Review Article Open Access

Educational Programs for Family Caregivers in Palliative Care: A Literature Review

Carla Reigada1,2*, José Luís Pais-Ribeiro1 and Ana Novellas3,41Psychology and Educational Sciences Faculty, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

2Palliative Care Service São João Hospital Centre, Porto, Portugal

3University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain

4Catalan Institute of Oncology, Barcelona, Spain

- *Corresponding Author:

- Carla Reigada

Palliative Care Service, Centro Hospitalar de São João

EPE, Alameda Prof. Hernâni Monteiro, 4200 Porto, Portugal

Tel: 351963159800

E-mail: reigadacarla@gmail.com

Received date: July 29, 2014; Accepted date: October 31, 2014; Published date: November 8, 2014

Citation: Reigada C, Pais-Ribeiro JL, Novellas A (2014) Educational Programs for Family Caregivers in Palliative Care: A Literature Review. J Palliat Care Med 4:195. doi:10.4172/2165-7386.1000195

Copyright: 2014 Reigada C, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Palliative Care & Medicine

Abstract

Aim: To analyse the literature about educational programs aimed towards empowering caregivers of patients in palliative care (PC) attending to the conceptual difference between programs and psychosocial interventions. Method: Review of the literature published in English, Portuguese and Spanish languages between 01/2009 and 12/2013, supported by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines; PubMed, Scopus and SciELO were searched for studies about caregiver training programs developed in the PC field. 43 Palliative Care Associations listed in the European Association of Palliative Care (EAPC) PC ATLAS were contacted in order to complement this literature review. Results: Eight studies were identified and analysed concerning subject matter, measurement instruments, location, results, strategy and duration of the programs. All educational programs addressed issues related to the context of end of life; Program duration ranged from three weeks to two years, and took place in the community and in hospital or PC centres; all programs evaluated their respective impact using various measurement instruments. Conclusions: This review testifies the lack of publications regarding programs designed and developed to support family caregivers in PC. It is shown that caregivers benefit from support groups and educational programs to promote information and caregiver training, but perhaps the lack of funding for this kind of interventions can affect the caregiver’s treatment.

Keywords

Palliative care; Caregivers; Educational programs; Empowerment

Introduction

Background

“We cannot take away the whole hard thing that is happening, but we can help bring the burden into manageable proportions”. This sentence by Cicely Saunders [1] pinpoints the central objective of this study. Concern about providing support to the family caregiver was already manifested in the 1960's in multiple concepts which are at the basis of palliative care (PC) philosophy and principles. Society, which up until then widely admitted that care giving was an innate ability, especially when assigned to women, gradually began to reflect on this role and challenge health professionals to care for caregivers of end of life patients.

The training of care giving skills has become a particular priority in the context of PC, a concern which is visible in the increasing number of studies published in recent times. However, it should be noted that only in a few developed countries is this need really addressed with effective/formal support programs for caregivers.

Hudson et al. [2] did a systematic review of the literature within a 10 year time frame to identify psychosocial interventions directed towards patient’s families in PC. In this study the authors conceptualized some types of psychosocial support, educational programs, coping strategies, practical skills training, sleep assistance and family conferences as psychosocial interventions. Of the 713 articles initially identified, 14 were selected and the authors found that individual interventions seem to have few benefits for caregivers. In this sense, a group educational program reinforcing the same idea was developed by Hudson et al. [3] to promote the wellbeing of caregivers. The authors concluded that psychosocial interventions enhance the caregivers’ quality of life, but in fact group interventions can have a greater effect on the caregivers’ wellbeing and in solving their everyday problems.

To create a caregiver educational program is identical to create a preventive and creative project to promote positive aspects of care giving and cause a positive impact in their life. It is also crucial to develop instruments aimed at detecting a specific need or disability of the caregiver, objective and easy-to-apply, in order to invite the caregiver to work that specific skill. In other words, the main goal this kind of educational programs should focus on training specifics skills with the caregiver.

