Short Communication Open Access

Dont Forget the Skin: 4 Common Dermatologic Manifestations of Internal Malignancy

Reid A Waldman and Steven D Waldman*University of Missouri School of Medicine, Missouri, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Steven D Waldman, MD, JD, MBA

Clinical Professor of Anesthesiology

University of Missouri School of Medicine, Missouri, USA

Tel: 913-327-5999

E-mail: sdwaldmanmd@gmail.com

Received date September 16, 2015; Accepted date October 03, 2015; Published date October 06, 2015

Citation: Waldman RA, Waldman SD (2015) Don’t Forget the Skin: 4 Common Dermatologic Manifestations of Internal Malignancy. J Oncol Med & Pract 1:102.doi:10.4172/jomp.1000102

Copyright: © 2015 Waldman RA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at

Abstract

The skin is a unique marker for malignancy as these cutaneous manifestation not only often precede the development of other symptoms, but also often cause patients to seek medical attention sooner than they would for other symptoms. Common cutaneous markers for malignancy include: acanthosis nigricans, carcinoid syndrome, Leser-Trelat sign, and necrolytic migratory erythema. Although these skin signs can also be associated with benign disease, the clinician should have a low threshold for carefully evaluating patients with a cutaneous complaint for underlying systemic disease, as these signs are often harbingers of underlying malignancy.

Keywords

Acanthosis; Carcinoid syndrome; Necrolytic migratory erythema; Malignancy

Introduction

The skin is a unique marker for malignancy as these cutaneous manifestations not only often precede the development of other symptoms, but also often cause patients to seek medical attention sooner than they would for other symptoms. With that in mind, it is of utmost importance that physicians recognize dermatologic conditions associated with internal malignancy as identifying these diseases can lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment of these underlying disease states. In fact, even lesions that are usually benign can serve as a sign of underlying disease in certain instances. This article will provide a brief overview of four common dermatologic signs of internal disease ranging from acanthosis nigricans to necrolytic migratory erythema.

Acanthosis Nigricans

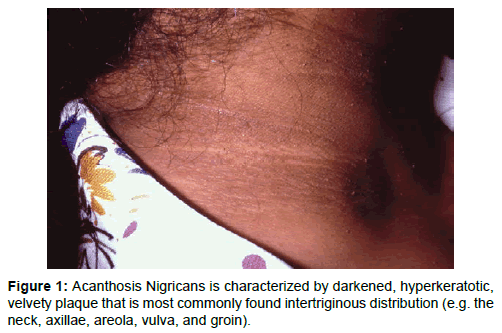

Acanthosis Nigricans (AN) is an increasingly common skin condition which is present in roughly 74% of the obese population [1]. It is characterized by darkened, hyperkeratotic, velvety plaque that is most commonly found intertriginous distribution (e.g. the neck, axillae, areola, vulva, and groin) (Figure 1). It is present in from elementary school age to the elderly and is seen most often in Blacks, Hispanics, and Native Americans [2]. In addition to its cosmetic implications some patients find their plaques to be painful or malodourous. The diagnosis of AN is almost always possible on clinical grounds, but biopsy of atypical lesions will help clarify the diagnosis. The typical biopsy of AN will reveal hyperkeratosis, infiltration with leukocytes, epidermal folding, and melanocyte proliferation.

There are a variety of underlying causes of acanthosis nigricans. While most cases are due to underlying hyperinsulinemia, it is very important to assess these patients for underlying malignancy, nicotinic acid use, or hypothyroidism. Malignancy should be especially high on the differential in patients who are euglycemic, who have rapid development of disease, who have involvement of the mucous membranes, or who have especially diffuse disease. Other clues that a patient suffering from acathosis nigricans may be suffering from an underlying malignancy is the finding of associated skin tags, the sudden onset of multiple seborrheic keratosis or tripe palms, which is a dermatologic syndrome characterized by velvety, ridge-like lesions of the palms (Leser-Trelat sign). It is worth noting that worsening of AN in obese patients with pre-existing AN has been associated with underlying malignancy. The most commonly associated with adenocarcinomas especially those that are gastric (responsible for 60% of malignancy associated cases), colonic, hepatic, and ovarian [3].

In addition to addressing the underlying illness, there are a variety of treatment modalities that can be used including topicals, oral medications, laser therapy, and surgery. A topically applied combination of tretinoin .1% and ammonium lactate 12% is especially effective at lightening these plaques [4]. This treatment option is not recommended in cases of vulvar or areolar AN as medication induced irritation is common. Topical Calcitriol has also been shown to be effective in slowing the proliferation of keratinocytes therefore lightening the lesions [5]. In those who fail topical therapy oral isotretinoin can be attempted. This should be avoided in patients with hepatic involvement due to the risk of worsening hepatic disease as a result of the drug. Finally, patients can also try laser therapy, dermabrasion, and surgery to alleviate the disease.

