Effects of Numerous Anthropogenic Disturbances and Forest restoration

Received: 27-Jul-2022 / Manuscript No. jescc-22-72243 / Editor assigned: 29-Jul-2022 / PreQC No. jescc-22-72243 (PQ) / Reviewed: 12-Aug-2022 / QC No. jescc-22-72243 / Revised: 16-Aug-2022 / Manuscript No. jescc-22-72243 (R) / Accepted Date: 16-Aug-2022 / Published Date: 23-Aug-2022 DOI: 10.4172/2157-7617.1000634

Abstract

This study aimed at assessing the role of enrichment planting on population structure, diversity and canopy cover in open gaps in an indigenous tropical forest. Five selected indigenous tree species namely Croton megalocarpus, Fagara microphylla, Markhamia lutea, Newtonia buchananii and Vitex keniensis were investigated. Systematic random sampling was conducted on two sites namely, the enriched and control sites where five study plots of 100m by 20m each were established.

Keywords

Canopy cover; Enrichment planting; Open gaps

Introduction

Trees are the drivers that promote natural mechanisms of forest regeneration and their populations help to sustain biodiversity in tropical ecosystems [1]. Their uses include maintenance of forest structure, water purification, recharge of rivers, biodiversity reservoirs as well as promoting habitat restoration [2]. Trees are also the most effective resources in carbon sequestration and forests are the safest natural and affordable infrastructure for capturing and storing this carbon [3]. Tropical forests have high rates of biomass productivity and the potential to assimilate and store relatively large amounts of carbon. Most of the carbon in trees and shrubs is accumulated in above-ground biomass and half of this is taken as carbon stock. Above-ground carbon stock is 50% of the total vegetation biomass made up by carbon while below-ground biomass is considered a fraction that takes about 25-30% of above-ground biomass.

Conservationists and policy makers all over the world are increasingly recognizing that a transformation of the forest industry is fundamental for socio-economic development. Besides biomass accumulation and carbon sequestration, trees in tropical forests promote plant biodiversity and structure in terms of species richness and evenness. Hence increasing the number of indigenous species through restocking of most logged species helps in promoting and maintaining the global forest industry. This is achieved through restoration strategies that are more capable of sustaining high species richness and diversity while still promoting good forest yields and providing multiple ecosystem services.

Tropical deforestation has remained a major driver of global warming. Deforested areas have significantly lost productivity due to unsustainably destructive tree harvesting practices. According to UNEP (2014), tropical deforestation accounts for 0.6–1.5 Gtc (Gigatonnes of carbon) per annum of which 6-14% of this results from anthropogenic activities. Such activities vary and include commercial and smallholder agriculture, mining, road construction, infrastructural development, logging and defaunation.

Many studies have been carried out and recommended various recovery strategies to alleviate deforestation in tropical forests. Improved land use, streamlined governance, community participation and sustainable forest management will significantly reduce tropical deforestation. Curbing forest conversion for commercial agriculture has also been identified as an efficient measure to mitigate tropical deforestation. In addition, reforestation has been reported as a good alternative with the potential to rehabilitate deforested soils and as well promote and conserve forest biodiversity. Moreover, enrichment planting with valuable indigenous trees has been suggested as a sustainable recovery measure to curb deforestation.

Enrichment planting refers to a set of techniques used to raise or restock trees especially in logged over forests. Selective logging of important timber species greatly reduces the canopy cover, modifies forest composition, structure and undermines their regenerative capacity. Enrichment planting with valuable indigenous tree species favors both the long term recovery of forests by promoting their populations and biodiversity particularly in logged over areas. The practice assists to recover indigenous tree densities beyond existing natural stands. Species mixtures of mostly native trees during enrichment improves the conservation of water resources, soil, aquatic life, wildlife and the maintenance of environmental equilibrium as well as combating pest-induced damages. Besides, the use of native trees also contributes to the conservation of native flora and fauna.