Demirbag [4] published a study about the impact of educational programs for relatives of cancer patients. Some assessment scales such as the Perceived Social Support from Family and Friends (PSS/FR, PSS/FA), Scale of Perceived Social Support (PSS) and an evaluation questionnaire focused on the emotional and social issues were used. All these questionnaires were administered previously to the start of the program. The program was based on regular home visits, twice a week, for basic home care which lasted an average of 2 hours, and demonstrated a positive impact on the participants' perceptions regarding the social support they received.

Tufan et al. [5] also focused on this issue and questioned whether educational programs for the family were truly useful. Their study showed that courses for caregivers can prove to be very necessary, if only for the simple fact that the mortality rate is stagnating.

Hudson et al. [6] challenged researchers and practitioners to focus on some key questions, which we have brought into the context of PC: how can psychosocial interventions be considered effective when they mostly occur over a short period of time? What is the best way to determine that a caregiver is in need of a specific intervention? What are the priorities and methods that should be developed and tested in a group of caregivers? Future projects must focus on psychosocial intervention of the caregiving family and clearly define their goals, discerning the general and specific needs, because joint intervention sessions are increasingly done with no concern towards the specific needs of each individual element. How many of us would feel likely to attend a session on a specific topic about which we have little or no interest?

With this in mind we set about analysing the existing literature on support programs directed towards caregivers in PC.

Method

A literature review was undertaken of the articles published in English, Portuguese and Spanish languages between 01/01/2009 and 31/12/2013, in the PubMed, Scopus and SciELO electronic databases with the following set of keywords: ((Palliative care [Title/Abstract]) OR Hospice [Title/Abstract]) AND Family [Title/Abstract]) OR caregivers [Title/Abstract]) AND Education [Title/Abstract]) AND Programs [Title/Abstract]. EndNote X7 and Excel computer software were used to organize the collected data.

All the original research articles published in scientific journals which studied a PC caregiver population over 18 years of age were included. Paediatric studies, books, doctoral and/or master's degree theses, case studies and literature reviews were excluded, as well as duplicate articles. The quality of each individual article was assessed according to the method presented by Hawker et al. [7]. All articles were selected, analysed and rated according to their quality by two independent reviewers, and by a third one in the case of doubt or lack of consensus.

In order to further enrich this review, 43 Palliative Care Associations listed in the European Association of Palliative Care (EAPC) PC ATLAS (http://www.eapc-taskforce-development.eu/tfdocs.php) were contacted via email and requested for their cooperation by answering the following question:

Are there educational programs in your country that are directed towards the families of hospice/end-of-life patients? If yes, in which hospices/palliative care teams are they running?

Article selection

Shortlisting of the articles occurred in three separate steps according to the criteria described above and based on the main research question: What programs do exist which are directed to family caregivers in PC?

First, the primary reviewer examined the titles of all the identified articles, selecting those which proved relevant to the study. Secondly, two independent reviewers analysed the abstracts and finally the selected articles which seemed to answer the research question were read in their entirety.

Defining the concepts

The following definitions were taken into account for the present study:

Interventions: psychotherapeutic actions to address a certain dimension, placed in the context of support to caregivers in PC.

Programs: set of multidisciplinary interventions delivered by PC teams, outlined for a period of time and targeted to caregivers.

Caregivers: relatives and/or friends directly or indirectly involved in unpaid patient caregiving.

Article type and Rating

Rating and quality assessment of the studies was based on the instrument developed by Hawker et al. [7] used for both quantitative and qualitative research articles. This instruments enables rating an article on a scale of 1 to 4 (1 "very poor", 2 "poor", 3 "satisfactory", 4 "good"), evaluating nine parameters: title and abstract, introduction and objectives, methods and data, sample, data analysis, ethics and bias, results, universality, and implications and utility. The adding of the scores resulting from each parameter will lead to a value in between 9 and 36 (9 "Very poor”, 36 "Good").

