Conservation Challenges of Omo National Park from National Park Governance and Management Perspectives in South Omo Zone, Ethiopia

Received: 03-Jul-2023 / Manuscript No. jee-23-103505 / Editor assigned: 05-Jul-2023 / PreQC No. jee-23-103505 (PQ) / Reviewed: 19-Jul-2023 / QC No. jee-23-103505 / Revised: 22-Jul-2023 / Manuscript No. jee-23-103505 (R) / Published Date: 29-Jul-2023 DOI: 10.4172/2157-7625.1000415

Abstract

A key component of international conservation strategy is the creation of protected areas. Ethiopia is one of the countries from east Africa which recognized protected area to conserve its unique fauna and flora. The country includes a wide range of ecosystems, including semi-arid, open grassland steppe, and arid desert, all of which have a high potential for biodiversity and endemism. To protect its unique species, Ethiopia created a number of national parks, sanctuaries, wildlife reserves, and restricted hunting areas. The main issues facing protected areas in the country, however, are a lack of clear national and international policies, a lack of commitment from national park governance, a lack of funding, and the need for education to increase public awareness. As a result, this study’s focus was on the conservation challenges facing Ethiopia’s Omo National Park from the perspectives of governance and management. In this regard, the park management officers and wardens in the south omo zone Jinka town provided the primary data. Several written materials from the official records of Omo National Park also provided some secondary data. Omo National Park is managed by the Southern Nations, Nationalities and People’s Regional State Culture and Tourism Bureau Hawassa, according to informants and review findings from EUCAbased sources. The Park has a management staff and a security team, in the respondents’ opinion. The security staff may have the ability to make decisions regarding park-related matters, and they have the responsibility and power to oversee the management structures. The national park is largely invaded by local pastoralists with a large number of cows, and the local inhabitants hunt extensively inside the park. South Sudanese Murule tribes and even the park security personnel engage in illicit hunting. Only the influences of the park’s security teams and park wardens are visible when looking closely at the park. Lack of effective low enforcement has caused a huge extinction of elephants as a result of unauthorized labor taken up by both locals and visitors. The major causes of conflict between ethnic pastoralists and wildlife in the Omo National Park area are a lack of clearly defined boundaries and locally based wildlife lows. As a result, the park’s potential ecological quality and diversity are currently declining, so that urgent conservation efforts as well as suitable management and governance measures highly needed.

Keywords

Conservation challenge; National park governance; Protected areas

Introduction

The creation of protected areas (PAs) is a key component of international conservation initiatives, according to Dearden P [1]. A protected area is described as “clearly defined geographic space, recognized, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values. PAs can offer many ecological services in addition to preserving biodiversity [2]. They can help manage risks to PAs, such as the management of invasive plant and animal species, and lower resource utilization levels from PAs such deforestation in terrestrial biomes [3].

Big mammalian herbivores are abundant and diverse in East Africa. Ethiopia has a wide range of environments, including arid deserts, open grassland steppes, semi-arid savannas, highland forests, and afro-alpine moor lands, which support a variety of animal and plant species [4].According to Jacobs and, Ethiopia is one of the few countries in the world to have a unique biota with a high level of endemism [5].

However, both the quantity and distribution of its wildlife population and forest have decreased over the previous century. As a result, protected areas are viewed as the foundation for safeguarding natural resources. Fortunately, Ethiopia is one of the countries with protected areas recognized to preserve its distinctive flora and fauna [6]. To preserve its unique species, it established a variety of national parks, sanctuaries, wildlife reserves, and restricted hunting areas [7].

However, the federal government was given back control of the National Park’s management under the EWCA because there were no discernible negative consequences on the preservation and sustainable use of PAs [8]. Despite the country’s abundance in plant and animal species, some of which are indigenous, the previous conservation strategy proved ineffective in preventing the decline and extinction of the wildlife and its natural ecosystems. These led to an increase in the number of plant and animal species on the list of threatened and endangered species as well as significant habitat alterations, according to Michael J. Jacobs and Catherine A Schloeder [9].

The other issues facing protected areas in the country include unclear national and international rules, a lack of commitment from government agencies, a lack of funding, and the need for education to increase public awareness [10]. The ethnic groups of The Mursi, Suri, Nyangatom, Dizi, and Me’en have been posing conservation issues in Omo National Park, among others, due to the surrounding human activity within the park.

