"Correlation of psychological disorder between depression in dementia"- A prospective study

DOI: 10.4172/1522-4821.1000495

Abstract

Depression is very common among people with Alzheimer’s, especially during the early and middle stages. Treatment is available and can make a significant difference in quality of life. It is not only associated with psychological consequences but can also worse the condition of asthma, arthritis, diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular diseases and obesity are few to name. Few symptoms observed in depression and dementia is very similar like apathy, Loss of interest in activities and hobbies, social withdrawal and Isolation, Trouble concentrating. It becomes very difficult to diagnose those symptoms in the early stages. The time diagnosis is performed it becomes very late for the early treatment which is the worse condition faced by many suffering from depression. It is very important to identify such conditions in early stages where treatment can be a source of promising effect to treat other psychological and other system disorders.

Keywords: Depression, Alzheimer’s Disease, Dementia, Psychological Disorder

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the leading neurodegenerative cause of dementia in the elderly. Thus far, there is no curative treatment for this devastating condition, thereby creating significant social and medical burdens. AD is characterized by progressive cognitive decline along with various neuropsychiatric symptoms, including depression and psychosis. Interestingly, a number of proposed mechanisms for depression appear to be similar to those implicated in neurodegenerative diseases, including AD. For example, diminishing neurotrophic factors and neuroinflammation observed in depression are found to be associated with the development of AD.

Plaques and neuro fibrillary tangles [NFT] are the most prominent histological features in the AD brain. NFT are positively associated with clinical severity in AD patients, estimated by the Clinical Dementia Rating and Mini-Mental State Examination scores.

A consistent finding in patients with depression is elevated levels of the stress hormone cortisol. Patients with Cushing’s syndrome – a state of hypercortisolaemia – frequently present depressive symptoms

Dysregulation of monoaminergic neurotransmitters

The earliest mechanism found to be involved in the aetiology of depression is the dysregulation of monoaminergic neurotransmitters like serotonin which plays important role in regulation of mood. (Alexopoulos et al., 2008)

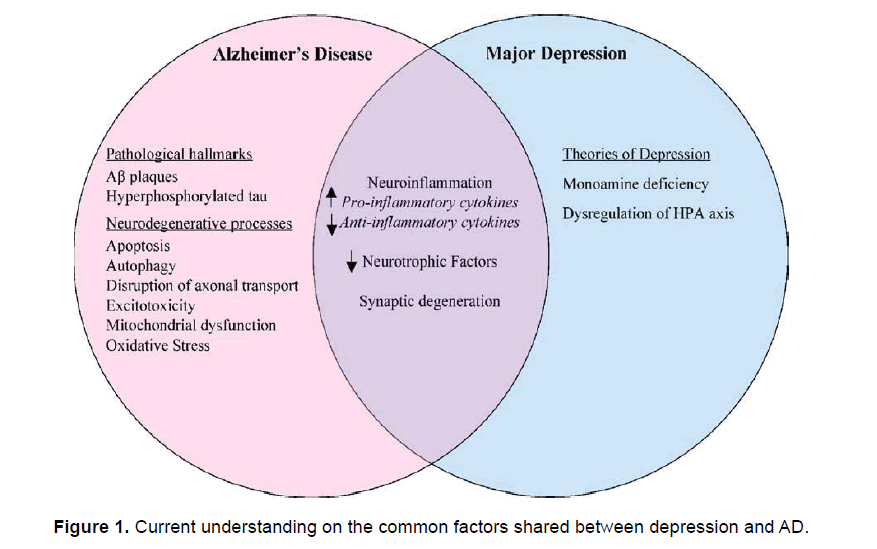

Antidepressants targeting the monoamines have been studied as potential remedies for AD. AD and depression, including inflammatory processes, reduced neurotrophic factors, and altered neuronal plasticity. The shared neuropathological processes provide substantial evidence to support intimate relationship between AD and depression (Figure 1) (Amieva et al., 2008).

