Ethnobotany of Medicinal Plants Used to Treat Leishmaniasis in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review

Received: 21-Feb-2018 / Accepted Date: 06-Mar-2018 / Published Date: 12-Mar-2018 DOI: 10.4172/2573-4555.1000271

Abstract

Background: Leishmaniasis is an infectious tropical vector born disease imposing high burden in developing countries including Ethiopia. Its treatment is still using pentavalent antimonial which have been used for several years and prone to drug resistance. Other alternative drugs like amphotericin B also have horrible side effects. Therefore, new drugs are urgently needed and drug screening efforts should be encouraged. No review has been done that broadly indicates medicinal plants used to treat leishmaniasis. The aim of this review was to provide an overview of the Ethnobotany of medicinal plants used to treat leishmaniasis in Ethiopia.

Materials and methods: Databases (Pub Med, Google Scholar, Research Gate, and Hinari) were searched for published articles on the Ethnobotany of medicinal plants used to treat leishmaniasis in Ethiopia without restriction in the year of publication or methodology. Some studies were also identified with manual Google search. Primary search terms were “Leishmania review”, “Leishmaniasis” “Ethiopia”, “medicinal plants” and “Ethnobotany”. Studies that did not contain full ethnobotanical data on to medicinal plants traditionally used to treat Leishmaniasis and plants which are out of flora list of Ethiopia were excluded from this review.

