Research Article Open Access

Environmental Obligations and Social Engineering: A Case Study of Evicted Community from Dal lake, Kashmir

Shabina Arfat1*, and Mudasir Ali2*

1Faculty of Law, University of Kashmir, Hazratbal, Srinagar - 190006, Kashmir, India

2Department of Environmental Sciences, University of Kashmir, Srinagar - 190006, Kashmir, India

- *Corresponding Author:

- Mudasir Ali

Department of Environmental Sciences

University of Kashmir

Srinagar - 190006, Kashmir, India

E-mail: wild_defenders@yahoo.com - Shabina Arfat

Faculty of Law

University of Kashmir, Hazratbal

Srinagar - 190006,Kashmir, India

E-mail: arfatshab9@gmail.com

Received Date: April 23, 2013; Accepted Date: May 13, 2013; Published Date: May 20, 2013

Citation: Arfat S, Ali M (2013) Environmental Obligations and Social Engineering: A Case Study of Evicted Community from Dal lake, Kashmir. J Civil Legal Sci 2:103. doi:10.4172/2169-0170.1000103

Copyright: © 2013 Arfat S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Civil & Legal Sciences

Abstract

This work explores empirical and theoretical perspectives on land acquisition for the protection of environment accompanied by rehabilitation of the evicted community. Land acquisition followed by resettlement of affected fishermen community apparently had an overall good impact on the evicted population. The work reveals that resettlement has not compromised the basic requirements of the evictees; however, further steps are required to be taken to make the said eviction in consonance with the guidelines of the Supreme Court. There is a constitutional imperative on the State Government, not only to ensure and safeguard proper environment but also an imperative duty to take adequate measures to promote, protect and improve both the man-made and the natural environment. Social justice, equality and dignity of person are the corner stones of social democracy. The expression ‘life’ in Art.21 of the Constitution has a much wider meaning which includes right to livelihood, better standard of life, hygienic conditions and protection of environment.

Keywords

Environmental protection; Restoration; Rehabilitation; Land acquisition; Eviction; Displacement; Resettlement; Right to life; Law

Introduction

Restoration means returning a site to a target condition. The target condition may not be the same as the pre disturbance condition, but it is usually based on a desired level of function. Rehabilitation refers to the activities carried out to meet that primary goal [1]. Ecological restoration is the process of assisting in the recovery of ecosystems that have been damaged, degraded, or destroyed [2]. ‘Recovery’ implies a return to the original state and it is usually preferred to use the term ‘rehabilitation’ [3]. Rehabilitation measures are employed to help reach restoration goals but are not goals in themselves. Rehabilitation measures generally fall into two main categories:

1. Process-based - those that facilitate natural recovery processes.

2. Structure-based - those that utilize engineered works [1].

Once restoration areas are prioritized, it is important to set specific restoration goals and project objectives. The type of treatment selected may also depend on other factors, such as legislated requirements for site remediation and the expected time frames for different approaches to achieve the desired results. Providing information on experimental designs, techniques, and monitoring is an important part of improving restoration projects [4]. Ideally, monitoring strategies and effectiveness evaluation criteria are determined at the project outset and incorporated throughout the planning and implementation phases. Conducting a risk analysis is also strongly recommended as part of restoration planning. Unfortunately, although effectiveness evaluation may be the greatest source of restoration information for adaptive management, few funding agencies are willing to commit to years of monitoring. To truly understand the effectiveness of restoration projects and rehabilitation treatments, it is critical to evaluate the effectiveness of the work against the original objectives and overall goals [1]. In addition to using ecological boundaries, the ecosystem approach requires that governments move away from a single medium, water quality objectives based model to one that addresses multiple stresses on the ecosystem and their interactions while pursuing the critical objectives of restoration and maintenance of ecosystem integrity [5].

Environmental obligations and need for the protection of the freshwater resources is being advocated worldwide to ensure that the pristine glory of the natural assets is restored or maintained. In recent years, eviction from encroached areas of Dal Lake by the government, in the form of land acquisition followed by resettlement of evicted population, is a welcome step towards balancing of duties vis-avis environmental protection and rehabilitation of affected people. Resettlement or rehabilitation is needed under two situations:

1. Where the land is acquired for the installation of services which are intended to benefit a large section of the society.

2. Where the land has been illegally occupied but the duration of stay by the offenders is a long one, and therefore, resettlement [6] or rehabilitation [7] of such people by the Government becomes imperative.

Problem statement

The Dal Lake is a major attraction to local and foreign visitors alike. The myriad of problems faced by the Dal Lake and state management authorities include encroachment upon the open water and its transformation to the dry-land. A portion of the Dal Lake was transformed to a dry-land nearby to the fore-shore road, the road which commences near the Naseem Bagh, Habak and ends at the Shalimar and Nishat areas of the Srinagar and covering a portion of the perimeter of the Lake. The place locally used to be called as ‘Dhoh’ or as Sidiq-Dag Mohalla, was constructed some 100 meters ahead in the open water which was connected to the main road by a short strait-like pathway. Following the conservation steps, the lake management authorities finally in the year 2000 forcibly evicted the settled population and dredged out the dry-land from the Dal Lake, but provided the population with an alternative land nearby to the Lake. Previous attempts to remove the people from the lake included mere serving of the eviction notices but yielded no response. The present study endeavours to assess the impact of the said resettlement on the displaced population of the Fishermen Community.

The main objectives of the study included:

1. To observe, whether adequate or necessary facilities were provided under the resettlement measures to the displaced population;

2. To observe the likely impact (both positive and negative) upon the displaced population following the resettlement especially with respect to the economy and children education.

