Decellularized and Dehydrated Human Amniotic Membrane in Wound Management: Modulation of Macrophage Differentiation and Activation

Received: 10-Aug-2022 / Manuscript No. JBTBM-22-71576 / Editor assigned: 12-Aug-2022 / PreQC No. JBTBM-22-71576(PQ) / Reviewed: 26-Aug-2022 / QC No. JBTBM-22-71576 / Revised: 30-Aug-2022 / Manuscript No. JBTBM-22-71576(R) / Accepted Date: 02-Sep-2022 / Published Date: 03-Sep-2022 DOI: 10.4172/2155-952X.1000289

Abstract

Successful application of biomaterials for wound healing requires extracellular matrix components capable of promoting endogenous regeneration. Macrophages are a type of monocyte that play a critical role in tissue regeneration and repair. In the early phases of wound healing, these cells orchestrate the inflammatory response, and in the later stages of wound healing, they mediate the resolution of wound healing. In chronic wounds, uncontrolled macrophage activation negatively impacts the wound healing process. The purpose of this study was to characterize the effect of a decellularized, dehydrated human amniotic membrane (DDHAM) on macrophage differentiation and activation from monocytes in vitro. Monocytes were isolated from the peripheral blood of healthy donors and cultured on standard tissue culture plates (CB), collagen type I-coated plates (COL), and on plates containing DDHAM. Proinflammatory (M1) macrophage differentiation was modeled by monocyte culture in the presence of granulocytemacrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and activation with a strong pro-inflammatory cocktail, consisting of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and interferon gamma (IFN-ɣ). The results showed that DDHAM enhanced monocyte differentiation in comparison with CB or COL as evident by increased cell size, viability, macrophage gene expression,and soluble factor secretion. Furthermore, macrophages differentiated on DDHAM and activated by inflammatory signals (LPS and IFN-ɣ) were impaired in their expression of a subset of LPS-inducible nuclear factor kappa-lightchain-enhancer of activated B cells target genes, with IL12β, coding for IL12p40 (subunit of IL12/23) being the most downregulated (p < 0.001). The effects of DDHAM on monocyte differentiation were found to be dependent upon β2 integrins. For the first time, these results indicate that a DDHAM can modulate macrophage behavior, by promoting their polarization into M2 phenotype, which is implicated in mediating a regenerative response and the resolution of healing, in a manner that is consistent with promoting vascular remodeling and tissue healing.

Keywords

Biomaterials; Decellularization; DDHAM; Extracellular matrix; Macrophages; Monocytes; Monocyte differentiation;Polarization; Scaffold; Wound healing

Introduction

Monocytes are large, phagocytic white blood cells that are part of the innate immune system [1]. Monocytes function as the host’s defense against infection and inflammation and play a critical role in tissue remodeling [2]. In wound healing, monocytes are one of the earliest cells recruited to the site of injury where they differentially contribute to all three overlapping phases of tissue healing and repair: inflammation, proliferation, and maturation [3]. When stimulated by invading cells, monocytes migrate from the bone marrow into circulation. Upon entering the tissue, monocytes differentiate into macrophages.

Macrophages are heterogeneous immune cells with great plasticity and diverse functional subsets [4]. They play a critical role in endogenous regeneration processes [4]. During wound healing, macrophages sequentially change their phenotypic polarization in response to temporal and spatial stimuli in their microenvironment [5-7].

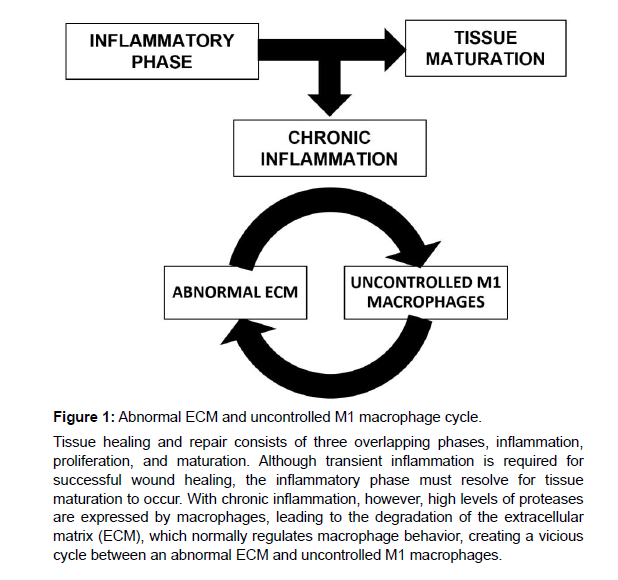

Polarized macrophages are traditionally categorized into classically activated M1 macrophages and alternatively activated M2 macrophages [8]. The M1 phenotype is present during the early stages of healing, orchestrating the inflammatory response [9], and in the later stages of healing, macrophages transition into a predominantly M2 phenotype, which mediates a regenerative response and the resolution of tissue remodeling and repair [9-11]. In line with this simplified, traditional classification, a higher ratio of M2 to M1 has been associated with constructive tissue remodeling [12-15]. While the classification of macrophages into M1 (pro-inflammatory) and M2 (anti-inflammatory) phenotypes facilitates discussion, it is an oversimplification. More accurately, polarized macrophages exist on a spectrum with several phenotypic subsets, ranging from M1 to M2a, M2b, M2c and M2d [16-18]. These specialized functional phenotypes are activated in response to specific stimuli. M1 is induced by exposure to interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and granulocyte macrophage stimulating factor (GM-CSF) [16]; M2a is induced by interleukin 4 (IL-4) and interleukin 13 (IL-13). M2b is induced by immune complexes, agonists of Tolllike receptor (TLR), and Fc receptors; M2c is induced by interleukin 10 (IL-10), transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), and glucocorticoids; and M2d is induced by TLR and adenosine A2 A receptor [16, 19]. Once activated, polarized macrophages differ in terms of cytokine production, surface marker expression, protein secretion, and gene expression [14]. Previous research has demonstrated that M1 macrophages are associated with the expression of TNF, interleukin 1 beta (IL1β), interleukin 6 (IL6), and interleukin 8 (IL8) genes, and M2 macrophages are associated with the expression of CD206, CCL22, and CCL18 genes [14, 20]. While broad, these distinct differences have allowed investigators to evaluate macrophages in terms of the M1 and M2 phenotypes. Macrophages play a significant role in wound healing, ensuring a timely transition through the phases of wound healing. Although transient inflammation is needed in the early stages of wound healing, the inflammatory phase must resolve to allow the healing cascade to progress through the proliferative and maturation phases [21]. Chronic, non-healing wounds, however, are unable to progress past the inflammatory stage [22], and macrophages persist in an uncontrolled pro-inflammatory M1 activation state [23]. In fact, there is evidence to suggest that a stalled pro-inflammatory macrophage phenotype exists in chronic wounds [23-25]. The extracellular matrix (ECM), which normally serves to regulate macrophage behavior, is dysfunctional in chronic wounds, due to the high expression of proteases by macrophages [26], creating a vicious cycle between an abnormal ECM and uncontrolled M1 macrophages (Figure 1). Application of decellularized ECM bio-scaffolds is one means of creating a reparative environment. The functional ECM is thought to actively direct macrophage polarization [15, 27-29], thereby, promoting tissue remodeling through the recruitment of endogenous cells, stimulation of angiogenesis, and attenuation of the inflammatory response. However, differences in source tissue and processing methodologies play a significant role in determining the patterns of macrophage activation by different biomaterials [30].

BIOVANCE® (Celularity Inc., Florham Park, NJ) is a decellularized, dehydrated human amniotic membrane (DDHAM) allograft. The decellularization process is designed to remove residual cells, cell debris, and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), leaving behind the native ECM, and creating a product essentially free of cells and cell debris. The composition of DDHAM is that of an ECM-like material with high collagen content, retaining key bioactive molecules, such as fibronectin, laminin, glycosaminoglycans, and elastin [31]. Moreover, this decellularized ECM does not contain extraneous growth factors or cytokines that can elicit an unpredictable host response [31]. DDHAM provides a tissue ECM scaffold for cell attachment and proliferation, supporting the body’s natural ability to restore tissue to a pre-wound state with minimal inflammation and scarring [32]. The purpose of this study was to characterize the effect of DDHAM on macrophage differentiation and activation from human monocytes in vitro. The authors hypothesize that DDHAM will modulate macrophage behavior by promoting polarization into the M2 phenotype in a manner consistent with tissue repair and regeneration.

