Research Article Open Access

Different Biologic Grafts for Diaphragmatic Crura Reinforcement during Laparoscopic Repair of Large Hiatal Hernia: A 6-Year Single Surgeon Experience

Reznichenko AA*

Department of Surgery, Tulare Regional Medical Center, CA 93274, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Reznichenko AA, M.D, Ph.D

Department of Surgery

Tulare Regional Medical Center, CA 93274, USA

Tel: +1 559-688-0821

E-mail: areznik9@yahoo.com

Received Dtae: October 12, 2015; Accepted Date: November 23, 2015; Published Date: December 10, 2015

Citation: Reznichenko AA (2015) Different Biologic Grafts for Diaphragmatic Crura Reinforcement during Laparoscopic Repair of Large Hiatal Hernia: A 6-Year Single Surgeon Experience. J Med Imp Surg 1:101.

Copyright: © 2015 Reznichenko AA. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Medical Implants & Surgery

Abstract

Background: Large hiatal hernias represent a challenge for surgeons. Biologic grafts are currently popular for the strengthening of crural closure during laparoscopic repair. This study is a retrospective review of crural reinforcement in laparoscopic repair of large hiatal hernias using various biologic grafts performed by a single surgeon in a rural community hospital.

Methods: Eleven (n=11) patients underwent laparoscopic repair of large hiatal hernia in a rural community hospital by a single surgeon from 2009 to 2015. Standard laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair was performed. Different biologic grafts were used for crural reinforcement, including “AlloMax”, “Permacol”, and “Acell MatriStem”. Perioperative data and outcomes of surgery were evaluated.

Results: There were six females and five males, mean age was 55.4 years, mean BMI was 32.5. Eight patients had type III hiatal hernia, two patients had type IV, and one patient had type II. Mean operative time was 244.6 minutes, and mean length of stay was 3.3 days. Mean size of herniated stomach in the chest was 62%. Mean sizes of the hiatal defect was 7.7 cm × 6.4 cm. One perioperative complication (9%) included bleeding from left gastric artery. Early complications included shortness of breath (18%), parapneumonic effusion (18%), and early dysphagia (18%). Late complications included persistent gastro esophageal reflux (9%), gastroparesis (9%), and persistent dysphagia (9%). Radiological recurrence was 18% and clinical recurrence was 9% at mean follow up of 15 months.

Conclusions: Laparoscopic repair of large hiatal hernia could be safely performed in rural community hospitals. The choice of the biologic graft, if one is used, should be at the discretion of the surgeon. The cost and availability of the biologic graft is important in decision making.

Keywords

Laparoscopy; Large hiatal hernia; Hiatal hernia repair; Reinforcement of crural closure; Biologic mesh

Introduction

Minimally invasive approach in the repair of hiatal hernias became a standard of care during the last two decades. Laparoscopy offers faster recovery, shorter hospital stay and less morbidity than traditional laparotomy [1,2]. Several studies have shown higher recurrence rates after a suture-based repair of hiatal hernias [3-5]. A “tension-free” repair with prosthetic mesh allowed to decreased recurrence [6], but the use of synthetic materials produced potentially serious problems, such as erosion and dysphagia [7-10]. Multiple reports showed reduction in short-term recurrence rate after hiatal hernia repair with biologic grafts [11-15]. However, the improvement in hiatal hernia recurrence decreased at long-term follow-up [16].

Biologic grafts used in hiatal hernia repairs are safe, and the incidence of mesh related complications are low [11,12,15-19]. This is a study of various biologic grafts used for diaphragmatic crura reinforcement during laparoscopic repair of large hiatal hernias performed by a single surgeon in a rural community hospital.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective review was conducted of 11 patients who underwent laparoscopic repair of large hiatal hernia in a rural community hospital by a single general surgeon from 2009 to 2015. Only those hernias at least 6 cm in size (distance between right and left crus) and with 40% or more of the stomach herniated into the chest were included. This was determined by preoperative endoscopy, barium swallow study, computer tomography, and intra operatively. Patient demographics, preoperative symptoms, BMI, type and size of the hernia, operative times, length of stay, intra operative and postoperative complications were all evaluated. Follow-up data was examined to identify postoperative symptoms and improvement of quality of life, the presence of clinical or radiological recurrences, and mesh related complications.