The motivation for the study was to provide inspiration for a comprehensive strategy for the restoration of the lake and its future survival and management by sampling a portion of the displaced people from the lake and studying the effects on them brought about by the displacement.

Study area

The beauty of the Dal Lake, the lake par excellence of Kashmir, can be perceived better in the description provided by Lawrence [8], “The Dal Lake, measuring about 4 miles by 2½, lies close to Srinagar, and is perhaps one of the most beautiful spots in the world. The mountain ridges which are reflected in its waters, as in a mirror, are grand and varied, the trees and vegetation on the shores of the Dal being of exquisite beauty.” Resembling with the ‘chinampas’ of old Mexico, the floating gardens of the Dal lake find an appreciation by the Lawrence [8] who describes the making of the floating gardens as: “The rádh, or floating gardens, are made of long strips of the lake reed, with a breadth of about six feet. These strips can be towed from place to place and are moored at the four corners by poles driven into the lake bed. When the rádh is sufficiently strong to bear the weight of a man heaps of weed and mud are extracted from the lake by poles, and these heaps are formed into cones and placed at intervals on the rádh.”

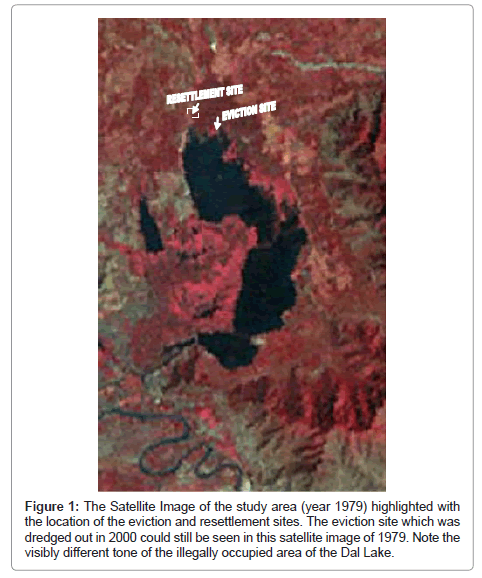

The study area comprised the resettled ‘Fishermen Community’ situated nearby to the Hazratbal basin of the Dal Lake at a distance of about 200 meters from the lake periphery and lying at a distance of about 1.2 kilometres from the eviction site (Figure 1). One of the satellite location points recorded using a Global Positioning Satellite receiver (Garmin, 12 Channel GPS, model e TrexCamo) at the resettlement site shows its spatial location as: N 34° 09’ 01.4”, E 074° 50’ 41.6”, Elevation 1590 meters, with a positional error of ±4 meters. The resettlement site is connected with the Dal Lake through a narrow navigation channel which provides the passage to the fishermen boats.

Figure 1: The Satellite Image of the study area (year 1979) highlighted with the location of the eviction and resettlement sites. The eviction site which was dredged out in 2000 could still be seen in this satellite image of 1979. Note the visibly different tone of the illegally occupied area of the Dal Lake.

Design of the Study

To accomplish the objectives, the study (conducted in 2008) was designed on a scientific basis for which a standard methodology was followed.

Sampling and sample size

The sample population comprised of the same displaced families which were evicted from a portion of the Dal Lake and resettled nearby to the Lake. The sample from the study population was selected on a random basis. The random sampling approach is justified because the universe of the study consisted of homogeneous population who are nearly equally positioned so far as their economy, culture, tradition, occupation, income, education, caste, etc. are concerned. The sample size constituted a total of 30 subjects of both genders in the age group of 35 - 60.

Methodology

For the collection of information, a well designed questionnaire was drafted which covered all the facets of the study. The questionnaire schedule covered the aspects of the study which included the information on the population composition, occupations, compensations in the form of property and dismantling charges, alternative land allocations, past and present income status and occupations as well as the children education; and other necessary information in the form of provision of such facilities as shelter, water, electricity, schooling, wastewater drainage, medical and theological provisions. In addition the other relevant information connected with the study was also collected especially from the heads of the community. Literature review was done to obtain the information relevant to the study. The sources comprised of books, journals, management reports, and judgments of the court.

Results and Discussion

The information presented below is mostly based on the direct observations collected in the field and mostly relies on the responses of the respondents. The phase of inquiries could be stated by starting with the history of the emergence of the subject population in the said dredged area of the Dal Lake. According to the respondents, few families in the past extended their horizons by migrating from the resident community of Dal near the grave of Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah and built up the community near the fore-shore road which was used to be called ‘Dhoh’, or more properly as Dag Mohala. The common practice of building floating gardens was used but later on due to its proximity to the road, the land was filled with soil, mud, boulders, etc. which supported the platform for the construction of the permanent structures. As per respondents, the said piece of land spread over an area of approximately 8 kanals (one acre/ 4047 sq meters). It supported a group of about 30 joint families, and as such of only about 30 houses. But the said population in fact consisted of about 72 choolas or sub-families with an approximate population of 100 - 150 individuals at the time of displacement. In addition, the respondents claim to have Nadru (Nelumbium) cultivation over approximately 20 kanals of water-land against which they used to pay the required taxes (maumlas) towards the government. Following the steps for restoration of the Dal Lake, notices of eviction were served to the said community. But the negative response by the respondents led to the forcible eviction of the population and acquisition of the land by the Lake authorities in the year 2000. The place was then dredged out of the Lake. However, the population was resettled nearby to the Dal Lake and the location has been named as ‘Fishermen Colony’ which lies at a distance of about 1.2 kilometres from the place of displacement. The place is connected to the Lake through a navigation channel which provides the passage to the fishing boats.

