Research Article Open Access

Cyberbullying among Adolescents: A Comparison between Iran and Finland

Kaj Björkqvist*, Hassan Jaghoory MSS and Karin Österman

Developmental Psychology, Åbo akademi University, Vasa, Finland

- *Corresponding Author:

- Björkqvist K

Developmental Psychology

Åbo akademi University

Vasa, Finland

Tel: 358-45-8460100

E-mail: kaj.bjorkqvist@abo.fi

Received Date: June 08, 2015; Accepted Date: December 26, 2015; Published Date: December 29, 2015

Citation: Björkqvist K, Hassan Jaghoory MSS, Österman K (2015) Cyberbullying among Adolescents: A Comparison between Iran and Finland. J Child Adolesc Behav 3:265. doi:10.4172/2375-4494.1000265

Copyright: © 2015 Björkqvist K, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Child and Adolescent Behavior

Abstract

Objective: The study aimed at investigating differences in frequencies of both victimization and perpetration of cyberbullying among adolescents from Iran and Finland. Method: Data from a total of 1250 adolescents (615 boys, 635 girls) of three age groups (10, 13, and 15 years of age) were collected in Mashhad, Iran (n = 630) and Ostrobothnia, Finland (n = 620). The questionnaire consisted of variables measuring various types of cyberbullying, such as sending nasty text messages, nasty e-mails, and putting up nasty pictures and films on internet. Results: Both victimization and perpetration of cyberbullying of all kinds were clearly more frequent in Iran. Both sex and age differences occurred, but these showed different patterns in Iran and Finland. Conclusion: The overall higher levels of cyberbullying in Iran suggest that there are considerable cultural differences in the regulation of aggressive outlets among adolescents of the two countries studied. The variation in cyberbullying patterns due to sex and age in Iran and Finland points in the same direction.

Keywords

Cyberbullying; Aggression; Adolescence; Sex differences; Iran; Finland

Introduction

Tokunaga defined cyberbullying as follows: “Cyberbullying is any behavior performed through electronic or digital media by individuals or groups that repeatedly communicates hostile or aggressive messages intended to inflict harm or discomfort on others” [1]. However, it is not always easy to distinguish between what should be considered as bullying rather than as regular aggression. Olweus [2] pointed out two crucial aspects that distinguish between bullying and non-bullying aggression: aggression may be a single act, whereas bullying involves repeated acts; furthermore, bully-victim relationships characteristically have an imbalance of power, making it difficult for the victim to defend himself or herself [2]. The concept of a power imbalance in cyberbullying is more complicated than in traditional forms of bullying [3]. Accordingly, it may be difficult to conclusively show that you have a case of cyberbullying rather than a case of general cyber aggression at hand. For the sake of communication, we will, however, in the following use the concept of cyberbullying for describing the phenomenon.

Since the advent of the internet and smart phone technology, cyberbullying among adolescents has become a social problem of considerable proportions. Researchers worldwide agree on that more than a third of adolescents have experiences of cyberbullying. Hinduja and Patchin [4] found that more than 32% of boys and over 36% of girls have been victims of cyberbullying. Somewhat less, 18% of boys and 16% of girls, reported perpetrating others online, mostly in chat rooms. Mishna et al. [5] showed that over 30% of adolescent students are involved in cyberbullying either as victim or perpetrator, while 25% were involved as both bullies and victims. Females were more likely than males to be bully-victims. The amount of hours per day a student is on the internet was a risk factor.

Katzer et al. [6] reported that 43.1% of participants in chat rooms in Germany have been victimized by cyberbullying. Katzer [7] found that 47% of victims of cyberbullying knew their bullies from school, while 34% knew the bullies only from the internet; 19% knew them from both school and internet. Olenikin-Shemesh et al. [8] found that 32% of adolescents reported knowing someone who was victimized.

Brighi et al. [9] found that being either a direct or an indirect victim of traditional bullying was a very strong predictor for becoming also a victim of cyberbullying for both males and females Erentaite et al. [10] found that 35% of victims of traditional bullying were also bullied in cyberspace. Adolescents who were bullied, particularly indirectly and verbally, showed a higher risk of victimization in cyberspace a year later.

Vandebosch and Cleemput [11] found even higher figures: the majority of pupils at secondary school, or 63.8%, believed that cyberbullying was a big problem. They found that 61.9% of secondary school pupils had been victims, 52.5% had been perpetrators, and 76.3% had been bystanders to at least one potentially offensive internet and mobile phone incident during the last 3 months.

