Review Article Open Access

Comparative Study of Regulating the Moral Harassment: Lessons for China

Kai Liu*Faculty of Law, Economics and Governance, Utrecht University, The Netherlands

- *Corresponding Author:

- Kai Liu, Faculty of Law

Economics and Governance

Utrecht University

The Netherlands

Tel: +31-628514077

E-mail: k.liu@uu.nl

Received date: August 14, 2015; Accepted date: August 24, 2015; Published date: August 31, 2015

Citation: Liu K (2015) Comparative Study of Regulating the Moral Harassment: Lessons for China. Occup Med Health Aff 3:214. doi: 10.4172/2329-6879.1000214

Copyright: © 2015 Liu K. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Occupational Medicine & Health Affairs

Abstract

Moral harassment in the workplace is increasingly recognized as a stressor with serious consequences for employees and organizations alike. The work environment can influence people’s exposure to moral harassment. Through the comparative study of the Chinese legal regime and the European legal regime, namely, through comparing legal systems vis-à-vis preventing moral harassment at the workplace, t China can learn from the EU by including psychological risks in the occupational hazards, stipulating moral harassment as more comprehensive concept include its complete content in the legal text, and to adopting ‘soft laws’ in order to complement the statutory laws.

Keywords

Moral harassment; Occupational hazards; Legislation

Introduction

Moral harassment is one of the most rapidly emerging workplace violence complaints. Although there is no internationally accepted definition of moral harassment, it may be understood generally as repeated, non-physical acts of harassment at the workplace, occurring over a significant time period, that have a humiliating effect on the victim [1]. Moral harassment is due to unacceptable behaviour by one or more individuals and can take many different forms. It refers to intimidating, humiliating or embarrassing, harmful or unwanted conduct occurring in the context of an employment relationship that objectively violates the fundamental rights of the worker, namely his dignity, physical and moral integrity [2]. A similar concept which is often confusing with moral harassment is work stress. Indeed, it is difficult sometimes for the workers to distinguish moral harassment from the stress resulting from the work organization [3]. What makes the issue more complex is work stress could be in many cases regarded as a psychological outcome of moral harassment, resulting in occupational health problems [4]. Moral harassment is distinguished from work stress due to the fact that moral harassment is caused by a third party at workplace while work stress is caused in most cases by working load. Moral harassment is a problem troubling the workers’ occupational health. In December 2000, the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions reported that around eight percent of EU workers, or twelve million people, had been victimized by moral harassment during a twelve-month period [5].

In recent years, considerable progress has been achieved in the EU in recognizing the relevance of work-related stress in particular, and of psychosocial issues in general. This is due first to legal and institutional developments, in particular the 1989 Framework Directive on Health and Safety and the subsequent adaptation of legal frameworks in member states, second the development of infrastructures, the initiation of campaigns and initiatives on work-related stress [6]. In the academia, however, several academic disciplines have investigated moral harassment in the workplace (psychology, medicine, sociology, etc.), but legal theorists have lagged behind, despite the importance of this phenomenon [7]. Moreover, there is until the day of writing no research exploring the compressions of the EU system and the Chinese system in this field. As a legal research, this article is mainly focused on the legal aspects of the EU’s progress in comparing with the Chinese progress.

The Chinese law in the field of preventing moral harassment

According to some well-known Chinese scholars, moral harassment at the workplace means that the workplace parties, including for example, employers, administrative superiors, colleagues, subordinates, customers or other partners in the recruitment or work place take use of unpleased behaviours in form of both words and deeds against the employee concerned, which lead to the latter feel like being humiliated or being in an unbearable hostile environment [8-10]. It has also reached a common opinion that that have negative psychological and physical effects on the target.

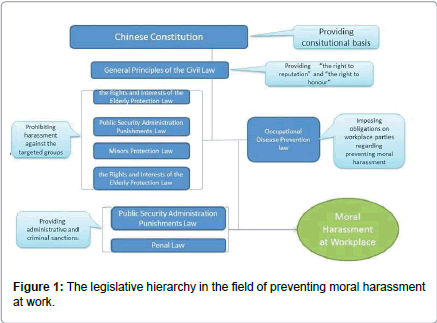

Legislative framework: The Chinese Constitution provides, in its Article 38, stipulates that the personal dignity of citizens of the People’s Republic of China is inviolable. Insult, libel, false accusation or false incrimination directed against citizens by any means is prohibited [11]. According to the mainstream viewpoint in Chinese legal academia, this provision, in effect, presents the constitutional basis for preventing moral harassment at workplace for the reason that moral harassment falls within the provided “insult” [12]. Furthermore General Principles of the Civil Law stipulates, in its Article 101 and Article 120 that citizens have “the right to reputation and the right to honor”. The personality of citizens shall be protected by law, and the use of insults, libel or other means to damage the reputation of citizens or legal persons shall be prohibited. The law prohibits unlawfully divesting individual citizens and legal persons of their honorary titles [13]. Nevertheless, the workplace moral harassment prevention has been one of the focuses in the law-making activity in China since not long ago. It was until June 26, 2005 when the draft of Women's Rights Protection Law (WRPL) amendment was submitted to the national legislature, moral harassment, which was of great concern in the society but had been for decades not receiving sufficient attention on the part of the state, for the first time entered the Chinese legislative agenda [14]. In this sense, it could say, in around one decade development, the Chinese moral harassment law grew from almost nothing into the present legal system.

