Research Article Open Access

Does Glycated Haemoglobin Reflect Blood Glucose Levels in Women with Gestational Diabetes?

Vincent W Wong*

Liverpool Diabetes Collaborative Research Unit, Ingham Institute of Applied Medical Science, South Western Sydney Clinical School, University of New South Wales, Australia

- *Corresponding Author:

- Vincent W Wong

Liverpool Diabetes Collaborative Research Unit

Ingham Institute of Applied Medical Science

South Western Sydney Clinical School

University of New South Wales, Australia

Tel: 61287384577

E-mail: Vincent.wong@sswahs.nsw.gov.au

Received date: May 05, 2017; Accepted date: May 16, 2017; Published date: May 21, 2017

Citation: Wong VW (2017) Does Glycated Haemoglobin Reflect Blood Glucose Levels in Women with Gestational Diabetes? J Preg Child Health 4:322. doi:10.4172/2376-127X.1000322

Copyright: © 2017 Wong VW. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Pregnancy and Child Health

Abstract

Background: The value of performing glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) at a late stage of pregnancy to assess glycaemic status for women with gestational diabetes (GDM) is unclear, and the correlation between HbA1c and blood glucose level (BGL) in women with GDM is unknown. This study examined the association between 36 week HbA1c and BGL readings from daily blood glucose monitoring over the previous 28 day period. Methods: HbA1c was measured in 120 consecutive women with GDM at 36 week’s gestation and their glycaemic profiles from self-monitoring of BGL in the previous 4 weeks were documented. Results: HbA1c performed at 36 weeks was found to have weak correlation with capillary BGLs: with mean fasting BGL (R2=0.0624, p=0.006) and with mean post-prandial BGL (R2=0.1117, p=0.001) in the prior 28 days. When the 36 week HbA1c was divided into quartiles, women in the higher HbA1c quartiles had greater proportion of their BGLs above 2 sets of treatment targets (target 1: fasting BGL<5.5, 2 h post-prandial BGL<7.0 mmol/L; and target 2: fasting BGL<5.3 mmol/L and 2 h post-prandial BGL<6.7 mmol/L). For women on diet control, the percentage of women with >20% of their BGLs that exceeded treatment targets (which would indicate need for insulin therapy at our institution) increased across HbA1c quartiles in a stepwise fashion. Conclusion: HbA1c will not replace BGL monitoring in women with GDM, but may be a useful supportive tool to assess glycaemic status, especially in women who perform limited BGL monitoring.

Keywords

Gestational diabetes mellitus; Glycated haemoglobin; Glycaemic profile; Compliance; Glucose monitoring

Introduction

In women with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus, elevated glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in early pregnancy is a predictor for adverse pregnancy outcomes [1,2]. However, the value of measuring HbA1c at a later stage of pregnancy in women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is controversial. A recent study had demonstrated that HbA1c, either at the time of diagnosis of GDM or towards the end of pregnancy, were both associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes [3]. There is little utility of diagnosing GDM using HbA1c, as there is a considerable overlap between GDM and women with normal glucose tolerance [4]. Self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) is the recommended tool for assessing glycaemic status in a woman with GDM. Although the American Diabetes Association and the Australian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society have not recommended measuring HbA1c as part of management of GDM [5,6], some clinicians still routinely perform HbA1c in women with GDM, in addition to SMBG.

The aim of this study is to assess whether HbA1c adequately reflects the glycaemic profile of women with GDM.

Materials and Methods

At this institution, all pregnant women undergo 75 g oral glucose tolerance test at 26-28 week’s gestation. GDM is diagnosed when fasting glucose ≥ 5.5 mmol/L or if the 2 h glucose ≥ 8.0 mml/L. HbA1c was routinely measured at 36 week’s gestation for women with GDM. Women with GDM were asked to perform SMBG using a blood glucose meter (Freestyle Freedom Lite, Alameda, CA, USA). At this institution, the fasting glucose target was set at 3.5-5.4 mmol/L while the 2 h post-prandial glucose target was 3.5-6.9 mmol/L.

