Diversity Checkup: A Study of Multicultural Medicine

DOI: 10.4172/2161-0711.1000716

Abstract

Objective: The failure to provide quality, patient centered healthcare has been directly associated with a lack of cultural diversity within the healthcare system itself [1]. The present study aims to capture community perceptions related to the lack of diversity in the Oregon healthcare system in an effort to determine what steps can and should be taken to promote more culturally sensitive healthcare. The purpose of this study was to find what the underlying attitudes on diversity in healthcare are, what role diversity plays in the healthcare we give and receive, and what can be done to increase diversity in healthcare.

Methods: A total of 767 healthcare workers, high school students, college students, and patients completed an online survey of attitudes on diversity in healthcare. The survey included a combination of close ended and open ended questions. Upon completion of the first survey, all respondents were invited to participate in a second survey that allowed them to elaborate on previous responses related to their personal experiences navigating diversity in healthcare.

Results: Most healthcare workers who participated in the survey identified as white/Caucasian, with very few respondents identifying with a racial minority. The majority of all participants noted they did not believe all patients are treated equitably on the basis of diversity, and many believed the lack of healthcare worker diversity contributed to this. Furthermore, among ethnically over and underrepresented college and high school students, lack of funding and lack of mentorship were deemed to be the most notable factors keeping them from pursuing a career in healthcare

Keywords: Diversity; Healthcare; Inequities; Pre-Health; Mentorship; Equity; Underrepresented

Introduction

Overview of diversity

The Oxford English Dictionary defines diversity as the condition or quality of being diverse, different, or varied. In the social sciences, diversity is best defined as “a successful community in which individuals of different race, ethnicity, religious beliefs, socioeconomic status, language, geographical origin, gender and/or sexual orientation bring their different knowledge, background, experience and interest for the benefit of their diverse community [2].”Recent events have shed light on the current divide between perceptions of diversity vs actual diversity. Though organizational and institutional efforts to be more inclusive are seemingly on the rise, several national studies have still found there to be a significant lack of diversity in most professional and academic establishments. This lack of diversity, however, is usually not the result of an insufficient desire by these establishments to be catalysts for change, but rather numerous barriers that pose significant challenges to implanting and upholding increased diversity efforts. A previous study identified three barriers most often run into in the effort to implement measures to promote more diversity: poor information and communication, lacking awareness and knowledge of diversity, and organizational constraints [3].

It is estimated that until the year 2050, people of color will contribute to around 90% of population growth in the US [4]. This same time frame is also expected to mark the first time in US history that people of color become the majority, with the population of whites dropping drastically [5]. Our nation is becoming increasingly racially and ethnically diverse and the representatives of the organizations and institutions in our nation reflect this increasing diversity. While a push for more diversity on the basis of social justice is certainly relevant and important, there are also many benefits to being more diverse. The underserved and minority populations have been shown to characteristically give back through community building and provide more emotional and financial support for other underserved and minority groups than their overserved and majority counterparts [6].

According to 2020 US Census, approximately 50.8% of the US population is female yet many organizations still fail to create a diverse workplace environment that reflects the gender distribution of the US population. Discriminatory application and interview processes are still in place across multiple establishments and states to impede those who do not identify as male from being hired [7]. The fight for more gender diversity in the workplace has been fought using an economic and a political angle. From the political angle, it is inequitable that females make up half of the population but a small portion of organizational leaders and those who are so fortunate to be placed in a position of power receive lower wages than their male identifying counterparts. From the economic angle, studies have shown that organizations in gender balance are more productive, and more productive organizations are statistically shown to be more profitable [8].

Foundations for more healthcare diversity

Those who identify as white/Caucasian make up approximately 77% of the Oregon population [9] yet they make up approximately 82.8% of the clinical healthcare workers [10]. In Oregon, minority groups comprise the remainder of the population, but they represent only a fraction of healthcare workers. In fact, nationally, less than 8% of physicians identify as African American, around 6% identify as Hispanic, and only 0.56% of physicians identify as American Indian/ Alaska Native [11]. However, over the last few years, these numbers are decreasing at a rapid rate, with only 4% of practicing physicians identifying as Black or African American [12]. These discouraging numbers have led diversity and inclusion efforts to become the focus of many major health organizations to further diversity efforts. Racial and ethnic diversity is just one facet of diversification that healthcare systems are failing to meet effectively.

Gender diversity is also becoming increasingly narrow among healthcare workers, with females making up 90% of nursing professionals and males making up 68% of physicians. Medical resident data suggest that this gender gap is even more pronounced among specialties: surgical specialties are 80% male while specialties such as dermatology and pediatrics are over 60% female [13]. Furthermore, while only 4% of practicing physicians identify as Black or African American, only 2% of the 4% of physicians also identify as female [12].

