Research Article Open Access

Entertainment-Education Using Traditional Folk Song among Female Factory Workers in Lao PDR

Yoshida I1*, Sapkota S2 and Akkhavong K3

1Department of Nursing, Yasuda Women’s University, Hiroshima, Japan

2Sunaulo Parivar Nepal, Implementing partner of Marie Stopes International, Ethiopia

3National Institute of Public Health, Ministry of Health, Lao PDR, Laos

- *Corresponding Author:

- Itsuko Yoshida, RN, PHN, MPH, Ph.D

Department of Nursing, Yasuda Women’s University, Yasuhigashi

Asaminami-ku, Hiroshima, 731-0153, Japan

Tel: +81-82-878-9423

Fax: +81-82-878-9849

E-mail: yoshida-i@yasuda-u.ac.jp

Received date: February 27, 2017; Accepted date: March 04, 2017; Published date: March 10, 2017

Citation: Yoshida I, Sapkota S, Akkhavong K (2017) Entertainment Education Using Traditional Folk Song among Female Factory Workers in Lao PDR. J Community Med Health Educ 7:507. doi:10.4172/2161-0711.1000507

Copyright: © 2017 Yoshida I, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Community Medicine & Health Education

Abstract

Background: Socio-economic development has led to rapid changes in young people's lifestyle and sexual behaviour in Lao PDR. HIV/AIDS education provided at school is not sufficient; therefore, developing effective educational methods is necessary. The purpose of this study was to develop an Entertainment-Education Music Video using 'Lam', Lao traditional folk song (EEMVL) and evaluate its effectiveness.

Methods: Experimental study was conducted at a factory in southern part of Laos. Factory workers received HIV/ AIDS education by watching EEMVL. Fifty one female factory workers were completed semi structured questionnaires at pre and post intervention, and at a two-week follow-up. The questionnaire was included items about knowledge and awareness of HIV/AIDS, self-efficacy of condom use, intention of condom use, positive and negative attitude to people living with HIV/AIDS.

Results: The results showed increased self-efficacy of condom use (p<0.001), reduced negative attitude towards people living with HIV/AIDS (p=0.003) and improved communication on HIV/AIDS information among factory workers (p<0.001) from pre intervention to two-week follow-up. Intention of condom use was increased from pre to post (p=0.017), however, decreased at the two-week follow-up (p=0.02). This decreased intention was due to the participant's understanding of the importance of gaining the skills to protect oneself from HIV infection, and realizing that condoms cannot give 100% protection against HIV infection. Moreover, the participants expressed their desire to preserve Lao culture against HIV/AIDS and to fulfill their responsibility as Lao nationals.

Conclusion: These results suggested that the social modeling behaviour demonstrated in the EEMVL led the audience to improve their health literacy on HIV/AIDS prevention and stimulated interpersonal communication among the participants.

Keywords

Entertainment-Education; Folk song; HIV/AIDS; Lao PDR

Introduction

The Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Laos) is classified as a country with low HIV/AIDS prevalence (0.3% in 2014 among 15-49 year olds in the general population) compared with the neighboring countries of Thailand (1.1%), Myanmar (0.7%), Cambodia (0.6%), and Vietnam (0.5%) [1]. However, the Lao government is aware of risk of an HIV epidemic that could occur for a number of reasons: surrounding countries have high prevalence of the disease, people are expected to be much more mobile in the future both nationally and internationally [2], and these mobilized people will have less access to health care and health education [3]. Although the government has for many years spread the message of safer sex and use of condoms [4], there is a wide disparity between urban and rural areas in access to information and communication. Urban residents have been found to possess more comprehensive knowledge on HIV transmission, for both males (44.5% urban vs. 24.2% rural) and females (37.5% urban vs. 16.4% rural) [5]. There is also a gap between knowledge and practice; one study of unmarried male high school students from urban and rural areas in Laos found 89.3% knew that proper condom use can help prevent HIV yet only 43.9% used condoms regularly [6].