Between June and December 2015, the glycaemic profiles of 120 consecutive women with GDM at 36 weeks’ gestation attending the antenatal clinic were assessed, and their fasting as well as the 2 h postprandial blood glucose levels (BGLs) in the previous 4 weeks was documented. All BGL readings were derived from the woman’s blood glucose meter.

Regression analysis was used to compare relationship between HbA1c and glucose parameters. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Informed consent was obtained from the women and the study was approved by South Western Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee.

Results

The mean HbA1c of the women at 36 weeks’ gestation was 5.6 ± 0.6% (38 ± 7 mmol/mol) and all had haemoglobin levels above 110 g/L. The women had a mean age of 32.8 ± 5.4 years, with a mean body mass index (BMI) of 27.9 ± 6.5 kg/m2 and 52 of them (43.3%) required insulin therapy. The age, BMI and insulin requiring rate for our cohort was not different from other women with GDM at this institution in the past 5 years.

HbA1c at 36 weeks’ gestation was not associated with the women's age, BMI or presence of family history of diabetes. Women who were on insulin therapy had a higher HbA1c than those who are on diet control (5.8 ± 0.7 [40 ± 8 mmol/mol] vs. 5.5 ± 0.4% [37 ± 4 mmol/ mol], p=0.017).

From data extracted from the glucose meter, the mean fasting BGL was 5.1 ± 0.6 mmol/L while the mean post-prandial BGL was 6.1 ± 0.6 mmol/L (combination of post-breakfast, post-lunch and post-dinner readings). There were only a total of 10 BGL readings that were below 3.5 mmol/L, but all were above 3.0 mmol/L.

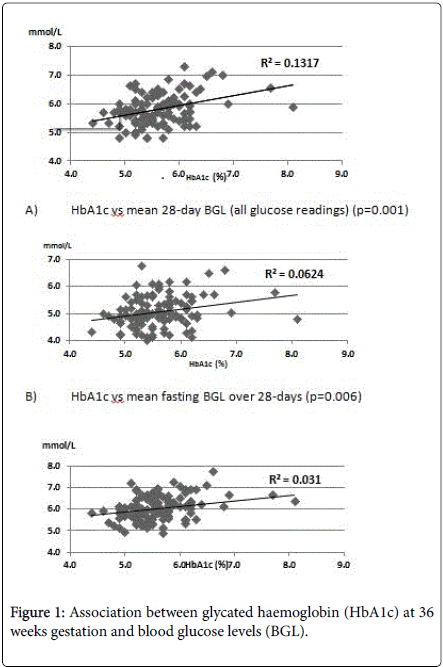

The 36 week HbA1c was found to have a positive but weak correlation with the women’s overall mean BGL over the prior 28 days, their mean fasting BGLs or the mean post-prandial BGLs over the same period (Figure 1). Removal of the outliers (HbA1c 8.1% [65 mmol/mol] and 7.7% [61 mmol/mol]) did not alter the association of HbA1c with BGLs.

Using treatment targets of 3.5-5.4 mmol/L for fasting BGL and 3.5-6.9 mmol/L for 2 h post-prandial BGL (Target 1), the mean proportion of BGLs above treatment targets for each woman was 17.3 ± 16.0%.

When HbA1c values were divided into quartiles [Quartile 1, <5.2% (<33 mmol/mol); Quartile 2, 5.2-5.5% (33-37 mmol/mol); Quartile 3, 5.6-5.9% (38-41 mmol/mol) and Quartile 4, >5.9% (>41 mmol/mol)], there was step-wise increase in the proportion of BGLs above treatment targets for subject across the HbA1c quartiles (12.9, 13.6, 18.6 and 23.7%, p=0.003).

