Research Article Open Access

Effect of Enriched Artemia parthenogenetica with Probiotic (Bacillus spp.) on Growth, Survival, Fecal Production and Nitrogenous Excretion in Rainbow Trout(Oncorhynchus mykiss) Larvae

Jamali H1*, Tafi AA1, Jafaryan H2 and Patimar R2

1Department of Fishery, Urmia University, Urmia, Iran

2Department of Fishery, Gonbad University, Gonbad, Iran

- *Corresponding Author:

- Hadi Jamali

Department of Fishery

Urmia University, Urmia, Iran

Tel: 021-66568883

E-mail: saeed.jamali11@gmail.com

Received Date: February 22, 2014; Accepted Date: May 12, 2014; Published Date: May 25, 2014

Citation: Jamali H, Tafi AA, Jafaryan H, Patimar R (2014) Effect of Enriched Artemia parthenogenetica with Probiotic (Bacillus spp.) on Growth, Survival, Fecal Production and Nitrogenous Excretion in Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Larvae. J Fisheries Livest Prod 2:111. doi:10.4172/2332-2608.1000111

Copyright: © 2014 Jamali H, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Fisheries & Livestock Production

Abstract

This study was carried out to evaluate the effect of Probiotic (Bacillus spp.) on growth and survival rate and nitrogenous excretion in Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) larvae. Rainbow Trout larvae were fed on Artemia parthenogenetica nauplii enriched at suspension of five probiotic bacilli at doses of 0, 1×108, 2×108 and 3×108 (CFU l-1).The feeding level was 30 percent of total biomass per day. The daily ration was divided into four feeding portions. The end all the trout larvae were sampled for biometry and growth determination. Feces were collected twice a day by pipetting and ammonia and urea contents in each tank were determined. Results showed that, with the inoculating of probiotic Bacilli in suspension of broth, trout larvae survival and growth parameters generally increased. Fish larvae fed with enriched Artemia nauplii at dose of 2×108 CFU l-1 in suspension of broth had significantly higher survival and growth parameters than the control group (p<0.05). Ammonia excretion, urea excretion and fecal production decreased in experimental treatments (p<0.05). Then, our results confirm the potential of probiotic bacillus had promoted effects on enhancement of survival rate and growth performance in experimental treatments and probiotics can reduce ammonia and urea excretion in Rainbow trout larvae.

Keywords

Bacillus; Rainbow trout larvae; Bio-enrichment; Artemia parthenogenetica; Ammonia

Introduction

Rainbow trout culture is economically important in Iran and bacterial infectious disease in trout farming seems to be the major reason for decreasing the production level in some farms. Success and failure of fish culture programs are determined by early life stage conditions [1]. On the other hand, the occurrence of sub-clinical infections under farming conditions probably lead into reduced growth and increased mortality [2]. Probiotics are a cultured product or live microbial feed supplement, which beneficially affects the host by improving its intestinal balance and health of the host [3]. Most studies with probiotics conducted to date in fish have been undertaken with microbial strains isolated and selected from aquatic environments. There are a wide range of microalgae (Tetraselmis), yeast (Debaryomyces , Phaffia and Saccharomyces), gram positive (Bacillus, Lactococcus , Micrococcus, Carnobacterium, Enterococcus, Lactobacillus, Streptcoccus , Weisslla) and gram negative bacteria (Aeromonas, Alteromonas , Photorhodobacterium , Pseudomonas and Vibrio) that have been evaluated as a probiotic in aquaculture [4]. Probiotics in aquaculture have been shown to have several modes of action: competitive exclusion of pathogenic bacteria through the production of inhibitory compounds; improvement of water quality; enhancement of immune response of host species and enhancement of nutrition of host species through the production of supplemental digestive enzymes [5]. Because Bacillus bacteria secrete many exoenzymes [6], these bacteria have been used widely as putative probiotics. Some works have been done to evaluate competitive exclusion of potential probiotics on rainbow trout [7-9].

Stimulation of immune system in rainbow trout with several candidate probiotics has also been evaluated by some researchers [7,10-12]. The present study examined the effects of probiotic Bacillus spp. on growth and survival in Oncorhynchus mykiss larvae, when the Bacillus spp. were bioencapsulated within Artemia parthenogenetica.

