Authors’ evaluations of EOL communication training

CRe-DEPTH [17] references the importance of defining the intentions of the training, focusing on learners’ ability to perform the competencies they’re seeking to gain. Additionally, intervention needs to be clear on what exactly it is teaching and how the selection of teaching methods will help to achieve the learning objectives in a way that would allow for efficacy to be validated. The validation could be applied in multiple levels, starting with measuring trainees’ reactions to training (level 1), changes in their competences (level 2), behaviour (level 3), and changes impacting organizational level, which could include patient outcomes (level 4). With this in mind we examined the authors’ descriptions of training evaluations, and how those reflect the intent and development of the training, participants’ satisfaction with what they learned, and, the benefits to their practice. We considered who provided the evaluation and what criteria have been weighted.

Overall, the majority of training programs we reviewed were evaluated via learner self-assessments and less frequently by measuring the impact on patients, or the improvements in patient care [18- 20]. This was particularly evident in training aimed at early-career practitioners and trainees, where the evaluations tended to focus on satisfaction with the training and self-reported improvements in confidence, knowledge, attitudes, and preparedness to engage in EOL discussions [21,22]. Many short-term initiatives or purposedesigned clinical tools were deemed effective and appropriate solely based on such feedback, even though their impact on providers’ work was never measured [23-26]. The means of evaluations often were questionnaires, surveys or online forms, collected immediately following the completion of the training. Applying CRe-DEPTH [17], most evaluations of EOL training would fall within the validation levels 1 and 2, without additional, more comprehensive assessments or follow-up on learners’ behaviour or organizational impacts. This makes it challenging to evaluate the potential benefits of these programs to clinicians’ practice, as previously observed in research on EOL-related clinical training [1,2,27]. Several programs accomplished measuring their impact and outcomes in a manner which would satisfy CRe-DEPTH-referenced [17] levels 3 and 4 by establishing procedures of tracking learner improvement and skill utilization. Examples of such studies include Harwell [28], Levine et al. [29] and Buller, et al. [30]. Additionally, Samala et al. [18] utilized a unique approach of juxtaposing learners’ reflections from their field-work against skills taught in curriculum for simultaneous evaluations of benefits to the learners’ day-to-day practice. What could be gleaned from the evaluations based on participants’ feedback is that EOL training for both new and experienced practitioners is useful and welcome. Learning which offered interactive, diverse, inter-professional modalities was particularly engaging for attendees [31]. Training that involved experiential opportunities, field placements and mentoring was perceived as the most impactful and served as a strong basis for learner enthusiasm about what and how they learned [2,29,32]. However, the paucity of studies measuring patients’ experiences with provider education is notable. Considering that simulation teaching may not accurately reflect learners’ skill-levels with patients [18,27], the care recipient perspectives are key to inform the improvements to care, yet, based on our findings, they appear to be under-studied. We identified three programs [33-35] which did attempt to evaluate whether patients experienced better care from providers who completed the training. In two of those studies, Pollak, et al. [33] and Nussbaum, et al. [35] recorded no measurable changes in care improvements after the training. The third study, Johnson et al. [34] reported that patients previously involved in a goals-of-care educational program for hospitalists saw fewer emergency department readmissions and better emotional care during their EOL decisionmaking. However, authors noted that these promising results could not be solely accredited to the educational program that patients once participated in. Additionally, none of the training interventions reviewed for this paper were designed to measure the experiences of EOL patients’ families. While few EOL discussion training programs were developed with the intention to measure their impacts on patients, we identified a higher number of programs that engaged patients in other ways [33,35-38]. Patients as co-educators is one of the more common, meaningful opportunities to benefit from the voices of those in care [1]. Some programs hosted care recipients acting as test patients and assessors of learners’ ability to start EOL discussions, and uphold patients’ values and choices [39]. Patient involvement is also noted in various types of informal training via everyday interactions, resulting in patient-centered mentoring of the learners within their respective disciplines and inter-professionally [37]. Similarly, patient feedback is used to inform clinicians’ competencies or identify skill gaps in practice [27,36]. EOL patients families’ involvement in communication training is very rare. In the sole study we identified, Schillerstrom, et al. [40] engaged families as stakeholders in establishing clinicians’ educational needs, as well as defining collaborative strategies to improve care and communications. According to families, as learned in past research, effective clinician communication is one of the key pre-requisites to successful EOL care [40,41] and it should be reflected in the evaluation of training programs as a means of assessing more advanced levels of impact. Our review suggests that majority of available EOL discussion training may not be developed with the intent of more advanced evaluations, beyond the immediate learners’ feedback related to satisfaction and attitudes. Nonetheless, eight programs [33-40] took steps to include care recipients’ insights to gain more robust understanding about the benefits of the training. Determining validity of training results CRe-DEPTH [17] recommends that the means of measuring the trustworthiness of study results be considered at the development level. Also, relations between the contexts, mechanisms and outcomes of training must be clear, allowing to validate the methodological strengths of the intervention. It also recommends defining rationales when training requires tailoring to particular competency levels and settings. Evaluations of training studies we reviewed in the previous section suggested that most training programs were not designed to allow for more advanced assessments and, likely, further validations of the results. Of the studies we reviewed, eleven of them implemented post-training evaluations of longitudinal skill sustainability ranging between 1 and 12 months follow-up.