Using another set of glucose targets that were more stringent (fasting BGL 3.5-5.2 mmol/L and 2 h post-prandial BGL 3.5-6.6 mmol/L – Target 2), there was similar increase in the proportion of BGLs above these targets from quartile 1 to quartile 4 (20.8, 22.1, 30.1, 35.3%, p<0.001).

At this institution, insulin therapy is often initiated when >20% of BGLs are above targets. In this cohort, amongst women with GDM who were on diet control only (n=68), the percentage of women with over 20% of BGLs above targets (for both Targets 1 and 2) increased across the HbA1c quartiles (Table 1).

| Subjects with >20% of glucose readings above target | Quartile 1 N=18 (%) | Quartile 2 (N=27) (%) | Quartile 3 (N=9) (%) | Quartile 4 (N=14) (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target 1 | |||||

| Fasting BGL 3.5-5.4 mmol/L or 2 h post-prandial BGL 3.5-6.9 mmol/L | 0 (0) | 7 (25.9) | 3 (33.3) | 6 (42.9) | 0.004 |

| Target 2 | |||||

| Fasting BGL 3.5-5.2 mmol/L or 2 h post-prandial BGL 3.5-6.6 mmol/L | 4 (22.2) | 13 (48.2) | 5 (55.6) | 8 (57.2) | 0.049 |

Table 1: For women on diet control, number and percentage of women with >20% of their blood glucose levels (BGLs) above 2 sets of glucose targets, according to the different glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) quartiles (Quartile 1: HbA1c<5.2% (<33 mmol/mol); Quartile 2: HbA1c 5.2-5.5% (33-37 mmol/mol); Quartile 3: HbA1c 5.6-5.9% (38-41 mmol/mol); Quartile 4: HbA1c >5.9% (>41 mmol/mol)).

Discussion

Currently, regular SMBG is the standard tool for assessing glycaemic profile in women with GDM. Women with GDM usually have to perform 4 BGL readings a day and although compliance to SMBG is generally good, some women are unable to fulfil this task. For women with GDM, falsification of BGLs on logbooks is well known, with over 20% of BGLs not accurately documented in one study [7]. Sometimes when obstetric ultrasound demonstrates macrosomia or polyhydramnios – features that may suggest suboptimal maternal glycaemic control, it would be invaluable to have an alternate way to assess glycaemic status of the women rather than relying solely on their BGL records from SMBG. The use of continuous glucose monitoring system is a promising tool, but it is expensive and may not be acceptable for some pregnant women [8,9].

To date, various guidelines for managing GDM have not recommended using HbA1c to assess the level of glycaemic control during pregnancy [5,6]. Indeed, HbA1c is often interpreted with caution when measured during pregnancy, as pregnant women are prone to anaemia and iron deficiency. The normal range for HbA1c during pregnancy is also not clearly defined, and is thought to change across trimesters [10]. For women who do not have pre-existing diabetes, a few studies had looked at the relationship between HbA1c and pregnancy outcomes. In a Spanish study of over 2000 women with GDM, those with third-trimester HbA1c above 5.0% had a greater risk for large-for-gestational-age neonates and other neonatal complications [11]. Similarly, in an Australian study of women with GDM, elevated HbA1c at diagnosis of GDM as well as at 36 weeks were both predictors of macrosomia and neonatal hypoglycaemia [3].

Rather than to examine the association between HbA1c and clinical outcomes in pregnancy, the aim of this study is to assess how HbA1c correlates with BGLs for women with GDM in third trimester. In the literature, there is little information on the relationship between BGLs from SMBG and HbA1c in this population. There were studies that assessed the association between glucose levels on OGTT and HbA1c, and the relationship has not been clear [12]. In this study, 36 week HbA1c was found to have only a weak association with the mean, fasting as well as post-prandial BGLs from blood glucose monitoring over the previous 4 week period. However, women in the higher HbA1c quartiles had greater proportion of BGLs that exceeded treatment targets. The patterns were similar when 2 different sets of treatment targets were used. Although it would be difficult to initiate insulin therapy or titrate insulin doses based on elevated HbA1c alone (without adequate BGL readings), it may be reasonable to consider alternate therapy such as metformin in these women, especially when their HbA1c is above 5.9% (41 mmol/mol), the highest HbA1c quartile in this study. In women who are non-compliant with SMBG, an elevated HbA1c may be taken into consideration when planning the timing of delivery in conjunction with other maternal/fetal factors.