Forest restoration through enrichment planting particularly in open gaps aims at the preservation and development of natural resources of water, air, soil and all components of fauna and flora. Knowledge on open gaps (openings on the forest canopy) and canopy cover play a significant role in sustainable forest management and the utilization of tropical forests. Some plants especially of tropical nature will thrive best in the over-story while others will survive just beneath the canopy. Gaps create variation in light regimes, diversify niches and forest microclimates. According to Putz and Romero 2015, canopy closure accelerates the recovery of a forest which sustains its structure and productive value. This helps to mitigate encroachment pressure on such a forest thereby promoting recovery upon disturbance. Disturbance has been reported to result in immense habitat loss thereby affecting species richness and genetic diversity in tropical ecosystems [3]. Open gaps correlate with many abiotic factors e.g., light availability, soil temperature, air vapor, nutrient and moisture content and biotic factors such as humus quality, micro-flora and microbial-fauna; which all in turn influence tree seedling establishment and development, floristic composition and structure. Hence, restoration of forests with high value native trees and species mixtures in open gaps allows for the provision of habitat connectivity, biodiversity and ecosystem function.

This study contributes to the existing knowledge on tree planting by providing a broad synthesis of the previously published information regarding enrichment planting in Mount Kenya forest. It aims at guiding the establishment, development and sustainable use of the forest. Consequently the study sought to assess the role of enrichment planting using indigenous trees on population structure, diversity and canopy cover in open gaps in Mount Kenya forest.

Materials and Methods

Study Location

The study was carried out in Meru South within the larger Chuka forest, East of Mount Kenya (Figure 1).

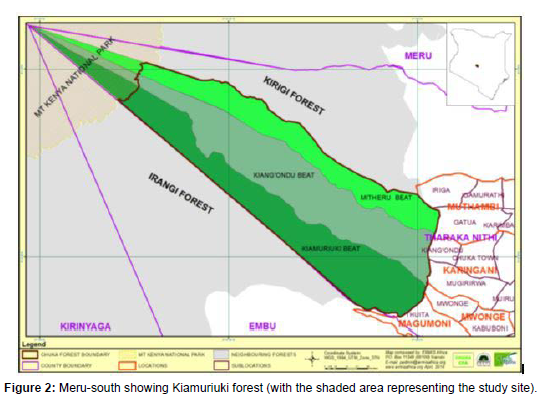

The elevation ranges from 500 to 2,200 m resulting in a wide range of climatic conditions within the study site. Rainfall pattern ranges from 900 mm in the north to 2300 mm south with the highest rainfall between 2700 and 3100 m. This research was conducted on the eastern slopes of Mount Kenya Forest. The specific study was on Kiamuriuki forest (Figure 2) that covered approximately 20,000 m2 (0.02 km2) and is part of the larger Mount Kenya forest reserve. The study sites are located at longitudes 37 18’ 37” and 28’33” East and latitude 00 07’23” and 00 26’19” South.

Study species

A reconnaissance study was carried out in the study sites before the study commenced to assess the structure, diversity and canopy cover status of the tree species and identify the appropriate species for the study. The preliminary visit established that a number of anthropogenic activities driven by the need for economic gains had taken place on the study site. It revealed that logging, charcoal burning and cultivation were common and heavily impacted on tree structure, diversity and canopy coverage on the study site. It further established that out of 17,603 ha of the indigenous forest 1268 ha were severely logged, coupled with the disappearance of indigenous trees between the years 2010-2018. The survey identified such indigenous tree species to include Newtonia buchananii, Markhamia lutea, Vitex keniensis, Croton megalocarpus and Fagara microphylla. The five tree species were hence selected for the study and identified with the help of the forest inventory obtained from the County forest office Meru South District Environment Action Plan 2010. The five species have in the past been reported to typically colonize disturbed areas.