Carcinoid Syndrome

Carcinoid tumors, a gut neuroendocrine tumor (NET), are the most common type of neuroendocrine tumor. They most commonly occur in the ileum and the appendix and often have metastasized to the liver by the time of diagnosis. The average age of diagnosis is approximately age 60; however, it often occurs earlier in those with Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia 1 (MEN1) and cases have been documented in children [6].

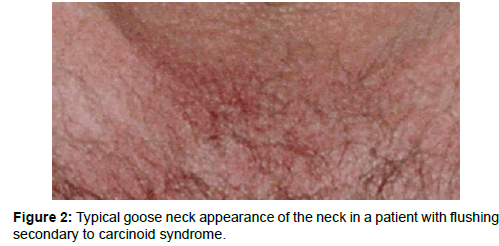

While the majority (80%) of tumors is asymptomatic, some are associated with classic carcinoid syndrome [7]. Carcinoid syndrome is characterized by flushing of the face and back of the neck (so called “Goose Neck”), diarrhea, bronchospasm, and right-sided valvular disease (e.g. pulmonic and tricuspid stenosis) (Figure 2) This occurs when carcinoid tumors secrete serotonin, tachykinins, and vasoactive peptides. Usually, carcinoid syndrome only occurs after metastasis to the liver has occurred as the liver is capable of degrading the aforementioned secretory products.

Three specific dermatologic afflictions have been associated with carcinoid tumors. Most commonly, transient flushing of the face lasting approximately 15-30 minutes occurs [8]. In rare cases, this flushing can progress to permanent changes which appear nearly identical to rosacea. Less commonly, a pellagra-like eruption can occur (e.g. erythema, hyperkeratosis, scaling, and xerosis). This usually occurs in patients who have already experienced flushing. This development likely happens as a result of tumor-mediated niacin deficiency secondary to the use of tryptophan for serotonin production. Finally, rarely, in very advanced cases, scleroderma can develop.

Leser-Trelat Sign

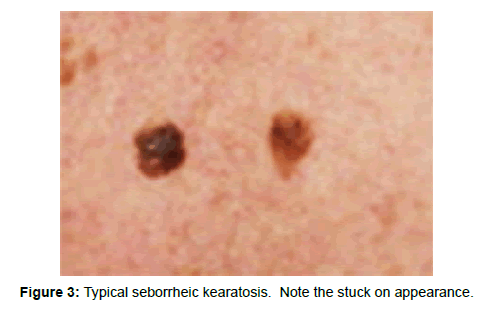

Leser-Trelat Sign is characterized by the abrupt development of large numbers of seborrheic keratosis (SK) secondary to underlying malignancy. Seborrheic Keratosis is sharply demarcated hyperkeratotic, popular lesions that are “stuck on” in appearance (Figure 3). In addition to the startling appearance of these lesions many patients complain that they itch. They most often occur on the back and chest; however, they have the propensity to occur anywhere. There is controversy over the legitimacy of Leser-Trelat sign as many patients will develop diffuse seborrheic keratosis as they age. The significance of the development of large numbers of SKs is entirely dependent on the extremely rapid onset of these extensive lesions [9].

The association between the development of seborrheic keratosis and malignancy is believed to be due to the production of transforming growth factor-alpha and epidermal growth factors by internal tumors. In fact, studies have shown that SKs secondary to malignancy stain significantly more for the presence of epidermal growth factor receptors [10]. It is worth knowing that biopsy of these lesions will not differentiate lesions associated with malignancy from SKs that are the result of benign process as the actual seborrheic keratosis itself is a benign lesion. When it is associated with malignancy, the SK itself should be thought of as an obligate paraneoplastic syndrome in a manner analogous to acanthosis nigricans. While Leser-Trelat Sign is classically associated with GI malignancies (gastric, colorectal, carcinoid, etc.) with colorectal carcinoma making up 11% of the reported cases, it has also been linked to a wide variety of other cancers including AML, prostatic adenocarcinoma, malignant melanoma, hepatic adenocarcinoma, lung cancer, and breast cancer [11].

Necrolytic Migratory Erythema and Glucagonoma Syndrome

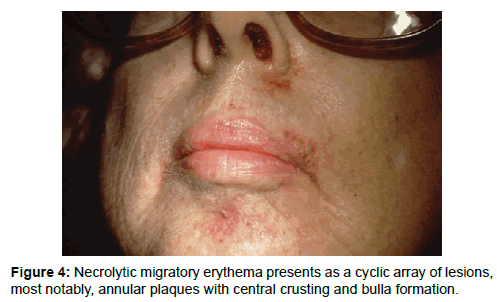

Classically, glucagonoma Syndrome is characterized by the presence of necrolytic migratory erythema, diabetes mellitus, diarrhea, weight loss, stomatitis, and cheilitis secondary to an underlying glucagonoma. A glucagonoma is an alpha-cell islet tumor of the pancreas. NME is a rash that most commonly occurs in the setting of glucagonoma Syndrome. It is frequently misdiagnosed as a variety of inflammatory dermatoses (e.g. psoriasis, bullous pemphigoid, etc.) resulting in significant delay in the diagnosis of the underlying glucagonoma. As a result, approximately have of all glucagonomas have metastasized by the time of diagnosis [12]. Additionally, it is worth noting that NME is rarely the only symptom present in patients with glucagonoma.

