Disseminated BCG Disease in an Infant with Severe Combined Immunodeficiency

Received: 06-Oct-2016 / Accepted Date: 21-Oct-2016 / Published Date: 24-Oct-2016 DOI: 10.4172/2476-213X.1000112

Abstract

BCG (Bacillus Calmette Guerin) being a live attenuated vaccine may cause disseminated disease (BCGiosis) in patients with impaired immunity. Patients with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) having defect in both cellular and humoral immunity are predisposed to a host of live vaccine related complications, especially BCG.

We report a 6 month-old baby boy with fever for 5 months, generalized rash for 3 months, cough and cold for 1 month, poor feeding and weight loss over last 1 month. He had an uneventful perinatal period and received BCG at birth. Examination revealed mild pallor, generalized erythematous papular rash with central crusting and splenohepatomegaly. Skin biopsy and culture confirmed BCG infection while computed tomography of abdomen and skeletal survey showed disseminated involvement. Immunological investigations were suggestive of an underlying SCID. The infant showed improvement with antitubercular therapy combined with intravenous immunoglobulin and other supportive measures.

The case highlights the possible risk of such rare yet lethal complication of BCG especially at places where it is given routinely at birth or in the neonatal period and also emphasizes the need for neonatal screening for SCID in such regions.

Keywords: Primary immunodeficiency; Adverse event following immunization; Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; Neonatal screening

97819Introduction

Bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG) vaccine, made from an attenuated strain of Mycobacterium bovis , is administered routinely in the neonatal period in TB endemic countries including India, as a part of the Universal Immunization schedule. Having only local complications in general, BCG is associated with lethal disseminated disease in those with immunodeficiency [1,2]. Several primary immunodeficiency syndromes have been associated with disseminated BCG disease (BCGiosis), such as Mendelian susceptibility to Mycobacterial disease (MSMD), hyper-IgM syndrome, Di George syndrome, chronic granulomatous disease, Severe combined Immunodeficiency (SCID), IL (Interleukin)-12/23 receptor β1 chain deficiency, IL-12p40 deficiency, STAT1 (Signal transducer and activator of transcription 1) deficiency and NEMO (Nuclear factor kappa-beta essential modulator) deficiency [2-4]. SCID is arguably the most severe and lethal inherited primary immunodeficiency with a prevalence of approximately 1 in 50,000 live births. It is aptly called as a pediatric emergency as it invariably leads to fatality in infancy without early aggressive therapy and Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) or other specific therapy [5]. SCID is probably the commonest primary immunodeficiency associated with BCGiosis, though there is no such definitive data as most of the cases described in literature are in the form of reports and series.

We present an infant with SCID and BCGiosis. Our case describes the very rare yet possible risk of such a devastating complication of BCG, especially important for countries where it is given routinely; it also emphasizes the need for screening of new-borns for SCID in similar regions.

