Effects of Mental Health Exposure Factors on the Prevalence of Postpartum Depression: A Nevada Population-Based Study

Received: 31-Oct-2018 / Accepted Date: 04-Jan-2019 / Published Date: 11-Jan-2019 DOI: 10.4172/2376-127X.1000401

Abstract

Background: Postpartum Depression (PPD) is a common and critical complication for mothers after delivery. The present study aims to analyze the relationship between key exposures and the outcome of PPD in Nevada mothers.

Methods: Data (n=3,579) was gathered through the 2015-2016 Nevada Baby Birth Evaluation and Assessment of Risk Survey (BEARS), response rate 31.1%. This study focused on whether mothers who were diagnosed with PPD had 1) a history of pre-pregnancy depression 2) experienced Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) 3) used cannabis and 4) had a home healthcare worker visit during pregnancy. Weighted multiple logistic regressions were conducted using SAS 9.4.

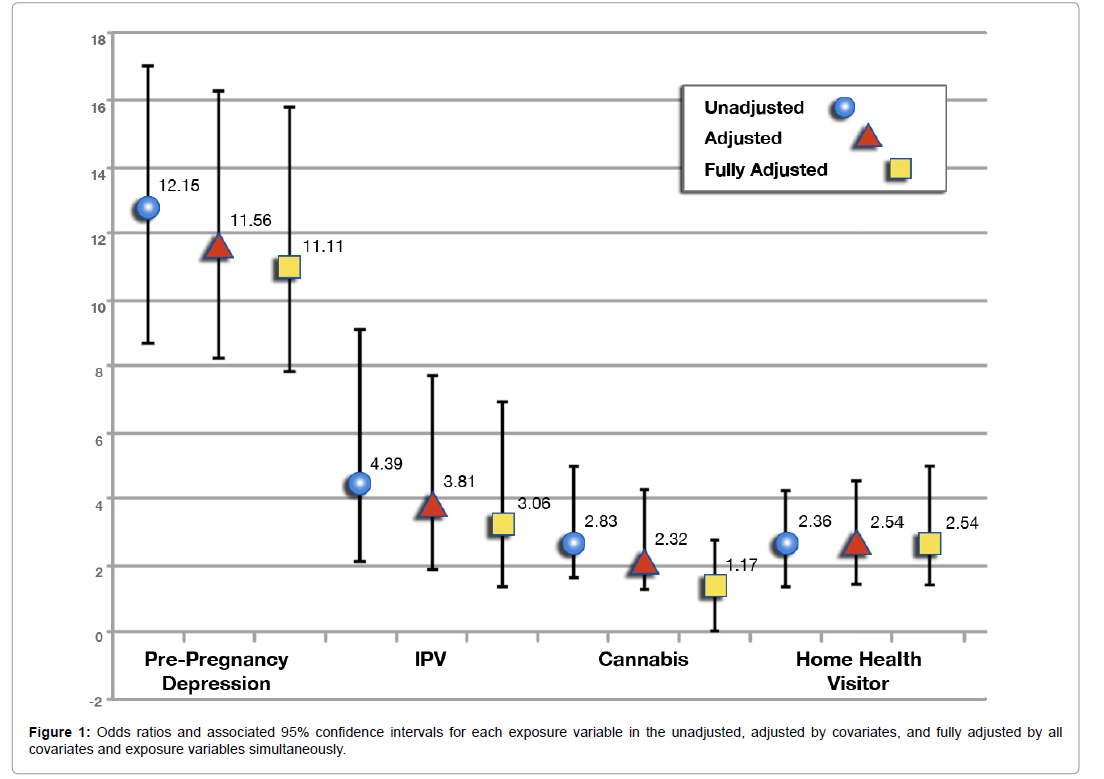

Results: There are 8.84% (n=286) mothers who reported a PPD diagnosis since delivering their new baby. After adjusting simultaneously for all other factors, pre-pregnancy depression, intimate partner violence before and/or during pregnancy and home healthcare visitor remained significant with aORs of 11.11 (p-value ≤ 0.01, 95% CI=7.81, 15.81); 3.06 (p-value ≤ 0.01, 95% CI=1.35, 6.92) and 2.54 (p-value ≤ 0.01, 95% CI=1.40, 4.95) respectively.

Conclusion: Mental and maternal healthcare must adjust care for mothers who report these exposures. PPD is a negative maternal health outcome and must be a prevention priority in public health.

Overview: The present study will explore data on several key exposure factors relating to postpartum depression in Nevada mothers utilizing data collected from the 2015-2016 Baby Birth Evaluation and Assessment of Risk Survey (BEARS). Results from this study can be used to expand and improve upon current postpartum depression screening and treatment, in both prenatal and postpartum care settings.