Surgical technique

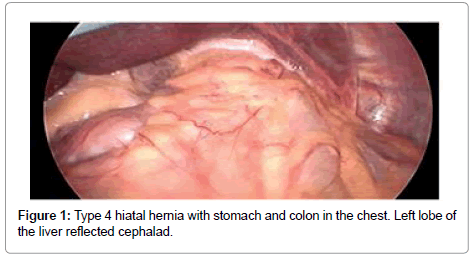

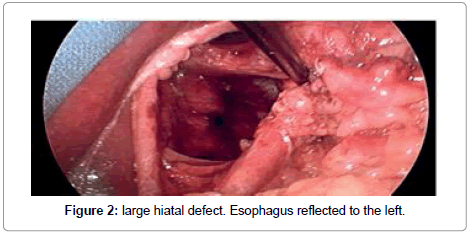

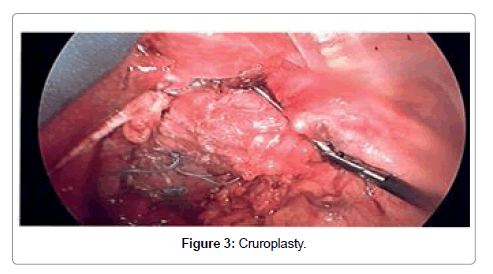

A standardized laparoscopic technique was utilized for all hiatal hernia repairs. There were no conversions to open procedure. All hernias were primary. There were no revisional surgeries. Five laparoscopic ports were used with the exception of one patient, who had BMI of 46. The position of the ports were as follows: umbilical (5 or 10 mm) as an optical port, right upper quadrant (10 mm) for retraction of the left lobe of the liver, three working ports (5 mm each) in the epigastric area, in the left upper quadrant and in the left mesogastrium. The left lobe of the liver was reflected cephalad with a Covidien 12 mm Endo Paddle Retract™ (Figure 1). Five or ten mm 30-degree laparoscope was utilized. The diaphragmatic crura was opened from left to right. The short gastric vessels and the posterior gastric vessels to the base of the left crus were divided selectively, depending on the intraoperative findings. The hernia sac was dissected initially from the hiatus, followed by complete circumferential dissection from the mediastinal structures. Mediastinal lipomas were present in four patients. These were dissected and excised. The size of the herniation of the stomach into the chest was estimated based on both preoperative studies, and intra operatively, after stomach was returned back to the intra abdominal cavity. Esophagus was dissected in the mediastinum as high as possible. Both vagus nerves were identified and preserved. Intra abdominal esophageal length of minimum 2.5 cm was accomplished with extensive mediastinal dissection; there was no need to perform vagotomy or Collis gastroplasty for the lengthening of the esophagus in this study. The size of the hernia was measured as a distance between right and left crus, and anterior to posterior distance between hiatal apex and posterior decussation of the right and left crus (Figure 2). Posterior crural closure was performed with interrupted Ethibond endoknot sutures SKU EX10G (Ethicon Inc.) (Figure 3). Additional anterior sutures were placed selectively on the crura depending on intra operative situation.