Analyzing authors’ rationale for the training development, many note that their interventions have been created out of urgency for EOLrelated training, including that of communication, in various care institutions, settings, locales and professions. However, the efficacy of such training was challenging to validate because often the programs were intended for a single organization, unit or profession [18,19,42- 44], or scope of evaluations was restricted by small samples, or limited to participants’ self-selection to report [18,20]. Most training programs reviewed were not designed to be tested whether their education brought measurable benefits to practise, or whether it would be transferrable outside of the original settings [45-47]. In most cases, authors of studies did not include validity measures in the published descriptions of their training. We also did not find any follow-up studies validating or replicating previous initiatives in order to adapt or test them in different settings.

Studies that were designed to validate their results often were associated with a well-established, formal and measurable EOL care curriculum and strong institutional support [2]. Examples include Harwell [28], Levine, et al. [29], von Gunten et Al. [32], and Taylor [48] among others. Collingridge et al., [3] suggest that challenges arising from tight research study timelines, funding and logistics affect the design and execution of EOL training, and might be behind the limited opportunities for authors to implement more in-depth validations and follow-ups. Our review indicates these challenges will likely continue to persist.

Some authors of programs proposed other creative ways to validate their training results. Some programs tested how transferrable their learning was to other disciplines in care teams by enabling interdisciplinary knowledge transfers as part of the training. Others offered supportive post-learning follow-up for providers. Among the examples, Head et al’s. [49] inter-disciplinary workgroups and co-mentoring ensured learners built awareness of other disciplines’ work and obligations. Paladino et al. [50] and Mott et al. [51] designed processes to track their learners sustained skill application in their practise and further learning; and Beattie [20] et al. tracked the continued use of their conversation-based screening tool, available as part of the training, in the interdisciplinary teams of their former participants.

Three studies focused on a niche-area of training for specialists or providers engaged with particular groups of patients [32,48,52]. By their nature, these studies may not be generalizable outside of their niches, but authors provided strong rationale for the need of specialized training, and delivered well-supported results. Levine et al. [29] showed how the providers were enabled to bring care improvements into settings with different levels of available resources, underlining the importance of validity measures.

As for MAiD: Our review identified no published evaluations of MAiD-specific training programs, and only one scoping review referencing the incorporation of this topic into EOL discussion curricula. This is possibly due to the relatively recent development of MAiD legislation, education and training. While many such resources are created specifically for geographic areas or institutions, they are not yet published and evaluated as training programs. In their review, Kelley, et al. [53] referenced MAiD training created in Europe in 2002, concluding that it did not change learners’ attitudes and knowledge of the subject. At that time only 4 countries had some form of medical assistance in dying legalized - Belgium, Netherlands, Luxemburg and Switzerland. Our review did not identify any more recent training programs aimed at providing MAiD education to healthcare providers.

EOL curricular materials are informing and assisting the development of MAiD education. Gewarges, et al. [54] created a framework to supplement the curriculum of medical schools, which is centered around EOL patients seeking MAiD and involves diverse modalities of learning, such as case-based studies, interdisciplinary collaborations, mentoring and interactions with patients. Gewarges et al.’s proposed framework was the most extensive MAiD-specific curricular approach we identified, and, although, not yet tested in the field, it offers a high threshold of quality for MAiD education. Other examples include LeBlanc et al. [55]; Li et al. [56] and others.