WRPL prohibits, it’s Article 40, sexual harassment against woman and expressly states that the victims have the right to lodge complaint to unit or organ concerned [15]. In case of a violation which result in sexual harassment to a woman, and constitutes a violation of public order of administration, the victim can ask the police institutions to impose administrative punishment, and also bring civil litigation to court [16]. This latter provision effectively sets a legal link between the legal responsibilities arising from sexual harassment in the WRPL with Public Security Administration Punishments Law (PSAPL), bringing feasibilities to the provisions’ implementation. After that, through amendment to the existing laws, many laws became relevant in the field of moral harassment prevention, and as such are included in the legal system in this field. These laws are as follows: the mentioned above PSAPL, the Minors Protection Law, the Rights and Interests of the Elderly Protection Law (RIEPL), and the Penal Law. In addition, China has adopted two OHS laws, namely, the Work Safety Law and the Occupational Diseases Prevention Law (ODPL). The latter set up obligations on the part of employers regarding preventing moral harassment at workplace.

In the legislative hierarchy, WRPL, RIEPL and the Minors Protection Law jointly prohibit harassment against the targeted groups, namely, women; elderly people and the minors, while the PSAPL and the Penal Law are focused on imposing administrative and criminal sanction on the persons are in violation. In order to help readers to conceptualize the issues more clearly, there is below Figure 1 provided.

From the description of the legislative framework, it could be noted that until the day of writing, a special law focused on preventing the prevention of moral harassment is not adopted neither is put on the legislature’s law-making agenda. Once an incident of workplace harassment becomes a lawsuit, the court makes legal decisions based on the above laws. Although it is arguable that judges tend to consider the workplace elements in deciding workplace moral harassment, failing to adopt a special law against moral harassment at workplace lead to that the entire justice system misperceives the workplace moral harassment issues with general moral harassment issues.

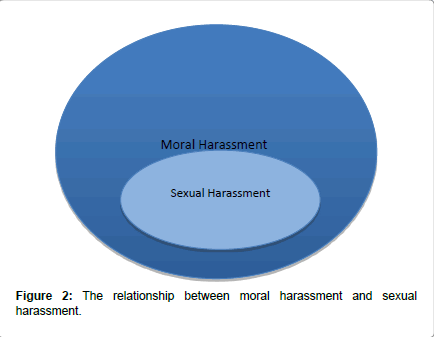

For this reason, exclusively stipulating the sexual harassment in legislations has the danger of leaving the rest of moral harassment being not subject of laws (Figure 2).

Basic concepts of moral harassment at work: In the legislative framework is that sexual harassment (xing sao rao) is expressly stipulated instead of a comparatively more general concept, i.e., the moral harassment (qi fu), for example, the above-mentioned WRPL where stipulates exclusively the prevention against sexual harassment.

Indeed, sexual harassment represents a serious risk to employees' psychological and physical well-being [17] and the prevalence of such harassment in the workplace is now acknowledged to be widespread [18]. Yet, the sexual harassment possesses a comparatively narrower definition than moral harassment. In comparison, the moral harassment includes, in addition to sexual harassment, also interpersonal conflict harassment, and outcomes arising from other factors, such as a sudden change in work organization, job insecurity, poor relations between staff and the hierarchy, bad relations between colleagues, as such is a great threat to employees [19]. There is some evidence that moral harassment has more diverse negative job-related, psychological, and health effects on the workers who experience it than sexual harassment [20]. The below picture best describes the relationship between moral harassment and sexual harassment.

The personal scope and duties of the employers

Protecting worker’s psychological health: In setting up the workplace, the employer, should ensure the equipment, tools, apparatus and other facilities meet the requirements for protecting worker's physical and psychological health [21]. According to the Interpretation of ODPL, issued by the Chinese People’s Congress, the statutory requirement is for the purpose of preventing labor intensity from being overloaded, and avoiding excessive mental or psychological stress vis-à-vis the employees, by means of ensuring the production arrangement away from being unreasonable, and the working tools, utensils, equipment away from not meeting the requirements [21]. It should be noted that the law here fails to expressly state to prevent moral harassment.

Preventing sexual harassment:As earlier stated, WRPL prohibits sexual harassment against woman. Under this requirement, first in place, the employer is prohibited from conducting any sexual harassment towards female employees. However, it should be noted that from its wording, the law fails to mandate the employer the obligation to ensure the workplace free from sexual harassment. Nevertheless, combining the first employer’s obligation given by ODPL, i.e., to protect psychological health at workplace, it implicitly impose the duty on the employer to protect female workers from the sexual harassment, for the reason that exposure to sexual harassment would have, inter alia, negative psychological consequences vis-à-vis women in organizational settings, and their psychological health [22].

Ensuring minor worker from engaging in the position that could cause harm to his/her psychological health due to his/her age: For the purpose of prohibiting using child labor and exploitation, the minimum age for working in China is sixteen [23]. Meanwhile, according to the Minors Protection Law, citizens under the age of eighteen are all minors [24]. In this sense, employers may recruit minors above sixteen. However, due to the characteristics of minors as adolescents, such as in the demographic, behavior, belief, and social influence aspects, the law, as such, mandates that the employer that recruits minors over the age of sixteen but under eighteen shall not assign them to any overstrenuous, poisonous or harmful labour or any dangerous operation, and or to any position that could cause harm to their physical and psychological health [25].

