Effects Of Dietary Diversity and Eating Behaviors On Adolescent Girlâs Nutritional Status In Government Schools, Akaki Kality Sub City, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A School-Based Cross-Sectional Study

Received: 30-Mar-2022 / Manuscript No. snt-22-55683 / Editor assigned: 01-Apr-2022 / PreQC No. snt-22-55683(PQ) / Reviewed: 14-Apr-2022 / QC No. snt-22-55683 / Revised: 19-Apr-2022 / Manuscript No. snt-22-55683(R) / Published Date: 26-Apr-2022 DOI: 10.4172/snt.1000165

Abstract

Background: However, there is little information about adolescent eating behaviors, dietary diversification and nutritional status of adolescent girls, especially urban and school based. The purpose of this study was to assess the effects of dietary diversity and eating behaviors on school girl’s nutritional status in government schools in Akaki Kality Sub City, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Methods: A total of 384 adolescent girls between the ages of 10 to 19 years were participated. A school-based cross-sectional study design was employed. Qualitative and quantitative methods were used in the study area. Data was coded, imported and analyzed and computed by STATA V14. The Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05.

Result: Mean age of schoolgirls was 15.67±1.60 years. Overall stunting and thinness of schoolgirls were 15.0% (60) and 14.1% (54) respectively and about 5.2% (20) schoolgirls were overweight and almost half of schoolgirls had low dietary diversity score with their mean (±SD) dietary diversity score of 3.61 ± 1.33. The risk factors for stunting were schoolgirls who used to drink sugary fluids [OR: 18,95% CI (2.49-130.89)], schoolgirls who often feel hungry in the week [OR: 5.2,95% CI (1.95-14.05)], schoolgirls whose family lower income status [OR: 4.97,95% CI (2.46- 10.06)], and schoolgirls whose lower BMI/age [OR: 1.53,95% CI (1.27-1.84)]. Similarly, the risk factors for thinness were schoolgirls who used to drink sugary foods [OR: 13.84, 95% CI (1.74-109.97)].The schoolgirls who used to practice daily eat on late [OR: 9.77, 95% CI (4.60-20.72)] and irregular and who never perform enough healthy exercise [OR: 1.95, 95% CI (1.07-3.55)]. The school feeding program to mitigate poor nutrition outcome following erratic feeding and meal skipping behaviours.

Keywords

Adolescent Girls; Stunting; Dietary Diversity; Meal Skip; Erratic Feeding

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines adolescents as young people aged 10–19 years. Adolescence is the only time following infancy when the rate of physical growth increases. For this to happen there is a greater need for calories and nutrients. Thus, it is a time of increased nutritional requirements. Poor nutrition can have lasting effects on an adolescent’s cognitive development, resulting in decreased learning ability, poor concentration, and impaired school performance [1]. Stunting in adolescents is the collective effect of poor nutrition, mainly during the first two years of life whereas body mass index is associated to an individual’s food consumption pattern. Under nutrition in adults more truly reflects the nutritional status of a community [2].

Different lifestyle factors and unhealthy eating habits developed during adolescence can lead to serious diseases later in life. Healthy eating behavior during adolescence is an essential precondition for physical growth, psychosocial development, and cognitive performance [3]. Lifestyle changes including food habits are often more obvious among urban adolescents as they are typically the ‘early adopters’ unsettled among other things to their attraction for innovation and high exposure to commercial marketing in cities [4]. Adolescents are mostly open to new ideas and they show interest and many habits acquired during adolescence will last a lifetime [5].

In Ethiopia, children and adolescent comprises 48% of the population and about 25 percent is girls but studies among this age group were not enough. Studies revealed that under nutrition was common problem among adolescent girls, of which, a study in the rural community of Tigray indicated that 25.5% and 58.3% of adolescent girls were stunted and thin, respectively [2], 37.8% were thinness, 2.0% overweight and 0.4% had obesity [6]. Similarly, in Jimma, 53.2% were underweight, Hawassa, 12.9% were overweighed and 2.7% had obesity. Malnutrition affects a large portion of the adolescent and youth population in Ethiopia. According to Ethiopian demographic and household survey 2016 report, the proportion of non-pregnant adolescent girls aged 15 to 19 years with acute malnutrition, thinness (BMI <18.5) was 36 percent. Adolescents (age 15-19) are more likely to be thin (36%) than older women and 2.4 percent of the girls’ group were reported to be overweight or obese (CSA, 2012). Looking closely dietary diversity and eating behaviors of adolescent, especially girls, provides a unique opportunity to break the intergenerational cycles of malnutrition. Therefore, this study aimed to assess adolescent girls eating behaviors’ and dietary diversification and its association with their nutritional status in Akaki Kality sub city, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia [7]

Method

Description of the study area

Akaki-Kality is one of the ten sub-cities of Addis Ababa and was divided into 11 woredas located in the South-Eastern part of Addis Ababa, is 20 km far from the city’s center and covers a total area of about covers a total area of 156 km2. The sub city shares boundary with Bole Sub city in the North, Kirkos and Nifas-Silk-Lafto Sub cities in the North West and Finfinnee-Zuria, a special zone of Oromia regional state in the South. Since its establishment, the old town (Akaki) has been the hub of industries of Addis Ababa and the nation in general. According to the Central Statistics Authority (CSA) projections of July 2019, the population of the Akaki Kality Sub city is estimated to reach 205,385 out of which 100,513 are male and 104,872 are female [8]. The Sub city has a population density of 1,653.7 per square kilometer. There are 78 primary and 15 secondary schools out of these 23 primary and 9 secondary schools are belonging to the government [9]. A total number of 100,533 students were enrolled during the study conducted from 0 to 12 grades and of these 63, 336 of the students were learning in the government schools and 23,434 were adolescents of these 12, 620 were girls adolescents. The study was conducted in selected 12 government schools. A total of 384 adolescent girls were selected proportionally from all schools across the woreda. The main criterion for sub-sampling was female students with the age group 10 - 19 years [10].

Study period and design

The study used a school-based cross-sectional study design that employed both qualitative and quantitative data collection methods to assess eating behaviors and dietary diversity status of adolescent girls and its association on nutrition status in the study area. Akaki Kality sub city was chosen with purposive sampling methods. The study was conducted from January to February 2020 [11].

Sample size determination

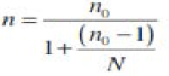

Cochran formula was used to determine the sample size (Cochran, 1963).

Where: n0 is the desired sample size, z is the selected critical value of desired confidence level or is the statistic corresponding to the level of confidence, the standard normal deviate at 95% confidence level (1.96); p is the estimated proportion of an attribute that is present in the population taken prevalence 51% from similar studies on undernutrition among adolescents’ girls in schools in Addis Ababa (Yoseph et al. 2014), q is 1-p, e is the desired level of precision(0.05). Cochran pointed out that if the population is finite, then the sample size can be reduced slightly. Finite population correction formula was done to calculate the final sample size and to produce a sample size that was proportional to the population. The total number (N) of adolescent girls’ population was 12, 620.

Where: n = 373 was calculated and considering 3% non-response rate 11 respondents were added, so the sample size = 384.

The two-stage sampling technique was used to select a sample of an adolescent girl. At the first stage, six primary and six secondary schools were randomly selected from 23 primary and 9 secondary governmentowned schools based on the proportional allocation of adolescents. In the second stage [12], one adolescent girl was randomly selected from each school. The first respondent was selected randomly through balloting from among the first school lists of students and thereafter systematic sampling was used. To find the sampling interval in the respective school, total lists of adolescent girls in the respective school registers obtained and proportionate weighting was divided by the required sample size in that school which was allocated proportionally from the total 12 schools in the sub city against the final sample. This was done daily during the weekdays/school days for three weeks until the target sample size meet [13].

Source and study population

All adolescent girls who were attended in the selected government primary and secondary in the study areas. The study population was a total of 384 adolescent girls between the ages of 10 to 19 years who registered and attended in the selected 12 government primary and secondary schools in the year 2019/20 in Akaki Kality sub city and who were finally sampled through probabilistic two-stage sampling technique and selected proportionally [14].