Keywords: Postpartum depression; Pregnancy; Mental health; Population-based; Epidemiology; Maternal health; Prenatal health

Background

Depression is a multifaceted disease with many different precursors, symptoms, types and clinical presentations. A particularly vulnerable group is pregnant and perinatal women. Postpartum Depression (PPD) is defined as a major depressive disorder [1]. PPD is included in the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5). It is considered to be an incapacitating but highly treatable mental disorder. PPD is one of the most regularly seen complications associated with pregnancy and bearing children [2]. PPD affects 21.9% of mothers [3]. PPD is defined as starting within one month postpartum, however, many women begin to experience depressive symptoms during pregnancy and some occurring after the initial month following delivery [1]. Common symptoms for PPD include depressed mood, loss of interest in enjoyable activities, changes in sleep and appetite, excessive fatigue, feelings of shame and guilt, decreased concentration and suicidal acts or ideation [1]. The symptoms of PPD extend beyond the more mild symptoms associated with a condition called Baby Blues [1]. Baby Blues affects up to 70% of mothers, has a significantly shorter duration and is not associated with the same level of debilitation as PPD [4]. Many of the symptoms mentioned above are normal effects of having a new baby in the home: For example, sleep changes, appetite changes, tiredness and fatigue [1]. Due to this possible confusion and redundancy of symptoms, many women are unaware they may be suffereing from PPD. PPD is most commonly seen in the primary care setting, where obstetrician/ gynecologists and pediatricians are often the first to notice signs and symptoms and further evaluate the patient to generate a diagnosis [5].

PPD affects the mother, infant and entire family unit. PPD increases the risk of subsequent depression in the child. Furthermore, children of mothers who struggle with PPD can experience cognitive impairments as well as behavioral problems [5]. PPD alters how the mother perceives her new infant, this can lead to issues with bonding, breastfeeding, care and even increase the odds of neglect, abuse and maltreatment [6]. Even with a vast body of evidence discussing the significance of preventing, diagnosing and treating PPD, because of stigma and lack of awareness most women go undiagnosed and untreated [5]. Furthermore, there is a great deal of evidence that suggests depression, including PPD, can be a significant mental health risk factor that preempts suicidal actions and ideation. Mothers who do not access treatment for PPD are at an elevated risk for self-harm and suicide. Suicide is the second highest cause of death for women in the first year postpartum [7].

Researchers have been improving diagnostic tools and screening techniques for PPD. A 2017 study identified five key domains in regards to PPD risk factors, Ghaedrahmati et al. categorized the five domains as lifestyle, biological, social, psychiatric and obstetric [8]. Within the current body of research in regards to PPD, there are three specific exposure variables that stand out in regards to specifically increasing the risk of developing PPD: History of mental illness, domestic violence and abuse and drug use prior to and during pregnancy [8]. However, there is also evidence to hypothesize that interventions from healthcare workers can act protectively against the development of PPD. The World Health Organization notes that violence and low social support are significant determinants for PPD in mothers worldwide [9].

Many women experience symptoms and periods of depression at some point in their life. There are several research studies suggesting that a history of pre-pregnancy depression is one of the most influential and impactful exposures correlated to the development of PPD in mothers [10]. Women who suffer from untreated antenatal depression have a seven times higher risk of developing PPD compared to women with no history of antenatal depression symptoms or diagnoses. It can be argued that appropriately diagnosing and treating antenatal depression in women and specifically pregnant women, is a vitally important step in PPD prevention and prevalence reduction.

Illicit drug use, both pre-pregnancy and during pregnancy, can pose extreme risks to the health of the mother and the unborn infant. Drug use poses concerns and challenges to both physical health and mental health as well. In a study conducted by Dennis and Vigod, it was found that mothers were significantly more likely to experience PPD symptomatology, compared to mothers who did not express PPD symptoms, if they self-reported having a drug or alcohol problem or that their partner had a drug or alcohol problem [11]. In a study discussing the importance of home healthcare visitors for new mothers, Dauber et al. states that drug use and PPD are the two most treated comorbidities [12]. In regards to substance abuse, Dennis and Vigod, note a relationship between maternal substance abuse and PPD, which parallels other research on the topic [11]. Dauber et al. state that drug use increases the odds of PPD and makes treatment more extensive and difficult [12]. Another study by Prevatt, Desmarais and Jannsen, also found significant evidence to suggest that lifetime substance use is associated with a diagnosis of PPD [13]. Substance abuse is a specific psychosocial risk factor that is not commonly studied in regards to mental health. It is important to address the association between drug use and prenatal and postpartum depression in order to tailor treatment plans to appropriately adjust for positive mental health outcomes.