The patient provider interaction

Regardless of accessibility, minority populations are subject to a lower quality of treatment and fewer healthcare services compared to majority populations [5]. Given this, it is not surprising that previous research has also found that racial and ethnic minority patients are more likely to seek out healthcare professionals of their same race or ethnicity. Additionally, these patients not only report being more satisfied with their care but report they receive a higher quality of care when they are treated by individuals of their own race or ethnicity [1]. Sociocultural differences between a patient and the healthcare team serving them can negatively impact clinical outcomes [14]. Differences in biases and knowledge of various patient populations from healthcare workers have led to more medical mistakes, untreated illnesses, and improper treatments. Moving forward, these same issues could be preventable if healthcare workers had a better understanding of more diverse groups of people [2]. Yet, it is not feasible for healthcare providers to be culturally competent of every race, ethnicity, religion, and sexual orientation’s needs and desires, making the need for a more diverse group of healthcare workers the best way to achieve equitable healthcare for all [15].

The US is among the wealthiest nations yet one of the sickest nations. The health of the US population is similar to that of a much poorer nation, and this is believed to be a reflection of the poor job healthcare systems are doing addressing the needs of minority, obese, and economically disadvantaged groups [16]. Those of low socioeconomic status (SES) and or racial, ethnic, or sexual minorities tend to have more exaggerated conditions that lead to their deteriorating health, and yet on average, they have been found to receive either no care or low quality care [17]. This low quality of care has been met with severe distrust of the medical community by minority groups. Around 15% of minority groups have felt they were not treated respectfully by the healthcare workers they have interacted with and over 50% of those who identify as a minority have noted that they do not have confidence or trust in their healthcare providers. Patient success inside and outside of the hospital is largely dependent upon the patient and provider relationship and studies have indicated that patients are more likely to follow medication regimens and other instructions when they trust their physician [18]. According to the Commonwealth Fund (2002), up to 15% of minority groups have expressed that they believe they would receive better quality healthcare if they were of a different race, compared to only 1% of whites sharing this same belief. Overall, it has been found that among every measure of good healthcare, there is a distinct difference between the experiences of minority groups and whites.

Community among healthcare workers

Healthcare systems with strong interprofessional collaboration have been shown to have greater efficiency, lower costs, and often provide better patient care resulting in better patient outcomes [19]. Minority healthcare professionals are few and far between in roles of greater authority, such as provider and administrative roles, but those who do serve in these roles not only seek to provide better patient care for minority populations, but their presence serves as an encouragement to students, patients, and their fellow minority healthcare workers [20]. Researchers found that when asked who exhibits poor behavior, such as insulting fellow healthcare workers and expressing degrading comments in front of patients, 45% of respondents agreed physicians exhibited such behavior compared to only 7% suggesting nurses display this same behavior [13]. Minority groups are more represented in support staff and nursing roles compared to provider roles, suggesting that decreased diversity among providers may lead to great rates of poor interprofessional interactions [21].

Healthcare workers feel that increased diversity among the care team leads to different perspectives and better collaboration. Likewise, when the care team is less diverse, healthcare workers have reported feeling dissatisfied with team communication and have reported more internal conflict among team members [2]. Both gender balanced teams and racially/ethnically diverse teams have been shown to be more productive, are more creative, and collaborate more positively than teams that are gender unbalanced and are less racially/ethnically diverse [8].

Increasing healthcare diversity from the bottom up

The need for more diversity in healthcare is undeniable. Prior research has found that minority students at the high school and baccalaureate level tend to fare worse off in science and math based courses compared to white students [22]. These statistics are not the result of lower competency, but rather a combination of socioeconomic and environmental factors along with faculty/peer interactions. Not only are minorities less likely to seek out pre-health programs, but they are more likely to choose not to go to college and those who do go to college are less likely to earn their degree compared to white students [23]. It has been found that minority students face several challenges that keep them from pursuing healthcare careers early on in their education and these challenges persist throughout high school and college. Some of the main barriers that have been isolated as contributing factors to the lack of diversity among pre-health students are academic challenges, motivation, and advisement [24].

Statistically, it has been shown that minority children are often raised and attend school in areas of low socioeconomic status. These schools have fewer resources which leave them unable to provide access to guidance and mentorship that could lead minority groups to pursue careers in healthcare. In fact, African American children have a higher probability of ending up in prison than they do in college and this is a result of the education system they are put through [25]. Compared to their non-black peers, African American students are, on average, more likely to be educated in inner city public school systems that do not have the funding to provide as high quality education as public schools in suburbs or private schools. Despite this, one study found that minority students were more likely than their white peers to complete the requirements to apply for graduate and doctoral programs that would lead them to a healthcare career, yet on average their lower scores in these core courses led to lower acceptance rates compared to white students [26]. The growth of minority applicants, matriculants, and graduates of competitive graduate and doctoral programs, such as medical school, has remained stagnant for several years. Minority students who do apply and matriculate into medical schools are met with not only a predominantly white group of peers but with 64% of their faculty identifying as white and 59% identifying as male [27]. This lack of diversity leads many students to feel secluded and often results in lower scores compared to their white peers.