Exclusion and Inclusion criteria

All adolescent girls aged 10 to 19 years who registered and attended in the selected government primary and secondary schools and enrolled in the academic year 2019/2020 and who showed a willingness to participate in the study by signing an informed consent form were part of the study [15]. The exclusion criteria were adolescent girls with obvious physical deformities for anthropometric measurements and/ or who were seriously ill to be interviewed and who were not willing to participate. Moreover, Students who were aged less than 10 years old or above 19 years old were excluded [16].

Sampling techniques and procedures

The study applied a probability sampling method in quantitative research technique that was based on randomization and allowed the determination of what population segment went into the sample. Among schools in the sub city owned with government, all the primary and secondary schools where adolescent girls were enrolled included in the sampling frame. Then, 12 schools were selected randomly. Therefore, the sample size assigned to the respective school proportionally to the size of the school students and therefore; a twostage simple random sampling procedure was used in the selection of representative samples to avoid bias and a proportional sampling frame prepared from identified government school based on the school size recruited from each class by taking school rosters as a sampling frame [17].

Sampling techniques and procedures- qualitative

A total of ten focus group discussion (FGD) were conducted in the targeted schools and all participants were selected purposively (nonprobability sampling method). Informed consent was obtained prior to each FGD. On each of schools from 14 to 19 years adolescent girls who were registered and enrolled in selected schools were participated in focus group discussion. Participants were then approached face-to-face by the data collectors [18].

Study variables`

The nutritional status of schoolgirls was explained with height for age and BMI for age status. Dependent variables of the study were nutritional status, eating behaviors and dietary diversification of schoolgirls [19]. Independent variables used in the study were socioeconomic and demographic factors, social environment factors, dietary intake, food habits, food pattern, influences, knowledge on health and weight status, lifestyle, and physical activity [20].

Data collection procedures and technique

Both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods were employed to obtain detailed and reliable data for the analysis. Quantitative data collection; Data were collected using two types of measurements: Administration of the standard questionnaire through face-to-face interview and anthropometric measurements [22]. Section one: structured questionnaires were used to get information about Socio-economic demographic for schoolgirls and their family characteristics, social environment factors, dietary intake, food habits, food pattern, influences, knowledge on health and weight status, lifestyle, physical activity, dietary diversity and adolescent eating behaviors were used to collect the quantitative data and anthropometry measurement also conducted [22].

Section two: An individual dietary diversity questionnaire recommended by FANTA (Swindale and Bilinsky, 2006) was adopted and modified to collect data on dietary diversity. The questionnaire was divided into 24-hour recall dietary diversity which was used to minimize recall bias and it fits to the recall period [23<]. Moreover, a seven-day food frequency was also noted to their household dietary diversity and regular access to food. Therefore, a seven-day food frequency was used to determine frequency of accessing to different food stuffs. The 24-hour diet recall data were used to calculate individual dietary diversity. Foods were categorized into nine groups as recommended by the FANTA. Simple counting of food groups was done to arrive at individual food scores, which ranged from 1 to 9 (with 1 being the lowest score), as recommended by the FAO [24]. The score was categorized in to three levels as consumption of foods [0-3] categorized as low dietary diversity groups, [4-6] categorized as medium dietary diversity and [7-9] categorized as high dietary diversity in 24 hours before the interview.

Anthropometric Measurements

The nutritional status was assessed based on the anthropometric measurements used to assess the physical development of adolescent girls. Mid Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC) of students was a measured using standard tape meter. Height was measured once with a portable Height Scale to the nearest 0.1 cm. The body weight was measured using the platform (digital scale) weighing Scale to the nearest 0.1 kg that has the capacity to measure 0-140 kg [25].

Data quality control

The English version of the structured questionnaire was translated into the local language “Amharic” and again back translated to English by another translator to check for consistency and accuracy. To ensure the validity of the initial and back translation of the questionnaire, a discussion was conducted with the data collector team to review, edit, and double-check the questionnaire. Also, two volunteers, female teenagers were involved in parallel in discussing the layout, the wording, and the understanding of questions. Data collectors and supervisors were trained for three days on the standardization of the anthropometric tools and on the purpose of the study, data collection tools, and procedure, how to interview, maintaining confidentiality and privacy [26]. The questionnaire was administered in 38 respondents (10%) of the total sample before the actual survey out of the study setting to ensure clarity, ordering, consistency, and acceptance of the questionnaire. This allowed modifications to the questionnaires by correcting mistakes and inclusion of foods that have been missed out or elimination of foods that are not applicable in the community [27]. Ambiguous questions were corrected to ensure clarity and to elicit the required information therefore enhancing reliability. All anthropometric tools were tested to ensure that each tool produces the same measure of a standard object. The scales were checked by placing items of known weight on them after every 10 measurements and regularly checked and adjusted to zero after each measurement. To improve the quality of the data, data collectors were closely supervised, and each completed questionnaire was checked to ascertain that all questions were properly filled and corrected [28].

Data processing and analysis

The data was cleaned, coded, entered to SPSS (Version 20), and then imported to Stata (Version 14) statistical packages for further analysis. The study had used both descriptive statistics and econometric technique for analyzing the quantitative data. Bivariate analysis was undertaken to assess the association between all independent variables and the outcome variable [29]. Means and standard deviations were calculated for continuous variables while frequency and percentage used to describe dietary practices of the adolescents for meal frequency, meal skipping and snacking habits, food patterns, knowledge and behaviors, and media-related variables and participants’ concerns of media influences on food choice. Cross-tabulation, chi-square, and pair wise significant correlation tests were applied for individual variables both for dietary diversity, eating behaviors, height for age, and BMI for age status of adolescent girls, within the independent variables to see the multicollinearities and with dependent variables to see the strong correlation [30, 31]. Chi-square and Pearson correlation was employed to identify the association between independent and outcome (dependent) variables and used to estimate the influence of independent variables to the nutritional status. Chi-square analyses were performed to detect significant relationships between BMI z-scores and height for age z-scores among all participants according to factors affecting adolescents’ behaviors and dietary diversity on nutritional status [32]. The level of stunting (height for age z-scores), which was an indicator of chronic malnutrition, and thinness (BMI for age z-scores), which was another indicator of malnutrition, were calculated using WHO Athro-Plus software [33]. The econometric technique used in the study was logistic regression model to determine the likelihood/ probability of being malnourished and have poor eating behaviors. The probabilistic analysis ordered logistic regression and a multinomial logistic regression model was used to assess dietary diversity and eating behaviors association on schoolgirl’s nutritional status. Based on the factors established in the Chi-square test, logistic regression was employed to find out some possible risk factors of nutritional status among schoolgirls. The level of statistical significance using the logistic regression and Chi-squared test was set at P-value < 0.05. All variables having a p-value of <0.05 in the analysis were candidates for the order logistic regression model. In the analysis, variables with p-value <0.05 were taken as significant predictors for stunting and thinness at a 95% confidence interval. In the analysis, new variables were generated in the STATA through combing two variables these are adolescents think that they eat healthy food (think health food) and adolescent health status (AdselfHealth) called adolescent eating behaviors [34]. Category one was assigned as an adolescent who has good eating behaviors whereas category 4 was poor. Multinomial logistic regression was used to check for robustness and predictor for adolescent eating behaviors.

Ordered logistic regression was used to assess the effect of dietary diversity and eating behaviors on adolescent girl’s nutritional status. Both significant variables with height for age and BMI for age status from bivariate correlation analysis and strong significant predictor variables from dietary diversity and eating behaviors regression model were used in the final nutrition status of the adolescent girls’ model. A test of multicollinearities had been conducted to determine the correlation of the independent variables [35]. As stated in Mendenhall and Sincich (2003), multicollinearity refers to the extent to which an independent variable could be explained by other independent variables in the analysis. If it is too high, this can have harmful effect on regression. Multicollinearity was examined using variance inflation factor (VIF) and correlation coefficients [36]. The values of Mean VIF for explanatory variables were checked. The data were tested for heteroscedasticity using the Breusch-Pagan test [37].

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval was obtained from the research and ethics review committee of Addis Ababa University. A support letter was also obtained from the University and got permission from concerned sub city offices. The classes were conducted before data collection and each student’s consent was obtained the day before the data collection through informed consent. The researcher ensured that all information obtained will be kept in strict confidence and will be used only for the study. Confidentiality of all the information was maintained [38].