Concomitants of cyberbullying: Sourander et al. [12] suggested that both cyberbullying and cyber victimisation are associated with psychiatric and psychosomatic problems. Cyber victimization was related with living in a family with more than two parents, perceived difficulties, emotional and peer problems, whereas cyberbullying was related to perceived difficulties, hyperactivity, conduct problems, frequent smoking, and drunkenness. Yabbar [13] found that adolescents who suffer from depressive symptoms have three time greater risk to become targets of Internet harassment compared with adolescents with milder symptomatology. Olenikin-Shemesh et al. [7] also find higher scores of depressive mood in victims of cyberbullying, in comparison with non-victimized adolescents.

Loneliness has been shown to be a particularly important concomitant of cyberbullying, especially of victimization from cyberbullying. Sahin [14] found that there was a significant correlation between becoming a cyber-victim and loneliness among adolescents, regardless of gender. Olenikin-Shemesh et al. [8] also found that victimized adolescents have a higher sense of loneliness than nonvictimized adolescents. A study by Schultz-Krumbholz et al. [15] showed that high scores on both perpetration and victimization of cyberbullying were related to enhanced loneliness, but only in boys. Brighi et al. [9] found that low self-esteem in family relationships was a predictor for cyberbullying in boys, while loneliness in relationships with parents was a predictor for cyberbullying in girls.

Ortega et al. [16] suggested that bullying via mobile phone is less likely to provoke feelings of loneliness than bullying via the internet, or indirect bullying. They found that cyberbullying and indirect bullying produce similar emotional profiles.

Cyberbullying in Iran has hardly been researched at all. The present study was of explorative nature, and investigated both victimization from and perpetration of cyberbullying among adolescents of three age groups: 10, 13 and 15 years of age. The data was compared with data collected with the same instrument from a comparison group from Finland consisting of adolescents of the same age groups.

Method

Sample

Data from 630 school children from three age groups (10, 13, and 15 years of age) were collected in Mashhad, Iran, in both public and private schools (totaling 12 schools). Data from a comparison group (same age groups, n = 620, totaling 10 schools) from Ostrobothnia, Finland, was also collected. Participating schools were selected in order to be as representative as possible for the regions in question. The total sample consisted of 1250 adolescents (615 boys, 635 girls), mean age = 12.7 years, SD =2.1. The age distribution was similar in Iran and Finland, and among boys and girls.

Instrument

The questionnaire consisted of variables measuring various types of cyberbullying, such as sending nasty phone calls, nasty text messages, nasty e-mails, and putting up nasty pictures and films on Internet (Mini-DIA) [17]. For exact wordings of the items (Tables 1-4). The respondents had to respond on a Likert-type scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often), how often they had been exposed to these behaviors (victim version), and how often they themselves had exposed others to such behaviors (perpetrator version).

| F | Df | p ≤ | ηp2 | Group differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of Country | |||||

| Multivariate Analysis | 464.97 | 6, 1241 | .001 | .692 | |

| Univariate Analyses | |||||

| Another said nasty things to you on telephone | 537.58 | 1, 1246 | .001 | .301 | Iran > Finland |

| Another sentnasty SMS messages to you | 480.60 | “ | .001 | .278 | Iran > Finland |

| Another sent nasty e-mails to you | 604.47 | “ | .001 | .327 | Iran > Finland |

| Another put up nasty pictures of you on internet | 1549.83 | “ | .001 | .554 | Iran > Finland |

| Another filmed you while someone else was evil against you | 1756.78 | “ | .001 | .585 | Iran > Finland |

| Another filmed you while someone else was evil against you and then put the film on internet | 1514.34 | “ | .001 | .549 | Iran > Finland |

| Effect of Sex | |||||

| Multivariate Analysis | 7.17 | 6, 1241 | .001 | .034 | |

| Univariate Analyses | |||||

| Another said nasty things to you on telephone | 7.81 | 1, 1246 | .005 | .006 | ‚?? > ‚?? |

| Another sent nastySMS messages to you | 2.59 | ,, | ns | .002 | |

| Another sentnastye-mails to you | 5.51 | ,, | .019 | .004 | ‚?? > ‚?? |

| Another put up nasty pictures of you on internet | 0.80 | ,, | ns | .001 | |

| Another filmed you while someone else was evil against you | 22.83 | ,, | .001 | .018 | ‚?? > ‚?? |

| Another filmed you while someone else was evil against you and then put the film on internet | 3.17 | ,, | .075 | .003 | |

