Cutaneous Eccrine Porocarcinoma: Diagnostic Challenge in Darker Skin Tones Individual

Received: 23-Jan-2024 / Manuscript No. DPO-24-125778 / Editor assigned: 26-Jan-2024 / PreQC No. DPO-24-125778 / Reviewed: 09-Feb-2024 / QC No. DPO-24-125778 / Revised: 16-Feb-2024 / Manuscript No. DPO-24-125778 / Published Date: 23-Feb-2024 DOI: 10.4172/2476-2024.9.1.226

Abstract

Cutaneous eccrine porocarcinoma is a rare and aggressive form of skin cancer that originates from the sweat glands. It can be particularly challenging to diagnose, especially in people with darker skin tones, as it may appear as a harmless lesion or imitate other skin conditions. A biopsy is essential for confirming the diagnosis, which involves examining the tissue sample under a microscope. Early detection is crucial to successful treatment, which may include surgical removal, radiation therapy, or chemotherapy. This case study features a 45-year-old man who visited our dermatology clinic with a painless, non-itchy lesion on the sole of his right big toe that had been present for ten years. It is suspected that the lesion may have developed from Eccrine Poroma.

Keywords: Biopsy; Carcinoma; Histopathology; Malignant lesions

Introduction

Eccrine Porocarcinoma is a rare and malignant type of sweat gland tumor that is still not fully understood. These tumors are classified into different types, including eccrine, apocrine, mixed, and unclassified tumors, based on the type of skin gland they originate from. Sweat gland porocarcinoma is a type of adnexal carcinoma that accounts for less than 0.01% of all skin malignancies and was first described by Pinkus and Mehregan in 1963 [1]. Eccrine Porocarcinomas have a tendency to affect the lower extremities of elderly people, but they can also occur in other parts of the body. These tumors can be challenging to diagnose, as their clinical presentation and histopathology findings can be similar to other types of skin tumors, particularly cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. As a result, a clinical diagnosis based solely on a physical exam can be confusing. In many cases, a definitive diagnosis of Eccrine Porocarcinoma requires a biopsy and histopathology examination. If this type of tumor is suspected, the patient should be referred to a dermatology specialist for further evaluation and treatment. It is important to diagnose and treat these tumors early, as they have the potential to spread to other parts of the body and become life- threatening.

Case Presentation

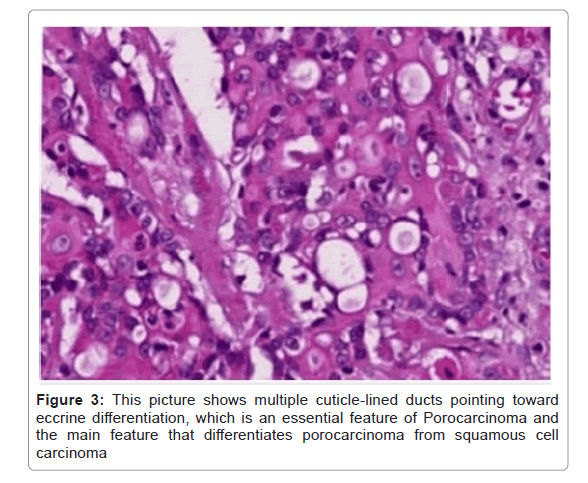

The patient who visited the dermatology clinic, Hiwot Fana Specialized Comprehensive Hospital was a 45-year-old male from Ethiopia. He presented to the clinic because of non-painful and non- itchy lesions on the plantar surface of his right big toe that had been present for 10 years. Initially, the lesion looked like warts, and over time, it had gradually increased in size. The patient reported that the lesion was now associated with intermittent bleeding. The patient is a soldier with no history of trauma to his foot, and he had not experienced a similar lesion or undergone any surgery. There were no other lesions on the other side of his body. Upon examination, a well-demarcated, 1 cm × 2 cm skin-colored/pinkish plaque with an ulcerative lesion was observed on the plantar surface of the right big toe. The lesion was exhibited in Figure 1. The lesion was non-painful and non-itchy. No palpable lymphadenopathy was found in all accessible areas. The CBC, OFT, chest X-ray, foot X-ray, and abdominal ultrasound were all performed and came back within the normal range. After the incisional biopsy was taken from the lesion and sent for histopathology, the histologic section showed skin-covered tissue with an area of ulceration. The underlying dermis exhibited infiltrative nests and broad anastomosing bands of mildly atypical round cells with scant to moderate eosinophilic- cytoplasm. In some areas, the tumor maintained a connection with the epidermis, and cuticle-lined ducts were seen pointing towards eccrine differentiation (Figures 2 and 3). A wide local surgical excision was performed, and the patient was given an appointment for follow-up in 4 months-6 months. Unfortunately, there is no postoperative photograph of the patient.