Material and Methods

Preparing of probiotic Bacillus

The probiotic Bacillus was prepared from the commercial product Protexin aquatic (Iran-Nikotak), which is a blend of five Bacillus species. The blend of probiotic Bacilli (Bacillus licheniformis , B. subtilis , B. polymixa , B. laterosporus and B. circulans) from suspension of spores with special media were provided. Three concentrations of bacterial suspensions, 1×108, 2×108 and 3×108 bacteria per liter (CFU l-1) were provided by Protexin Co. and the colony forming unit (CFU) of probiotic Bacilli were tested by microbial culture in Tryptic Soy Agar (TSA) [13].

Artemia parthenogenetica removal and bioencapsulation

The Artemia parthenogenetica had been collected from the Lake Maharloo. The Artemia parthenogenetica were bioencapsulated in three doses of bacterial suspensions for 10 h at 29 ± 1oC, in glass con with 1 liter of seawater (30 gl-1 salinity) at a density of 2.0 g l-1 with constant illumination and oxygenated through by setting air pump [14]. The bioencapsulated nauplii were used as a vector to carry probiotic bacillus to digestive system of Oncorhynchus mykiss larvae. The Artemia parthenogenetica at a density of 2 g live Artemia litter-1 was held in a broth suspension with Bacillus licheniformis , B. subtilis , B. polymixa , B. laterosporus and B. circulans at densities of 1×108, 2×108 and 3×108 bacteria per liter for 10 hours.

Experimental design

This experiment was conducted in a completely randomized design with four treatments (three probiotic levels and a control), and three replicates per treatment for a total of twelve fiberglass tanks (each with a capacity of 10 liters). Larvae of Oncorhynchus mykiss (initial weight: 176 mg) were obtained from Hatchery of Zamiry center, Golestan, Iran. The density of fish larvae in per tank were 40 fish. Rainbow Trout larvae in control and experimental treatments were fed 30 percent of their body weight for 4 times a day (6.00, 12.00, 18.00 and 22.00).The control treatment was fed unbioencapsulated Artemia parthenogenetica. Water quality parameters of input water to rearing system were monitored each week throughout the experimental. The water temperature was 14 to 16°C, pH was 7.85 ± 0.26 and water oxygen level was maintained above 7.65 ± 0.55 mg l-1 during the experiment an electrical air pump.

Feces were collected twice a day by pipetting, oven dried at 70°C, weighed, at the beginning and end of which period, water was sampled, and ammonia and urea contents in each tank were determined by the method of Chaney and Marbach [15] and converted into energy by multiplying by 24.83 kJ g-1 for ammonia and 23.03 kJ g-1 for urea [16]. Potential loss of nitrogenous compounds through bacterial action or diffusion was quantified by setting controls without fish and the value was used to adjust determined nitrogenous excretion.

Sample collection

The fish were weighed individually at the beginning and at the end of the experiment. Before distributing fish to the experimental tanks (in the beginning of exogenous feeding), 10 fish were sampled from the holding tank for biometry. In the termination of experiment, 30 larvae from each tank were sampled and the final weight and length of body were measured.

Chemical analysis

Moisture contents of fish and feed were determined after oven-drying to constant weight at 105°C for diet and 70°C for fish [17]. Protein contents of fish and Artemia were measured by the Kjeldahl method using an auto Kjeldahl system. Lipid contents of fish and Artemia were measured by ether extraction. Ash contents of fish and Artemia were determined by a muffle furnace at 550°C for 8-10 h. Gross energy contents of fish and Artemia were measured by oxygen calorimetric bomb [18]. For each variable, at least duplicate samples were determined and the mean of duplicate determination was taken as the result when the relative deviation was less than 2%.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as Mean ± Standard deviation (SD). Data was transformed where necessary and statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS statistics version 15 for windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Il, USA) and accepted at the p<0.05 level. Data were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA. Significant differences between control and treatment groups were determined using post-hoc Fisher's Duncan test.