Case Report

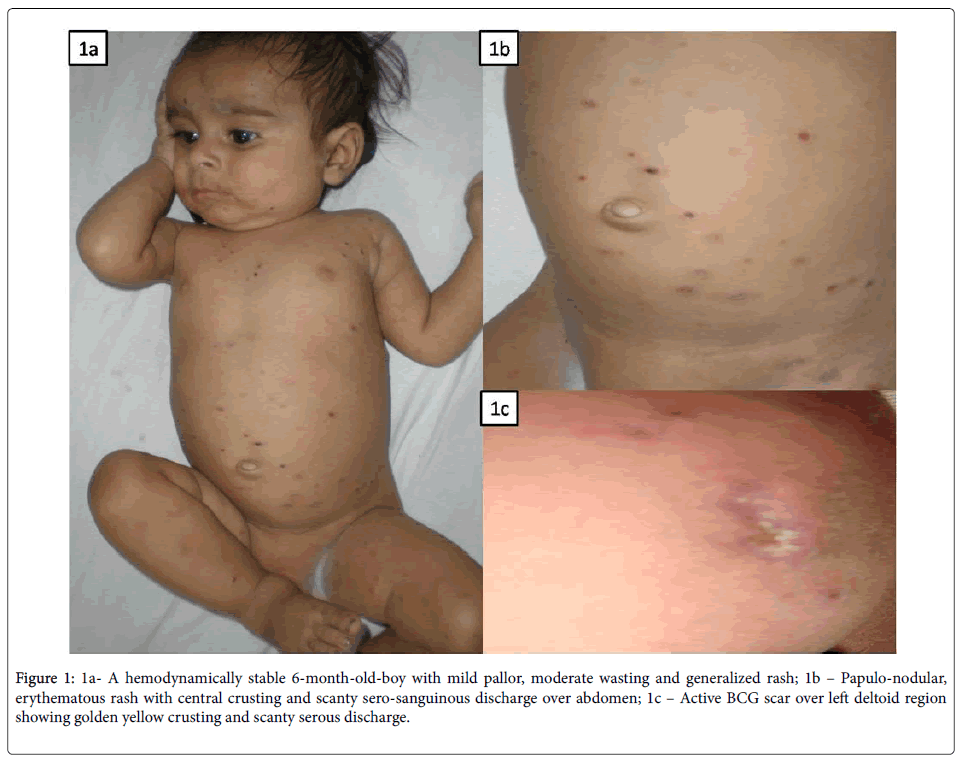

A-6 month-old baby boy was admitted with complaints of fever for 5 months, generalized rash involving palms and soles for 3 months, cough and cold for 1 month, poor feeding and weight loss over last 1 month. He received multiple courses of oral antibiotics with no response. There was no history of vesico-bullous lesion, mucosal involvement, itching or similar lesions in any other family members. There was also no history of contact with TB, ear discharge, seborrhea or blood component therapy. He was a product of nonconsanguineous marriage, born to a primigravida at term gestation by normal vaginal delivery with a birth weight of 3.35 kg. There was no history of chronic cough or infertility in the mother before conception and there was no antenatal history of fever with/ without rash or genital ulcers. There were no perinatal concerns and he remained apparently asymptomatic and well thriving on exclusive breastfeeding till 2 months of age. He received BCG and OPV (oral polio vaccine) at birth and was vaccinated till 10 weeks of age as per the National immunization schedule. On examination, he had stable vital parameters with mild pallor but no icterus or lymphadenopathy. Anthropometric parameters were suggestive of moderate wasting. There were erythematous papules all over the body with central crusting and scanty sero-sanguinous discharge (Figures 1a and 1b). The BCG site was still active with a crusted lesion and scanty serous discharge (Figure 1c).

Figure 1: 1a- A hemodynamically stable 6-month-old-boy with mild pallor, moderate wasting and generalized rash; 1b – Papulo-nodular, erythematous rash with central crusting and scanty sero-sanguinous discharge over abdomen; 1c – Active BCG scar over left deltoid region showing golden yellow crusting and scanty serous discharge.