After following steps under Land Acquisition Act, each family was compensated within 15 days time. They were given alternative land within one kilometre range from the re-acquired land. As being located nearby to the Dal Lake they felt at home at the resettled place. The Land Acquisition Collector fixed the dismantling charges/ compensation as per the market value. The new resettled colony has been named as ‘fishermen colony’. It is submitted that the resettlement scheme is properly and satisfactorily implemented to a larger extent and the government has balanced both the sides, viz environmental protection and resettlement of displaced people.

The respondents were asked about why there was a need for the displacement or acquisition of land by the Government. The respondents feel that there was a need for the acquisition of land as they, among many other factors, were responsible for the pollution of the Dal Lake. They admitted that it was only because of the pollution of water body that some of the fishes have almost become extinct or very much dwindled in the production. So far as the other species of fish are concerned there is tremendous decrease in their production, thereby affecting not only the diversity of animal species but also their economy. Another important factor for the dislocation as assumed by the respondents was the unsightly location within the Lake which was considered as aesthetically unappealing from the tourism point of view.

The respondents were striking in their environmental knowledge. The major contributing factor at present responsible for the deterioration of the Dal Lake according to the respondents is the sewage water that the government has directed towards the lake through the drainage network. The wastewater also possesses the solid materials especially the polythene which is choking the lake, as quoted by some respondents.

Regarding the amount of compensation for the property in the form of dismantling charges, etc. paid to the displaced population, the respondents were reluctant in answering the amount of compensation paid. Only 53.33 % of the respondents responded to the query. The reported compensation amounts are presented in the Table 1. Fifty per cent of the respondents reported the compensation amounts in the range of Rs. 1,00,000 - 2,50,000 (Table 1). In addition, Rs. 60,000 was given as the dismantling charges towards the Mosque. However, the respondents claim that their Nadru cultivation (measuring about 20 kanals) has neither been compensated yet nor are they hopeful of getting this compensation because of the low response by the authorities.

| Amount of compensation paid | Percentage of respondents reporting |

|---|---|

| Rs. 30,000 – 50, 000 | 18.75 % |

| Rs. 50,000 – 1,00,000 | 6.25 % |

| Rs. 1,00,000 – 1,50,000 | 25 % |

| Rs. 1,50,000 – 2,00,000 | 6.25 % |

| Rs. 2,00,000 – 2,50,000 | 18.75 % |

| Rs. 2,50,000 – 3,00,000 | 12.5 % |

| Rs. 3,00,000 – 3,50,000 | 6.25 % |

| Rs. 3,50,000 – 4,00,000 | 6.25 % |

Table 1: Reported compensation amounts paid to the displaced families

The alternative land allocated to the displaced families were allotted as ‘plots’ having the dimensions of 50 feet x 30 feet. Each 50’ x 30’ measuring plot was provided against a cash payment of Rs. 4, 530 by the displaced families. 72 plots were provided to the 72 families. Later on upon the request by the displaced population, one plot each was provided for a Mosque and a Graveyard.

At the time of resettlement, choice was given by the government that they can either build their own houses out of dismantling compensations or government can reconstruct a residential colony for the displaced families. In this connection a “model house” was also constructed as a sample but the respondents rejected the latter choice as the brick wall of the model-house was only 4 inches in thickness. According to the respondents it was not strong and it was impossible to construct a second storey on the weak foundation. Moreover, they were worried about the quality of the materials which the contractors were going to use in the buildings. The said model house was later on used as a middle school.

The respondents have built strong concrete houses within a period of eight years, each having an average of about 3 to 5 rooms, including a Kitchen. In addition, now they also have a yard of their own.

The respondents agreed that the resettlement has brought positive changes in the form of availability of various facilities especially the shelter, drinking water, electricity, drainage, and access to roads and basic sanitation. One dispensary has also been made available but the respondents are not satisfied with its services.

The respondents were asked regarding the impact of resettlement on the education of the children. All the respondents acknowledged that the resettlement has brought a very good effect on the education of the children and their children are now acquiring education. The government has provided the schooling facility at the resettled location for the children of the displaced fishermen. There is a Middle School in the locality. About 50 students (both girls & boys) are getting education there. Only two teachers are in charge of the school, including one teacher from the said fishermen community employed under the rehbar-i-taleem scheme.

Each and every family is now sending their children to the school right from the 5 - 6 years of age. Before displacement, only some of them used to admit their children in the school and often after 7-8 years of age. For some or other reason their children used to discontinue their education quite early. The respondents noted that only half of the children from some families used to get education earlier but now there has been a quite good transformation brought about by the resettlement with nearby school facility within the community.

The only striking negative impact that the respondents expressed was that there has been a near 50 percent reduction in their monthly income so far as their fishing occupation is concerned. The respondents attribute this to several factors and the main factor responsible was believed to be the reduction in the fish production from the lake. This has made them dependent on the fishes from other locations which they purchase and resell in various markets. According to respondents they are getting low profits by the resale of the fish and the direct benefits which could have been accrued from the self catches have got minimal. Some respondents reported that the comparatively far off location from the Dal makes them unable to perform night time fish catching operation.

According to the respondents, there are about 200 fishing license holders but among them only about 100 are active fishermen. The present annual license fee levied from them by the Government is reportedly Rs. 500/- per license plus a monthly fee of Rs. 200/- as the costs against the possible catch of the yearlings.