Results

Body chemical composition

The contents of Dry matter, protein, lipid, ash and energy in the body of Rainbow Trout at different treatments are listed in Table 2. A positive correlation to treatments was observed for the protein and Dry matter, and a negative correlation for lipid, ash contents and energy contents.

| Composition | A.parthenogenetica | O. mykiss |

|---|---|---|

| Dry matter | 11.76 | 17.04 |

| Crude protein | 39.09 | 72.05 |

| Crude lipid | 17.86 | 12.88 |

| Ash | 10.25 | 11.22 |

| Gross energy | 4592 | 4480 |

Table 1: Body chemical composition (g g−1 d.W.) and energy content (kJ g−1 d.W.) of Oncorhynchus mykiss larvae and Artemia parthenogenetica at beginning of the experiment.

| Dry matter | Crude protein | Crude lipid | Ash | Gross energy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 17.75 ± 1.00b | 72.90 ± 0.31c | 13.64 ± 0.58a | 12.82 ± 0.52a | 4565 ± 46.59a |

| 1×108 | 19.27 ± 1.59b | 74.05 ± 0.21b | 13.45 ± 0.23a | 12.18 ± 0.94a | 4483 ± 76.86a |

| 2×108 | 19.86 ± 2.94b | 75.39 ± 0.39a | 12.49 ± 0.32b | 11.98 ± 1.08a | 4402 ± 56.42b |

| 3×108 | 23.57 ± 1.40a | 75.66 ± 0.46a | 11.94 ± 0.37b | 11.68 ± 0.61a | 4389 ± 29.87b |

Table 2: Body chemical composition (g g−1 d.W.) and energy content (kJ g−1 d.W.) of larvae Rainbow Trout at different Treatment. (Values (mean ± SD) in the same row with different letters are significantly different (p<0.05)).

Nitrogenous excretion and fecal production

| Y | a | b | n | R2 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D.M | 17.40 | 0.18 | 12 | 0.89 | <0.01 |

| C.P | 73.06 | 0.096 | 12 | 0.94 | <0.01 |

| C.L | 13.79 | -0.061 | 12 | 0.95 | <0.01 |

| Ash | 12.71 | -0.036 | 12 | 0.94 | <0.01 |

| G.E | 4551 | -6.100 | 12 | 0.93 | <0.01 |

Table 3: Coefficients of the regression equation (Y=a+bRL) relating to Dry matter (g g−1 d.W.), Crude protein (g g−1d.W.), Crude lipid (g g−1 d.W.), Ash (g g−1 d.W.) and Gross energy (kJ g−1 d.W.) to Probiotic cells for larvae Rainbow Trout.

| Treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 1×108 | 2×108 | 3×108 | |

| 1SGRw | 5.98 ± 0.57c | 6.05 ± 0.62bc | 6.35 ± 0.57a | 6.17 ± 0.62b |

| 2SGRp | 6.47 ± 0.57c | 6.60 ± 0.63c | 6.95 ± 0.56a | 6.78 ± 0.57b |

| 3SGRd | 6.50 ± 0.57d | 6.83 ± 0.62c | 7.22 ± 0.56b | 7.57 ± 0.57a |

| 4SGRe | 5.97 ± 0.57b | 5.99 ± 0.63b | 6.23 ± 0.57a | 6.04 ± 0.57b |

| 5FCEw | 71.63 ± 2.27c | 73.66 ± 4.58bc | 80.77 ± 4.76a | 76.31 ± 5.17b |

| 6FCEp | 117.03 ± 12.90c | 122.98 ± 17.63c | 139.22 ± 18.48a | 131.14 ± 19.37b |

| 7FCEd | 94.81 ± 8.53d | 107.41 ± 8.53c | 123.11 ± 14.94b | 139.65 ± 20.41a |

| 8FCEe | 61.58 ± 4.23b | 62.98 ± 3.98b | 67.06 ± 4.15a | 62.58 ± 4.50b |

| 9HIS | 1.24 ± 0.34a | 1.43 ± 0.44a | 1.36 ± 0.49a | 1.35 ± 0.45a |

| 10VIS | 9.69 ± 1.85a | 9.42 ± 1.54ab | 9.38 ± 1.59ab | 8.74 ± 1.75b |

1SGRw=100×[ln(final body weight)−ln(initial body weight)] / days

of the experiment.

2SGRp=100×[ln(final body weight×final protein content)−ln(initial

body weight×initial protein content)] / days of the experiment.