Discussion

Educational approaches

Post-secondary education system and workplaces are responding to the need for EOL discussion education for healthcare providers of all levels of experience. The training we reviewed was created for a range of professions and involved university curricula, continuing education and on-the-job training. The learning offered ranged from semester coursework, to one-off workshops, to specific toolkits to aid healthcare workers in communicating with their patients at end-of-life. Yet, from this diverse learning, its different goals, designs and reported results, it is hard to pin-point which approaches and their intended outcomes might actually work for clinicians to improve their practise [1]. The limited evaluations of most studies reviewed, did not discuss longterm effect of training for providers, or translation of skills learned to improved patient care.

Our findings did support earlier research, that most extensive training programs are geared towards early career practitioners, and opportunities to learn decrease as one’s experience advances, despite the changes to their professional responsibilities [1,2]. Established curricula and high level of supports in learning is often present in postsecondary education training, while workplace-based learning, which would be more available for experienced clinicians is frequently offered through single-event initiatives, where association with the program ends once training is completed.

The ad-hoc on-the-job learning is often built as a response to a specific need, at a particular setting or involving select group(s) of providers [18,19,42-44]. Although it offers solutions in the moment, its nature creates challenges to validate the training outside its original contexts. This model would not necessarily support longitudinal skill building at diverse levels of practitioner experience, or overcome the institutional or personal barriers that may limit training’s impact on practitioners and patients [34,57,58]. Frequently, authors of the programs note the necessity to test their training further and apply it to different scenarios [45-47]. Despite that, none of the training programs were replicated and tested by another study for their own validation.

For the purposes of informing a widely accessible, relevant and standardized EOL discussion learning for health workers, it would be imperative to identify specific approaches which may have helped to achieve the educational efficacy. Studies which could be assessed at the higher levels referenced in CRe-DEPTH framework [17] would offer a more comprehensive understanding of their impact.

Few studies attempted or succeeded to measure their impact on patients, suggesting that patient-focused training might need to be prioritized in order to create a better understanding of impactful educational approaches [27]. Following Collingridge, [3] our findings reflect a call for organizations to not simply provide education opportunities, but to implement a process that evaluates and supports skills long-term, to benefit the providers and recipients of care [25,36,59-62].

Despite the validation challenges in the reviewed EOL discussion training, a strong reoccurring theme emerged from the perspective of the care providers, indicating a desire for ongoing learning opportunities and skills practice [26,62-64]. Insights gleaned from the strengths and weaknesses of the reviewed studies could inform robust curriculum development in EOL and MAiD.

MAiD-focused education has not been in the forefront of the recent educational programing. Two European studies on the subject date back to 2002 reporting mixed results in their learners’ skill acquisition [53], yet showing potential in improving their confidence. These findings relate to later research, calling for stronger methodologies and more rigorous evaluations in clinician education of the EOL fields, which would reflect impacts on the quality of patient care [1-3].

Interprofessional collaboration

Where training program methodology and design may not have included advanced evaluations, some authors who involved multidisciplinary teams managed to create a layer of validation through collective knowledge sharing. At the end-of-life, patients are cared for by a range of health care professionals. Communication provides essential link within the care teams and supports collaborations for continuity of care [9,41]. Head, et al. [49] and Levine, et al. [29] were very successful in creating interdisciplinary environments, where results of their studies were supported in significant ways across different levels of experience, structures and resource availability. Examining more training programs, we found that learning, when delivered inter-professionally allows for more thorough validation of skill gains in different settings, professions and organizational hierarchies, by inherently “testing” the training in more varied contexts. Starks, et al.’s [45] inter-professional training curriculum enabled to create an informal alumni support network, which allowed for a form of tracking past learners’ practice advances and continued learning with their peers, even though the program was not designed for advanced evaluations post-course. Graham, et al.’s [65] findings supported the strengthening of competencies learned through inter-professional field placements, where learners not only improved the EOL discussion skills necessary to their roles, but also, developed stronger understanding of their teammates’ responsibilities. And Neuderth, et al’s. [66] training program involved feedback given by peers to those outside of their profession, furthering their knowledge gains across the team.

Applying CRe-DEPTH [17], interdisciplinary collaborations impact at least two levels of evaluation: competences (level 2), and behaviour (level 3) by creating feedback loops and team support microsystems, which may not have been intended to capture in the designs and evaluations of many training programs. Our findings support the benefits that inter-professional education lends to learning and potentially, future improvements in practise [1,9,29].