Results

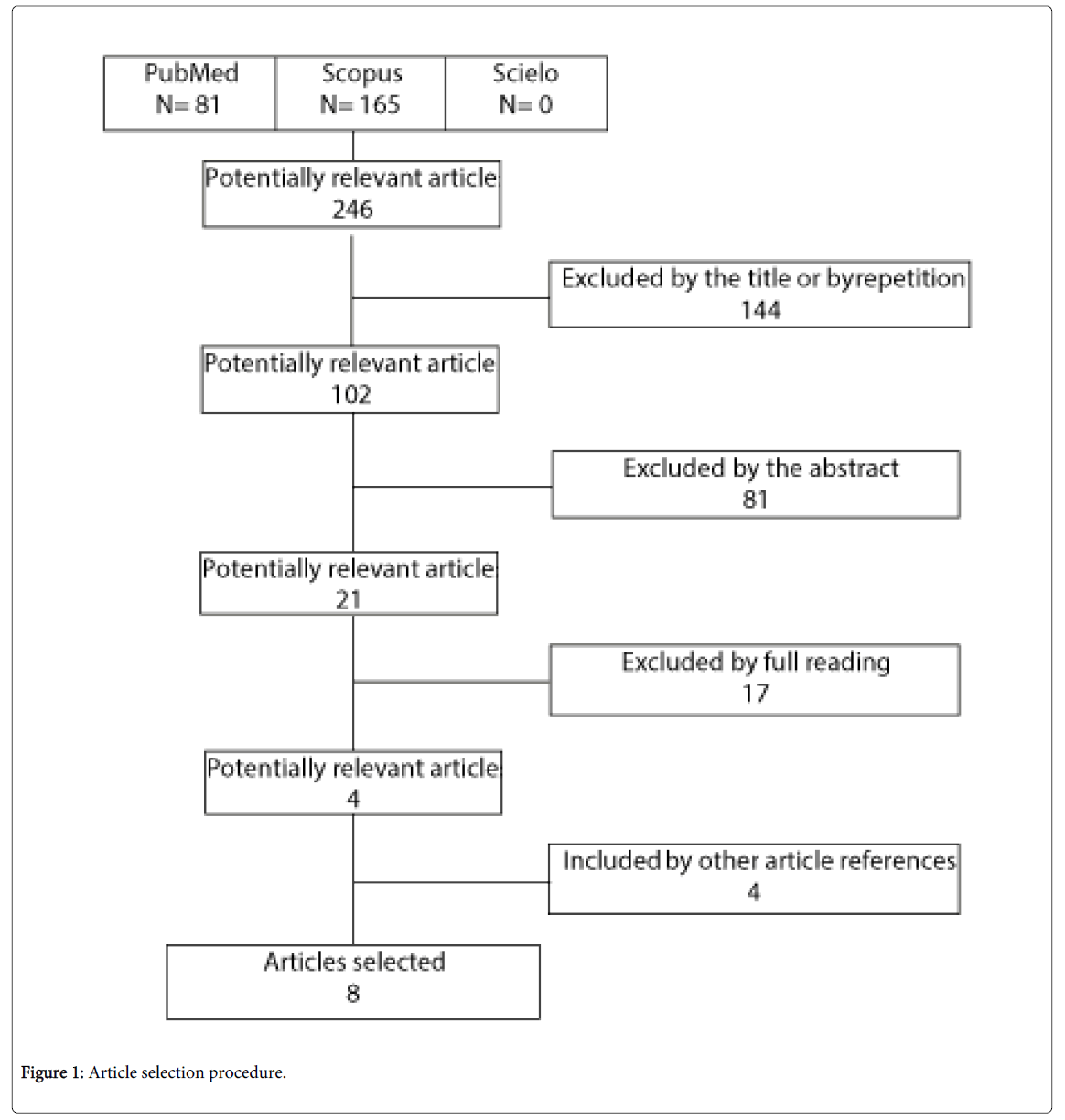

Of the 246 articles initially found, 144 were excluded after reading their titles or because they were duplicates. Secondly, after reading the abstracts of the remainder 102 articles, 81 were excluded for not seemingly answering the research question, which resulted in 21 articles (Kappa=0.70). Finally, these 21 articles were entirely read, 17 of which were excluded and four others which were meanwhile found to be relevant for this study were included (Figure 1).