| Interaction effect Country x Sex | |||||

| Multivariate Analysis | 3.13 | 1, 1241 | .005 | .015 | |

| Univariate Analyses | |||||

| Another said nasty things to you on telephone | 1.22 | 6, 1241 | ns | .001 | |

| Another sent nastySMS messages to you | 10.15 | “ | .001 | .008 | Fi: ‚?? > ‚?? |

| Another sentnastye-mails to you | 7.86 | “ | .005 | .006 | Fi: ‚?? > ‚?? |

| Another put up nasty pictures of you on internet | 9.08 | “ | .003 | .007 | Fi: ‚?? > ‚?? |

| Another filmed you while someone else was evil against you | 3.77 | “ | .053 | .003 | |

| Another filmed you while someone else was evil against you and then put the film on internet | .97 | “ | ns | .001 | |

Table 1: Results of a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) measuring sex differences in victimization from cyberbullying among Iranian and Finnish adolescents 10, 13, and 15 Years of Age (N =1250), cf.

| F | df | p ≤ | ηp2 | Group differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of Country * | |||||

| Effect of Age | |||||

| Multivariate Analysis | 3.23 | 2, 2480 | .001 | .015 | |

| Univariate Analyses | |||||

| Another said nasty things to you on telephone | 5.51 | 2, 1244 | .004 | .009 | 15 > 13, 10 yrs |

| Another sent nastySMS messages to you | 4.81 | “ | .008 | .008 | 15 > 13, 10 yrs |

| Another sentnastye-mails to you | .40 | “ | ns | .001 | |

| Another put up nasty pictures of you on internet | 2.84 | “ | .06 | .005 | 10 > 13, 15 yrs |

| Another filmed you while someone else was evil against you | 1.52 | “ | ns | .002 | |

| Another filmed you while someone else was evil against you and then put the film on internet | 6.59 | “ | .001 | .010 | 10 > 13, 15 yrs |

| Interaction effect Country x Age | |||||

| Multivariate Analysis | 6.54 | 2, 2480 | .001 | .031 | |

| Univariate Analyses | |||||

| Another said nasty things to you on telephone | .38 | 2, 1244 | ns | .001 | |

| Another sent nastySMS messages to you | 11.32 | “ | .001 | .018 | Iran: 15 > 13, 10 yrs |

| Another sentnastye-mails to you | .82 | “ | ns | .001 | |

| Another put up nasty pictures of you on internet | 9.894 | “ | .001 | .016 | Iran: 10 > 13, 15 yrs |

| Another filmed you while someone else was evil against you | 4.79 | “ | .008 | .008 | Iran: 10 > 13, 15 yrs |

| Another filmed you while someone else was evil against you and then put the film on internet | 10.33 | “ | .001 | .016 | Iran: 10 > 13, 15 yrs |

Table 2: Results of a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) measuring age differences in victimization from cyberbullying among Iranian and Finnish Adolescents 10, 13, and 15 Years of Age (N = 1250), cf.

| F | df | p≤ | ηp2 | Group differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect ofCountry | |||||

| Multivariate Analysis | 615.86 | 6, 1235 | .001 | .750 | |

| Univariate Analyses | |||||

| You said nasty things to another on telephone | 654.29 | 1, 1240 | .001 | .345 | Iran > Finland |

| You sent nasty SMS messages to another | 658.28 | “ | .001 | .347 | Iran > Finland |

| You sent nastye-mails to another | 1608.60 | “ | .001 | .565 | Iran > Finland |

| You put up nasty pictures of another on internet | 2924.51 | “ | .001 | .702 | Iran > Finland |

| You filmed someone else while another was evil against him or her | 1428.18 | “ | .001 | .535 | Iran > Finland |

| You filmed someone else while another was evil against him or her and then you put the film on internet | 2843.08 | “ | .001 | .696 | Iran > Finland |

| Effect of Sex | |||||

| Multivariate Analysis | 3.17 | 1, 1235 | .004 | .015 | |

| Univariate Analyses | |||||

| You said nasty things to another on telephone | 0.06 | 1, 1240 | ns | .001 | |

| You sent nasty SMS messages to another | 0.17 | “ | ns | .001 | |

| You sente-mails to another | 0.02 | “ | ns | .001 | |

| You put up nasty pictures of another on internet | 6.17 | “ | .013 | .005 | ‚?? > ‚?? |

| You filmed someone else while another was evil against him or her | 8.77 | “ | .003 | .007 | ‚?? > ‚?? |