Results and Discussion

Socioeconomic and Demographic Characteristics of School Girls

The primary and secondary cycle school schoolgirls were proportionally represented and total of 384 participants were surveyed with a 100% response rate. The mean age of the study population was 15.67±1.60 and all of them were unmarried. Similarly; found the mean age (years) of experience from rural adolescent schoolgirls of West Bengal as 13.33 ± 1.09. Result Table 1 below indicated that 91(24%) were aged 10-14 (early adolescence) and 293(76%) were in the age category of 15–19 (late adolescence) [39]. This was inconsistent with where 87.3% belonged to early adolescence (10-14 years) and 12.7% to late adolescence (15-19 years) age group. This was due to exclusion of different class students in later studies, while all school students from 10-19 years were included in a school-based setting in the study. The average family size of the study groups was 5.31±2.05 and the largest family size was 14. A large majority of the schoolgirls, 246(64.1%), and 330(85.9%) under the study were living with their father and mother, and both parents were alive, respectively. Among the study participants [40], 112(58.33%) intermediate cycle schoolgirls and 134(69.79%) secondary cycle schoolgirls do live with their mother and father. This finding supported with other scholars, , found that the majority (84.7%) of the respondents lived with their parents.

Variables |

Categories | No (%) | Mean ±SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Schoolgirls Age Groups (n=384) | Early schoolgirls (10 - 14) | 91 (24) | |

| Late schoolgirls (15 - 19) | 293 (76) | ||

| Age (Years) (n=384) | 15.67 ± 1.596 | ||

| Education Level (n=384) | Intermediate (5-8 grade) | 192 (50) | |

| Secondary schools (9-12 grade) | 192 (50) | ||

| Households family size of Schoolgirls | (4, 14) | 5.31± 2.053 | |

| Schoolgirls live with | Both parents | 246(64.1) | |

| Father only | 18 (4.7) | ||

| Mother only | 33 (8.6) | ||

| Other specify | 87 (22.7) | ||

| Schoolgirls parents living status | Both alive | 330 (85.9) | |

| Both died | 5(1.3 ) | ||

| Father alive | 17 (4.4) | ||

| Mother alive | 32 (8.3) | ||

| Household Income Monthly (ETB) | </= 1,210 | 68 (17.7) | |

| 1,210 to 8,970 | 136 (35.4) | ||

| I do not know | 180 (46.9) | ||

| Schoolgirls family car | No | 351 (91.4) | |

| Yes | 33 (8.6) | ||

| Family television | No | 16 (4.2) | |

| Yes | 368 (95.8) | ||

| Parents occupation | Farmer | 5 (1.3) | |

| Govt employee other than Teacher | 163 (42.4) | ||

| Merchant | 85 (22.1) | ||

| Other specify | 99 (25.8) | ||

| Teacher | 32 (8.3) | ||

| Schoolgirls parent education level | Basic education | 115 (29.9) | |

| High school | 144 (37.5) | ||

| Higher education | 76 (19.8) | ||

| Illiterate | 42 (10.9 ) | ||

| Vocation | 7 (1.8) |

Table 1: Socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of schoolgirls in Akaki Kality subcity, Addis Ababa, 2020. (n=384)

Source: The researcher original findings, 2020

One hundred thirty-six (35.4%) schoolgirls replied that their family monthly income is ranged between 1,210 to 8,970 ETB. About 351(91.4%) schoolgirls reported that they do not have a family car whereas 368(95.8%) said they do have a television in the family. A total of 181(94.27%) intermediate cycle schoolgirls and 170(88.54%) secondary cycle schoolgirls do not have a family car whereas 180(93.75%) intermediate cycle schoolgirls and 188(97.92%) secondary cycle schoolgirls do have family television.

A total of 163(42.4%) schoolgirls family occupation type was government employee other than a teacher, and 115(29.9%) and 144(37.5%) schoolgirls responded that their family education status was basic education and high school, respectively. Parents for 61(31.77%) intermediate cycle schoolgirls could read and write whereas 117(60.94%) secondary cycle schoolgirls were high school.

School girl’s knowledge on healthy eating behaviors, eating practices, and perceived health and weight status (selfassessed)

In the study, nine out of ten schoolgirls had not known medical problems of their weight used to consume healthy foods, and seven perceived positive about their health status and average active as compared to other schoolgirls of the same age-based on self-assessment [41]. About half of schoolgirls used to eat their regular meals after under-five children. About three out of four schoolgirls had fair and above knowledge on healthy eating behaviors and balance diet and used to be served a meal in their family is normal.

And also about one out of five schoolgirls had poor knowledge of water, sanitation, and hygiene practices, and one-tenth of intermediate and 42(21.88%) in secondary schoolgirls had poor knowledge on healthy eating practices of balanced diet Table 2 and 3. This study showed that not all schoolgirls knew healthy eating behaviors, schools have the potential to reach out to schoolgirls at this critical age when eating habits are flooring a way for healthy behavior and dietary habits to adulthood and this finding is strongly supported both with the theoretical literature on health promotion model and empirical evidence that knowledge is the foundation to change the attitude and practices of the behaviors and schoolgirls spend more time of the day at school, thus providing a practical environment for education about healthy food choices is necessary (Foster et al. 2008) and poor dietary practices were because of low nutrition knowledge level led to poor health-seeking behavior [42].

| No (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Self-assessed health status | No | 100 (26.0) |

| Yes | 284 (74.0) | |

| Schoolgirls known medical Ds | No | 342 (89.1) |

| Yes | 42 (10.9) | |

| Self-assessed knowledge on healthy eating practices | Poor | 66 (17.2) |

| Not bad | 156 (40.6) | |

| Good | 129 (33.6) | |

| I do not know | 33 (8.6) | |

| Self-assessed perception on eating healthy food | No | 74 (19.3) |

| Yes | 310 (80.7) | |

| Self-assessed knowledge on good water, sanitation, and hygiene practices | Poor | 89 (23.2) |

| Good | 119 (31.0) | |

| Not Bad | 110 (28.6) | |

| I do not know | 66 (17.2) | |

| Self-assessed how to feel health and nutrition club influencing their weight | No influence | 367 (95.6) |

| Average influence | 15 (3.9) | |

| A strong and important influence | 2 (0.5) | |

Table 2: Schoolgirls self-assessed knowledge on healthy eating practices, their health, water, sanitation, and hygiene practices, in Akaki Kality sub city, Addis Ababa, 2020. (n=384)

Source: The researcher original findings, 2020

Around half 198 (52%) schoolgirls regularly skip their meal of this one out of five skipped their breakfast whereas the rest skipped mixed and two out of five reported regularly felt hungry and an equal number of schoolgirls both from primary and secondary schools felt hungry on the regular base. The findings are supported in other similar studies like revealed that in a school-based cross-sectional study on the eating habits of adolescent girls in Nigerian urban secondary school found out that meal skipping was the main eating habits displayed. On the contrary, 134 (35%) schoolgirls used to consume snacks between meals. Biscuits (n: 36), injera (n: 33), and fruit (n: 28) were among the types of snacks schoolgirls ate [43].

About more than half of schoolgirls parents did not care about their body weight status and its change and of these, seven to nine out of ten schoolgirls did not have a special diet for their body weight, never tried losing or gaining weight plan. Surprisingly, in study 176 (91.67%) intermediate and 146(76.04%), secondary school students did not read or follow media concerning diet/nutrition issues. This study showed that a large majority of adolescent girls did not have special attention on their health, low interest in healthy readings, low parent attention, and low experience and knowledge on healthy stature and its health implication which might be linked with low school health and nutrition topics through different courses such as via physical education [44].

A large majority, 366 (95%) schoolgirl’s drunk water frequently of these almost half used 2-4 cups of water. About, unhealthy foods, more than half of schoolgirls used to consume carbonated beverages (fizzy drinks), full-sugar beverages, and were adding sugar to their drinks (hot or cold). These findings supported with other scholar showed consumption of sugary soft drinks was reported by 22.7 percent of adolescents 13-17 years [45], the inconsistencies in data might be explained with the current study includes from 10 to 19 years and carbonated and full-sugar beverages. The findings also supported in other similar studies, revealed that in a school-based cross-sectional study on the eating habits of adolescent girls in Nigerian urban secondary school found out that consumption of fast foods along with soft drinks were the main eating habits displayed.