Limitations

There are some limitations with this study. First, only BGLs over the previous 28 days period were recorded, but HbA1c may reflect glycaemic profile for a longer period of time in pregnancy. Secondly, the study did not take into account of women who had varying glucose profiles during the 28 days. Some women may have suboptimal glycaemic control in the first 2 weeks but had better BGLs in the subsequent 2 weeks due to improvement in diet and introduction of insulin therapy. How that may impact on HbA1c is unclear. Furthermore, the relationship between BGLs and HbA1c performed at an earlier gestational age could not be inferred from this study. Finally, the validity of HbA1c in women with haemoglobinopathy, haemolysis, anaemia, or iron deficiency during pregnancy could not be confirmed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study showed that 36 week HbA1c has weak association with fasting and/or post-prandial BGLs, but an elevated HbA1c can identify women who have more glucose readings that exceed treatment targets in the previous 4 weeks. Although HbA1c cannot replace SMBG, it can still provide useful information for clinicians, especially when the woman is not reliable in performing glucose monitoring.

References

- Macintosh MC, Fleming KM, Bailey JA, Doyle P, Modder J, et al. (2006) Perinatal mortality and congenital anomalies in babies of women with type 1 or type 2 diabetes in England, Wales and Northern Ireland: Population based study. BMJ 333: 177.

- Galindo A, Burguillo AG, Azriel S, Fuente Pde L (2006) Outcome of fetuses in women with pregestational diabetes mellitus. J Perinat Med 34: 323-331.

- Wong VW, Chong S, Mediratta S, Jalaludin B (2016) Measuring glycated haemoglobin in women with gestational diabetes mellitus: How useful is it? Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol.

- Hughes RC, Rowan J, Florkowski CM (2016) Is there a role for HbA1c in pregnancy? Curr Diab Rep 16: 5.

- American Diabetes Association (2014) Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 37: 81-90.

- Nankervis A, McIntyre HD, Moses R, Ross GP, Callaway L, et al. (2013) ADIPS consensus guidelines for the testing and diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus in Australia.

- (2014) Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 37: 81-90.

- Kendrick JM, Wilson C, Elder RF, Smith CS (2005) Reliability of reporting of self-monitoring of blood glucose in pregnant women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 34: 329-334.

- Kestila KK, Ekblad UU, Ronnemaa T (2007) Continuous glucose monitoring versus self-monitoring of blood glucose in the treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 77: 174-179.

- O'Shea P, O'Connor C, Owens L, Carmody L, Avalos G, et al. (2012) Trimester-specific reference intervals for IFCC standardised haemoglobin A(1c): New criterion to diagnose gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)? Ir Med J 105: 29-31.

- Buhling KJ, Kurzidim B, Wolf C, Wohlfarth K, Mahmoudi M, et al. ( 2004) Introductory experience with the continuous glucose monitoring system (CGMS; Medtronic Minimed) in detecting hyerglycaemia by comparing the self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) in non-pregnant women and in pregnant women with impaired glucose tolerance and gestational diabetes. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 112: 556-560.

- Mert M, Purcu S, Soyluk O, Okuturlar Y, Karakaya P, et al. (2015) The relationship between glycated haemoglobin and blood glucose levels of 75 and 100 g oral glucose tolerance test during gestational diabetes diagnosis. Int J Clin Exp Med 8: 13335-13340.

Relevant Topics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 3296

- [From(publication date):

June-2017 - Dec 18, 2024] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 2552

- PDF downloads : 744