| You filmed someone else while another was evil against him or her and then you put the film on internet | 10.60 | “ | .001 | .008 | ‚?? > ‚?? |

| Interaction effect Country x Sex | |||||

| Multivariate Analysis | 3.87 | 6, 1235 | .001 | .018 | |

| Univariate Analyses | |||||

| You said nasty things to another on telephone | 9.42 | 1, 1240 | .002 | .008 | Fi: ‚?? > ‚?? |

| You sent nasty SMS messages to another | 11.10 | “ | .001 | .009 | Fi: ‚?? > ‚?? |

| You sent nastye-mails to another | 16.73 | “ | .001 | .013 | Fi: ‚?? > ‚?? |

| You put up nasty pictures of another on internet | 10.81 | “ | .001 | .009 | Fi: ‚?? > ‚?? |

| You filmed someone else while another was evil against him or her | 1.25 | “ | ns | .001 | |

| You filmed someone else while another was evil against him or her and then you put the film on internet | 4.27 | “ | .039 | .003 | Iran: ‚?? > ‚?? |

Table 3: Results of a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) measuring sex differences in perpetration of cyberbullying among Iranian and Finnish adolescents 10, 13, and 15 Years of Age (N =1,244), cf.

| F | Df | p≤ | ηp2 | Group differences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect ofCountry * | |||||

| Effect of Age | |||||

| Multivariate Analysis | 5.03 | 12, 2468 | .001 | .024 | |

| Univariate Analyses | |||||

| You said nasty things to another on telephone | 12.13 | 2, 1238 | .001 | .019 | 15 > 13, 10 yrs |

| You sent nasty SMS messages to another | 8.20 | “ | .001 | .013 | 15 > 13, 10 yrs |

| You sent nasty e-mails to another | .59 | “ | ns | .001 | |

| You put up nasty pictures of another on internet | 5.27 | “ | .005 | .008 | 10 > 13, 15 yrs |

| You filmed someone else while another was evil against him or her | 1.80 | “ | ns | .003 | |

| You filmed someone else while another was evil against him or her and then you put the film on internet | 3.91 | “ | .02 | .006 | 10, 15 > 13 yrs |

| Interaction effect Country x Age | |||||

| Multivariate Analysis | 4.88 | 12, 2468 | .001 | .023 | |

| Univariate Analyses | |||||

| You said nasty things to another on telephone | 3.09 | 2, 1238 | .046 | .005 | Iran: 15 > 13, 10 yrs |

| You sent nasty SMS messages to another | 7.86 | “ | .001 | .013 | Iran: 15 > 13, 10 yrs |

| You sent nastye-mails to another | 1.72 | “ | ns | .003 | |

| You put up nasty pictures of another on internet | 11.36 | “ | .001 | .018 | Iran: 10 > 15, 13 yrs |

| You filmed someone else while another was evil against him or her | 2.72 | “ | .066 | .004 | Iran: 10 > 13, 15 yrs |

| You filmed someone else while another was evil against him or her and then you put the film on internet | 10.39 | “ | .001 | .017 | Iran: 10 > 15, 13 yrs |

Table 4: Results of multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) measuring age differences in perpetration of cyberbullying among iranian and finnish adolescents 10, 13 and 15 Years of Age (N = 1,244), cf.

Procedure

Data was collected during regular school hours, by help of a paperand- pencil questionnaire. All pupils who were present filled in the questionnaires, the response rate thus being 100% of those present.

Strategy of analysis

A multivariate analysis of variance approach (MANOVA) was adopted for the study, using SPSS-21.

Ethical considerations: The study was approved by the ethical board of Åbo Akademi University, and conducted with the consent of school authorities in Iran and Finland, and the parents of the children.

