Research Article Open Access

Effect of Knowing Patients' Wishes and Health Profession on Euthanasia

Mireille Lavoie1,2*, Gaston Godin1, Lydi-Anne Vézina-Im1, Danielle Blondeau1, Isabelle Martineau3 and Louis Roy41Faculty of Nursing, Laval University, Québec, Canada

2Équipe de Recherche Michel-Sarrazin en Oncologie psychosociale et Soins palliatifs (ERMOS), Centre de recherche du CHU de Québec - Hôtel-Dieu de Québec, Canada

3Maison Michel-Sarrazin, Québec, Canada

4Hôpital de l’Enfant-Jésus du CHU de Québec, Québec, Canada

- *Corresponding Author:

- Mireille Lavoie

Faculty of Nursing, Laval University, Québec, Canada, G1V 0A6

Tel: 418-656-2131(8590)

Fax: 418-656-3920

E-mail: mireille.lavoie@fsi.ulaval.ca

Received date January 14, 2014; Accepted date February 22, 2014; Published date February 28, 2014

Citation: Lavoie M, Godin G, Vézina-Im LA, Blondeau D, Martineau I, et al. (2014) Effect of Knowing Patients’ Wishes and Health Profession on Euthanasia. J Palliat Care Med 4: 169. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.1000169

Copyright: © 2014 Lavoie M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine

Abstract

Background: Respecting patients’ autonomy is often put forward as one of the main reasons why certain health professionals are favourable to euthanasia. Few studies have compared whether nurses and physicians hold different beliefs regarding euthanasia. The objective of the study was to experimentally test whether knowing patients’ wishes and profession can affect health professionals’ intentions and beliefs regarding performing euthanasia. Methods: This a 2×2 random factorial design study (experimental conditions: patient’s wishes known or not; professions: nurses or physicians). A vignette describing the case of a person near death was used to manipulate knowledge of patient’s wishes. Random samples of nurses and physicians from the province of Québec, Canada, were obtained using random digit tables. Samples were weighted according to the domains of practice and medical specialties included in the study. Data were collected by means of an anonymous questionnaire based on an extended version of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Results: Overall, the response rate was 41.3%. There was a significant known wishes×profession interaction for intention, F (3, 266)=7.38, p=0.0070 and only a known wishes effect for the other beliefs, F (6, 256)=2.86, p=0.0102. Scores for intention and the other beliefs were lower among physicians who were exposed to the vignette where patient’s wishes were unknown. Conclusion: Knowing patients’ wishes regarding euthanasia appears to influence physicians, but not nurses. This is the first study to test whether knowledge of patient’s wishes and profession have an impact on health professionals’ intention and beliefs regarding euthanasia.

Keywords

Euthanasia; Patient autonomy; Nurses; Physicians; Intention

Background

Euthanasia remains a controversial topic in Canada. One of the major arguments in favour of euthanasia is that it supports the patient’s autonomy and expressed wishes [1-3]. Numerous studies confirm that end-of-life patients place a high level of importance on the respect of their autonomy and wish to decide “when” and “how” they die [4-6]. Unfortunately, these studies do not provide any information about whether patients’ wishes have an impact on health professionals’ intention to practise euthanasia.

Most studies either assess nurses’ or physicians’ attitude towards euthanasia. To our knowledge, only one study compared whether nurses and physicians hold different beliefs concerning euthanasia [7]. The results of this latter study indicated that nurses’ main reason for providing euthanasia was the pain and depression of the patient; while for physicians, it was the pain and depression of the patient and insufficient support. Reviews on the attitude of physicians and nurses toward euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide also either report results on nurses or on physicians [1-3,8-12]. Only one review was concerned with physicians’ and nurses’ attitude toward euthanasia, but the results were reported and discussed separately [13].

The purpose of the present study was thus to fill this gap in the literature by experimentally testing whether knowing patient’s wishes and health profession have an impact on health professionals’ intention and beliefs regarding euthanasia.