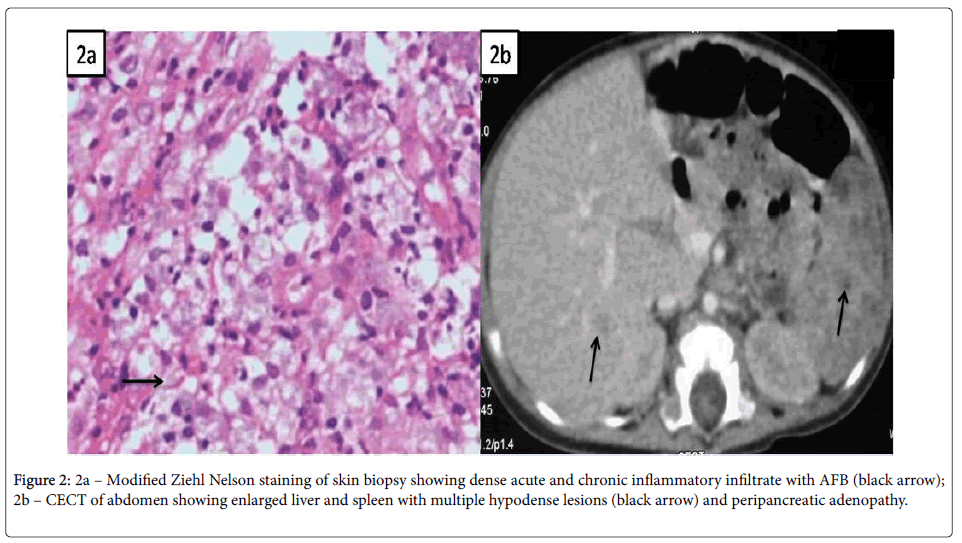

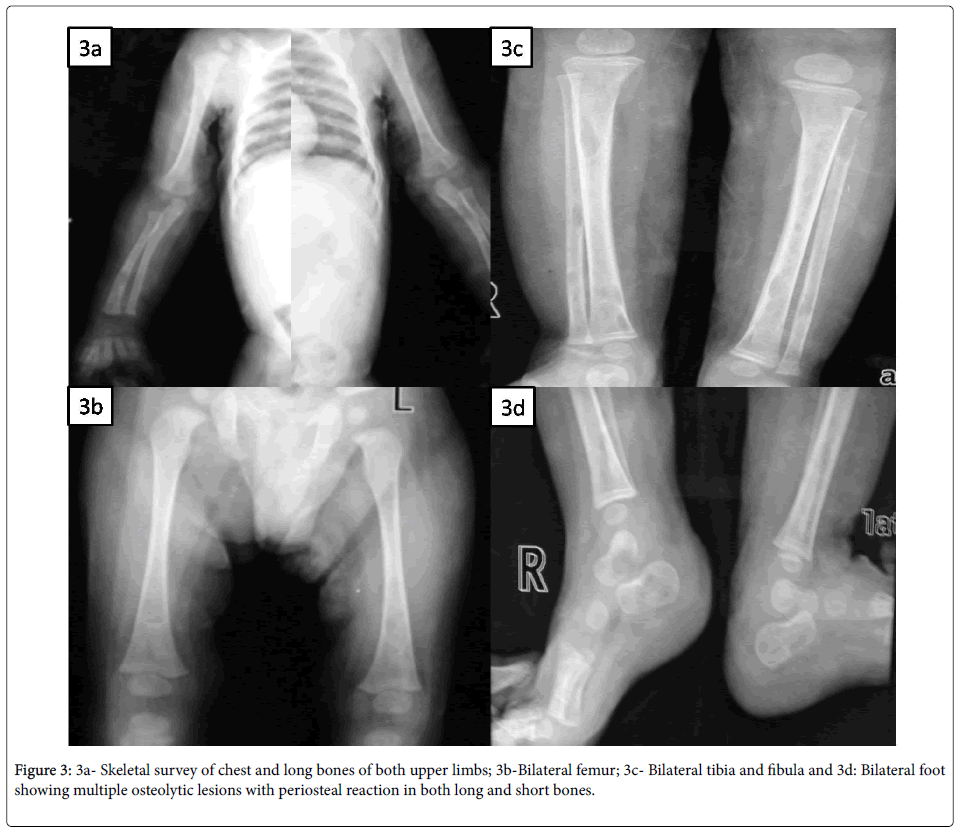

Systemic examination was remarkable with spleno-hepatomegaly but other systems were essentially normal. Initial investigations were suggestive of microcytic, hypochromic anemia, while rest was noncontributory (Table 1). So, skin biopsy was done from the lesions and it revealed irregular acanthosis and papillomatosis; dermis showing dense acute and chronic inflammatory infiltrate with collection of foamy histiocytes spilling into the subcutaneous tissue and modified Ziehl Nelson stain for AFB was positive (Figure 2a). MGIT (Mycobacterium growth indicator tube) culture of skin biopsy grew Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Skeletal survey showed multiple lytic lesion involving both long and short bones without sclerosis (Figure 3).

| Investigation | Result | Investigation | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (gm/dl) | 7.9 | Serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT) (U/L) | 36 |

| Total leukocyte count (/mm3) | 9600 | Serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase (SGPT) (U/L) | 33 |

| Differential leukocyte count | Neutrophil 76%, Lymphocyte 19%, Monocyte 4%, Eosinophil 1% | Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 312 |

| Platelet count | 2.9 lakh/mm3 | Calcium (mg/dl) | 8.9 |

| Peripheral smear | Microcytic, hypochromic red blood cells with marked aniso-poikilocytosis; no abnormal cells/ blasts | Phosphate (mg/dl) | 4.6 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 141 | Blood culture | Sterile |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 5 | Mantoux test | 0 mm |

| Urea (mg/dl) | 28 | VDRL (Venereal Disease Research Laboratory) | Negative |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.3 | TPHA (Treponema pallidum haemagglutination) test of mother | Negative |

| Total bilirubin/ conjugated (gm/dl) | 0.5/ 0.1 | HIV ELISA of mother | Negative |

| Total protein (gm/dl) | 5.9 | Chest x-ray | Normal |

| Albumin (gm/dl) | 3.5 | Gastric aspirate for acid fast bacilli | Negative |

Table 1: Initial investigations of the child.

Contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of abdomen showed enlarged liver and spleen with multiple hypodence lesions and peripancreatic adenopathy (Figure 2b); while, CT brain and chest were normal. He was started on category 1 four drug antitubercular therapy along with nutritional rehabilitation and other supportive measures. But his fever persisted with worsening of general condition. Further immunological investigations carried out were suggestive of Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) (Table 2). Mutational analysis could not be done due to unavailability of facilities for genetic studies. He was given intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and was also started on antifungal (Fluconazole) and antibacterial (Cotrimoxazole) prophylaxis. In the meantime species typing of the isolated mycobacterium revealed Mycobacterium bovis confirming the diagnosis of disseminated BCG disease. The antitubercular therapy was modified to replace Pyrizinamide with Levofloxacin and addition of Amikacin. Gradually the child improved and bone marrow transplantation was planned. On follow up till 2 months after discharge, he remained afebrile, gained weight and most of the skin lesions also healed; but he was lost to follow up after that.

| Investigation | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Immunoglobulin G (mg/dl) | 112 | 217-964 |

| Immunoglobulin A (mg/dl) | 7 | 34-126 |

| Immunoglobulin M (mg/dl) | 3 | Nov-90 |

| Absolute lymphocyte count (/mm3) | 1188 | 5300-6700 |

| CD3+ T lymphocyte (/mm3) | 1 | 3400-4600 |

| CD4+ T lymphocytes (/mm3) | 0 | 2600-3500 |

| CD8+ T lymphocytes (/mm3) | 1 | 390-2500 |

| CD19+ T lymphocytes (/mm3) | 17 | Nov-45 |

| CD16/56+ T lymphocytes (/mm3) | 2 | Nov-24 |

Table 2: Immunological investigations of the child.

Discussion

Our patient had persistent fever, weight loss, anemia, hepatosplenomegaly, skin rash and multiple osteolytic lesions. Initial possibilities considered were congenital syphilis, congenital TB/ acquired disseminated TB, Langerhan’s cell histiocytosis (LCH), metastatic neuroblastoma and hematological malignancies. Noninvasive investigations being non-contributory, skin biopsy and subsequent culture results confirmed the diagnosis of mycobacterial infection. Prolonged history, atypical clinical features and radiological involvement coupled with poor response to appropriate therapy prompted us to look for an underlying immunodeficiency and established the diagnosis of SCID even before the final diagnosis of BCGiosis was made.

Though there is no established definition, our patient fulfilled the criteria for a ‘definitive’ case of disseminated BCG infection as per the proposed diagnostic criteria [2,6]. Our child had most of the frequently described manifestations of BCGiosis, i.e. fever, weight loss, anemia, skin rash and organomegaly but lymphadenopathy was conspicuously absent [2,7]. Skin manifestations have been an interesting mode of presentation in BCGiosis with a wide range of lesions being described ranging from maculo-papules, subcutaneous nodules and ulcers [2,6,7]. Our case had lesions similar to that of LCH and skin biopsy came to the aid. Indeed, skin biopsy has been shown to be a critical investigation in diagnosis of BCGiosis and may have role in prognostication as well [8].

In a review of adverse events following immunization (AEFI) in cases of primary immunodeficiency [9] patients with SCID and CGD had the greatest percentage of serious AEFI with BCG being the most commonly incriminated vaccine. Complications of BCG including BCGiosis have been described with all the genetic forms of SCID with no identifiable difference between various types [4]. In a recent review [10] of 349 BCG-vaccinated patients with SCID from 17 countries 51% of patients had BCG-associated complications, 34% disseminated and 17% localized. BCG associated complications and death were more common in children receiving early (<1 month) vaccination. Interestingly, BCG-associated complications were reported in only 2 of 78 patients who received antitubercular therapy before symptom onset with no deaths caused by BCG-associated complications. In contrast, 46 BCG-associated deaths were reported among 160 patients treated with antitubercular therapy for a symptomatic BCG infection. Even after HSCT, immune reconstitution syndrome (IRS) remains an important cause of morbidity and mortality in this group of SCID patients.