Domestic abuse and violence are more prevalently studied in relation to PPD. Intimate partner violence can include anything from degrading language, restricting personal autonomy, isolation from friends and family, sexual assault, physical aggression and bodily harm. Domestic violence rates are alarmingly high in the United States, Sharps, Laughon and Giangrande state that 4% to 8% of all pregnant women suffer some form of intimate partner violence and it is associated with severe physical and mental health complications [14]. Dennis and Vigod, highlight an important review performed by Ross and Dennis, which identified eight studies emphasizing a significant relationship between domestic violence and PPD [11,15]. Howard et al., notes that domestic violence can increase obstetric complications and is a significant risk factor in regards to mental health complications, such as PPD [16]. A Turkish study performed in 2016 found significantly higher rates of emotional and physical abuse in women with PPD [17]. Furthermore, Dennis and Vigod, note that there is strong relationship correlating substance abuse to intimate partner violence and general depression, which can then correlate to PPD [11].

Increasing numbers of health systems are offering the option of having a healthcare worker come into the expectant mother’s home to discuss caring for a new baby and caring for herself throughout the pregnancy and post-delivery. Additionally, home health visitors come again after the baby is delivered in order to address any concerns and help to answer questions. This facilitation supplies a support that may be hugely beneficial in preventing depression during pregnancy and PPD. Cutrona and Troutman, performed one of the first notable studies that showed a significant relationship between social support and PPD [18]. A 2017 study performed by Mundorf et al., demonstrates the efficacy of community health workers utilizing individually tailored education and outreach to combat PPD [19]. The study discusses how low-income women, immigrant women and women of color are less likely to have a previously established social network and how community health workers may be especially effective in regards to these vulnerable populations [19]. A 2011 randomized trial conducted by Taft et al. found that mentor-style social support is associated with a decrease in maternal drug use and PPD [20]. This information can map similarly onto combatting the previously mentioned risk factors associated with PPD. Social support can help to reduce depression prior to pregnancy, reduce substance abuse and reduce domestic violence and abuse. Health workers who are able to relate to the community members on an individualized level are tremendously effective in creating increased social support and possibly decreasing PPD [19].

While there is a great deal of literature discussing the abovementioned exposures associated with PPD, there is very little population-based research and even less data specifically focusing on Nevada. Up until 2018, Nevada utilized a study called Baby Birth Evaluation and Assessment of Risk Survey (BEARS), which was sponsored by the Nevada State Division of Public and Behavioral Health and contracted and conducted by University of Nevada, Reno, Nevada Center for Surveys, Evaluation and Statistics (CSES). There are several key questions in the survey that address depression, drug-use, intimate partner violence, postpartum depression and home healthcare worker visitation. The following paper will aim to utilize the Baby BEARS survey data from these questions in order to look at the relationships between these risk factors and PPD.

The primary objective for this cross-sectional study is to generate a quantitative data analysis that objectively looks at the relationships between risk factors and postpartum depression in Nevada mothers. This type of study and data has not been analyzed in Nevada. Population-based data helps researchers focus on the ecologic population. Furthermore, population-based research helps researchers to identify and hypothesize challenges and differences that affect the state. Four variables in particular appear to play a keystone role in regards to negative mental health outcomes, prior history of depression, drug-use, intimate partner violence and healthcare interventions. The subsequent paper hypothesizes that exposure to the first three variables will correlate to increased PPD diagnoses in Nevada mothers. The paper also hypothesizes that exposure to home health workers will effectively decrease PPD as well. Overall, the data will be highly reflective of Nevada mothers, some aspects of their mental health and well-being and possible risk factors and exposures that may influence their development of PPD. The subsequent paper is a fusion of mental health and maternal health. The subsequent paper aims to not only fill a gap in the literature but also to improve the community. Mental health is so often overlooked, but is inexplicably vital to public health. When PPD is prevented, mothers are happier, Nevada will become a more ethical and compassionate state and the community will be healthier.

Methods

Participants and procedures

Baby BEARS survey data from 2015-2016 was utilized for this project, with human subjects approval on May 18, 2016. Permission from the state to utilize the data was granted in January 2018. Baby BEARS used random sampling from Nevada birth certificates to select mothers that accurately represent rural, urban, racial and ethnic diversity. Baby BEARS also oversampled low birth weight births. The survey was sent out to mothers across the state of Nevada. The survey was directed at experiences related to the most recent pregnancy and baby. Some mothers opted to complete the paper survey and some completed the survey over the telephone. The response rate was 31.1% and the sample size is n=3,579 completed surveys. The Nevada Department of Public and Behavioral Health (DPBH) approved the printed survey materials [21]. Mailings were sent out for each new cohort sample on a schedule designed by DPBH. The first mailer was the pre-letter, which was mailed to all sampled mothers between 2 and 4 months after giving birth. The second mailer was the initial survey packet. This was sent to all sampled mothers one week after the preletter. The third mailer or tickler, was sent to all sampled mothers between 7-10 days after the initial survey packet. The fourth mailer was a second survey packet. This was mailed to all sampled mothers who had not responded and was sent out one to two weeks after the tickler. The fifth mailer was a third survey packet that was mailed to all nonresponding sampled mothers one to two weeks after the second survey packet. All attempts were made to ascertain a current and valid mailing address for all returned mail pieces.