Results

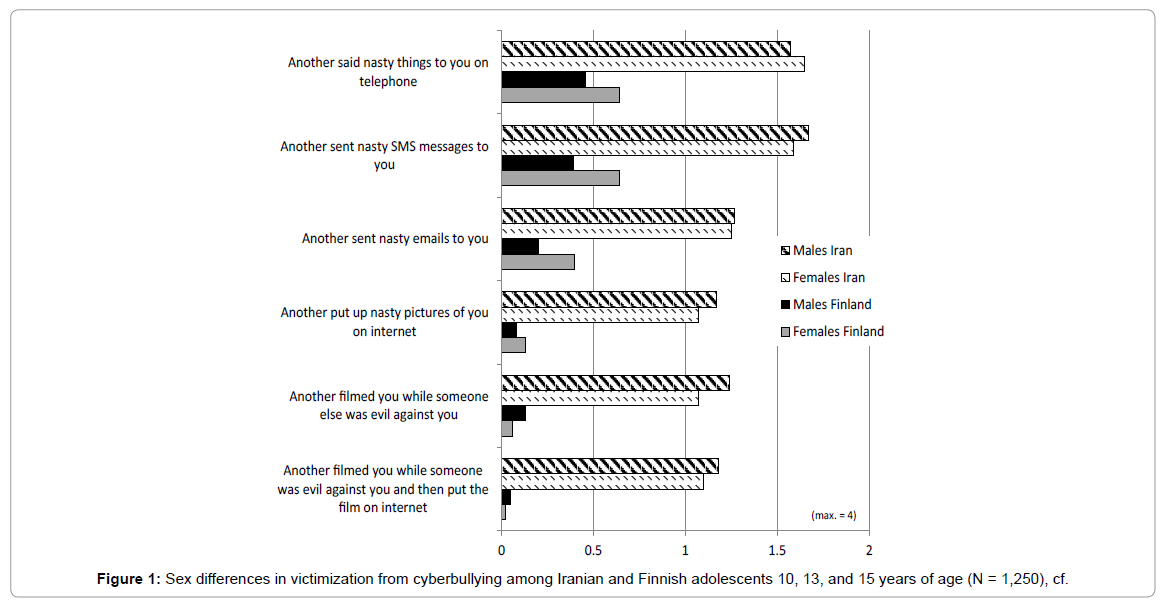

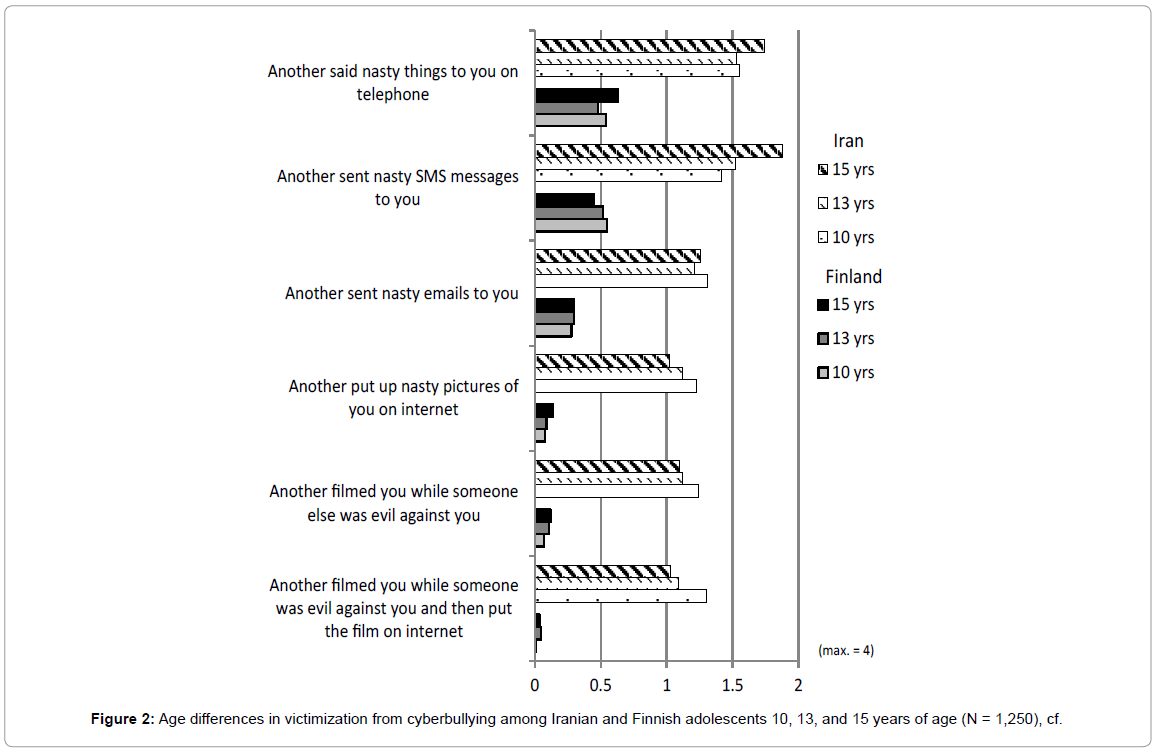

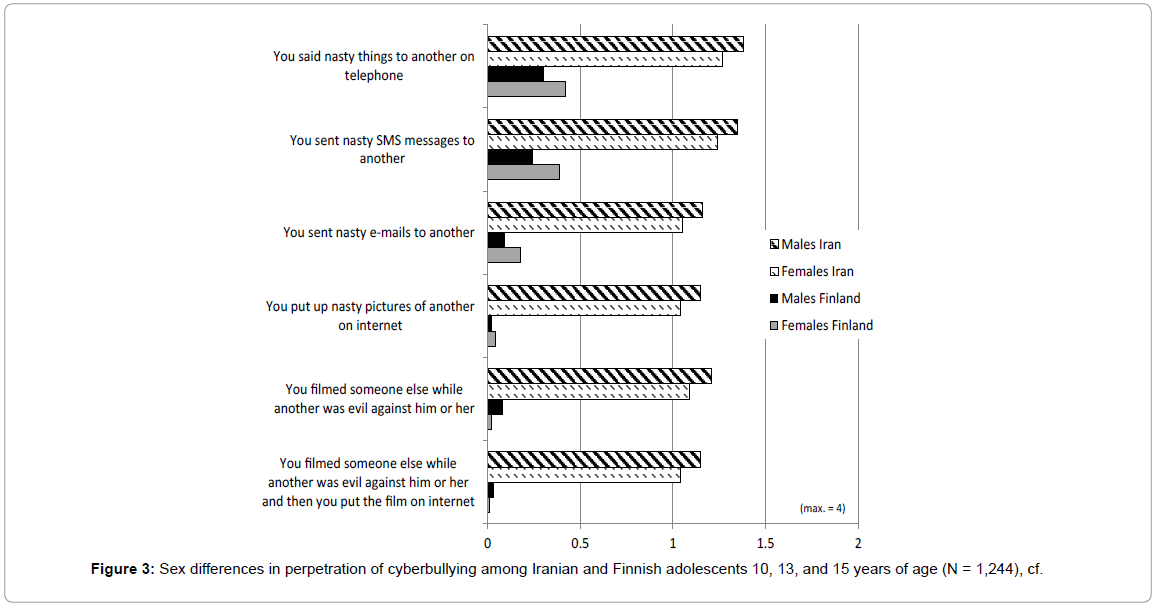

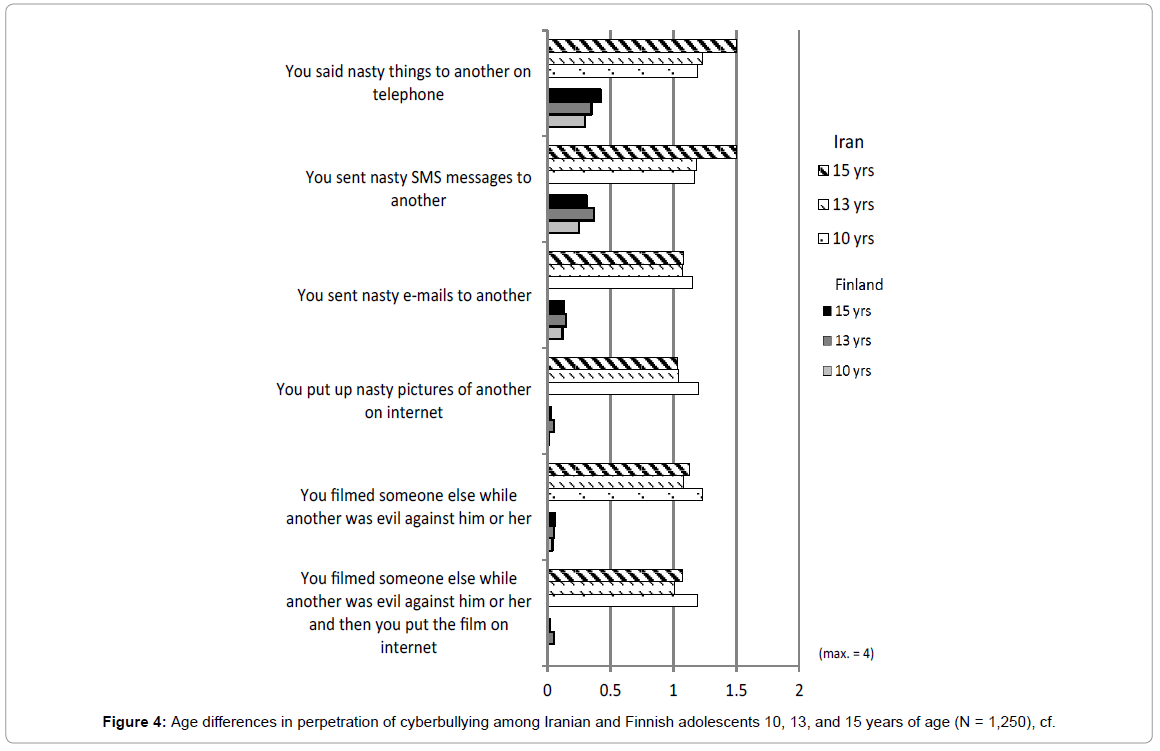

Four two-way MANOVA analyses were conducted: (1) Sex x Country, Victim Version of the questionnaire; (2) Country x Age group, Victim Version of the questionnaire; (3) Sex x Country, Perpetrator Version of the questionnaire; (4) Country x Age group, Perpetrator Version of the questionnaire. It was decided to perform two way-analyses rather than three-way (Country x Sex x Age group) analyses of variance in order to avoid having too small cells, and to make the interaction effects more intelligible. The results of these MANOVAs are presented in Tables 1-4 and Figures 1-4. The results for Country belonging is presented only in Tables 1 and 3, as they would have been identical in Tables 2 and 4.

The results of the first MANOVA (Country x Sex, Victim Version); Table 1 and Figure 1 reveal that victimization from cyberbullying was significantly more commonly reported in Iran. This was true in the case of all six forms of cyberbullying measured. A look at sex differences revealed at as far as the aggregated data from both countries was concerned, girls were more exposed to nasty telephone communications and nasty e-mails, while boys were more exposed to being filmed while someone else was evil against them.

