Research Article Open Access

Diagnostic Efficacy of Gingival Crevicular Blood for Assessment of Blood Glucose Levels in Dental Office: A cross Sectional Study

Deepa Jatti Patil* and Dhanyashri Kamalakkannan

Department of Oral Medicine, Diagnosis and Radiology, Swami Devi Dayal Dental College, Golpur, Panchkula, Haryana

- *Corresponding Author:

- Deepa.Jatti Patil

C/o Wing commander Bipin Patil

1214 A, sector 31B, Chandigarh

Tel: 07696263934

E-mail: iafdeepa@gmail.com

Received Date: August 12, 2014; Accepted Date: October 10, 2014; Published Date: October 13, 2014

Citation: Patil DP, Kamalakkannan D (2014) Diagnostic Efficacy of Gingival Crevicular Blood for Assessment of Blood Glucose Levels in Dental Office: A cross Sectional Study. J Oral Hyg Health 2:166. doi: 10.4172/2332-0702.1000166

Copyright: © 2014 Patil DP, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Oral Hygiene & Health

Abstract

Objectives: The gingival crevicular blood (GCB) obtained during routine periodontal probing may be a source for blood glucose measurements. The aim of this study was to compare gingival crevicular blood and fingerstick blood glucose measurements using a glucometer against the conventional laboratory methods.

Materials and Methods: The study group comprised of three groups. In the first group 30 patients with periodontitis and positive bleeding on probing were chosen. Blood samples of two sites intraorally were analyzed using a glucose self-monitoring device. The second and third group comprised of 50 diabetic and 50 non-diabetic patients. After testing fasting plasma glucose (FPG), fasting glucose levels in gingival crevicular blood (GCBG), and fasting capillary fingerstick blood (CFBG) samples were analyzed using same device.

Results: Significant correlation (r= 0.93, p<0.001) was found between gingival crevicular blood glucose levels and capillary finger stick blood glucose levels. Considerable correlation (r=0.75, p<0.001) was found between levels of fasting gingival crevicular blood glucose and fasting blood glucose both in diabetic patients and the normal population.

Conclusion: It is evident that the blood obtained during routine periodontal probing can be used for estimation of blood glucose levels. GCB can be used as a marker for blood glucose estimation using glucometer. The technique described is safe, easy to perform and helps to increase the frequency of diabetes screening in dental office.

Keywords

Diabetes mellitus; Periodontitis; Gingival crevicular blood; Glucometer; Fasting blood glucose

Introduction

Emerging trends have placed oral physicians at the forefront in diagnosing Diabetes mellitus (DM), control the illness and help those with prediabetes avoid full onset. It is undiagnosed in approximately half of the patients actually suffering from the disease [1]. DM is one of the most common, chronic diseases affecting mankind with considerable morbidity and mortality. It affects more than 120 million people worldwide, and it is estimated that it will affect 220 million by the year 2020 [1].

The literature provides consistent evidence of greater prevalence and severity of periodontal disease in, both type 1 and 2 diabetics. The presence of periodontitis increases the risk of worsening of glycemic control over time [2]. Periodontitis is considered to be one of the pathognomic oral warning signs and is designated as the sixth complication of DM [3]. Thorough periodontal therapy in these patients can help control the blood glucose levels and thereby preventing worsening of DM and onset of its complications.

In 1998, the World Health Organization [4] adopted the diagnostic parameters for diabetes established by the American Diabetes Association. Measuring the fasting blood glucose is considered to be the gold standard. These conventional laboratory methods employed to detect blood glucose are time consuming, invasive and require elaborative equipment [5]. The advent of blood glucose monitors allows the clinician to assess blood glucose at the chair side. In contrast to laboratory method, results are obtained instantaneously, which helps the clinician to decide if further confirmatory tests are required to diagnose diabetes. Recently there has been an increasing evidence of research carried out to use gingival crevicular blood in monitoring blood glucose levels [6-11]. The glucometer device may actually allow for painless testing of blood oozing from the gingival crevices of patients with periodontitis during routine periodontal examination and could be a simple and relatively inexpensive in-office screening device for any patient suspected to have diabetes. They can also be used to monitor blood glucose levels in known diabetics [5].