Summary of findings and Conclusion

Our review seeks to determine what training is available to clinicians and trainees in EOL and MAiD discussions with patients and their families. It also aims to assess what impact that training may have on improvement of practise and patient care. We conducted a literature review focused on published training programs, which have been evaluated by their authors. We used CRe-DEPTH [17] framework to assess the extent of evaluations and validations of the training results.

The majority of training programs evaluate learners’ attitudes about the subject they’re learning and their satisfaction with the training received. Some programs also assessed competencies. About one-in-ten of the reviewed programs were designed for more extensive evaluations and validations, tracking their learners’ progress longitudinally or allowing for adaptations to other settings. Those programs appeared to be backed by strong institutional support. Most training programs were created to address specific educational needs in particular professions or institutions, were brief in delivery and offered no follow up assessments. We didn’t flag any new training programs attempting to replicate and validate the results of earlier programs.

One-in-thirteen programs engaged patients and families with the training, and three studies attempted to measure their impact on patient care. This suggests that care recipients’ perspectives could be prioritized in clinical education research in the future.

Inter-professional training offers an additional layer of validation for learning, by allowing knowledge-sharing as a way to further support gained skills. Knowledge-sharing also assists with testing the skills outside of the original settings and intentions of the training.

Finally, EOL discussion training is needed and welcome in the field, and programming that offers experiential and inter-disciplinary learning, was the most revered by the participants. There is a desire for institutionally-supported, accessible and relevant EOL communication learning, that could serve practitioners of diverse experience levels.

Outstanding studies

While seeking to inform the creation of such curriculum, it is too difficult to pin-point which learning approaches might be the most effective, since most training program designs are affected by the validation challenges. However, our review allowed for highlighting outstanding studies that could serve as concepts towards building a widely accessible EOL discussion curriculum. They are also inspiring success stories of effective training and responsible research, which could influence methodological direction of future programs. These programs frequently used accredited generalist or specialty curricula and proved their benefits through rigorous evaluations [28,29,32]. They also provided immersive learning, including inter-professional collaborations [18,28,32,66]. Many enabled opportunities to deploy learning in other settings, professions or cultures [20,36,49]. Some engaged the care recipients or sought their experiences [33-36,40]. Studies designed for specialists used in-depth evaluations to report learner progress and build on existing expertise [32,48,52].

Table 2 includes examples and details of outstanding studies we noted.

| Authorship | Program reference # | Country | Target profession(s) | Outstanding features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samala, et al. | 18 | USA | Medicine | Unique methodological approach of assessing learners’ self-reflections against skills taught in training, to track their day-to-day improvements while on duty. |

| Beattie, et al. | 20 | Australia | Various: Oncology unit clinicians | Interdisciplinary training that offered a generalizable screening tool, which served as an additional layer of tracking learners’ improvements. |

| Harwell J. | 28 | USA | Nursing | Specialist training, using well-supported curriculum (ELNEC) and demonstrating how it can be tailored and effectively measured for its benefits in EOL care |

| Levine, et al. | 29 | USA | Medicine and nursing | Program engaged medicine fellows and experienced nursing staff, proved its efficacy through multi-tier evaluations, longitudinal progress tracking and participant feedback. It also involved immersive IPE, field-placements and inter-professional mentoring. The study was particularly effective and responsive in augmenting support for learners facing risk of burn-out in community-based hospitals. |

| Von Gunten, et al. | 32 | USA | Medicine: primary and internal | This program followed-up with learners using methods from the national residency education project after the training and upon completion of their residency. It offered immersive learning and in-depth progress tracking. Interestingly, evaluation of this study identified an ‘‘arrogance–ignorance’’ paradox, where senior medical residents and faculty reported significantly greater confidence to perform palliative care and lower concern about ethical and legal issues than junior-level residents, out of proportion with the negligible differences in their measured knowledge. |

| Pollak, et al. | 33 | USA | Medicine | Unique methodological approach to measuring benefits to patients, who were part of provider training |

| Johnson, et al. | 34 | UK | Various | Interdisciplinary program, which enabled generalization across settings and included measuring its impart on patient care. |

| Nussbaum, et al. | 35 | USA | Medicine | Immersive learning, rigorous multi-tier evaluations and engaging patients as co-educators sought to assert their values and preferences. |