Several studies have proposed multipronged approaches to addressing the lack of cultural diversity among healthcare workers. Everything from the rewriting of admissions policies to developing a more culturally competent baccalaureate level program in ‘health humanities,’ has been proposed [28]. Perhaps the most promising of these proposals, however, is K-12 education pipeline reform along with increased access to mentoring for minority and underserved students wanting to become healthcare professionals [29]. Pipeline programs that focus their efforts on enhancing student engagement in key classes and provide more guidance for minority students who want to seek out a career in healthcare have been shown to be extremely successful and may hold the answer to increasing the rates of minority healthcare professionals [23]. Mentorship has been shown to increase a desire and perceived ability in the mentee to pursue a career in the same field as their mentor. In a recent study, 16 pairs of high school student mentees and 2nd or 3rd year medical student mentors participated in a Medical School Mentorship Program. Immediately after participation, all mentees reported an increased desire to pursue a career in healthcare, and in a follow up study years later, each mentee reported being on a pre-health career track at their college or university [30].

A similar study also proposed health professional schools and the public school system form a partnership to increase student exposure to careers in healthcare. Such a program would benefit all students, especially those of minority backgrounds who generally have little to no access to the resources they need to pursue a career in healthcare. The proposed program would focus its effort on exposure to pre-health pathways along with an enhanced effort to guide students to success in their science and math based courses needed to become a healthcare professional, one of the main struggles for minority students [31]. Additionally, researchers found a significant increase in the interest to pursue a career in healthcare from students who originally did not express interest after a health career pathway program was initiated for minority students [32]. These studies have shown a correlation between accessibility, mentorship, and minority student success in such a way that could help further healthcare diversity efforts.

Research questions

Much research has been conducted studying the role diversity plays in the workplace, among patient provider interactions, and among healthcare workers. However, less research has been conducted on the connection between diversity in healthcare and what can be done to improve upon the lack of diversity. Progress cannot be made without cultural humility, and to gain this knowledge it is imperative that research is aimed at discovering what the underlying attitudes on diversity in healthcare are, what role diversity plays in the healthcare we give and receive, and what can be done to increase diversity in healthcare [33].

Methods

Measures

The purpose of this research study was to capture community perceptions related to the lack of diversity in the Oregon healthcare system to determine what steps can and should be taken to promote more diverse healthcare. The collection of responses was split into four separate surveys, one for each group of participants: healthcare workers, college students, high school students, and patients (Appendix A). Each survey had a combination of ~30 questionnaire and open ended questions. The questions being asked ranged from demographics to personal and/or shared experiences, and overall attitudes/opinions on diversity in healthcare.

Specifically, the healthcare worker survey had 32 questions, of which, 7 items were related to participant demographics, 15 items were related to personal experiences with diversity in healthcare, and the remaining 10 items were related to overall feelings about diversity in healthcare. The college student survey had 30 questions, 10 items were demographic in nature, 15 items were concerning personal experiences with diversity in healthcare, and 5 were related to overall feelings about diversity in healthcare. The high school student survey had 29 questions, 11 items were demographic, 13 items were based on personal experiences with diversity in healthcare, and the last 5 were related to perceptions of diversity in healthcare. Lastly, the patient survey consisted of 24 questions, of these, 2 items were demographic, 12 items were related to personal experiences with diversity in healthcare, and the remaining 10 were concerning overall attitudes about diversity in healthcare.

bvAt the end of every survey, all participants were asked if they would like to share more about their experiences, thoughts, and opinions on diversity in healthcare. Participants who selected ‘no’ were directed to the end of the survey. Participants who elected to participate were directed to a separate survey with 7 open ended questions that asked about general ideas and attitudes on healthcare diversity (Appendix B). These questions ranged from a general definition of diversity to how the respondent felt diversity impacted healthcare.

Participants

The population sampled for this study consisted of 4 groups of people. Responses were collected from healthcare workers, college students, high school students, and patients to get a wide reaching sample of people with varying degrees of healthcare experiences. Participant recruitment from various community organizations, colleges/universities, high schools, and healthcare systems was done via email. Willing representatives from these various establishments were given the appropriate survey link along with a short description of the project to send out to their members, faculty, staff, volunteers, and/or students.

Of the 767 responses, 232 belonged to healthcare workers, 259 belonged to college students, 98 belonged to high school students, 92 belonged to patients, and 86 responses were collected from the secondary survey.

Procedure

At the beginning of each survey, participants were given the opportunity to read a consent form that included the potential for discomfort that could result from answering certain questions. Participants were given the contact information of the primary investigator, along with contact information for mental health resources. Before filling out the survey, all participants were asked to confirm that they had read and understood the consent form and were 18 years of age or older at the time of participation. Participants were made aware that they were not required to answer all of the questions and could withdraw their consent and responses at any time. All survey responses were anonymous, and participants were notified of the anonymity of the survey before they began. No personal identifying information was asked for and therefore not attached to any survey responses, except for basic demographic information. Participants were encouraged to only answer the questions they felt comfortable answering and to select the answers that were most applicable concerning their thoughts and opinions.

All participants were issued a written informed consent and agreed to participate after reading this consent form. All data collected as a part of these surveys has been included with this manuscript.