Development of a non-invasive method for measuring the blood glucose level is an urgent necessity, and putting such a method into practical use will reduce some of the physical and mental stress, that patient with diabetes endure [6].

The present study was conducted to evaluate the use of gingival crevicular blood as a marker for blood glucose estimation using glucometer against the conventional laboratory method. The aim of the study is to assess the reliability of gingival crevicular blood glucose as a diagnostic tool to assess blood glucose. The objectives of the study are:

• To compare the values of gingival crevicular blood glucose at two different sites inperiodontitis individuals.

• To compare crevicular and capillary blood glucose measurements in diabetic and nondiabetic individuals.

Materials and Methods

Patients reporting to the outpatient department of Oral medicine and Radiology, RVS Dental College & Arunachala Diabetic Centre aged between 20-70 years, were selected for the study after obtaining informed consent. The approval from the ethical committee of the institution was obtained regarding the study.

The patients were divided into 3 groups.

• Group A included 30 patients, 13 males and 17 females reporting to the outpatient department of Oral medicine and Radiology, RVS Dental College Patients with clinical signs of moderate to severe periodontitis were included in this group.

• Group B comprised of 50 diabetic patients with un-treated moderate to severe periodontitis, 20 females and 30 males selected from a list of diabetic patients, monitored regularly at Arunachala Diabetic Centre, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu.

• Group C included 50 non-diabetic patients with un-treated moderate to severe periodontitis, 32 females and 18 males randomly selected from individuals attending the Department of Oral medicine and Radiology, RVS Dental College and Hospital.

Inclusion criteria

• Patients 20-70 years of age.

• Patients diagnosed with moderate to severe periodontitis with and without Diabetes Mellitus

Exclusion criteria

• Any indication for antibiotic prophylaxis

• Any bleeding disorder

• Severe systemic diseases such as cardiovascular, renal, hepatic, immunologic, or haematological disorders.

• Any medication interfering with the coagulation system.

Clinical and laboratory analysis

Data was collected by the same qualified examiner trained through standardized procedures for making the required measurements. The device was calibrated prior to the study. 30 patients with periodontitis [Group A] were examined intraorally for visual signs of periodontal inflammation. Oral prophylaxis was performed to remove debris and the areas were isolated with cotton rolls to prevent saliva contamination and dried with compressed air. Areas with marked signs of inflammation were probed by a Williams probe, inserted into the gingival sulcus, as is commonly done during a periodontal examination. When the probe was removed, the gingival crevice was observed for bleeding. Probing was repeated until sufficient amount of blood appeared in the gingival crevice. Bleeding gingival sites were determined and two sites were chosen to assess the reliability of the glucometer. Two sites with profuse bleeding on probing with access for the glucose self monitoring device were chosen for testing fasting Gingival Crevicular Blood Glucose (GCBG).The two selected areas were analyzed using the glucometer (ACCU-CHEK Active, Roche Diagnostics, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions The glucometer was turned on by inserting the reagent strip into the test port. The top edge of the reagent strip of glucometerwas placed against the bleeding site. The blood was automatically drawn into reaction cell of the strip by capillary action, until the conformation window was full.

Fifty diabetic [Group B] and Fifty non-diabetic [Group C] patients with periodontitis were subjected to periodontal examination using the same method, and only one site with bleeding on probing was selected for testing fasting GCBG. Immediately after measuring fasting GCBG, capillary finger stick blood glucose (CFBG) was assessed using the same glucose self-monitoring device. The fingertip of fourth finger on the left hand was wiped with surgical spirit and was allowed to evaporate. The sample was drawn on the lateral surface of the fourth digit since it will have thinner epithelium and also it is a finger of lesser use. The hand was held down and the finger tip was gently massaged (but not squeezed) to obtain a round drop of blood. The first drop of blood was wiped away and the second drop was used. This was done to reduce the risk of an inaccurate result, should the sample contain excess tissue fluid or alcohol used to clean the finger. Patients with periodontitis also underwent routine laboratory measurement of fasting plasma glucose (FPG) levels. The fasting blood glucose levels of gingival crevicular blood (GCBG), capillary finger stick blood (CFBG) and the venous blood (FPG) of all patients were documented.

