Epidemiological Distribution and Potential Risk Factors of Orientia Tshushugamushi Infection in Eastern Uttar Pradesh, India

Received: 15-Sep-2020 / Accepted Date: 14-Oct-2020 / Published Date: 21-Oct-2020 DOI: 10.4172/2161-1165.1000392

Abstract

Scrub typhus (ST) is a rickettsial infection caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi (OT), which present with flu like symptoms. It is endemic in certain parts of world which includes South Asian region. This infection is associated with variable risk factors depending upon the geographical location, age and lifestyle patterns. In India, this disease has been reported from all the directions but with slight variations in its pattern. Thus to decrease the prevalence, prevent new incidences and predict the course of disease, knowledge and perception of local risk components which are associated with ST is crucial. Present study is about distribution pattern of OT infection among local population of Eastern Uttar Pradesh (EUP) region. It was found that EUP is an endemic region for ST infection which is mainly because of association of local folk with pets/cattle/rodent and agricultural work.

Keywords: Scrub typhus; Orientia tsutsugamushi; Zoonotic infection; Eastern Uttar Pradesh; Rickettsial infection

Introduction

Scrub typhus [ST] is a rickettsial zoonotic infectious disease which is also identified as Tsutsugamushi disease or Tsutsugamushi fever or bush typhus. It is caused by a gram negative obligate intracellular bacterium known as Orientia tshushugamushi. This bacterium is arthropod-borne which survives mainly in larvae (chiggers) of trombiculid mites and spread to human when these infected chiggers bite humans [1-3]. ST is often considered as occupational disease of rural population since chances of exposure to infected chiggers are more in rural areas [4].

This disease usually exhibits a spectrum of signs and symptoms including, pyrexia (may or may not with chills), headache, myalgia body-ache, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, non-pruritic macular or maculo-papular rash (not all the times), eschar, a pathognomonic sign of scrub typhus which is a dark scab like lesion at the site of bite (sometimes goes unnoticed). However, enlarged lymph nodes, mental changes ranging from confusion and encephalitis to coma have also been reported [5,6].

Epidemiology of scrub typhus

Globally, ST is endemic in certain geographical area known as “tsutsugamushi triangle”. This area covers around 8 million km2 of land and extends from eastern Russia in the north to Australia in the south, and from Japan in the east to Pakistan in the west [7,8]. Lately, people have gained interest in travelling and exploring different parts of world, which has rooted the transmission of such infections to non-endemic regions as well [9].

In India

In India for the first time, this infection was noted near Kumaon hills in 1938 [10]. In 1945 few serological positive cases of ST came into light from Uttar Pradesh [11]. In 2012, National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) declared an outbreak of this bacterial infection from many Indian states [12]. Later, quite a good number of cases were reported from different parts of the country presenting with wide range of signs and symptoms including even death [13-27].

This study is an attempt to find distribution and identify risk factors associated with ST infection in Eastern Uttar Pradesh [EUP]. The potential risk elements considered in this study were occupation, gender, age, seasonal variation, geographical location, surrounding of residence and pets.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted in the Viral Research and Diagnostic Laboratory (VRDL), Department of Microbiology, Institute of Medical Sciences, BHU, Varanasi, over a period of 6 months i.e. September 2019 to February 2020. All the suspected patients were required to submit the detailed case history form (CRF) filled by their physicians along with blood samples. The ST testing and this study were cleared by the Institutional Ethical Committee. The outpatient department (OPD) or admitted indoor patients from medicine and pediatric OPD with fever of unknown origin (more than 6 day) along with associated symptoms such respiratory distress; acute renal failure, acute liver failure, and/ or rash were recruited in this study with their blood samples for ST screening.

Specimen collection and laboratory testing

Blood samples were kept at room temperature for 30-60 min for separation of serum and then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min to obtain serum [28], which were stored in duplicate in VRDL lab for further analysis.

Serologic Analysis

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to detect the presence of antibodies (IgM) against Orientia tsutshugamushi in the suspected serums, which was done using InBios Scrub Typhus Detect™ IgM ELISA kit. ELISA was performed as per the instructionmanual provided by manufacturer along with the kit. Optical density (OD) value >0.5 was considered as cut off value since the same value was used in previous studies [29,30].