Young people in Laos often engage in risky sexual behaviour even though health education related to HIV/AIDS is provided in primary and secondary school before adolescents become sexually active [4]. Sixty percent of married men reportedly have two or more sexual partners, and only 42.1% of these men always use a condom with their casual partners [7]. Additionally, 47.1% of sexually experienced adolescents in the northern part of the country have two or more sexual partners, but only 48.5% use condoms [8]. Most young people consider negotiating unpaid sex with casual partners to be relatively safe and that condoms are unnecessary [7]. This suggests that providing young people with knowledge is insufficient for protecting them from HIV/AIDS. Most importantly, considering an individual is necessary to remove barriers to safer sex behaviour.

Use of Lao traditional folk songs, Lam, for entertainmenteducation

In countries with a rich and enduring oral tradition, folk media containing morals and heroes serve as an integral part of a child’s nonformal education [9]. Likewise in Laos, traditional folk songs known as lam are passed on and preserve local knowledge from one generation to the next [10]. A previous qualitative study [11] revealed the potential of using lam as a medium for health education. In that study, after listening to lam for HIV/AIDS prevention, the participants were found to have gained knowledge about HIV/AIDS and ideas on how they could act to avoid HIV infection, at both an individual and community level [11]. This learning experience is consistent with the outcomes of entertainment-education (EE), which increases the audience’s knowledge, creates favorable attitudes, and changes behaviour [9]. Another advantage of EE use in HIV/AIDS prevention is its efficacy in stimulating conversation, which brings the taboo topic of HIV/AIDS into public discourse [12]. This conversation enhances people’s sense of collective efficacy, which allows them to work together, using a united voice to solve common problems and improve their lives [13,14]. This phenomenon is also foreseen in countries where talking about sexual issues is largely considered taboo, such as in Laos. A previous study on a peer education program using the EE approach in Laos reported that participants spoke more freely about sexual issues after taking part [15].

To date, in Laos, these educational approaches have not been developed based on social and behavioral science theories, and their intervention effects have not been examined. The present study aimed to develop EE media by using lam, and evaluate the effectiveness of this media for positively changing knowledge and attitudes about HIV/ AIDS and risky behaviors.

Methods

Development of the entertainment-education music video using Lam

The Entertainment-Education Music Video using Lam (EEMVL) was developed from July 2010 to July 2011. Initially, the story for the EEMVL was written by referring to the theoretical framework of Bandura’s social cognitive theory [13,14], using positive and negative role models to encourage the desired behaviour change. The researcher created these models after doing fieldwork that involved interviewing young people in Laos. A Laotian literature scholar then adapted the story to the traditional poetry style. After that, the poem was modified into the singing style of lam loan (a style of lam used in a wide area of Laos) by a singer known as a Molam. The scenes of the story were then depicted through a video taken in Savannakhet Province and the city of Vientiane. Finally, the recorded singer’s voice and the video scenes were combined into a music video CD.

Content of the EEMVL

The main characters are female factory workers aged 18-19 with similar qualities to those of the targeted group in this study. The main character portraying a negative role model enjoys urban life and participates in many activities young Laotians commonly enjoy. The risks of HIV infection that any similar Laotian may face in their normal life are demonstrated through this negatively associated character that, for example, goes to nightclubs, drinks alcohol, and dates an attractive man who has multiple partners. As the tale continues, it is revealed that the boyfriend is HIV-positive, and how she deals with this shocking news is portrayed. Through this portrayal, the story aims to provide the audience with experiences to which they can relate; such as fear of HIV infection, and regretting past behaviour. The other main character, serving as the positive role model, is a young woman who has come from a rural area to work at a factory. Her mother has warned her against having premarital sex. She also values friendship and helps the other main character, who is facing her fear of HIV infection and having to give up her job. The positive character helps her friend return to her workplace and encourages her to go to the clinic to have her HIV status tested. The positive role model sets an example of good attitude and behaviour regarding HIV/AIDS prevention and towards people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). By projecting these social models, the EEMVL aims to give the audience simulated and relatable experiences that will increase their ability to avoid or deal with such problems.