The glucose values obtained from gingival capillary blood, fingerstick blood, and venous blood from laboratory method were analyzed using SPSS statistical package. The correlation between blood glucose measurement pairs of patients with periodontitis was determined by calculating intra class correlation coefficient (ICC). In other two groups of the study, Pearson’s rank correlation was used. p value of <.001 was considered statistically significant.

Results

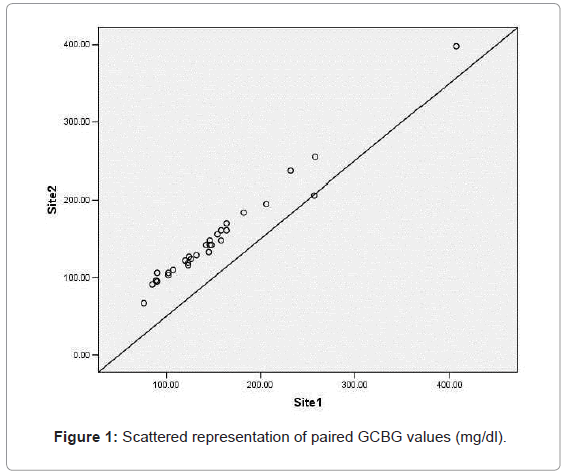

Patients with periodontitis [Group A] include 13 males and 17 females with a mean age of 51.46 ± 12.20 years old. The paired GCBG samples of periodontitis patients revealed an intra class correlation coefficient of 0.98 (p=0.001) (Figure 1).