Two hundred fifty-five (66%) schoolgirls never had school daily pocket money however these schoolgirls reported that they had experience eating outside the home at least once per week. This might be explained by the low socio-economic status of the parents and the assumption of many of the schools is nearby to the communities. About one out five, 59(15%), and 19(5%) schoolgirls commonly used to buy pasty potato crisps, and potato crisps from the school canteen, respectively. This study also supported other scholars said that consumption of fruits and vegetables often declines when entering adolescence, while the consumption of unhealthy food types increases. This has been confirmed in studies examining the consumption of soft drinks and fast food [46].

Two hundred seventeen (57%) schoolgirls had meals in a group with their families on a regular base and 294 (76%) schoolgirls had experience eating their meal in front of watching television and these findings might be showing one of the issues on schoolgirls eating behaviors needs to be corrected in particular with parents’ involvement.

Three hundred thirty-five (87.2%) and 314 (81.8%) schoolgirls reported that their family size and school meal sharing do affect their meal size, respectively. Other empirical findings supported this study that large family size and low slot of the meal will affect schoolgirls’ daily requirements. The obvious physiological growth in adolescence affects the body’s nutritional needs increasing adolescents’ requirements for energy and all nutrients to support rapid growth rate and development [47].

Schoolgirls food frequency and dietary diversity status

Looking food frequency of schoolgirls, the frequency of food consumption in the total sample in a week, 334(86%) and 331(86%) never had ate meat and dairy throughout the week in the contrast, about 139(36%) and 235(61%) had eat carbohydrate (mainly bread) and fat sources food (mainly food oils) throughout the week. Others 134(35%) and 117(30%) schoolgirls reported consumption of vegetables and fruit sources on average 3-4 times and 1-2 times per week, respectively. Almost nine out of ten schoolgirls used to eat Injera with wot regularly per week and an equal number of schoolgirls observed among intermediate and secondary schools. A study in Adama showed that among the participants, all (100%) of them consumed grains or other starchy roots and tubers (staples), followed by dark green vegetables (80.0%), other fruits, and vegetables (79.3%), and legumes (66.7%). The difference might be explained due to the difference in socioeconomic background between the towns. The majority of 186 (48%) of schoolgirls had low dietary diversity score, less than four, and their mean (±SD) dietary diversity score was 3.61 ± 1.33. (see table 4), whereas studies among schoolgirls in Adama city, central Ethiopia to assess nutritional status, and its associated factors showed based on the 24 h dietary recalls the mean Dietary Diversity Score (DDS) was 4.2 ± 2.01 [48]. The inconstancies might be the sample size and the latter study sample size explanations two times and other explanations might be the socio-economic difference between the two towns. In the study, dietary diversifications differences observed among schoolgirls, who ate snacks between meals, drink fizzy regularly, read or follow media concerning diet issues, food supplements and involved in food preparation at home. Looking at the socio-economic status of the community and low pocket money allocation with schoolgirls, the probability of practicing these foods at home is very less and finding showed that schoolgirls food habits were more influenced on outside of the house practices, seemingly during schooling and media-driven and which is supported with other scholars like Benavides vaello 2005, socio-environmental factors, family, peers, and media, are believed to influence an individual’s food habits and food choices. A total of 129 (69.35%) and 152 (79.58%) schoolgirls had low and medium dietary diversifications scores, respectively of these, nine out of ten schoolgirls felt their health status is good and had not known medical disease reported and majority, 133 (71.51%) and 121(63.35%) schoolgirls who had low and medium dietary diversifications scores, respectively used to eat outside their house once per week which is supported with other scholars like Benavidesvaello, (2005), socio-environmental factors, family, peers, and media, are believed to influence an individual’s food habits and food choices [49].

| No (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Do you think, you are being served food in good way in your family/house | No | 66 (17.2) |

| Yes | 285 (74.2) | |

| I do not Know | 33 (8.6) | |

| Schoolgirls think their family take care of weight status | No | 228 (59.4) |

| Yes | 156 (40.6 ) | |

| Schoolgirls following any special diet now | No | 357 (93.0 ) |

| Yes | 27 (7.0) | |

| Schoolgirls ever tried losing weight | No | 295 (76.8) |

| Yes | 89 (23.2) | |

| Schoolgirls ever tried gaining weight | No | 332 (86.5) |

| Yes | 52 (13.5) | |

| When Schoolgirls change weight, parent | Encourage me | 138 (35.9) |

| Discourage me | 15 (3.9) | |

| They do not care | 231 (60.2) | |

Table 3: Schoolgirls weight status and weight management, in Akaki Kality subcity, Addis Ababa, 2020. (n=384)

Source: The researcher original findings, 2020

| No (%) | Mean ±SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary diversity status/24HRs | Low dietary diversity [0-3] | 186 (48) | 3.61 ± 1.326 |

| Medium dietary diversity [4-6] | 191 (50) | ||

| High dietary diversity [7-9] | 7 (2) | ||

Table 4: Schoolgirl dietary diversity status, in Akaki Kality subcity, Addis Ababa, 2020. (n=384).

Source: The researcher original findings, 2020

In the table 5, nearly two out of ten schoolgirls who used to eat three to four times vegetable and how had almost on every day on carbohydrate foods over the week frequently before the survey day had medium level of dietary diversity scores whereas schoolgirls who had episode of less than one time on fruits, and never eat meat and milk related foods in the last 7 days from the survey day had low dietary diversity score status.

| Adolescent DDS Status # (%) | P value (CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Low | Medium | High | ||

| Schoolgirls, eat vegetables in last 7 days | None | 29 (7.6) | 15 (3.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.00(0.000 - 0.008) |

| 1-2 times | 49 (12.8) | 33 (8.6) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| 3-4 times | 56 (14.6) | 75 (19.5) | 3 (0.8) | ||

| 5-6 times | 43 (11.2) | 60 (15.6) | 4 (1.0) | ||

| 7 times | 9 (2.3) | 8 (2.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Schoolgirls, eat fruit in last 7 days | None | 63 (16.4) | 40 (10.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0.000 (0.000 - 0.008) |

| 1-2 times | 62 (16.1) | 52 (13.5) | 3 (0.8) | ||

| 3-4 times | 38 (9.9) | 66 (17.2) | 2 (0.5) | ||

| 5-6 times | 20 (5.2) | 28 (7.3) | 2 (0.5) | ||

| 7 times | 3 (0.8) | 5 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Schoolgirls, eat meat in last 7 days | None | 170 (44.3) | 161 (41.9) | 3 (0.8) | 0.000 (0.000 - 0.008) |

| 1-2 times | 13 (3.4) | 15 (3.9) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| 3-4 times | 3 (0.8) | 11 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| 5-6 times | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.0) | 3 (0.8) | ||

| 7 times | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Schoolgirls, eat diary in last 7 days | None | 168 (43.8) | 161 (41.9) | 2 (0.5) | 0.000 (0.000 - 0.008) |

| 1-2 times | 12 (3.1) | 17 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| 3-4 times | 4 (1.0) | 9 (2.3) | 4 (1.0) | ||

| 5-6 times | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| 7 times | 1(0.3) | 2 (0.5) | 0(0.0) | ||

| Schoolgirls, eat carbohydrate in last 7 days | None | 22 (5.7) | 9 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.000 (0.000 - 0.008) |

| 1-2 times | 24 (6.2) | 12 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| 3-4 times | 28 (7.3) | 39 (10.2) | 1 (0.3) | ||

| 5-6 times | 42 (10.9) | 64 (16.7) | 4 (1.0) | ||

| 7 times | 70 (18.2) | 67 (17.4) | 2 (0.5) | ||

Table 5: Characteristics, frequency of foods and dietary diversity status of schoolgirls in Akaki Kality subcity, Addis Ababa, 2020.