The other issues facing protected areas in the country include unclear national and international rules, a lack of commitment from government agencies, a lack of funding, and the need for education to increase public awareness [10]. The ethnic groups of The Mursi, Suri, Nyangatom, Dizi, and Me’en have been posing conservation issues in Omo National Park, among others, due to the surrounding human activity within the park.

Pastoralists and their herds are encroaching on every area of the park. Previous research done in ONP revealed that, Dassenetch and other pastoral groups have traditionally engaged in conflict with the pastoral neighbors, the Benna, Ari, and Hamer societies, over the grazing of their animals [11]. Furthermore, Yirssaw Demeke and Afework Bekele noted in 2000 that human activities in the villages of Kure, Maki, Bongso, Mugji, and Lebuk have deteriorated the wildlife’s favorable habitats in the ONP.

The protected area’s fauna can harm pastoralists as well. However, there hasn’t been any current research on the region’s conservation issues from the standpoint of its management and governance. Therefore, the focus of this study is on the conservation challenges of Omo National Park from the perspectives of governance and management in South Omo Zone’s Ethiopia’s.

Methodology

Description of the study area

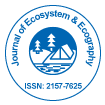

Location of the area: The research was carried out in the Omo National Park (ONP), a protected area in the southern nationalities and peoples region of Ethiopian. Among Ethiopia’s protected places, ONP is one that is scenic. This spectacular National Park is located 870 kilometers to the southwest of Addis Abeba, near to the borders with Kenya and Sudan. South Omo and Bench Maji are the two administrative zones where ONP is located. It is bordered on the east by the Omo River, on the north and west by the Maji Mountains’ foothills, and on the south by the Neruth River. Geographically, the study area are located between the latitudes 5o29’ and 6o35’N and 35o33’ and 35o56’E. This national park recently had a total area of 3566 square kilometers. The Nyangatom woreds in the south, the Surima woreda in the north, the Mursi (Hana) woreda in the east, the Mui River in the north, and the Omo River in the south-east all serve as boundaries for this national park (Figure 1).

Climate: The climate of OMN is semi-arid with high mean annual temperature and solar radiation [12]. The mean annual temperature varies from 24 to 38°C. The annual rainfall recorded was 830 mm. There are two well separated rainy seasons: heavy rain from March to April and light rain from August to September.

Vegetation: Fifty percent of the area is bush and the rest is forest, savanna bush land, savanna grassland and open grassland [12].

Fauna: The Park supports a typical bush savanna fauna with 81 mammals including bats, rodents and 237 species of birds. The most common and noticeable mammalian species are African elephant, buffalo, lesser-kudu, greater-kudu, duiker, warthog, tiang, Lewel’s hartebeest, Oryx, Grant’s gazelle, gerenuk, giraffe, cheetah, wild dog, lions, leopards, gureza, common baboon and vervet monkeys.

The Surrounding Community: Omo national park area is also very well-known for its rich cultural diversity, where many elements of the earliest nomadic lifestyles or cattle movement are still continued. Hammer, Benna, Mursi, Ngagatom, Ari, Karo, Body, Kwegu are communities very well known for their traditional culture, lifestyles, colorful body decoration, ceremonies, festivals, rituals, and other living.

Research design

Only qualitative research design was employed for this study to slightly achieve the intended objective.

Data Source: This study largely focused on the conservation challenges of Omo National Park from the management and governance perspectives. Additionally, the main data was gathered through park wardens and administrative staff. Some secondary information was gathered from a number of written records from the Omo National Park administration office, which are located in Jinka, the regional center of the south Omo zone. Due to a lack of time, accessibility, and other factors, the park administrators could only be reached via phone and Gmail to get the data. Household surveys and focus groups discussion were not conducted as part of the study since the proximity and financial limitation were taken into consideration.

Methods of Data Collection: Selected informants who have indepth knowledge of the overall park administration and governance concerns participated in in-depth key informant interviews. The park wardens and managers grouped the main threats, such as cattle grazing, tree cutting, poaching, and charcoal production from office records. Additionally, through secondary data collection techniques, it was possible to obtain seminar papers, conference proceedings, earlier master’s theses and PhD dissertations, socioeconomic studies, park-related studies, statistical publications and maps, and all relevant documents and project reports incorporated in this research.

Data Analysis: The analysis technique was covered in terms of readily available non-quantifiable data (information from open-ended questions, key informant interviews) through qualitative description and narration.