Participants

This project was developed and implemented in collaboration with the National Institute of Public Health’s Ministry of Health, Lao P.D.R. to increase access to health information for hard-to-reach populations. As a study area, we selected Savannakhet Province where 29.3% of all the country’s reported HIV cases originated in 1990–2014 [16]. Participants were recruited from among female workers at a factory for assembling electronic parts for digital cameras. The objectives and outline of the study were explained to all potential participants. Those who volunteered to take part gave oral informed consent. A total of 73 female factory workers consented to and completed the pre-test. Among these, 15 dropped out before and 7 after the intervention, leaving 51 participants who completed the post-test and follow-up test. Reasons for dropping out were cited as change of mind, schedule conflict due to changing work shifts, and resigning from work at the factory.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committee of Hiroshima University (23-1) and the National Ethics Committee for Health Research in Laos (329).

Effectiveness evaluation of the EEMVL

A self-administered questionnaire containing multiple-choice and open-ended questions was used to evaluate the effectiveness of the EEVML intervention at three points in time: pre-test, post-test, and follow-up. The intervention was conducted 2 weeks after the pre-test. Soon after watching the EEMVL, the participants answered the posttest questionnaire. The follow-up test was conducted 2 weeks after the post-test.

Measures

The key outcomes measured were knowledge of HIV/AIDS, awareness of HIV/AIDS, self-efficacy of condom use, intention of condom use, attitudes towards PLWHA, and interpersonal communication.

Knowledge of HIV/AIDS was measured with 10 items which were adapted from the Behavioral Surveillance Surveys [17] regarding to condom use, the routes of transmission such as direct and indirect contact (touching, having sex, sharing toilet with an infected person, and via vector), vertical transmission (mother to child) and iatrogenic transmission (sharing syringe with and transfusing blood from an infected person). The participants corresponded with “Yes”, “No” or “I don’t know” and if the answer was correct it was given a score of 1. The cronbach’s α of this measure were 0.81 (pre-test), 0.70 (post-test) and 0.77 (follow-up).

Awareness of HIV/AIDS was measured with two items, ‘HIV/AIDS is a serious problem in our society’ and ‘young people like us are at risk of getting HIV/AIDS’. The cronbach’s α were 0.70 (pre-test), 0.62 (posttest) and 0.69 (follow-up).

Self-efficacy of condom use was measured with three items, ‘I am able to use condoms to prevent HIV/AIDS’, ‘I am able to talk to my partner about condom use to avoid HIV infection’ and ‘Using condoms to prevent HIV/AIDS is easy for me’. The cronbach’s α were 0.56 (pre-test), 0.74 (post-test) and 0.70 (follow-up).

Intention of condom use, and positive and negative attitude towards PLWHA were measured with single item, ‘I intend to use condoms to prevent HIV/AIDS during 12 months when I have sex’, I’m ready to help and support PLWHA’ and ‘I don’t want to stay with PLWHA because I’m afraid of getting an HIV infection’. Above measurements were based on the participants’ rating of their agreement with statements, and on a 5-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree).

Interpersonal communication was measured to see whether the participants talked about HIV/AIDS with others (family/relatives, coworkers, friends and boyfriend). The participants answered each item with “Yes” or “No”.

Qualitative data were collected by asking open questions such as, ‘What did you learn from this video?’ and ‘What have you talked about or discussed with other people after watching the video?’ In this way the participants described their feelings and ideas in writing.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics for the quantitative data were calculated and examined using SPSS version 22.0 J (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Friedman’s test and McNemar’s test were performed to compare the changes in the outcome measures. The significance level was set at p<0.05, but for multiple comparisons, p<0.017 (0.05/3) was considered statistically significant.