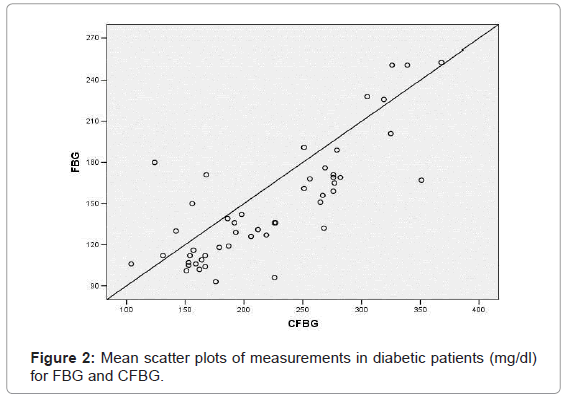

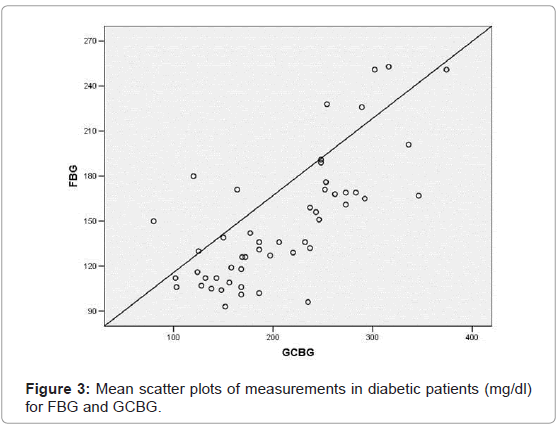

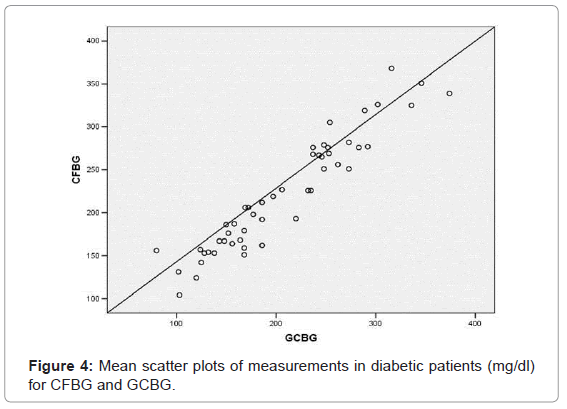

Diabetic patients [Group B] included 20 females and 30 males with a mean age of 50.38 ± 10.25 years old. Their mean blood level at fasting blood was 148.22 ± 42.04, capillary finger stick blood was 221.42 ± 66.14 and gingival crevicular blood was 207.14 ± 69.71. A statistically significant correlation (p=0.001) was found between CFBG and FBG (r=0.798); (Figure 2) GCBG and FBG (r=0.736) (Figure 3) and GCBG and CFBG (r=0.949) (Figure 4).

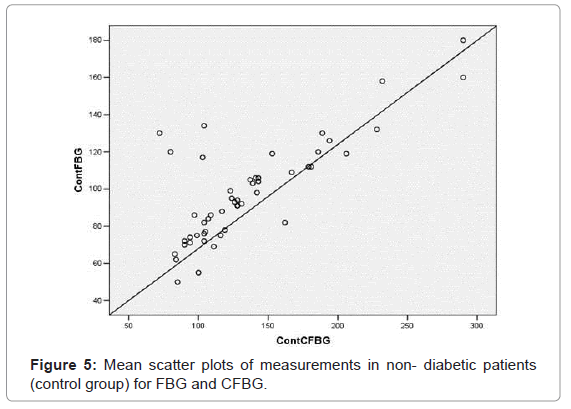

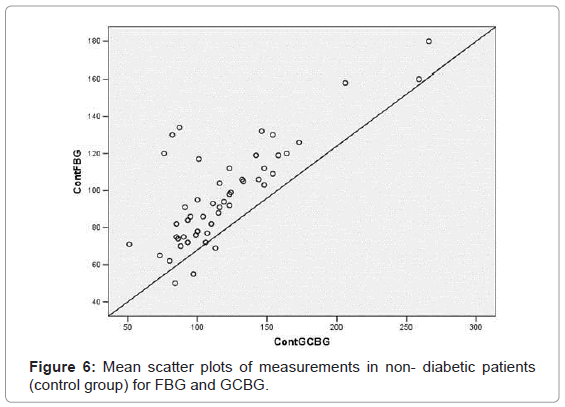

Non- diabetic individuals (control group) [Group C] included 32 females and 18 males with a mean age of 48.34 ± 13.99 years old. Their mean glucose level at fasting blood was 98.08 ± 27.44, capillary finger stick blood was 135.22 ± 49.88 and the gingival crevicular blood was 119.46 ± 41.90. A statistically significant correlation (p=0.001) was found between CFBG and FBG (r=0.783); (Figure 5) GCBG and FBG (r=0.784) (Figure 6) and GCBG and CFBG (r=0.934) (Figure 7).

Discussion

About one third of type 2 DM cases are undiagnosed and screening for such cases is highly recommended [7]. The American Diabetes Association recommends screening for diabetes should start at the age of 45 years and should be repeated every 3 years in individuals without risk factors, earlier and more often in those with risk factors for diabetes [8,12].

The primary methods used to diagnose diabetes mellitus and monitor blood glucose levels have traditionally been fasting blood glucose, a combination of fasting blood glucose with a 2-hour test after glucose loading (2-hour post-prandial) and oral glucose tolerance test [9,13].

These tests require fasting by the patient, tend to be highly dependent on patient compliance, and results are available at a subsequent visit (second appointment). Thus, more than one appointment is usually needed to assess the glycemic status and make necessary therapeutic decisions. Also, the information from a single laboratory test may not reflect patient’s current blood glucose status. Monitoring their blood glucose during the office visit may be a better alternative.