Symptoms of Depression

Experts estimate that up to 40 percent of people with Alzheimer's disease suffer from significant depression. The common symptoms shared by both psychological diseases are apathy, Loss of interest in activities and hobbies, social withdrawal and Isolation, Trouble concentrating. In addition, the cognitive impairment experienced by people with Alzheimer's often makes it difficult for them to articulate their sadness, hopelessness, guilt and other feelings associated with depression. Depression in Alzheimer's doesn't always look like depression in people without Alzheimer's. Here are some ways that depression in a person with Alzheimer's may be different:

- May be less severe

- May not last as long and symptoms may come and go

Precaution to be Taken

The person with Alzheimer's may be less likely to talk about or attempt suicide as a caregiver, if you see signs of depression, discuss them with the primary doctor of the person with dementia. Proper diagnosis and treatment can improve sense of well-being and function.

Diagnosing Depression with Alzheimer's Disease

There is no single test or questionnaire to detect depression. Diagnosis requires a thorough evaluation by a medical professional, especially since side effects of medications and some medical conditions can produce similar symptoms.

An evaluation for depression will include:

- A review of the person's medical history

- A physical and mental examination

- Interviews with family members who know the person well because of the complexities involved in diagnosing depression in someone with Alzheimer's, it may be helpful to consult a geriatric psychiatrist who specializes in recognizing and treating depression in older adults. Ask your doctor for a referral. (Amieva et al., 2008) (Amieva et al., 2008) (Bremmer et al., 2009)

The National Institute of Mental Health established a formal set of guidelines for diagnosing the depression in people with Alzheimer's. Although the criteria are similar to general diagnostic standards for major depression, they reduce emphasis on verbal expression and include irritability and social isolation. For a person to be diagnosed with depression in Alzheimer's, he or she must have either depressed mood (sad, hopeless, discouraged or tearful) or decreased pleasure in usual activities, along with two or more of the following symptoms for two weeks or longer:

- Social isolation or withdrawal

- Disruption in appetite that is not related to another medical condition

- Disruption in sleep

- Agitation or slowed behaviour

- Irritability

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feelings of worthlessness or hopelessness, or inappropriate or excessive guilt

- Recurrent thoughts of death, suicide plans or a suicide attempt (Bachurin et al., 2001).

Treating Depression

Getting appropriate treatment for depression can significantly improve quality of life.

The most common treatment for depression in Alzheimer's involves a combination of medicine, counselling, and gradual reconnection to activities and people that bring happiness. Simply telling the person with Alzheimer's to "cheer up," "snap out of it" or "try harder" is seldom helpful. Depressed people with or without Alzheimer's are rarely able to make them better by sheer will, or without lots of support, reassurance and professional help.

Map out a plan to approach Alzheimer's- There are many questions you'll need to answer as you plan for the future. Use Alzheimer's Navigator — our free online tool — to guide you as you map out your plan. (Bamberger et al., 2003)

Go to Alzheimer's Navigator

Non-Drug Approaches

- Support groups can be very helpful, particularly an early-stage group for people with Alzheimer's who are aware of their diagnosis and prefer to take an active role in seeking help or helping others; counselling is also an option, especially for those who aren't comfortable in groups

- Schedule a predictable daily routine, taking advantage of the person's best time of day to undertake difficult tasks, such as bathing

- Make a list of activities, people or places that the person enjoys and schedule these things more frequently

- Help the person exercise regularly, particularly in the morning

- Acknowledge the person's frustration or sadness, while continuing to express hope that he or she will feel better soon

- Celebrate small successes and occasions

- Find ways that the person can contribute to family life and be sure to recognize his or her contributions

- Provide reassurance that the person is loved, respected and appreciated as part of the family, and not just for what she or he can do now

- Nurture the person with offers of favourite foods or soothing or inspirational activities