Results

The sample size included 767 responses from participants who identified as either a healthcare worker (n=232), college student (n=259), high school student (n=98), or patient (n=92) and participants who were willing to participate in the secondary survey (n=86). Of the 232 healthcare workers that participated, 208 (90%) did not indicate Latinx or Spanish origin and 180 (78%) identified as white/ Caucasian (Table 1). A total of 160 (69%) of the healthcare workers’ responses were collected from physicians from a wide variety of specialties, including emergency medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics. Females comprised 58% (n=134) of the healthcare worker response, males comprised 40% (n=92) of the responses and only 2% (n=5) respondents identified as either a different gender or chose not to disclose their gender (Table 1).

| Healthcare Workers (232) | College Students (259) | High School Students (98) | Patients (92) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race White/Caucasian Asian or Asian American Black or African American Native American/Alaska Native Native Hawaiian/ Pacific Islander Other/Chose not to Respond |

78% (181) 9% (21) 5% (12) 0.4% (1) 1% (2) 6.6% (15) |

66% (170) 20% (52) 3% (8) 3% (8) 3% (8) 5% (13) |

51% (50) 31% (30) 9% (9) 1% (1) 0% (0) 8% (8) |

78% (72) 6% (6) 4% (4) 3% (2) 1% (1) 8% (7) |

| Ethnicity Not Latinx or Spanish Origin |

90% (209) | 74% (192) | 79% (77) | 85% (78) |

| Gender Identity Male Female Other |

40% (93) 58% (135) 2% (4) |

15% (39) 83% (215) 2% (4) |

20% (20) 79% (77) 1% (1) |

32% (29) 67% (62) 1% (1) |

Table 1: Gender, Race, and Ethnicity of Participants.

As can be seen in Table 2, high school students in their senior year comprised 80% (n=78) of the 98 responses, and only 6% (n=5) identified as either a freshman or a sophomore. Approximately 79% (n=77) of responses were from respondents who identified as female. A total of 49 high school students (51%) identified as white/Caucasian and 30 (31%) identified as Asian or Asian American. Of the 98 high school student respondents, 77 (79%) did not identify as having Latinx or Spanish origin (Table 1). College students had similar demographics, with 83% (n=214) identifying as female and 66% (n=170) identifying as white/Caucasian. Of the 259 respondents, 74% (n=191) did not identify as having Latinx or Spanish origin (Table 1). The majority of college student respondents (56%) currently attend University of Portland, and the distribution of college student responses was even among freshman, sophomore, junior, and senior standing students (Table 2). Patients had a distribution similar to the other 3 groups, with 71 (78%) respondents identifying as white and 61 (67%) respondents identifying as female. Of the 92 patients who responded to the survey, 85% did not identify as having Latinx or Spanish origin (Table 1).

| Percent | |

|---|---|

| High School Student School (98) Rex Putnam Clackamas Web Academy Westview High Clackamas High Other |

2% (2) 20% (20) 27% (26) 6% (6) 45% (44) |

| High School Student Year (98) Freshman Sophomore Junior Senior Other |

4% (4) 2% (2) 14% (14) 80% (78) 0% (0) |

| College Students School (259) University of Portland Pacific University George Fox University Warner Pacific University Lane Community College Other College Student Year (259) Freshman Sophomore Junior Senior Other |

56% (145) 23% (60) |

Table 2: Student School Demographics.

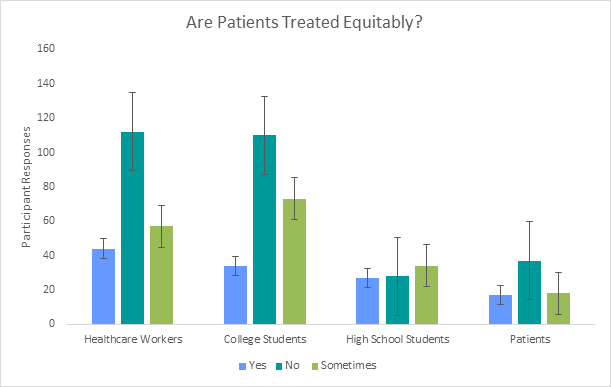

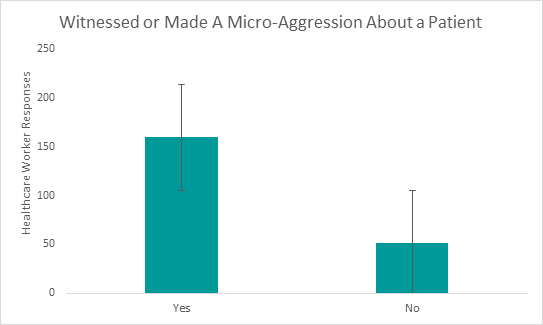

When asked if they feel that all patients, regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, or religious affiliation are treated equitably, over 40% of participants (n=287) suggested that all patients are not treated equitably. The negative reaction to this question was noticed most drastically among college student respondents, with only 13% (n=34) of participants indicating that they believe all patients are treated equitably, compared to 43% (n=110) who indicated they do not believe all patients are treated equitably (Figure 1). Furthermore, when asked if they have made or witnessed microaggression being made to or about a patient, 69% (n=160) of healthcare workers said yes, 22% (n=51) said no, and 9% (n=21) of respondents chose not to answer (Figure 2).