Therefore, this literature review includes eight original research articles published between 2009 and 2013. Two studies took place in Sweden, three in Australia, and one in each of the following countries: U.S.A., Japan and UK. As for the quality of the studies, six articles were rated as “good" (N=6), whereas two were rated as “fair”. The total scores are described in Table 1. The target population of the studies were caregivers of patients at end of life and the general community,the latter aimed at preventive action.

| 1st author/ Year of Publication and Country |

Study type | Sample | Program name | Goals | Impact assessment? | Duration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Clarke (2010) UK |

Qualitative; Focus Group Technic. | Older people, informal caregivers, and representatives from community groups > 60 years old (N=74) |

The Listening Events (guided by the booklet Planning for Choice in End-of-Life Care) | Understand the concerns of end of life issues, providing information and encouraging reflection | Yes | Four workshops |

20 |

| 2 | Hudson, et al. (2009) Australia |

Qualitative; Questionnaire; ANOVA. |

Primary family carers of patients with advanced Cancer receiving home-based PC (N=156) |

“Carer Group Education Program” (CGEP) | Enhance the ability to develop the caregivers role | Yes | 3 sessions (each 1h30m), during three weeks | 35 |

| 3 | Collinge et al. (2013) USA |

Experimental Randomized. Flyers |

Family caregivers of cancer patients in advanced stage (N= 97) |

“Touch, Caring and Cancer: Simple Instruction for Family and Friends” (Multimedia Program - DVD) |

“Determine the impact of caregiver administered massages on patient symptoms and side effects impact of the intervention on quality of life in patients and stress levels in both patients and caregivers”. |

Yes | 4 weeks (listening 20 min session per three times per week) | 30 |

| 4 | White et al. (2008) Australia | Quantitative and qualitative; questionnaire technic; semi-structured interviews. | Family caregivers of patients living with a life-threatening illness (N=205) | “Learn Now, Live Well” (LNLW) | “Provide caregivers with practical skills in caring for someone at home; Increase awareness of existing community resources for caregivers; Increase caregivers’ confidence through knowledge and information; Promote the concepts of PC”. |

Yes | Six Modules delivered for over three Saturdays |

31 |

| 5 | Miyashita, et al. (2008) Japan |

Questionnaire, brochure. | General public focusing on end-of-life home care (N=607) |

Educational intervention | Discuss issues related to end of life decisions | Yes | One-hour educational lectures from April 2006 to March 2007 | 21 |

| 6 | Hudson, et al. (2008) Australia |

ANOVA, Questionnaire; semi-structured interviews and facilitators’ journals. | Primary caregiver of patients requiring home-based PC (N=74) |

Group Education Programme |

Evaluate the effectiveness of programs that enable the primary caregivers to take care of the patient at home | Yes | Programme was conducted via three sessions (1.5/h each) over a 3-week period |

32 |

| 7 | Witkowski et al. (2004) Sweden |

Phenomenographic method; semi-structured interviews, questionnaire. | Family members who were caring for cancer patients in advanced palliative (N=39) |

Support Group Programme of Advanced Palliative Home Care Team (APHCT) |

“To describe the opinions of participants in a support group programme about the programme and how they felt they had benefited from it”. |

Yes | A 2-year project; Each programme consisted of five sessions, and each session lasted 2 h |

27 |

| 8 | Henrlksson et al. (2007) Sweden |

Phenomenological method; Qualitative interviews. | Relatives who attend their patient during the late palliative phase in a PC unit (N=40) | Support Group Programme | “To offer relatives a chance to meet others in a similar situation, obtain information and discuss their situation with professionals”. | “An hour and a half a week for six weeks, and each meeting has a special theme with an 'expert' invited by the palliative team”. |

29 |

Table 1: Included studies: general characteristics (N=8).

Variables studied

Program theme: All educational programs described in the selected articles addressed issues related to the end of life context. Two were extended to the general public and not only to caregivers [8,9]. These actions were intended to foster discussion on general topics [8-10] increase the caregivers ability for the caregiving role and his/her well-being [3,10-12] and assess the effectiveness and level of impact of such interventions [13,14] in caregivers of patients with severe and progressive illness. A common point to all studies was the understanding that intervention groups facilitate the sharing of experiences.