Results and Discussion

Due to the rarity of EPC, current epidemiological data are mainly derived from a few population-based as well as retrospective studies and meta-analyses. EPC has been shown to mostly affect the elderly population. Systematic reviews of 453, 206 and 120 cases have demonstrated a mean age of presentation ranging from 63.6 years to 65.6 years [1-4]. Similarly, analysis of the U.S. The National Cancer Database from 2004 to 2016 identified 611 cases of EPC with a mean age of presentation of 66 years [5]. The pathogenesis of EPC is not fully understood. It may develop de novo or arise from its benign counterpart, eccrine poroma, after a latency period of years or even decades [6]. This has been supported by published case series with long-term follow-up, as well as the results of a clinicopathologic study of 69 cases reporting that 18% of EPCs demonstrated adjacent features of benign poroma [7,8]. Diagnosis of EPC is challenging, as it is characterized by variable and non-specific clinical and histopathological findings, leading to diagnostic delay in most cases. Interestingly, the mean interval between tumor development and diagnosis has been reported to be five to nine years, but it may vary from days to even 60 years, according to the published literature [3,7-10]. Clinical differential diagnoses comprise benign or malignant lesions, such as pyogenic granuloma, seborrheic keratosis, Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC), Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC), Bowen’s disease, etc. diagnosis should be based on the combination of clinical, dermoscopically, histopathological, and immune histochemical findings. The clinical presentation of EPC is highly variable. Usually, it manifests as an erythematous, violaceous nodular lesion or, more rarely, as a polypoid plaque of violet or erythematous color, growing over weeks to months. It may be asymptomatic or present with itching, ulceration, and spontaneous bleeding. The latter should be clinically regarded as a sign of malignant transformation, and it has been found to represent a significantly worsening prognostic factor [4,6,11]. The tumor size at the time of diagnosis has been reported to range from 1 mm-130 mm, having a mean diameter of 23.88 mm [12]. Behbahani, et al. sought to correlate the tumor stage with the disease outcome. Except for the strong association of metastatic disease with a worse prognosis, a larger tumor size was also independently associated with decreased overall survival [12]. In a study of 69 cases, as well as a SEER analysis of 563 cases, the lower extremities were found to be the most commonly affected body site (33.7%-44%), followed by the head and neck (18%-30.6%) and trunk (19.524%) [8,13]. The histopathological characteristics of EPC in hematoxylin and eosin staining are diverse and may pose difficulties in histopathological differential diagnosis of EPCs, mainly from SCC. In most cases, large poromatous basaloid epithelial cells exhibiting ductal differentiation and cytologic atypia are observed [10]. In a meta- analysis of 120 EPCs, 25% and 23.4% of cases showed squamous and clear cell differentiation respectively while in another study of 33 cases, squamous cell differentiation was observed on 422% and melanocyte colonization in 21% of EPCs [4,10]. Complete surgical excision should be performed in resectable cases to achieve local control of the disease. According to the literature, Wide Local Excision (WLE) with at least 2-mm 6 safety margins constitutes the most commonly applied procedure associated with low recurrence rates and increased survival, as also demonstrated by a meta-analysis of 120 cases of head and neck EPCs, showing that the lack of WLE or Mohs Micrographic Surgery (MMS) was associated with worse prognosis and decreased overall survival (p<0.001) [4]. Comparison of these treatment modalities revealed a statistical significance regarding recurrence rates (25.3% vs. 0.0% for WLE and MMS, respectively), although this result should be evaluated with caution due to the lack of randomization between the two surgical procedures [4].

Conclusion

Despite the complex nature of EPC, proper care, support, and resources can make a significant difference. With accurate diagnosis, multidisciplinary management, and early intervention, those dealing with EPC can find hope and inspiration.