An analysis of interaction effects of Country x Sex showed that sex differences were more prominent in the Finnish than in the Iranian sample: Finnish girls were more exposed to nasty SMS messages and nasty e-mails, while Finnish boys were more exposed to having nasty pictures of them put up on the Internet.

The results of the second MANOVA (Country x Age Group, Victim Version) are presented in Table 2 and Figure 2. The interaction effect between Country and Age group shows some unexpected features: In Iran, the 10-year-old age group had been exposed to having nasty pictures of themselves and nasty films of themselves put up on the internet to a higher extent than the older age groups. On the other hand, the Iranian 15-year-olds had been exposed to having nasty SMS messages sent to them than the younger age groups, which seems more in line with expectations.

The results of the third MANOVA (Country x Sex, Perpetrator Version) are presented in Table 3 and Figure 3. The main effect of Country reveals that Iranian adolescents performed more cyberbullying, of all kinds, than Finnish adolescents. The results are thus corresponding very well to those of the Victim Version of the questionnaire.

However, there were noteworthy interaction effects between Country an Sex. Finnish girls performed more cyberbullying than Finnish boys on four variables measured: they said more often nasty things on their mobile phone; they sent more often SMS messages with a nasty content; the same was true for nasty e-mails; and, they also more often put up nasty pictures on the internet. A similar sex difference did not exist within the Iranian sample.

On the other hand, Iranian boys more often than Finnish boys filmed others while doing something evil against them, and then put the film clip up on the Internet.

The results of the fourth MANOVA (Country x Age group, Perpetrator Version) are presented in Table 4 and Figure 4. Again, some noteworthy interaction effects were found. Iranian 15-year-olds seemed to use their mobile phones for bullying purposes more than the younger age groups: they more often said nasty things to others by telephone, and they also more often than the younger age groups sent nasty SMS messages.

However, the Iranian 10-year-olds scored higher than the older age groups on putting up nasty pictures on the Internet, and also on filming others while doing something evil, and then putting it up on the Internet. This age difference did not exist at all among the Finnish sample.

Discussion

The Iranian adolescents clearly had higher scores of cyberbullying, on all items, and both as perpetrators and victims. This finding might seem surprising, as Finland is technologically a highly developed country, where mobile phones and internet facilities are more easily available than in Iran. Accordingly, Finnish adolescents should have better opportunities for cyberbullying than their Iranian counterparts. The findings of this study does not offer a solution, but a higher level of aggressiveness in general among Iranian adolescents may be an explanation. It may reflect the difficult psychosocial challenges that the Iranian society is exposed to.