Methods

DDHAM: BIOVANCE® is marketed as an advanced therapy for wound management in a broad range of wound indications and to replace or supplement damaged or inadequate integumental tissue. This product is regulated by the FDA as a human tissue-based product under Section 361 of the Public Health Service Act.

Protection of human research subjects: Since the testing materials are commercially available products and this study did not require direct interaction with human subjects (donors), institutional review board approval was not required.

Monocyte isolation: Monocytes (LeukoPaks, New Jersey Blood Services Scotch Plains, NJ, a division of New York Blood Center New York, NY), were isolated from the peripheral blood of healthy donors (N = 2). The peripheral blood was diluted 1:2 with sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and overlayed onto Ficoll-Paque Plus (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were harvested post density gradient centrifugation. Monocytes were isolated by positive selection from PBMC using CD14+ Micro beads, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany).

Monocyte co-culture with DDHAM and control surfaces: Monocytes were cultured in 24-well tissue culture plates (Corning) at 0.5x106 cells/mL in complete RPMI (Roswell Park Memorial Institute) media with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco®, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). For co-culture with DDHAM, 2x3cm DDHAM pieces were cut into two, and each piece was placed at the bottom of one well using sterile forceps. DDHAM was held in place by insertion of sterile Teflon inserts. DDHAM-containing wells were equilibrated in RPMI media for 1-2 hours, and media were removed completely prior to adding cells. For control surfaces, CellBind plates (CB) or collagen type I-coated plates (COL). Were used with Teflon inserts placed in each well.

Monocyte differentiation: For differentiation with GM-CSF, 100 ng/mL recombinant GM-CSF was used. For M1 differentiation, monocytes were cultured for 3 days with 100 ng/mL GM-CSF, after which, the medium was removed and replaced with complete RPMI medium containing 10 ng/mL LPS and 50 ng/mL IFN-ɣ. Cell lysates for gene expression and culture supernatants for cytokine profiling were collected up to 24 hours later.

Integrin β2 blocking studies: For integrin blocking studies, monocytes were incubated in Falcon tubes (Corning, Glendale, AZ) with an isotype (Bio Legend®, San Diego, CA) or β2 blocking antibody (azide-free, ultra-low endotoxin, clone TS1/18, Bio Legend®, San Diego, CA) at an experimentally determined optimal concentration of 10 μg/ mL – 25 μg/mL. Incubation was performed at room temperature for 30 to 60 minutes after which monocytes were placed in culture.

Flow cytometry: AccutaseTM Cell Detachment Solution was used to remove cells from all surfaces, according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Innovative Cell Technology, San Diego, CA). Antibodies were from Bio Legend (San Diego, CA) and BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA). Samples were analyzed on BD LSRFortessaTM Cell Analyzer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).

Multiplex analysis: Culture supernatants were analyzed using magnetic bead based multiplex kits (Millipore Sigma, Burlington, MA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Ribonucleic Acid (RNA) isolation and gene expression analysis: Cells were lysed by removing culture supernatants and incubated in 350 μL Buffer RLT (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) for 10 minutes. RNA was isolated using RNA isolation kits (RNeasy Mini Kit, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and converted to complementary DNA (cDNA) using SuperScript® III (Invitrogen by Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was performed using reagents and primers from SABiosciences (Frederick, MD).

Assessment of monocyte viability: Monocytes were isolated from peripheral blood of healthy donors and cultured on CB, COL, CB+GMCSF, and plates containing DDHAM. Four days later, the viability of cultured monocytes on CB, COL, CB+GM-CSF, and DDHAM was evaluated by a CyQuantTM Cell Proliferation Assay (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) to quantify the number of recovered cells. Results are expressed as % viability (N = 4).

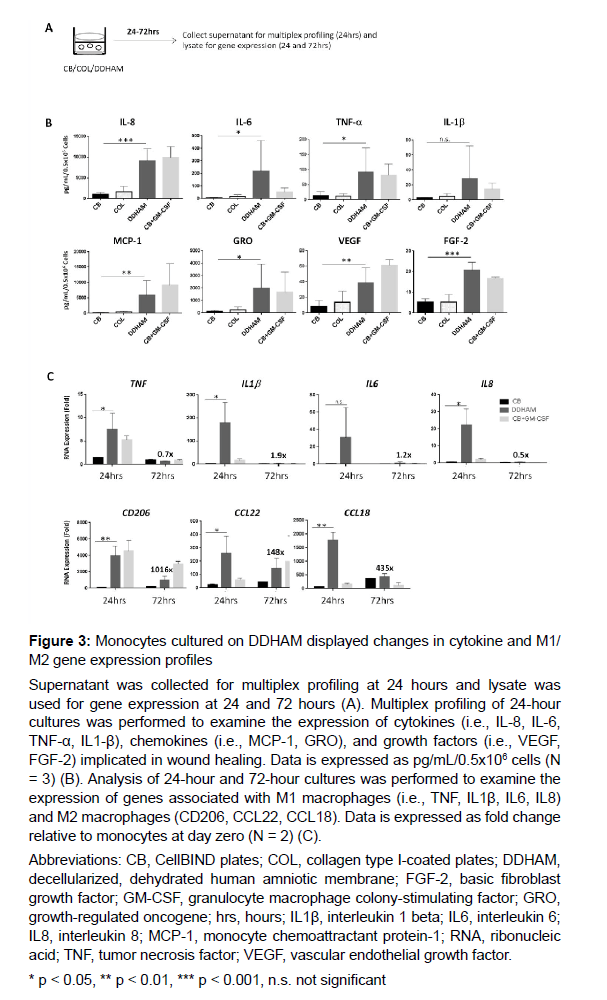

Assessment of cytokine, chemokine, and growth factor release by activated macrophages: Supernatant was collected for multiplex profiling at 24 hours and lysate was used for gene expression at 24 and 72 hours. Multiplex profiling of 24-hour cultures was performed to examine the expression of cytokines (i.e., interleukin 8 [IL-8], interleukin 6 [IL-6], tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α], interleukin 1 beta [IL-1β]), chemokines (i.e., monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 [MCP-1], growth-regulated oncogene [GRO]), and growth factors (i.e., vascular endothelial growth factor [VEGF], basic fibroblast growth factor [FGF-2]) implicated in wound healing. Analysis of 24-hour and 72-hour cultures was performed to examine the expression of genes associated with M1 macrophages (i.e., TNF, IL1β, IL6, IL8) and M2 macrophages (i.e., CD206, CCL22, CCL18).