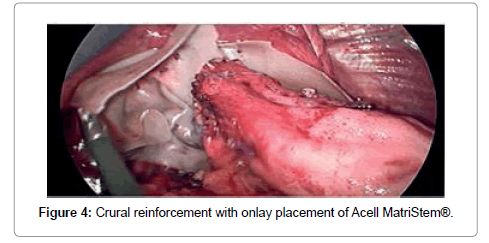

The biologic graft for crural reinforcement was chosen based on the availability and the cost of the product. Three different types of graft were used, including acellular human dermal collagen (AlloMax™) in six patients, cellular porcine dermal implant (Permacol™) in one patient and porcine urinary bladder matrix (Acell MatriStem®) in four patients. The size of the graft was either 10 cm x 15 cm or 7 cm x 10 cm, depending on the size of the defect. After the graft was hydrated for 30 minutes, it was fashioned into “U” shape (with or without creation of a keyhole) and placed as an onlay patch posterior to the esophagus over the crural closure. Graft was secured to the diaphragm with hernia stapler (Figure 4). ENDOPATH® EMS 10 mm Endoscopic stapler (Ethicon Inc.) was used for securing of AlloMax™ graft, ProTack Autosuture 5mm stapler (Covidien Ltd) for Permacol™, and SECURESTRAP® Absorbable Fixation Device (Ethicon Inc.) for Acell Matri Stem®. Fundoplication performed in ten out of eleven patients, using anterior Dor technique in eight patients, Nissen in one patient, and Toupet in one patient.

Results

Eleven patients underwent laparoscopic repair of large hiatal hernias with the reinforcement of the crural closure with biologic graft. There were six females and five males, mean age was 55.4 years (± 8.7), mean BMI was 32.5 (± 7.5). Chest pain was the most common symptom (91%), followed by dysphagia (82%), epigastric abdominal pain and heartburn (64% each), shortness of breath (55%), nausea and vomiting (4%), hematemesis (2%) and weight loss (1%) (Table 1). Preoperative evaluation included esophagogastro duodenoscopy in eight patients, computer tomography in all patients and upper gastrointestinal study in nine patients. Mean operative time was 244.6 minutes (± 71.7), and mean length of stay was 3.3 days (± 1.8). Six patients had the reinforcement of the crura with AlloMax™, one patient with Permacol™, and four patients with Acell MatriStem®. In all cases right and left crus were approximated. Three patients were operated under the urgent settings, with suspected diagnosis of gastric volvulus, based on clinical presentation and radiological findings. There was no evidence of acute gastric ischemia intraoperatively. The average size of herniated stomach in the chest was 62% (± 22.7), with entire stomach herniated inside the chest in two patients. Eight patients had type III hiatal hernia, two patients had type IV, and one patient had type II. Two patients with type IV hiatal hernia had colon together with stomach in the chest (Figure 5). Secondary procedure was performed in three patients along with hiatal hernia repair, including laparoscopic cholecystectomy in two patients, and umbilical hernia repair in one patient. Mean sizes of the hiatal defect was 7.7 cm (right to left) (± 1.1), and 6.4 cm (anterior to posterior) (± 0.8). Only one perioperative complication (9%) was encountered and included bleeding from left gastric artery in a morbidly obese patient (BMI 46) with EBL of 500 ml. Average intra operative blood loss was 65 ml (±145.4) (Table 2).

| Patient (n) | Gender | BMI* | Age | SYMPTOMS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epigastric pain | Chest pain | SOB ** | Dysp-hagia | Acid reflux | Nausea/ vomiting | Hemat-emesis | Weight loss | ||||

| 1 | M | 46 | 52 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | no |

| 2 | F | 37 | 57 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | no | no | no |

| 3 | F | 27 | 53 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | no | no | no |

| 4 | F | 36 | 67 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | yes | no | no |

| 5 | M | 22 | 68 | no | yes | no | no | yes | no | yes | no |

| 6 | F | 31 | 51 | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | no | yes |

| 7 | F | 34 | 42 | yes | yes | no | no | yes | no | no | no |

| 8 | M | 28 | 49 | no | no | yes | yes | no | no | no | no |

| 9 | M | 24 | 45 | no | yes | no | yes | no | no | no | no |

| 10 | M | 30 | 62 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | yes | no | no |

| 11 | F | 43 | 63 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | no |

| Total 11 |

M=5 F=6 | Mean 32.5(± 7.5) | Mean55.4 (±8.7) | % 64 |

% 91 |

% 55 |

% 82 |

% 64 |

% 4 |

% 2 |

% 1 |

*Body mass index, ** Shortness of breath

Table 1: Demographics and Symptoms.