Data collection

On the established sample plots seedlings, saplings and adult trees were counted and recorded. In this study seedlings were categorized as plants ≥ 5.0 cm in height, saplings 0.5-2 m while adults were those greater than 2 m tall. This height classification has previously been applied in a similar study conducted by Lewis, (2013). Stem diameter at breast height (DBH ≥ 1.35 m above the ground) less than 10 cm for all woody species was measured and recorded. Stem diameter at breast height (DBH ≥ 1.35 m above the ground) greater than 10 cm for all woody trees was also measured and recorded. The DBH was measured using a DBH tape and a tree caliper to the nearest centimeter. The tree caliper was preferred where DBH was less than 10 cm as it was easier to use than the tape to measure small tree diameters Misgana, 2014; Park & Height measurements for trees ≤5 m were done using a Suunto clinometer, recorded and approximated in cases where topography and canopy conditions were not suitable. The same measurement was performed for trees with height greater than 5 m. This technique has been used with success elsewhere. Diversity was enumerated for species richness using the Shannon-Wiener index [4]. Canopy cover was measured and estimated applying the ground measurement technique using the line intercept method as suggested in. All the study species encountered in the plots were recorded by their scientific names identified in the forest inventory as suggested in Chowdhury.

Data analysis

Population structure analysis

Population structure was analyzed using parameters of density, DBH and height classes of all the sampled trees. Density was calculated using the overall number of trees counted total numbers of seedlings, saplings and adults across the study sites. DBH (cm) was recognized in the enriched and control sites using five diameter classes (≤10, 11- 20, 21-30, and 31-40 and ≥ 41). Four height classes (in meters) were recognized in the enriched and control sites (≤5, 6-10, 11-15 and ≥16). In other studies, such DBH and height size classes have been reported to be useful in analyzing population structure of forest vegetation [5]. The values obtained for tree density, DBH and height classes were subjected to ANOVA (analysis of variance) in order to compare population structure between the enriched and control sites. ANOVA tests were performed using Excel (MS Excel 2013) to compare the differences between the means for the enriched (P1-P5) and control (P6-P10) sites. The test was preferred because the analysis involved more than two means for each parameter that was under investigation. In addition data per plot on density, DBH and height was normally distributed. To check for normality, data was first subjected to Excel normality tests for verification and consequent analysis. The histograms (bars) obtained confirmed the data to exhibit normal distribution hence no transformation was performed. This study estimated angular canopy cover which is the vertical projection of tree crown onto a horizontal ground [6-7]. To determine percentage canopy cover, the line-intercept crown cover method was used which is primarily ground-based. The method measures canopy cover by recording horizontal distances covered by live crowns along a line-transect after which percentage canopy cover is calculated as a ratio of the length of the transect covered by canopy and the full length of the transect.

On both enriched and control sites, canopy cover data were collected and recorded for individual tree species relative to vertical canopy layers. Canopy cover was measured and recorded for each species of live trees ≥1.4 m tall along horizontal transects using a tape measure. For every species and canopy layer, the distance along each transect line where the crown first intercepts the line to the point where the crown last intercepts the line was recorded to the nearest distance in meters (m), where the Suunto clinometer was used to verify crown interception directly overhead. Projection of individual cover elements by species and layer was done using transect distance (line segment) measurements to estimate total crown distance over each transect. The proportion of transect lengths that were intercepted by crowns was the ground-estimated canopy cover and ranged from 0 to 100% (transect length =100 meters). Canopy cover was calculated as the proportion of the total points intersected by species cover. Canopy cover was estimated (as a percentage) by summing tree crown areas by each species for the enriched and control sites.

The line-intercept crown cover technique was particularly preferred as it is faster, cheaper and useful when technical capacities to use other methods like digital imaging are limited. According to Paletto and Tosi (2009), this technique gives the most reliable estimates of vertical canopy cover in forested tree stands. Studies conducted by Korhonen 2006 reported other techniques such as digital photographs, ocular estimation and spherical densitometers to have larger variances and may be seriously biased. ANOVA was conducted to compare the differences between the means for canopy cover of indigenous trees between the enriched and control site. Data was tested for normality using the Excel normality test, confirmed to be normally distributed and therefore did not require any transformation.