Theoretical framework

The study was guided by an extended version of the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB).The efficacy of the TPB [13] in predicting intentions to adopt various health behaviours, including among health professionals, and the key role of intentions to predict behaviours has already been clearly established in a number of meta-analyses [14-19]. Intention represents one’s motivation to adopt a given behaviour. Behaviour is predicted by intention and by perceived behavioural control when the context is less volitional. Intention, in return, is formed of the following three constructs: attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioural control (PBC). Attitude is an evaluation, either positive or negative, of the adoption of a given behaviour. In the present study, attitudes were evaluated by using its two components, cognitive and affective attitudes, as suggested by Triandis [20]. Cognitive attitude refers to instrumental consequences (e.g., useless/ useful) of the adoption of a given behaviour while affective attitude is rather concerned with emotional consequences (e.g., sad/happy). Subjective norm represents the perceived social pressure to adopt a given behaviour. PBC refers to people’s evaluation of their ability to adopt a given behaviour. External factors such as socio-demographic variables (e.g., age, gender) can also influence the intention to adopt a given behaviour through the other constructs.

New variables can be added to the TPB as long as they improve its predictive ability [21]. Given there is evidence that professional and moral norms are determinants of health professionals’ intention to adopt various behaviours [22-26], these two variables were added in the present study. Professional norm refers to the appropriateness of adopting a behaviour given one’s profession. Moral norm is a variable originating from the Theory of Interpersonal Behaviour [20] which is related to the appropriateness of adopting a given behaviour according to one’s personal and moral values. In terms of external factors, the following socio-demographic and contextual variables were assessed: number of end-of-life patients nurses and physicians cared for in the past year and the percentage of their practice they represented, whether they have relatives who received palliative care before their death, years of experience, worksite, age, gender, religious affiliation and attitude towards the legalisation of euthanasia in Canada.

Methods

Study design and participants

This is a 2×2 random factorial design study (experimental conditions: knowing patient’s wishes or not; health professions: nurses or physicians). Participants consisted of nurses and physicians from the province of Québec, Canada. Head nurses were excluded from the study since they do not work at the bedside of patients. Physicians and nurses with underage patients (e.g., paediatrics), patients with mental diseases (psychiatry), or whose job makes them unlikely to care for endof- life patients (e.g., rehabilitation, plastic surgery) were also excluded.

To obtain the two samples, nurses’ association and physicians’ medical association were contacted and they provided lists of their active members. Random samples of 445 nurses and 445 physicians were obtained using random digit tables. The samples were weighted according to the domains of practice and medical specialties included in the study to reflect as closely as possible their distribution in the province of Québec.

The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Centre hospitalier universitaire (CHU) de Québec.

Clinical vignettes: knowing patient’s wishes or not

The clinical vignettes were developed with the assistance of a nurse (IM) and a physician (LR) who have many years of experience in caring for end-of-life patients. Nurses and physicians working in palliative care were also recruited to 1) ensure that the vignettes adhered to clinical reality (2 nurses and 2 physicians); 2) ensure that the different clinical vignettes were well counterbalanced (4 nurses and 4 physicians); and 3) approve a preliminary version of the study questionnaire (5 nurses and 4 physicians).

There were two clinical vignettes, which both describe the case of a 70-year-old man, Mr Brown, who suffers from cancer that is now generalised and whose chemotherapy and radiotherapy treatments failed to stop the progression of the disease. The patient willingly stopped any curative or life-prolonging care and accepted palliative care. He is in a lot of pain that is partially responsive to analgesic treatment. His life expectancy is less than 10 days. His speech is now incoherent and he can no longer assume an active role in the decisions concerning his care. The only difference is that in one of the two versions, the patient made several explicit requests for euthanasia to the healthcare team while still apt, while in the other he never clearly expressed his wishes concerning euthanasia.

The psychometric qualities of the questionnaire were verified by means of a previous test-retest study. A total of 35 health professionals (17 nurses and 18 physicians) completed the entire questionnaire two times at a two-week interval. The questionnaire had good internal consistency with all alpha coefficients above 0.70 [27]. It also had good temporal stability with all intra-class coefficients above 0.70 [28].

Data collection

Data were collected by means of an anonymous self-administered questionnaire sent and returned by mail. All questionnaires were sent with a personalised letter presenting the project, a fact sheet and with a preaddressed prepaid envelope. A first reminder was sent by mail one week after the questionnaire and a second reminder was sent the following week (i.e., 2 weeks after questionnaire mailing) [29].