Program duration and strategy: The duration of the programs referred to in the selected articles ranged from three weeks to two years. The number of sessions of each program varied between 3-6 (sessions = modules = workshops) although the study by Miyashita et al. 9 makes no reference to this aspect. All eight programs were mediated by health professionals, six of which were presented as PC experts [3,9,10,12-14].

Measurement instruments

Measurement instruments are tools that can help to assess certain factors and register their evolution. Hudson et al. [3,13] used the following measurement instruments for their studies: Carer Competence Scale [15], Preparedness for Caregiving Scale [16]; Family Inventory of Need [17], Rewards for Caregiver Scale [18], Social Support Questionnaire [19], Brief assessment scale for caregivers [15], Life Orientation Test [20]. Thus they were able to measure the caregivers’ capability, their self-awareness about their own capability, their needs, the positive aspects of life, social support, the levels of weariness and optimism.

Apart from the demographic questionnaires and satisfaction surveys applied in all studies, some authors chose to create their own instruments in order to assess the impact of the educational programs. Collinge et al. [11] created some tools for data collection which were properly translated into the English, Spanish and Chinese languages. The "weekly reporting session" developed by these researchers assessed the physical symptoms in patients during the massage therapy session given by the caregivers contemplated in the educational program. Also in this session, caregivers were asked to answer seven questions created for this study in order to measure their attitudes toward caregiving, in addition to completing the following scales: Caregiver Reaction Assessment [21], Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) [22], the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G, version 4) [23].

White et al. [10] also developed an instrument in their program to assess the caregivers’ knowledge about caregiving and the degree of reliance on care, claiming the lack of instruments that suited the purpose of the study. Miyashita et al. [9] in turn created a questionnaire which aimed to register the viability of death at the home, the barriers to home support in end of life, the therapeutic treatment preferences and caregivers’ attitudes regarding end of life care.

Location and environment

The program “The Listening Events (guided by the booklet Planning for Choice in End-of-Life Care)” was developed by an international association of assistance for the elderly called "Help the Aged" and was carried out within the community [8], as was also the case with the educational program presented by Miyashita et al. [9]. The "Learn Now, Live Well" program was developed in both a hospital and in the community and "Touch, Caring and Cancer: Simple Instruction for Family and Friends" is a multimedia program created in DVD format and therefore designed for home use.

The Support Group Programme was developed in palliative care units[12] and "Carer Group Education Program" (CGEP) makes no reference as to where the program was held, although the article states that the program was directed to relatives who were accompanied at home by PC teams [3,13].

Program assessment

All programs evaluated their respective impact using the data collection tools described above. Overall this procedure occurred in two separate steps: (1) prior to the start of the program and (2) following the end of each program. Hudson et al. [13] added a third step which was conducted during the development of the program. The study by Collinge et al. [11] was the only one to have a control group.

The “Learn Now, Live Well" program [10] showed that it was able to reduce isolation, increase the caregivers’ safety and knowledge and allow them to gain skills. As such, it is a well know and recommended program for PC teams.

The program developed by Henriksson and Andershed [12] concluded that family members of terminally ill patients benefit from aid and support groups during follow-up in PC, as these meetings allow an opportunity for caregivers to identify themselves, share experiences and have a moment of rest from caregiving. Furthermore, it provides an opportunity for caregivers to feel appreciated.

In the study by Hudson et al. [3], 56 participants stated that they felt that they were better informed and more supported/prepared and had the opportunity to share their problems. The participants also referred that they felt they were in a stronger position to speak to the medical team. The evaluation of this program indicated that it is possible to better prepare the caregiver for the caregiving role.

The study by Miyashita et al. [9] concluded that 95% of participants were satisfied with the initiative, which leads to believe that even one hour of intervention on a certain topic can change attitudes and beliefs.