| Patient (n) | Length of surgery (min) | Defect size (R to L)x(A x P), cm | Size (%) of stomach in the chest | Mesh type | Fundo-plication | EBL ** (ml) | Com-plica- tions | Media-stinal- lipoma | Secondary operation | Hermia type | LOS * (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 305 | 8 x 7 | 70 | Acell | Dor | 500 | bleeding | yes | no | 3 | 6 |

| 2 | 146 | 7 x 7 | 50 | Acell | Dor | 10 | no | no | no | 3 | 2 |

| 3 | 213 | 9 x 6 | 60 | Acell | no | 10 | no | no | no | 4 | 2 |

| 4 | 240 | 8 x 7 | 50 | Acell | Dor | 50 | no | no | no | 3 | 2 |

| 5 | 191 | 6 x 6 | 40 | Allomax | Nissen | 50 | no | no | UHR*** | 3 | 2 |

| 6 | 320 | 9 x 6 | 100 | Allomax | Dor | 10 | no | no | no | 4 | 4 |

| 7 | 207 | 8 x 6 | 40 | Allomax | Dor | 10 | no | yes | Lap chole | 2 | 6 |

| 8 | 370 | 8 x 5 | 80 | Allomax | Dor | 50 | no | yes | no | 3 | 4 |

| 9 | 171 | 7 x 6 | 40 | Allomax | Dor | 10 | no | no | no | 3 | 1 |

| 10 | 315 | 9 x 8 | 50 | Permacol | Dor | 10 | no | yes | no | 3 | 5 |

| 11 | 213 | 6 x 6 | 100 | Allomax | Toupet | 10 | no | no | Lap chole | 3 | 2 |

| Total 11 | Mean 244.6 (± 71.7) | Mean 7.7 (± 1.1) x 6.4 (± 0.8) | % 62 | 6 + 4 + 1 = 11 | 8 + 1 + 1 + 1 = 11 | Mean 65 (± 145.4) | % 9 | % 36 | % 27 | 8 + 2 + 1 = 11 | Mean 3.3 (± 1.8) |

*Estimated blood loss, ** Length of stay, ***Umbilical hernia repair

Table 2: Perioperative data.

Postoperatively all patients were kept on National Dysphagia Level II diet for 4 weeks, with subsequent slow transition to regular diet within 6 to 8 weeks. Clinical follow-up ranged from 3 to 40 months. All patients were evaluated with standard questionnaire; during the interviews they were asked about the existence and/or persistence of their symptoms. An objective score test, the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index (GIQLI), was also administered. All eleven patients noticed disappearance of epigastric pain, chest pain, nausea and vomiting, hematemesis and weight loss. Early symptoms and complications included shortness of breath in two patients (18%), parapneumonic effusion in two patients (18%), and early dysphagia in two patients (18%). These complications completely resolved in within 3 to 4 weeks postoperatively. One patient with parapneumonic effusion required one-time aspiration by interventional radiology.

Late complications included persistent gastroesophageal reflux in one patient (9%), gastroparesis in one patient (9%), and persistent dysphagia in one patient (9%). A patient with persistent gastroesophageal reflux during 6 month follow-up had no other symptoms, and was satisfied with surgery and quality of life. The severity of acid reflux after surgery decreased and the patient was successfully treated with proton pump inhibitors. Computer tomography was performed for other indications and showed a small recurrent paraesophageal hernia.

One patient experienced abdominal bloating and early satiety, and was diagnosed with gastroparesis. This patient had the most technically challenging and time consuming operation (among all eleven patients in this study) secondary to severe dense adhesions of large hernia sac to the mediastinal structures. Patient was treated successfully with dopamine-receptor antagonist, and showed no evidence of recurrence at the 24 month follow-up.

One patient with persistent dysphagia was diagnosed with recurrent hiatal hernia at 6 month follow-up. This patient underwent esophagogastroscopy, which showed stricture in the distal esophagus. Balloon dilatations of the stricture was performed with improvement, but not complete resolution of dysphagia.