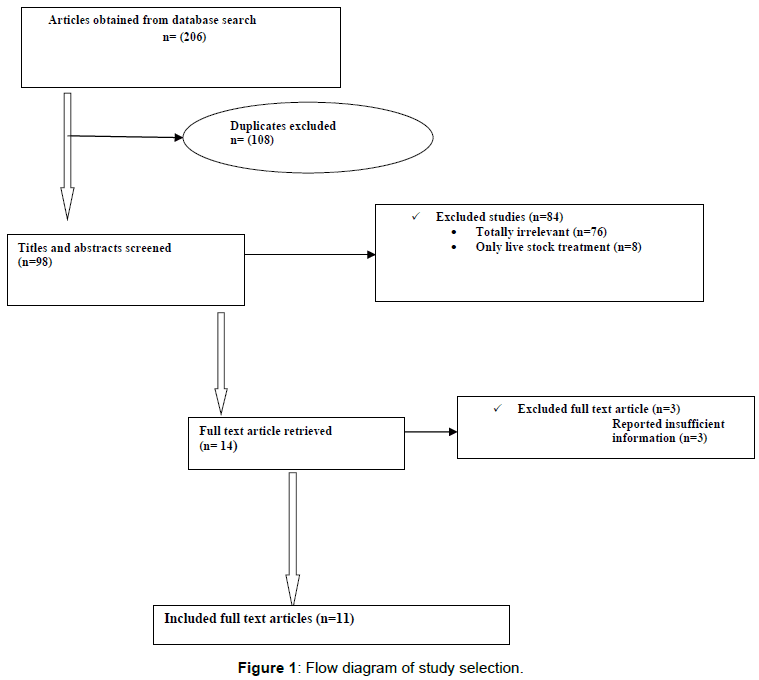

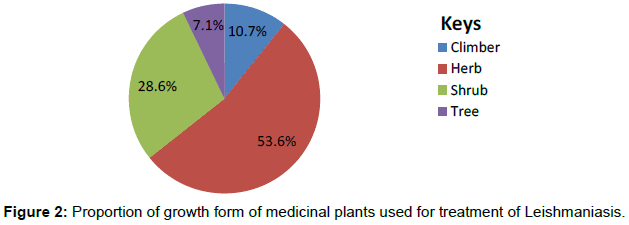

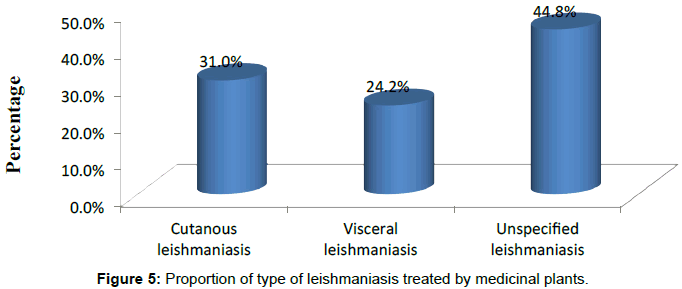

Results: The database search produced a total of 206 articles. After adjustment for duplicates and inclusion and exclusion criteria, 11 articles were found appropriate for the review. Majority o the studies were qualitative in nature and some were mixed type. None of the medicinal plants traditionally used to treat leishmaniasis in Ethiopia are confirmed scientifically. Of the 28 plants identified from the various studies, 53.6% were herbs and the common plant part used was leaf (44.8%) followed by latex (20.7%). Majority of the plant remedies were given topically (75.7%). Cutaneous leishmaniasis comprises high percentage of leishmania infection treated by traditional medicinal plants.

Conclusion: Varity of medicinal plants have been used by Ethiopian people of different cultures to treat leishmaniasis. Most of the plants were herbs and the commonly used plant part was leaf. Majority of prepared remedies were applied externally to the affected part. There is an urgent need to conduct clinical trials on such plants to support traditional claims and to analyze molecular and cellular mechanisms involved.

Keywords: Ethnobotany; Leishmaniasis; Medicinal plants; Review; Ethiopia

Introduction

Leishmaniasis is a tropical disease caused by protozoan parasites of the genus leishmania [1]. It is one of neglected disease and even not include in the list of tropical disease priorities in Ethiopia [2]. Leishmaniasis has a focal distribution and it is common to remote areas like other neglected tropical disease [3]. Visceral leishmaniasis specially is recognized as serious public health problem as it causes death if left untreated having high case fatality rate [4]. Lack of simple and easily applied tools for its management and complex ecoepidemiology contribute for the difficulty in prevention and control of the disease [3,5].

Plants remain to be the source for majority of people in developing countries to treat various health problems [6]. They are a rich source of many natural products most of which have been extensively used for human welfare, and treatment of various diseases [7,8]. In Ethiopia a variety of medicinal plants are used as natural medicines without scientific base. Plant extracts or plant derived compounds provide important source of new medicinal agents [9,10]. A high diversity of secondary metabolites with interesting biological activities can be produced from plant extracts [11].

About eighty (80%) percent of the Ethiopia people and ninety percent (90% ) of livestock depend on traditional medicine for their health care and more than 95 percent of traditional medicine preparations are made from plant origin. Similarly, there has been a continuous growth of demand for traditional medicines globally and in many developing countries health care system [12]. Urgent need for alternative drug formulation leads to screening of natural products for potential use in leishmaniasis treatment.

Different studies have been conducted on Ethnobotany of medicinal plants used to treat various human diseases in different parts of Ethiopia. However, there has not been any review conducted on Ethnobotany of plants used to treat Leishmaniasis. Therefore, there is an urgent need to assess the overall traditional preparation techniques and types of plants used in the management of leishmaniasis. This review is complementary of various medicinal plants that have been directed towards plants having leishmanicidal activity. It gives a comprehensive information on the scientific name of plants, method of preparation, route of administration, plant part used and the habit of the plant used. This review will also give new force for obtaining synthetic compounds.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

Databases (Pub Med, Google Scholar, Research Gate, and Hinari) were searched for published studies done on Ethnobotany of medicinal plants in Ethiopia. Some studies were also identified with a manual Google search. No restriction was applied to the year of publication, methodology, or study subjects. Primary search terms were “Leishmania review”, “Leishmaniasis,” “Ethiopia”, “medicinal plants”, and “Ethnobotany”.

Inclusion/exclusion criterion

Studies which do not contain full information about Ethnobotany (method of preparation, growth form, plant part used, route of administration), surveys which did not address intestinal parasitosis as a disease treated traditionally by practitioners and studies which incorporated only medicinal plants of livestock usage were excluded. Plants which are out of flora list of Ethiopia were also excluded from this review [13].