The Nevada CSES assisted in completing a telephone follow-up for all mail non-respondents. Calling started between one to two weeks after the final survey packet was mailed out. Telephone surveys were completed utilizing the Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI) system. Every attempt was made to locate a current and valid telephone number for sampled mothers. Unanswered calls were required to be called back a minimum of 15 times over five different calling periods. If a respondent is not available then she will be called back a minimum of three times. All soft refusals received three refusal conversion attempts. There was a great deal of care taken to maximize the ability to contact the mothers by phone. The calls are staggered across varying week and weekend days and include daytime and evening hours. The mailer materials and phone interviews were offered in English and Spanish appropriate for the Nevada Hispanic population.

The entire data collection cycle, from the mailing of the pre-letter to the close of telephone interviews, lasted between 60 to 95 days. There was extensive supervision and monitoring to ensure the research assistants and interviewers were following the research methodology to protocol. Research assistants entered survey data and the data was checked for errors and validated prior to analysis.

Measures

Five specific survey questions were looked at within the Baby BEARS data. The outcome variable was a diagnosis of postpartum depression since the respondent’s new baby was born. This was identified through a single question asking the respondent “since your new baby was born, have you been diagnosed with postpartum depression by a medical provider”. The exposure variables looked at whether or not the respondent had 1) a diagnosis of depression in the 12 months prepregnancy, 2) experienced Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) within the 12 months pre-pregnancy and/or during pregnancy, 3) used cannabis within the one month pre-pregnancy and/or during pregnancy and 4) whether the respondent had a home health visitor come to their home during pregnancy. These were all single question, dichotomous “yes/ no” measures. Three covariates were identified, mother’s age, mother’s race/ethnicity and mother’s education level

Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed utilizing SAS 9.4. The Baby BEARS dataset is complex survey data. The data had to be stratified by the baby’s birth weight because low birth weight infants were oversampled in the initial sampling phase. Afterwards, poststratification weighting was performed in order to adjust for complex sampling. The first analysis performed on the data was a descriptive analysis utilizing the “proc surveyfreq” function in order to gain insight into the weighted frequencies of the exposures and covariates within postpartum depression and non-postpartum depression cases. The weighted chi-square test was used to assess factors associated with postpartum depression and is displayed with correlating p-values. To account for the complex study design, post-stratification weighted logistic regression was used for the multivariate models. Separate models were developed to assess the relationship between exposures and postpartum depression. Specific models were developed and adjusted odds ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) were calculated. A weighted multiple logistic regression was performed utilizing the “proc surveylogistic” function for the exposure variables in order to analyze the crude odds of postpartum depression for each exposure and then again while adjusting for the multiple covariates, age, race/ethnicity and education. Finally, a fully adjusted model was analyzed simultaneously adjusting for all covariates and variables (Tables 1-3).

| Characteristic | PPD | Non-PPD | Χ2 (d.f.)* | p-value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Un weighted | Un weighted % | Weighted | Weighted % | Un weighted | Un weighted % | Weighted | Weighted % | ||||

| n=286 | 8.84% | n=6250 | 9.05% | n=2948 | 91.16% | n=62798 | 90.95% | ||||

| Age | 0.83 (2) | 0.66 | |||||||||

| <20 | 15 | 8.43% | 290.29 | 0.42% | 154 | 91.57% | 3155 | 4.57% | - | - | |

| 20-30 | 166 | 9.55% | 3512 | 5.09% | 1533 | 90.45% | 33251 | 48.16% | - | - | |

| >30 | 105 | 8.49% | 2447 | 3.54% | 1261 | 91.51% | 26392 | 38.22% | |||

| Race/Ethnicity | 29.56 (4) | <0.01 | |||||||||

| White | 172 | 11.39% | 3259 | 4.72% | 1385 | 88.61% | 25353 | 46.72% | - | - | |

| Black | 36 | 14.63% | 1087 | 1.57% | 243 | 85.37% | 6345 | 9.19% | - | - | |

| Asian | 13 | 6.19% | 344.17 | 0.50% | 236 | 93.81% | 5214 | 7.55% | - | ||

| Hispanic | 58 | 5.12% | 1313 | 1.90% | 1034 | 94.88% | 24340 | 35.25% | - | - | |

