Research Article Open Access

Down Syndrome - Onset Age of Dementia

Arvio Maria1* and Bjelogrlic-Laakso Nina M21Turku University Hospital, Oulu University, Paimio, Finland

2Tampere University Hospital, Pitkaniemi, Finland

- *Corresponding Author:

- Arvio Maria

Paijat-Hame Joint Municipal Authority

Lahti, Turku University Hospital

PEDEGO, Oulu University, Paimio

Finland

Tel: +358400835614

E-mail: Maria.Arvio@phhyky.fi

Received date: May 03, 2017; Accepted date: May 22, 2017; Published date: May 29, 2017

Citation: Arvio, Bjelogrlic-Laakso (2017) Down Syndrome - Onset Age of Dementia. J Alzheimers Dis Parkinsonism 7:329. doi:10.4172/2161-0460.1000329

Copyright: © 2017 Arvio, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Alzheimers Disease & Parkinsonism

Abstract

Background: Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of death in people who have Down syndrome. This prospective, population-based, 15-year follow-up study aimed to define the onset age of dementia. Methods: At baseline 98 adults were screened for the first time by using the Present Psychiatric State-Learning Disabilities assessment. These screenings were repeated twice more during the study. Results: The indicative signs for dementia increased rapidly after the age of 35 and appeared most frequently as reduced self-care skills, loss of energy, impaired understanding and forgetfulness. Conclusion: Regular follow-up of people who have Down syndrome from the age of 30 onward enables appropriate interventions to delay the progression of dementia.

Keywords

Down syndrome; Aging; Follow-up; Dementia

Introduction

Down syndrome (DS) is the most common genetic cause for intellectual disability. Those with DS represent 10 to 15% of all people who have intellectual disabilities [1]. DS is characterized by a delayed development in childhood, a premature aging in adulthood, and a risk of early dementia with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), which is also the most common cause of death in this population [2-4]. In spite of a well-known clinical course of DS there are currently only limited symptomatic treatments available for AD in DS [5]. The emerging evidence suggests that various environmental risk factors such as chronic inflammation present potential treatable interventions for individuals with DS at risk for AD [6,7].

According to the literature AD neuropathology is observable in virtually all individuals by the age of 40 years [8,9], after which there is generally thought to be a prodromal or asymptomatic phase when AD pathology progressively accumulates so that clinical dementia is usually recognized within an age range of 48 to 56 years [10,11]. However, the results from our recent paper with 27 years follow-up of 45 adults with DS suggested that the turning point in the course of adaptive skills occurs already at the age of 35 [12]. Our present, partly concomitant to the aforementioned study, screened clinical signs of dementia aiming to define the onset age of dementia in 98 adults during 15 years followup period.

Patients and Methods

In the late 1960’s Finland was divided into 16 state-supported regional full-service districts, providing residential care, education, rehabilitation, medical follow-up, shelter work, and day activity for individuals who have intellectual disabilities. In 2000, the client register of the South-Häme district with a total population of 340,000, included names of 229 people who have DS; from those all 115 that were older than 23 years were invited to participate this study.

During the follow-up period two special nurses visited peoples’ homes three times, in 2001, 2012 and 2016 and used the British Present Psychiatric State-Learning Disabilities assessment (PPS-LD) for screening [13,14]. This PPS-LD questionnaire (incl. 27 items) was used in this survey as it has been used in our country for the diagnosis of dementia, particularly among people who have intellectual disabilities [15,16].

The Pirkanmaa Hospital District’s ethics committee has reviewed and supported our study. We have received a written informed consent from each participant or from their caretaker.