Data abstraction

The authors screened the articles based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria. The details of medicinal plants were extracted from each study using an abstraction forms: scientific, family and local name, growth form of plant, plant part used, methods of preparation, specific use and route of administration (Table 1).

| S. no | Scientific name | Family name | Local name | Growth form | PU | Specific use | Method of preparation | RoA | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Euphorbia abyssinica Gmel | Euphorbiaceae | Kulkual (Am) | Tree | leaf | Cutaneous leishmaniasis | Crushing the leaf and mixing it with butter | Topical | [15] |

| Latex | Visceral leishmaniasis | The wound is touched with a hot thread and the latex of 1 and 2 is applied on the wound | Topical | [16] | |||||

| 2 | Englerinawoodfordioides (Schweinf.) M. Gilbert | Loranthaceae | Teketsila (Am) | Shrub | Leaf | Cutaneous leishmaniasis | Crushing the leaf and apply it topically | Topical | [15] |

| 3 | BruceaantidysentericaJ. F. Mill. | Simaroubaceae | Abalo (Am) | Shrub | Seed | Cutaneous leishmaniasis | Crushing the seed and apply on the infected area | Topical | |

| 4 | Daturastramonium L. | Solanaceae | Mestenager (Tig) | Herb | Leaf | Unspecified Leishmaniasis | Leaves are crushed and pasted on affected area | Topical | [17] |

| 5 | Euphorbia cactus Boiss | Euphorbiaceae | Kolqualhamat (Tig) | Shrub | Latex | Unspecified Leishmaniasis | Latex is smeared on affected area | Topical | |

| 6 | Euphorbia petitianaA. Rich. | Euphorbiaceae | Hindukduk (Tig) | Herb | Latex | Unspecified Leishmaniasis | Rub leaf on affected part until cure | Topical | [18] |

| 7 | Argemonemexicana L. | Papaveraceae | Eshoktilian, medafe(Tig) |

Herb | Latex | Unspecified Leishmaniasis | Apply it on affected part until cure | Topical | |

| 8 | Asparagus africanus Lam. | Asparagaceae | Kastanito(Tig) | Climber | Root | Unspecified Leishmaniasis | Crush, mix it with honey and apply on affected part | Topical | |

| 9 | Commicarpuspedunculosus (A. Rich.) Cufod. |

Nyctaginaceae | Eznianchiwa (Tig) | Herb | Leaf | Unspecified Leishmaniasis | Crush, boil with butter and apply it on affected part | Topical | |

| 10 | Phytolacca dodecandra L. Herit. |

Phytolaccaceae | Endode (Or) | Shrub | Root | Cutaneous leishmaniasis |

The root is powdered and pasted with butter. | Topical | [19] |

| 11 | Gossypium spp. | Malvaceae | Jirbi (Or) Tit(A) | Shrub | Seed | Cutaneous leishmaniasis |

The seed is powdered and pasted with butter | Topical | |

| 12 | Nicandraphysalodes (L.) Gaertn. |

Solanaceae | Machara(Or) | Herb | Leaf | Unspecified Leishmaniasis | Powdered leaf is mixed with water and drunk | Oral | [20] |

| 13 | Plectranthusspp. | Lamiaceae | Dachet(Am) | Herb | Leaf | Unspecified Leishmaniasis | Crush paste | Topical | [21] |

| 14 | Clematis hirsute Perr & Guill | Ranunculaceae | AzoHareg (Am) | Climber | Leaf | Unspecified Leishmaniasis | Mildly heated Powder paste | Topical | |

| 15 | Guizotiaabyssinica (L. F.) Cass. | Astraceae | Noug (Am) | Herb | Seed | Unspecified Leishmaniasis | Mildly heated Powder paste | Topical | |

| 16 | Hordeumvulgare L. | Poaceae | Gebis (Am) | Herb | Seed | Visceral leishmaniasis | Barely dough (Ligus) is prepared; bread is baked from this Ligus and applied on the wound as bandage with the hot inner soft part. | Bandaging/Dressing | [16] |