It may be more convenient for the dental surgeon to obtain blood sample from the gingival site. Stein and Nebbia [10] were the first to describe a chair-side method of diabetic screening with gingival blood. They transferred blood onto the test strip by wiping blood directly from hemorrhagic gingival tissue. Tsutsui et al. [11] reported the rubbing of blood onto the test strip from a blood-laden dental curette. Rubbing or direct wiping of intra-oral blood on to the test strip will not produce a uniformly timed reaction and may damage the strip’s chemical indicator surface [7]. Also, significant contamination may occur from saliva and oral debris present at the wiped gingival area or from plaque and crevicular fluid on the dental curette from its entry into the gingival sulcus. American Diabetes Association in their consensus statement on blood glucose monitoring (1987) [8] said that manual timing of the test strip reaction and the wiping of the test strip are significant sources of error when using glucose self monitors.

To over-come these errors, Parker et al. [12] used a glucometer, which is self- timing and requires no wiping. He used a plastic pipette, to reduce contamination of the sample with saliva, plaque, and debris. Beikler et al. [13] suggested direct use of test strip of glucometer to collect blood sample from gingiva. In contrast to Parker’s study, the sampling procedure used in this study was much easier to perform and less time consuming and required no additional tools to collect gingival crevicular blood.

Estimation of Gingival Crevicular blood glucose level can be done as an in-office screening procedure. In this study, ACCU-CHEK Active, Roche Diagnostics, USA is the glucometer used to measure the glucose levels in the blood which oozes out during routine probing. Measuring blood glucose with a glucometer is very sensitive since it can provide results with 2-3μl of blood within 10 seconds. It is less time consuming procedure and does not require any additional tools like sharp lancet for puncture. Even in case of very low gingival bleeding, glucose measurement is possible with a glucometer, due to low volume of blood (3μl) required to perform the analysis [14,15].

The mean age of the patients was in the range of 45-70 years, and DM is more prevalent in this age group. There were no drop-outs during the study. The main controversial issue is the reliability of glucometer, as they may show large deviations. When two sites were compared, good correlation was observed with no outliers. The results of this study in group A showed that there was a highly significant correlation (ICC: 0.98) between subsequent measurements of glucose concentrations in gingival crevicular blood samples of two sites of profuse bleeding on probing, and therefore, the device is reliable. In this study, significant correlation (r= 0.93, p<0.001) was found between gingival crevicular blood glucose levels and capillary finger stick blood glucose levels in diabetics and non- diabetics [Group B & C] Fasting blood glucose is always considered the gold standard. Considerable correlation (r=0.75, p<0.001) was found between levels of gingival crevicular blood glucose and fasting blood glucose both in diabetic patients and the normal population [Group B & C]. The scatter plots from Figure 2-7 indicate a good correlation between FBG, CFBG and GFBG in diabetic and non diabetic groups with no frequent outliers and a positive correlation. The results of our study are consistent with Beikler et al. [13], and Parker et al. [12] and Tsutsui et al. [11]

In the present study, 5 out of 30 (16%) periodontitis patients showed potential for diabetes, with the gingival crevicular blood glucose values (>200 mg/dl) significantly higher than normal. They were instructed to undertake routine fasting blood glucose test at a nearby laboratory for confirmatory purpose. These values were markedly higher than normal. Therefore they were referred to the physician for opinion and confirmation. They were diagnosed to be diabetic.

Though high correlation between gingival and finger stick samples were reported in these studies, the contamination of the blood sample from crevicular fluid is possible and inevitable. Moreover, it has been reported that the free glucose concentration in gingival fluid was influenced by local environmental factors such as the micro flora and the liberation and activation of hydrolyzing enzymes [12]. Thus, gingival crevicular blood after probing may not represent true capillary blood glucose measurement.