Results

At the baseline, 98 of the 115 invited adults were willing to enroll the study. Of these, 19 had participated also in our second parallel followup survey [12]. During the 15 year follow-up period, the number of study participants decreased (Table 1). Five adults, who were alive at the end of the study refused to participate all three assessments and 52 adults died. The age at death of 27 deceased women ranged from 36 to 67 (median 57) and of 25 men from 29 to 71 as expected (median 57).

| 2001 | 2012 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (F/M) | 98 (48/50) | 62 (28/34) | 43 (19/24) |

| Age range, | 25-63 | 35-65 | 39-66 |

| Age mean, median | 42/42 | 48/52 | 49/54 |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Hypothyroidism | 25 (25%) | 29 (47%) | 18 (42%) |

| Hearth insufficiency | 12 (12%) | 7 (11%) | 3 (7%) |

| Epilepsy | 15 (15%) | 15 (27%) | 25 (58%) |

| Alzheimer disease* | 0 | 14 (23%) | 13 (30%) |

| Diabetes type 1 | 2 (2%) | 2 (3%) | 2 (5%) |

| Visual impairment | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) |

| Hypercholesterolemia**? | 7 (11%) | 5 (12%) | |

| Sleep apnea*** | 0 | 0 | 3 (7%) |

| No health problem | 32 (22%) | 6 (6%) | 3 (7%) |

*Alzheimer disease diagnosis was confirmed with brain magnetic resonance image

** Cholesterol levels were not systemically determined in 2001

*** Sleep apnea diagnosis was confirmed by polysomnography.

As expected AD was the cause of death in 47 adults. Other observed causes included paralytic ileus associated with diaphragm hernia in a man (deceased at the age of 29), congenital heart defect in a woman (deceased at the age of 36), cortical multi-infarctation related to moyamoya disease in a woman (deceased at the age of 45); pancreatic cancer in a women (deceased at the age of 56) and laryngeal cancer in a man (deceased at the age of 57).

At the baseline 78% and at the end of the study 93% of the adults had one (or more) longstanding health problem(s) (Table 1).

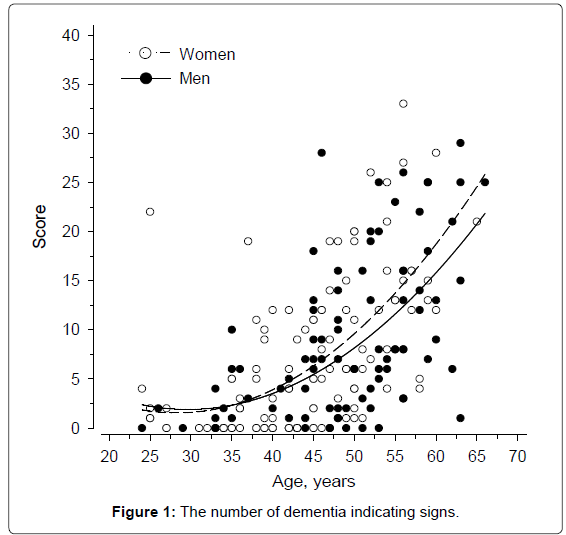

The dementia signs increased rapidly after the age of 35 (Figure 1). Of the 98 participants, 43 underwent all three assessments. The division and number of their dementia signs at baseline and at the end of the study are presented in Table 2. The most commonly occurring symptoms were reduced self-care skills, loss of energy, impaired understanding, and forgetfulness. Local physicians had prescribed acetylcholinesterase inhibitor or memantine to 16 out of 27 adults who had been diagnosed with AD; according to the sparse available documentation the medication was discontinued in three adults because of poor response.

| 2001 | 2012 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sign | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) |