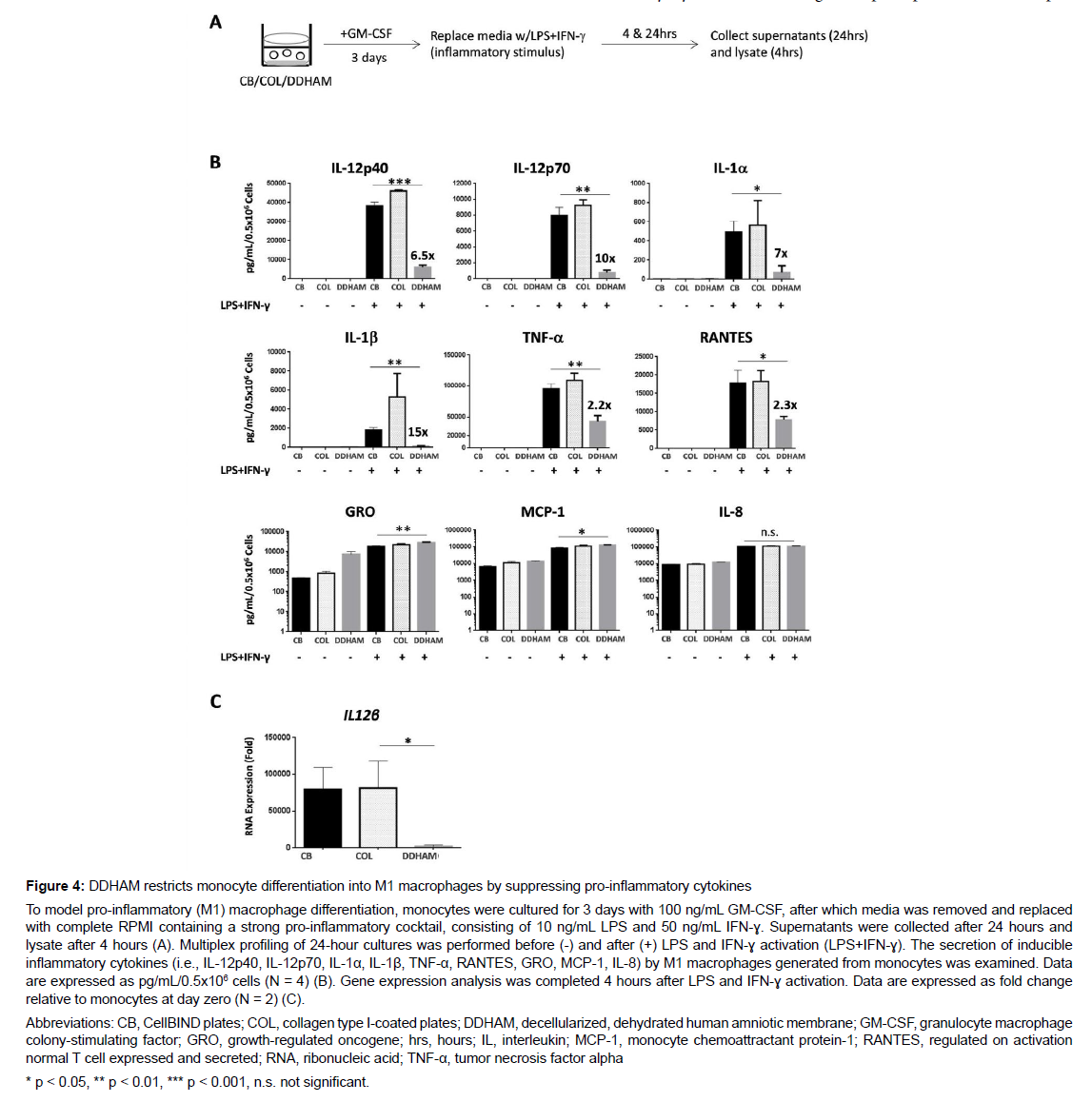

Assessment of pro-inflammatory macrophage differentiation: To model pro-inflammatory (M1) macrophage differentiation, monocytes were cultured for 3 days with 100 ng/mL GM-CSF, after which media was removed and replaced with complete RPMI containing a strong pro-inflammatory cocktail, consisting of 10 ng/mL LPS and 50 ng/ mL IFN-ɣ. Supernatants were collected after 24 hours and lysate after 4 hours. The secretion of inducible inflammatory cytokines (i.e., interleukin-12 subunit p40 [IL-12p40], interleukin-12 subunit p70 [IL-12p70], interleukin 1 alpha [IL-1α], IL-1β, TNF-α, Regulated on Activation, Normal T Expressed and Secreted [RANTES], GRO, MCP- 1, IL-8) by M1 macrophages generated from monocytes was examined. Multiplex profiling of 24-hour cultures was performed before and after LPS and IFN-ɣ activation. Data are expressed as pg/mL/0.5x106 cells (N = 4).

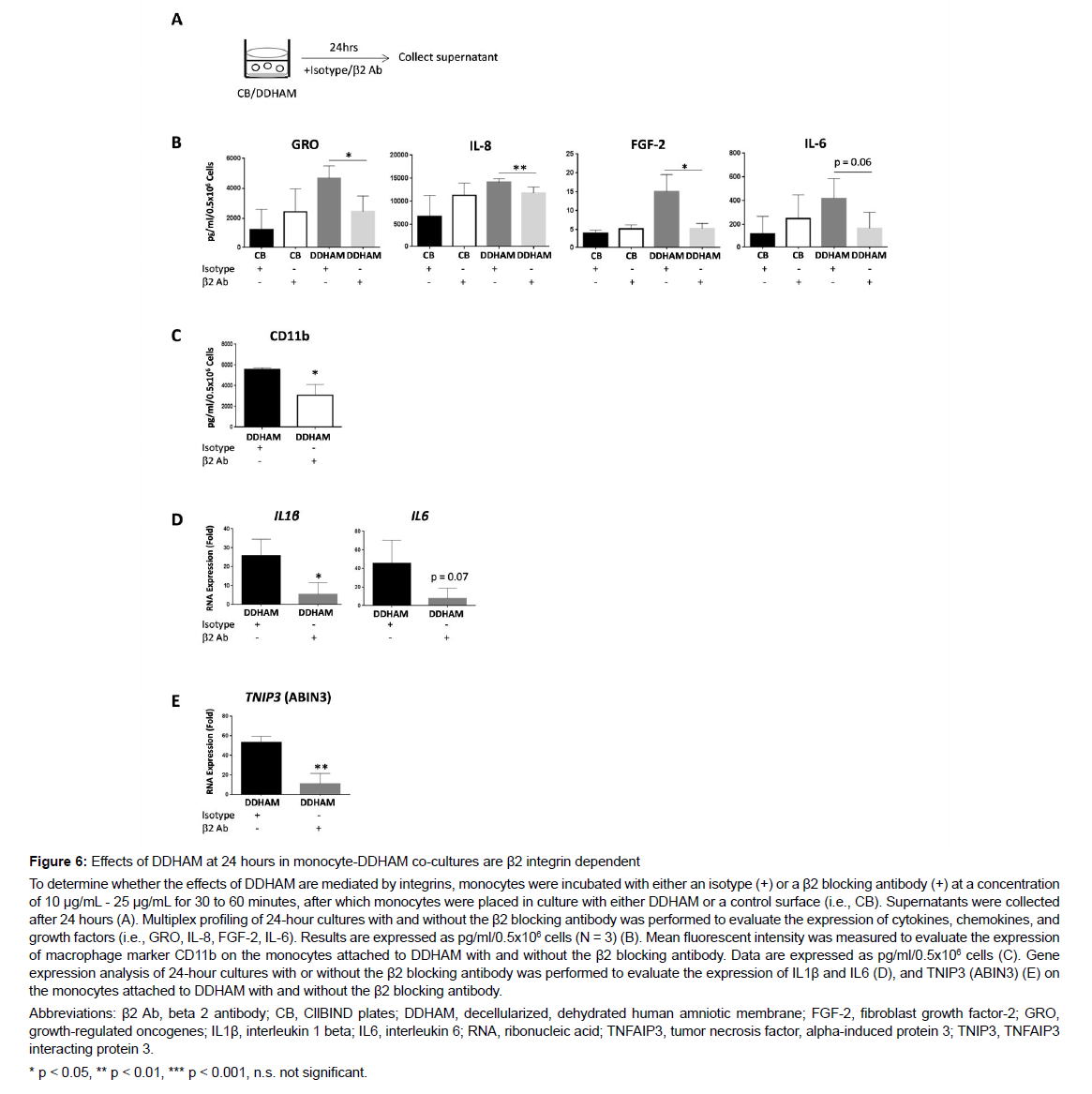

Assessment of β2 integrins on monocyte differentiation: Monocytes were incubated with either an isotype or a β2 blocking antibody (β2 Ab) at a concentration of 10 μg/mL - 25μg/mL. Incubation was performed at room temperature for 30 to 60 minutes, after which monocytes were co-cultured with DDHAM or a control surface (i.e., CB) in complete RPMI media with 10% FBS. After 24 hours, supernatants were collected. Multiplex profiling of 24-hour cultures with and without the β2 Ab was performed to evaluate the expression of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors (i.e., GRO, IL-8, FGF-2,IL-6). Data are expressed as pg/ml/0.5x106 cells (N = 3).