Variables

CRFs of all positive cases were retrieved from VRDL data storage section. The data were analyzed for details like age, gender, address of the patient, onset date of illness, duration of illness, duration of fever, systemic examination findings, signs and symptoms and along with that contact numbers were also obtained. Patients were contacted by VRDL staff to gather information regarding pets at their houses (if any), toilet facility in house, travel history, nature of area surrounding patients home, and occupational details.

Statistical analysis

The data obtained from the CRFs and the number of cases with specific sign and symptoms were analyzed and presented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) using Sigma-Plot statistical software (Version 11.0). Further, the comparison in terms of frequency, percentage, and means values were made with Student ‘t’ test. The p ≤ 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Serological assay findings

Out of 211 serum samples which were subjected to ELISA for ST, 58 samples (27.4%) were found to be positive for IgM antibodies against Orientia tsutshugamushi bacterium. These patients were contacted to retrieve further information.

Epidemiological data

Out of 58 (30 males and 28 females), we could not contact 15 patients thus we were left with minimal details about them. Table 1 shows the information we gathered after telephonic communication conducted with respective patients. Out of 43 patients who answered the phone calls, 76.7% were from rural area or had bushes around their houses, 88.3% had pets or cattle or frequent encounter with rodents at their houses and 30.3% didn’t have toilet facility at home. Occupation wise, most of them were students as they were young and majority of remaining subjects were involved with farms or cattle keeping occupations.

| S.No | Total no. of positive cases = 58 | Information obtained from = 43(100%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pets/rodents/cattle at home | Yes | 38 (88.3%) |

| No | 5 (11.7%) | ||

| 2 | Bushes around house/village area | Yes | 33 (76.7%) |

| No | 10 (23.3%) | ||

| 3 | Occupation | Most of them were students or associated with farm or cattle business (90%) | |

| 4 | Toilet facility at home | Yes | 30 (69.7%) |

| No | 13 (30.3%) | ||

Table 1: Detailed description of positive ST cases.

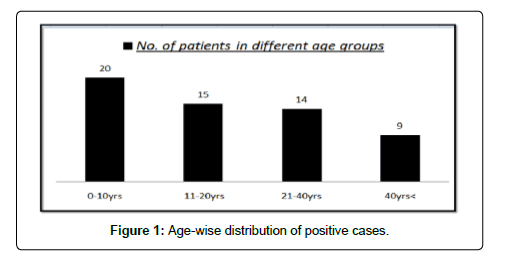

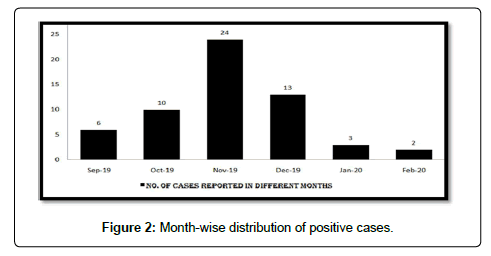

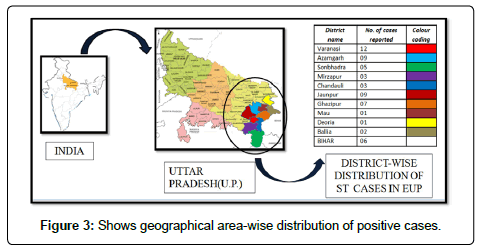

Prominent symptoms reported

Most of the patients presented wide range of symptoms, ranging from fever to death. Ambit of most common symptoms contained: headache, body-ache, chills, skin rashes, abdominal pain, vomiting, jaundice and altered sensorium. Figure 1 shows age-wise distribution of positive cases. Figure 2 depicts month-wise distribution of cases where out of 6 studied months, maximum cases were reported in November. Figure 3 reflects geographical distribution.

Discussion

ST is a less-discussed and under-diagnosed bacterial infection in the world. It often mimics other infections which makes it difficult for physician to diagnose as it does not have any specific pathognomonic set of clinical signs or symptoms [31,32]. If it goes undiagnosed, it can set the wheels of severe complications including death in motion. An “Eschar” at the site of chigger-bite could be the identifier for the disease, but its presentation has been reported with a wide range of variations 1-97% in various geographical regions which does not make it a reliable.