Results and Discussion

A total of 439 trees were sampled, 259 on the enriched and 180 on the control site. ANOVA was performed to compare the means between the enriched and control site.

Population structure

Overall tree density

There was no significant difference in mean density between the enriched and control site; F (9, 4) =1.19, p=0.33. Overall tree density was higher on the enriched site than that on the control site. Most forest plants thrive well in areas with adequate light and temperature conditions [8]. In such environments microbial and enzyme activity in the soil increases on which litter decomposes rapidly which significantly improve soil fertility thereby supporting a higher plant density? Such site conditions could have favored the high densities of trees on the enriched site. Plant survival in the understory is also greatly influenced by solar radiation and moisture penetration, which are latter affected by canopy openness. A similar study conducted by Shono reported that dense planting of large numbers of native tree species in open gaps significantly raised their populations. This implies that appropriate canopy openness sharply increases plant density in the understory. This could probably explain why overall tree density on the enriched site was higher than that on the control site. As however highlighted by, disturbance through such activities as logging is important in maintaining community composition and determining population dynamics in tropical and extra tropical forests. A statistical analysis revealed no significant difference in mean density of seedlings between the enriched and control site; F (9, 4) =0.64, p=0.75.

Seedling emergence increases with canopy openness. Their growth and survival in the understory is significantly affected by solar radiation, transmittance and moisture which are in turn influenced by the openness of a canopy. Furthermore, a study conducted by Bu indicated that increased light intensities after selective logging provide new micro-sites for trees to successfully grow and establish. They further argue that logging stimulates seedling establishment and some of the remnant stumps to resprout. Their findings are in agreement with the results of this study which was conducted in a logged over forest in open gaps where light intensity was presumably adequate. Established that regular cutting of competing vegetation greatly improves the performance of planted seedlings in open gaps that have developed from logging. There is a positive impact in density on forest disturbance through logging on seedlings. This finding concurs with results in this study which has established that the density of seedlings is generally higher than that of adults in open gaps. demonstrated that when seedlings of high value indigenous tree species are introduced in open gaps, they achieve high growth and survival rate suggesting that enrichment planting markedly restores graded tropical lands. According to Chazdon, shade-tolerant species are gradually recruited to a forest community and grow into saplings and adults over time.

Density of saplings

There was significant difference in mean sapling density between the enriched and control sites; F (9, 4) =2.16, p=0.04 Saplings of two hickory species in a study conducted by Ramage consistently exhibited a reduction in growth rates when large conspecifics were nearby. Their results from growth‐based point pattern analyses generally concur with results in this study. Larger conspecific neighbors inhibit plant performance due to intraspecific competition, thereby impacting negatively on younger plants. This observation could probably explain the less sapling density on the control site that harbored larger trees than those observed on the enriched site with smaller sized trees. Moreover, according to Lindenmayer & Laurance 2017, smaller trees are more sensitive to competition and more susceptible to numerous natural enemies compared to larger individuals. This observation could largely be driven by a general reaction of plants to light availability and intensity in which larger trees cause shading to the more light demanding saplings.

Enrichment planting survival rates may be improved by planting species in sites that optimize their growth and survival based on their known ecology, a strategy referred to as species-site matching. Ecological site variability’s of nutrition, moisture, elevation and biotic factors are crucial in the survivorship from seedling, sapling and adult stages of tropical species. This strategy could probably have favored more saplings on the enriched than the control site. This study is in agreement with a study conducted by Bello who concluded that different species respond differently to site conditions and at a relatively fine scale.

Intensive maintenance after planting improves the survival rates of tree saplings. It could therefore be possible that tending for the trees upon enrichment planting on the enriched site in this study may have achieved the better survival of saplings hence their increased density. This is in comparison to the untended control site on which no maintenance was instituted.