Clarke [8] findings showed that before the program, participants were apprehensive to talk about the end of life issues, but at the end they showed great interest on the subject, stating that they actually have very few opportunities to discuss this issue. Furthermore, the participants acknowledged it as an important issue for the development of a community, which indicates that it might be appropriate to extend this issue/program to other professionals who deal with these issues, such as religious leaders and owners of funeral homes, among others.

The study by Collinge et al. [11] suggested that instructing caregivers about simple massages can improve the self-efficacy in managing the patient’s symptoms and increase satisfaction in providing care. It is a program that can provide safety and comfort without the need for the patient and family to travel or move. This is a program that has been approved and developed in other support centres for cancer patients in several other countries.

Finally, the study by Witkowski and Carlsson [14] introduced the idea that educational programs for caregivers have an important impact in terms of social identification. The opportunity to meet people who express common concerns effectively enhances the perception of social support in caregivers.

Limitations of the studies

The limitations described in six of the selected studies are very clear and helpful to future researchers. We now describe the key critical reflections which we believe can be useful for further research on this subject.

In the study by Hudson et al. [13] the facilitators who participated in CGEP argued that the educational program should continue, but warned that the lack of resources and the costs associated with this activity may jeopardize the continuity of a program. Hudson [3] also discussed the number of training hours that an educational program should involve and suggested that, because the relatives feel more comfortable at home, it could be wiser to create short programs. Aware of the importance to address the influence of caregivers’ well-being and mental health, the authors argued that these programs should also be tested in a hospital or palliative care units before the patients are discharged.

Henriksson and Andershed [12] pointed out to the fact that caregivers entering a program where the team members are simultaneously trainers who work in the same space where their patient is being cared for can cause the feedback of shared experiences to be forcefully positive out of fear of being perceived negatively by the professionals. White et al. [10] on the other hand, opined that the timing of the program can be a barrier to the recruitment of participants and that the stage of the patient’s illness can influence the sample size, so it is imperative to attend to the current stage of the patient’s illness.

Miyashita et al. [9] showed that the results achieved by the end of each study may have a very short effect and thus the substantiality of behavioural changes is dubious. A follow up of at least 6 months would be required for each study of this scope to assess the impact of the intervention.

Regarding the massage program developed by Collinge et al. [11] questions emerged to whether the success of the program could be influenced by the relationship developed between the participants. The authors concluded that future research on this kind of intervention should be based on a structured approach to qualitative data collection and analysis which can provide information about the quality of the patient-caregiver relationship.

Funding

Of the eight programs identified in this review, seven received funding whilst one makes no reference to funding.

Of the 43 associations contacted (representing 13 countries), six responded to the email sent in February 2013. Organizations from Austria, Belgium, Sweden, Holland, Bulgaria, and Ireland replied to the authors, stating that they had no knowledge of national formal programs designed for caregivers in PC units/teams.

Discussion

This revision verifies the lack of publications regarding programs designed and developed to support family caregivers in PC. In addition to the literature review, several European PC associations contacted interestingly reported no knowledge about formal programs currently implemented in this context. What often exists in PC units are brochures for the community (information and practical advice), training courses for volunteers, organization of lectures, presentations, meetings and conferences to inform the public about issues related to the topic of PC and government projects to improve PC. The fact that only eight programs were found between 2009 and 2013 can be indicative of the lack of funding directed towards research on this subject.

Nonetheless, it is exceptionally important to involve the patients and caregivers in PC as soon as possible in order to address their needs in such a way that makes the most of their motivations. Psychosocial interventions acknowledged and studied by several authors may be an example of good practice observed in individual and group intervention [5] but in our view are not synonymous with programs. A program requires a specific goal, outlined in a particular time frame and space, with more than one session or training modules that can meet the fluctuating needs of each caregiver [24]. Research has shown that support and education can reduce caregiver burnout [8,14] nonetheless most of this education is done through verbal or written means.