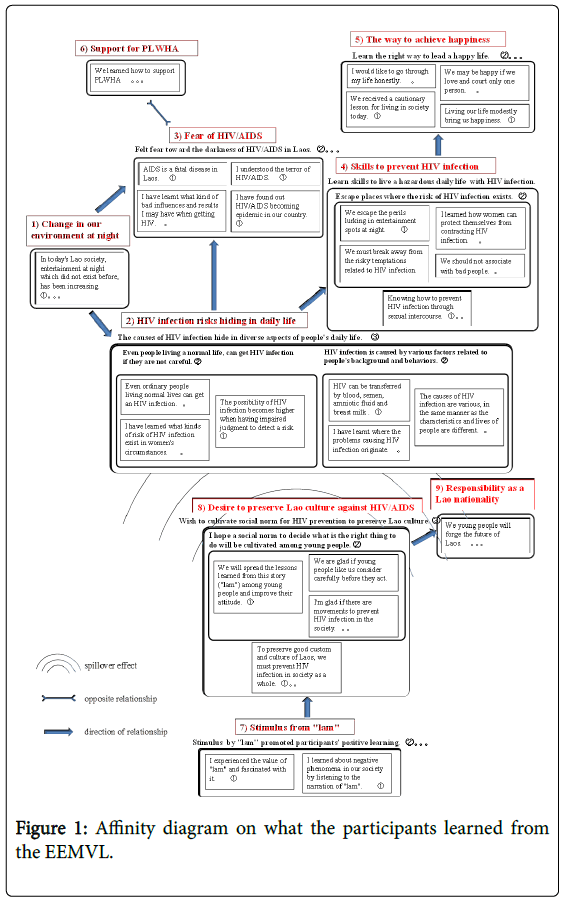

Qualitative data extracted from free description by the participants were analyzed using the KJ method [18] developed by Jiro Kawakita, a Japanese anthropologist, to discover meaningful groups of ideas within raw data. First, the participants’ answers, given in free written response to the open questions at the post-test and follow-up were translated from Laotian to English by an expert on the languages. Second, the researcher extracted sentences from the translated descriptions and wrote them on labels. The labels were ordered based on natural relationships, and headings showing the meaning of each group were created. By using these headings, the ideas of groups were repeatedly gathered until the groupings numbered less than 10. Using the final groupings, affinity diagrams were created (Figures 1,2).

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics

The mean age of the participants was 21.79 years (standard deviation [SD]=4.67). Most (78.4%) were unmarried, living with their family (80.4%) and had never lived away from the family (70.6%). Sixty percent had more than 9 years of formal education and 14.0% had less than 5. As regards earnings, 56.8% earned monthly income of less than 700,000 kip (about US$70). Concerning religion, 98.0% were Buddhists with Lao ethnicity. Twenty-six percent reported having had sex. The average age at first sexual intercourse was 20.08 years (SD=3.12).

Effectiveness of the EEMVL

Friedman’s test revealed significant differences in self-reported selfefficacy of condom use (p<0.001), intention of condom use (p<0.05) and negative attitude towards PLWHA (p<0.01) when comparing the pre-test and follow-up responses. Multiple comparisons showed that the score for self-efficacy of condom use was significantly increased from pre-test to post-test (p<0.001), and from pre-test to follow-up (p<0.001). The score for intention of condom use tended to increase from pre-test to post-test (p=0.017). However, this score decreased from post-test to follow-up (p=0.02). The negative attitude towards PLWHA significantly decreased from pre-test to follow-up (p<0.01) (Table 1).

| Mean rank | p-valuea,1 | Multiple comparisonsb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome measures | pre-test | post-test | follow-up | ||

| Knowledge of HIV/AIDS | 1.88 | 1.98 | 2.14 | 0.206 | - |

| Awareness of HIV/AIDS | 1.98 | 2.08 | 2.05 | 0.398 | - |

| Self-efficacy of condom use | 1.02 | 2.44 | 2.54 | <0.001 | pre to post: p<0.001, pre to follow: p<0.001 |

| Intention of condom use | 1.91 | 2.25 | 1.83 | 0.013 | pre to post: p=0.017, post to follow: p=0.02 |

| Positive attitude to PLWHA | 1.91 | 2.12 | 1.97 | 0.344 | - |

| Negative attitude to PLWHA | 2.27 | 2.03 | 1.70 | 0.003 | pre to follow: p=0.005 |

Note: aSignificant level at p<0.05, bSignificant level at p<0.017, 1Results from Friedman’s test

Table 1: Results of evaluation.