Questionnaire completion required between 15 and 20 minutes. The following definition of euthanasia was provided on the cover of the questionnaire: “an act which consists in intentionally causing the death of a person with an incurable disease”. Participants were instructed to answer the questions by referring to the clinical vignette as if they were responsible for a case similar to the one described and they were also reminded every two pages that the questions refer to a context in which the practice of euthanasia would be legally accepted. The illegality of euthanasia was taken out of the equation, following a previous study [30] that successfully applied this methodology, in order to reduce the impact of social desirability on participants’ decisions. All cognitive items were measured by means of 7-point Likert-type scales (strongly / somewhat / slightly disagree / neither disagree nor agree / slightly / somewhat / strongly agree), except cognitive and affective attitudes which were measured with 7-point semantic differential scales (e.g., very / somewhat / slightly inappropriate / neither one / slightly / somewhat / very appropriate).

Variables measured

Intention was measured with the following three items: 1) “My intention would be to practise an act of euthanasia in a case similar to Mr Brown’s” (strongly disagree / strongly agree); 2) “The chances that I practise an act of euthanasia in a case similar to Mr Brown’s would be…” (very low / very high); 3) “In a case similar to Mr Brown’s, I would practise an act of euthanasia” (strongly disagree / strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.88 for nurses and 0.96 for physicians and the two-week intra-class coefficient was 0.97 for nurses and 0.91 for physicians.

Perceived behavioural control was measured with the following three items: 1) “For me, practising an act of euthanasia in a case similar to Mr Brown’s would be…” (very difficult / very easy); 2) “It would be up to me to practise an act of euthanasia in a case similar to Mr Brown’s” (strongly disagree / strongly agree); 3) “I would be capable of practising an act of euthanasia in a case similar to Mr Brown’s” (strongly disagree / strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.84 for nurses and 0.83 for physicians and the two-week intra-class coefficient was 0.85 for nurses and 0.77 for physicians.

Cognitive attitude was measured with the following five items: “For me, practising an act of euthanasia in a case similar to Mr Brown’s would be… 1) very useless / very useful; 2) very harmful / very beneficial; 3) very unsafe / very safe; 4) very inappropriate / very appropriate; 5) very irrational / very rational”. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.94 for both nurses and physicians and the two-week intra-class coefficient was 0.94 for nurses and 0.90 for physicians.

Affective attitude was measured with the following three items: “For me, practising an act of euthanasia in a case similar to Mr Brown’s would be… 1) very guilt-ridden / very guilt-free; 2) very uncomfortable / very comfortable; 3) very unsatisfying / very satisfying”. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.91 for both nurses and physicians and the twoweek intra-class coefficient was 0.91 for nurses and 0.88 for physicians.

Subjective norm was measured with the following three items: 1) “Most people who are important to me would accept that I practise an act of euthanasia in a case similar to Mr Brown’s” (strongly disagree / strongly agree); 2) “If I practised an act of euthanasia in a case similar to Mr Brown’s, most people who are important to me would…” (strongly disagree / strongly agree); 3) “People of great importance to me think that I should practise an act of euthanasia in a case similar to Mr Brown’s” (strongly disagree / strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.93 for nurses and 0.94 for physicians and the twoweek intra-class coefficient was 0.95 for nurses and 0.90 for physicians.

Moral norm was measured with the following three items: 1) “Practising an act of euthanasia in a case similar to Mr Brown’s would be acting in accordance with my principles” (strongly disagree / strongly agree); 2) “My personal values would encourage me to practise an act of euthanasia in a case similar to Mr Brown’s” (strongly disagree / strongly agree); 3) “Practising an act of euthanasia in a case similar to Mr Brown’s would be compatible with my moral values” (strongly disagree / strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.94 for nurses and 0.96 for physicians and the two-week intra-class coefficient was 0.98 for nurses and 0.93 for physicians.

Professional norm was measured with the following item for nurses: “Practising an act of euthanasia in a case similar to Mr Brown’s would be compatible with my role as a nurse”. The same variable was measured with the following item for physicians: “Practising an act of euthanasia in a case similar to Mr Brown’s would be compatible with my role as a physician”. Given that professional norm was measured with a single item, no Cronbach’s alpha coefficient could be computed. The two-week intra-class coefficient was 0.95 for nurses and 0.90 for physicians.