Seven patients (64%) underwent radiological evaluation postoperatively within 6 to 24 month follow-up. Two patients (18%) underwent esophagogastroscopy. Among eleven patients in this study one had clinical recurrence (9%), and two had radiological recurrence (18%) (Table 3).

| Pati-ent (n) | SYMPTOMS AFTER SURGERY AND POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS | POSTOPERATIVE EVALUATION | F/U*** (months) | RECURRENCE | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOB | Early Dysphagia | Acid reflux | Persistent Dysphagia | Gastro-paresis | Para- pneumonic effusion | CT | EGD* | UGI ** | Clin- ical | Radiol-ogical | ||

| 1 | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | 3 | no | n/a |

| 2 | no | no | no | no | no | no | yes | no | no | 18 | no | no |

| 3 | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | yes | 12 | no | no |

| 4 | yes resolved | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | 12 | no | n/a |

| 5 | no | yes resolved | no | no | no | no | yes | no | no | 30 | no | no |

| 6 | yes resolved | no | no | no | no | yes aspirated | yes | no | no | 40 | no | no |

| 7 | no | no | yes | no | no | no | yes | no | no | 6 | no | yes |

| 8 | no | yes resolved | no | no | yes | yes resolved | yes | yes | yes | 24 | no | no |

| 9 | no | no | no | yes improved | no | no | no | yes (balloon dilatation) | yes | 6 | yes | yes |

| 10 | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | 6 | no | n/a |

| 11 | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | no | 6 | no | n/a |

| Total 11 | % 18 | % 18 | % 9 | % 9 | % 9 | % 18 | % 45 | % 18 | % 27 | Mean 15.3 (± 12) | % 9 | % 18 |

*Esophagogastroscopy, **Upper GI series, ***Follow-up

Table 3: Results.

Discussion

Laparoscopic approach became a standard of care for the repair of hiatal hernias because it offers faster recovery, shorter hospital stay, and less morbidity than traditional open approach [1,2]. Operative steps in the laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair include: reduction of the stomach from mediastinum, dissection of the hernia sac away from mediastinal structures, return of gastroesophageal junction to an infra diaphragmatic position ensuring an appropriate (at least 2-3-cm) intra abdominal length of the esophagus, primary crural closure, and fundoplication [2]. There is no consensus regarding fundoplication during repairs of large hiatal hernias [2,20,21]. Fundoplication was not performed on only one patient in this study; this patient with type IV hiatal hernia was presented with severe dysphagia, and did not have acid reflux. Patient has no clinical and/or radiological recurrence and no evidence of acid reflux during 12 months follow-up.

Esophageal lengthening procedures were not performed in this study. It was felt that high esophageal mobilization in the mediastinum was sufficient to achieve at least 2.5 cm of intra abdominal length of the esophagus. Mediastinal lipomas were encountered in four patients and were excised.

Controversy exists around the reinforcement of the diaphragmatic crura, as well as the type of the graft used, and the value of the graft in preventing recurrence, around short- and long-term complications, and the consequences of those complications compared with primary repair [17].

Higher recurrence rates were reported after suture-based laparoscopic repair of hiatal hernia [3-5]. Two prospective, randomized clinical trials have shown that “tension-free” laparoscopic hernia repair with prosthetic graft prevents recurrence [6,7]. However, using of synthetic materials for crural reinforcement produced potentially serious problems, such as erosion and dysphagia [7-10]. This lead to popularization of biological grafts.

After initial enthusiasm in reduction of short-term recurrence rates [11-15], the benefit of biologic grafts in the improving of hiatal hernia recurrence decreased at long-term follow-ups. A multicenter prospective, randomized trial [Oelschlager, et al] showed no significant difference in relevant symptoms or quality of life between patients undergoing primary laparoscopic hiatal hernia repair and small intestinal sub mucosa (SIS) buttressed repair. The recurrence rate after repair with biological graft approached 54% at median follow-up of 58 months [16]. We had 18% rate of radiological recurrence at mean follow-up of 15 months, however, only seven out of eleven patients had imaging studies postoperatively. Two patients failed to follow-up after 6 months, one patient refused to have an imaging study, and another patient had just recently underwent hiatal hernia repair. All of these patients were satisfied with operation and quality of life, and have not had a clinical recurrence of hiatal hernia.