Another impact which the respondents report is that the younger generation is not now motivated to continue their traditional occupation and make a likely shift to other professions. Majority of the boys (> 80 %) have changed their occupation and resort to other kinds of work chiefly the labour works and also as carpenters, masons, drivers, tailors, salesmen and as automobile repairmen. Before resettlement, the major occupation prevalent among the community was only fishing. Some respondents claim that the resettlement has increased the opportunities of getting shifted to other works, where they can make a profitable income to negate the impact of low benefit from the fishing occupation coupled with the low fish production from the lake. Although there has been a 50 % decrease in their monthly income as far as the fishing occupation is concerned but so far as the change of occupation by the younger generation is concerned it has added to their monthly income and as such the losses have been compensated to a certain extent.

The women folk play a major role in the family as they support the men in earning their livelihood. Only the married women go to the market for the sale of fish. One or two women from each family perform this duty depending on the family size. The fish catching has now been to a maximum extent replaced by the purchase of fish from traders and the involvement of men has got diminished in its scope. This factor on the other hand has made the men folk free for pursuing other occupations and therefore, adding to the economy of their families, but at the same time making many men jobless especially the elderly population. Presently there are about 130 - 150 working women in the community of the evictees.

The women respondents claim that their household monthly income before the eviction used to be in the average range of Rs. 5000 - 6000 when they used to pursue the fish catch themselves from the Lake but presently they only get about Rs. 2000 - 2500 from the fishing occupation.

Some of the unmarried girls are also associated with some sort of minor works. After resettlement, the unmarried and young girls are doing the Pashmina knitting (Rufugari) thereby making a marginal earning. This is one of the factors responsible for the early school discontinuation and therefore, needs to be overcome by the Government by providing incentives to the poor people.

The respondents were also asked about the problems being currently faced by the resettled population. The problems reported and the wishes expressed by the respondents are summarized below.

1. Reduction in income: As the economy connected with the fishing occupation has got reduced the respondents request that some loan facilities based on non-interest terms should be made available to the displaced community.

2. Compensation for Nelumbium: Since the Nadru (Nelumbium) cultivation has never been compensated, the displaced families strongly hope that they should be provided compensation to the said previously occupied cultivation.

3. Improvements over roads and wastewater drains: The respondents wish that the roads be tarred in the area. The houses are yet to be connected to the constructed drainage network and are using temporary sumps for the time being.

4. Provision of a community park or a playing ground: The respondents wished that a community park and a playing ground for the children be provided by the government.

Legislative enactments, judicial interpretation and social engineering

The right to environment finds support from some of the key principles and doctrines. The ‘polluter pays’ principle or ‘liability of the polluter’ principle has been interpreted to mean that the absolute liability for harm to the environment extends not only to compensate the victims of pollution but also the cost of restoring the environmental degradation. Remediation of the damaged environment is part of the process of ‘Sustainable Development’ and as such the polluter is liable to pay the cost to the individual sufferers as well as the cost of reversing the damaged ecology. The public trust doctrine, incorporated into the principles of international environmental law, refers to the idea that nature, the environment, the air, running water, and the sea are common to all humankind. Three main attributes of public trust doctrine as recognized by the courts can be listed. First, the property subject to the trust must not only be used for a public purpose, but it must be held available for use by the general public; second, the property may not be sold, even for a fair cash equivalent; and third, the property must be maintained for particular types of uses. The public trust doctrine as part of the jurisprudence has been widely observed in various litigations as: “The State as a trustee is under a legal duty to protect the natural resources. These resources meant for the public use cannot be converted into private ownership.” The Stockholm Declaration is regarded as ‘one of the foundation stones’ of sustainable development’. Principle 2 of the Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, 1972, sets out the principle of inter-generational equity: The natural resources of the earth, including the air, water, land, flora and fauna and especially representative samples of natural ecosystems, must be safeguarded for the benefit of present and future generations through careful planning or management, as appropriate.

The preamble and Art.38 of the Constitution of India - supreme law, envisions social justice as its cornerstone to ensure life to be meaningful and liveable with human dignity. The constitution demands justice, liberty, equality and fraternity as supreme values to usher in the egalitarian social, economic and political democracy. Social justice, equality and dignity of person are the corner stones of social democracy. The concept of ‘social justice’ in the Constitution of India consists of diverse principles essential for the orderly growth and development of personality of every citizen. Article 38 (1) lays down the foundation for human rights and enjoins the state to promote the welfare of the poor by securing and protecting, as effectively as it may, a social order in which social, economic and political justice shall inform all the institutions of the national life. Art. 46 direct the state to protect the poor from social injustice and all forms of exploitation. The expression ‘life’ in Art.21 of Indian Constitution does not connote mere animal existence or continued drudgery through life. It has a much wider meaning which includes right to livelihood, better standard of life, hygienic conditions in work place and leisure. Expanded connotation of life would mean tradition and cultural heritage of the persons concerned [9]. The constitution, therefore, mandates the state to accord justice to all members of the society in all facets of human activity. The concept of social justice imbeds equality to flavour and enliven practical connotation of life. Social justice and equality are complementary to each other so that both should maintain their validity. Rule of law, therefore, is a potent instrument of social justice to bring about equality and results. The phenomenon of poverty which is common to all developing countries has to be tackled on an all-India basis by making the gains of development available to all sections of the society through a policy of equitable distribution of income and wealth. The encroachments committed by the community are probably compelled by inevitable circumstances and are not guided by choice. Their intention is not to commit any offence [10]. The right conferred by Art. 19 (1) (c) of the Constitution to reside and settle in any part of India cannot be read to confer a license to encroach and trespass upon public property [10]. No person has a legal right to encroach upon or to construct any structure on a footpath etc [11]. Public health and safety cannot suffer on any count and all steps are to be taken as Art. 47 make it a paramount principle of Government that all steps are taken “for the improvement of public health as among its primary duties”.