Statistical analyses

A series of one-way analysis of variance (ANOVAs) and chisquare analyses were performed to verify potential socio-demographic differences between the groups. Differences in intention according to the patient’s wishes and health profession were verified by means of a 2×2 ANOVA. A series of Pearson correlations were also performed to verify if the socio-demographic variables were correlated with the dependent variables (intention and the other constructs). When a socio-demographic variable significantly correlated with a dependent variable (r>0.60) statistically differed (p<0.05) between the groups, it was added as a covariate in all the statistical analyses. The analyses were then compared with and without the covariates to verify if the results were the same. Differences in health professionals’ beliefs according to the patient’s wishes and health profession were identified by means of a 2×2 multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). The dependent variables for this latter analysis were perceived behavioural control, cognitive attitude, affective attitude, subjective norm, moral norm and professional norm. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) with a 0.05 alpha level.

Results

Sample characteristics and allocation checks

The overall response rate was 41.3% (44.2% for nurses and 38.3% for physicians), which is comparable to similar studies among health professionals [23,24,31,32]. The complete socio-demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. The results of the ANOVAs and chi-square analyses indicated that the groups did not differ in terms of the number of them who have relatives who received palliative care before their death, years of work experience, workplace and the number of them who have a religious affiliation (all ps>0.05). While there were some significant differences between the groups in terms of the number of end-of-life patients they cared for, the percentage of practice these patients represent, age, gender, and attitude towards the legalisation of euthanasia in Canada, none of these variables were significantly correlated to intention and the other constructs (all r ≤ 0.25), except attitude towards the legalisation of euthanasia in Canada which was significantly correlated to intention (r = 0.72) and the other constructs (all r ≥ 0.67).

| Variables | Means (standard deviation) / Percentages Vignettes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | No knowledge | p-value | |||

| Nurses (n = 80) |

Physicians (n = 58) |

Nurses (n = 73) |

Physicians (n = 59) |

||

| Cared for end-of-life patients Number Percentage of practice |

26.99 (44.02) 24.04 (25.92) |

35.00 (56.05) 12.58 (24.48) |

17.24 (16.90) 18.15 (21.55) |

20.68 (14.85) 7.65 (12.51) |

.0142 .0002 |

| Relatives received palliative care Yes |

52.50% | 46.94% | 51.39% | 47.37% | n.s. |

| Years of experience Less than 1 year Between 1-5 years Between 6-10 years Between 11-15 years Between 16-25 years More than 26 years |

0% 26.25% 22.50% 8.75% 16.25% 26.25% |

2.00% 26.00% 16.00% 6.00% 18.00% 32.00% |

4.17% 26.39% 26.39% 8.33% 12.50% 22.22% |

3.51% 26.32% 8.77% 12.28% 24.56% 24.56% |

n.s. |

| Workplace Hospital or hospital complex |

52.50% | 54.00% | 37.00% | 43.86% | n.s. |

| Age | 41.43 (11.57) | 47.08 (14.27) | 40.18 (11.15) | 44.40 (11.35) | .0014 |

| Gender Female |

92.50% | 48.00% | 86.11% | 52.63% | < .0001 |

| Religious affiliation Yes |

70.00% | 56.00% | 59.72% | 71.93% | n.s. |

| Attitude towards legalisation | 5.43 (1.92) | 4.91 (2.07) | 5.35 (1.82) | 4.36 (2.23) | .0028 |

Note. n.s.: non signifiant (p> 0.05)

Table 1: Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Sample.

Effect of knowing patients’ wishes and health profession on euthanasia

Overall, 103 nurses (67.32%) had a positive intention (score >4), 44 nurses (28.76%) a negative intention (score <4) and 6 nurses (3.92%) a neutral intention (score of 4) to practice euthanasia. When the patient’s wishes regarding euthanasia were known, 57 nurses (71.25%) expressed a positive intention, 20 nurses (25.00%) a negative intention and 3 nurses (3.75%) a neutral intention. When the patient’s wishes concerning euthanasia were unknown, 46 nurses (63.01%) reported a positive intention, 24 nurses (32.88%) a negative intention and 3 nurses (4.11%) a neutral intention.

Overall, 60 physicians (51.28%) had a positive intention (score >4), 54 physicians (46.16%) a negative intention (score <4) and 3 physicians (2.56%) a neutral intention (score of 4) to practice euthanasia. When the patient’s wishes regarding euthanasia were known, 41 physicians (70.69%) expressed a positive intention, 15 physicians (25.86%) a negative intention and 2 physicians (3.45%) a neutral intention. When the patient’s wishes concerning euthanasia were unknown, 19 physicians (32.20%) reported a positive intention, 39 physicians (66.10%) a negative intention and 1 physician (1.70%) a neutral intention.