The safety of biologic graft in hiatal hernia repairs was emphasized in several published series, and the incidence of graft related complications and side effects were low [11,12,15-19]. There were no graft related complications noticed throughout this study.

Despite the disappointingly high radiological recurrence rates in recent series [16,20,21-25], laparoscopic repair of hiatal hernias with biologic graft has shown an excellent long-term quality of life. There was a 9% rate of clinical recurrence in this study at 15 month followup. Persistent gastro esophageal reflux in one patient and gastropares is in another were managed conservatively with success. One patient with recurrent hernia and persistent dysphagia under went esophago gastroscopy which showed stricture in the distal esophagus. Balloon dilatation was performed with improvement, but not complete resolution of dysphagia.

Recent multicenter randomized controlled trial showed no difference in the outcome between primary repair, repair with synthetic mesh and repair with biologic graft. At the same time, the quality of life improved significantly after all types of hernia repair [26]. According to the most recent reviews, either mesh repair or primary repair may be the treatment of choice, based on the decision made by individual surgeons, and depending on their own recurrence and reoperation rates [17]. With regard to the choice of mesh, it should also be at the discretion of the surgeon based on his/her experience. The choice of the graft in this study was made based not only on the preference of the surgeon, but also on the availability and the cost of the product. It is important to emphasize that the cost became a significant important factor for the decision making due to current condition of the health care system, particularly in the settings of rural community hospitals. Three different types of biologic graft were used, including acellular human dermal collagen (AlloMax™) in six patients, cellular porcine dermal implant (Permacol™) in one patient and porcine urinary bladder matrix (Acell MatriStem®) in four patients.

AlloMax™ Surgical Graft (Bard Davol Inc.) is an acellular non-crosslinked human dermis allograft. Several studies have shown success in using AlloMax™ for breast reconstruction [27], ventral hernia repair [28], and hiatal hernia repair [19].

Permacol™ (Covidien Ltd.) is xenogeneic and composed of crosslinked porcine dermal collagen. Permacol™ was shown to be safe with relatively low rates of recurrence in repair of ventral and incisional hernias [29], and large complex abdominal wall hernias [30]. There were few reports of using Permacol™ in large diaphragmatic hernias [31-33].

Acell Matristem® (Acell Inc.) is an extracellular matrix scaffold composed of the decellularized epithelial basement membrane and lamina propria of the porcine urinary bladder. Acell Matristem® was successfully used in the treatment of difficult non healing radiated wounds [34] and complex pilonidal wounds [35]. One recent study has shown that the use of urinary bladder matrix may be helpful in decreasing the incidence of esophagojejunal anastomotic leak and/or stricture after total gastrectomy [36].

All biologic grafts in this study were hydrated for 30 minutes, fashioned into “U” shape, and placed as an onlay patch posterior to the esophagus over the crural closure. All products were easy to work with. Hernia staplers were used to secure the grafts to the diaphragm. A cell Matristem® graft was secured with absorbable tacks, which were less traumatic compared to permanent titanium tacks. A cell Matristem® graft had a little higher pliability. However, it should be emphasized, that this reflects only an individual surgeon opinion.

There were no differences between various types of grafts in this study with regard to operative time, length of stay and complications. Two of the recurrences occurred in patients with Allomax™ graft. However, this data is not sufficient enough to conclude that one product was superior to the other.

In conclusion, laparoscopic repair of large hiatal hernias is a challenging and complex procedure. When all the principles are followed, this operation could be effectively and safely performed in rural hospitals. The choice of the repair and the choice of mesh, if the one is used, is up to the individual surgeon. The cost and availability of the biologic graft is important in decision making.