A brief search on the World Wide Web reveals some programs and formal activities aimed at supporting the caregiver, although their procedures and results have not been scientifically disclosed. The "Hospice as a Hub" is a good illustration about a PC caregiver program. This project is a new model in practice at St. Christopher’s Hospice in London that draws the hospice and the community closer together. This is a preventive and proactive program that aims to empower and enable potential caregivers in relation to patient care and self-care. Along with this project the therapeutic centre "Anniversary Centre" was created with the purpose of changing attitudes in a spontaneous and natural way. Caregivers can find information, take part in leisure activities, and enjoy food and beverages and access to the garden. Social needs can be addressed by engaging in activities such as Pilates, group sharing, art therapy, relaxation, practical courses of caregiving, group mourning (for a set period of time) and a space dedicated to spirituality (Pilgrim Room).

Milberg et al. [25] attempted to evaluate the experience of caregivers participating in this kind of program. The authors concluded that programs can often motivate feelings of insecurity, because when a caregiver decides to participate, he/she initially feels fear of not being able to identify with the other members of the group, which can cause stress. It is important that participants are informed about the program, the number and location of the sessions, the duration of the program and the topics that will be covered. Only then will there be conditions for the caregivers to be assiduous and meet their needs.

In our point of view, the creation of a formal program in a PC team should be implemented as if it were a medical appointment. This "multidisciplinary appointment" could focus on the treatment of isolation and insecurity and enhance the caregivers’ knowledge and skills as well as their self-care skills, helping to face the issues about death and dying. These programs should actively involve all the professionals of a PC team, which can thus work as elements of effective support towards caregivers.

Based on the outcome of this review, we believe that it would be interesting to develop a base of educational programs for caregivers in PC which may serve as reference for the teams that wish to undertake further work in this issue in a continued way and integrated within a team. The education and training of personal intrinsic competences influence the wellbeing of both those who promote them and those who receive them [2].

Limitations

Only 6 out of 43 European organizations of PC replied to the email sent out by the authors, therefore the present study cannot be held to be representative of the standard European PC programs directed towards caregivers. On the other hand, a search for caregiver programs on the World Wide Web could have brought further insights on the subject, as a great number of these programs are not studied in science and therefore cannot be found on scientific databases.

Conclusion

An adequate provision of PC presumes the support to caregivers as an inseparable part of patient support. Research on this subject has been done in order to increase the development of the skills of professionals in this field and improve the intervention in caregivers of patients in PC.

This study shows that there is awareness about this issue, however, it seems that the occasional interventions without specific goals can only provide caregivers with sufficient information and awareness for often general themes and possibly inadequate to the real needs of the family caregivers.

The work done so far in this subject points to an appropriate training of skills that can effectively address the caregivers specific needs, the significance of adapted and continued support, which includes the assessment of caregivers' expectations, proper information about the whole process, and the establishment of a formal program integrated within a PC team.

In this sense, we conclude that specific educational programs should be developed which promote more than caregivers’ wellbeing; rather that allow the resolution of problems with well-defined objectives that meet the individuality of caregivers.

Funding

Study sponsored by the Isabel Levy Research Fellowship of the Portuguese Association of Palliative Care.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Miguel Tavares for his remarks on this paper, and all the European organizations which kindly contributed to this study.

References

- Saunders C (1963) The treatment of intractable pain in terminal cancer. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine; 56: 194.

- Hudson PL, Trauer T, Graham S, Grande G, Ewing G, et al. (2010) A systematic review of instruments related to family caregivers of palliative care patients. Palliat Med 24: 656-668.

- Hudson P, Thomas T, Quinn K, Cockayne M, Braithwaite M (2009) Teaching family carers about home-based palliative care: final results from a group education program. J Pain Symptom Manage 38: 299-308.

- Demirbag BC (2012) Impact of home education on levels of perceived social support for caregivers of cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 13: 2453-2458.

- Tufan I, Tokgöz N, Kılıç S, Akdeniz M, Howe J, et al. (2011) Are caregiving courses useful? An empirical study from Antalya, Turkey. Arch GerontolGeriatr 52: e23-25.

- Hudson PL, Thomas K, Trauer T, Remedios C, Clarke D (2011) Psychological and social profile of family caregivers on commencement of palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 41: 522-534.

- Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, Hardey M, Powell J (2002) Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res 12: 1284-1299.