Result and discussion

The researcher obtained all the data from the Omo National Park’s head office in Jinka town in order to complete this study. It was acquired through direct telephone contact and text message inquiries about official park management records. In response to challenges, the responder attempted to illustrate on the state and structure of national park governance and management. The respondents list the following challenges as obstacles for Omo National Park.

Lack of community participation

It has been stated that the Mursi, Suri, Nyangatom, Dizi, and Me’en are in danger of being displaced and/or denied access to their customary grazing and farming lands. Accordingly, Degu Tadie and Anke Fischer, 2023 stated that there were no specified user rights for pasture in lower Omo Ethiopia because; access to grazing was typically non-exclusive among both tribes, Hamar and Bashada.

Conflict among park management and a burden on wildlife have come from partial or total denial and limitation. Similar to this, Myers and Cashdan stated that access to practically all resources around protected areas should never be limited because doing could lead to territorial and social border defense expressions both inside and beyond the protected region [13,14]. The park manager added that the Omo people risk becoming illegal squatters on their property as a result of the drawing of the park boundaries in November 2005 and the recent management takeover of the park by African Parks. There are rumors that park authorities forced these tribal members to sign paperwork they couldn’t read.

According to the information provided by our respondent, African Parks declared in October 2008 that they were handing up control of Ethiopia’s Omo National Park and departing the country. According to AP, ‘the irresponsible manner of living of some of the ethnic groups’ is incompatible with the sustainable administration of Ethiopia’s parks. The group has to deal with the native population’s attempts to maintain their traditional way of life within the park’s boundaries.

Lack of appropriate low enforcement and implementation

According to the park wardens and zonal conservation authorities, the elephant population has been drastically reduced because of the unlawful extraction by both locals and tourists. Similarly, Mengist W claimed that illegal hunting poses a threat to efforts to conserve wildlife in Africa and is a widespread practice in Ethiopia [15].

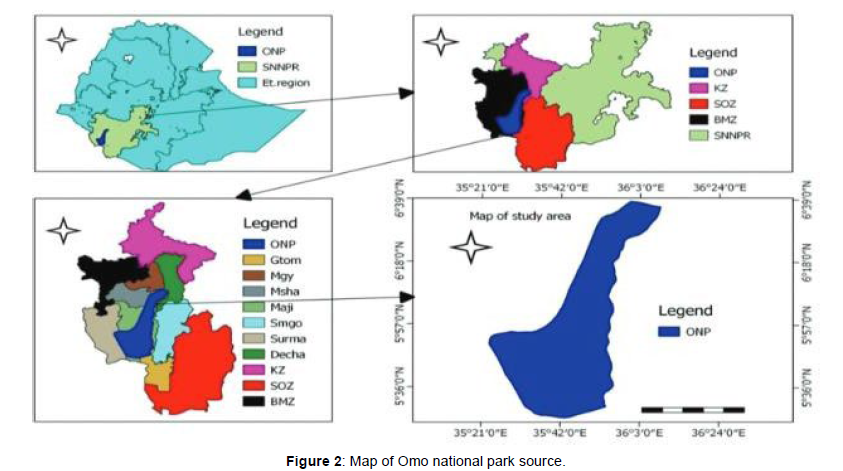

According to information from park wardens, The primary obstacle and challenge for the protection of the most significant species in the park is the absence of a clear boundary separating the national park from its resident pastoralist.in the informants’ opinion, lack of clearly defined boundaries and locally based wildlife lows are the main causes of conflict between ethnic pastoralists and wildlife’s. Similar to this, the Regulation No. 163/2008 regulating the protected areas in Art 3 stated about the Boundaries of Wildlife Conservation Areas defined the protected areas managed by EWCA. Based on the aforementioned article, the Federal and regional governments decide to redraw the boundaries of national parks, wildlife reserves, sanctuaries, controlled hunting areas, and community conservation areas, protection, and utilization areas in order to improve management (Figure 2).

The governance status and structure of Omo National park

The governance structure of Omo National park: The researcher attempted to gather information on the above-selected title by direct phone calls, and tried to make the information clear to the questioners. The manager began by outlining the site, the general goal environment, the species kinds, and the priority species for the creation of the Omo national park.

The rare African elephant is the Omo National Park’s top priority species, but later it also protected the endangered African wild dog, lelwel hartebeest, and other large ungulates of the savannah. The southern nation’s nations and people’s regional state culture and tourism office, as well as EWUCA, both oversee the park. However, our respondents clarified that management of the park is now solely done at the level of the park office in the south omo zone and is now separated from the above regional state office at the zonal level.