| Sharma, et al. | 36 | USA | Various, involved in EOL | Intensive coaching program used recorded interviews with patients and clinicians to improve goals-of-care communication. In addition to engaging patients’ voices and enabling knowledge-sharing to different settings, the study identified that clinicians frequently missed opportunities to progress from information delivery to patient support. |

| Head, et al. | 49 | USA | Medicine, nursing and social work | Training results were validated via informal interdisciplinary knowledge-sharing and feedback, in additions to pre-designed evaluations. |

| Tuffrey-Wijne, et al. | 52 | UK | Various, involved with patients with intellectual disabilities | Effective, specialized training model for delivering bad news to patients with intellectual disabilities. |

| Neuderth, et al. | 66 | Germany | Medicine and social work |

The program was successful in fostering inter-professional respect, knowledge sharing and improved communication among the professions involved, as well as to jointly support their patients. |

Table 2: Examples of outstanding studies.

Recommendations

Our findings identified several opportunities for future directions in education on EOL and MAiD discussions. Patient-centered educational programs and research should be strongly prioritized given the paucity of care recipients’ voices in the training programs we reviewed. As key stakeholders, patients and their families should have a say in whether the providers’ approach to care is improved by education or skill training.

Considering how many new initiatives have emerged in the field, it is imperative for future research to validate the outcomes of existing training, especially in how it may be duplicated in other settings. Many novel interventions offer the necessary solutions and appear to have potential for more widespread use, yet their benefits remain unclear because of their short-term design and limited evaluations. Validating previous training would also help identify the most impactful method of educational offerings.

Interdisciplinary learning could aid significantly in clinician skillbuilding. The potentials that inter-professional education has should be explored in the clinical learning environment. Educational initiatives might benefit by prioritizing inter-professional learning, especially in settings facing resource challenges.

Further, the scarcity of new, relevant MAiD-focused training opens the opportunity for both generalist and specialty training initiatives to be created, to aid clinicians engaged in facilitating and delivering MAiD services to the growing population of patients interested in the option.

Lastly, organizations and educational authorities should explore how to best support ongoing, accessible relevant and, possibly, standardized professional development for learners of all experience levels to further and sustain communication skills, essential in EOL care.

Limitations

Our review holds some limitations. The rapid review protocol is reliant on accurate indexing and summarizing of articles, creating the potential for exclusion of some un-indexed educational offerings. Our search was limited to English language studies only, published between June 1st 2011 and June 1st 2021, available in full-text format. Some studies published in other languages, outside of our time-frame, or published in other formats, such as conference presentations or posters, were excluded. Also, some shortlisted literature was not accessible to the review team. Lastly, our focus was on EOL conversation training with adult only patients and families. We did not examine studies aimed at EOL conversations involving children.

Acknowledgments

We’d like to thank Simone St. Louis-Anderson, BSc, for her contributions with sourcing and cataloguing data for this project. We’d also like to acknowledge Helena Daudt, PhD and Roseanne Beauthin,RN, PhD, who conceptualized, supported and championed this project from its outset.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no existing or perceived conflicts of interest in relation to this project.

References

- Brighton LJ, Koffman J, Hawkins A, McDonald C, O’Brien S, et al. (2017) A Systematic Review of End-of-Life Care Communication Skills Training for Generalist Palliative Care Providers: Research Quality and Reporting Guidance. J Pain Symptom Manage 54: 417-425.

- Lippe M, Johnson B, Mohr SB, Kraemer KR (2018) Palliative Care Educational Interventions for Prelicensure Health-Care Students: An Integrative Review. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 35: 1235-1244.

- Collingridge Moore D, Payne S, Van den Block L, Ling J, Froggatt K, et al. (2020) Strategies for the implementation of palliative care education and organizational interventions in long-term care facilities: A scoping review. Palliat Med 34: 558-570.

- Health Canada (2021) Third annual report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada 2021.

- Wiebe E, Green S, Wiebe K (2021) Medical assistance in dying (MAiD) in Canada: practical aspects for healthcare teams. Ann Palliat Med 10: 3586-3593.

- Wong A, Hsu AT, Tanuseputro P (2019) Assessing attitudes towards medical assisted dying in Canadian family medicine residents: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Ethics 20: 103.

- Antonacci R, Baxter S, Henderson JD, Mirza RM, Klinger CA (2021) Hospice Palliative Care (HPC) and Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD): Results From a Canada-Wide Survey. J Palliat Care 36: 151-156.