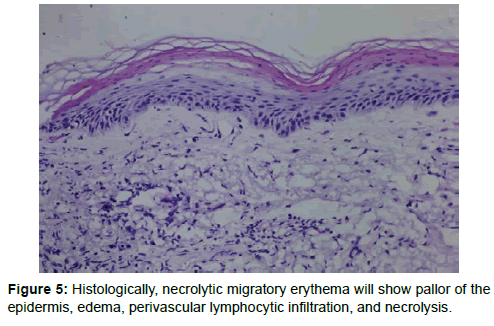

NME presents as a cyclic array of lesions, most notably, annular plaques with central crusting and bulla formation (Figure 4). These lesions are often diffuse and because of their tendency to spread centrifugally confluence often occurs. Typically, the central portion of these lesions resolves within 14 days leaving behind hyperpigmented skin. It is very difficult to distinguish this lesion from other inflammatory dermatoses on gross appearance alone. Biopsy can help with diagnosis especially if the periphery of an early lesion is taken. Histologically this will show pallor of the epidermis, edema, perivascular lymphocytic infiltration, and necrolysis [13] (Figure 5). Unfortunately, these lesions are often histologically indistinguishable from subacute dermatitis. NME should be high on the differential of patients with many of the other stigmata of glucagonoma syndrome especially those with lesions that fail to respond to high-potency corticosteroid therapy and those with cyclic lesions occurring at a greater frequency. Finally, it is worth noting that NME has been reported in patients with cirrhosis, other pancreatic tumors, non-tropical sprue, and chronic pancreatitis.

Conclusion

While this article specifically focuses on four common cutaneous manifestations of internal malignancy, it is meant to serve as a reminder that the skin can often be the home to initial signs of fatal disease. As a result, it is of paramount importance for the clinician to not trivialize dermatologic complaints as delay in diagnosis can have grave consequences. Additionally, as evidenced by acanthosis nigricans and Leser-Trelat Sign, lesions that are often benign can be the harbinger of malignancy, especially in cases where these lesions behave differently than expected. Ultimately, practitioners should have a low threshold for examining patients with a cutaneous complaint for underlying disease.

References

- Kapoor S (2010) Diagnosis and treatment of Acanthosisnigricans. Skinmed 8: 161-164.

- Guran T, Turan S, Akcay T, Bereket A (2008) Significance of acanthosisnigricans in childhood obesity. J Paediatr Child Health 44: 338-341.

- Braverman IM (2002) Skin manifestations of internal malignancy. ClinGeriatr Med 18: 1-19, v.

- Kapoor S (2010) Diagnosis and treatment of Acanthosisnigricans. Skinmed 8: 161-164.

- Hae-Woong Lee, Sung-Eun Chang, Mi-Woo Lee, Jee-Ho Choi, Kee-Chan Moon, et al. (2005) Hyperkeratosis of the nipple associated with acanthosisnigricans: with topical calcipotriol. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 52: 529-530.

- Channa N, Jayasena, Waljit S Dhillo (2013) Carcinoid syndrome and neuroendocrine tumours. Medicine 41: 566-569.

- AleciaVandevelde, Parshotam Gera (2015) Carcinoid tumours of the appendix in children having appendicectomies at Princess Margaret Hospital since 1995. Journal of Pediatric Surgery.

- Christine E Kleyn, Hazel Bell, Graham Postin, Niall Wilson (2004) Cutaneous manifestations of the malignant carcinoid syndrome1. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 50: P113.

- Constantinou C, Dancea H, Meade P (2010) The sign of Leser-Trelat in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Am Surg 76: 340-341.

- Ceylan C, Alper S, Kilinç I (2002) Leser-Trelat sign. Int J Dermatol 41: 687-688.

- Constantinou C, Dancea H, Meade P (2010) The sign of Leser-Trelat in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Am Surg 76: 340-341.

- Lobo I, Carvalho A, Amaral C, Machado S, Carvalho R (2010) Glucagonoma syndrome and necrolytic migratory erythema. Int J Dermatol 49: 24-29.

- Kovács RK, Korom I, Dobozy A, Farkas G, Ormos J, et al. (2006) Necrolytic migratory erythema. J CutanPathol 33: 242-245.

Relevant Topics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 13622

- [From(publication date):

November-2015 - Nov 30, 2024] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 9351

- PDF downloads : 4271