Creating work environment conducive to psychological health: The Article 15 of the Mental Health Law imposes the obligation on the employers to create a work environment conducive to the physical and psychological health of employees, to pay attention to the psychological health of employees and, for employees in a specific period of career development or at specific positions, conduct targeted psychological health education [26]. It should be noted that, the same as the above previous provisions discussed, the law, again fails to expressly state moral harassment in its legal text.

law, trade unions are primary, if not all, representatives of workers in China, safeguarding the rights and interests of the workers [27]. And the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU) is the nationalised organisation federation in China, which is formally an organ of the Communist Party and is subordinate to its guidelines [28]. Generally, the trade unions shall oversee the prevention and control of occupational diseases and protect rights and interests of employees [29]. The trade union has a role to say when rules and regulations on the prevention and control of occupational diseases are formulated or amended, as employers shall solicit the opinions of trade unions. In this sense, the trade unions [30] should play a role, if the prevention moral harassment is part of the mandate on the employer to ensure a safe and healthy working environment. However, as stated before, the legal framework fails to address the moral harassment prevention, the legal basis for defining the role of trade unions could be only found in the general rules. According to scholars’ findings, the trade unions are, in practice, to some extent active in moral harassment matters, particularly in for example, workplace bullying. Largely, the trade unions function as intermediary party, trying to solve stressed relationships between bullying parties, rather than find out which party is the victim and defend the victim parties. In serious bullying cases, the trade unions might call police if the victim and the employer fail to do so [31]. Nonetheless, it should be mentioned that traditionally, the Chinese trade union is criticised for its non-adversarial character. The character refers to that in contrast to real representative bodies, the Chinese trade union in many cases tend to be conservative in defending the rights and interests of workers [32], given the fact that the subordination of the trade unions to the Party-state has not gone without question. In this context, failing to expressly stipulating moral harassment prevention in the legal text might justify the union’s keeping backward in this field.

Sanctions for a breach of the legislation: The sanctions in the field of preventing moral harassment at workplace is justified as an way of punishing the persons who are responsible for wrong doing and compelling parties at workplace be motivated by the threat of sanctions to comply laws. As earlier discussed, the legal basis on basis of which the Chinese legal systems impose sanctions on the wrongdoers in this field are found in the Penal Law as well as Public Security Administrative Punishments Law. According to women’s protection law, anyone who committed sexual harassment to a woman can be subject to sanctions by the police organ in the form of administrative punishment or be criminally prosecuted in the court of law [33]. The administrative punishment is carried out based on the Public Security Administration Punishments Law [34], in the forms of a. warning; b. pecuniary penalty; and c. administrative detention [35]. Similarly, all types of sexual harassment to a woman are sanctioned in the Chinese criminal law.

The EU laws in the field of preventing moral harassment

The importance of mental health at work is stated in the European Community Strategy for Health and Safety at Work (2007-2012): ‘problems associated with poor mental health constitute the fourth most frequent cause of incapacity for work’ [36]. This statement was made in 2007 and as such these are confirmed figures. Forecasts made by the World Health Organization worsen this situation by estimating that by 2020, depression will be the main cause of incapacity for work.

A detailed picture of the EU law

The legal basis for EU’s jurisdiction in preventing moral harassment at workplace: Article 31 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union provides the source for Community-wide action against moral harassment, stating that "every worker has the right to working conditions which respect his or her health, safety and dignity [37]. Article 118a.1 of the EC Treaty provides that “Member States shall pay particular attention to encouraging improvements, especially in the working environment, as regards the health and safety of workers” [38]. Through the particularly divisive interpretation of ‘working environment’ in the judgment of the Court of Justice, Case C-84/94, the Court considered that ‘working environment’ should be interpreted broadly, and that therefore the power conferred on the Council must also be broad. By making reference to international sources in order to back its argument on the concept of health and safety based on the Constitution of the World Health Organization, in whose preamble, health is defined as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing that does not consist only in the absence of illness or infirmity’, the court argues the working environment is supposed to include all the conditions that could affect the health and safety of workers within, and these factors could be physical or of any other kind [39]. In this sense, the “any other kind” should include moral harassment.

Directive 89/391: In the field of regulating moral harassment, the EU plays an increasingly significant role. Increasingly more and more policy documents, recommendations and directives have addressed important aspects of moral harassment, setting the scene for further developments in this area in EU countries [40]. One of the most is the Council Directive 89/391/EEC on the introduction of measures to encourage improvements in the safety and health of workers at work (also referred to as the Safety and Health Framework Directive) [41]. The Directive 89/391 established a general duty for employers to assess and prevent or reduce risks to safety and health at work. The current position of the European Commission is that moral harassment is covered under this directive. Indeed, under the terms of Article 6(1), employers are obliged to assess all the risks, including, inter alia, those related to chemical agents, work equipment and the design of workplaces. The list is not exhaustive and the national legislation enacted in application of this directive has been extensively used in relation to workplace violence. Nonetheless, until the day of writing, no specific proposal for a directive dealing with the priority area of bullying has yet been advanced, while various EU bodies have reiterated the need for further action in the area of workplace violence, including regulatory action [42]. However, the opposite opinions argue that the European Council adopted the Safety and Health Framework Directive in 1989, well before public awareness about moral harassment and before the adoption of any legislation. As a result, this directive covers physical rather than psychological safety and health [43].