Source: The researcher original findings, 2020

More than half, 117 (62.90%), and 70 (37.63%) schoolgirls who had low dietary diversifications scores used to eat fat (linked with food oil) and carbohydrate (all bread-related foods) almost every day on a regular base respectively, 56 (30.11%) also ate vegetables three times on average per week whereas nine out of ten of these schoolgirls never ate meat and dairy products in the weekly base. Dietary diversity has been used as proxy indicators for food quality and security (Allen, 2003), which may be due to its ability to capture consumption of both macro and micronutrients or a more balanced diet in the general sense without the need of measuring the quantity of food consumed, which may, in turn, be difficult in certain contexts.

Schoolgirls who had low dietary diversifications scores reported that their family does not take care of their weight status (116, 62.37%), they never follow any special diet (174, 93.55%), they never read or follow media concerning diet issues (158, 84.95%) and never take any food supplements (168, 90.32%). Schoolgirls who had low dietary diversifications scores said, any activities performance once per week (64.52%), same activity during the holiday and non-holiday time 85(45.70%), and felt health and nutrition club in their school not influencing their weight 181(97.31%).

Schoolgirls physical activity, lifestyle & media influences

A large majority, 312(81.2%) and 235(61.2%) schoolgirls reported that they had water and latrine facilities in their homes. Level of education different observed among schoolgirls in terms of knowledge on water hygiene and sanitation practices. This might explain with as schoolgirls increase their education to the next level there might be potential knowledge change on understanding water hygiene and sanitation practices. Schoolgirls’ social environment factors have been shown in table 6.

Variables |

No (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Availability of water in the house | No | 72 (18.8) |

| Yes | 312 (81.2) | |

| Availability of toilet in the house | No | 149 (38.8) |

| Yes | 235 (61.2) | |

| Schoolgirls felt family size affects meal size | No | 49 (12.8) |

| Yes | 335 (87.2) | |

| Schoolgirls felt school food sharing affects meal size | No | 70 (18.2) |

| Yes | 314 (81.8) | |

| Health and nutrition club presence in school | No | 284 (74.0) |

| Yes | 42 (10.9) | |

| I have no idea | 58 (15.1) | |

| Schoolgirls buy food from the school canteen or school environment | No | 206 (54) |

| Yes | 178 (46) | |

| Schoolgirls read book, magazine, or comics daily | No | 112 (29.2) |

| Yes | 272 (70.8) | |

| Number of hours per day spend on reading by schoolgirls | < an hour a day | 153 (39.8) |

| 1 to 2 hours a day | 207 (53.9) | |

| > 2 hours a day | 24 (6.3) | |

| Number of hours per day schoolgirls spend watching television or video | None | 29 (7.6) |

| Less than an hour a day | 38 (9.9) | |

| 1 to 2 hours a day | 170 (44.3) | |

| More than 2 hours a day | 147 (38.2) | |

| Schoolgirls perception, reading influences on their food choice | No | 288 (75.0) |

| Yes | 31 (8.1) | |

| I do not know | 65 (16.9) | |

| Schoolgirls perception, on television advertisement and program influence on their eating behaviors | No | 39 (10.2) |

| Yes | 345 (89.8) | |

| Schoolgirls read or follow any media, concerning diet/food protocols | No | 322 (84) |

| Yes | 62 (16) | |

Table 6: Characteristics of schoolgirls social and environment factors, in Akaki Kality subcity, Addis Ababa, 2020. (n=384)

Source: The researcher original findings, 2020

About 284 (74.0%) and 206(54%) surveyed schoolgirls explained that no health and nutrition club in their school and do not buy food in their school canteen or school environment, respectively. A total of 272 (70.8%) schoolgirls used to read any book daily, of these 207(53.9%) schoolgirls spend one to two hours per day on reading however, 322 (84%) schoolgirls do not read or follow any media concerning diet issues. About 355(92.4%) schoolgirls reported reading do not influence on their food choice. However, 200 (52.1%) food topics and 125 (32.5%) music related to magazine topics/advertisements influence girl’s food choices. Other empirical evidence supported this study, which was conducted by UNICEF in the Somali region, 85 percent of schoolgirls had not heard about balanced diets and no school information on health and nutrition which could be explained by the absence of nutrition education.

In study groups, eight out of ten schoolgirls spent watching television/video on average more than an hour per day, and similarly, nine out of ten schoolgirls interested in the television advertisement program focused on food and drink related, and entertainments. Television advertisement program does influence for 345(89.8%) schoolgirls eat behaviors, among these 226(58.9%) schoolgirls said eat behaviors is strongly influenced by television advertisement. About half of intermediate schoolgirls had an interest in advertisement focused on food and drink-related whereas secondary schoolgirls had an interest in watching entertainments [KANA television, Films, Music] television programs.

A total of 186(96.88%) intermediate schoolgirls and 159(82.81%) secondary schoolgirls said that television advertisement programs influenced their eating behaviors. Similarly, intermediate schoolgirls perceived that their weight and health was influenced by television advertisement 72(37.50%) whereas secondary schoolgirls perceived that weight and health were influenced by the school environment 50(26.04%). These findings strongly supported by other scholars’ studies such as advertising, probably television and magazines, influenced preferences in 80% of these Nepalese adolescents (Sharma, 1998). Dietary changes are even more prominent among urban adolescents, as they are more exposed to brand marketing and advertising campaigns that target urban areas (Williams, 2013).

More than half, 200(52.1%) of schoolgirls normally go to bed early and 270(70.3%) schoolgirls normally get up early every day. About 326(84.9%) schoolgirls walk on foot when traveling to and from school. Two hundred fifty-three (65.9%) schoolgirls sitting down and 128(33.3%) standing or walking around while doing school breaks. Around one-third 123(32.0%), the schoolgirls are spending 1 to 2 hours a day playing games whereas 142(37.0%) never played. A large majority of schoolgirls 379(99%), do not smoke. A total of 192(100.00 %) intermediate and 187(97.40%) secondary schoolgirls never smoke a cigarette in a lifetime and 176(91.67%) intermediate and 152(79.17%) secondary schoolgirls never take any food supplements. A total of 157(81.77%) intermediate and 182(94.79%) secondary schoolgirls have started menstruation. Schoolgirls’ physical activity, lifestyle & media influences have been shown in Figure 3.

About 203(52.8%) schoolgirls reported that they do not perform enough exercise to keep healthy. Schoolgirls tended to think that they were not performing 226(58.9%) any kind of physical activity on daily basis. Around half of schoolgirls do have about the same physical activity performance during holidays. Most schoolgirls, 344(89.6%) involved in food preparation at home daily. This evidence might be supported by other empirical findings on the frequency of exercise often declines as adolescents grow older. The walking distances get shorter, and car driving increases [47, 48]. National surveys in Norway indicated that the activity level of the average Norwegian adolescent was below the current recommendations of at least 30 minutes of physical activity a day.

Schoolgirls nutritional status

Table 7 showed that the average weight and height of school schoolgirls in the study place were 44.06kg (± 6.730) and 153.50cm (±5.825), respectively. Similarly, mean BMI and MUAC were 18.74 kg/ m2 (±2.965) and 23.52cm (±2.232), respectively.

Classifications |

Nutrition Status | (No, %) | (Mean ±SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight of schoolgirls (kg) | (23, 74) | 44.06 (± 6.730) | |

| Height of schoolgirls (cm) | (136, 170) | 153.50 (±5.825) | |

| BMI of schoolgirls (kg/m2) | (10, 30) | 18.74 (±2.965) | |

| MUAC of schoolgirls (cm) | (17, 28) | 23.52 (±2.232) |

Table 7: Anthropometric characteristics of schoolgirls compared to Anthroplus 2007 WHO references in Akaki Kality subcity, Addis Ababa, 2020. (n=384)

Source: The researcher original findings, 2020

In the study weight difference was observed among schoolgirls with water in their home, tried to lose their weight, who started menstruation and schoolgirls normally get up early in the morning. In the same line, it was found that height difference observed among schoolgirls with water and latrine in their home, tried to lose their weight, who started menstruation, family television, regular fizzy drinks, perform kind of physical activities daily and regularly eat on dark green leafy vegetable category.