- Reassure the person that he or she will not be abandoned

Medication to Treat Depression In Alzheimer's

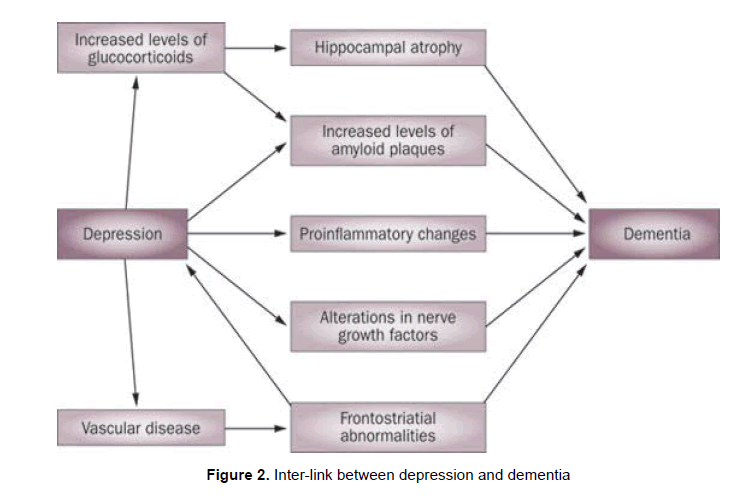

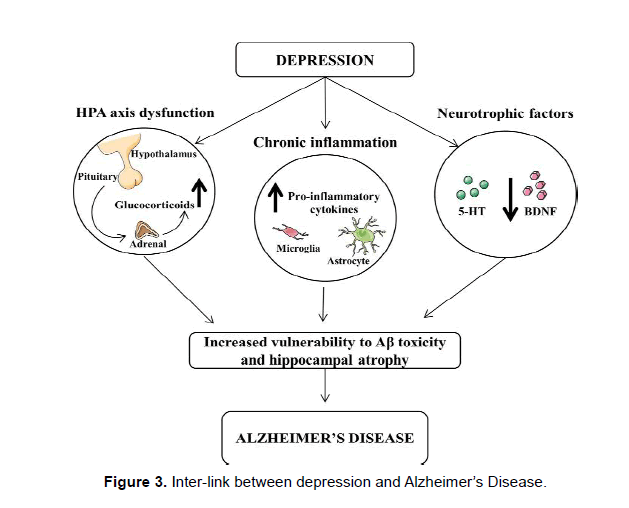

There are several types of antidepressants available to treat depression. Antidepressants called Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) are often used for people with Alzheimer's and depression because they have a lower risk than some other antidepressants of causing interactions with other medications Figure 2 & 3.