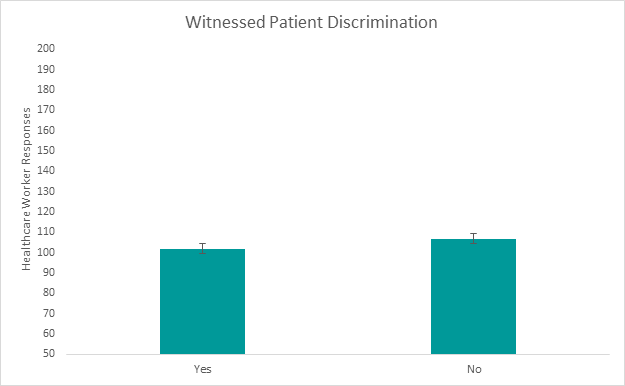

However, when asked if they had ever witnessed a patient being given less attention, lower quality of treatment, or fewer resources due to their race, ethnicity, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, or religious affiliation, healthcare workers had a split response with 102 (44%) answering, yes, 107 (46%) answering no, and 23 (10%) choosing not to respond (Figure 3).

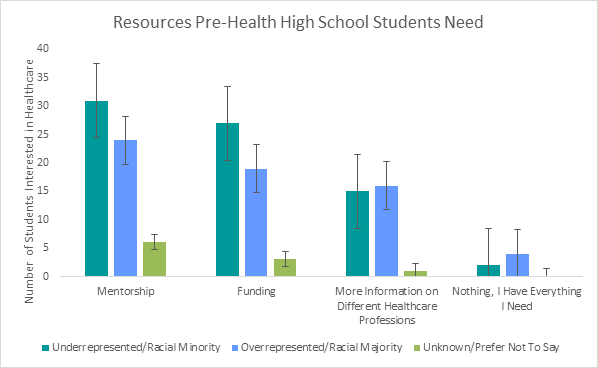

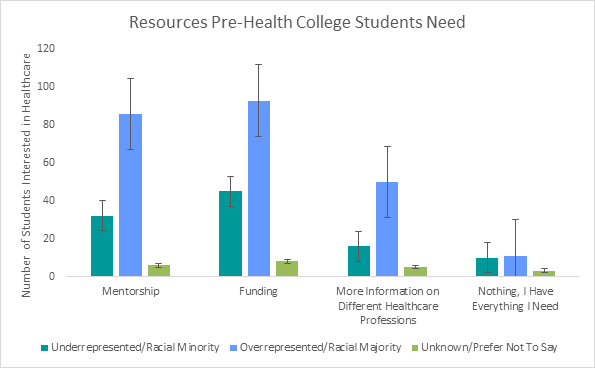

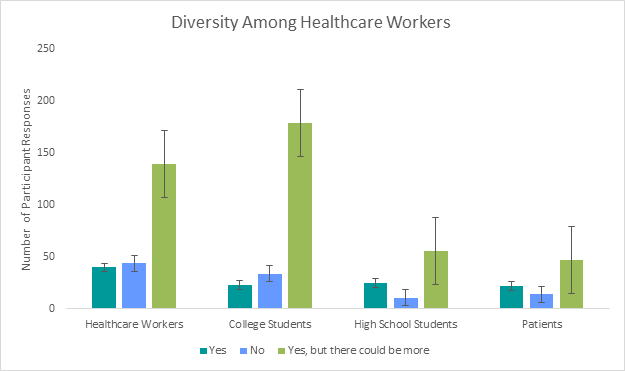

College and high school students who indicated an interest in becoming healthcare professionals were asked to select the resources they did not already have that they felt would be most beneficial to their success as pre-health students. Only 7.6% of both college and high school students (n=27) indicated they had everything they needed to be successful pre-health students. Overall, among both ethnically underrepresented and ethnically overrepresented college students, funding was the resource most students (n=146) felt they needed in order to be successful (see Figure 4). In contrast, among both ethnically underrepresented and ethnically overrepresented high school students, mentorship was the resource most students (n=61) felt they needed in order to be successful (Figure 5).

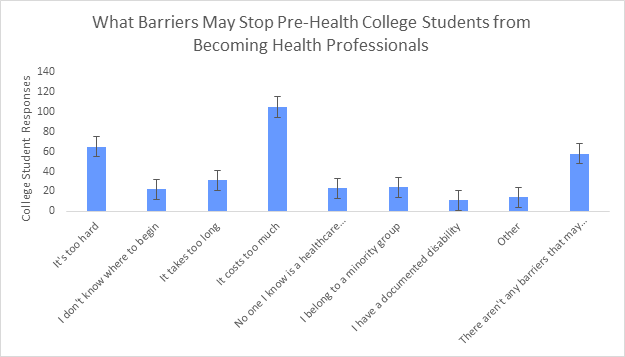

When pre-health college students were asked what barriers could prevent them from becoming a health professional 41% (n=105) expressed the cost of becoming a health professional was the main barrier that could keep them from becoming a healthcare professional. Of the 259 respondents, 14% (n=35) indicated that they belonged to a minority group or had a documented disability that may prevent them from becoming a healthcare professional. Approximately 22% (n=58) of respondents suggested that they had everything they needed, and nothing could prevent them from becoming a healthcare professional (Figure 6).