It is true that Directive 89/391/EEC sets a general framework, for which reason it does not specify any risk in particular, or the risk factors or the measures to be taken within the general prevention policy [44]. But both from its wording and from the interpretation made by the EU Court of Justice case law of 15 November 2001 [45] for example, the Article 6(3)(a) of the directive is understood by the court in its judgement as “to requires employers to evaluate all the risks to the safety and health of workers at work” [46]; and for another example, “it is sufficient to state that the general obligation of the employer to take measures to protect the physical and mental health of workers does not correspond to the specific obligation to evaluate all the risks to the health and safety of workers for the purposes of the directive and in the legal framework established by it” [47]. It may be seen that it applies to all kinds of risks, therefore including psycho-social risks, along with the duty to avoid them, or where this is impossible, to assess them and prevent them [48]. In this sense, according to some scholars, rather than relying on existing legislation, the EU should adopt a new directive to cover moral harassment [49] to make this issue expressly under its jurisdiction. Directorate General of Employment and Social Affairs published an initial draft which announced preparations for Directives on both psychological harassment and violence at work, whereas the final communication states that the Commission will ‘examine the appropriateness and scope of a Community instrument’ on these topics [50].

Framework agreements: In EU, dialogues and negotiations between the representative bodies of employees and employers and other relating workplace parties have resulted in Framework Agreements in relation to moral harassment concerns. From all of these agreements, two in particular stand out since they tackle, on an intersectional basis, occupational health and safety, both of them with reference to psychosocial risks. They are the Framework Agreement on Work-Related Stress (2004) and the subsequent Framework Agreement on Harassment and Violence at Work (2007) [51]. The first, from 2004, was agreed during the timeframe of the fifth Programme on safety and health, the Community strategy on health and safety at work for the period 2001-2006. While describing the phenomena of stress and work-related stress, the agreement provides a framework for employers and workers and their representatives to identify and prevent or manage problems of work-related stress, including moral harassment concerns [52]. The second agreement is to : a) increase the awareness and understanding of employers, workers and their representatives of workplace harassment and violence, provide employers, workers and their representatives at all levels with an action-oriented framework; b) to identify, prevent and manage problems of harassment and violence at work [53]. This agreement reaching strategy has as one of its central aims that of promoting genuine ‘well-being at work’, especially including risks of a moral and social nature, which are precisely the sorts of risks covered by these two agreements. In the framework agreement on harassment and violence at work, the social partners acknowledged that harassment and violence could affect any workplace and any worker [54]. As the directive covers psychosocial issues only indirectly, the framework agreement on work-related stress may be understood as complementing it, though with a weaker legal status (‘soft law’) [55]. In the framework agreement on harassment and violence at work, the social partners acknowledged that harassment and violence could affect any workplace and any worker [56]. The legislative initiatives at all on this subject, but rather these have been finalized in the form of Framework Agreements (on work-related stress and on harassment and violence at work), with a significant weakness in their content and tremendous complexity in their application [57].

In the meantime, it should be noted that the agreements’ efficacy and enforceability is the most interesting at the current time, given that the impact of the Agreements on the legal systems of the Member States is totally different from that of the directives. Due to autonomous nature, application of this kind of agreement in national legal system means that it has to be implemented by the members of the EU signatory parties in accordance with national procedures and practices [58]. This means that the transposition process cannot be considered to be equivalent in the different Member States, and nor will the results be comparable. This has already been reflected in the ‘Report on the implementation of the European social partners’ Framework Agreement on Work-related Stress’ [59]. This report points out that there are ‘persistent discrepancies in the levels of protection’ and concludes that ‘implementation of the Agreement has not yet ensured a minimum degree of effective protection for workers from work-related stress throughout the EU’. Similar problems and deficiencies may be expected in relation to the application of the Framework Agreement on harassment and violence at work [60].

The problem arises from the very nature of the risks and the difficulty in identifying them and establishing the measures necessary in order to prevent them. As a result, the need for effective complementary action by the Member States, or in default of them, by the EU in this matter, may be confirmed. The regulation of specific risks may be one of the aims of the individual directives adopted in accordance with Article 16 of the Directive 89/391, and for this purpose the Commission launched a first round of consultations with the social partners in 2002 on work-related stress, and another one subsequently on harassment and violence at work. However, the adoption of these two Framework Agreements as a solution to these problems is not truly satisfactory, whether from the point of view of the contents [61] or their efficacy and enforceability. However in both cases, it is stated explicitly that they are work-related risks, and this is undoubtedly relevant [62].

Other legal developments: In addition, in the last 5 years, some the significant developments especially at the European level - such as the framework agreements on work-related stress and on harassment and violence at work - have taken place and are currently being implemented and monitored. The newly developed European framework for psychosocial risk management (PRIMA-EF) accommodates all existing major psychosocial risk management approaches across the EU and encapsulates the philosophy of EC health and safety legislation (European Directives) [63]. PRIMA-EF could be used as part of an EU campaign to facilitate convergence and harmonization of perspectives and approaches, and can be used as an awareness tool across stakeholder and other relevant groups [64].