In the study also BMI difference was observed among schoolgirls with those had latrines in their home, who started menstruation and who perform regular physical activities this might be explained with the availability of latrine in the home encourage utilization, improve sanitation and health, in turn, improve keeping health and doing extra exercises which finally contributed to the BMI status.

A large majority of 324(84.4%) of schoolgirls had normal nutritional status according to height for age z-scores, and it was also found that 308(80.2%) of schoolgirls had normal nutritional status according to BMI for Age z-scores. The prevalence of overall stunting and thinness of schoolgirls was 60(15.0%) and 54(14.1%), respectively and 20 (5.2%) schoolgirls were overweight. This study had almost similar stunting prevalence of the adolescents at 15.6% (have short stature for their age) whereas the lower prevalence of thinness and higher prevalence of overweight as compared with study in Adama. The comparison showed that there might be similar chronic food insecurity across the towns whereas the difference in the socioeconomic and acute context across the towns. Similarly, found the prevalence of stunting as 34.8%. This difference could be due to the differences in the age groups considered for the study and/or the criteria used for classification of stunting as a later study was done among 10-14 years girls using Vishveshwara Rao’s classification for height-for-age. Fifty-four (14.1%) had thinness, this was consistent with the study done by Das et al found the prevalence of thinness was 14.7% and 20(5.2%) schoolgirls had overweight. Comparison of Height-for-age (z-score) and BMI-for-age (z-score) in the study population was against WHO reference 2007 (5 to 19 years).. Schoolgirls 271(83.64%) who have been diagnosed as normal and 41(73.21%) had moderate stunting reported that their meal size was affected by school sharing [49, 50]. Regular felt hungry due to household food insecurity among 30(53.57%) moderate stunting, and 3(75.00%) severe stunting schoolgirls. Near to half of the schoolgirls with better of the family had normal nutritional status both for height and BMI for age.

More than 4 out of five schoolgirls who had normal status against height for age reported that they think they used to eat healthy food, used to eat starchy foods regularly, and preferred to have physical education in their school and similarly, more than half of schoolgirls who had normal status against height for age reported used to eat dark green leafy vegetable foods regularly.

One-third normal for height-age and more than half normal for BMI-age of schoolgirls used to eat carbohydrate and fat (linked with the vegetable oil) regularly. On the contrary, more than 4 out of five schoolgirls who had thinness never ate dairy on a regular base.

Half of the schoolgirls who had moderate stunting and all with severe stunting reported do not have adequate water facilities in their home and poor water hygiene and sanitation knowledge. This might be explained with the known UNICEF conceptual frame and underline causes of the malnutrition linked with three different causal blocks of this poor water hygiene and sanitation is among the causes [51].

According to chi-squared test, factors associated with schoolgirl’s malnutrition with stunting were lack of water and latrine, knowledge on water hygiene sanitation practices, parent’s occupation, poor parent education, school sharing affect meal size, perceived healthy food and ate starchy staples food per day. The findings were strongly supported by other scholar studies, factors most frequently mentioned in association with stunting were lack of hand washing, latrines, and poor sources of drinking water and also living in rural areas, poor education of parents, food insecurity, big family size, and poverty were associated with both stunting and thinness. Measure of association with chi square test on schoolgirl’s height for age status has been shown in table 8.

More than three out of four schoolgirls had both normal height and BMI for age status. This might show that the probability of one form of nutrition indices might indirectly be showing the other indices outcome as proxy measurement. Surprisingly, more than two-thirds of schoolgirls who had both thinness and overweight used to drink fizzy soft drinks and add sugar in any drink except water and this finding might need further empirical studies and explanation [52].

Schoolgirls who had moderate thinness 31(91.18), severe thinness 19(95.00%), overweight 18(90.00%), and obesity 2(100.00%) reported that used to eat a family meal in their home together with other adult family members. These findings might show that schoolgirls feeding in their house monotonous foods with their family whatever they have with no proper balancing diets in line with the daily requirements which might implication on the weight status of schoolgirls.

In this study, factors associated with malnutrition in schoolgirls with thinness were skipping breakfast while going to school due to household food insecurity; eat carbohydrates on regular basis throughout the week, and parent concern when schoolgirls change weight. This study is more supported by other similar studies factors associated with schoolgirls with thinness were dietary factors such as meal frequency, meal skipping, and poor dietary diversity. Measure of association with chi square test on schoolgirls BMI for age status has been shown in table 8 (Annex). No Table 8.

Source: The researcher original findings, 2020

Source: The researcher original findings, 2020

Source: The researcher original findings, 2020

Logistic regression modeling

Factors affecting schoolgirls poor eating behaviours

The final model for schoolgirls eating behaviors with multinomial logistic regression showed that the model was statistically significant as compared to the null model with no predictors and the pseudo R2 indicated that 34% of the variation of the model explained by the independent variable with powerful predictor.Schoolgirls who have known medical disease are 45.7 times more likely to have poor eating behavior and schoolgirls who reported felt hungry are 4.7 times more likely to have poor eating behaviours [53]. Similarly, schoolgirls whose parents never encourage or did not care about their weight change are 3 times more likely to have poor eating behavior and schoolgirls who perceived advertisement has an influence on their food choice are 2.7 times more likely to have poor eating behaviours. All of these was statistically significant at Prob > chi2 (0. 0000).

Determinants of schoolgirls stunting status

The final model for factors determined schoolgirls stunting with ordered logistic regression showed that the model was statistically significant as compared to the null model with no predictors and the pseudo R2 indicated that 60% of the variation of the model explained by the independent variable with powerful predictor.

Schoolgirls who used to drink sugary fluids are 18.06 times [95% CI (2.49- 130.89)] and schoolgirls whose family income status is lower are 4.97 times [95% CI (2.46- 10.06)] more likely to be stunted. Similarly, schoolgirls who often feel hungry in the week are 5.24 times [95% CI (1.95- 14.05)] more likely to be stunted in their latter life. Moreover, the study showed that schoolgirls whose lower BMI/age are 1.53 times [95% CI (1.27- 1.84)] more likely to be stunted in their latter life. All of these was statistically significant at Prob > chi2 (0. 0000). These findings are contradicted with other scholar study which mentioned that factors most frequently in association with stunting were lack of hand washing, latrines, and poor sources of drinking water [54].

Determinants of schoolgirls thinness status

The final model for factors determined schoolgirls thinness with ordered logistic regression showed that the model was statistically significant as compared to the null model with no predictors and the pseudo R2 indicated that 56% of the variation of the model explained by the independent variable with powerful predictor. Schoolgirls who used to drink sugary fluids are 13.84 times [95% CI (1.74-109.97)] and schoolgirls whose family lower income status is 2.29 times [95% CI (1.33-3.92)] more likely to be thin. Similarly, schoolgirls who used to practice daily eat on late and irregular are 9.77 times [95% CI (4.60- 20.72)] and who never perform enough healthy exercise are 1.95 times [95% CI (1.07- 3.55)] more likely to be thin. All of these was statistically significant at Prob > chi2 (0. 0000). These findings supported with other scholar empirical evidence that factors associated with malnutrition in schoolgirls with thinness were dietary factors such as meal frequency, meal skipping, and poor dietary diversity [45, 51].

Qualitative section

A total of 80 schoolgirls were approached in 10 focus group discussion sessions. Age of the discussants was from 13 to 19 years of age.

Schoolgirls perception on eating behavior and dietary diversity

Most of the discussants (58) in the focus group discussion expressed their feeling on eating behavior as practicing of daily eating with different foods as repeated habits. This also the definition of eating behavior. However, still there were some students did not define eating behavior this might implies that they do not have a knowledge which could be contributing to likelihood of practicing against the recommend good eating behavior. The same groups of discussants also quoted that dietary diversity means eating variety of foods. They believed that eating different type of foods will create a healthy looks and shaped body. These findings indicated that majority of the participants had some knowledge on dietary diversity concept [55].

(focus group discussion 01-03, 06, 09, 10, January 2020, Akaky- Kaliti, Addis Ababa)

The study discovered out some outlier information from the qualitative finding on the eating behavior of students on commercial food around school.

