Does The Timetable Of Public Assistance Payments Affect Visits At The Psychiatric Emergency Room?

DOI: 10.4172/1522-4821.1000489

Abstract

Introduction: Many psychiatric patients in urban areas of the US receive Supplemental Security Income (SSI). It is conceivable that depletion of funds triggers for some patients a visit to emergency room (ER). If this was the case, it could be expected to register an increase numbers of visits of SSI recipients towards the end of the payment cycle. If this is not the case, the suspicion that admission to the hospital might also provide a secondary gain, should be remove as a consideration, so that patients can receive an unbiased assessment. Methods: Charts of patient’s visits at the psychiatric ER of Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia were reviewed. The relationship between the number of days after receiving the benefits payment and time of presentation to the ER was analyzed. Homelessness status and the presence of a positive drug test were also considered. Results: 274/1007 of patients who visited the ER visits during 2018 were recipients of SSI. No relationship was found between visit time and days elapsed since last benefits check. The interval between receiving benefits and visiting the ER had no relationship to homelessness status (p=0.9271) or the presence of a positive drug screen (p=0.0752) Conclusion: There was no increase in ER visits at the end of the payment cycle to suggest that exhausted funds played a role, either as a psychosocial stressor or as a motivation for the secondary gain. Despite the limitations of this study, denying admission to a patient based on suspicions of secondary gains should be reconsider

Introduction

Residents of major US metropolitan areas suffering from severe mental illnesses, are often poor and homeless, and have to rely on supplemental security income (SSI) which does not always cover all their basic expenses. As of December 2019, there are 3,497,980 US citizens receiving SSI for mental illnesses of which 720,464 were diagnosed with mood disorder and 406,900 with psychotic disorder. It has been speculated that occasionally when individuals are out of funds, the main driver for emergency room (ER) visits is to obtaining shelter and food. More specifically it can be speculated that towards the end of the SSI allowance cycle, patients are more likely to run out of funds and approach the ER seeking relief from stress and hospitalization. Because patient complain(s) is the main component of the psychiatric diagnosis, and confirmatory laboratory or imaging tests are rarely helpful, a certain degree of diagnostic uncertainty always exists. Occasionally, this uncertainty is the basis for denying a patient hospital admission.

To investigate potential relationships between timing of potential benefits depletion and psychiatric ER visits, data accumulated over 12 months at a general hospital serving a low-income metropolitan area was reviewed.

Methods

Data generated from Electronic Medical Records on all patients who presented at the psychiatric ER at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia between 1/1/2018 and 12/31/2018 was reviewed. Of 1007/381(37%) patients reported that they are on SSI. Of the 382 patients 10 were excluded for incomplete data, and 98 were excluded because they receive additional income such as retirement pension or VA pension, Also, a number of individuals are receiving the SSI checks through a third party hence, they have no control of their funds, leaving 274 patients for the primary analysis. For secondary analysis the patients were divided into homeless (n=107) and non-homeless, and patients who tested positive on a urine drug screen (UDS) (n=152) and these who did not.

The SSI website calendar indicating which day of the month payments were sent was used to calculate for each patient’s visit how many days elapsed between the last check received and the ER visit. For each of the groups mean, median and coefficient of Kurtosis was calculated. The Mann-Whitney test was used to check difference between the main group and the two subgroups (with 95% confidence).

Results

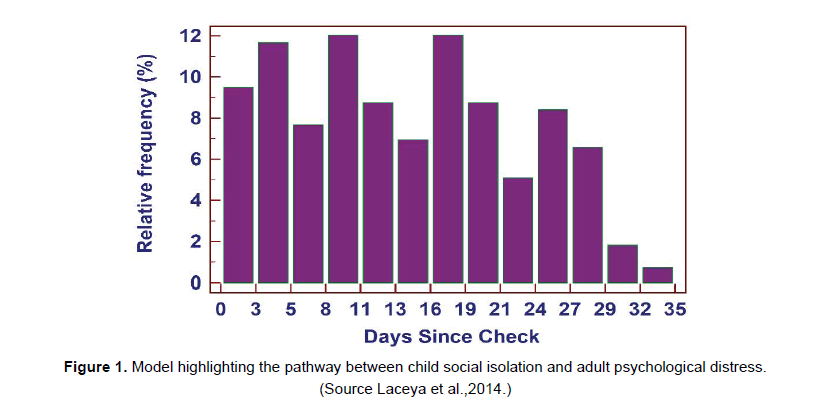

For patients on SSI, a mean of 13.9 and a median of 14 days between the last SSI check and presentation to the ER were found suggesting a uniform random distribution. The D’Agostino-Pearson test for Normal distribution rejected normality (P<0.0001) and the coefficient of kurtosis was -1.0631 (P<0.0001) with a platykurtic distribution (Figure 1). Platykurtic distribution has fewer values in the tails and fewer values close to the mean, which means, in this case that the values are more likely to be evenly distributed over the span of the month.