Acknowledgements

Philip L. Leggett, M.D, F.A.C.S, Houston Northwest Medical Center, TX

References

- Athanasakis H, Tzortzinis A, Tsiaoussis J, Vassilakis JS, Xynos E (2001) Laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia. Endoscopy 33:590-594.

- Kohn GP, Price RR, DeMeester SR, Zehetner J, Muensterer OJ, et al. (2013)Guidelines for the management of hiatal hernia. SurgEndosc 27:4409-28.

- Hashemi M, Peters JH, DeMeester TR, Huprich JE, Quek M, et al. (2000) Laparoscopic repair of large type III hiatal hernia: objective follow-up reveals high recurrence rate. J Am Col lSurg 190:553-60.

- Diaz S, Brunt LM, Klingensmith ME, Frisella PM, Soper NJ (2003) Laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair, a challenging operation: medium-term outcome of 116 patients. J GastrointestSurg 7:59-66.

- Mattar SG, Bowers SP, Galloway KD, Hunter JG, Smith CD (2002) Long-term outcome of laparoscopic repair of paraesophageal hernia. SurgEndosc 16:745-9.

- Frantzides CT, Madan AK, Carlson MA, Stavropoulos GP (2002) A prospective, randomized trial of laparoscopic polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) patch repair vs simple cruroplasty for large hiatal hernia. Arch Surg 137:649-52.

- Granderath FA, Kamolz T, Schweiger UM, Pointner R (2006) Impact of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with prosthetic hiatal closure on esophageal body motility: Results of a prospective randomized trial. Arch Surg 141:625-32.

- Hazebroek EJ, Leibman S, Smith GS (2009) Erosion of a composite PTFE/ePTFE mesh after hiatal hernia repair.SurgLaparoscEndoscPercutan Tech 19:175-7.

- Fenton-Lee D, Tsang C(2010) A series of complications after paraesophageal hernia repair with the use of Timesh: a case report. SurgLaparoscEndoscPercutan Tech 20: e95-6.

- Arroyo Q, Argüelles-Arias F, Jimenez-Saenz M, Herrerias-Gutierrez JM, Pellicer Bautista F, et al. (2011) Dysphagia caused by migrated mesh after paraesophageal hernia repair. Endoscopy.

- Oelschlager BK, Pellegrini CA, Hunter J, Soper N, Brunt M, et al. (2006) Biologic prosthesis reduces recurrence after laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. Ann Surg 244:481-90.

- Diaz DF, Roth JS (2011) Laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair with acellulardermal matrix cruroplasty. JSLS 15:355-60.

- Lee E, Frisella MM, Matthews BD, Brunt LM (2007) Evaluation of acellular human dermis reinforcement of the crural closure in patients with difficult hiatal hernias. SurgEndosc 21:641-5.

- Wisbach G, Peterson T, Thoman D (2006)Early results of the use of acellular dermal allograft in type III paraesophageal hernia repair. JSLS 10:184-7.

- Lee YK, James E, Bochkarev V, Vitamvas M, Oleynikov D (2008) Long-term outcome of cruroplasty reinforcement with human acellular dermal matrix in large paraesophageal hiatal hernia. J GastrointestSurg 12:811-5.

- Oelschlager BK, Pellegrini CA, Hunter JG, Brunt ML, Soper NJ, et al. (2011) Biologic prosthesis to prevent recurrence after laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair: long-term follow-up from a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. J Am CollSurg 213461-8

- Obeid NM, Velanovich V (2013)The choice of primary repair or mesh repair for paraesophageal hernia: a decision analysis based on utility scores. Ann Surg 257:655-64.

- Wassenaar EB, Mier F, Sinan H, Petersen RP, Martin AV, (2012) The safety of biologic mesh for laparoscopic repair of large, complicated hiatal hernia. SurgEndosc 26:1390-6.

- Alicuben ET, Worrell SG, DeMeester SR (2014)Resorbable biosynthetic mesh for crural reinforcement during hiatal hernia repair. Am Surg 80:1030-3.