The Indian legal system makes adequate provision for addressing water pollution problems in that there is:

1. A comprehensive scheme of administrative regulation through the permit system of the water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act of 1974.

2. Provisions of the Environment (Protection) Act of 1986 relating to the quality of water.

The supreme court of India and High Courts have given teeth to these laws by hearing public interest writ petitions that seek implementation of measures to prevent water pollution. The Indian legal system - based on English common law - includes the public trust doctrine as part of its jurisprudence. The public trust doctrine primarily rests on the principle that certain resources like air, sea, waters and forests are of such a great importance to the people as a whole that it would be wholly unjustified to make them a subject of private ownership. The said resources being a gift of nature, they should be made freely available to everyone irrespective of the status in life. The doctrine enjoins upon the Government to protect the resources for the enjoyment of the general public rather than to permit use for private ownership or commercial purposes.

Thus, the public trust is an affirmation of the duty of the state to protect the people’s common heritage of streams, lakes, marshlands and tidelands. The State has an affirmative duty to take public trust into account in the planning and allocation of water resources and to protect public trust whenever feasible [12]. The aesthetic use and pristine beauty of the natural resources, the environment and the ecosystem cannot be permitted to be eroded for private, commercial, or any other use unless the courts find it necessary, in good faith, for the public good and in the public interest to encroach upon the said resources. The public trust doctrine has vast potential and may serve as a touchstone to test executive action with a significant environmental impact [13]. The Environment (Protection) Act, 1986 [14] as well as the Water Act, 1974 [15] are equally applicable to Jammu and Kashmir.

Environmental protection and improvement were explicitly incorporated into the Constitution by the Constitution (42nd) Amendment Act of 1976 by inserting Article 48-A into the directive principles of state policy. It declares: ‘The state shall endeavour to protect and improve the environment and to safeguard the forests and wildlife of the country’. Art. 51-A (g) in a new chapter entitled Fundamental Duties, imposes a similar responsibility on every citizen ‘to protect and improve the natural environment including forests, lakes, rivers, and wildlife and to have compassion for living creatures’.

The boundaries of the fundamental right to life and personal liberty guaranteed in Article 21 (enshrined in Part III of the constitution) were expanded by the Supreme Court by including environmental protection. In India, the first recognition of the right to wholesome environment may be traced to the Dehra Dun Quarrying Case [16]: “Article 21 protects the right to life as a fundamental right. Enjoyment of life, including (the right to live) with dignity encompasses within its ambit, the protection and preservation of environment, ecological balance free from pollution of air and water, sanitation, without which life cannot be enjoyed. Any contra acts or actions would cause environmental pollution. Environmental, ecological, air, water pollution, etc. should be regarded as amounting to violation of Article 21. Therefore, hygienic environment is an integral facet of right to healthy life and it would be impossible to live with human dignity without a human and healthy environment. There is a constitutional imperative on the State Government and the municipalities, not only to ensure and safeguard proper environment but also an imperative duty to take adequate measures to promote, protect and improve both the man-made and the natural environment.”

The meaning of right to life has been expanded by the judicial interpretation and it includes right to the means of livelihood. The state cannot deprive a person or a population of their means of livelihood without following just, reasonable and fair process of law. Therefore while taking steps for displacing a population State is obliged to take into consideration the likely impact of dislocation on the livelihood of the concerned population. Hence State should take appropriate measures of resettlement/ rehabilitation and cannot arbitrarily deprive a population of their means of livelihood under the colour of environmental protection. The Supreme Court of India explained the right to livelihood in Olga Tellis vs. Bombay Municipal Corp. [17] as follows: “Right to life, includes right to the means of livelihood which makes it possible for a person to live. An equally important facet of that right (Art. 21) is the right to livelihood because; no person can live without the means of living, that is, the means of livelihood. If the right to livelihood is not treated as a part of the constitutional right to life, the easiest way of depriving a person of his right to life would be to deprive him of his means of livelihood to the point of abrogation. There is thus a close nexus between life and the means of livelihood and as such that, which alone makes it possible to live, leaves aside what makes life liveable, must be deemed to be an integral component of the right to life. But the constitution does not put an absolute embargo on the deprivation of life or personal liberty. Only it must be according to procedure established by law. Therefore, any Act which allows the deprivation must satisfy Art. 21.”

Taking into consideration the above judgment the State on the question of right to livelihood has failed to recognize the rights of the displaced fishermen community. The State should offer to the affected population special packages for their welfare especially by providing jobs, loans, etc. so that their right to livelihood is respected to certain extent.

The basic needs of all human beings - food, clothing, shelter, health, education, security and self-esteem must be met adequately. Priority must go to these needs. The Supreme Court while recognizing these basic necessities as right to life guaranteed under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution has held in Francis Coralie vs. Union Territory of Delhi [18]. “Right to life means the right to live with human dignity and all that goes along with it, namely, the bear necessaries of life such as adequate nutrition, clothing and shelter over the head and facilities for reading, writing and expressing oneself in diverse forms, freely moving about and mixing and mingling with fellow human beings”.

It is clear from the above court decision that it is the duty of the State to provide basic human necessities not only when the State is displacing a population but generally too.