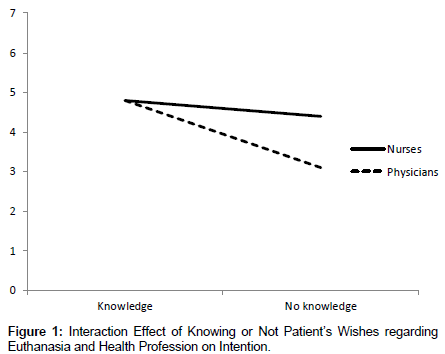

The results of the 2×2 ANOVA indicated that there was a significant known wishes×profession interaction for intention, F (3, 266) = 7.38, p = 0.0070 (Figure 1). The results were similar when controlling for attitude towards the legalisation of euthanasia in Canada (data not shown). Contrast analyses indicated that the level of intention was lower among physicians exposed to a vignette where the patient’s wishes regarding euthanasia were unknown (Table 2).

| Variables | Adjusted means (standard error) Vignettes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | No knowledge | |||

| Nurses (n = 80) |

Physicians (n = 58) |

Nurses (n = 73) |

Physicians (n = 59) |

|

| Intention | 4.80a (0.22) | 4.80a (0.25) | 4.39a (0.23) | 3.09b (0.25) |

| Perceived behavioural control | 4.19c (0.19) | 4.23c (0.24) | 3.74c(0.21) | 3.05d (0.23) |

| Cognitive attitude | 5.14e (0.17) | 5.25e (0.21) | 4.81e (0.18) | 4.19f (0.20) |

| Affective attitude | 4.31g (0.19) | 4.21g (0.23) | 3.96g (0.20) | 3.22h (0.22) |

| Subjective norm | 5.03i (0.20) | 5.04i (0.24) | 4.72i (0.21) | 3.78j (0.24) |

| Moral norm | 4.99k (0.23) | 4.99k (0.27) | 4.47k (0.24) | 3.48l (0.27) |

| Professional norm | 4.92m (0.24) | 5.05m (0.28) | 4.57m (0.25) | 3.67n (0.28) |

Note. The range of possible scores is from 1 to 7. A score between 1 and 4 is negative, a score of 4 is neutral and a score between 4 and 7 is positive. Adjusted means per row that do not share the same subscript differ significantly (p< .05)

Table 2: Adjusted Mean Scores for the Theoretical Constructs.

The results of the 2×2 MANOVA indicated that there was no significant interaction effect for the other constructs (F<1) and no significant health profession effect, F (6, 256) = 1.07, p = 0.3836, but a significant known wishes effect, F (6, 256) = 2.86, p = 0.0102. The results were similar when controlling for attitude towards the legalisation of euthanasia in Canada (data not shown). Contrast analyses indicated that the mean scores for all the cognitions were lower for physicians exposed to a vignette in which the patient’s wishes were unknown (Table 2).

Discussion

Knowing patients’ wishes regarding euthanasia seems important for physicians. When the patient’s wishes concerning euthanasia were known, 70.69% of physicians expressed a positive intention to practice this act, while when they were unknown, only 32.20% of physicians had a positive intention. Similarly, in a previous review of European physicians’ attitudes towards euthanasia, the right of the patient to decide about his/her own life and death was one of the reasons why physicians mentioned being favourable to euthanasia [2]. In the present study, when physicians did not know patient’s wishes, they were less motivated to practise euthanasia (intention), they negatively rated their ability to perform this act (perceived behavioural control), they perceived less positive consequences (cognitive attitude), they associated negative emotions with euthanasia (affective attitude), they perceived that their entourage would disapprove if they adopted this behaviour (subjective norm), they saw practicing euthanasia as incompatible with their personal values (moral norm) and with their professional role (professional norm).