| 17 | Ficusvasta forssk. | Moraceae | Shola (Am) | Tree | Latex | Visceral leishmaniasis | The latex is applied on the wound till it is cured. | Topical | |

| 18 | Clematis hirsute Perr and Guill | Ranunculaceae | Yeazo Areg (Am) | Climber | Latex | Visceral leishmaniasis | The wound is touched with a hot thread and the latex of 1 and 2 is applied on the wound | Topical | |

| 19 | Rehamnusprinoides L. Herit, | Rhamnaceae | Gesho (Am) | Shrub | Leaf | Visceral leishmaniasis | The leaves are crushed into powder and applied as bandage on the wound. | Bandaging/ Dressing | |

| 20 | Rumex abyssinicus Jacq | Polygonaceae | Mekmeko (Am) | Herb | Root | Visceral leishmaniasis | The roots are crushed and applied bandage on the wound. | Bandaging/ Dressing | |

| 21 | Ranunculus mulifidus Forssk. | Ranunculaceae | Etsesyol (Am) | Herb | Leaf | Visceral leishmaniasis | The leaves are pounded to powder and mixed with honey (to attach) and applied on the wound | Topical | |

| 22 | Scadoxusmultiflorus (Martyn) Raf | Amaryllidaceae | Dem Astefi (Am) | Herb | Root | Unspecified Leishmaniasis | Root paste is applied topically | Topical | [22] |

| 23 | RumexnepalensisSpreng. | Polygonaceae | Tult (Am) | Herb | Root | Unspecified Leishmaniasis | Rubbing the spot with fresh root and leaf until cure; topical | Topical | |

| 24 | Dissotissenegambiensis (Guill. &Perr.) Triana | Melastomataceae | NM | Herb | Leaf | Cutaneous leishmaniasis | NM | Nasal | [23] |

| 25 | Ocimumlamiifolium Hochst. Ex Benth. |

Lamiaceae | NM | Herb | Leaf | Cutaneous leishmaniasis | NM | Nasal | |

| 26 | Sphearanthus Steetzii Oliv. & Hiern |

Asteraceae | Qoricha –Cheffe (Or) | Shrub | Bark & Leaf |

Cutaneous leishmaniasis |

Leaves and bark are pounded while fresh and the concoction applied on the skin surface where wounds occur | Bandaging/ Dressing | [24] |

| 27 | Clematis simensisFresen. | Ranunculaceae | Hazo (T) | Herb | Leaf | Cutaneous leishmaniasis |

Mixed with Sidaschimpri, crushed and placed on the infected site | Topical | [18] |

| 28 | Osyris quadripartite Decn | Santalaceae | Qerets (Am) | Shrub | Leaf | Unspecified Leishmaniasis | NM | Topical | [25] |

Table 1: Ethnobotany of medicinal plants used to treat Leishmaniasis (Am= Amharic, Or=Oromifa, A=Ari, Tig=Tigre, PU=Parts used, RoA=Route of administration, NM=not mentioned).

Results

Literature search results

The search of the Pub Med, Google Scholar, Research Gate, and Hinari databases and Google provided a total of 206 studies. After adjustment for duplicates, 98 remained. Of these, 84 studies were discarded, since after review of their titles and abstracts, they did not meet the criteria. The full texts of the 14 studies were reviewed in detail. Three studies were discarded after the full text had been reviewed, since they did not address much of the required information. Finally, 11 studies were included in the review (Figure 1).

Study characteristics

Methodological validity of all the 11 studies was checked prior to inclusion in the review by undertaking critical appraisal using a standardized instrument adapted to Guyatt et al. [14]. The 11 studies differed significantly in the number of plants identified. From these 11 articles, the majority (9) were conducted to assess the Ethnobotany of medicinal plants used to treat human diseases, while the rest studies focused on Ethnobotany of medicinal plants used in the treatment of both human and livestock disorders. All the studies were conducted in different parts of Ethiopia and are qualitative and mixed type. The studies used purposive sampling to select study subjects. The detailed description of each plant collected from different studies is given below (Table 1).