In our study, sample was collected from the capillaries on the outer surface of the gingiva, thus eliminating the possibility of contamination with crevicular fluid. None of the subjects under study reported pain or discomfort and no complications have been reported after sampling by this method. This method cannot be applied in cases where purulent exudates are found in pockets. This results in dilution of the blood sample and alteration of glucose levels.

Conclusion

Considering the correlation between gingival crevicular blood glucose and the other two standard methods for glucose estimation in diabetic and normal individuals, it is evident that the blood obtained during routine periodontal probing can be used for estimation of blood glucose levels. Hence, gingival crevicular blood is an efficient diagnostic tool for estimation of blood glucose levels in patients with or without diabetes mellitus. The technique described is safe, easy to perform, repeatable, comfortable for the patient, cost effective, and might therefore help to increase the frequency of diabetes screening in dental office.

Acknowledgements

This project was approved and funded by the Indian council of medical research.

Conflict of interest

The authors state that they do not have a conflict of interest.

References

- Kumar P, Clark M (2002) Clinical medicine fifth edition, Mcgraw Hill: 1077.

- Gensini GF, Modesti PA, Lopponi A, Collela A, Costagli G, et al. (1992) Diabetic disease and periodontal disease. Diabetes and periodontopathy. Minerva Stomatol 41: 391-399.

- Löe H (1993) Periodontal disease. The sixth complication of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 16: 329-334.

- Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ (1998) Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med 15: 539-553.

- Chopra P, Kumar TS (2011) Correlation of glucose level among venous, gingival and finger-prick blood samples in diabetic patients. J Indian SocPeriodontol 15: 288-291.

- Yamaguchi M, Kawabata Y, Kambe S, Wårdell K, Nystrom FH, et al. (2004) Non-invasive monitoring of gingival crevicular fluid for estimation of blood glucose level. Med BiolEngComput 42: 322-327.

- Müller HP, Behbehani E (2004) Screening of elevated glucose levels in gingival crevice blood using a novel, sensitive self-monitoring device. Med PrincPract 13: 361-365.

- Consensus statement on self-monitoring of blood glucose(1987). Diabetes Care 10: 95-99.

- Verma S, Bhat KM (2004) Diabetes mellitus--a modifier of periodontal disease expression. J IntAcadPeriodontol 6: 13-20.

- Stein GM, Nebbia AA (1969) A chairside method of diabetic screening with gingival blood. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 27: 607-612.

- Tsutsui P, Rich SK, Schonfeld SE (1985) Reliability of intraoral blood for diabetes screening. J Oral Med 40: 62-66.

- Parker RC, Rapley JW, Isley W, Spencer P, Killoy WJ (1993) Gingivalcrevicular blood for assessment of blood glucose in diabetic patients. J Periodontol 64: 666-672.

- Beikler T, Kuczek A, Petersilka G, Flemmig TF (2002) In-dental-office screening for diabetes mellitus using gingival crevicular blood. J ClinPeriodontol 29: 216-218.

- Mealey BL (1996) Periodontal implications: medically compromised patients. Ann Periodontol 1: 256-321.

Relevant Topics

- Advanced Bleeding Gums

- Advanced Receeding Gums

- Bleeding Gums

- Children’s Oral Health

- Coronal Fracture

- Dental Anestheia and Sedation

- Dental Plaque

- Dental Radiology

- Dentistry and Diabetes

- Fluoride Treatments

- Gum Cancer

- Gum Infection

- Occlusal Splint

- Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology

- Oral Hygiene

- Oral Hygiene Blogs

- Oral Hygiene Case Reports

- Oral Hygiene Practice

- Oral Leukoplakia

- Oral Microbiome

- Oral Rehydration

- Oral Surgery Special Issue

- Orthodontistry

- Periodontal Disease Management

- Periodontistry

- Root Canal Treatment

- Tele-Dentistry

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 16202

- [From(publication date):

December-2014 - Apr 26, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 11416

- PDF downloads : 4786