3SGRd=100×[ln(final body weight×final dry matter content)

−ln(initial body weight×initial dry matter content)] / days of the

experiment.

4SGRe=100×[ln(final body weight×final energy content)−ln(initial

body weight×initial energy content)] / days of the experiment.

5FCEw=100×(final body weight−initial body weight) / feed intake.

6FCEp=100×[(final body weight×final protein content)−(initial

body weight×initial protein content)] / (feed intake×protein content).

7FCEd=100×[(final body weight×final dry matter content)−(initial

body weight×initial dry matter content)] / (feed intake×dry matter

content).

8FCEe=100×[(final body weight×final energy content)−(initial body

weight×initial energy content)] / (feed intake×energy content).

9Hepatosomatic index (HSI) = (Liver weigh/body weight) ×100.

10Viserosomatic index (VSI) = (Viseral weight /body weight) ×100.

Table 4: Specific growth rate in wet weight (SGRw, % day−1), dry weight (SGRd, % day−1), protein (SGRp, % day−1) and energy (SGRe, % day−1) and feed conversation efficiency in wet weight (FCEw, %), dry weight (FCEd, %), protein (FCEp, %) and energy (FCEe, %) of larvae Rainbow Trout at different Treatment (% per day). (Values (mean ± SD) in the same row with different letters are significantly different (p<0.05)).

| Treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 1×108 | 2×108 | 3×108 | |

| CN(Consumed nitrogen‚ mg N kgˉ dayˉ) | 778 | 778 | 778 | 778 |

| EI(Energy intake‚ KJ Kgˉ dayˉ) | 2388 | 2388 | 2388 | 2388 |

| Ammonia-nitrogen(mg NH3-N Kgˉ dayˉ) | 74.32 ± 2.28a | 67.10 ± 5.1ab | 51.32 ± 0.00b | 54.91 ± 4.3b |

| Urea-nitrogen(mg Urea-N Kgˉ dayˉ | 18.58 ± 0.57a | 16.78 ± 2.75ab | 12.83 ± 0.00b | 13.73 ± 1.07b |

| Total nitrogen(mg N Kgˉ dayˉ) | 92.9 ± 2.5a | 83.88 ± 8.01ab | 64.15 ± 0.00b | 68.63 ± 5.39b |

| Waste Energy- Ammonia | 1845 ± 56.74a | 1666 ± 27.39ab | 1247 ± 15.10b | 1363 ± 10.71b |

| Waste Energy- Urea | 427.91 ± 13.15a | 386.35 ± 63.53ab | 295.48 ± 11.10b | 316.12 ± 24.13b |

| Retained fecal | 3.46 ± 0.06a | 2.87 ± 0.03b | 2.23 ± 0.04d | 2.67 ± 0.04c |

| Total Waste Energy(%) | 89.01a | 80.35ab | 60.40b | 65.75b |

Table 5: Nitrogenous excretion (u, mg g−1 d−1) and faecal production (f, mg g−1 d−1 ) of larvae Rainbow Trout at different treatments. (Values (mean ± SD) in the same row with different letters are significantly different (p<0.05)).

Ammonia excretion, Urea excretion and fecal production decreased in experimental treatments when larvae were fed by bioencapsulated Artemia parthenogenetica (Table 5). The higher rate of Nitrogenous excretion and fecal production were observed in control treatment (p<0.05). One-way ANOVA showed that ammonia excretion, Urea excretion and fecal production was affected significantly by probiotic bacillus and least rate observed in 2×108 treatment (ammonia excretion: 51.32, p<0.05; Urea excretion: 12.83, p<0.05; fecal production: 2.23, p<0.05).