The percentage of interpersonal communication regarding HIV/ AIDS was significantly increased in every category of person: family/ relatives (p=0.001), co-workers (p<0.001), friends (outside of workplace) (p<0.001) and boyfriends (p=0.001) (Table 2).

| Interpersonal communication | Pre-test (%) |

Follow-up (%) |

p-valuea,2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family / relatives | 22.4 | 61.2 | 0.001 |

| Co-workers | 34.7 | 85.7 | <0.001 |

| Friends (out of factory) | 30.6 | 85.7 | <0.001 |

| Boyfriend | 4.1 | 32.7 | 0.001 |

aSignificant level at p<0.05, 2Results from McNemar’s test

Table 2: Increased interpersonal communication.

What participants learned from the EEMVL

From the description of participants’ responses to ‘what you learned from the EEMVL,’ 52 labels were extracted. After integration of the labels, nine groups were identified: 1) Change in our environment at night; 2) HIV infection risk hiding in daily life; 3) Fear of HIV/AIDS; 4) Skills to prevent HIV infection; 5) The way to achieve happiness; 6) Support for PLWHA; 7) Stimulus from lam; 8) Desire to preserve Lao culture against HIV/AIDS; and 9) Responsibility as a Lao national (Figure 1).

After watching the EEMVL, the participants realized that their society has been changing as the country rapidly develops. A number of participants perceived that in present-day Lao society, entertainment at night which did not exist before has been increasing. Such a realization has made them conscious of the risk of HIV infection existing in normal daily life. Some of them said that even people living a normal life can get HIV infection if they are not careful. The participants could imagine the circumstances of PLWHA and seemed to truly fear contracting HIV/AIDS. This fear was shown in the participants’ words such as, ‘AIDS is fatal disease in Laos’ and ‘HIV/ AIDS is becoming an epidemic in our country.’ The participants also learned the importance of gaining skills to live safely in hazardous daily lives. This is shown in: ‘I learned how women can protect themselves against contracting HIV infection.’ The participants then considered how they should live their life and realized that living modestly is the key for success. The comments included, ‘We become happy if we are satisfied with our present circumstances.’ Additionally, the participants ‘learned ways to support PLWHA’ who may present among those around them. They also became aware of the need to preserve Lao culture amid recent social changes related to the risk of HIV infection. Comments included, ‘To effectively preserve the customs and culture of Laos, we must prevent HIV infection in society as a whole.’ This feeling of awareness made the participants express their responsibility, with comments such as ‘We young people will forge the future of Laos.’

Participants’ discussions with others after watching the EEMVL

From the description of participants’ responses to ‘what you have talked/discussed with other people after watching the EEMVL,’ 30 labels were extracted and integrated into eight groups: 1) Fear of HIV/ AIDS; 2) Lack of awareness as a concerned party; 3) Factors increasing risk of HIV infection; 4) Encouragement for PLWHA; 5) Ourselves in society today; 6) Doubt about the effectiveness of condoms; 7) Skills to avoid spreading HIV infection; and 8) Being satisfied with what one has at present (Figure 2).