| Autonomic anxiety | 1 (2) | 9 (21) | 10 (23) |

| Change in appetite | 1 (2) | 3 (7) | 5 (12) |

| Changed sleep pattern | 2 (4) | 13(30) | 14 (33) |

| Coarsening of personality | 0 | 9 (21) | 10 (23) |

| Confusion | 1 (2) | 5 (12) | 5 (21) |

| Delusions | 1 (2) | 3 (7) | 4 (11) |

| Diurnal mood variation | 2(4) | 5 (12) | 9 (21) |

| Forgetfulness | 2 (4) | 18 (42) | 18 (42) |

| Forgetting people�?´s names | 1 (2) | 3 (7) | 3 (7) |

| Geographical disorientation | 1 (2) | 6 (14) | 6 (14) |

| Impaired understanding | 11 (25) | 15 (35) | 22 (51) |

| Irritability | 4 (11) | 11 (25) | 12 (28) |

| Loss of concentration | 3 (7) | 13 (30) | 14 (33) |

| Loss of energy | 12 (28) | 26 (65) | 24 (56) |

| Loss of literacy skills | 1 (2) | 4(11) | 4 (11) |

| Misery | 4 (11) | 6 (14) | 6 (14) |

| Onset of or increase in | |||

| -maladaptive behavior | 3 (7) | 3 (7) | 7 (16) |

| -physical aggression | 3 (7) | 4 (11) | 7 (16) |

| - verbal aggression | 3 (7) | 4 (11) | 4 (11) |

| - fearfulness | 3 (7) | 10 (23) | 10 (23) |

| Reduced | |||

| -quantity of speech | 7 (16) | 16(37) | 17 (40) |

| -self-care skills | 10 (23) | 23 (53) | 25 (58) |

| -social interaction | 1 (2) | 8 (19) | 8 (19) |

| Tearfulness | 1 (2) | 4 (11) | 8 (19) |

| Temporal disorientation | 3 (7) | 9 (20) | 10 (23) |

| Weight change | 7 (16) | 7 (16) | 16 (37) |

| Worry | 3 (7) | 9 (21) | 10 (23) |

Table 2: The division of dementia signs in 43 people with all three evaluations.

Discussion and Conclusion

Our recent study suggests that the adaptive skills in people with DS start to deteriorate at the age of 35 [12] and the current findings indicate that also the first signs of dementia appear at the same age. These long-term longitudinal observations do dispute the prevailing understanding that neuropathology [8,9] occurring concomitantly with a prodromal or asymptomatic phase precedes clinical dementia [4,10,11]. It can be speculated here whether the lack of this kind of long-term clinical data and/or the varying clinical follow-up methods utilized in different countries could explain this evident discrepancy between our results and the findings published by the others.

In spite of a well-known association between AD and DS there are no clinical guidelines for the health management of this specific disorder. Firstly, the role of pharmacotherapy is unclear [17]. Secondly, there are practical hindrances for the use of AD medication. For example, here in Finland brain imaging is required for the reimbursement of AD medication even though clinical diagnosis of dementia in people who have DS has been considered valid and reliable [18]. This results in an inevitable problem. Because of non-compliance the imaging cannot usually be done without a general anesthetic and, thus, it is often not done. Consequently, only a small portion of those who have DS and AD may literally end up taking an appropriate AD medication. For example in this study only 60% of the those with diagnosed AD were on appropriate medication and only 13 out of 16 patients had continued the prescribed medicine. On the other hand, AD is known to be the leading cause of death in DS [3,4] as confirmed also by this survey. All this indicates the urgent need for further studies to find out what the most cost-effective treatment options would be.

Currently, most of the Finnish adults who have intellectual disabilities live in subsidized housing units and they have (unlike general population) usually undergone several psychological tests during their adolescent years making it rather easy to recognize any change there may occur later on in their cognition. We have found PPS-LD form used in this and other studies (related to fragile X and Williams syndromes) useful and simple for identification of early signs of dementia when this evaluation form is completed at regular intervals by a carer, who has known the person for a long time. Perhaps, this kind of long-term care by the same nurse explains why the first dementia signs were recognized at clearly younger age in our study than in the surveys conducted by the others (i.e. 35 versus 48-56 years) [4-7].

Early recognition of dementia can be claimed to be of uttermost importance, because any deterioration in daily performance due to some treatable but undiagnosed condition may result in institutionalization. Once some ailment in memory has been observed, it does not necessarily reflect the onset of AD. For example, depression, sleep disorders, B12-vitamin deficiency, hypothyroidism, urinary tract infections or polypharmacy may be the underlying causes behind the first dementia signs. Even an aggressive form of periodontitis has been suggested as one modifiable risk factor for AD in DS population [6]. In other words, without regular follow-up records the initiation of appropriate medical examinations and consequent interventions [19] may be delayed with undesired long-term consequences. On the other hand, the recent advances in understanding the molecular basis of ID and pathogenesis of AD can be expected to yield new therapeutic interventions [5]. All this together with our results and clinical experience emphasize the importance of active health management of people with DS in order to improve their general wellbeing and to extend their period of living at home.