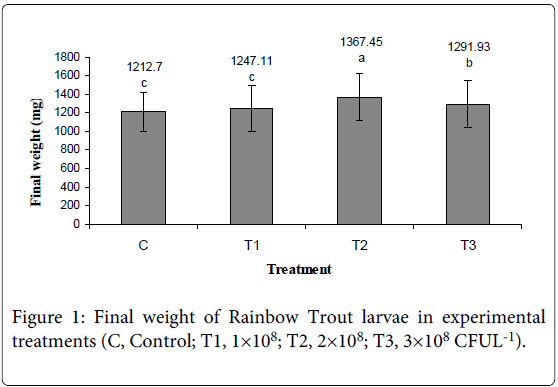

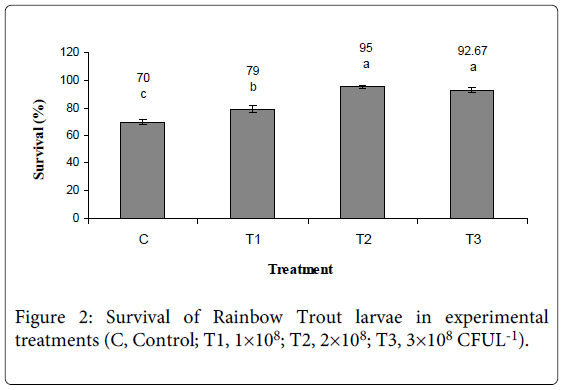

Final weight, Survival, Specific growth rate and feed conversion efficiency

Final weight, Survival, Specific Growth Rate in Wet Weight (SGRw), Dry Weight (SGRd), Protein (SGRp) and Energy (SGRe) of larvae Rainbow Trout increased in experimental treatments (Figure 1, 2 and Table 4). ANOVA showed that Final weight, Survival, Specific growth rate was affected significantly by probiotic bacillus and higher rate observed in 2×108 and 3×108 (CFU l-1) treatment (SGRw: 6.35, p<0.05; SGRd: 7.57, p<0.05; SGRp: 6.95, p<0.05; SGRe: 6.23, p<0.05).

Feed conversion efficiency in wet weight, dry weight, protein and energy of larvae Rainbow Trout also increased in experimental treatments and were highest at 2×108 and 3×108 (CFU l-1) treatment (Table 4).

Discussion

Final weight, Survival and Specific growth rate was affected significantly by probiotic bacillus and higher rate observed in 2×108 CFUL-1 treatment. The advantages of using probiotics in fish aquaculture were recently reviewed by Nayak [19] and Qi et al. [20]. The main beneficial effects of probiotic use in fish aquaculture are growth performance improvement [21,22] and disease control through immunity enhancement [19,20,23] and pathogens exclusion [20]. The bacteria could also have improved digestive activity via synthesis of vitamins and cofactors or via enzymatic improvement [4]. Among probiotics, Bacillus strains have become more and more popular and widely used in fish aquaculture [19,20,24]. In the use of live prey, Artemia nauplii are widely recognized as the best natural storable live feed available and are extensively used in marine finfish and crustacean hatcheries throughout the world because of their nutritional and operational advantages [25,26] and have been used as a vector for the carrying of different materials, including probiotics [27].

In this study, Artemia parthenogenetica were used as a vector to carry the probiotic Bacillus to the digestive tract of Rainbow Trout larvae. The probiotics in this experiment promoted the feeding and growth parameters in Rainbow Trout larvae in experimental treatments in comparison to control treatment. Effects of commercial probiotic on aquaculture has been investigated by researchers, and some of this research has not shown any positive effects on growth parameters or survival rate or any promising result on the cultural condition. For instance, Shariff et al. [28] found that treatment of Penaeus monodon with a commercial Bacillus probiotic did not significantly increase survival. These results disagree with our findings.

Results of all the probiotic treatments showed better growth performance and feeding parameters than the control. The beneficial effect of probiotic Bacillus sp. on the feeding efficiency of Rainbow Trout larvae was completely observed. The results indicated that the probiotic bacillus had significantly effects on the growth and feeding parameters in experimental treatments. The better body weight and SGR for weight, protein and energy were obtained in experimental treatments also better Feed conversion efficiency in wet weight, dry weight, protein and energy of larvae Rainbow Trout were obtained in experimental treatments. Similar finding were observed by Gatesoupe [29] in using Bacillus toyoi on turbot (Scophthalmus maximus), Swain et al. [30] in Indian carps that improved the growth factors and feeding performance and Ghosh et al. [31] on the Rohu. Bagheri et al. [32] found that supplementation of trout starter diet with the proper density of commercial Bacillus probiotic could be beneficial for growth and survival of rainbow trout fry. This finding agrees with our results. Ghosh et al. [1] indicated that the B.circulans, B. subtilis and B. pamilus, isolated from the gut of Rohu, have extracellular protease, amylase, and cellulose and play an important role in the nutrition of Rohu fingerlings. The photosynthetic bacteria and Bacillus sp. (isolated from the pond of common carp) was used in diet of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) by Yanbo and Zirong [33]. The results indicated that this probiotics increased growth parameters and digestive enzyme activities. Gram-positive bacteria, including members of the genus Bacillus, secret a wide range of exoenzymes [6], which might have supplied digestive enzymes and certain essential nutrients to promote better growth. Bacillus subtilis and B. leicheniformis can break down proteins and carbohydrates [34,35]. So it can be suggested that administration of Bacillus bacteria to trout fry results in enhanced digestion of food and improved growth [32].