- Wales J, Isenberg SR, Wegier P, Shapiro J, Cellarius V, et al. (2018) Providing Medical Assistance in Dying within a Home Palliative Care Program in Toronto, Canada: An Observational Study of the First Year of Experience. J Palliat Med 21: 1573-1579.

- Whitley Bell K (2012) In a Language Spoken and Unspoken: Nurturing Our Practice as Humanistic Clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage 43: 973-979.

- Hui D, Nooruddin Z, Didwaniya N, Dev R, De La Cruz M, et al. (2014) Concepts and Definitions for “Actively Dying,” “End of Life,” “Terminally Ill,” “Terminal Care,” and “Transition of Care”: A Systematic Review. J Pain Symptom Manage 47: 77-89.

- Hui D, Zhukovsky DS, Bruera E (2018) Serious Illness Conversations: Paving the Road with Metaphors. Oncologist 23: 730-733.

- Stanek S (2017) Goals of care: a concept clarification. J Adv Nurs 73: 1302-1314.

- Black K (2007) Advance Care Planning Throughout the End-of-Life: Focusing the Lens for Social Work Practice. J Soc Work End-of-Life Palliat Care 3: 39-58.

- Maguire P (1998) Breaking bad news. Eur J Surg Oncol 24: 188-191.

- Sullivan SS, Ferreira da Rosa Silva C, Meeker MA (2015) Family Meetings at End of Life: A Systematic Review. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 17: 196-205.

- Herbert CP (2005) Changing the culture: Interprofessional education for collaborative patient-centred practice in Canada. J Interprof Care 19: 1-4.

- Van Hecke A, Duprez V, Pype P, Beeckman D, Verhaeghe S (2020) Criteria for describing and evaluating training interventions in healthcare professions-CRe-DEPTH. Nurse Educ Today 84: 4254.

- Samala RV, Hoeksema LJ, Colbert CY (2019) A Qualitative Study of Independent Home Visits by Hospice Fellows: Addressing Gaps in ACGME Milestones by Fostering Reflection and Self-Assessment. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 36: 885-892.

- Isaacson MJ, Minton ME (2018) End-of-Life Communication: Nurses Cocreating the Closing Composition with Patients and Families. Adv Nurs Sci 41: 2-17.

- Beattie J, Brady L, Tobias T (2014) Improving Clinician Confidence and Skills: Piloting a Web-Based Learning Program for Clinicians in Supportive Care Screening of Cancer Patients. J Cancer Educ 29: 38-43.

- Erickson JM, Blackhall L, Brashers V, Varhegyi N (2015) An Interprofessional Workshop for Students to Improve Communication and Collaboration Skills in End-of-life Care. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 32: 876-880.

- Bunting M, Cagle JG (2016) Impact of brief communication training among hospital social workers. Soc Work Health Care 55: 794-805.

- Efstathiou N, Walker WM (2014) Interprofessional, simulation-based training in end of life care communication: a pilot study. J Interprof Care 28: 68-70.

- Mehta AK, Wilks S, Cheng MJ, Baker K, Berger A (2018) Nurses’ Interest in Independently Initiating End-of-Life Conversations and Palliative Care Consultations in a Suburban, Community Hospital. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 35: 398-403.

- Wittenberg E, Ferrell B, Goldsmith J, Ragan SL, Buller H (2018) COMFORTTMSM communication for oncology nurses: Program overview and preliminary evaluation of a nationwide train-the-trainer course. Patient Educ Couns 101: 467-474.

- Nan JKM, Lau BH-P, Szeto MML, Lam KKF, Man JCN, et al. (2018) Competence Enhancement Program of Expressive Arts in End-of-Life Care for Health and Social Care Professionals: A Mixed-Method Evaluation. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 35: 1207-1214.

- Selman LE, Brighton LJ, Hawkins A, McDonald C, O’Brien S, et al. (2017) The Effect of Communication Skills Training for Generalist Palliative Care Providers on Patient-Reported Outcomes and Clinician Behaviors: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage 54: 404-416.

- Harwell JH (2019) Integration of end of life concepts into the curriculum of an Associate of Science in nursing program. University of Alabama Libraries.

- Levine S, O’Mahony S, Baron A, Ansari A, Deamant C, et al. (2017) Training the Workforce: Description of a Longitudinal Interdisciplinary Education and Mentoring Program in Palliative Care. J Pain Symptom Manage 53: 728-737.