The Supreme Court has laid down certain guidelines to be followed by the State under a rehabilitation scheme after observing all the factors such as impact of displacement on the livelihood of people, amount of compensation to be paid, providing alternative land, creation of job avenues and providing adequate facilities at the resettled place. It is submitted that the State should create job avenues for dislocated population so that they can compensate their loss of income by the resettlement. Such types of guidelines were laid down by the Supreme Court in Banwasi Seva Ashram vs. State of Uttar Pradesh [19].

“We direct that the following measures to rehabilitate the evictees who were in actual possession of the lands/ houses etc. be taken by NTPC [National Thermal Power Corporation Limited] in collaboration with the State Government [20].

1. One plot of land measuring 60' x 40' to each of the evictee families is distributed for housing purposes through the district administration.

2. Shifting allowance of Rs. 1500 and in addition a lump sum rent of Rs. 3000 towards housing be given to each of the evicteefamilies.

3. Monthly Subsistence allowance equivalent to loss of net income from the acquired land to be determined by the district judge subject to a maximum of Rs. 750 for a period of ten years. The said payment shall not be linked with the employment or any other compensation.

4. The NTPC shall provide facilities in the rehabilitative - area such as pucca roads, pucca drainage system, hand pumps, wells, potable water supply, primary school, health centre, Panchayat Bhawan, electricity connections, bank and SulabhSauchalaya complex [toilets], etc.

5. The NTPC shall also provide hospitals, schools, adult education classes and sports centres for the evictees.”

It cannot be denied that the silence by the state encouraged people to make encroachment on natural resources. The encroachments by the fishermen community were never objected to by the State till late nineties thereby giving implied consent to the possessions of fishermen over a natural resource - Dal Lake. They (fishermen) were enjoying possession without any interference for quite long a time and same was within the knowledge of state. Silence by the state who is the trustee of natural resources resulted into adverse possession over lake. Adverse possession implies possession - commenced in wrong; and maintained against right [21].

Adverse Possession is a possession that is hostile under a claim or colour of title, actual, open, notorious, exclusive and continuous, continued for the required period of time thereby giving an indefeasible right of possession or ownership to the possessor by operation of the limitation of actions [22]. The rule of adverse possession applies equally to government though the period of limitation for acquisition of right against the government is longer [23]. The Limitation Act is biased in favor to the state in one respect only, namely, in requiring a much longer period of adverse possession than in the case of a subject. Otherwise there is no discrimination in the statute between the state and the subject as regards the requisites of adverse possession [24].

In late 1990’s, the then governor of the state, Mr. Jag Mohan Singh reportedly made a public announcement regarding the dismantling of the encroached place (Dhoh) but the actual process of eviction commenced in the year 2000 when the illegal encroachers were served several legal notices, and finally forcibly evicted from the said place. All the structures (about 30 in number) were dismantled and the place was dredged out of the Lake. The urgent steps were taken by the LAWDA under the government sponsored rehabilitation/ resettlement scheme. The main purpose of the scheme was to protect the Dal Lake from encroachment and pollution and also to promote tourism in the State. All the required steps regarding the eviction were taken for public purpose under the Land Acquisition Act [25]. The ‘public purpose’ has been defined in S. 3(g) of the Land Acquisition Act which reads as follows:

“S. 3(g): The expression ‘public purpose’ includes -

1. The provision of land for carrying out any educational, housing, health or slum clearance scheme sponsored by Government or by any authority established by the Government for carrying out any such scheme or with the prior approval by Government.

2. The provision of land for any other scheme of development sponsored by the State or Central Government or with the prior approval of the Government, by a local authority.”

Further, in case of urgency, section 17 provides: “In case of urgency, whenever the Government so directs, the Collector, though no such award has been made, may, on the expiration of fifteen days, from the publication of the notice mentioned in section 9, sub-section (1) [26], take possession of any land needed for public purposes. Such land shall thereupon vest absolutely in the Government, from all encumbrances: Provided that, the Collector shall not take possession of any building or part of a building under this sub-section, without giving to the occupier thereof at least 48 hours notice of his intention to do so, or such longer notice as may be reasonably sufficient, to enable such occupier to remove his movable property from such building without unnecessary inconvenience; and… Provided also that in the case of any land to which, in the opinion of the Government, the provisions of sub-section (1) are applicable, the Government may direct, that the provisions of section 5-A shall not apply, and if it directs, a declaration may be made under section 6 in respect of the land at any time after the publication of the notification under section 4, sub-section (1).”

While proceeding under section 17, the Government is not required to hear the objections from the interested persons (S.5-A) [27] and can directly make the declaration in respect of land under section 6 after the publication of the notice under section 4, sub-section (1).

After following the prescribed steps under Land Acquisition Act, each family was provided an alternative land and was compensated within fifteen days time. The Collector had fixed the dismantling charges/ compensations as per the market value. Apparently the government was successful in fulfilling its obligation of protecting the lake by displacing its occupants and then also providing them rehabilitation.

In the light of Court judgment in Banwasi Seva Ashram vs. State of Uttar Pradesh [28], the Government under the resettlement/ rehabilitation measures to the fishermen evictees failed to provide the facilities of 1) monthly Subsistence allowance equivalent to loss of net income from the acquired land, 2) pucca roads, PanchayatBhawan, Bank, etc., and 3) adult education classes and sports centres for the evictees.