ST surfaced in India in early 90s but could not bloom out much owing to advances in application of insecticides, improved lifestyle and empiric management of PUO. But, last decade has drawn attention towards this disease as it witnessed enormous number (around 20% of total acute encephalitic syndrome (ASE) cases reported in India from 2010 to 2016) of ST positive cases from India [33,34]. Epidemiological studies have concluded that ST occurs throughout India with prevalence rate ranging from 4.27% to 47.48% and states which have history of presenting good number of cases are Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Odisha, West Bengal, Manipur, Tripura, Assam, Uttar Pradesh [1,33,35,36]. Prevalence rate unveiled by the present study is ~27%.

In our study, we retrieved details of 58 ST positive residents of EUP and adjacent Bihar. Most of them were from rural area, many were involved in open field /farm or cattle keeping occupations and belonged to younger age groups (Table 1 and Figure 1). Attributable reasons for these findings can be that in rural areas chiggers have easy access to human as the houses are surrounded by scrub vegetations/ bushes or farm area, younger age group tends to involve in more outdoor activities which enhances their odds of getting in contact with chiggers. Xu G et al 2107, in their review, marked socioeconomic status and rural residential area as two of the important risk factors associated with ST in India. Stephen et al 2013, reported that in parts of South India, field workers, patients who didn’t cover their bodies at home and who had bushy neighborhood were at greater risk of acquiring ST than others [20]. Age distribution of present study however does not match the results from other countries like Japan where 62% ST positive cases were reported under 51-75 year age group [37]. Since the female and male ratio was 1:1.1, no gender predilection was observed which is in concordance with previous studies [38]. On other hand, few countries like South Korea have reported increased inclination of ST towards females [39].

Approx 30% of ST positive patients did not have toilet facility. Squatting to defecate or urinate in agricultural field/bushes increases the chances of getting in contact with mites by many folds [40,41]. Thangaraj et al 2017, found open-field-defecation as the most common element among ST patients. Data on ST outbreak from Manipur also point-outs towards population who relived themselves in bushy areas/ jungles as “high risk” group for ST.

Data obtained from this study reveals that EUP is endemic region for this vector-borne infection as it could be detected in all the 6 months which were included in the study period. The highest percentage of cases could be observed in the month of November (41.3%). This finding is in concordance with study reported by Bhargava A et al., 2016. South Indian states have reported maximum number of cases during cooler season when compared to other parts of India.

The highest risk factor of getting infected with OT, pointed out by this study is having pets/rodents/cattle at home. About 88.3% of patients had frequented their homes by pets/rodents or had cattle in their homes. Rodents, pets and cattle are often infested with OT vectors and thus help it to get in contact with humans. Other risk elements which were highlighted in previous studies are existence of water-body closer to residence, preparation of meals outside the residence, children travelling to school in a vehicle, drying clothes on grasses or bushes, taking bath in water-bodies, storing firewood inside the house and carrying fodder/grass stacks on head [42]. Geographical distribution of data from this study reflects that, EUP has endemic proportion as for as ST is concern as shown in Figure 2. Majority of cases were from Varanasi which could be because of proximity of the university hospital to these people.

Based on findings of this study following preventive measures are recommended. Use of insect-repellents, wearing long clothes, closeshoes and hat/head cover must be recommended for population who work in field/farms/vegetable gardens or animal husbandry to decrease infection of scrub typhus. In addition to that, use of insecticides in disease-prone area, maintenance of clean surrounding habitat and improved sanitary standards along with complete stoppage of open field defecation will also help to reduce the odds of ST infection.

Conclusions

With the changing epidemiology of scrub typhus and some limitations of this study, following conclusions can be drawn out of this study:

• Proximity to pets/cattle/having rodents in closer vicinity, residence surrounded by vegetation/farm/bushy area and occupation involving field work, increases the chances of getting bitten by mites/ chiggers.

• An early diagnosis and management can help to prevent disease complications.

• Overall, in EUP, an increasing awareness with respect to clinical features, disease presentation, and laboratory diagnosis can help our community to reduce the mortality caused by this infectious disease.

Acknowledgement

Authors gratefully acknowledge the support provided by Department of Health Research under the Ministry of Health & Family Welfare (Government of India), New Delhi, India and Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) in the form of establishment of State Level Viral Research and Diagnostic Laboratory (VRDL) network under scheme 5066.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest declared.

References

- Xu G, Walker DH, Jupiter D, Melby PC, Arcari CM (2017) A review of the global epidemiology of scrub typhus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11: e0006062.