- Buller H, Virani R, Malloy P, Paice J (2019) End-of-Life Nursing and Education Consortium Communication Curriculum for Nurses. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 21: 5-12.

- Chappell P, Lee S, Ross J, Healy J, Sanchez-Reilly S (2014) Communicating with Dying Patients and Their Families: Multimedia Training in End-of-Life Care (SA522-C). J Pain Symptom Manage 47: 460-461.

- Von Gunten CF, Mullan PB, Nelesen R, Garman K, McNeal H, et al. (2017) Primary Care Residents Improve Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes, and Practice After a Clinical Curriculum With a Hospice. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 34: 713-720.

- Pollak KI, Gao X, Beliveau J, Griffith B, Kennedy D, et al. (2019) Pilot Study to Improve Goals of Care Conversations Among Hospitalists. J Pain Symptom Manage 58: 864-870.

- Johnson LA, Gorman C, Morse R, Firth M, Rushbrooke S (2013) Does communication skills training make a difference to patients’ experiences of consultations in oncology and palliative care services?: Communication skills training. Eur J Cancer Care 22: 202-209.

- Nussbaum SE, Oyola S, Egan M, Baron A, Wackman S, et al. (2019) Incorporating Older Adults as “Trained Patients” to Teach Advance Care Planning to Third-Year Medical Students. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 36: 608-615.

- Sharma RK, Cameron KA, Zech JM, Jones SF, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA (2019) Goals-of-Care Decisions by Hospitalized Patients With Advanced Cancer: Missed Clinician Opportunities for Facilitating Shared Decision-Making. J Pain Symptom Manage 58: 216-223.

- Pollak KI, Gao X, Arnold RM, Arnett K, Felton S, Fairclough DL, et al. (2020) Feasibility of Using Communication Coaching to Teach Palliative Care Clinicians Motivational Interviewing. J Pain Symptom Manage 59: 787-793.

- Chen Y, Whearty L, Winstanley D, Fourie D, Rose M, et al. (2020) Junior doctors’ experience of interprofessional shadowing in a palliative care setting. J Interprof Care 34: 276-278.

- Sagha Zadeh R, Eshelman P, Setla J, Sadatsafavi H (2018) Strategies to Improve Quality of Life at the End of Life: Interdisciplinary Team Perspectives. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 35: 411-416.

- Schillerstrom JE, Sanchez-Reilly S, O’Donnell L (2012) Improving Student Comfort with Death and Dying Discussions Through Facilitated Family Encounters. Acad Psychiatry 36: 188.

- McGinley JM, Waldrop DP (2020) Navigating the Transition from Advanced Illness to Bereavement: How Provider Communication Informs Family-related Roles and Needs. J Soc Work End-of-Life Palliat Care 16: 175-198.

- Chan B. An Evaluation of the Influence of the Care (Compassion and Respect at the End-of-Life) Program on Registered Nurses’ Knowledge and Comfort About End-of-Life Care and Care Delivery for Patients with Life-Limiting Illnesses. Azusa Pacific University.

- Martin M (2019) Breaking Bad News: Providing Communication Guidance to Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) Students. The University of Arizona.

- Oh C, Miller-Lewis L, Tieman J (2020) Participation in an Online Course about Death and Dying: Exploring Enrolment Motivations and Learning Goals of Health Care Workers. Educ Sci 10: 112.

- Starks H, Coats H, Paganelli T, Mauksch L, van Schaik E, et al. (2018) Pilot Study of an Interprofessional Palliative Care Curriculum: Course Content and Participant-Reported Learning Gains. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 35: 390-397.

- Lum HD, Dukes J, Church S, Abbott J, Youngwerth JM (2018) Teaching Medical Students About “The Conversation”: An Interactive Value-Based Advance Care Planning Session. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 35: 324-329.

- Fletcher TE (2012) An Educational Intervention for Hospice and Palliative Care Nurses.

- Taylor KE (2019) Facilitating End-of-life Care Discussions in the Emergency Department. The University of Arizona.

- Head BA, Schapmire T, Hermann C, Earnshaw L, Faul A, et al. (2014) The Interdisciplinary Curriculum for Oncology Palliative Care Education (iCOPE): Meeting the Challenge of Interprofessional Education. J Palliat Med 17: 1107-1114.

- Paladino J, Kilpatrick L, O’Connor N, Prabhakar R, Kennedy A, et al. (2020) Training Clinicians in Serious Illness Communication Using a Structured Guide: Evaluation of a Training Program in Three Health Systems. J Palliat Med 23: 337-345.