Medicinal plants growth form and plant parts used

Twenty eight medicinal plants distributed in 19 families were identified from the reviewed studies. Unfortunately, none of the medicinal plants traditionally used to treat leishmaniasis in Ethiopia are proofed scientifically. Majority of the plants were herbs (53.6%) followed by shrubs (28.6%) (Figure 2). The commonly used plant parts were leaves (44.8 %) followed by latex (20.7%). Root account 17.2% of the total plant parts used (Figure 3).

Method of preparation and route of administration

Traditional medicinal practitioners in Ethiopia apply different techniques of preparation like drying, crushing, concoction, and decoction (Table 1). They use simple methods and equipments during their remedy preparation. Of the routes commonly used to administer remedies in the treatment of leishmaniasis, topical route was the common route which consists 75.7% (n=22) followed by bandaging 13.8% (n=4) and nasal 6.9% (n=2) way of administration. Only one preparation was intended to be administered orally (Figure 4).

Type of leishmaniasis treated with medicinal plants

Cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis were identified to be leishmania infections that can be treated traditionally when encountered in human by using medicinal plants listed in the table. They account 31.0% and 24.2% respectively. The remaining 44.8% of leishmania infections were not specified and can be also treated by traditional healers using different medicinal plants (Figure 5).

Discussion

This review revealed that about 28 plant species find applications by the traditional healers of the country to treat leishmaniasis. These plants were distributed in 19 families and none of them was confirmed scientifically in animal model. This indicates less attention is given to the traditional medicine practices in drug formulation in general. This review revealed the presence of high species diversity of medicinal plants used for treatment of leishmaniasis. This is due to the climatic variation that exists in different provinces of Ethiopia. Family Ranunculaceae accounts the highest percentage (21.0%) followed by family Euphorbiaceae (15.8%). Family Astraceae and Solanaceae account 10.5% each. Another study undertaken in Spain [26] and Korea [27] revealed that Asteraceae has the highest number of medicinal plants. According to a study in Nigeria [28] family Caesalpiniaceae has higher number of plants.

According to this review, herbs constitute the highest percentage of the plants identified to have medicinal value in the treatment of leishmaniasis followed by shrubs. Similarly, other studies conducted elsewhere in Ethiopia indicated the dominance of herbs [29-34]. Herbs are seasonal which indicates that they are not accessible throughout the year which needs storage but can be easily cultivated in a limited area. However, Shrubs are known to be non-seasonal in nature which implies that they are accessible throughout a year and no need to store. In this review, leaf was the most commonly used plant part in the preparation of remedies as compared to other parts. Studies conducted in Nigeria [28] and Israel [35] also showed the dominance of leaves in the preparation of remedies. However, the use of plants leaf for medicinal purposes has its own limitations unless the plant is evergreen. Because leaves are seasonal this implies that they are not available throughout a year which needs storage if non-fresh leaves are required. There is no threat to the mother plant when leaves are harvested for medicinal purpose instead the highest threat to the mother plant comes with root, bark and stem harvest.

Medicinal plants were formulated in various forms using different solvents and additives. Traditional medicinal Practitioners prepare remedies in such a simple manner without need of advanced techniques and further processing. This may be due to lack of formal education and processing instruments. Practitioners used butter, porridge, sugar, and honey as additives to increase the medicinal value/potency of the remedies. This is agreed with a study conducted in Israel [35] and Hawassa [36].

This review also revealed that high proportions of remedies were given topically. The reason for this is, traditional medicinal practitioners prefer simple routes like topical and oral that do not require special skill due to lack of ability to administer remedies in other complex routes like intravenous and intramuscular. As leishmania parasite is found in the affected area and medicines are applied to the affected area, topical routes allow rapid interaction between the prepared medicines and the parasite increasing its potency. Another study conducted in Sheko ethnic group of Southwest Ethiopia revealed that the most medicinal plant preparations were administered cutaneously [37].