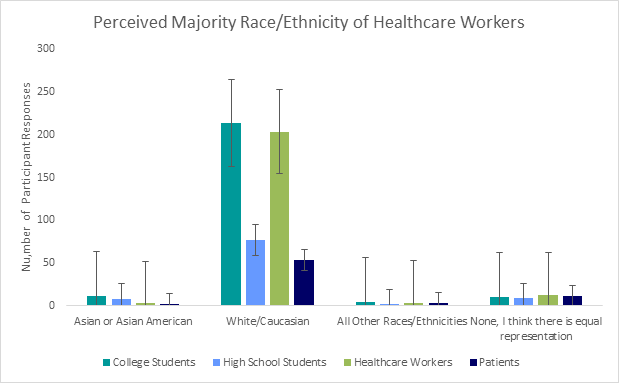

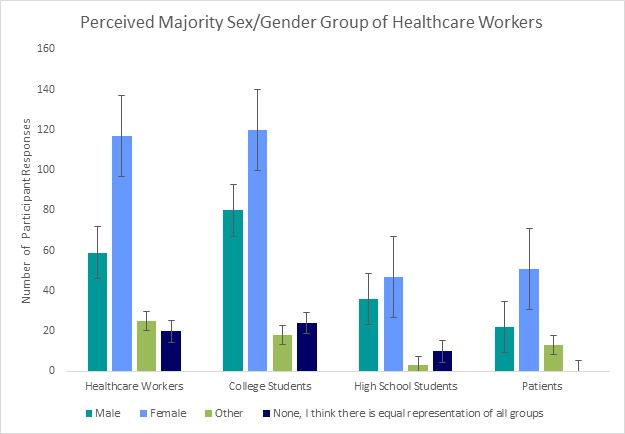

All participants were asked to identify the race/ethnicity they believed made up the majority of all healthcare workers. A total of 549 respondents believe that the majority of healthcare workers are white/ Caucasian, and only 45 respondents believe there is equal representation of all races/ethnicities in the current healthcare system (Figure 7). Participants were also asked to identify the gender/gender identity that they believe makes up the majority of healthcare workers. The majority of participants (n=335) believe that females make up the majority of healthcare workers while 197 participants believe males make up the majority of healthcare workers. Similar to responses from the perceived race/ethnicity of the majority of healthcare workers, only 54 respondents believe there is equal representation of all genders/gender identities.

A total of 86 responses were collected from the second survey that participants were given the opportunity to fill out if they had more to share on their experiences with diversity in healthcare. When asked to elaborate on their experiences with diversity in the current healthcare system, many participants noted that they have rarely seen healthcare providers of African American or Native American/Alaskan Native descent. Several respondents also noted the difference in gender among healthcare workers, indicating a higher rate of male physicians and female nurses. Overall, most respondents noted very little diversity among different gender identities and healthcare roles that held more authority. Additionally, several patients noted that diversity or the lack thereof can affect the way that they are given care or the way they follow up with their care. One respondent stated that “the lack of diversity impacts my attitude when it comes to the care that I receive. I don't feel welcomed or seen which impacts how I approach my care.” This was a reoccurring theme, with other respondents stating that “It’s hard to relate to health professionals when they don’t have our same background; it’s hard for them to give a proper diagnosis” or “How you can trust someone with perhaps your life if you feel constantly judged?”

Furthermore, when asked to describe the measures they think should be taken to further diversity efforts in healthcare, several respondents agreed that it was crucial to begin diversity efforts in early schooling, especially in high schools. One participant suggested that high school students should be encouraged “to do health occupation surveys where they spend time in different health care environments.” While other participants noted that “Programs that provide outreach and education on healthcare careers in underserved communities should be more active.”

Discussion

Most respondents were white/Caucasian and female, which is representative of the Oregon population [9]. Approximately half of the US population is female and well over half of Oregonians are white/ Caucasian. Additionally, the majority of healthcare workers who participated in the survey identified as white/Caucasian, with very few respondents identifying with a racial minority. According to the Oregon Health Authority, this is the case across the state, with over 80% of all healthcare workers identifying as white/Caucasian (2019). From the data collected the majority of healthcare worker respondents identified as a physician and approximately 9% of the physicians identified as African American, which is slightly higher than the national average of less than 8% of physicians identifying as African American. The amount of Native American/Alaska Native providers was nearly identical with 0.4% of respondents identifying as Native American/Alaska Native compared to the national average of 0.56% [11]. These findings stayed the same when all participants were asked to identify the perceived majority race of healthcare workers, with the vast majority of all respondents indicating that they believe most healthcare workers are white/Caucasian and male. When given the opportunity to elaborate on this answer, several participants noted that most physicians are male, most nurses are female, and very few healthcare workers identify as another gender. This is in concurrence with the findings of a recent study which determined that females make up nearly all of the nursing professionals and males make up well over half of all physicians [13] (Figure 8).

Overall, the belief that most respondents held in regard to the breakdown of diversity among healthcare workers did not fully hold to be true. The majority of the healthcare workers who responded was physicians and yet was majorly comprised of female respondents. However, most of the respondents were white/Caucasian, with very few respondents identifying with a minority race. Furthermore, the belief that most physicians are males and most nursing professionals are female could not be refuted nor supported given the low nurse respondent rate. The low turnout of nursing professional is believed to be in direct correlation to COVID-19 burnout resulting in less time and energy to complete the survey (Figure 9).