There were significant (p <0.05) differences in dry matter, crude protein and crude lipid of O. mykiss between experimental treatments and control. Crude lipid and Gross energy were decreased in experimental treatments while crude protein was increased. Results showed that crude lipid and moisture of Rainbow Trout decreased in experimental treatments after feeding with probiotic while crude protein were increased [32,36]. El-dakar [37] reported that use of a dietary probiotic/prebiotic on Spinefoot rabbitfish (Siganus rivulatus) Although significant differences in moisture level and crude protein proportion are apparent among treatments, they do not follow a trend and thus suggest that variations among results are probably due to inherent variation associated with using wild undomesticated gene stock in research. However, results suggest a positive correlation between NEM supplementation and lipid concentration of the carcass.

Ammonia excretion, urea excretion and fecal production decreased in experimental treatments when larvae were fed by bioencapsulated Artemia parthenogenetica. Faramarzi [38] showed that ammonia and urea excretion were decreased in experimental treatments by inclusion of the probiotic bacilli in comparison with control treatments in Acipenser percicus larvae. Ammonia excretion rates are directly related to dietary nitrogen and protein intake in teleosts [39,40]. Increasing the dietary level of non-protein, digestible energy increases nitrogen retention by decreasing nitrogen losses [41,42]. The decrease in NH3-N concentration in this study appears to be the result of increased incorporation of ammonia into microbial protein, and may be the direct result of stimulated microbial activity [43]. Lashkarboloki [44] showed that enrichment of daphnia with Saccharomyces cerevisiae extract (Amax) probiotics can reduce ammonia and urea excretion and also cause increase protein retention in Acipenser percicus larvae body notably. The results of these studies showed that the blend of bacterial probiotics can increase the growth and feeding efficiency and also decrease ammonia and urea excretion in fish of experimental treatments in comparison of control.

References

- Ghosh K, Sen SK, Ray AK (2002) Growth and survival of Rohu, Labeorohita (Hamilton) spawn fed diets supplemented with fish intestinal microflora. ActaIctholPiscat 32: 83-92.

- Kapetanovic D, Kurtovic B, Teskeredzic E(2005) Difference in bacterial population in raibow trout (Onchorhynchusmykiss, Walbaum) fry aftertransfer from incubator to pools. FTB 48:189-193.

- Fuller R (1989) Probiotics in man and animals. J applbacteriol 66: 365-378.

- Gatesoupe FJ (1999) The use of probiotics in aquaculture. Aquaculture 180: 147-165.

- Verschuere L, Rombaut G, Sorgeloos P, Verstraete W (2000) Probiotic bacteria asBiological Control Agents in Aquaculture. MicrobiolMolBiol R 64: 655-671.

- Moriarty DJW (1998) Control of luminous vibrio species in penaeid aquaculture ponds. Aquaculture 164: 351-358.

- Nikoskelainen S, Ouwehand AC, Bylund G, Salminen S, Lilius EM (2003) Immune enhancement in rainbow trout (Onchorhynchusmykiss) by potential probiotic bacteria (Lactobacillus rhamnosus). Fish Shelfish. Immunol 15: 443-452.

- Irianto A, Austin B (2003) A short communication:use of dead probiotic cells to control furunculosis inrainbow trout, Onchorhynchusmykiss (Walbaum). JFish Dis 26:59-62.

- Ibrahim F, Quwehand AC, Salminen SJ (2004) Effect of temperature on in vitro adhesion of potential fish probiotics. MicrobEcol Health D 16: 222–227.