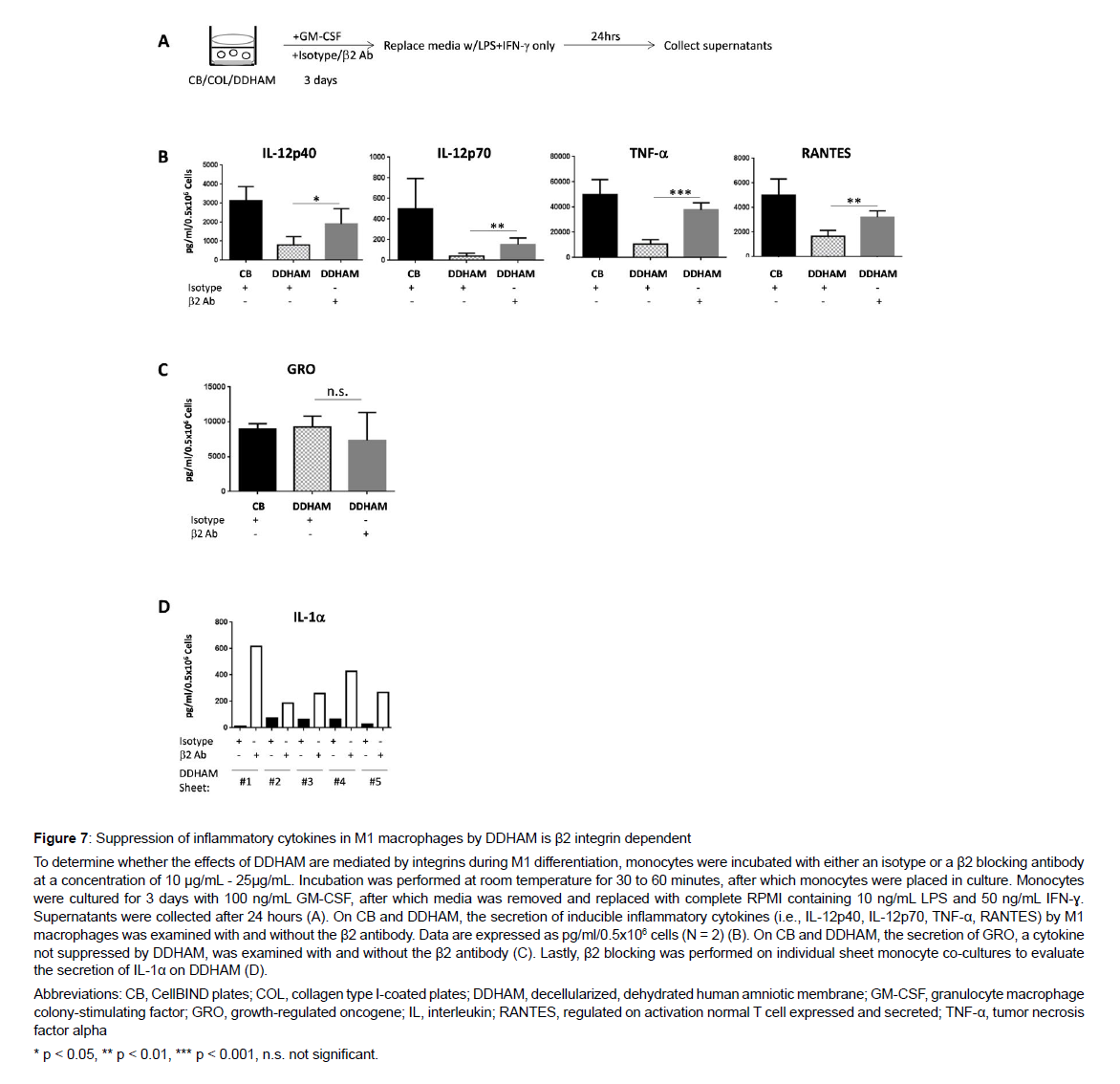

Assessment of β2 integrins on M1 differentiation: Monocytes were incubated with either an isotype or a β2 blocking antibody at a concentration of 10 μg/mL - 25 μg/mL. Incubation was performed at room temperature for 30 to 60 minutes, after which monocytes were placed in culture. Monocytes were cultured for 3 days with 100 ng/mL GM-CSF, after which media was removed and replaced with complete RPMI containing 10 ng/mL LPS and 50 ng/mL IFN-ɣ. Supernatants were collected after 24 hours. Multiplex profiling of 24-hour cultures with and without the β2 antibody was performed to evaluate the secretion of inducible inflammatory cytokines (i.e., IL-12p40, IL- 12p70, TNF-α, RANTES) by M1 macrophages with and without the β2 antibody. Data are expressed as pg/ml/0.5x106 cells (N = 2). Mean fluorescent intensity was measured to evaluate the expression of macrophage marker, CD11b, on the monocytes attached to DDHAM with and without the β2 blocking antibody. Gene expression analysis of 24-hour cultures with or without the β2 blocking antibody was performed to evaluate the expression of IL1β, IL6, and tumor necrosis factor, alpha-induced protein 3 [TNIP3 (ABIN3)] on the monocytes attached to DDHAM with and without the β2 blocking antibody.

Statistical Analysis: All analyses were conducted using Graph Pad Prism® (Version 4, San Diego, CA). Experiments were repeated three to five times and twice for gene expression data across time, inhibitors of cytokine expression across time, and gene expression analysis of 24-hour cultures with and without β2 antibody. Each experiment contained at least three replicates per condition tested to calculate significance. Data shown are pooled from multiple experiments and/ or representative of all experiments. Parametric unpaired t-tests were used to compare the variables. The significance level for all statistical tests was set at p = 0.05.

Results

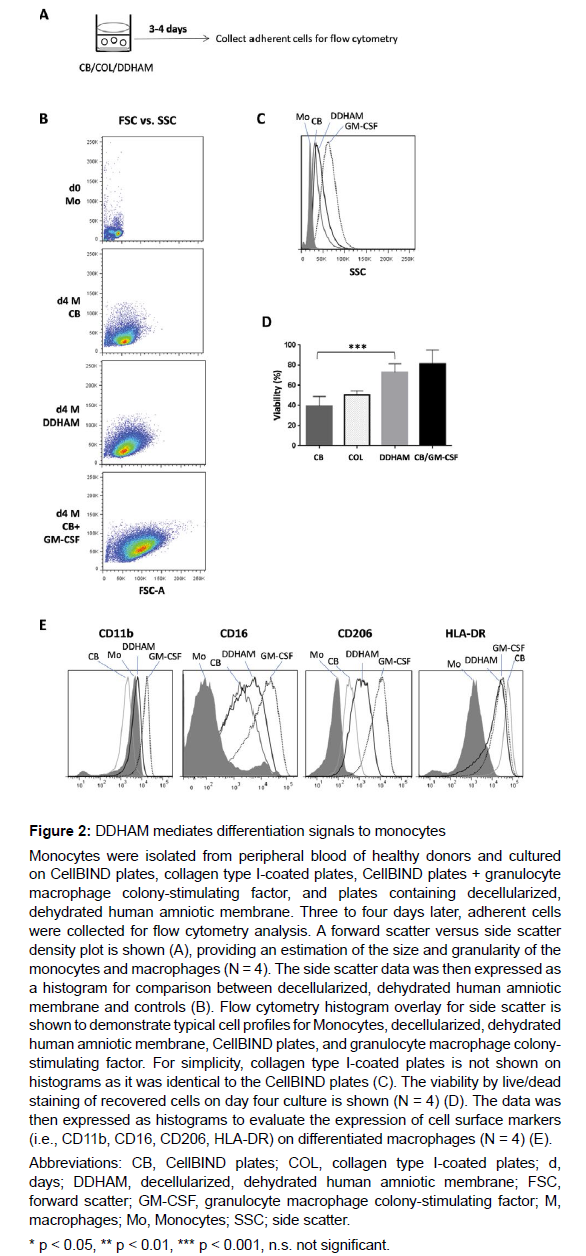

Isolation and characterization of human monocytes: Flow cytometry was used to evaluate the effects of DDHAM on the parameters of macrophage differentiation (Figure 2). Monocytes were co-cultured with DDHAM and control surfaces (i.e., CB, COL, CB+GM-CSF). Type I collagen was selected as control to provide a three-dimensional structure similar to the ECM found in vivo. Three to four days later, adherent cells were collected for flow cytometry analysis. The size and granularity of cultured monocytes was evaluated on day 0 and day 4.