As for high school and college students, the majority of respondents identified as female and white/Caucasian. Most of the respondents were pre-health students, with a primary focus on pre-medical and pre-nursing. When asked if they felt they would be successful in their pre-health journey, nearly all respondents across both high school and college students identified a lack of resources and a lack of mentorship as what is holding them back from believing they can be successful as a pre-health student. Lack of funding and resources is not a surprising finding, given that the cost to go to college has only increased in recent years, and the cost to attend graduate programs is keeping students in debt for decades after they graduate. In regards to mentorship, previous studies have identified the overwhelming benefits to having a mentor as a pre-health student, especially for underrepresented and minority students [30].

Most respondents identified a lack of diversity in healthcare and expressed disappointment in the lack of retention efforts of diverse groups of pre-health students in elementary, middle, and high school. Of the respondents who identified a lack of diversity most also noted that they believe diversity could greatly improve if there was a larger emphasis placed on getting underrepresented and minority students interested in healthcare prior to graduating from high school. Some ideas including pre-health pipeline programs and once again, more access to opportunities for mentorship and exposure to the many healthcare professions. Financial incentives were also recommended by several respondents, as many underrepresented and minority students do not have the ability to take on the financial burden that comes with going to college and pursuing a career in healthcare.

When asked if all patients, regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, or religious affiliation are treated equitably, the majority of participants suggested that all patients are not treated equitably. These findings were similar to a 2017 study that found that those of low socioeconomic status (SES) and or racial, ethnic, or sexual minorities on average have been found to receive either no care or low quality care [17]. These findings also correlated directly to the responses garnered from healthcare workers, who majorly agreed that they had either made a microaggression towards a patient or witnessed a microaggression being made towards a patient.

This study was run entirely during the COVID-19 pandemic and all data was collected online. Outreach to organizations and potential participants were conducted online, posing a major limitation to the reach and scope of the project. Participants are much harder to reach exclusively online given that most all of the communication being done during this time is also online. Furthermore, the primary targets of these surveys were students and healthcare workers; however both groups are facing unprecedented levels of burnout in accordance with the COVID-19 pandemic. Another limitation to the study was the number of minority responses that were generated. In general, minority groups are becoming harder to survey because of the mistreatment and misuse of many prior survey results leading to a distrust in the survey process. Most of the participants were white/Caucasian, despite efforts to distribute the survey to diverse groups of people. Finally, to expand upon the findings of this study, it is crucial to expand the survey population to rural areas of Oregon, as well as across the nation. Population dynamics among white and non-white individuals varies greatly from urban to rural areas as well as across state lines.

Given that the study was conducted in its entirety during the COVID- 19 pandemic, the response rate was much higher than expected. Over 760 responses were collected among all of the surveys, and this data sample provided a much larger scope of the population and therefore a much more accurate representation of the beliefs of the population. In addition to this, all of the questions that were intended to be answered through this study were answered and the findings generated did support current research. Strength of this study was the composite nature of the sampling methods. Previous studies generally focus on one subset of a population and do not take into consideration the thoughts and opinions of the remainder of the population. This study was distributed to healthcare workers but also to patients, high school students, and college students. These groups were created in an effort to represent the primary groups affected by the lack of diversity in healthcare, and the study was successful in recruiting participants from all 4 groups. Finally, the data collected was both qualitative and quantitative in nature. This mixed methods approach allowed respondents to answer all the same questions while also allowing for individual thoughts and opinions to be expressed.

Overall, the findings from these surveys do seem to be in support of current research. An overwhelming majority of participants agreed that all patients are not treated equitably and that diversity in healthcare needs to be expanded upon. Many respondents noted that efforts to expand upon diversity must be taken as early as possible, but that beginning in middle or high school would impact the diversity of the healthcare system greatly. Based on the findings, many different paths can be taken to further diversity in healthcare. It seems that to raise up a new generation of more diverse healthcare workers it will be best to take a multipronged approach. An early childhood education mentorship program that continues throughout high school seems to have identifiable benefits and should leave a lasting impact on the healthcare system. Additionally, since many students indicated that the cost of becoming a healthcare professional has inhibited them from becoming a healthcare professional, potentially creating a national fund or scholarship that drastically reduces the cost of tuition for minority students, without the premise of demonstrated financial aid. However, the benefits of these tactics will not be seen for years to come, and diversity is overdue now. To compensate for this, mandatory diversity training of all healthcare professionals should be done annually. Furthermore, since many healthcare professionals indicated that they had or had heard a coworker use a microaggression towards a patient, a new reporting system should be implemented for these unfortunate moments. Currently, very little is being done to ensure healthcare is diverse, inclusive, and equitable, but with these measures, and with time, our healthcare system has the potential to become increasingly diverse, which will ultimately lead to better patient outcomes and a healthier Oregon.

Conclusion

The findings of these surveys identified current attitudes on healthcare diversity, areas of discrimination and bias, and areas that can be changed to address the challenges associated with the lack of diversity in the healthcare system. The results can be used to advance pre-health professional programs for students and to further the diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts of health systems.