The participants spoke with their friends and family about their fear of HIV/AIDS. One participant said, ‘We discussed the awfulness of this incurable disease.’ There was an apparent realization that young people lack awareness about the risk of HIV infection that exists in a romantic relationship. Comments included, ‘Young people today are not interested in the risk of HIV infection lurking beneath romance.’ Participants also discussed the increased risk among young people of contracting HIV, for example one said, ‘Drugs and drink numb our mind and body and become causes of HIV infection.’ And they talked about the need to give support to PLWHA: ‘We discussed how we need to encourage and give our hearts to PLWHA.’ The participants then considered themselves in relation to the factors mentioned above and reflected on them. Some participants said they discussed their own position and where they found themselves in society today. They recalled the most important elements for preventing HIV/AIDS, and expressed their doubts about the effectiveness of condom use. Comments included, ‘Using condoms cannot overcome all the risks of HIV infection related to sexual behaviour, even though it is an effective means of prevention.’ At the same time, the participants discussed the relevant skills necessary for an individual to be able to help prevent the HIV/AIDS situation getting worse in Laos. Some participants said that to select appropriate behaviour, they need to consider whether their partner is trustworthy, and avoid going to dangerous places and going out at night. Many also expressed the importance of being content with what one has. Comments included, ‘It is important to love one’s family and be satisfied about the present.’

Discussion

This study evaluated the effectiveness of the developed EEMVL for building and enhancing knowledge and attitudes about HIV/AIDS and risky behaviour. Quantitative data revealed that the participants’ selfefficacy of condom use increased after the EEMVL intervention. This finding is consistent with earlier research [12,19] where entertainment drama improved viewers’ self-efficacy. According to social cognitive theory [13,14], observing punishing outcomes can create negative outcome expectations that serve to disincentives similar courses of action. In the EEMVL, the punished behaviors were portrayed through a negative role model who was afraid of HIV infection because she had not been careful about using condoms when having sex with her boyfriend, who had multiple sex partners. This model negatively reinforced the value of that behaviour in the participants’ minds, which resultantly increased condom use.

Our findings revealed that the intention to use condoms among the participants increased soon after the intervention. Previous studies [20,21] which showed that an effective EE program increased the audience’s intention echoed this finding. In contrast, however, in this study there was a tendency for the reported intention score to decrease from post-test to follow-up. Qualitative data, wherein the participants expressed doubts about the security and efficacy of using condoms to prevent HIV prevention may help explain this. Participants also expressed that to prevent HIV infection it was necessary not only to use condoms but also to have other important skills, such as considering if a partner and the places a couple goes are safe, avoiding HIV infection risks, and behaving appropriately. This discussion held among the participants partly revealed the reasons for the decreased intent to use condoms which were seen from post-test to follow-up.

The EEMVL served to reduce negative attitudes towards PLWHA. This quantitative result is supported by qualitative results showing that support and encouragement for PLWHA are needed. In the EEMVL, the positive role model encourages the friend who may have an HIV infection, tries to help her return to her workplace, and encourages her to have her HIV status tested at a clinic. This model may be considered favorable, particularly in Lao society where people have a high degree of morality and a philoso+phy those values helping one another [22]. Thus, the participants could relate to the experiences through positive models and these reinforced the value of certain attitudes towards PLWHA.

Qualitative data showed that the lam was a stimulating experience for participants, and this made their learning experience positive. Such stimulation can be tied to a desire to preserve Lao culture against HIV/ AIDS and draws on participants’ responsibility as Lao nationals. This finding is consistent with our earlier study [11] wherein characteristics of lam represented by Lao people’s oral tradition promoted positive reactions from the audience. According to Chapman [23,24], lam is construed as a metaphor for Lao-ness and is connected to the Lao identity. Therefore, a stimulation using lam made the participants conscious of their cultural identity and impelled their desire to preserve their culture. McMellon [25] reported that Lao youth consider that doing the right thing is linked with a clear sense of national identity and pride in being Lao. This sense might have led the participants to express their desire to cultivate a social environment in which community members help each other to prevent HIV infection, while at the same time preserving the Lao culture.