- Clarke A, Seymour J (2010) "At the foot of a very long ladder": discussing the end of life with older people and informal caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage 40: 857-869.

- Miyashita M, Sato K, Morita T, Suzuki M (2008) Effect of a population-based educational intervention focusing on end-of-life home care, life-prolonging treatment and knowledge about palliative care. Palliat Med 22: 376-382.

- White K, D Abrew N, Auret K, Graham N, Duggan G (2008) Learn Now; Live Well: an educational programme for caregivers. Int J PalliatNurs 14: 497-501.

- Collinge W, Kahn J, Walton T, Kozak L, Bauer-Wu S, et al. (2013) Touch, Caring, and Cancer: randomized controlled trial of a multimedia caregiver education program. Support Care Cancer 21: 1405-1414.

- Henriksson A, Andershed B (2007) A support group programme for relatives during the late palliative phase. Int J PalliatNurs 13: 175-183.

- Hudson P, Quinn K, Kristjanson L, Thomas T, Braithwaite M, et al. (2008) Evaluation of a psycho-educational group programme for family caregivers in home-based palliative care. Palliat Med 22: 270-280.

- Witkowski A, Carlsson ME (2004) Support group programme for relatives of terminally ill cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 12: 168-175.

- Pearlin I, Mullan T, Semple J, et al. Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist 1990; 30: 583-594.

- Archbold PG, Stewart BJ, Greenlick MR, Harvath T (1990) Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Res Nurs Health 13: 375-384.

- Kristjanson LJ, Atwood J, Degner LF (1995) Validity and reliability of the family inventory of needs (FIN): measuring the care needs of families of advanced cancer patients. J NursMeas 3: 109-126.

- Archbold G, and Stewart J (1986) Family caregiving inventory Report. Oregon Health Sciences University, School of nursing, Department of Family Nursing, Portland.

- Monteiro AP (2011) Psychometric properties of a Russian version of the Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ6) in eastern European immigrants. Contemp Nurse 39: 157-162.

- Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW (1994) Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J PersSocPsychol 67: 1063-1078.

- Given CW, Given B, Stommel M, Collins C, King S, et al. (1992) The caregiver reaction assessment (CRA) for caregivers to persons with chronic physical and mental impairments. Res Nurs Health 15: 271-283.

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R (1983) A global measure of perceived stress. J Health SocBehav 24: 385-396.

- Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, et al. (1993) The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J ClinOncol 11: 570-579.

- Brookman C, Holyoke P, Toscan J, Bender D, Tapping B (2011) Promising practices and indicators for caregiver education and suport programs, Markham: Saint Elizabeth.

- Milberg A, Olsson EC, Jakobsson M, Olsson M, Friedrichsen M (2008) Family members' perceived needs for bereavement follow-up. J Pain Symptom Manage 35: 58-69.

Relevant Topics

- Caregiver Support Programs

- End of Life Care

- End-of-Life Communication

- Ethics in Palliative

- Euthanasia

- Family Caregiver

- Geriatric Care

- Holistic Care

- Home Care

- Hospice Care

- Hospice Palliative Care

- Old Age Care

- Palliative Care

- Palliative Care and Euthanasia

- Palliative Care Drugs

- Palliative Care in Oncology

- Palliative Care Medications

- Palliative Care Nursing

- Palliative Medicare

- Palliative Neurology

- Palliative Oncology

- Palliative Psychology

- Palliative Sedation

- Palliative Surgery

- Palliative Treatment

- Pediatric Palliative Care

- Volunteer Palliative Care

Recommended Journals

- Journal of Cardiac and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Community & Public Health Nursing

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Health Care and Prevention

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Paediatric Medicine & Surgery

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Palliative Care & Medicine

- Journal of Pain & Relief

- Journal of Pediatric Neurological Disorders

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neonatal and Pediatric Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry: Open Access

- OMICS Journal of Radiology

- The Psychiatrist: Clinical and Therapeutic Journal

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 16987

- [From(publication date):

November-2014 - Apr 02, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 12197

- PDF downloads : 4790