Acknowledgment

We thank MIKE Program of Portland Oregon, University of Portland, Legacy Health System, Providence Health and Services, George Fox University, Pacific University, Lane Community College, and Portland Public Schools.

References

- Scherman J (2017) Is a lack of cultural diversity in healthcare harming our patients? Rasmussen University.

- Pearson A, Srivastava R, Craig D, Tucker D, Grinspun D, et al. (2007) Systematic review on embracing cultural diversity for developing and sustaining a healthy work environment in healthcare. Int J Evid Based Healthc 5(1): 54-91.

- Celik H, Abma TA, Widdershoven GA, Van Wijmen FC, Klinge I (2008) Implementation of diversity in healthcare practices: barriers and opportunities. Patient Educ Couns 71(1):Â 65-71.

- Armada AA, Hubbard MF (2010) Diversity in healthcare: time to get real. Front Health Serv Manage. 26(3): 3-17.

- Wilbur K, Snyder C, Essary AC, Swapna R, Will KK, et al. (2020) Developing workforce diversity in the health professions: a social justice perspective. Health Prof Educ 6(2): 222–229.

- Grumbach K, Mendoza R (2008) Disparities in human resources: addressing the lack of diversity in the health professions. Health Aff 27(2): 413-422.

- Bosak J, Sczesny S (2011) Gender bias in leader selection? evidence from a hiring simulation study. Sex roles 65(3): 234-242.

- Vanderbroeck P, Wasserfallen JB (2016) Managing gender diversity in healthcare: getting it right. Leadersh Health Serv. 30(1): 92-100.

- Oregon’s Demographic Trends (2019) Oregon Office of Economic Analysis.

- The diversity of Oregon’s licensed health care workforce (2019) Oregon health authority.

- Goode C, Landefeld T (2018) The lack of diversity in healthcare: causes, consequences, and solutions. J Best Pract Healt Prof Div 11(2): 73-95.

- Roy L (2020) ‘It’s my calling to change the statistics’: why we need more black female physicians. Forbes.

- Ulrich B (2010) Gender Diversity and Nurse-Physician Relationships. Virtual Mentor 12(1): 41–45.

- Betancourt J, Green AR, Carillo JE (2000) The challenges of cross-cultural healthcare-diversity, ethics, and the medical encounter. Bioethics Forum 16(3): 27-32.

- Jhutti JJ (2013) Understanding and coping with diversity in healthcare. Health Care Anal 21(3): 259–270.

- Williams DR, Wyatt R (2015) Racial bias in health care and health: challenges and opportunities. JAMA 314(6): 555–556.

- FitzGerald C, Hurst S (2017) Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 18(1): 19.

- Alltucker KUT (2020) U.S. doctor shortage worsens as efforts to recruit Black and Latino students stall. USA TODAY.

- Gambino KM, Frawley S, Lu WH (2020) Addressing cultural diversity, patient safety, and quality care through an interprofessional health care course. Nurs Educ Perspect 41(6): 370–372.

- Livingston S (2018) Racism is still a problem in healthcare’s c-suite. J Best Pract Healt Prof Divers 11(1): 60–65.

- Sex, race and ethnic diversity of U.S. Health occupations (2017) us department of health and human services.

- Oyewole SH (2001) Sustaining minorities in prehealth advising programs: Challenges and strategies for success. The Nat Aca Press 281-304.

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Colburn L, Evans CH (2001) The right thing to do, the smart thing to do. Enhancing diversity in the health professions. In In: the right thing to do, the smart thing to do: enhancing diversity in the health professions–summary of the symposium on diversity in health professions in honor of Herbert. The Nat Aca Press 1: 35.

- Tucker CR, Winsor DL (2013) Where extrinsic meets intrinsic motivation: An investigation of black student persistence in pre-health careers. Negro Educational Review 64: 37-57.

- Brownlee D (2020) Why are black male doctors still so scarce in America? Forbes.

- Alexander C, Chen E, Grumbach K (2009) Minority student achievement in college gateway courses. Acad Med 84(6): 797-802.

- Berry S, Jones T, Lamb E (2017) The future of pre-health education is here. J Med Humanit 38: 353–360.

- Glazer G, Tobias B, Mentzel T (2018) Increasing healthcare workforce diversity: Urban universities as catalysts for change. J Prof Nurs 34(4): 239–244.

- Patel SI, RodrÃguez P, Gonzales RJ (2015) The implementation of an innovative high school mentoring program designed to enhance diversity and provide a pathway for future careers in healthcare related fields. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 2(3): 395–402.

- Patterson DG, Carline JD (2006) Promoting minority access to health careers through health profession–public school partnerships: a review of the literature. Acad Med 81(6): 5-10.

- Fleming R, Berkowitz B, Cheadle AD (2005) Increasing minority representation in the health professions. J School Nurs 21(1): 31–39.

- Cohen JJ, Gabriel BA, Terrell C (2002) The case for diversity in the health care workforce. Health Aff (Millwood) 21(5): 90–102.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 3132

- [From(publication date): 0-2021 - Nov 19, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 2393

- PDF downloads: 739