Implications for practice and research

Vivid environmental concerns for the Dal lake and its long term survival have been felt from a long time which can be reflected in the following quote in the book ‘The valley of Kashmir’ by Lawrence published in 1895, “People say that the lake is silting up, and there can be no doubt that as years pass by the deposit of the Arrah river which feeds the Dal must result in the lake becoming even more shallow than it now is... Unless great vigilance is shown the floating gardens of the lake will be extended, and the already narrow waterways to the Mughal gardens will become blocked to boat traffic” [8]. Such disturbing apprehensions have now come true and immediate attention is warranted. Undoubtedly, the eviction of the entire population of occupants from the lake will be an important activity for the management of the lake, followed by the total stoppage of entry of wastewater (whether untreated or apparently treated) into the lake. The above study provides some insights in the eviction exercise and could be strategically extended to the entire lake. According to the AHEC (Roorke) detailed project report prepared for the J&K Lakes and Waterways Development Authority (Oct. 2000), there were 6250 households in the lake located in 105 hamlets/Mohallas [29]. It is claimed that out of these households only 1221 families living in 441 houses/ structures have been resettled but not fully rehabilitated. Notwithstanding that the Government at the behest of the public outcry, concerns & aspirations is trying to rehabilitate the Dal Lake, despite the likely apprehensions that the government might probably lose the proven vote bank if it stirs mass action for Dal evictions, the interest and willingness on the part of the Dal dwellers is not less appreciable. The concerns of the Dal dwellers can be well documented from their suggestions published in a 28 pages booklet ‘Dal lake: retrospect and prospect’ by Dal-dwellers Zamindar Union (undated, printed at Shahanshah Printers, Buchwara Dalgate, Srinagar). An excerpt from the booklet heading “Demands of Dal- Dwellers” reads as:

1. The rate structure set for different kinds of land inside the Dal- Lake be revised so as to make it compatible with the market rate of the land around the Dal-Lake so that the Dal-dwellers whose land holdings are acquired by LAWDA [Lakes & Waterways Development Authority] are re-settled and rehabilitated properly and in an environment friendly manner.

2. To effectuate the process of removal of encroachments and human populations living in the hamlets, the LAWDA/ authorities should acquire entirely the whole hamlet and all land holdings of its habitants together-with all tools of husbandry including small boats etc., as a onetime exercise so that there remains no temptation for the lake dwellers to revert back.

3. A fresh socio-economic survey is conducted for determining the fresh requirements of lake dwellers whose land holdings are sought to be removed. The parameters set in socio-economic survey of 1986 be re-determined/ revised and made compatible with present day requirements.

4. Rehabilitative measures in terms of means of livelihood Commensurating with socio-economic status of Lake Dwellers are provided to the effectees.

5. Adequate compensation is paid to the radh owners whose radhs to the extent of 39 Kanals have been removed from the lake by LAWDA/ authorities in the year 2003 as these radhs were not illegal structures but documented structures as per Revenue records.

6. Lakes and Waterways Development Authority should place each and every information with regard to the acquisition of land holdings of Dal dwellers along with their names whose land and housing structure have been acquired from 1971 till date on its website so that transparency in the official dealings of the LAWDA is ensured and appreciated by public.

7. The LAWDA should compensate the Dal dwellers whose trees have been removed from their proprietary land.

8. The LAWDA should be re-organised at the ministerial and field level in order to weed out the corrupt and unscrupulous officials who covertly allow the illegal constructions to come up in the lake body. Had the Srinagar Municipality been vigilant in the application of municipal laws ever since its establishment to the constructions raised in the lake body or around it, the situation would have been a better one.

The LAWDA authorities have adopted a pick and choose style which suits their fancy but not a comprehensive and result-oriented method for the resettlement and rehabilitation process of Dal-dwellers. The land is being acquired in a piecemeal manner which compels the Dal-dwellers to stay inside Dal-lake and not move out from the Dal Lake permanently.”

The above excerpt reflects the positive attitude and concerns of the lake dwellers towards the protection of the lake. However, further efforts need to be carried out by the management authorities with respect to the economic aspects of the lake. The lake has developed over a long period of time and provides a regular supply of important food commodities - vegetables. Removal of the floating gardens can disturb the balance of the lake besides affecting the economics of the lake dwellers and can also create food crisis in the Srinagar city. Removing floating gardens can also affect the lake aesthetics and wildlife. It is strongly recommended that the lake management authorities should not remove the floating gardens used for growing vegetables. After evicting the occupants and their built structures, they should be allowed to continue growing vegetables with manual boats as the means of transportation. However, use of pesticides, if any, should be closely monitored and further extension of floating gardens or recolonization or stay at the floating gardens should not be allowed. These delicate gardens of Dal Lake can also help in expanding the tourism scenario of the entire Srinagar city and can make Dal Lake a destination of global significance.

“The glory of the lake, the noble pink lily, yields a sweet nut, and a warm, savoury vegetable in its leaf-stem, white, succulent” [8]. The mouth watering delicacy of the Dal - the splendid ‘Nadur’ - may be highly impacted (as is now evidenced by the halting of its growth near STP outfalls in the Hazratbal basin of the lake) by the improper mentality of the people and especially of the money laundering ill advised government by knowingly letting massive flow of the untreated and improperly treated wastewater into the lake which may lead to the erosion of the splendid produce Nelumbo nucifera of the lake forever.

What next?

Working with nature to rehabilitate areas in which undesirable conditions have been created can be more successful and cost-effective than engineering approaches that work against natural processes [1]. After eviction of entire occupant community of Dal Lake, the entry of all kinds of wastewater into the lake should be stopped in its entirety. The lake inflow channel should be maintained from Harwan to the inlet of the settling basin of the lake. Road construction along entire shoreline of the lake, offering an unbreakable view of Dal lake to the visitors, will help in keeping the lake demarcated for all times to come. Next, wait and let nature heals the Dal Lake itself.