- Morris-Stiff G, Hassn A (2008) Laparoscopic paraoesophageal hernia repair: fundoplication is not usually indicated. Hernia12:299-302.

- Linke GR, Gehrig T, Hogg LV, Göhl A, Kenngott H, et al. (2014) Laparoscopic mesh-augmented hiatoplasty without fundoplication as a method to treat large hiatal hernias. Surg Today 44:820-6.

- Lidor AO, Steele KE, Stem M, Fleming RM, Schweitzer MA, et al. (2015) Long-term Quality of Life and Risk Factors for Recurrence after Laparoscopic Repair of Paraesophageal Hernia. JAMA Surg150:424-431.

- Targarona EM, Grisales S, Uyanik O, Balague C, Pernas JC, et al. (2013) Long-term outcome and quality of life after laparoscopic treatment of large paraesophageal hernia. World J Surg37:1878-82

- Jones R, Simorov A, Lomelin D, Tadaki C, et al. (2015) Long-term outcomes of radiologic recurrence after paraesophageal hernia repair with mesh. SurgEndosc 29:425-30.

- Oleynikov D (2015) Outcomes of Paraesophageal Hernia Repair. JAMA Surg150:431-432.

- Koetje JH, Irvine T, Thompson SK, Devitt PG, Woods SD, et al. (2015) Quality of Life Following Repair of Large Hiatal Hernia is improved but not influenced by Use of Mesh: Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. World J Surg 39:1465-73.

- Farias-Eisner GT, Small K,Swistel A, Ozerdem U, Talmor M (2014) Immediate implant breast reconstruction with acellular dermal matrix for treatment of a large recurrent malignant phyllodes tumor. Aesthetic PlastSurg 38:373-8.

- Roth JS1, Brathwaite C, Hacker K, Fisher K, King J (2014) Complex ventral hernia repair with humanacellular dermal matrix.Hernia 19: 247-52.

- Chand B, Indeck M, Needleman B, Finnegan M, Van Sickle KR, et al. (2014) A retrospective study evaluating the use of Permacol™ surgical implant in incisional and ventral hernia repair. Int J Surg 12: 296-303.

- Satterwhite TS, Miri S, Chung C, Spain DA, Lorenz HP, et al. (2012)Abdominal wall reconstruction with dual layer cross-linked porcine dermal xenograft: the "Pork Sandwich" herniorraphy. J PlastReconstrAesthetSurg 65:333-341.

- Gooch B, Smart N, Wajed S (2012) Transthoracic repair of an incarcerated diaphragmatic hernia using hexamethylenediisocyanate cross-linked porcine dermal collagen (Permacol). Gen ThoracCardiovascSurg 60:145-148.

- Lingohr P, Galetin T, Vestweber B, Matthaei H, Kalff JC, et al. (2014) Conventional mesh repair of a giant iatrogenic bilateral diaphragmatic hernia with an enterothorax. Int Med Case Rep J 7:23-25.

- Mitchell IC, Garcia NM, Barber R, Ahmad N, Hicks BA, et al. (2008)Permacol: a potential biologic patch alternative in congenital diaphragmatic hernia repair. J PediatrSurg 43:2161-2164.

- Rommer EA, Peric M, Wong A (2013) Urinary bladder matrix for the treatment of recalcitrant nonhealing radiation wounds. Adv Skin Wound Care26: 450-455.

- Sasse KC, Brandt J, Lim DC, Ackerman E (2013) Accelerated healing of complex open pilonidal wounds using MatriStem extracellular matrix xenograft: nine cases. J Surg Case Rep15.

- Afaneh C, Abelson J, Schattner M, JanjigianYY, Ilson D, et al. (2015) Esophageal reinforcement with an extracellular scaffold during total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Ann SurgOncol22:1252-1257.

Relevant Topics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 12255

- [From(publication date):

May-2016 - Nov 21, 2024] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 11540

- PDF downloads : 715