| Other | 7 | 13.78% | 247.02 | 0.36% | 50 | 86.22% | 1545 | 2.24% | - | - | |

| Education Level | 3.27 (2) | 0.2 | |||||||||

| Less than H.S. | 43 | 8.39% | 982.29 | 1.44% | 479 | 91.61% | 10723 | 15.69% | - | - | |

| H.S./Some Post H.S. | 177 | 9.98% | 3794 | 5.55% | 1594 | 90.02% | 34230 | 50.09% | - | - | |

| College Graduate | 64 | 7.61% | 1416 | 2.07% | 852 | 92.39% | 17196 | 25.16% | - | - | |

| Pre-Pregnancy Depression | 306.72 (1) | <0.01 | |||||||||

| Yes | 106 | 44.23% | 2267 | 3.31% | 142 | 55.77% | 2859 | 4.17% | - | - | |

| No | 175 | 6.13% | 3880 | 5.67% | 2784 | 93.87% | 59469 | 86.85% | - | - | |

| Cannabis Use | 13.90 (1) | <0.01 | |||||||||

| Yes | 21 | 21.24% | 415.47 | 0.61% | 85 | 78.76% | 1541 | 2.27% | - | - | |

| No | 260 | 8.71% | 5748 | 8.47% | 2807 | 91.29% | 60217 | 88.66% | - | - | |

| Intimate Partner Violence | 18.61 (1) | <0.01 | |||||||||

| Yes | 15 | 29.60% | 306.13 | 0.44% | 38 | 70.40% | 728.02 | 1.06% | - | - | |

| No | 271 | 8.75% | 5944 | 8.62% | 2906 | 91.25% | 61973 | 89.88% | - | - | |

| Home Healthcare Visitor | 8.88 (1) | <0.01 | |||||||||

| Yes | 18 | 18.33% | 478.49 | 0.69% | 101 | 81.67% | 2132 | 3.09% | - | - | |

| No | 268 | 8.70% | 5772 | 8.37% | 2842 | 91.30% | 60587 | 87.85% | - | - | |

*Chi-square d.f.=degrees of freedom

‡ Chi-square test excludes missing data

Table 1: Characteristics of mothers diagnosed with Postpartum Depression (PPD) and weighted chi-square, post-stratification weighting, Baby BEARS, 2015-2016.

| Logistic Regression Analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Crude | Adjusted* | ||||

| Odds Ratio | 95% C.I.† | p-value‡ | Odds Ratio | 95% C.I.† | p-value‡ | |

| Pre-Pregnancy Depression | - | - | <0.01 | - | - | <0.01 |

| Yes | 12.15 | (8.70, 16.98) | - | 11.56 | (8.21, 16.27) | - |

| No (Reference) | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Intimate Partner Violence | - | - | <0.01 | - | - | <0.01 |

| Yes | 4.39 | (2.12, 9.12 ) | - | 3.81 | (1.88, 7.72) | - |

| No (Reference) | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Cannabis Use | - | - | <0.01 | - | - | <0.01 |

| Yes | 2.83 | (1.60, 4.99 ) | - | 2.32 | (1.25, 4.29) | - |

| No (Reference) | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Home Healthcare Visitor | - | - | <0.01 | - | - | <0.01 |

| Yes | 2.36 | (1.32, 4.21) | 2.54 | (1.42,4.55) | - | |

| No (Reference) | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

*Adjusted simultaneously for age, race/ethnicity and education

† C.I. Confidence interval

‡ T-test p-value

Table 2: Regression analysis of exposures for postpartum depression Baby BEARS, 2015-2016.

| Characteristic | Adjusted* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% C.I.† | p-value‡ | |

| Pre-Pregnancy Depression | <0.01 | ||

| Yes | 11.11 | (7.81, 15.81) | - |

| No (Reference) | 1 | - | - |

| Intimate Partner Violence | <0.01 | ||

| Yes | 3.06 | (1.35, 6.92) | - |

| No (Reference) | 1 | - | - |

| Cannabis Use | <0.71 | ||

| Yes | 1.17 | (0.51, 2.72) | - |

| No (Reference) | 1 | - | - |

| Home Healthcare Visitor | <0.01 | ||

| Yes | 2.54 | (1.40, 4.95) | |

| No (Reference) | 1 | - | - |

* Adjusted simultaneously for all other factors

† C.I. Confidence interval

‡ T-test p-value

Table 3: Fully adjusted model analysis of exposures for postpartum depression Baby BEARS, 2015-2016.