On day 4, DDHAM mediated greater increases in the size and granularity of cultured monocytes compared with CB. The observed increases in size and granularity are characteristic of cells differentiated in the presence of macrophage differentiation factors, such as GMCSF. Also on day 4, the viability of cultured monocytes was evaluated and was found to be significantly greater on DDHAM compared with CB (p < 0.001, N = 4). Flow cytometry data, expressed as histograms, evaluated the expression of cell surface markers characteristic of differentiated macrophages (i.e., CD11b, CD16, CD206, HLA-DR). Compared with CB (and COL, data not shown), monocytes cultured on DDHAM showed increases in all cell surface markers of differentiated macrophages, except for HLA-DR. Overall, these results demonstrate that DDHAM mediates greater increases in the size and viability of cultured monocytes, characteristics of macrophage differentiation, which is driven by factors such as GM-CSF. Additionally, the expression of cell surface markers on differentiated macrophages was greater on DDHAM than CB or COL.

The effects of DDHAM on the release of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors by monocytes: The effects of DDHAM on cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors important for wound healing were examined as well as the effects of DDHAM on M1/M2 gene expression (Figure 3). Multiplex profiling of 24-hour culture supernatants was performed to examine the expression of cytokines (i.e., IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, IL-1β), chemokines (i.e., MCP-1, GRO), and growth factors (i.e., VEGF, FGF-2) implicated in wound healing. Data are expressed as pg/mL/0.5x106 cells (N = 3).

The expression of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors was significantly greater for DDHAM than the control (CB) for all factors (p < 0.05), except for IL-1β (p = 0.1). Analysis of 24-hour and 72-hour cultures was performed to examine the temporal regulation of monocyte gene expression. Genes associated with M1 macrophages included TNF, IL1β, IL6, and IL8, while genes associated with M2 macrophages included CD206, CCL22, and CCL18. Comparing DDHAM and CB at 24 hours, there was a statistically significant increase in the expression of genes associated with M1 macrophages, specifically, TNF, IL1β, and IL8 (p < 0.05). The difference in IL6 expression, however, was not significantly different between DDHAM and CB at 24 hours (p = 0.2). DDHAM transiently induced pro- inflammatory (M1) factors important for wound healing, although their levels returned to baseline (day 0) by day 3 of differentiation. Comparing DDHAM and CB at 24 hours,there was a statistically significant increase in the expression of genes associated with M2 macrophages (i.e., CD206, CCL22, and CCL18; p <0.05). When examined across time, DDHAM induced genes associated with M2 macrophages in a more sustained manner with their levels remaining high at day 3 compared to day 0 of differentiation. When considered collectively, monocytes cultured on DDHAM transiently increased expression of genes associated with M1 macrophages and displayed a more sustained expression of those associated with M2 macrophages, a pattern more similar to GM-CSF than the controls. In summary, monocytes cultured on DDHAM displayed changes in cytokine and M1/M2 gene expression profiles, like those cultured in the presence of GM-CSF. These results were not observed for CB or COL.

The effects of DDHAM on the release of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors by activated macrophages: To determine whether DDHAM-mediated signals can modulate M1 differentiation and activation, an inflammatory environment in culture to mimic chronic wound condition was modeled by exposing monocytes to strong inflammatory signals LPS and IFN-ɣ (Figure 4). Comparing DDHAM and CB, M1 macrophages generated from monocytes differentiated on DDHAM were significantly impaired in the secretion of inducible inflammatory cytokines, including IL-12p40 (p < 0.001), IL-12p70 (p < 0.01), IL-1α (p < 0.05), IL-1β (p < 0.01), TNF-α (p < 0.01), and RANTES (p < 0.05). These inflammatory cytokines are nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cell (NF-kB) targets and are negatively implicated in chronic wounds. However, the secretion of GRO, MCP-1, and IL-8 were not suppressed in M1 macrophages generated from monocytes differentiated on DDHAM but instead GRO (p < 0.01) and MCP-1 (p < 0.05) significantly increased. Additionally, M1 macrophage differentiation was evaluated at the gene expression level (i.e., IL12β RNA). Gene expression analysis was completed 4 hours after LPS and IFN-ɣ activation. Compared with COL, IL12β (encodes IL-12p40) expression by M1 macrophages differentiated on DDHAM was significantly lower (p < 0.05). In summary, M1 macrophages generated from monocytes differentiated on DDHAM, but not COL or CB, were significantly suppressed in secretion of inducible inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-12, IL-1α, IL-1β, TNF-α, and RANTES but not in that of GRO, MCP-1, or IL-8. Furthermore, reduced cytokine expression by M1 macrophages differentiated on DDHAM was also detectable at the gene expression level.

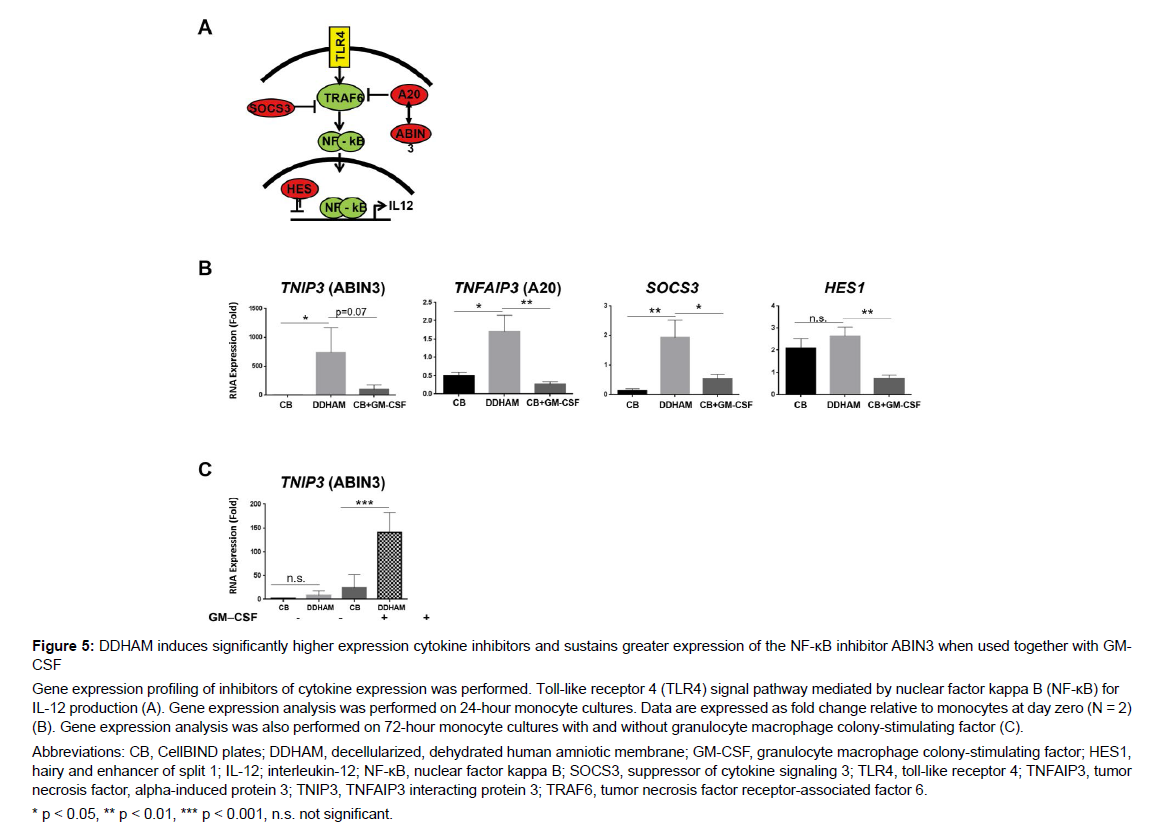

The effects of DDHAM on the expression of inhibitory proteins of the NFκβ pathway: Gene expression profiling was conducted to evaluate the effect of DDHAM on the expression of known inhibitors of cytokine expression (Figure 5). Gene expression analysis was performed on 24-hour and 72-hour monocyte cultures. At 24 hours, TNIP (encodes ABIN3), ANFAIP3 (encodes A20), SOCS3, and HES1 were examined, and at 72 hours, TNIP (encodes ABIN3) was examined with and without GM-CSF.