- Irianto A, Austin B (2002) Probiotic inaquaculture. J Fish Dis 25: 1-10.

- Panigrahi A, Kiron V, Kobayashi T, PuangkaewJ, Satoh S et al. (2004) Immune responses inrainbow trout, Onchorhynchusmykiss, induced by apotential probiotic, Lactobacillus rhamnosus JCM1136. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol VII. 102: 379-388.

- Kim DH, Austin B, (2006) Innate immune responses in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchusmykiss, Walbaum) induced by probiotics. Fish Shellfish Immun 21(5): 513–524.

- Rengpipat S, Phianphak W, Piyatiratitvorakul S, Menasveta p (1998) Effects of probiotic bacterium on black tiger shrimp Penaeusmonodon survival and growth. Aquaculture 167:301-313.

- Gomez Gil B, Herrera Vega MA, AberuGrobis FA, Roque A (1998) Bio-encapsulation oftwo different vibrio species in nauplii of the Brineshrimp (Artemiafransiscana). Appl. Environ.Microbiol 64 : 2318-2322.

- Chaney AL, Marbach EP (1962) Modified reagents for determination of urea and ammonia. ClinChem 8: 130–132.

- Elliot JM (1976) Energy losses in the waste products of brown trout (Salmotrutta L.). J AnimEcol 45: 561–580.

- Azewedo PA, LeesonS, ChoCY, Bureau, DP (2004) Growth and feed utilization of size rainbow trout (Onchorhynchusmykiss) and Atlantic salmon (Salmosalar)reared in fresh water: diet and species effects,and responses over time. AquacultNutr 10:401-411.

- Sorensen M, Storebakken T, ShearerKD (2005) Digestibility, growth and nutrient retention in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchusmykiss) fed diets extruded at two different temperatures.Aquaculture Nutrition 11:251-256.

- Nayak SK (2010) Probiotics and immunity: a fish perspective. Fish Shellfish Immunol 29: 2-14.

- Qi ZZ, Zhang XH, Boon N, Bossier P (2009) Probiotics in aquaculture of China d current state, problems and prospect. Aquaculture 290: 15-21.

- Ghosh S, Sinha A, Sahu C (2008) Dietary probiotic supplementation in growth and health of live-bearing ornamental fishes. AquacNutr 14: 289-99.

- Merrifield DL, Dimitroglou A, Bradley G, Baker RTM, Davies SJ (2009) Probiotic applications for rainbow trout (OncorhynchusmykissWalbaum) I. Effects on growth performance, feed utilization, intestinal microbiota and related health criteria. Aqua Nutr 16:504-510.

- Merrifield DL, Bradley G, Baker RTM, Davies SJ (2009) Probiotic applications for rainbow trout (OncorhynchusmykissWalbaum) II. Effects on growth performance, feed utilization, intestinal microbiota and related health criteria postantibiotic treatment. Aqua Nutr 16:496- 503.

- Aly SM, Mohamed MF, John G (2008) Effect of probiotics on the survival, growth and challenge infection in Tilapia nilotica (Oreochromisniloticus). Aquac Res 39: 647-656.

- Lavens P, Sorgeloos P (1996) Manual on the production and use of live food for aquaculture. FAO, Rome, Italy.

- Talpur AD, Memon AJ, Khan MI, Ikhwanuddin M, Danish Daniel MM et al. (2012) Effects of Lactobacillus Probiotics on the Enhancement of Larval Survival of Portunuspelagicus (Linnaeus, 175) Fed Via Bioencapsulated in Live Feed. World Journal of Fish and Marine Sciences 4 (1): 42-49.

- Gatesoupe FJ (1994) Lactic acid bacteria increase the resistance of turbot larvae, Scophthalmusmaximus, against pathogenic Vibrio. Aquat Living Resour 7: 277-282.

- Shariff M, Yusoff FM, Devaraja TN, SrinivasaRao SP (2001) The effectiveness of a commercial microbial product in poorly prepared tiger shrimp, Penaeusmonodon (Fabricius), ponds. Aquac. Res 32: 181–187.

- Gatesoupe FJ (1991) Bacillus sp. Spores: A new tool against early bacterial infection in turbot larvae, Scophthalmusmaximusln: larvens, p., Jaspers, E., Roelands, I. (Eds),Larvi–fish and crustacean larviculture symposium. European Aquaculture Society,Gent, pp. 409-411.