The results of interpersonal communication on HIV/AIDS information showed that participants talked about HIV/AIDS with others, such as family members, co-workers, friends and boyfriends or husbands, after the intervention. This finding is consistent with past research that showed the EE intervention encouraged the audience to discuss the media itself [19,26-28]. This conversation may be induced by the EEMVL scene in which the main characters discuss HIV/AIDS and ways of dealing with the fear of being infected. A previous study [27] showed that the EE program provides social scripts for difficult interpersonal discussions by fostering identification with characters who model this behaviour. Kidd et al. [29] also stated that traditional folk media create and promote horizontal communication or peer learning. Incorporating this folk media in the EEMVL may enhance peer communication among an audience, yielding an effect on interpersonal communication. This effect may be useful in many Asian countries, such as Laos, whose cultures are relatively more collectivistic [30].

In addition to improved peer communication, the conversations among the participants and others showed that the participants were aware of the necessary skills for preventing HIV infection. According to previous study in India [31], involvement with the characters in the story often prompts audience members to initiate discussion on socially desirable behaviour. The results of the present study suggested that the socially desirable behaviors that participants perceived were gaining necessary skills to prevent HIV infection, such as considering a partner’s trustworthiness and a place’s safety, avoiding dangers, adopting proper behaviour and using condoms. Through the participants’ discussions, they may be persuaded to adopt these behaviors. These findings revealed that the EEMVL may boost individuals’ skills in preventing HIV infection through creation of a social learning environment in which people learn from one another, and through persuading the audience to adopt normative behaviors.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, the results estimated the effectiveness of the EEMVL in the specific target group—female factory workers. Therefore, potential generalization of the study’s outcomes is limited. This appears mainly due to the results found in a previous study of entertainment television programs [21], which demonstrated a gender-based difference in intervention effects. For example, a dramatic narrative decreased male participants’ safer sex intentions. Such a difference in the effectiveness of the intervention in line with socio-demographic characteristics may exist in Laos. Additionally, gender roles and power relations in sexual interactions could not be considered in this study. Therefore, for future study, comparing the effects of the EEMVL across the sexes and different population types is necessary to establish the most effective way to apply the EEMVL. Second, this study was conducted without setting a comparison group. Future studies therefore should compare the degree of effectiveness with other educational media. This study neither examined the outcomes beyond the 2 weeks of the follow-up period nor assessed likely maintenance of those outcomes over a longer period. We therefore recommend that future studies incorporate a longer follow-up period and examine behavioral and social changes while assessing the impact of the EEMVL.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the participants’ valuable contribution to this study and thank Douangdeuane Viravong for her effort in writing traditional poems for developing the EEMVL. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 16K12358.

References

- World Health Organization (2014) Global health observatory data repository. Prevalence of HIV among adults aged 15 to 49, estimates by country (2000-2014).

- Molland S (2010) ‘The Perfect business’: human trafficking and lao-thai cross-border migration. Development Change 41: 831-855.

- Wolffers I, Fernandez I, Verghis S, Vink M (2002) Sexual behavior and vulnerability of migrant workers for HIV infection. Culture, Health and Sexuality 4: 459-473.

- Lao PDR (2006) National strategic and action plan on HIV/AIDS/STI 2006-2010. Committee for the Control of AIDS, National Vientiane.

- Ministry of Health and Lao Statistic Bureau (2012) Lao social indicator survey 2011-2012.

- Thanavanh B, Harun-Or-Rashid M, Kasuya H, Sakamoto J (2013) Knowledge, attitude and practices regarding HIV/AIDS among male high school students in Lao People’s Democratic Republic. J Int AIDS Soc 16: 17387.

- Toole MJ, Coghlan B, Xeuatvongsa A, Holmes WR, Pheualavong S, et al. (2006) Understanding male sexual behaviour in planning HIV prevention programmes: lessons from Laos, a low prevalence country. Sex Transm Infect 82: 135-138.

- Sychareun V, Thomsen S, Chaleunvong K, Faxelid E (2013) Risk perception of STIs/HIV and sexual risk behaviours among sexually experienced adolescents in the Northern part of Lao PDR. BMC Public Health 13: 1126.