In 2006, the Directive 2006/54/EC on the implementation of the principle of equal opportunities and equal treatment of men and women in matters of employment and occupation [65] was adopted. It contained the very same definitions of harassment related to sex and sexual harassment. Moreover, the Directive bans victimization and encourages Member States to take effective measures to prevent all forms of, interalia, harassment and sexual harassment [66].

Basic concepts

In the academic area, research in the area of hostile behaviors that may be relevant to workplace moral harassment is found in a variety of literatures, using many different concepts such as workplace bullying, emotional abuse, generalized workplace abuse, mistreatment and workplace aggression [67]. In the legal area, moral harassment was known in the laws of several European Union (EU) countries as mobbing (in Sweden, Germany, Italy, and elsewhere), victimization (in Sweden, the first EU country to enact legislation against moral harassment), workplace bullying (the United Kingdom) [68].

At the EU level, the Directive 89/391 requires the employer, "when he entrusts tasks to a worker, to take into consideration the worker's capabilities as regards health and safety. With respect to moral harassment, this provision seems to suggest that the employer should consider the employee's capacity for psychological breakdown when assigning tasks. Given the fact that stresses that moral harassment occurs only when temporary or isolated conflicts escalate in to pervasive harassment, such considerations might have the danger of resulting in unnecessary discrimination before problems in the workforce arise, for example, if a manager were to use a psychological assessment to exclude an employee from a particular work assignment if conflicts are foreseeable.

Social dialogue

In European perspective, moral harassment as part of work-related stress is one of the most commonly reported causes of illness by workers. In combatting this concern, EU has developed an effective mechanism to formulate OHS rules which are agreed by workplace parties. European social dialogue is a relatively novel mode of governance in the area of social policies, in particular in the field of psychosocial risks. At the union level, the EU initiated the EU Project European Framework on Psychosocial Risk Management (PRIMA-EF). This collaborative policy-oriented project focused on the development of a European framework for psychosocial risk management at the work-place, with a special emphasis on work-related stress and workplace violence (including harassment and bullying/mobbing).

Chronically, social dialogue has passed through different stages of development, from a rather passive approach, based mainly on responding to initiatives of the European Commission, to a more proactive and increasingly autonomous approach. According to Ertel et al’s compiling, the first stage (from 1985 up to the early 1990s) involved the adoption of (non-binding) joint opinions through the social partners. The ensuing stage started in 1993, when the social partners obtained the right to be consulted by the Commission on all initiatives and to negotiate and conclude framework agreements which might be adopted as European law. In this phase, the European social partners concluded three binding framework agreements (parental leave, 1995; part-time work, 1997; and fixed-time work, 1999) that were implemented as directives and transposed into national legislation by the member states. In comparison, the social partners broadened, in the third and last stage, their autonomy and concluded three autonomous agreements (telework, 2002; work-related stress, 2004; and harassment and violence at work, 2007).

Although there is emerging perspective that the development of European social dialogue has also been strongly advanced by the employers’ organizations as an alternative to the legislative route and as such it is more effective at the macro level from the industry level above, it is also effective at the level as micro as enterprise as with the information about legal obligations, (financial) consequences and the nature and prevalence of undesirable interaction, they management are encouraged to hold dialogue with the works council, in order decide on how to establish a preventive policy. In this context, it could be said that the European social dialogue may provide some ‘added value to occupational health and safety’ - in particular at the sectoral level - but it would be wrong to believe ‘that one can do without new legislative intervention because (autonomous) social dialogue at several levels could compensate for such intervention’. Therefore, it is necessary to monitor the application of the agreements, and it will probably be advisable to adopt additional measures. It is true that the collective autonomy of the social partners provides full backing for its decisions, but the difficulty inherent to acting in relation to these kinds of risks would have made it advisable to opt for the channel envisaged at Article 155.2 TFEU. This assertion is notably not in accordance with the opinions of the European institutions, which consider social dialogue ‘to be an essential instrument of governance given the proximity of the social partners to the requirements of the reality of working environments’.

Implementation in member states

Sweden was the first EU country to enact legislation against moral harassment. Luxembourg signed its first collective agreement on moral harassment in 2001, a Spanish court held in 2001 that workers were entitled to receive compensation for an "industrial accident" caused by moral harassment, and Belgium enacted legislation against moral harassment in 2002. In UK, the Prevention of Harassment Act 1997 makes it unlawful to harass another person for any reason. And it is not necessary to demonstrate a discriminatory reason under this legislation. The decision of Majrowski v. Guy’s and St. Thomas’s NHS Trust demonstrated that harassment under the Act is both a criminal offence and it can give rise to a claim in civil proceedings and that Employers may be vicariously liable for harassment committed by their employees, provided that it took place in the course of their employment. In addition, Equality Act 2010 prohibits discrimination based on the personal characteristics of age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex, and sexual orientation. This applies to the workplace and it includes an express prohibition of harassment. Regarding another important member state France, which has been deeply influenced by the EU’s approach in expanding occupational health from the physical aspect to including its mental meaning has rooted in its important member states’ legal reform. The concept of health at work has significantly changed in the course of time. Originally only the occupational accidents (in their physical aspects) were protected by the French law. Since 1919, professional diseases have been progressively taken into account, and in 2002 health, which was first considered only in its physical aspect, have been regarded also in its mental meaning. So, presently, the physical and mental health is protected in French Labour and Social Security Law. One of the most common different kinds of psychical risk is moral harassment in the French law, which has adopted a specific legislation about the issues. To better help readers to conceptualize the laws adopted in member states in implementing the EU law, here below is a table list the major member states’ legislations in this respect.