- Swain SK, Rangacharyulu PV, Sarkar S, Das KM (1996) Effect of a probiotic supplement on growth, nutrient utilization and carcass composition in mrigal fry. J Aquacult 4: 29-35.

- Ghosh k, SenSk, Ak Ray (2003) Supplementation of an isolated fish gut bacterium, Bacillus circulans, in Formulated diets for Rohu, Labeorohita, Fingerlings. Aquaculture - Bamidgeh 55(1): 13-21.

- BagheriT, Hedayati SA, Yavari V, Alizade M, Farzanfar A (2008) Growth, Survival and Gut Microbial Load of Rainbow Trout (Onchorhynchusmykiss) Fry Given Diet Supplemented with Probiotic during the Two Months of First Feeding. Turk J Fish AquatSc 8: 43-48.

- Yanbo W, Zirong X (2006) Effect of probiotic forcommom carp (Cyprinuscarpio) based on growthperformance and digestive enzymes activities. AnimFeed SciTechnol 127: 283-292.

- Rosovitz MJ, Voskuil MI, Chambliss GH (1998) Bacillus. In: A. Balows and B.I. Duerden (Eds), Systematic Bacteriology. Arnold Press, London.

- Farzanfar A (2006) Mini review paper: The use of probiotics in shrimp aquaculture. FemsImmunol Med Mic 48: 149-158.

- Sealey WM, Barrows FT, Smith CE, Overturf K, LaPatra SE (2009) Soybean meal level and probiotics in first feeding fry diets alter the ability of rainbow trout Oncorhynchusmykiss to utilize high levels of soybean meal during grow-out. Aquaculture 293: 195–203.

- El-Dakar AY, Shalaby SMM, Saoud IP (2007) Assessing the use of a dietary probiotic/prebiotic as an enhancer of spinefootrabbitfishSiganusrivulatus survival and growth. AquacultNutr 13: 407–412.

- Faramarzi M, Jafaryan H, Roozbehfar R, Jafari M, Biria M (2012) Influences of probiotic bacilli on ammonia and urea excretion in two conditions of starvation and satiation in persian sturgeon (Acipenserpersicus) larvae. Global Veterinaria 8 (2): 185-189.

- Rychly J (1980) Nitrogen balance in trout: II. Nitrogen excretion and retention after feeding diets with varying protein and carbohydrate levels. Aquaculture 20:343-350.

- Beamish FWH, Thomas E (1984) Effects of dietary protein and lipid on nitrogen losses in rainbow trout, Salmogairdneri. Aquaculture 41: 359-371.

- Kaushik SJ, Oliva-Teles A (1985) Effects of digestible energy on nitrogen and energy balance in rainbow trout. Aquaculture 50:89-101.

- Medale F, Brauge C, Vallee F, Kaushik SJ (1995) Effects of dietary proteinrenergy ratio, ration size dietary energy source and water temperature on nitrogen excretion in rainbow trout. Water SciTechnol 31:185-194.

- Harrison GARW, Hemken KA, Dawon R, Harmon J, Barker KB (1988) Influence of addition of yeast culture supplement to diets of lactating cows on ruminal fermentation and microbial populations. J. Dairy Sci 71:2967-2975.

- Lashkarbolouki M, Jafaryan H, Faramarzi M, Zabihi A, Adineh H (2011) The effect of feeding with Saccharomyces cerevisiae extract (Amax) on ammonia and urea excretion in Persian sturgeon (Acipenserpersicus) larvae by bioenrichment of Daphnia magna. Journal of research in Biology 2: 110-115.

Relevant Topics

- Acoustic Survey

- Animal Husbandry

- Aquaculture Developement

- Bioacoustics

- Biological Diversity

- Dropline

- Fisheries

- Fisheries Management

- Fishing Vessel

- Gillnet

- Jigging

- Livestock Nutrition

- Livestock Production

- Marine

- Marine Fish

- Maritime Policy

- Pelagic Fish

- Poultry

- Sustainable fishery

- Sustainable Fishing

- Trawling

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 16058

- [From(publication date):

June-2014 - Jul 12, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 11277

- PDF downloads : 4781