Data from Brazil, a country with high burden of TB, where routine BCG immunization is administered in neonatal period reveals that around 86% of children received BCG before their SCID diagnosis and 41% developed BCGiosis; half of the patients died with BCGiosis being the predominant cause [11].

Conclusion

In countries with routine BCG administration in infancy BCGiosis is an important mode of presentation of primary immunodeficiencies, especially SCID. To avoid delayed diagnosis of SCID and the organ damage secondary to BCGiosis, neonatal screening to identify lymphopenia should be considered. On the other hand patients, who already received BCG before diagnosis of SCID, may be started on antitubercular therapy along with standard management guidelines [5,10] even before symptom onset.

Authorship

All the authors have contributed substantially in intellectual content, conception, manuscript writing, and approve the final manuscript. Anirban Mandal being the corresponding author will act as a guarantor for other authors.

Conflicts of Interest

None

Funding

None

References

- Lott A, Wasz-Höckert O, Poisson N, Dumitrescu N, Verron M, et al. (1984) BCG complication: Estimates of the risk among vaccinated subjects and statistical analysis of their characteristics. Adv Tuberc Res 21: 107-93.

- Talbot EA, Perkins MD, Silva SF, Frothingham R (1997) Disseminated bacilli Calmette-Guerin disease after vaccination: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis 24: 1139-1146.

- Sadeghi-Shanbestari M, Ansarin K, Maljaei SH, Rafeey M, Pezeshki Z, et al. (2009) Immunologic aspects of patients with disseminated bacille Calmette-Guerin disease in north-west of Iran. Ital J Pediatr 35: 42-46.

- Norouzi S, Aghamohammadi A, Mamishi S, Rosenzweig SD, Rezaei N (2012) Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) complications associated with primary immunodeficiency diseases. J Infect Dis 64: 543-544.

- Madkaikar M, Aluri J, Gupta S (2016) Guidelines for Screening, Early Diagnosis and Management of Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID) in India. Indian J Pediatr 83: 455-462.

- Bernatowska EA, Wolska-Kusnierz B Pac, M Kurenko-Deptuch, Zwolska Z, Casanova JL, et al. (2007) Disseminated bacillus Calmette-Guérin infection and immunodeficiency. Emerg Infect Dis 13: 799-801.

- Shahmohammadi S, Saffar MJ, Rezai MS (2014) BCG-osis after BCG vaccination in immunocompromised children: Case series and review. J Pediatr Rev 2: 47-54.

- Gantzer A, Neven B, Picard C, Brousse N, Lortholary O, et al. (2013) Severe cutaneous bacillus Calmette-Guérin infection in immunocompromised children: the relevance of skin biopsy. J Cutan Pathol 40: 30-37.

- Sarmiento JD, Villada F, Orrego JC, Franco JL, Trujillo-Vargas CM (2016) Adverse events following immunization in patients with primary immunodeficiencies. Vaccine 34: 1611-1616.

- Mazzucchelli JT, Bonfim C, Castro GG, Condino-Neto AA, Costa NM, et al. (2014) Severe combined immunodeficiency in Brazil: management, prognosis, and BCG-associated complication. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 24: 184-191.

- Marciano BE, Huang CY, Joshi G, Rezaei N, Carvalho BC, et al. (2014) ‘BCG vaccination in patients with severe combined immunodeficiency: complications, risks, and vaccination policies. J Allergy Clin Immunol 133: 1134-1141.

Citation: Mandal A, Singh A, Sahi PK, Rishi B (2016) Disseminated BCG Disease in an Infant with Severe Combined Immunodeficiency. J Clin Infect Dis Pract 1:112. DOI: 10.4172/2476-213X.1000112

Copyright: © 2016 Mandal A et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 16838

- [From(publication date): 12-2016 - Apr 07, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 15813

- PDF downloads: 1025