Even though unspecified Leishmania infections were reported, in this review cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis were the common Leishmania infections that can be treated traditionally when encountered in human using medicinal plants. The mechanism of action of Plant extracts and isolated secondary metabolites like flavonoids is often by interfering with central targets of Leishmania parasites (intercalation with DNA, alkylation of DNA), membrane integrity, microtubules and neuronal signal transduction [11].

Conclusion

In the present review, a total of twenty eight medicinal plants have been identified and recorded for their use for the treatment of leishmaniasis in Ethiopia. Most of the plants were herbs and the commonly used plant part was leaf. Even though most of these medicinal plants are widely utilized in different provinces of Ethiopia, information on their safety and efficacy are not scientifically proofed by using animal models. Therefore, it is advisable for researchers to conduct the safety and efficacy studies of the traditionally claimed medicinal plants in more detail in animal models and if possible in clinical trials.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for Publication

Not applicable

Availability of Data and Material

No additional data are required; all information is clearly stated in the main manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that there is no competing interest.

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Authors’ Contribution

MW, YA conceive the review, YA involved in data extraction, data analysis, interpretation and drafting of the manuscript. HR involved in data analysis and quality assessment. MW Critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgment

Not applicable

References

- Grimaldi G, Tesh R (1993) Leishmaniasis of the New World: current concepts and implications for future research. Clin Microbiol Rev 6: 230-250.

- Hotez PJ, Remme JH, Buss P, George G, Morel C, et al. (2004) Combating tropical infectious diseases: report of the Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries Project. Clin Infect Dis 6: 871-878

- Bern C, Maguire JH, Alvar J (2008) Complexities of assessing the disease burden attributable to leishmaniasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10: e313

- Bern C, Hightower AW, Chowdhury R, Ali M, Amann J, et al. (2005) Risk factors for kala-azar in Bangladesh. Emerg Infect Dis 5: 655

- Alvar J, Yactayo S, Bern C (2006) Leishmaniasis and poverty. Trends Parasitol 12: 552-557.

- Birhanu A, Haji F (2017) Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal Plants Used for the Treatment of Human and Livestock Ailments in Dawe Kachen District of Bale Zone, Southeast Ethiopia. Int J Emerg Trends Sci Technol 4: 5043-5055

- Birhanu Z, Endale A, Shewamene Z (2015) An ethnomedicinal investigation of plants used by traditional healers of Gondar town, North-Western Ethiopia. J Med Plant Res 2: 36-43

- Karunamoorthi K, Jegajeevanram K, Vijayalakshmi J, Mengistie E (2013) Traditional medicinal plants: a source of phytotherapeutic modality in resource-constrained health care settings. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med 1: 67-74

- De Carvalho PB, Ferreira EI (2001) Leishmaniasis phytotherapy. Nature's leadership against an ancient disease. Fitoterapia 6: 599-618

- Kayser O, Kiderlen AF (2001) In vitro leishmanicidal activity of naturally occurring chalcones. Phytother Res 2: 148-52

- Wink M (2012) Medicinal plants: a source of anti-parasitic secondary metabolites. Molecules 11: 12771-91

- Fentahun Y, Eshetu G, Worku A, Abdella T (2017) A survey on medicinal plants used by traditional healers in Harari regional State, East Ethiopia. J Med Plant Res1: 85-90

- Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea. Edited by Hedberg I, Edwards S. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Uppsala, Sweden: Uppsala University; 2009: Vol. 8.

- Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Cook DJ (1994) Users’ guides to the medical literature II: how to use an article about therapy or prevention. JAMA 1: 59-63

- Wubetu M, Abula T, Dejenu G (2017) Ethnopharmacologic survey of medicinal plants used to treat human diseases by traditional medical practitioners in Dega Damot district, Amhara, Northwestern Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes 1: 157

- Limenih Y, Umer S, Wolde-Mariam M (2015) Ethnobotanical study on traditional medicinal plants in Dega damot woreda, Amhara region, North Ethiopia. Inter J Res Pharm Chem 5: 258-73

- Araya S, Abera B, Giday M (2015) Study of plants traditionally used in public and animal health management in Seharti Samre District, Southern Tigray, Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 11: 22.