I and my friends are eating different foods from the market around the school which is full of sugar and oil such as pasty, potato crisps, sandwiches and others.” (Five discussants from focus group discussion 01 and 06, January 2020, Akaky-Kaliti, Addis Ababa

This may be due to the fact that the market is easily available around the school and wants to attract the students by making low price, sugary and easily availability and students are using these foods without understanding of effects on their health and nutrition status.

Schoolgirls attracted with, in their daily life

Recently, in Ethiopia there are different television channels and advertisement which showing lifestyle and food programs on which young peoples can easily attracted with and this can be the potential influencing factors that students easily access and adapt on their day to day life. This was confirmed with about half of the participants on focus group discussion. Said that,

We mostly looked at different outside and Ethiopia television channels such as Arab and KANA TV and interested, to see their foods and dressing styles and wish to eat the foods and practicing different lifestyle on which we felt it’s a sign of modernization….”. (40 schoolgirls from focus group discussion 02, 04, 07 and 10, January 2020, Akaky-Kaliti, Addis Ababa)

Schoolgirls observing effects on eating behavior and dietary diversity

Most of the discussants [56] in the focus group discussion stated that there were few students in their class who regularly felt hungry over the week and mostly skip their breakfast meal which was mainly associated with lack of food in their home, and they thanked for the government which started food at school.

(Focus group discussion 02, 03, 06 and 07-10, January 2020, Akaky- Kaliti, Addis Ababa)

The study revealed that most participants have irregular eating behavior and less diversified foods. This were discussed in the focus group discussion by saying

We commonly practiced eating on late hours and eat when we feel hungry not respecting the schedule. Injera with Shiro and bread were the most common food most of our family used to eat over the week and our family could not prepare different foods since they could not afford to buy different foods types…..’’ (Ten discussants from focus group discussion 04 to 08, January 2020, Akaky-Kaliti, Addis Ababa)

Beside less dietary diversification and erratic eating by the participants, most of the families do not control to different behaviors which students practicing [57]. For example, on the focus group discussion one of them was said that

I stayed long time on watching television channels after school time, mostly eat late, my family does not care about my weight status and rather my family are worried to feed me whatever they have in the house without hungry me and my family considered that checking my body and healthy status on regular base did not sense as normal practice by the community, may be due to their low education status, and they also felt it as modernization come from out of Ethiopia.’’ (a 17-year-old discussant from focus group discussion 07, January 2020, Akaky-Kaliti, Addis Ababa)

In addition to the above there were evidence observed in the discussion in some participants described about the medical problem which might be linked with nutrition deficiency [58].

I have low blood disease and I take iron folic acid food supplements on regular base….’’ (five discussants from focus group discussion 01 and 09, January 2020, Akaky-Kaliti, Addis Ababa)

Some of the discussants [24] in the focus group discussion explained as observed different body structures which is not the same as compared with other same age groups like themselves in the class such as very thin, fat and very short body size students and they did not have knowledge on why it happened. These students also did not have interest about obtaining further information on health and nutrition since never heard any information in the school and they believed as themselves as healthy since they never did get any illness and they can take any food without difficulties [59-61].

(Focus group discussion 02, 05, 10, January 2020, Akaky-Kaliti, Addis Ababa)

Schoolgirls suggestion to contribute for the solution

There were irregularly eating behavior and felt hungry over the week and mostly skip their breakfast meal which was mainly associated with lack of food at home.

Most of the discussants [62] in the focus group discussion explained that students should keep their health through eating good food timely at home and reduce commercial foods in particular sugary foods/ drinks since it will reduce appetite and low food intake. They also need the food provided by the government in the school to be maintained as it is their alternative food sources while they are in the school especially for those students skip their meal [63].

(Focus group discussion 01-03, 06 and 07-10, January 2020, Akaky- Kaliti, Addis Ababa)

There were long time on watching television channels after school time, mostly eat late, family does not control students behaviours and health w

Conclusion

The overall stunting and thinness of schoolgirls in the study area were 60 (15.0%) and 54 (14.1%), respectively and about twenty (5.2%) schoolgirls were overweight. This study revealed that about half of schoolgirls had low dietary diversity score with their average score of 3.61 which was supported with the qualitative finding that the schoolgirls eating behaviors in the study area were erratic, mostly felt hungry over the week and skip their breakfast meal while they go to school which was mainly associated with lack of food at home. Besides, schoolgirls had experience of watching television channels long time on after school time, mostly eat late; family does not control students’ behaviors and health. Government started feeding in the school is the main alternative food sources while they are in the school especially for those students skip their meal. The econometric modeling empirical evidence rejected the null hypothesis that there was nutritional outcome difference among the eating behaviors and dietary diversification status of schoolgirls. Schoolgirls who used to drink sugary foods and whose family lower income status had both stunting and thinness effects. Whereas schoolgirls who often feel hungry in the week and lower BMI/ age had effects on schoolgirls stunting status. And schoolgirls who used to practice daily eat on late and irregular and who never perform enough healthy exercise had association with schoolgirl’s thinness status.

References

- Abahussain NA (2011) Was there a change in the body mass index of Saudi adolescent girls in Al-Khobar between 1997 and 2007? J Family Community Med 18: 49-66.

- Abdella A, Belachew T, Jarso H (2016) Nutritional Status and associated factors among primary school adolescents of pastoral and agro-pastoral communities, Mieso Woreda, Somali Region, Ethiopia: A comparative cross-sectional study. J Public Health Epidemiol 8: 297-310.

- Mulugeta A, Hagos F, Stoecker B, Kruseman G, Linderhof V (2009) Nutritional status of adolescent girls from rural communities of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev 23:5-11.

- Yasin A, Benti T (2015) Nutritional Status and Associated Risk Factors Among Adolescents Girls in Agarfa High School, Bale Zone, Oromia Region, South East Ethiopia. J Nutri Food Sci 4: 445-452.

- Roba AC, Gabriel-Micheal K, Zello GA, Jaffe J, Whiting S (2015) A low pulse food intake may contribute to the poor nutritional status and low dietary intakes of adolescent girls in rural southern Ethiopia. Ecol Food Nutr 54: 240-254.

- Allen LH (2003) Interventions for micronutrient deficiency control in developing countries: Past, present, and future. J Nutr 133: 3875-3878.

- Tariku A, Abdela K, Kassahun A, Mesele M, Abebe Z (2016) Household food insecurity predisposes to undiversified diet in northwest Ethiopia: finding from the baseline survey of nutrition project. BMC : 52-67.

- Anthroplus W, Computers P (2009) WHO AnthroPlus for Personal Computers Manual Software for assessing growth of the world’s children. Geneva: WHO.

- Benavides-Vaello S (2005) Cultural influence on the dietary practices of Mexican Americans: A review of the literature. Hispanic Health Care International 3: 27-35.

- Amel B, Guillaume B, Cécile B, Olivier B, Ivan LM, et al. (2009) Search for viable responses to the nutrition challenges of vulnerable populations, summary of the exploratory study, Danone Communities

- Elling B, Glomnes ES, Te Velde SJ, Knut-Inge K (2008) Determinants of adolescents soft drink consumption. Public Health Nutrition 11: 49-56.

- Central Statistical Agency (CSA) (2017) Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey.

- Central Statistical Agency (CSA) (2014) Shape files of Ethiopia and Regions. Addis Ababa: Central Statistics Authority. Cochran W (1977) Sampling Techniques

- Central Statistical Agency (CSA) (2012) Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey

- Central Statistical Agency (CSA) (2007) Summary of Statistical Draft Report of National Population Statistic. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Central Statistics Authority

- Cochran WG (1963) Sampling Techniques Sampling Techniques, 2nd Ed., New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc: New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Miaoulis, George, and R.D

- Charles D, Delisle HF, Receveur O (2011) Poor nutritional status of schoolchildren in urban and peri-urban areas of Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso). Nutr J; 2011; 10:34.

- Das DK, Biswas R (2005) Nutritional Status of Adolescent Girls in a rural area of North 24 Parganas district, West Bengal. Indian J Public Health 49:18-21.

- David (2008) Promotion of nutrition education Dekeba interventions in rural and urban primary schools in Machakos District, Kenya. J Applied Biosciences 6: 130-139.