- Paris DH, Shelite TR, Day NP, Walker DH (2013) Unresolved problems related to scrub typhus: a seriously neglected life-threatening disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg 89: 301-317.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Division of Vector-Borne Diseases (2019).

- Shukla A, Gangwar M, Rastogi S, Nath G (2019) Viral Encephalitis: A hard nut to crack. Annals of the National Academy of Medical Sciences 55: 98-109.

- Shikino K, Ohira Y, Ikusaka M (2016) Scrub Typhus (Tsutsugamushi Disease) presenting as fever with an Eschar. J Gen Intern Med 31: 582.

- Seong SY, Choi MS, Kim IS (2001) Orientia tsutsugamushi infection: Overview and immune responses. Microbes and Infection 3: 11-21.

- Izzard L, Fuller A, Black sell SD, Paris D H, Richards AL, et al. (2010) Isolation of a novel Orientia species (O.chutosp.nov.) from a patient infected in Dubai. J Clin Microbiol 48: 4404-4409.

- Kuo CC, Huang JL, Shu PY, Lee PL, Kelt DA, et al. (2012) Cascading effect of economic globalization on human risks of scrub typhus and tickâ€borne rickettsial diseases. Ecological Applications 22: 1803-1816.

- Blewitt B (1938) Fevers of the typhus group in the Bhimtal area of Kumaon hills. J Royal Armed Corps 70: 241-245.

- Padbidri VS and Gupta NP (1978) Rickettsiosis in India: a review. J Indian Med Assoc 71: 104-107.

- Mittal V, Bhattacharya D, Chhabra M (2013) Multi-state outbreak of scrub typhus. NCDC News 2: 3-4.

- Bhargava A, Kaushik R, Kaushik RM, Sharma A, Ahmad, et al. (2016) Scrub typhus in Uttarakhand & adjoining Uttar Pradesh: Seasonality, clinical presentations & predictors of mortality. Indian J Med Res 144: 901-909.

- Batra HV (2007) Spotted fevers & typhus fever in Tamil Nadu. Indian J Med Res. 126: 101- 103.

- Kamarasu K, Malathi M, Rajagopal V, Subramani K, Jagadeeshramasamy D, et al. (2007) Serological evidence for wide distribution of spotted fevers & typhus fever in Tamil Nadu. Indian J Med Res. 126: 128-130.

- Mathai E, Rolain JM, Verghese GM, Abraham OC, Mathai D, et al. (2003) Outbreak of scrub typhus in southern India during the cooler months. Ann NY Acad Sci 990: 359- 364.

- Isaac R, Varghese GM, Mathai E, Manjula J, Joseph I (2004) Scrub typhus: prevalence and diagnostic issues in rural southern India. Clin Infect Dis 39: 1395-1396.

- Vivekanandan M, Mani A, Priya YS, Singh AP, Jayakumar, et al. (2010) Outbreak of scrub typhus in Pondicherry. J Assoc Physicians India 58: 24-28.

- Stephen S, Kandhakumari G, Vinithra SM, Pradeep J, Venkatesh C, et al. (2013) Outbreak of pediatric scrub typhus in South India- A preliminary report. J Pediatr Infect Dis 8: 125-129.

- Stephen S, Kandhakumari G, Pradeep J, Vinithra SM, Siva PK, et al. (2013) Scrub typhus in south India: a re-emerging infectious disease. Jpn J Infect Dis 66: 552-554.

- Boorugu H, Dinaker M, Roy ND, Jude JA (2010) Reporting a case of scrub typhus from Andhra Pradesh. J Assoc Physicians India 58: 519-520.

- Sundhindra BK, Vijayakumar S, Kutty KA, Tholpadi SR, Rajan RS, et al. (2004) Rickettsial spotted fever in Kerala. Natl Med J India. 17: 51-52.

- Singh SI, Devi KP, Tilotama R, Ningombam S, Gopalkrishna Y, et al. (2010) An outbreak of scrub typhus in Bishnupur district of Manipur, India. Trop Doct 40: 169-170.

- Ahmad S, Srivastava S, Verma SK, Puri P, Shirazi N (2010) Scrub typhus in Uttarakhand, India: a common rickettsial disease in an uncommon geographical region. Trop Doct 40: 188-190.

- Chaudhry D, Garg A, Singh I, Tandon C, Saini R (2009) Rickettsial diseases in Haryana: not an uncommon entity. J Assoc Physicians India 57: 334- 337.