Conclusion and Suggestions

A close study of the removed and resettled communities reveals that the resettlement measures taken by the Government are nearly adequate, although some of the facilities which are highlighted from similar court judgments require further improvements. It is seen that such a resettlement has not compromised the basic requirements of the evictees. However, further steps are required to be taken to make the said eviction in consonance with the guidelines of the Supreme Court. The cultivation of Nelumbium (nadru kasht) which the evictees possessed at the time of eviction has not been compensated even after a span of eight years. The alternative lands had been justly provided to the evictees keeping in mind their traditional livelihood occupation. The location of the resettlement site has not totally affected the emotions of the evictees connected with water. The resettlement has brought a good change on the children’s education and therefore, part of the contentment of the evictees is attributed to this factor, although the teacher-student ratio is not justified in the resettled site which is of utmost importance. The access to other sort of works has led to a shift from the traditional occupation to other sort of works among the younger generation. Of late the respondents are facing many problems connected with the well-being, enjoyment and household economics. However, there has been reportedly a negative impact on the monthly income associated with the fishing occupation of the evictees. The evictees claim to have an approximate reduction of 50 per cent in monthly income. Among other factors, however, such a decline in monthly income could be attributable to the overall decline of fish production from the Dal Lake due to pollution, among other things. As the evictees are reportedly suffering from the economic losses, the said evictees could be associated with the Dal lake Restoration work presently undertaken by the government by providing them the labour work (like harvesting of excessively growing macrophytes, etc.) so that their losses are compensated to some extent. Further, the provision of interest-free loan facilities by government should be framed for the overall betterment of the fishermen community to a larger extent. The rearing fish ponds need to be constructed by the Government so that the need on the outside sources is reduced and its benefits are directly added to the economy of the evicted families. Such an act shall have a positive effect in the form of creation of job opportunities to the evictees.

References

- Pike RG, Redding TE, Moore RD, Winker RD, Bladon KD (2010) Compendium of forest hydrology and geomorphology in British Columbia. FORREX Forum for Research and Extension in Natural Resources, Kamloops, B.C., Canada.

- Society for Ecological Restoration International (2004) The SER primer on ecological restoration. Society for Ecological Restoration International, Science and Policy Working Group, Tucson, Arizona, USA.

- Stokes P (1984) Clearwater Lake: study of an acidified lake ecosystem, in Effects of pollutants at the ecosystem level, SCOPE, 229-253.

- Keeley ER, Walters CJ (1994) The British Columbia Watershed Restoration Program: summary of the experimental design, monitoring, and restoration techniques workshop. Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks, and Ministry of Forests, British Columbia, Canada.

- Valiante M (2007) The Law of the Ecosystem: Evolution of Governance in the Great Lakes – St. Lawrence River Basin. Lex Electronica, 12: 1-16.

- Microsoft Encarta Reference Library (2003) “To provide a group or population with a new place to live and transfer it there”.

- Microsoft Encarta Reference Library (2003) Restoration of lost position or reputation: the restoration of somebody’s former position, rank, rights and privileges, influence, or good reputation.

- Lawrence WR (1895) The Valley of Kashmir. Henry Frowde, Oxford University Press, London, UK.

- Consumer Education and Research Centre vs. Unoin Of India, AIR (1995) SC 922, para 24.

- Olga Tellis vs. Bombay Municipal Corp., 1985 SCC(3)548 at 553.

- Olga Tellis vs. Bombay Municipal Corp., 1985 SCC(3)548 at 558.

- National Audubon Society vs. Superior Court of Alpine County, 33 Cal 3d 419.

- Divan S, Rosencranz A (2002) Environmental Law and Policy in India (2ndedn.), Oxford University Press, New Delhi.

- Environment Protection Act (1986), India.

- Water Prevention Act (1974), India.

- Dehradun Quarrying Case (1985) Environmental Protection And Emerging Trends In Judicial Responses.

- Olga Tellis vs. Bombay Municipal Corp., 1985 SCC (3) 548.

- Francis Coralie vs Union Territory of Delhi, 1981 SCR (2) 516.

- Banwasi Seva Ashram vs State Of U.P. And Ors, 1992 AIR 920, 1992 SCR (1) 857.

- Banwasi Seva Ashram vs State Of U.P. And Ors, 1992 AIR 920, 1992 SCR (1) 857, Para 6.

- Krishnaswamy M (1993) Law of Adverse Possession (12th edn.). Library of High Court Srinagar, India.

- Suraj Mal vs. Babu Lal, AIR (1985) Delhi 95 DB.

- Mantharama M (1989) Law of Adverse Possession (2ndedn).

- J & K Land Acquisition Act (1990).

- Section 5A in The Land Acquisition Act, 1894.

- Section 6 of the Land Acquisition Act.

- AIR (1992) SC 920.

- Banwasi Seva Ashram vs State Of U.P. And Ors, 1992 AIR 920, 1992 SCR (1) 857.

- AHEC (2000). Detailed Project Report on Conservation and Management Plan for Dal-Nagin Lake. Alternate Hydro Energy Centre (AHEC), University of Roorke, Roorke.

Relevant Topics

- Civil and Political Rights

- Common Law and Equity

- Conflict of Laws

- Constitutional Rights

- Corporate Law

- Criminal Law

- Cyber Law

- Human Rights Law

- Intellectual Property Law

- International public law

- Judicial Activism

- Jurisprudence

- Justice Studies

- Law

- Law and the Humanities

- Legal Philosophy

- Legal Rights

- Social and Cultural Rights

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 15522

- [From(publication date):

October-2013 - Apr 03, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 10905

- PDF downloads : 4617