Results

Of the n=3,579 completed surveys, n=345 did not respond to the question regarding a PPD diagnosis since the new baby was born. The weighted frequencies and percentages for each of the outcome, exposures and covariates are presented in Table 1. The largest plurality of mothers were between the ages of 20 and 30, white and had at least a high school education. The unweighted number of mothers who reported a diagnosis of PPD was n=286. The unweighted percentage of mothers diagnosed with PPD was 8.84% and those without PPD was 91.16%. The unweighted and weighted frequencies for each of the exposures vary between PPD and non-PPD.

The weighted chi-square test for independence showed that race/ ethnicity, pre-pregnancy depression, IPV, cannabis use and home healthcare visitor had significant chi-squares and correlating p-values. Each chi-square value for the aforementioned covariate and exposure was greater than 3.84 with a corresponding p-value <0.05. The chisquares and correlating p-values for age and education were not significant (Table 1).

The crude and adjusted odds ratios for pre-pregnancy depression, IPV before or during pregnancy, cannabis use before or during pregnancy and home healthcare visitor are presented in Table 2. The adjusted odds ratios were adjusted for mother’s age, race/ethnicity and education level. The adjusted odds ratios for pre-pregnancy depression, IPV before or during pregnancy, cannabis use before or during pregnancy and home healthcare visitor were 11.56 (p-value ≤ 0.01, 95% CI=8.21, 16.27), 3.81 (p-value ≤ 0.01, 95% CI=1.88, 7.72), 2.32 (p-value ≤ 0.01, 95% CI=1.25, 4.29) and 2.54 (p-value ≤ 0.01, 95% CI= 1.42, 4.55) respectively Table 2.

The final table depicts the fully adjusted model. Table 3 presents the odds ratios for each exposure after adjusting simultaneously for all other factors, age, race/ethnicity, education and the other exposure variables. The fully adjusted odds ratios for pre-pregnancy depression, IPV, cannabis use and home healthcare visitor were 11.11 (p-value ≤ 0.01, 95% CI=7.81, 15.81), 3.06 (p-value ≤ 0.01, 95% CI=1.35, 6.92), 1.17 (p-value=0.71, 95% CI=0.51, 2.72) and 2.54 (p-value ≤ 0.01, 95% CI=1.40, 4.95) respectively Table 3.

Figure 1 compiles the crude, adjusted and fully adjusted models for each of the four exposure variables. The leading and lagging tail represents the 95% confidence interval and the odds ratio value is represented by the associated value to the right of the line.

Discussion

It is apparent that pre-pregnancy depression and IPV had the most significant increase in odds for PPD, while simultaneously controlling for age, race/ethnicity, education level and all other exposures concurrently. The literature suggested that these are two of the most influential exposure risk factors for PPD and it appears the Nevada data aligned with this hypothesis as well. In looking for the most important exposure risk factors to target for prevention interventions, it was apparent that pre-pregnancy depression and IPV were the two most critical.

The weighted chi-square test for independence indicated that race/ethnicity, pre-pregnancy depression, history of IPV, cannabis use and home healthcare visitor were significantly different between mothers diagnosed with PPD and mothers not diagnosed with PPD. The two groups differed significantly in regards to those covariates and exposure variables. The chi-squares and correlating p-values for age and education level were not significant and therefore indicated that there was not a significant difference in regards to age and education level between mothers diagnosed with PPD and mothers not diagnosed with PPD (Table 1).

All four exposures, 1) pre-pregnancy depression, 2) history of IPV before and/or during pregnancy, 3) cannabis use before and/or during pregnancy and 4) having a home healthcare visitor come to the home appeared to be significant risk factors in both the crude and adjusted models. After adjusting for the covariates, pre-pregnancy depression, IPV, cannabis use and having a home healthcare visitor appeared to increase the odds of PPD. While previous studies note that the first three exposure variables pose an increased risk of PPD development, this is not noted for a home healthcare visitor. As stated in the background portion, Mundorf et al., discussed the possible protective effect of social support supplied through community health workers, it was found that when pregnant women are able to have additional support from a community health worker, they are less likely to experience depression [19]. However, the present study found that having a home healthcare visitor come to the home actually significantly increased the odds of a PPD diagnosis. The crude and adjusted odds of PPD are increased when a home healthcare visitor comes to the home during pregnancy. Furthermore, the home healthcare visitor exposure variable remained significant in the fully adjusted model when all covariates and other exposures were controlled for simultaneously. This finding was suggestive of reverse causality. Very few of the sampled mothers reported having been visited by a home healthcare worker during their pregnancy, which resulted in a very low sample size and reduced power. After researching the criteria one must possess in order to qualify for a home healthcare visitor in the state of Nevada, it was apparent that the factors that qualified a mother to receive a home healthcare visitor were in fact also known risks for PPD as well. The Nevada Department of Public and Behavioral Health’s website notes that low-income mothers, first time mothers and mothers who have had complications with past pregnancies are eligible for a home health visit [21]. It appears that the qualifications to receive a home healthcare visitor are also possible risk factors that increase PPD and were not controlled for in the study design and therefore may have resulted in the appearance of reverse causality (Tables 2 and 3).