Another surprising finding was that the youngest age group among the Iranians, the 10-year-olds, had the highest scores of putting up humiliating pictures and films of others on the internet. Again, the present study does not offer a solution to why this is the case. In, Finland, this age difference did not occur. On the other hand, the 15-year-old Iranians used their mobile phones more for bullying purposes (both in the form of SMS messages and in the form of nasty phone calls) than the younger age groups. These discrepancies may reflect differences in maturity and adaptation to the cyber world.

In regard to sex differences, girls in Finland used cyberbullying significantly more than Finnish boys. In particular, Finnish girls sent nasty SMS messages, nasty e-mails, and put up humiliating pictures on the internet to a higher degree than Finnish boys. It appears that cyberbullying is a type of aggression that fits the mentality of Finnish girls. This sex difference was not found in Iran. The findings of the study thus reveal clear cultural differences in cyberbullying patterns among adolescents of the two countries. Further studies are required in order to explain these differences.

References

- Tokunaga RS (2010) Following you home from school: A critical review and synthesis of research on cyberbullying victimization. Comp Human Behav 26:277-287.

- Olweus D (1993) Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

- Dooley JJ, Cross D, Pyzalski J (2009) Cyberbullying versus face to face bullying: A theoretical and conceptual review. J Psychol 217:182-188.

- Hinduja S, Patchin J (2008) Cyberbullying: An exploratory analysis of factors related to offending and victimization. Deviant Behav 29:129-156.

- Mishna F, Khoury-Kassabri M, Gadalla T, Daciuk J (2012) Risk factors for involvement in cyber bullying: Victims, bullies and bully-victims. ChildrYouthServ Rev 34:63-70.

- Katzer C, FetchenhauerD, Blenchak F (2009) Cyberbullying: Who Are the Victims? A Comparison of Victimization in Internet Chatrooms and Victimization in School. J Media Psychol 21:25-36.

- Katzer C (2009) Cyberbullying in Germany.What has been done and what is going on. J Psychol 217:222-223.

- Olenkin-Shemesh D, Heiman T, Eden S (2012) Cyberbullying victimization in adolescents: Relationships with loneliness and depressive mood. EmotBehav Diff 17:361-374.

- Brighi A, Guarini A, Melotti G, Galli S, Gena AL (2012) Predictors of victimization across direct bullying, indirect bullying and cyberbullying. EmotBehav Diff 17:375-388.

- Erentaite R, Bergman LR, ŇĹukauskiene R (2012) Cross-contextual stability of bullying victimization: A person-oriented analysis of cyber- and traditional bullying experiences among adolescents. Scand J Psychol 53:181-190.

- Vanderbboch H, Cleemput K (2009) Cyberbullying among youngsters: Profiles of bullies and victims. New Media & Society 11:1349-1371.

- Sourander A, BrunsteinKlomek A, Ikonen M, Lindroos J, Luntamo T, et al. (2010) Psychosocial risk factors associated with cyberbullying among adolescents: a population-based study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67: 720-728.

- Ybarra ML (2004) Linkages between depressive symptomatology and Internet harassment among young regular Internet users. CyberpsycholBehav 7: 247-257.

- Sahin M (2012) The relationship between the cyberbullying/cybervictimization and loneliness among adolescents. Childr Youth Serv Rev 34:834-837.

- Shultze-Krumbholz A, Jäkel A, Schultze M, Scheithauer H (2012) Emotional and behavioural problems in the context of cyberbullying: A longitudinal study among German adolescents. EmotBehav Diff 17:329-345.

- Ortega R, Elipe P, Mora-Merchán JA, Calmaestra J, Vega E (2009) The emotional impact on victims of traditional bullying and cyberbullying. A study of Spanish adolescents. J Psychol 217:197-204.

- Karin Österman (2008) The Mini-Direct & Indirect Aggression Scales. Vasa, Finland: DeptDevPsychol, ÅboAkademi University, Finland.

Relevant Topics

- Adolescent Anxiety

- Adult Psychology

- Adult Sexual Behavior

- Anger Management

- Autism

- Behaviour

- Child Anxiety

- Child Health

- Child Mental Health

- Child Psychology

- Children Behavior

- Children Development

- Counselling

- Depression Disorders

- Digital Media Impact

- Eating disorder

- Mental Health Interventions

- Neuroscience

- Obeys Children

- Parental Care

- Risky Behavior

- Social-Emotional Learning (SEL)

- Societal Influence

- Trauma-Informed Care

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 12573

- [From(publication date):

December-2015 - Jul 03, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 11511

- PDF downloads : 1062