- Dennison CM, Shepherd R (1995) Adolescent food choice: an application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. J Human Nutri Diete 8: 9-23.

- Aurino E, Fernandes M, Penny M (2016) The nutrition transition and adolescents’ diets in low- and middle-income countries: a cross-cohort comparison. Public Health Nutr, 20: 72-81.

- Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011 (2012) Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Agency and ICF International.

- WHO /FAO (2007) Guidelines for measuring household and individual dietary diversity. Version 3, Rome, Italy

- FMoH/UNICEF (2016) In-School Adolescent Girls’ Nutrition Knowledge, Attitude and Practice (KAP) Survey in Somali, Gambella, SNNP and Oromia Regions, Ethiopia

- Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance (FANTA) (2006) Developing and Validating Simple Indicators of Dietary Quality and Energy Intake of Infants and Young Children in Developing Countries: Summary of findings from analysis of 10 data sets Working

- Group on Infant and Young Child Feeding Indicators. Academy for Educational Development (AED), Washington, D.C

- Simone F, Lin B, Guthrie HJ (2003) National trends in soft drink consumption among children and adolescents age 6 to 17 years: Prevalence, amounts, and sources, 1977/1978 to 1994/1998. J Am Diet Assoc 103:1326-1331.

- Simone F, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Fulkerson JA, Hannan P(2001) Fast food restaurant use among adolescents: associations with nutrient intake, food choices and behavioral and psychosocial variables. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 25:1823-1833.

- Gebremariam H, Seid O, Assefa H (2015) Assessment of nutritional status and associated factors among school going adolescents of Mekelle City, Northern Ethiopia. Inter J Nutr Food Sci 4: 118-124.

- Delisle H, Chandra-Mouli V, de Benoist B (2001) Should adolescents be specifically targeted for nutrition in developing countries. To address which problems, and how?

- Assefa H, Belachew T, Negash L (2013) Socioeconomic factors associated with underweight and stunting among adolescents of Jimma Zone, South West Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study

- Gina K, Regina M, Seghieri C, Nantel G, Brouwer I (2007) Dietary diversity score is a useful indicator of micronutrient intake in non-breast-feeding Filipino children. J Nutri 137: 472-477.

- Larson N, Story M (2009) A reviews of environmental influences on food choices. Ann Behav Med 38 Suppl 1: 56-73.

- Maiti S, De D, Chatterjee K, Jana K, Ghosh D (2011) Prevalence of stunting and thinness among early adolescent schoolgirls of paschim medinipur district, west Bengal. Int J Biol Med Res 2:781-799.

- Onis M, Onyango AW, Borghi E, Siyam A, Nishida C (2007) Development of a WHO growth reference for school-aged children and adolescents. Bull World Health Organ 85:660-667.

- Onis M (2006) WHO child growth standards: Length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height, and body mass index-for-age. WHO.

- Yetubie M, Haidar J, Kassa H, Fleming L, Fallon J (2010) Socioeconomic and Demographic Factors Affecting Body Mass Index of Adolescents Students Aged 10-19 in Ambo (a Rural Town) in Ethiopia. Int J B 6: 326-332.

- Kahssay M, Mohamed L, Gebre A (2020) Nutritional status of school going adolescent girls in Awash Town, Afar Region, Ethiopia. J Envir Public Health.

- Mohamed (2019) A research thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Science (food, nutrition, and dietetics). School of public health and applied human sciences. Kenyatta university

- Muthoni CN, Imungi J, Ngatia E (2012) Snacking in association with dietary intake and nutritional status of adolescents in two national high schools in Nairobi Kenya. Food Sci Quality Manage 30: 11-24.

- Pentz MA (2009) Understanding and preventing risks for adolescent obesity. Adolescent Health: Understanding and Preventing Risk Behaviors: 147-164.

- Carmen PR, Aranceta J (2001) School based nutrition education: Lesson learned and new perspective. Public Health Nutri 4: 131-139.

- Nalini R, Evans M, Byrd-Williams C, Evans A, Hoelscher D (2010) Dietary and Activity Correlates of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Consumption Among Adolescents. Pediatrics 126: 754-761.

- Ransom E, Elder LK (2003) Nutrition of Women and Adolescent Girls: Why It Matters. Medi: 54-61.

- Roba, Ransom AC, Elder (2003) Nutrition of women and adolescent girls: Why it matters

- K Roba, Abdo M, Wakayo T (2016) Nutritional Status and Its Associated Factors among School Adolescent Girls in Adama City, Central Ethiopia. J Nutr Food Sci 6: 493.

- Gayle S, MacFarlane A, Ball K, Worsley A, Crawford D (2007) Snacking behaviours of adolescents and their association with skipping meals. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 4: 36-60.

- Sharma (1998) Trends in the intake of ready- to-eat foods among urban school children in Nepal. SCN News, 16: 21-29.

- Shelomenseff, Andreoni (2000) California nutrition and physical activity guidelines for adolescents

- Shepherd, Raats (2006) "The Psychology of food. Frontiers in Nutritional Science ". City

- Shetty PS, James WPT (1994) Body Mass Index: a measure of chronic energy deficiency in adults. FAO Food Nutri 56.

- Shrimpton R, Victora CG, Onis M, Lima RC, Blössner M, et al. (2001) Worldwide timing of growth faltering: implications for nutritional interventions. Pediatrics 107: E75.

- Stang J, Story MT (2005) Guidelines for Adolescent Nutrition Services. Edu training mater child Nutri: 45-51.

- Stang (2001) "Adolescent Nutrition In: Nutrition through the Life Cycle (Brown J.E., ed.)."Nutrition through the Life Cycle (Brown J.E., ed.), 325-354

- Swindale A, Bilinsky P (2006) Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS) for Measurement of Household Food Access: Indicator Guide.

- Belachew T, Lindstrom D, Gebremariam A, Hogan D, Lachat C (2013) Food Insecurity, Food Based Coping Strategies and Suboptimal Dietary Practices of Adolescents in Jimma Zone Southwest Ethiopia. Plos one 8: e57643.

- Belachew T, Hadley C, Lindstrom D, Gebremariam A, Lachat C (2011) Food insecurity, school absenteeism and educational attainment: longitudinal study. Nutr J 10:29

- Belachew T, Hadley C, Lindstrom D (2008) Differentials in measures of dietary quality among adolescents in Jimma zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J.

- Teshome T, Singh P, Moges D (2012) Prevalence and Associated Factors of Overweight and Obesity Among High School Adolescents in Urban Communities of Hawassa, Southern Ethiopia. Curr Res Nutr Food Sci Jour 1: 23-36.

- Alelign T, Degarege A, Erko B (2015) Prevalence and factors associated with under nutrition and anemia among school children in Durbete Town, northwest Ethiopia. Arch Public Health.

- Cappa C, Wardlaw T, Langevin-Falcon C, Diers J (2012) Progress for children-A report card on adolescents. Lancet 379: 232-235.

- UNICEF (2011) The state of the World’s children 2011: adolescence an age of opportunity.

- Williams S (2013) Action needed to combat food and drink companies' social media marketing to adolescents. Prosp Public Health 133:146-147.

- World Health Organization (2009) Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: Conclusions of a consensus meeting held 6-8 November 2007 in Washington, DC, USA. Geneva: WHO.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2007) Nutrition in adolescence: issues and challenges for the health sector: issues in adolescent health and development.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2003) Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases: Report of a joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. Geneva: WHO.

- Gebreyohannes Y, Shiferaw S, Demtsu B, Bugssa G (2014) Nutritional Status of Adolescents in Selected Government and Private Secondary Schools of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. J Nutri Food Sci 3:504-514.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Crossref

Citation: Haile A, Girma S, Dugassa D (2022) Effects Of Dietary Diversity and Eating Behaviors On Adolescent Girl’s Nutritional Status In Government Schools, Akaki Kality Sub City, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A School-Based Cross-Sectional Study. J Nutr Sci Res 7: 165. DOI: 10.4172/snt.1000165

Copyright: © 2022 Haile A. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 3834

- [From(publication date): 0-2022 - Nov 06, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 3176

- PDF downloads: 658