- Teklay A, Abera B, Giday M (2013) An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used in Kilte Awulaelo District, Tigray Region of Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 1: 65

- Suleman S, Alemu T (2012) A survey on utilization of ethnomedicinal plants in Nekemte town, East Wellega (Oromia), Ethiopia. J Herbs Spices Med Plants 1: 34-57

- Mesfin F, Seta T, Assefa A (2014) An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Amaro woreda, Ethiopia.

- Teklehaymanot T, Giday M, Medhin G, Mekonnen Y (2007) Knowledge and use of medicinal plants by people around Debre Libanos monastery in Ethiopia. J Ethnopharmacol 2: 271-83

- Teklehaymanot T (2009) Ethnobotanical study of knowledge and medicinal plants use by the people in Dek Island in Ethiopia. J Ethnopharmacol 1: 69-78

- Giday M, Asfaw Z, Woldu Z (2009) Medicinal plants of the Meinit ethnic group of Ethiopia: an ethnobotanical study. J Ethnopharmacol 3: 513-21

- Tadesse M, Hunde D, Getachew Y (2005) Survey of medicinal plants used to treat human diseases in Seka Chekorsa, Jimma Zone, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci 2

- Giday M, Teklehaymanot T, Animut A, Mekonnen Y (2007) Medicinal plants of the Shinasha, Agew-awi and Amhara peoples in northwest Ethiopia. J Ethnopharmacol 3: 516-25

- Gorka M (2013) Medicinal plants traditionally used in the northwest Spain. J Ethnopharmacol 4: 01-22.

- Mi-Jang S (2013) Ethno pharmacological survey of medicinal plants in Jeju Island, Korea. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 9: 48.

- Abubakar M, Musab A, Ahmeda M (2007) The perception and practice of traditional medicine in the treatment of cancers and inflammations by the Hausa and Fulani tribes of Northern Nigeria. J Ethnopharmacol 111: 625-629

- Eshete A, Kelbessa E, Dalle G (2016) Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Guji Agro-pastoralists, Blue Hora District of Borana Zone, Oromia Region, Ethiopia. J Med Plants Stud 4: 170-84

- Seifu T (2004) Ethnobotanical and ethno pharmaceutical studies on medicinal plants of Chifra district, Afar region, North Eastern Ethiopia.

- Hareya F (2003) Local Health Knowledge and Home-Based Medicinal Plant Use in Ethiopia. International Development Centre: Ph. D. Dissertation, Oxford University, Oxford.

- Amsalu N (2010) An Ethnobotanical Study of Medicinal plants in Farta Woreda, South Gondar Zone of Amhara Region, Ethiopia. Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa.

- Behailu E (2010) Ethnobotanical study of traditional medicinal plants of Goma Woreda, Jima zone of Oromia region, Ethiopia.

- Agisho H, Osie M, Lambore T (2014) Traditional medicinal plants utilization, management and threats in Hadiya Zone, Ethiopia. J Med Plant Res 2.

- Said O (2002) Ethno pharmacological survey of medicinal herbs in Israel, the Golan Heights and the West Bank region. J Ethnopharmacol 3: 251-265

- Reta R (2013) Assessment of indigenous knowledge of medicinal plant practice and mode of service delivery in Hawassa city, southern Ethiopia. J Med Plant Res 9: 517-535.

- Mirutse G, Zemede A, Zerihun W (2010) Ethnomedicinal study of plants used by Sheko ethnic group of Ethiopia. J Ethnopharmacol 132: 75-85.

Citation: Aschale Y, Wubetu M, Reta H (2018) Ethnobotany of Medicinal Plants Used to Treat Leishmaniasis in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review. J Tradit Med Clin Natur 7: 271. DOI: 10.4172/2573-4555.1000271

Copyright: © 2018 Aschale Y, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 7634

- [From(publication date): 0-2018 - Jan 15, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 6646

- PDF downloads: 988