Respondents added that the follow-up at the EWCA level is currently completely weak and ignored because of the degree of capital. A management staff and a security team are present in The Park, in the opinion of the respondents. Even if they are truly engaged in unlawful hunting, the security staff has the potential to make decisions on park issues.

The key informant also stated that only park wardens and security personnel could see the park in close look. Contrarily, according to Mengist W (2020), most of the PAs in Ethiopia were transferred from the Federal Bureau of Wildlife Conservation in 1995 based on the concept of decentralization on natural resource management (Nishizaki Nobuko (2014). The information also criticized how weak and perhaps illusory the management mandate is above the zone official level.

The governance status of Omo national park: According to the informants and secondary data from EUCA, the Southern Nations, Nationalities and People’s Regional State Culture and Tourism Bureau in Hawassa, by EWCA and regional protected areas administrations, and in certain cases communities, jointly manage Omo National Park. The local community views the park as communal pastoral grazing land rather than a protected region, according to information. we obtained from the park warden and the zonal head officer of the Omo national park. This led to the herds completely encroaching on the local pastoralists, and the nearby indigenous tribes are claiming ownership of the land.

Conclusion and recommendation

In comparison to other east African countries, Ethiopia is known for having a high biodiversity. Additionally, the government created a number of national parks and other protected areas among its several regional states. Additionally, it has a few national park governance systems that fall within its local and global standards. Most of Ethiopia’s national parks are currently facing significant challenges from a variety of angles. Limited national park governance situations are one of the main obstacles to maintaining the national park. The unique African elephant is being threatened by various factors, including poaching, environmental deterioration, conflicts between people and animals, and others. Omo National Park is a beautiful protected area intended to safeguard them.

Ethiopia is known as one of the countries with the greatest biodiversity in east Africa, and the absence of effective local and national government presents another obstacle to the conservation of the park. In a similar vein despite the fact that it is governed by a shared federal-regional state government, the Omo National Park is only managed by a small number of regional organizations. Conflict over the protected area has arisen as a result of the weak governance among different ethnic groups. According to the results of this study, the claims of belongingness among the ethnic communities bordering the park had never been resolved. Even the park guards themselves engage in unlawful hunting among the illegal gangs.

According to the park officers and the Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority, the boundary lines of Omo National Park are not clearly marked. This has made the local conservation problem more complicated. The following solution is therefore considered to be important for having sound efficient protected area governance in Omo National Park based on the aforementioned shortcomings.

For simple management and conservation, a national park should have precisely defined boundaries.

It is important to respect and serve the local pastoral community’s needs and interests.

The governance status and structure of Omo National park

The governance structure of Omo National park: The researcher attempted to gather information on the above-selected title by direct phone calls, and tried to make the information clear to the questioners. The manager began by outlining the site, the general goal environment, the species kinds, and the priority species for the creation of the Omo national park.

The rare African elephant is the Omo National Park’s top priority species, but later it also protected the endangered African wild dog, lelwel hartebeest, and other large ungulates of the savannah. The southern nation’s nations and people’s regional state culture and tourism office, as well as EWUCA, both oversee the park. However, our respondents clarified that management of the park is now solely done at the level of the park office in the south omo zone and is now separated from the above regional state office at the zonal level.

Respondents added that the follow-up at the EWCA level is currently completely weak and ignored because of the degree of capital. A management staff and a security team are present in The Park, in the opinion of the respondents. Even if they are truly engaged in unlawful hunting, the security staff has the potential to make decisions on park issues.

The key informant also stated that only park wardens and security personnel could see the park in close look. Contrarily, according to Mengist W (2020), most of the PAs in Ethiopia were transferred from the Federal Bureau of Wildlife Conservation in 1995 based on the concept of decentralization on natural resource management (Nishizaki Nobuko (2014). The information also criticized how weak and perhaps illusory the management mandate is above the zone official level.

The governance status of Omo national park: According to the informants and secondary data from EUCA, the Southern Nations, Nationalities and People’s Regional State Culture and Tourism Bureau in Hawassa, by EWCA and regional protected areas administrations, and in certain cases communities, jointly manage Omo National Park. The local community views the park as communal pastoral grazing land rather than a protected region, according to information. we obtained from the park warden and the zonal head officer of the Omo national park. This led to the herds completely encroaching on the local pastoralists, and the nearby indigenous tribes are claiming ownership of the land.