After adjusting simultaneously for all other factors, pre-pregnancy depression and IPV before and/or during pregnancy remained significant. Cannabis use before and/or during pregnancy was no longer significant after fully adjusting for all factors. This may have indicated that mothers who used cannabis before/during pregnancy may also have reported pre-pregnancy depression or IPV before/during pregnancy. There appeared to be some overlapping exposure risk variables that caused cannabis to no longer be significant in the fully adjusted model. With Nevada having recently legalized recreational cannabis, it was important to explore the affect of cannabis on maternal and mental health. While there are many other illicit substances associated with negative maternal health outcomes, the prevalence of cannabis and increased availability was what deemed it noteworthy for the present study in Table 3.

Based on the analyses presented in Tables 2 and 3, it was apparent the obvious significance on PPD of pre-pregnancy depression and IPV before and/or during pregnancy. Not only did these exposure factors remain significant in the crude analysis, but also after controlling for age, race/ethnicity, education level and the other exposure variables simultaneously.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of the present study were apparent within the study design. Baby BEARS is a large, population-scale survey that gathered information on Nevada mothers. Not only did Baby BEARS capture mothers of all ages, race/ethnicities and socioeconomic statuses, but it also spanned rural to urban. The data was complex and highly representative of the population in Nevada. However, this was a crosssectional study and therefore suffered from some limitations. A crosssectional study design, like this one, cannot accurately find causal relationships. This is because cross-sectional study designs suffer from issues associated with establishing temporality and selection bias associated with duration of disease. If temporality cannot be ensured, then generating a causal relationship is not possible. The present study only established possible relationships and correlations between the exposure variables and the outcome of PPD, absolutely no causation. Secondly, in regards to self-reporting and recall bias, it was apparent that from a cross-sectional snapshot one cannot establish if the respondents were recalling and reporting exposures with precision and accurate time recollection. Furthermore, there may be differential misclassification in mothers who reported a diagnosis of PPD. Mothers with a diagnosis of PPD may differentially over-report all risk factors and behaviors, compared to mothers who do not have a diagnosis of PPD. This differential misclassification would result in an upward skew of the odds ratios. The research design certainly affects interpretation considering the inability to establish temporality, possibility of differential recall bias and the possible presence of selection bias secondary to unknown duration of disease.

Another limitation was that the study may be totally missing a large proportion of mothers who are experiencing PPD symptomology but never received a PPD diagnosis. The survey question used to assess PPD specified that the mother had to have received a diagnosis from a medical provider. As discussed previously, many mothers who are suffering with PPD feel ashamed and consequently go undiagnosed. There was a possibility that significantly more surveyed mothers in Nevada actually have PPD but were never diagnosed. Since these mothers are unaware that they have PPD they did not respond to the survey question appropriately and the study missed them.

The final limitation was the lack of home healthcare visitors in Nevada. Home healthcare visitors are an important new trend in healthcare on the national level, however, from Table 1, one can see that this trend was still emerging in Nevada. Very few surveyed mothers noted a visit from a home healthcare worker during their most recent pregnancy. This certainly represented a limitation in regards to the analysis, however, the cause of the significant PPD risk associated with home healthcare visitors, as seen in Tables 2 and 3 was most likely a result of reverse causality as discussed above. If the only mothers who received home healthcare visitors are also mothers who were already at greater risk for developing PPD, there can appear to be an artificial correlative relationship that actually has nothing to do with the home healthcare worker. Future research could accommodate this by designing a cohort study to test the effect of a home healthcare visitor on PPD in all mothers, not only mothers who already possess significant risk factors for PPD.

Implications

A possible implication of this study is to vastly improve and expand maternal mental healthcare in Nevada. Prenatal care is a huge focus of public health in Nevada. Maternal/child health mainly targets the physical aspects of health and unfortunately is not as focused on mental health. It is made apparent by the present study that there are several key mental health exposure risk factors that appear to be related to the development of postpartum depression. With this knowledge, women’s healthcare providers can expand screening procedures and provide improved services and support to mothers who may be more likely to develop postpartum depression. With improved screening, interventions can be tailored and administered more effectively, resulting in improved health outcomes. Not only will this be invaluable to mothers’ mental health, but will also positively impact newborns. A healthy mother is one of the most important building blocks for a child. Furthermore, when postpartum depression is more publically discussed, identified and treated, healthcare providers will be assisting in suicide prevention as well. New mothers are at great risk of dying by suicide and when mental healthcare is highlighted and treated, suicide will decrease in postpartum mothers [7].