At 24 hours, DDHAM induced significantly higher expression of TNIP3 (ABIN3) compared with CB (p < 0.05). Compared with CB and CB+GM-CSF, DDHAM induced significantly higher expression of TNFAIP3 (A20) (p < 0.05) and SOCS3 (p < 0.05). Additionally, DDHAM induced significantly higher expression of HES1 than CB+GM-CSF (p < 0.01). However, the expression of HES1 was similar between DDHAM and CB (p > 0.05). At 72 hours, DDHAM sustained greater expression of TNIP3 (ABIN3), when used together with GM-CSF (p < 0.001). However, there was no significant difference in TNIP3 (ABIN3) expression between DDHAM and CB at 72-hours without GM-CSF (p > 0.05). These results demonstrate that DDHAM induces significantly higher expression of cytokine inhibitors (i.e., ABIN3, A20, HES1, and SOCS3) [33-36] at 24 hours and sustains a greater expression of the NK-κB inhibitor ABIN3 at 72 hours when used together with GM-CSF.

The effects of DDHAM on monocyte differentiation are β2 integrin dependent: β2 integrins are highly expressed in monocytes and their interaction with the ECM can modulate cytokine and by blocking β2 integrins. Mean fluorescent intensity of macrophage marker, CD11b, was measured to evaluate the expression of CD11b on monocytes attached to DDHAM with or without the β2 blocking antibody. On the monocytes attached to DDHAM, the expression of macrophage marker CD11b was also impaired by blocking β2 integrins (p < 0.05). Gene expression analysis of 24-hour cultures with or without the β2 blocking antibody was performed to evaluate the expression of IL1β RNA, IL6 RNA, and TNIP3 (ABIN3) RNA on DDHAM with and without the β2 blocking antibody. On DDHAM, gene expression was significantly impaired by blocking β2 integrins for IL1β RNA (p < 0.05) and TNIP3 (ABIN3) RNA (p < 0.01). These findings demonstrate that blocking β2 integrins impairs the ability of DDHAM to increase the expression of cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and macrophage marker CD11b. Moreover, by blocking β2 integrins, the effects of DDHAM on gene expression of IL1β and NFκβ inhibitor, TNIP3, are inhibited.

The effects of DDHAM on M1 differentiation are mediated by β2 integrins: The involvement of β2 integrins on M1 differentiation in the presence of DDHAM was also evaluated (Figure 7). In the presence of chemokine production [37-39]. To determine whether β2 integrins are required for the effects of DDHAM on monocyte differentiation and pro-inflammatory cytokine regulation, β2 integrins were blocked in a DDHAM-monocyte co-culture (Figure 6). On DDHAM, the expression of GRO (p < 0.05), IL-8 (p < 0.01), and FGF-2 (p < 0.05) was impaired by blocking β2 integrins. Mean fluorescent intensity of macrophage marker, CD11b, was measured to evaluate the expression of CD11b on monocytes attached to DDHAM with or without the β2 blocking antibody. On the monocytes attached to DDHAM, the expression of macrophage marker CD11b was also impaired by blocking β2 integrins (p < 0.05). Gene expression analysis of 24-hour cultures with or without the β2 blocking antibody was performed to evaluate the expression of IL1β RNA, IL6 RNA, and TNIP3 (ABIN3) RNA on DDHAM with and without the β2 blocking antibody. On DDHAM, gene expression was significantly impaired by blocking β2 integrins for IL1β RNA (p < 0.05) and TNIP3 (ABIN3) RNA (p < 0.01). These findings demonstrate that blocking β2 integrins impairs the ability of DDHAM to increase the expression of cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and macrophage marker CD11b. Moreover, by blocking β2 integrins, the effects of DDHAM on gene expression of IL1β and NFκβ inhibitor, TNIP3, are inhibited.

The effects of DDHAM on M1 differentiation are mediated by β2 integrins: The involvement of β2 integrins on M1 differentiation in the presence of DDHAM was also evaluated (Figure 7). In the presence of the β2 antibody, the ability of DDHAM to suppress IL-12p40 (p < 0.05),IL-12p70 (p < 0.01), TNF-α (p < 0.001), and RANTES (p < 0.01) was significantly impaired. However, there was no significant difference in the secretion of GRO by M1 macrophages with and without β2 antibody on DDHAM (p > 0.05). Additionally, by β2 blocking in individual sheet monocyte co-cultures, suppression of inflammatory cytokine IL-1α was reversed. In summary, upregulation of cytokine expression by β2 blocking in DDHAM-differentiated M1 macrophages was only detectable for cytokines that are suppressed by DDHAM and not for those such as GRO that are not suppressed by DDHAM.

Discussion

In chronic wounds, the wound remains in a persistent inflammatory state [40],tissue repair and regeneration do not occur, and the wound cannot heal [41]. Advanced therapies capable of correcting the cellular and molecular causes of prolonged inflammation are needed to promote the timely progression of the wound through the inflammatory phase. Macrophages are multifunctional cells whose phenotype changes during the stages of wound healing to regulate the wound healing process [18, 42]. Therefore, macrophages represent an attractive target to promote healing in chronic wounds. The purpose of this study was to characterize the effect of DDHAM on macrophage differentiation and activation from monocytes in vitro.

Results from this study show that DDHAM, a decellularized ECMbased product, can enhance monocyte differentiation, which was demonstrated by greater increases in the size, granularity, and viability of cultured monocytes as well as macrophage gene expression and soluble factor secretion. In addition, this study found that DDHAM modulates the expression of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors, involved in the wound healing process. More specifically, when cells are cultured on DDHAM, their expression of IL-8, IL-6, TNF-α, MCP-1, GRO, VEGF, and FGF-2 is increased, but not IL-1β. Notably, increased expression of VEGF and FGF-2 suggests that DDHAM may support wound healing through the stimulation of angiogenesis and epithelialization [43-46]. The lack of a significant change in the expression of IL-1β was not surprising given the relatively low amounts of IL-1β found in acute wound fluid [47]. In summary, these results suggest that DDHAM supported the release of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors, required for successful wound healing.

Furthermore, this study also demonstrated that DDHAM is capable of mediating changes in monocytes characteristic of differentiation into macrophages. Culturing cells on DDHAM resulted in a transient upregulation of both inhibitors of cytokine signaling (i.e., A20, ABIN3, SOCS3, and HES1) and M1 genes (i.e., TNF, IL1β, IL8, IL6) to levels equal to or higher than macrophage differentiation factor GM-CSF. DDHAM also supported a more sustained increase in M2 genes (i.e., CD206, CCL22, and CCL18), which was comparable to or higher than that of GM-CSF. These findings suggest that DDHAM supported an initial pro-inflammatory (M1) response and sustained a regenerative (M2) response, which aligns with a timely transition from an M1 to an M2 phenotype, as is observed in acute wound healing.

In the setting of M1 differentiation (GM-CSF and LPS+ IFN-ɣ), DDHAM mediated suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (i.e., IL-12, IL1-α, IL-1β, TNF-α, and RANTES) in macrophages. These effects were not seen in monocytes differentiated in the presence of collagen type I. In addition, in the presence of GM-CSF, DDHAM supported significantly higher expression of cytokine inhibitors and sustained greater expression of ABIN3, an NF-κB inhibitor, previously implicated in the suppression of signaling downstream of TLR [34], than GM-CSF alone. These findings suggest that cells cultured on DDHAM displayed restricted monocyte differentiation into M1 macrophages by suppressing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Of note, IFN-ɣ did not abrogate negative cytokine regulation of DDHAM, as previously described for other negative regulators of inflammatory cytokine expression [36, 48].