Comparisons of the Chinese and EU Systems

Based on the above analyses of the legal norms, here below, it is continued to compare the two systems:

Physical vs. physical and psychological

Until the day of writing, in the Chinese system, a special law focused on preventing the prevention of moral harassment is not adopted neither is put on the legislature’s law-making agenda. Moreover, the psychological health as a whole is hardly mentioned in this system, causing difficulties in preventing moral harassment at the workplace. In contrast, EU law has long recognized psychological risks as occupational hazards in occupational health and safety legislation. This recognition has had a major impact on the EU law. Even though, the same as Chinese system, EU has until now not adopted special legislation vis-à-vis moral harassment, despite, as earlier stated, both legal scholars and politicians call for doing so, including psychological risks in the occupational hazards can effectively provide legal basis to some extent for preventing moral harassment. In the meantime, the European legislators have taken use of policy approaches - to define moral harassment as a violation of dignity, as well as to combine sexual and gender harassment with “mobbing,” and bullying of all workers. These approaches above can all prompt Chinese legislators to reexamine their approaches.

Sexual harassment vs. general moral harassment

It seems in the Chinese system, the definition of moral harassment is narrow as limited to including no much more than sexual harassment. This could be understood due to the fact that Chinese society has only recently begun to undergo sexual revolution and along with public concern about the new modalities of sexual behavior, media reports suggest that the perceived growth of sexual harassment has also risen in salience as a societal focus, leading to serious counter-harassment efforts by the government. As a result, the current system (for example, civil law, Women's Protection Law) has spent significant length in regulating how sexual harassment should be prevented and violations should be sanctioned in the context of prohibiting the civil infringement of reputation and personal dignity. However, the regulating moral harassment excluding sexual harassment is hardly toughed. This leads to the danger of leaving the rest in the moral harassment largely unregulated. In contrast, in European laws, although the Directive 89/391, framework directive in the field of occupational health and safety, does not expressly stipulate the wording “moral harassment”, it is clear that moral harassment is covered under the Safety and Health Framework Directive, through the current position of the European Commission. Moreover, moral harassment is stipulated as comprehensive concept, including extensively, and as provides basis for entitling workers to receive compensation for an "industrial accident" caused by moral harassment.

Legislations vs. legislations combined with agreements

In addition to lacking a specific legislation combatting the moral harassment, the current potential legal basis to prevent this concern at Chinese workplaces is found primarily in statutory laws, as illustrated in Table 1 the Legislative Hierarchy in the field of Preventing Moral Harassment at Work in the first section. However, moral harassment is in nature a workplace violence, and consequently, the workplace parties should be more acknowledged about the detailed rules in distinguishing what behaviours should be recognized as moral harassment, as well the rules that can effectively prevent moral harassment. The shortcoming of the Chinese approach at this point is that rule-making power is completely in the hands of the legislators who are sitting in office, while the statutory rules, made by legislator cannot be adequate in covering moral harassment concerns. In contrast, in the European system, the agreement mechanisms are introduced to formulating framework agreements to cover the detailed rules in the context of guidelines provided by statutory laws. In the meantime, as stated before, the EU Directive 89/391 covers psychosocial issues only indirectly, the framework agreement on work-related stress may also be understood as complementing it, though with a weaker legal status (‘soft law’).

| Country | Legislation |

| United Kingdom | The Equality Act 2010; The Prevention of Harassment Act 1997 |

| Italy | Decree-Law No 242 1996; |

| France | Social Modernization Law, and Labor and Penal Codes |

| Sweden | Ordinance on Victimization at Work 1993; The Working Environment Act |

| Germany | General Equal Treatment Act of 2006; the Occupational Health and Safety Act of 1996 (Arbeitsschutzgesetz) |

| Austria | "Antistalking Act", 2006 Act Amending Criminal Law |

| Portugal | Law No. 98/2009; Decree Law No. 142/99 |

| Denmark | Law number 1385, 2005; |

| Poland | the Labour Code and the 2010 Antidiscrimination Law |

| Belgium | The Law on Violence, Moral Harassment and Sexual Harassment at work 2002 |

| The Netherlands | The Working Environment Act |

Table 1: Member states’ legislations.

Conclusion

The moral harassment at workplace is hardly a new phenomenon. Mistreatment of workers in the workplace has always existed. However, as we know, psychological harassment in the workplace did not appear with the recognition in China until in 2005 when the regulations against sexual harassment were added into the women’s protection legislation. After the development in the last decade, China has adopted a legal system against this concern based on not specific moral harassment but instead provisions of relating laws. In the EU, the regulatory history is much longer. The system is built primarily based on the OHS Framework Directive 89/391. In the meantime, it is supplemented by framework agreements. Through the comparisons of legal norms, it is found that China can learn from the EU by including psychological risks in the occupational hazards, stipulating moral harassment as more comprehensive concept include its complete content in the legal text, and to Adopting ‘soft laws’ in order to complement the statutory laws.