For the group of patients on SSI who are also homeless, we found a mean of 13.98 and a median of 11 days between the last SSI check and presentation to the ER. The D’Agostino- Pearson test for Normal distribution rejected normality (P<0.0001) and the coefficient of kurtosis was -1.0033 (P<0.0001) with a platykurtic distribution.

For the group of patients on SSI who tested positive on a urine drug screen in the ER, we found a mean of 13.1 and a median of 11.5 days between the last SSI check and presentation to the ER. The D’Agostino-Pearson test for Normal distribution rejected normality (P<0.0001) and the coefficient of kurtosis was -0.8677 (P<0.0002) with a platykurtic distribution.

The Mann Whitney test did not show any statistically significant difference between the distribution of patients on SSI who are homeless and patients who are on SSI who are not homeless (Z=-0.0915, P=0.9271).

The Mann Whitney test did not show any statistically significant difference between the distribution of patients on SSI who are tested positive on a UDS and patients who did not test positive on a UDS (Z=-1.779, P=0.0752).

Discussion

Several studies have investigated whether there is an “end of the month” pattern to presentations of other chronic illnesses for patients receiving benefits through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the results are mixed. While one study suggests a link between the timing of SNAP benefits and ER visits for pregnant women (Arteaga et al., 2015), no such relationship was demonstrated for children with asthma (Heflin et al., 2019). One study found an increased risk of hypoglycemia for low-income patients at the end of the benefit cycle (Basu et al., 2017), while another that examined Medicaid claims in Missouri found no relationship between SNAP benefits and ER visits for hypoglycemia (Heflin et al., 2017). With regards to the behavioral consequences of depletion of benefits, a study looking at Chicago Public Schools found that while disciplinary infractions increased at the end of the month for all students, that spike was more pronounced in students receiving SNAP (Gennetian et al., 2016).

If indeed the hypothesis of increased visits to the ER by the end of the payment cycle and depletion of funds is supported by data, this has social and health care delivery implication since using psychiatric hospital beds to provide food and shelter would constitute a misuse of already strained resources. On the other hand, lack of such data should call for caution and reconsideration when a patient is denied admission based on suspicion of secondary gains.

Data presented here does not support the hypothesis that psychiatric ER visits by recipients of SSI are more frequent towards the end of the payment cycle. Indirectly the data does not support the notion that towards the end of the SSI payment cycle patients are more likely to visit the ER in order to obtained food and shelter.

The data has a number of limitations. First, the findings are not based on a comprehensive, structured assessment of the patients hence, social, demographic or illness related variables might interact with the cycle of payments and affect the time and the frequency of ER visits. Second, SSI status was self-reported by the patients and may create some bias. Third, despite our attempt to consider all sources of pension income it could be those other types of formal or informal income might have affected the findings.

While community care for patients suffering from severe mental illnesses in metropolitan areas remains an acute problem, it appears that hospital psychiatric beds are not misused as an alternative to hostels or other types of accommodations.

Patients presenting to psychiatric ER with vague, inconsistent or atypical symptoms should be considered as such rather than be suspected of secondary gains and summarily discharged.

References

- Arteaga I, Heflin C, Hodges L (2018). SNAli Benefits and liregnancy-Related Emergency Room Visits. lioliul Res liolicy Rev; 37(6): 1031–1052.

- Heflin C, Hodges L, Mueser li (2017). Sulililemental Nutrition Assistance lirogam benefits and emergency room visits for hylioglycaemia. liublic Health Nutr. 20(7): 1314–1321.

- Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Seligman H (2017). The Monthly Cycle of Hylioglycemia. Med Care; 55(7): 639–645.

- Heflin C, Arteaga I, Hodges L, Ndashiyme JF, Rabbitt Mli (2019). SNAli benefits and childhood asthma. Soc Sci Med. 220: 203–211.

- Gennetian LA, Seshadri R, Hess ND, Winn AN, Goerge RM (2016). Sulililemental nutrition assistance lirogram (SNAli) benefit cycles and student discililinary infractions. Soc Serv Rev. 90(3): 403–433.

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 1857

- [From(publication date): 0-2021 - Mar 31, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1219

- PDF downloads: 638