The presented case underscores the diagnostic challenges and clinical complexities associated with Eccrine Porocarcinoma (EPC), a rare and aggressive form of skin cancer originating from sweat glands. The case of a 45-year-old male with a longstanding lesion on the plantar surface of his right big toe highlights the importance of considering EPC in the differential diagnosis of cutaneous lesions, particularly when presenting in atypical locations or with unusual clinical features. Early recognition and accurate diagnosis of EPC are paramount for timely intervention and improved outcomes.

Disclosures

Human subjects: Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study. Conflicts of interest: In compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the following: Payment/services info: All authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work. Financial relationships: All authors have declared that they have no financial relationships at present or within the previous three years with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work. Other relationships: All authors have declared that there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Acknowledgements

I want to express my sincere gratitude to the staff of the Dermatovenereology Department at the College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University. They provided me with invaluable support while preparing this manuscript. I also extend my thanks to the Department of Pathology staff for assisting me in searching and preparing the histopathological data for this case report. Finally, I would like to thank my partner, Tsion D, for her unwavering support. She helped me in searching through journals, and books, and correcting technical errors.

References

- Nazemi A, Higgins S, Swift R, In G, Miller K, et al. (2018) Eccrine porocarcinoma: New insights and a systematic review of the literature. Derm Surg 44:1247-1261.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Elder, Scolyer RA, Willemze R (2018) Appendagealtumorss. In WHO Classification of Skin Tumours 4th edn, International Agency for Research on Cancer. 11:159.

- Pinkus H, Mehregan AH (1963) Epidermotropic eccrine carcinoma. A case combining features of eccrine poroma and paget’s dermatosis. Arch Derm 88:597-606.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mishima Y, Morioka S (1969) Oncogenic differentiation of the intraepidermal eccrine sweat duct: Eccrine poroma, poroepitheliom,a and porocarcinoma. Dermatologica 138:238-250.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Salih AM, Kakamad FH, Baba HO, Salih RQ, Hawbash MR, et al. (2017) Porocarcinoma; presentation and management, a meta-analysis of 453 cases. Ann med surg 20:74-79.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Le NS, Janik S, Liu DT, Grasl S, Faisal M, et al. (2020) Eccrine porocarcinoma of the head and neck: Metaanalysis of 120 cases. Head neck 42:2644–2659.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Behbahani S, Malerba S, Karanfilian KM, Warren CJ, Alhatem A, et al. (2020) Demographics and outcomes of eccrine porocarcinoma: Results from the National Cancer Database. Br J Dermatol. 183:161.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Robson A, Greene J, Ansari N, Kim B, Seed PT, et al. (2001) Eccrine porocarcinoma (malignant eccrine poroma): A Clinicopathologic study of 69 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 25:710-720.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shaw M, McKee PH, Lowe D, Black MM (1982) Malignant eccrine poroma: A study of twentyseven cases. Br J Dermatol 107:675-680.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Belin E, Ezzedine K, Stanislas S, Lalanne N, Beylot-Barry M, et al. (2011) Factors in the surgical management of primary eccrine porocarcinoma: Prognostic histological factors can guide the surgical procedure. Br J Dermatol 165:985-989.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Juay L, Choi E, Huang J, Jaffar H, Ho SAJE (2022) Unusual presentations of eccrine porocarcinoma. Skin Appendage Disord 8:61-64.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Behbahani S, Malerba S, Karanfilian KM, Warren CJ, Alhatem A, et al. (2020) Demographics and outcomes of eccrine porocarcinoma: Results from the National Cancer Database. Br J Dermatol 183:161.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scampa M, Merat R, Kalbermatten DF, Oranges CM (2022) Head and neck porocarcinoma: SEER analysis of epidemiology and survival. J Clin Med 11:2185.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Citation: Babeta FA, Fantaye AB, Mekonnen YG (2024) Cutaneous Eccrine Porocarcinoma: Diagnostic Challenge in Darker Skin Tones Individual. Diagnos Pathol Open 9:226. DOI: 10.4172/2476-2024.9.1.226

Copyright: © 2024 Babeta FA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 1028

- [From(publication date): 0-2024 - Mar 31, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 809

- PDF downloads: 219