Conclusion and recommendation

In comparison to other east African countries, Ethiopia is known for having a high biodiversity. Additionally, the government created a number of national parks and other protected areas among its several regional states. Additionally, it has a few national park governance systems that fall within its local and global standards. Most of Ethiopia’s national parks are currently facing significant challenges from a variety of angles. Limited national park governance situations are one of the main obstacles to maintaining the national park. The unique African elephant is being threatened by various factors, including poaching, environmental deterioration, conflicts between people and animals, and others. Omo National Park is a beautiful protected area intended to safeguard them.

Ethiopia is known as one of the countries with the greatest biodiversity in east Africa, and the absence of effective local and national government presents another obstacle to the conservation of the park. In a similar vein despite the fact that it is governed by a shared federal-regional state government, the Omo National Park is only managed by a small number of regional organizations. Conflict over the protected area has arisen as a result of the weak governance among different ethnic groups. According to the results of this study, the claims of belongingness among the ethnic communities bordering the park had never been resolved. Even the park guards themselves engage in unlawful hunting among the illegal gangs.

According to the park officers and the Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority, the boundary lines of Omo National Park are not clearly marked. This has made the local conservation problem more complicated. The following solution is therefore considered to be important for having sound efficient protected area governance in Omo National Park based on the aforementioned shortcomings.

For simple management and conservation, a national park should have precisely defined boundaries.

It is important to respect and serve the local pastoral community’s needs and interests.

References

- Dearden P, Bennett M, Johnston J (2005) Trends in global protected area governance, 1992- 2002. Environmental Management 36: 89-100.

- Darren JB, Thomas AC, Lenore F (1998) Habitat loss and population decline: A meta-analysis of the patch size effect. Ecology 79: 517-533.

- Kutilek M J (1979) Forage-Habitat Relations of non-migratory African Ungulates in Response to Seasonal Rainfall. Journal of Wildlife Management. 43: 899-908.

- Jacobs M J and Schloeder C A (2001) Impacts of Conflict on Biodiversity and Protected Areas in Ethiopia. Biodiversity Support Program (World Wildlife Fund), Washington.

- World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC) (1991) Global Biodiversity: Status of the Earth's Living Resources. Chapman and Hall, London.

- Desalegn Wana (2004) Strategies for Sustainable Management of Biodiversity in the Nechsar National Park, Southern Ethiopia. A Research Report Submitted to OSSREA: Addis Ababa.

- Council of Ministers (2008) Council of ministers regulations to provide for wildlife development, conservation and utilization. Council of Ministers Regulation No 163/2008, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 4567-4600.

- Almaz Tadesse (1996) Nature conservation and indigenous people approaches in conflict resolution. Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Department Addis Ababa.

- Samuel Tefera (2014) Changes in Livestock Mobility and Grazing Pattern among the Hamer in Southwestern Ethiopia. African Study Monographs Suppl 48: 99-112.

- Stephenson J.and Mizuno A (1978) Recommendation on the conservations of wildlife in the Omo-Tama-Mago Rift Valley of Ethiopia. EWCA, Addis Ababa: mimeo.

- Degu Tadie and Anke Fischer (2023) Natural resource governance in lower Omo, Ethiopia – negotiation processes instead of property rights and rules? International Journal of the Commons.

- Myers F(1982) Always ask: Resource use and Land Ownership among Pintupi Aborigines of the Australian Western Desert. American Association for the Advancement of Science Selected Symposium 67, Boulder Colorado, USA: Westview Press.

- Cashdan EA, Barnard MC, Bicchieri CA, Bishop V, Blundell J (1983) Territoriality among Human Foragers; Ecological Models and an Application to Four Bushman Groups. Current Anthropology 24: 47-66.

- Mengist W (2020) Challenges of Protected Area Management and Conservation Strategies in Ethiopia: A Review Paper. Adv Environ Stud 4:277-285.

- Nishizaki Nobuko (2014) Neoliberal conservation in Ethiopia: An analysis of current conflicts in and around protected areas and their resolution. African Study Monographs Suppl 50: 191- 205.

Indexed at, Google Scholar , Crossref

Citation: Inada D (2023) Conservation Challenges of Omo National Park from National Park Governance and Management Perspectives in South Omo Zone, Ethiopia. J Ecosys Ecograph 13: 415. DOI: 10.4172/2157-7625.1000415

Copyright: © 2023 Inada D. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 1849

- [From(publication date): 0-2023 - Apr 25, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1431

- PDF downloads: 418