Conclusion

The present study reveals that numerous anthropogenic disturbances, mainly logging result in the disruption of structure, reduced species diversity and overall canopy coverage which are major forest components. The study has further established that by promoting the density of desired tree species, enrichment planting can markedly increase the productivity of tropical forests. Overall tree density was found to be higher after enriching open gaps in the forest on which logging had taken place. However, areas that were left out of the enrichment regime exhibited a remarkably lower density of trees in the forest. Seedlings and saplings formed the majority of trees compared to the low number of adults on both the enriched and control sites. Based on these observations, this study suggests a mixture of indigenous tree species that exhibit close structural and functional traits during enrichment planting to encourage forest heterogeneity hence an ecological balance on the structure and increased forest diversity [9].

Enrichment planting in this study substantially increases the structural and diversity value of Mount Kenya forest hence should be considered by policy-makers, conservation managers and other promoters interested in the sustainable use and the long-term value of the forest. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that where harvests of high-value indigenous trees and dense forest cover persist, enrichment planting in logging gaps has positively impacted by increasing stocks of valuable tree species [10]. However, this study primarily focused on enrichment planting in open gaps and that the present findings were based on only five indigenous tree species. The study therefore suggests that alongside enrichment planting, a combination of other silvicultural techniques (including assisted natural regeneration) are necessary to improve the structure, diversity and canopy cover of indigenous trees in Mount Kenya forest. Hence, further research is necessary to assess different strategies and approaches that should be tested to restore and recover logged forests as well as achieve optimal ecological benefits from enrichment planting.

Funding: There is no Funding for this article.

References

- Alexander JM, Kueffer C, Daehler CC (2011) Assembly of Nonnative and Tree Biomass in Deferent Restoration Systems in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Forests 10(7):5-88.

- Ali Z, Bibi F, Shelly SY (2011) Comparative avian faunal diversity of Jiwani coastal wetlands and taunsa barrage wildlife sanctuary, Pakistan. J Anim Plant Sci, 21(2):381-387

- Barton DN, Benjamin T, Cerdán CR (2016) Assessing ecosystem services from multifunctional trees in pastures using Bayesian belief networks. Ecosystem Services 165-174.

- Hosonuma N, Herold M, De Sy V (2012) An assessment of deforestation and forest degradation drivers in developing countries. Environ Res Lett 1-12.

- de Andrade RB, Balch JK, Parsons AL (2017) Scenarios in tropical forest degradation: carbon stock trajectories for REDD+. Carbon Balance Manag 1-7.

- Ali Z, Bibi F, Shelly SY (2011) Comparative avian faunal diversity of Jiwani coastal wetlands and taunsa barrage wildlife sanctuary, Pakistan. J Anim Plant Sci 381-387.

- Poorter L, van der Sande MT, Thompson J (2015) Diversity enhances carbon storage in tropical forests. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 24:1314-1328.

- Bibi F, Ali Z (2013) Measurement of diversity indices of avian communities at Taunsa Barrage Wildlife Sanctuary, Pakistan. J Anim Plant Sci 469-474.

- Fiala AC, Garman SL, Gray AN (2006) Comparison of five canopy cover estimation techniques in the western Oregon Cascades. For Ecol Manag 232: 188-197.

- Jacobs M (2012) The tropical rain forest: A first encounter. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Chazdon R.L, Guariguata M. R (2016) Natural regeneration as a tool for large scale forest restoration in the tropics: prospects and challenges. Biotropica 716-730.

- Keefe K, Alavalapati JAA, Pinheiro C (2012) Is enrichment planting worth its costs? A financial cost–benefit analysis. For Policy Econ 10-16.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Citation: Cope A (2022) Effects of Numerous Anthropogenic Disturbances and Forest restoration. J Earth Sci Clim Change, 13: 634. DOI: 10.4172/2157-7617.1000634

Copyright: © 2022 Cope A. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 1894

- [From(publication date): 0-2022 - Apr 03, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1548

- PDF downloads: 346