References

- Maria Isabel Guerrero S (2004). The Development of Moral Harassment (Or Mobbing) Law In Sweden and France as a Step towards EU Legislation. Boston College International & Comparative Law Review. 27:477

- Costa ACR (2014) Moral Harassment under Portuguese Law: One Step Behind? E-Journal of International and Comparative LABOUR STUDIES 3: 2.

- Corinne Sachs-Durand (2013) Occupational Health and Safety in France: A Good Formal Protection, but a Problematic Efficiency, in: Edoardo Ales (ed.) Health and Safety at Work: European and Comparative Perspective. Kluwer Law International, p123

- Corinne Sachs-Durand (2013) Occupational Health and Safety in France: A Good Formal Protection, but a Problematic Efficiency, in: Edoardo Ales (ed.) Health and Safety at Work: European and Comparative Perspective. Kluwer Law International p103.

- European Parliament Resolution on Harassment at the Workplace, 2001/2339(1NI) .

- Schaufeli WB,Kompier MAJ (2002) Managing Job Stress in the Netherlands.TUTB Newsletter 19-20: 31-38

- Ertel M, Stilijanow U, Iavicoli S, Natali E, Jain A, et al. (2010) European social dialogue on psychosocial risks at work: Benefits and challenges. European Journal of Industrial Relations 16: 169-183.

- LerougeL (2010-2011) Moral Harassment in the Workplace: French Law and European Perspectives. Comparative Labor Law & Policy Journal.

- Jiyuan Z, WenyuW, Ying Z (2012) An investigation and analysis on negative behaviors in the workplace in China.

- Jiang J, Jiao D, RongW (2012) Workplace bullying´╝?employees depression and job satisfaction: Moderating effect of coping strategies.Chinese Mental Health Journal 26.

- Minghui Liu (2011) Special legislation on the new concept of protection of women workers. Academic Journal of China Women's University

- See Article 38 of the Constitution.

- Xinbao Z and Yanzhu G (2006) The Main Issues In The Legal Regulation Concerning Preventing Moral Harassment. The Journal of Jurist.

- Wenjing Qi (2008) Comparative Analysis of the Legal Concept of Sexual Harassment. The Journal of Comparative Legal Research.

- See Article 101 and Article 120 of General Principles of the Civil Law.

- See Article 40 of the Law on the Protection of Women’s Rights and Interests.

- See Article 58 of the Law on the Protection of Women’s Rights and Interests.

- Schneider KT and Swan S (1997) Job-Related and Psychological Effects of Sexual Harassment in the Workplace: Empirical Evidence from Two Organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology

- Li Y, Nie G, Li Y, Wang M and Zhao G (2011) Research on the Content and Scope of Moral Harassment At Workplace. Psychology Science.

- Anne Renaut (2003) Moral Harassment: Work Organization to Blame? International Labour Organization pp1-3.

- See Article 13 of the Occupational Disease Prevention Law.

- Glomb TM, Richman WL, Hulin CL, Drasgow F, Kimberly T (1997) Ambient Sexual Harassment: An Integrated Model of Antecedents and Consequences. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes; 71:309-328.

- See Article 15 of the Labour Law. Article 15 of the Labor Law prohibits an employer to recruit minors under the age of sixteen, with exception made for institutions of literature, art, physical culture, and special crafts which may recruit minors through investigation and approval of the government authorities, and must guarantee the minors’ rights to compulsory education.

- Article 2 Minors as used in this Law refer to citizens under the age of eighteen. See Article 2 of the Minors Protection Law.

- Article 28 of the Minors Protection Law.

- Article 15 of Mental Health Law.

- See Article 2 of the Trade Union Law.

- Martin Krzywdzinski. Between Europe and Asia: Labour Relations in German Companies in Russia and China. In: Richet X, DelteilV, DieuaideP (eds) Strategies of Multinational Corporations and Social Regulations: European and Asian Perspectives. Springer Publishing, p. 143.

- Zhu Y, Fahey S (2010) The challenges and opportunities for the trade union movement in the transition era: Two socialist market economies-China and Vietnam. Asia Pacific Business Review.

- Anita Chan (Fall - Winter, 2002) Labor in Waiting: The International Trade Union Movement and China. New Labor Forum 11: pp. 54-59

- See Article 4 of the Occupational Disease Prevention Law.

- Tang C (2001) Research on Moral Harassment in Workplace Controlling and Preventing. Women Studies.

- Lin J, Deng J (2009) The Normative Change in Chinese Labour Law. The Journal of Politics and Law.

- Chen Y (2004) Research on the Legal Issues in Moral Harassment. Journal of Xiamen University Law Review.

- Clarke S, Pringle T (2007) Labour activism and the reform of trade unions in Russia, China and Vietnam. NGPA Labour Workshop

- Article 58 of the Women’s Right Protection Law.

- Article 10 of the Public Security Administration Punishments Law.

- COM (2007) 62 final, 14.

- See article 31 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.

- See Article 118a.1 of the EC Treaty.