- Singhal A, Rogers EM (1999) Entertainment-Education: A communication strategy for social change. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, New Jersey.

- Bernard-Johnston J (1993) Singing the lives of the Buddha: Lao folk opera as an educational medium (Doctoral dissertation).

- Yoshida I, Kobayashi T, Sapkota S, Akkhavong K (2012) Evaluating educational media using traditional folk song (“Lam”) in Laos: a health message combined with oral tradition. Health Promot Int 27: 52-62.

- Singhal A, Rogers EM (2006) Combating AIDS: Communication strategies in action. Sage Publications, New Delhi, India.

- Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall, New Jersey, USA.

- Bandura (2004) Social cognitive theory for personal and social change by enabling media. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, New Jersey, USA, pp: 75-96.

- Hoy D, Southavilay K, Chanlivong N, Phimphachanh C, Douangphachanh V, et al. (2008) Building capacity and community resilience to HIV: A project designed, implemented, and evaluated by young Lao people. Glob Public Health 3: 47-61.

- Ministry of Health (2015) Lao PDR country progress report.

- Amon J, Brown T, Hogle J, MacNeil J, Magnani R, et al. (2000) Behavioral surveillance surveys: Guidelines for repeated behavioral surveys in populations at risk of HIV.

- Kawakita J(1986) KJ-method: let chaos tell. Chuoukouronsha, Tokyo, Japan.

- Moyer-Guse E, Chung AH, Jain P (2011) Identification with characters and discussion of taboo topics after exposure to entertainment narrative about sexual health. J Commun 61: 387-406.

- Naar-King S, Rongkavilit C, Wang B, Wright K, Chuenyam T, et al. (2008) Transtheoretical model and risky sexual behavior in HIV+youth in Thailand. AIDS Care 20: 198-204.

- Moyer-Guse E, Nabi RL (2010) Explaining the effects of narrative in an entertainment television program: Overcoming resistance to persuasion. Human Commun Res 36: 26-52.

- Hayashi Y (2000) Religion and cultural transition in Laotian society. Kyoto University Press, Kyoto, Japan.

- Chapman A (2004) Music and digital media across the Lao diaspora. Asia Pacific J Anthropology 5: 129-144.

- Chapman A (2005) Breath and bamboo: Diasporic Lao identity and the Lao mouth-organ. J Intercultural Study 26: 5-20.

- McMellon C (2013) Learning the Scripts: An exploration of the shared ways in which young Lao volunteers in Vientiane understand happiness. Health, Culture Soc 5: 118-134.

- Vaughan PW, Rogers EM (2000) A staged model of communication effects: evidence from an entertainment-education radio soap opera in Tanzania. J Health Commun 5: 203-227.

- Love GD, Mouttapa M, Tanjasiri SP (2009) Everybody’s talking: using entertainment-education video to reduce barriers to discussion of cervical cancer screening among Thai women. Health Educ Res 24: 829-838.

- Khalil GE, Rintamaki LS (2014) A televised entertainment-education drama to promote positive discussion about organ donation. Health Educ Res 29: 284-296.

- Kidd R, Byram M (1978) The performing art and community education in Botswana. Community Dev J 13: 170-178.

- Rogers E, Steinfatt TM (1999) Intercultural communication. Waveland Press, Illinois, USA.

- Singhal A, Sharma D, Papa MJ, Witte K (2004) Air cover and ground mobilization: integrating entertainment-education broadcasts with community listening and service delivery in India. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, New Jersey, USA.

Relevant Topics

- Addiction

- Adolescence

- Children Care

- Communicable Diseases

- Community Occupational Medicine

- Disorders and Treatments

- Education

- Infections

- Mental Health Education

- Mortality Rate

- Nutrition Education

- Occupational Therapy Education

- Population Health

- Prevalence

- Sexual Violence

- Social & Preventive Medicine

- Women's Healthcare

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 4353

- [From(publication date):

April-2017 - Nov 23, 2024] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 3687

- PDF downloads : 666