- Mott ML, Gorawara-Bhat R, Marschke M, Levine S (2014) Medical Students as Hospice Volunteers: Reflections on an Early Experiential Training Program in End-of-Life Care Education. J Palliat Med 17: 696-700.

- Tuffrey-Wijne I (2013) A new model for breaking bad news to people with intellectual disabilities. Palliat Med 27: 5-12.

- Kelley LT, Coderre-Ball AM, Dalgarno N, McKeown S, Egan R (2020) Continuing Professional Development for Primary Care Providers in Palliative and End-of-Life Care: A Systematic Review. J Palliat Med 23: 1104-1124.

- Gewarges M, Gencher J, Rodin G, Abdullah N (2020) Medical Assistance in Dying: A Point of Care Educational Framework For Attending Physicians. Teach Learn Med 32: 231-237.

- LeBlanc S, MacDonald S, Martin M, Dalgarno N, Schultz K (2022) Development of learning objectives for a medical assistance in dying curriculum for Family Medicine Residency. BMC Med Educ 22: 167.

- Li M, Watt S, Escaf M, Gardam M, Heesters A, et al. (2017) Medical Assistance in Dying -Implementing a Hospital-Based Program in Canada. N Engl J Med 376: 2082-2088.

- Post SG, Ng LE, Fischel JE, Bennett M, Bily L, et al. (2014) Routine, empathic and compassionate patient care: definitions, development, obstacles, education and beneficiaries: Empathy and compassionate patient care. J Eval Clin Pract 20: 872-880.

- Brighton LJ, Selman LE, Bristowe K, Edwards B, Koffman J, et al. (2019) Emotional labour in palliative and end-of-life care communication: A qualitative study with generalist palliative care providers. Patient Educ Couns 102: 494-502.

- McCabe MRP, Goldhammer D, Mellor D, Hallford D, Davison T (2012) Evaluation of a training program to assist care staff to better recognize and manage depression among palliative care patients and their families. J Palliat Care 28: 75-82.

- McConigley R, Aoun S, Kristjanson L, Colyer S, Deas K, et al. (2012) Implementation and evaluation of an education program to guide palliative care for people with motor neurone disease. Palliat Med 26: 994-1000.

- Slort W, Blankenstein AH, Schweitzer BPM, Deliens L, van der Horst HE (2014) Effectiveness of the ‘availability, current issues and anticipation’ (ACA) training programme for general practice trainees on communication with palliative care patients: A controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 95: 83-90.

- Hamayoshi M, Goto S, Matsuoka C, Kono A, Miwa K, et al. (2019) Effects of an advance care planning educational programme intervention on the end-of-life care attitudes of multidisciplinary practitioners at an acute hospital: A pre- and post-study. Palliat Med 33: 1158-1165.

- Kelley AS, Back AL, Arnold RM, Goldberg GR, Lim BB, et al. (2012) Geritalk: Communication Skills Training for Geriatric and Palliative Medicine Fellows. J Am Geriatr Soc 60: 332-337.

- Wechter E, O’Gorman DC, Singh MK, Spanos P, Daly BJ (2015) The Effects of an Early Observational Experience on Medical Students’ Attitudes Toward End-of-Life Care. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 32: 52-60.

- Graham R, Lepage C, Boitor M, Petizian S, Fillion L, et al. (2018) Acceptability and feasibility of an interprofessional end-of-life/palliative care educational intervention in the intensive care unit: A mixed-methods study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 48: 75-84.

- Neuderth S, Lukasczik M, Thierolf A, Wolf H-D, van Oorschot B, et al. (2019) Use of standardized client simulations in an interprofessional teaching concept for social work and medical students: first results of a pilot study. Soc Work Educ 38: 75-88.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Citation: Trouton K, Vaitekonyte J, Clark B (2023) Evaluating End-of-life andMedical Assistance in Dying Communication Learning - A Literature Review. JPalliat Care Med 13: 501. DOI: 10.4172/2165-7386.1000501

Copyright: © 2023 Trouton K, et al. This is an open-access article distributed underthe terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricteduse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author andsource are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Conferences

42nd Global Conference on Nursing Care & Patient Safety

Toronto, CanadaRecommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 2264

- [From(publication date): 0-2023 - Mar 12, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 2049

- PDF downloads: 215