- See judgment of the Court of Justice, Case C-84/94.

- Martino VD, Hoel H, Cooper CL (2003) Preventing violence and harassment in the workplace. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions.

- Berta Valdés de la Vega (2013) Chapter 1: Occupational Health and Safety: An EU Law Perspective, in: Edoardo Ales(ed.) Health and Safety at Work: European and Comparative Perspective. Kluwer Law International pp20-21.

- Case C-49/00, Commission of the European Communities v. Italian Republic.

- See: JUDGMENT OF 15. 11. 2001 — CASE C-49/00.

- See L. Vogel, ‘Long on ideas, short on means’, TUTB Newsletter, March 2002, No. 18, p. 3.

- Within this same categoryof ‘Autonomous Agreements’executedby social partners, we find the Framework Agreement on inclusive labour markets(2010), and the Framework Agreement on telework(2002).

- Implementation of the European Autonomous Framework Agreement On Work-Related Stress. Report by the European Social Partners Adopted at the Social Dialogue Committee(2008).

- See Framework Agreement On Harassment And Violence At Work (2007).

- Ertel M, Stilijanow U, Iavicoli S, Natali E, Jain A, LekaS (2010) European social dialogue on psychosocial risks at work: Benefits and challenges. European Journal of Industrial Relations 16.

- de la Vega BV (2013) Chapter 1: Occupational Health and Safety: An EU Law Perspective.In: Ales E (ed) Health and Safety at Work: European and Comparative Perspective. Kluwer Law International p15.

- Falkner G (2000) The Council or the social partners? EC social policy between diplomacy and collective bargaining. Journal of European Public Policy 7

- Commission StaffWorkingPaper‘Reportontheimplementation oftheEuropeansocial partners’ Framework Agreementon Work-related Stress’ SEC (2011) 241 final.

- Ales E (2013) Chapter 12 Occupational Health and Safety: A Comparative Perspective.In: Ales E (ed) Health and Safety at Work: European and Comparative Perspective. Kluwer Law International.

- For example,the aim of the Framework Agreementon work-related stressis not directlythe improvement of health,but rather‘increasingawareness and understanding’ of this problem. As such, the agreement does not provide any definitionof stress, but only describesit in a way thatis ‘intentionally vague,scientificallyinaccurate, besidesbeing individually focussedand subjective’, accordingto M. Peruzzi,‘The prevention of psychosocial risks in European Union law’, I WorkingPapers di Olympus,no. 14 (2012): www.uniurb.it/olympus,27.

- MuñozRuizAB (2009)TheregulatorySystem of prevention of OccupationalRisks (Valladolid:Lex Nova 121

- Leka S, Jain A, Iavicoli S, Vartia M,ErtelM (2011)The role of policy for the management of psychosocial risks at the workplace in the European Union. Safety Science 49:558-564

- Harassment related to Sex and Sexual Harassment Law in 33 European Countries: Discrimination versus Dignity. European Network Of Legal Experts In The Field Of Gender Equality (2011) P1.

- Einarsen S, Hoel H, Zapf D, Cooper C (2003) Bullying and Emotional Abuse in the Workplace: International Perspectives in Research and Practice. Taylor & Francis preface

- Issue 2 Interrelationships: International Economic Law and Developing Countries.

- See Article 6 of the Directive 89/391/EEC.

- European Foundation (2007) Fourth European Working Conditions Survey, 2005. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Vogel, supra note 1, at 23; Pep Espluga, Court Rulings Recognise Bullying as "Occupational Risk,"EIRONLINE (2002)

- Marc Feyereisen, First Collective Agreement Signed on Moral/PsychologicalHarassment, EIRONLINE (2001)

- Bell M (2013) Occupational Health and Safety in the UK: At a Crossroads?In: Ales E (ed) Health and Safety at Work: European and Comparative Perspective. Kluwer Law International p. 383.

- Majrowski V (2006) Guy’s and St. Thomas’s NHS Trust IRLR 695 (HL)

- Corinne Sachs-Durand (2013) CHAPTER 4: Occupational Health and Safety in France: A Good Formal Protection, but a Problematic Efficiency.In: Ales E (ed) Health and Safety at Work: European and Comparative Perspective. Kluwer Law International pp. 100-101.

- William Parish L, Aniruddha Das and Edward Laumann O(2006) Sexual Harassment of Women in Urban China. Archives of Sexual Behavior 35:411-425.

Relevant Topics

- Child Health Education

- Construction Safety

- Dental Health Education

- Holistic Health Education

- Industrial Hygiene

- Nursing Health Education

- Occupational and Environmental Medicine

- Occupational Dermatitis

- Occupational Disorders

- Occupational Exposures

- Occupational Medicine

- Occupational Physical Therapy

- Occupational Rehabilitation

- Occupational Standards

- Occupational Therapist Practice

- Occupational Therapy

- Occupational Therapy Devices & Market Analysis

- Occupational Toxicology

- Oral Health Education

- Paediatric Occupational Therapy

- Perinatal Mental Health

- Pleural Mesothelioma

- Recreation Therapy

- Sensory Integration Therapy

- Workplace Safety & Stress

- Workplace Safety Culture

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 30011

- [From(publication date):

August-2015 - Nov 21, 2024] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 25363

- PDF downloads : 4648