Further studies can go on to study mental healthcare exposures more closely and look at possible comorbid exposures that affect PPD. Hopefully this study opened a dialogue about maternal mental healthcare and paved the way for future researchers to better understand and treat PPD in Nevada mothers. The ultimate goal of this research is to help build healthy mothers, healthy children and healthy families.

Conclusion

The results suggest that there is a statistically significant relationship between pre-pregnancy depression and history of IPV in mothers who are diagnosed with PPD. Furthermore, it appears that more research needs to be conducted on the effect of a home healthcare visitor on PPD. Previous literature suggests that a home healthcare visitor is beneficial for mothers, however this study fails to indicate that due to limited provision of home healthcare workers in Nevada. Mental and maternal healthcare must further address and adjust postpartum care for mothers who report these exposures. PPD is not only a negative health outcome for mothers but also for their infants and must continue to be a prevention priority in public health.

References

- Pearlstein T, Howard M, Salisbury A, Zlotnick C (2009) Postpartum depression. Am J Obstet Gynecol 200: 357-364.

- Stewart DE, Vigod S (2016) Postpartum depression. N England J Med 375: 2177-2186.

- Wisner K, Sit D, McShea M, Rizzo D, Zoretich RA, et al. (2013) Onset timing, thoughts of self-harm, and diagnoses in postpartum women with screen-positive depression findings. JAMA Psychiatry 70: 490-498.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2017a) Reproductive health: Depression among women.

- Georgiopoulos AM, Bryan TL, Wollan P, Yawn BP (2001) Routine screening for postpartum depression. J Fam Pract 50: 117-122.

- Sampson M, Duron JF, Mauldin RL, Kao D, Davidson M (2017) Postpartum depression, risk factors and Child’s home environment among mothers in a home visiting program. J Child Fam Stud 26: 2772-2781.

- Lindahl V, Pearson JL, Colpe L (2005) Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and the postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health 8: 77-87.

- Ghaedrahmati M, Kazemi A, Kheirabadi G, Ebrahimi A, Bahrami M (2017) Postpartum depression risk factors: A narrative review. J Educ Health Promot 6: 60.

- Silverman ME, Reichenberg A, Savitz DA, Cnattingius S, Lichtenstein P, et al. (2017) The risk factors for postpartum depression: A populationâ€based study. Depress Anxiety 34: 178-187.

- Dennis C, Vigod S (2013) The relationship between postpartum depression, domestic violence, childhood violence and substance use: Epidemiologic Study of a large community sample. Violence Against Women 19: 503-517.

- Dauber S, Ferayorni F, Henderson C, Hogue A, Nugent J, et al. (2017) Substance use and depression in home visiting clients: Home visitor perspectives on addressing clients’ needs.J Community Psychol 45: 396-412.

- Prevatt BS, Desmarais SL, Janssen PA (2017) Lifetime substance use as a predictor of postpartum mental health. Arch Womens Ment Health 20: 189-199.

- Sharps PW, Laughon K, Giangrande SK (2007) Intimate partner violence and the childbearing year: Maternal and infant health consequences. Trauma Violence Abuse 8: 105-116.

- Ross LE, Dennis CL (2009) The prevalence of postpartum depression among women with substance use, an abuse history, or chronic illness: A systematic review. J Womens Health 18: 475-486.

- Howard L, Oram S, Galley H, Trevillion K, Feder G (2013) Domestic violence and perinatal mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos Med 10: e1001452.

- Bulut S, Alatas E, Gunay G, Bulut S (2017) The relationship between postpartum depression and intimate partner violence. J Clin Anal Med 8: 164-167.

- Cutrona CE, Troutman BR (1986) Social support, infant temperament and parenting self-efficacy: A mediational model of postpartum depression. Child Dev 57: 1507-1518.

- Mundorf C, Shankar A, Moran T, Heller S, Hassan A, et al. (2017) Reducing the risk of postpartum depression in a low-income community through a community health worker intervention. Matern Child Health J 22: 520-528.

- Taft A, Small R, Hegarty K, Watson L, Gold L, et al. (2011) Mothers' advocates in the community (MOSAIC)-non-professional mentor support to reduce intimate partner violence and depression in mothers: A cluster randomised trial in primary care. BMC Public Health 11: 178.

- Division of Public and Behavioural Health (DPBH) (2018) Nevada home visiting (MIECHV).

Citation: Alexander-Leeder C, Yang W, Mburia I (2019) Effects of Mental Health Exposure Factors on the Prevalence of Postpartum Depression: A Nevada Population-Based Study. J Preg Child Health 6:401. DOI: 10.4172/2376-127X.1000401

Copyright: © 2019 Alexander-Leeder C, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 3712

- [From(publication date): 0-2019 - Feb 22, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 3063

- PDF downloads: 649