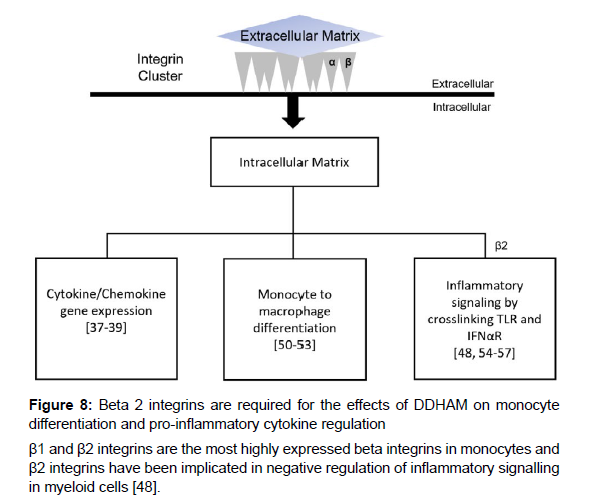

β1 and β2 integrins are the most highly expressed integrins in monocytes and are critical to innate and adaptive immune responses [49]. Interactions between β2 integrins and the ECM modulate cytokine and chemokine production [37-39], monocyte to macrophage differentiation [50-53], and inflammatory signaling via TLRs and interferon-α/β receptors (IFNAR) [48, 54-57], among other functions [49] (Figure 8). Previous research has implicated β2 integrins in the negative regulation of inflammatory signaling in myeloid cells [48]. To test whether β2 integrins are required for the effects of DDHAM on monocyte differentiation and pro-inflammatory cytokine regulation, an integrin β2 blocking study was performed by incubating monocytes with a β2 blocking antibody. These experiments demonstrated that the effects of DDHAM on monocyte differentiation and pro-inflammatory cytokine regulation are dependent on β2 integrins. While the underlying mechanisms were not examined in this study, previous data suggest that β2 integrin activation on monocytes in contact with DDHAM restricts their inflammatory potential through negative feedback loops [48] as well as through the induction of inhibitors of inflammatory cytokine expression, such as ABIN3.

Cells isolated from the human placenta possess desirable immunomodulatory properties [58], which has led to increasing research evaluating their application in regenerative medicine. A recent study by Magatti and colleagues demonstrated that human amniotic mesenchymal tissue cells (hAMTCs) and their conditioned medium benefit tissue repair by inducing the M1-to-M2 switch and enhancing the anti-inflammatory profile of M2 macrophage cells [59]. Furthermore, the study used a skin wound model in diabetic mice to evaluate whether conditioned media obtained from hAMTCs could accelerate wound closure and found a significant therapeutic effect [59]. As previously discussed, the present study found that monocytes cultured on DDHAM transiently increased expression of genes associated with M1 macrophages and displayed a more sustained expression of those associated with M2 macrophages. Moreover, DDHAM was found to restrict monocyte differentiation into M1 macrophages by suppressing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Notably, when considered in combination with the present study, similarities are established between the effects of hAMTCs and DDHAM on monocytes. Both hAMTCs and human AM tissue, devoid of cells, mediate monocyte differentiation and promote a proregenerative, anti-inflammatory M2 profile. An in vivo investigation is needed to determine whether DDHAM aids tissue repair, as was demonstrated for hAMTCs [59] and to understand the underlying mechanisms more fully through which hAMTCs and DDHAM exert their effects.

The study only evaluated the expression of IL12β. Future studies should also examine other M1 cytokines for a more comprehensive understanding of macrophage gene expression. The in vitro study design comes with inherent limitations as it is not able to mimic the complexity of in vivo macrophage activation with physiologic amounts of cytokines, growth factors, and interactions with other cells [30]. Thus, additional in vivo research is warranted to evaluate the clinical translation of these findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, these experiments demonstrated that DDHAM enhanced monocyte differentiation in comparison with tissue culture plastic or collagen type I-coated plates as evident by increased cell size, viability, macrophage gene expression, and soluble factor secretion. Furthermore, macrophages differentiated on DDHAM and activated by inflammatory signals (LPS and IFN-ɣ) were impaired in their expression of a subset of LPS-inducible NF-kB target genes, with IL12β (coding for IL12p40 subunit of IL12/23) being the most down regulated. The effects of DDHAM on monocyte differentiation were found to be dependent upon β2 integrins. These results indicate that a natural DDHAM can modulate macrophage behavior in a manner that is consistent with tissue healing as evidenced by attenuation of the inflammatory response and stimulation of angiogenesis.

Conflicts of Interest

Joseph Gleason, Xuan Guo, Adam Kuehn, Raja Sivalenka, Anna Gosiewska, Robert J. Hariri, and Stephen A. Brigido are salaried employees at Celularity Inc. Nicole M. Protzman serves as an independent contractor for Celularity Inc. and reports personal fees from Celularity Inc. during the study. Yong Mao has nothing to disclose.

Funding

This study was funded by Celularity Inc. (170 Park Avenue Florham Park, NJ).

Acknowledgement

We thank Drs. Ivana Djuretic, Mohit Bhatia, Raihana Zaka, Aleksandr Kaplunovsky, Wang Chuan, Jack L Wang, Vladimir Jankovic, Janice M. Smiell, and Wolfgang Hofgartner for their scientific and technical assistance in the study design and execution.

References

- Auffray C, Sieweke MH,Geissmann F (2009) Blood monocytes: development, heterogeneity, and relationship with dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol 27: 669-692.

- Yanez A, Coetzee SG, Olsson A, Muench DE, Berman BP, et al. (2017) Granulocyte-monocyte progenitors and monocyte-dendritic cell progenitors independently produce functionally distinct monocytes. Immunity 47: 890-902.e4.

- Lucas T, Waisman A, Ranjan R, Roes J, Krieg T, et al. (2010) Differential roles of macrophages in diverse phases of skin repair. J Immunol 184: 3964-3977.

- Wynn TA, Chawla A, Pollard JW (2013) Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease. Nature 496: 445-455.

- Porcheray F, Viaud S, Rimaniol AC, Leone C, Samah B, et al. (2005) Macrophage activation switching: an asset for the resolution of inflammation. Clin Exp Immunol 142: 481-489.

- Stout RD, Suttles J (2005) Immunosenescence and macrophage functional plasticity: dysregulation of macrophage function by age-associated microenvironmental changes. Immunol Rev 205: 60-71.

- Stout RD, Jiang C, Matta B, Tietzel I, Watkins SK, et al. (2005) Macrophages sequentially change their functional phenotype in response to changes in microenvironmental influences. J Immunol 175: 342-349.

- Mills CD, Kincaid K, Alt JM, Heilman MJ, Hill AM (2000) M-1/M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm. J Immunol 164: 6166-6173.

- Arnold L, Henry A, Poron F, Baba-Amer Y, Van Rooijen N, et al. (2007) Inflammatory monocytes recruited after skeletal muscle injury switch into antiinflammatory macrophages to support myogenesis. J Exp Med 204: 1057-1069.

- Spiller KL, Koh TJ (2017) Macrophage-based therapeutic strategies in regenerative medicine. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 122: 74-83.

- O'Brien EM, Risser GE, Spiller KL (2019) Sequential drug delivery to modulate macrophage behavior and enhance implant integration. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 149-150: 85-94.

- Roma-Lavisse C, Tagzirt M, Zawadzki C, Lorenzi R, Vincentelli A, et al. (2015) M1 and M2 macrophage proteolytic and angiogenic profile analysis in atherosclerotic patients reveals a distinctive profile in type 2 diabetes. Diab Vasc Dis Res 12: 279-289.

- Spiller KL, Anfang RR, Spiller KJ, Ng J, Nakazawa KR, et al. (2014) The role of macrophage phenotype in vascularization of tissue engineering scaffolds. Biomaterials 35: 4477-4488.

- Spiller KL, Nassiri S, Witherel CE, Anfang RR, Ng J, et al. (2015) Sequential delivery of immunomodulatory cytokines to facilitate the M1-to-M2 transition of macrophages and enhance vascularization of bone scaffolds. Biomaterials 37: 194-207.

- Brown BN, Valentin JE, Stewart-Akers AM, McCabe GP, Badylak SF (2009) Macrophage phenotype and remodeling outcomes in response to biologic scaffolds with and without a cellular component. Biomaterials 30: 1482-1491.

- Martinez FO, Gordon S (2014) The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. F1000 Prime Rep 6: 13.

- Graney PL, Ben-Shaul S, Landau S, Bajpai A, Singh B, et al. (2020) Macrophages of diverse phenotypes drive vascularization of engineered tissues. Sci Adv 6: eaay6391.

- Ferrante CJ, Leibovich SJ (2012) Regulation of macrophage polarization and wound healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 1: 10-16.

- Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, et al. (2004) The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol 25: 677-686.

- Xue J, Schmidt SV, Sander J, Draffehn A, Krebs W, et al. (2014) Transcriptome-based network analysis reveals a spectrum model of human macrophage activation. Immunity 40: 274-288.

- Eming SA, Krieg T, Davidson JM (2007) Inflammation in wound repair: molecular and cellular mechanisms. J Invest Dermatol 127: 514-525.