In this study, knowing or not the patient’s wishes regarding euthanasia did not have a significant impact on nurses’ intention and beliefs concerning euthanasia. In fact, when the patient’s wishes concerning euthanasia were known, 71.25% of nurses reported a positive intention to perform this act compared to 63.01% of nurses when the patient’s wishes were unknown, a difference of less than 10%. This result is rather surprising given that previous reviews among nurses identified respecting patients’ autonomy as a central value [1,3]. This could mean that nurses who were exposed to the vignette in which the patient’s wishes are unknown had the intention to practise euthanasia with the aim to relieve the patient of his unappeasable pain. In this sense, it has been reported that sometimes healthcare providers are faced with conflicts between competing ethical principles, such as autonomy and beneficence [33,34]. In fact, according to Beauchamp and Childress [34], “whether respect for the autonomy of patients should have priority over professional beneficence directed at those patients is a central problem in biomedical ethics (p. 207).” As such, in one of our vignettes, these two ethical principles were well aligned whereas in the other, there was a matter of debate. In this latter context, health professionals were faced with making sure of respecting the patient’s autonomy, which was unknown, or relieving that person of refractory pain (beneficence). For nurses, the principle of beneficence might have overridden the absence of known wishes whereas among physicians, making sure of respecting patients’ autonomy was probably exerting a more important influence.

Strengths of the present study are the novelty of using a 2×2 random factorial design to verify the effect of knowing patients’ wishes and profession on health professionals’ intentions and beliefs regarding euthanasia and the rigorous methodology used to develop and validate the clinical vignettes and the questionnaire. Two limitations must be mentioned. First, the study response rate was low, although comparable to previous studies among health professionals. However, according to some authors, low response rates are more acceptable when the topic is controversial, such as in the case of euthanasia [35,36]. Second, there is no possibility to ensure that the two samples were truly representative of their respective professions. As such, this might be one of the reasons why we observed differences between the two professions. Nonetheless, the known potential confounding factors were controlled in the statistical analyses.

In conclusion, to our knowledge, this is the first study to experimentally test whether knowledge of patient’s wishes and health profession has an impact on health professionals’ intention and beliefs regarding euthanasia. It is also one of the few studies that compared nurses’ and physicians’ beliefs concerning euthanasia using a psychosocial theory and with a validated instrument.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ethics Office of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research [grant number EOG – 11392].The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution Steve Amireault, PhD, Laval University, for his advices on the statistical analyses.

References

- Verpoort C, Gastmans C, De Bal N, Dierckx de Casterlé B (2004) Nurses' attitudes to euthanasia: a review of the literature. Nurs Ethics 11: 349-365.

- Gielen J, Van Den Branden S, Broeckaert B (2008) Attitudes of European physicians toward euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: a review of the recent literature. J Palliat Care 24: 173-184.

- Quaghebeur T, Dierckx de Casterlé B, Gastmans C (2009) Nursing and euthanasia: a review of argument-based ethics literature. Nurs Ethics 16: 466-486.

- Bolmsjö I (2000) Existential issues in palliative care--interviews with cancer patients. J Palliat Care 16: 20-24.

- Carter H, MacLeod R, Brander P, McPherson K (2004) Living with a terminal illness: patients' priorities. J AdvNurs 45: 611-620.

- Volker DL, Kahn D, Penticuff JH (2004) Patient control and end-of-life care part II: the advanced practice nurse perspective. OncolNurs Forum 31: 954-960.

- Oz F (2001) Nurses' and physicians' views about euthanasia. ClinExcell Nurse Pract 5: 222-231.

- Dickinson GE, Clark D, Winslow M, Marples R (2005) US physicians' attitudes concerning euthanasia and physician-assisted death: A systematic literature review. Mortality10:43-52.

- McCormack R, Clifford M, Conroy M (2012) Attitudes of UK doctors towards euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: a systematic literature review. Palliat Med 26: 23-33.

- Berghs M, Dierckx de Casterlé B, Gastmans C (2005) The complexity of nurses' attitudes toward euthanasia: a review of the literature. J Med Ethics 31: 441-446.

- De Beer T, Gastmans C, Dierckx de Casterlé B (2004) Involvement of nurses in euthanasia: a review of the literature. J Med Ethics 30: 494-498.

- De Bal N, Gastmans C, Dierckx de Casterlè B (2008) Nurses' involvement in the care of patients requesting euthanasia: a review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud 45: 626-644.

- Emanuel EJ (2002) Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: a review of the empirical data from the United States. Arch Intern Med 162: 142-152.

- Armitage CJ, Conner M (2001) Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: a meta-analytic review. Br J SocPsychol 40: 471-499.