References

- Strømme P (2000) Aetiology in severe and mild mental retardation: A population-based study of Norwegian children. Dev Med Child Neurol 42: 76-86.

- Tsao R, Kindelberger C (2009) Variability of cognitive development in children with Down syndrome: Relevance of good reasons for using the cluster procedure. Res Dev Disabil 30: 426-432.

- Tyrrell J, Cosgrave M, McCarron M, McPherson J, Calvert J, et al. (2001) Dementia in people with Down's syndrome. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 16: 1168-1174.

- Head E, Powell D, Gold BT, Schmitt FA (2012) Alzheimer's disease in Down syndrome. Eur J Neurodegener Dis 1: 353-364.

- Rafii MS (2016) Improving memory and cognition in individuals with Down syndrome. CNS Drugs 30: 567-573.

- Kamer AR, Fortea JO, Videla S, Mayoral A, Janal M, et al. (2016) Periodontal disease's contribution to Alzheimer’s disease progression in down syndrome. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2: 49-57.

- Wilcock DM, Griffin WS (2013) Down's syndrome, neuroinflammation and Alzheimer neuropathogenesis. J Neuroinflammation 10: 84.

- Prasher V, Cumella S, Natarajan K, Rolfe E, Shah S, et al. (2003) Magnetic resonance imaging, Down’s syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease: Research ja clinical implications. J Intellect Disabil Res 47: 90-100.

- Beacher F, Daly E, Simmons A, Prasher V, Morris R, et al. (2010) Brain anatomy and ageing in non-demented adults with Down's syndrome: An in vivo MRI study. Psychol Med 40: 611-619.

- Devenny DA, Krinsky-McHale SJ, Sersen G, Silverman WP (2000) Sequence of cognitive decline in dementia in adults with Down's syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res 44: 654-665.

- Ghezzo A, Salvioli S, Solimando MC, Palmieri A, Chiostergi C, et al. (2014) Age-related changes of adaptive and neuropsychological features in persons with down syndrome. PLoS ONE 9: e113111.

- Arvio M, Luostarinen L (2016) Down syndrome in adults: A 27 year follow up of adaptive skills. Clin Genet 90: 456-460.

- Cooper SA (1997) Psychiatric symptoms of dementia among elderly people with learning disabilities. Int J Geriatr Psychiatr 12: 622-666.

- Cooper SA (1997) A population-based health survey of maladaptive behaviours associated with dementia in elderly people with learning disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res 41: 481-487.

- Arvio M, Ajasto M, Koskinen J, Louhiala L (2013) Middle-aged people with Down syndrome receives good care in home towns (In Finnish). Finnish Medical Journal 15: 1108-1112.

- Molsa P (2001) Dementia and intellectual disability (in Finnish). Finnish Medical Journal 13: 1495-1497.

- Livingstone N, Hanratty J, McShane R, Macdonald G (2015) Pharmacological interventions for cognitive decline in people with down syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 29: CD011546.

- Sheehan R, Sinai A, Bass N, Blatchford P, Bohnen I, et al. (2015) Dementia diagnostic criteria in down syndrome. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 30: 857-863.

- Cooper SA, Caslake M, Evans J, Hassiotis A, Jahoda A, et al. (2014) Toward onset prevention of cognitive decline in adults with Down syndrome (the TOP-COG study): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 15: 202.

Relevant Topics

- Advanced Parkinson Treatment

- Advances in Alzheimers Therapy

- Alzheimers Medicine

- Alzheimers Products & Market Analysis

- Alzheimers Symptoms

- Degenerative Disorders

- Diagnostic Alzheimer

- Parkinson

- Parkinsonism Diagnosis

- Parkinsonism Gene Therapy

- Parkinsonism Stages and Treatment

- Stem cell Treatment Parkinson

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 3703

- [From(publication date):

June-2017 - Apr 03, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 2883

- PDF downloads : 820