- Demidova-Rice TN, Hamblin MR, Herman IM (2012) Acute and impaired wound healing: pathophysiology and current methods for drug delivery, part 1: normal and chronic wounds: biology, causes, and approaches to care. Adv Skin Wound Care 25: 304-314.

- Sindrilaru A, Peters T, Wieschalka S, Baican C, Baican A, et al. (2011) An unrestrained proinflammatory M1 macrophage population induced by iron impairs wound healing in humans and mice. J Clin Invest 121: 985-997.

- Krzyszczyk P, Schloss R, Palmer A, Berthiaume F (2018) The role of macrophages in acute and chronic wound ealing and interventions to promote pro-wound healing phenotypes. Front Physiol 9: 419.

- Cairo G, Recalcati S, Mantovani A, Locati M (2011) Iron trafficking and metabolism in macrophages: contribution to the polarized phenotype. Trends Immunol 32: 241-247.

- Sorokin L (2010) The impact of the extracellular matrix on inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 10: 712-723.

- Tian G, Jiang S, Li J, Wei F, Li X, et al. (2021) Cell-free decellularized cartilage extracellular matrix scaffolds combined with interleukin 4 promote osteochondral repair through immunomodulatory macrophages: In vitro and in vivo preclinical study. Acta Biomater 127: 131-145.

- Brown BN, Ratner BD, Goodman SB, Amar S, Badylak SF (2012) Macrophage polarization: an opportunity for improved outcomes in biomaterials and regenerative medicine. Biomaterials 33: 3792-3802.

- Boersema GS, Grotenhuis N, Bayon Y, Lange JF, Bastiaansen-Jenniskens YM (2016) The effect of biomaterials used for tissue regeneration purposes on polarization of macrophages. Biores Open Access 5: 6-14.

- Huleihel L, Dziki JL, Bartolacci JG, Rausch T, Scarritt ME, et al. (2017) Macrophage phenotype in response to ECM bioscaffolds. Semin Immunol 29: 2-13.

- Bhatia M, Pereira M, Rana H, Stout B, Lewis C, et al. (2007) The mechanism of cell interaction and response on decellularized human amniotic membrane: implications in wound healing. Wounds 19: 207-217.

- Brigido SA, Carrington SC, Protzman NM (2018) The use of decellularized human placenta in full-thickness wound repair and periarticular soft tissue reconstruction: an update on regenerative healing. Clin Podiatr Med Surg 35: 95-104.

- Coornaert B, Carpentier I, Beyaert R (2009) A20: central gatekeeper in inflammation and immunity. J Biol Chem 284: 8217-8221.

- Verstrepen L, Carpentier I, Verhelst K, Beyaert R (2009) ABINs: A20 binding inhibitors of NF-kappa B and apoptosis signaling. Biochem Pharmacol 78: 105-114.

- Yoshimura A, Naka T, Kubo M (2007) SOCS proteins, cytokine signalling and immune regulation. Nat Rev Immunol 7: 454-465.

- Hu X, Chung AY, Wu I, Foldi J, Chen J, et al. (2008) Integrated regulation of Toll-like receptor responses by Notch and interferon-gamma pathways. Immunity 29: 691-703.

- Yurochko AD, Liu DY, Eierman D, Haskill S (1992) Integrins as a primary signal transduction molecule regulating monocyte immediate-early gene induction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89: 9034-9038.

- de Fougerolles AR, Koteliansky VE (2002) Regulation of monocyte gene expression by the extracellular matrix and its functional implications. Immunol Rev 186: 208-220.

- de Fougerolles AR, Chi-Rosso G, Bajardi A, Gotwals P, Green CD, et al. (2000) Global expression analysis of extracellular matrix-integrin interactions in monocytes. Immunity 13: 749-758.

- Zhao R, Liang H, Clarke E, Jackson C, Xue M (2016) Inflammation in chronic wounds. Int J Mol Sci 17: 2085.

- Frykberg RG, Banks J (2015) Challenges in the treatment of chronic wounds. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 4: 560-582.

- Mosser DM, Edwards JP (2008) Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol 8: 958-969.

- Bao P, Kodra A, Tomic-Canic M, Golinko MS, Ehrlich HP, et al. (2009) The role of vascular endothelial growth factor in wound healing. J Surg Res 153: 347-358.

- Koike Y, Yozaki M, Utani A, Murota H (2020) Fibroblast growth factor 2 accelerates the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in keratinocytes during wound healing process. Sci Rep 10: 18545.

- Werner S, Smola H, Liao X, Longaker MT, Krieg T, et al. (1994) The function of KGF in morphogenesis of epithelium and reepithelialization of wounds. Science 266: 819-822.

- Yun YR, Won JE, Jeon E, Lee S, Kang W, et al. (2010) Fibroblast growth factors: biology, function, and application for tissue regeneration. J Tissue Eng 2010: 218142.

- Grimstad O, Sandanger O, Ryan L, Otterdal K, Damaas JK, et al. (2011) Cellular sources and inducers of cytokines present in acute wound fluid. Wound Repair Regen 19: 337-347.

- Wang L, Gordon RA, Huynh L, Su X, Park Min KH, et al. (2010) Indirect inhibition of Toll-like receptor and type I interferon responses by ITAM-coupled receptors and integrins. Immunity 32: 518-530.

- Arnaout MA (2016) Biology and structure of leukocyte beta 2 integrins and their role in inflammation. F1000Res 5: F1000 Faculty Rev-2433.

- Coccia EM, Del Russo N, Stellacci E, Testa U, Marziali G, et al. (1999) STAT1 activation during monocyte to macrophage maturation: role of adhesion molecules. Int Immunol 11: 1075-1083.

- Jacob SS, Shastry P, Sudhakaran PR (2002) Monocyte-macrophage differentiation in vitro: modulation by extracellular matrix protein substratum. Mol Cell Biochem 233: 9-17.

- Joshi S, Singh AR, Zulcic M, Bao L, Messer K, et al. (2014) Rac2 controls tumor growth, metastasis and M1-M2 macrophage differentiation in vivo. PLoS One 9: e95893.

- Shi C, Zhang X, Chen Z, Sulaiman K, Feinberg MW, et al. (2004) Integrin engagement regulates monocyte differentiation through the forkhead transcription factor Foxp1. J Clin Invest 114: 408-418.

- Zeisel MB, Druet VA, Sibilia J, Klein JP, Quesniaux V, et al. (2005) Cross talk between MyD88 and focal adhesion kinase pathways. J Immunol 174: 7393-7397.

- Han C, Jin J, Xu S, Liu H, Li N, et al. (2010) Integrin CD11b negatively regulates TLR-triggered inflammatory responses by activating Syk and promoting degradation of MyD88 and TRIF via Cbl-b. Nat Immunol 11: 734-742.

- Yee NK, Hamerman JA (2013) β(2) integrins inhibit TLR responses by regulating NF-κB pathway and p38 MAPK activation. Eur J Immunol 43: 779-792.

- Gmyrek GB, Akilesh HM, Graham DB, Fuchs A, Yang L, et al. (2013) Loss of DAP12 and FcRgamma drives exaggerated IL-12 production and CD8(+) T cell response by CCR2(+) Mo-DCs. PLoS One 8: e76145.

- Parolini O, Alviano F, Betz AG, Bianchi DW, Gotherstrom C, et al. (2011) Meeting report of the first conference of the International Placenta Stem Cell Society (IPLASS). Placenta 32 Suppl 4: S285-S290.

- Magatti M, Vertua E, De Munari S, Caro M, Caruso M, et al. (2017) Human amnion favours tissue repair by inducing the M1-to-M2 switch and enhancing M2 macrophage features. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 11: 2895-2911.

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Google Scholar, Indexed at, Crossref

Citation: Gleason J, Guo X, Protzman NM, Mao Y, Kuehn A, et al. (2022) Decellularized and Dehydrated Human Amniotic Membrane in Wound Management: Modulation of Macrophage Differentiation and Activation. J Biotechnol Biomater, 12: 288. DOI: 10.4172/2155-952X.1000289

Copyright: © 2022 Gleason J. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 3231

- [From(publication date): 0-2022 - Dec 07, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 2737

- PDF downloads: 494