- Sharma A, Mahajan S, Gupta ML, Kanga A, Sharma V (2005) Investigation of an outbreak of scrub typhus in the himalayan region of India. Jpn J Infect Dis 58: 208-210.

- Digra SK, Saini GS, Singh V, Sharma SD, Kaul R (2010) Scrub typhus in children: Jammu experience. JK Sci 12: 9-7.

- Tuck MK, Chan DW, Chia D, Godwin AK, Grizzle WE, et al. (2008) Standard operating procedures for serum and plasma collection: early detection research network consensus statement standard operating procedure integration working group. Journal of proteome research 8: 113-117.

- Varghese GM, Trowbridge P , Janardhanan J, Thomas K, Peter JV, et al. (2014) Clinical profile and improving mortality trend of scrub typhus in South India. Int J Infect Dis 23: 39-43.

- Thangaraj JWV, Vasanthapuram R, Machado L, Arunkumar G, Sodha SV, et al. (2017) Scrub Typhus risk factor study group. risk factors for acquiring scrub typhus among children in Deoria and Gorakhpur Districts, Uttar Pradesh, India. Emerg Infect Dis 24: 2364-2367.

- Watt G (2010) Scrub typhus. In: Warrell DA, Cox TM, Firth JD, editors. Oxford textbook of medicine, (5th ed), Oxford University Press, Oxford, USA pp: 7-40.

- Phasomkusolsil S, Tanskul P, Ratanatham S, Watcharapichat P, Phulsuksombati D, et al. (2012) Influence of Orientia tsutsugamushi infection on the developmental biology of Leptotrombidium imphalum And Leptotrombidium chiangraiensis (Acari: Trombiculidae). J Med Entomol 49: 1270-1275.

- National Vector borne Disease Control Program. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India (2016). Statewise number of AES/JE cases and deaths from 2010- 2017.

- Khan SA, Bora T, Laskar B, Khan AM, Dutta P (2017) Scrub typhus leading to acute encephalitis syndrome, Assam, India. Emerg Infect Dis 23: 148- 150.

- Sethi S, Prasad A, Biswal M, Hallur VK, Mewara A, et al. (2014) Outbreak of scrub typhus in North India: a re-emerging epidemic. Tropical doctor 44: 156-159.

- Chrispal A, Boorugu H, Gopinath KG, Prakash JA, Chandy S, et al. (2010) Scrub typhus: an unrecognized threat in South India–clinical profile and predictors of mortality. Tropical Doctor 40: 129-133.

- Ogawa M, HagiwaraT, Kishimoto T, Shiga S, Yoshida Y, et al. (2002) Scrub typhus in Japan: epidemiology and clinical features of cases reported in 1998. AmJ Trop Med Hyg 67: 162-165.

- Zhang WY, Wang LY , Ding F, Hu WB, Soares, et al. (2013) Scrub typhus in mainland China, 2006-2012: the need for targeted public health interventions. PLoS Negl Trop Dis7: e2493.

- Lee HW, Cho PY, Moon SU, Na BK, Kang YJ, et al. (2015) Current situation of scrub typhus in South Korea from 2001-2013. Parasit Vectors 8: 238.

- Kweon SS, Choi JS, Lim HS, Kim JR, Kim KY, et al. (2009) A community based case-control study of behavioral factors associated with scrub typhus during the autumn epidemic season in South Korea. Am J Trop Med Hyg 80: 442-446.

- Varghese GM, Raj D, Francis MR, Sarkar R, Trowbridge P, et al. (2016) Epidemiology & risk factors of scrub typhus in south India. Indian J Med Res 144: 76-81.

- Rose W, Kang G, Verghese VP, Candassamy S, Samuel P (2019) Risk factors for acquisition of scrub typhus in children admitted to a tertiary centre and its surrounding districts in South India: a case control study. BMC Infect Dis 19: 60-65.

Citation: Alka S, Mayank G, Akanksha S, Sonam R, Deepak K, et al. (2020) Epidemiological Distribution and Potential Risk Factors of Orientia Tshushugamushi Infection in Eastern Uttar Pradesh, India. Epidemiol Sci 10: 392 DOI: 10.4172/2161-1165.1000392

Copyright: © 2020 Alka S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 3182

- [From(publication date): 0-2020 - Nov 22, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 2322

- PDF downloads: 860