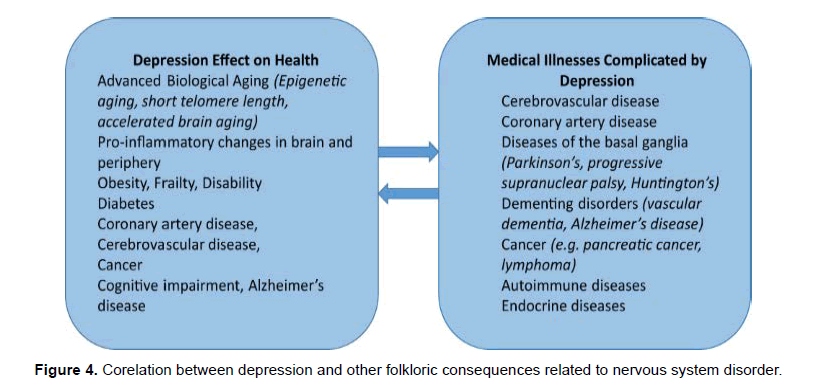

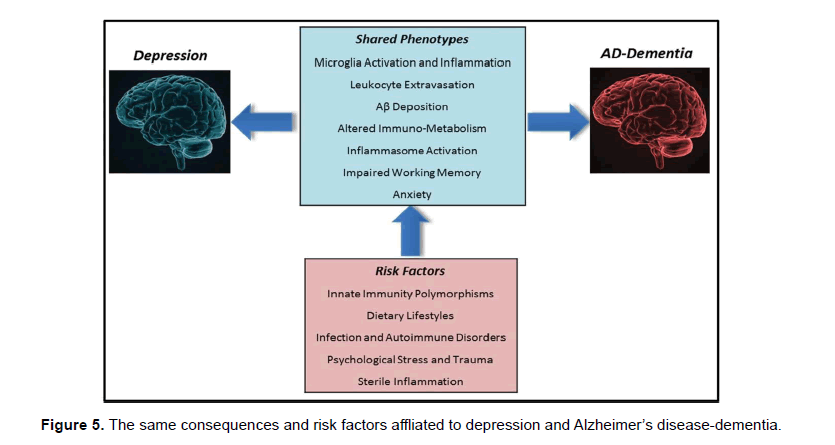

As with any medication, make sure to ask about risks and benefits, as well as what type of monitoring and follow-up will be needed (Bayer et al., 2005) (Billings et al., 2005) (Bremmer BW et al., 2009) Figure 4 & 5.

Flow chart shows: Inter-link between depression and dementia: Figure 2.

Conclusion

In addition to cognitive symptoms, a significant portion of AD patients suffer from depression. Depression has been demonstrated to be a risk factor for AD and suggested to be a possible prodrome for AD. Several common neurodegenerative mechanisms underlie the development of AD and depression, including inflammatory processes, reduced neurotrophic factors, and altered neuronal plasticity. The shared neuropathological processes provide substantial evidence to support intimate relationship between AD and depression. The possibility that depression may lead to neurological disorders does not confine to AD, but could extend to other dementias, PD, and stroke.

Thus far, there is no definitive evidence to associate depression with AD, and the underlying mechanisms regarding the links between depression and neurodegenerative diseases have not been elucidated. Owing to the highly prevalent and devastating natures of these disorders, future research is warranted in order to provide further insights toward the possible existence of pathophysiological associations between these neuropsychiatric conditions.

References

- Alexolioulos, G.S., Meyers, B.S., Young, R.C., Camlibell, S., Silbersweig, D., Charlson, M., (1997). ‘Vascular deliression’ hyliothesis. Arch. Gen. lisychiatry 54, 915–922.

- Alonso, R., Griebel, G., liavone, G., Stemmelin, J., Le Fur, G., Soubrie, li. (2004). Blockade of CRF(1) or V(1b) recelitors reverses stress-induced suliliression of neurogenesis in a mouse model of deliression. Mol. lisychiatry 9, 278–286 224.

- Amieva, H., Le Goff, M., Millet, X., Orgogozo, J.M., lieres, K., Barberger-Gateau, li., Jacqmin-Gadda, H., Dartigues, J.F. (2008). lirodromal Alzheimer’s disease: successive emergence of the clinical symlitoms. Ann. Neurol. 64, 492–498.

- Bachurin, S., Bukatina, E., Lermontova, N., Tkachenko, S., Afanasiev, A., Grigoriev, V., Grigorieva, I., Ivanov, Y., Sablin, S., Zefirov, N., (2001). Antihistamine agent Dimebon as a novel neurolirotector and a cognition enhancer. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 939, 425–435.

- Bamberger, M.E., Harris, M.E., McDonald, D.R., Husemann, J., Landreth, G.E., (2003). A cell surface recelitor comlilex for fibrillar beta-amyloid mediates microglial activation. J. Neurosci. 23, 2665–2674.

- Bayer, A.J., Bullock, R., Jones, R.W., Wilkinson, D., liaterson, K.R., Jenkins, L., Millais, S.B., Donoghue, S., (2005). Evaluation of the safety and immunogenicity of synthetic Abeta42 (AN1792) in liatients with AD. Neurology 64, 94–101.

- Billings, L.M., Oddo, S., Green, K.N., McGaugh, J.L., LaFerla, F.M., (2005). Intraneuronal Abeta causes the onset of early Alzheimer’s disease-related cognitive deficits in transgenic mice. Neuron 45, 675–688.

- Bremmer, M.A., Deeg, D.J., Beekman, A.T., lienninx, B.W., Lilis, li., Hoogendijk, W.J., (2007). Major deliression in late life is associated with both hylio- and hyliercortisolemia. Biol. lisychiatry 62, 479–486

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 3348

- [From(publication date): 0-2021 - Apr 25, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 2662

- PDF downloads: 686