- Conner M, Sparks P (2005) The theory of planned behaviour and health behaviour. In: Conner M, Norman P (Eds.), Predicting Health Behaviour. (2nd edn.),Open University Press, Maidenhead.

- Godin G, Kok G (1996) The theory of planned behavior: a review of its applications to health-related behaviors. Am J Health Promot 11: 87-98.

- Webb TL, Sheeran P (2006) Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol Bull 132: 249-268.

- McEachan R, Conner M, Taylor NJ, Lawton R (2011) Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev 5:97-144.

- Godin G, Bélanger-Gravel A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J (2008) Healthcare professionals' intentions and behaviours: a systematic review of studies based on social cognitive theories. Implement Sci 3: 36.

- Triandis HC (1980) Values, attitudes and interpersonal behavior. NebrSympMotiv 27: 195-259.

- Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 50:179-211.

- Godin G, Vézina-Im LA, Naccache H (2010) Determinants of influenza vaccination among healthcare workers. Infect Control HospEpidemiol 31: 689-693.

- Daneault S, Beaudry M, Godin G (2004) Psychosocial determinants of the intention of nurses and dietitians to recommend breastfeeding. Can J Public Health 95: 151-154.

- Godin G, Beaulieu D, Touchette JS, Lambert LD, Dodin S (2007) Intention to encourage complementary and alternative medicine among general practitioners and medical students. Behav Med 33: 67-77.

- Côté F, Gagnon J, Houme PK, Abdeljelil AB, Gagnon MP (2012) Using the theory of planned behaviour to predict nurses' intention to integrate research evidence into clinical decision-making. J AdvNurs 68: 2289-2298.

- Chabot G, Godin G, Gagnon MP (2010) Determinants of the intention of elementary school nurses to adopt a redefined role in health promotion at school. Implement Sci 5: 93.

- Nunnally JC (1978) Psychometric theory (2nd Edn.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Fermanian J (1984) [Measuring agreement between 2 observers: a quantitative case]. Rev EpidemiolSantePublique 32: 408-413.

- Dillman DA, Smyth JD, Christian LM (2000) Internet, mail and mixed-mode surveys. The tailored design method. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, N.J.

- Young A, Volker D, Rieger PT, Thorpe DM (1993) Oncology nurses' attitudes regarding voluntary, physician-assisted dying for competent, terminally ill patients. OncolNurs Forum 20: 445-451.

- Blondeau D, Roy L, Dumont S, Godin G, Martineau I (2005) Physicians' and pharmacists' attitudes toward the use of sedation at the end of life: influence of prognosis and type of suffering. J Palliat Care 21: 238-245.

- Godin G, Naccache H, Fortin C (1998) Understanding physicians' intention to use a simple infection control measure: wearing gloves. Am J Infect Control 26: 413-417.

- Badger JM, Ladd RE, Adler P (2009) Respecting patient autonomy versus protecting the patient's health: a dilemma for healthcare providers. JONAS Healthc Law Ethics Regul 11: 120-124.

- Beauchamp TL, Childress JF (2009) Principles of biomedical ethics. (6th Edn.), Oxford University Press, New York.

- Sierles FS (2003) How to do research with self-administered surveys. Acad Psychiatry 27: 104-113.

- Rubenfeld G D (2004) Surveys: an introduction. Respir Care 49: 1181-1185.

Relevant Topics

- Caregiver Support Programs

- End of Life Care

- End-of-Life Communication

- Ethics in Palliative

- Euthanasia

- Family Caregiver

- Geriatric Care

- Holistic Care

- Home Care

- Hospice Care

- Hospice Palliative Care

- Old Age Care

- Palliative Care

- Palliative Care and Euthanasia

- Palliative Care Drugs

- Palliative Care in Oncology

- Palliative Care Medications

- Palliative Care Nursing

- Palliative Medicare

- Palliative Neurology

- Palliative Oncology

- Palliative Psychology

- Palliative Sedation

- Palliative Surgery

- Palliative Treatment

- Pediatric Palliative Care

- Volunteer Palliative Care

Recommended Journals

- Journal of Cardiac and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Palliative Care & Medicine

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Journal of Pediatric Neurological Disorders

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry: Open Access

- OMICS Journal of Radiology

- The Psychiatrist: Clinical and Therapeutic Journal

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 15266

- [From(publication date):

February-2014 - Feb 04, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 10819

- PDF downloads : 4447