Common Bean Improvement Status (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in Ethiopia

Received: 28-Feb-2018 / Accepted Date: 20-Mar-2018 / Published Date: 26-Mar-2018 DOI: 10.4172/2329-8863.1000347

Abstract

Common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L; 2n=22) is the most important food legume rich in protein, minerals, and vitamins where its protein content is cheap and easily affordable for the famers of the country. The crop plays great role in maintaining the fertility of the soil through fixing atmospheric nitrogen and thus keeping diversity and stability of the agricultural system. Due to its importance, the total area allocated for common bean crop production and the yield obtained in Ethiopia is 357,299.89 ha and 540,238.94 tons respectively. The productivity of white and red common bean is 1.41 ton/ha and 1.59 ton/ha respectively in 2016 planting season. Since 1970s common bean improvement has been started in Ethiopia and since then more than 50 common bean varieties for different traits and for different agro ecologies were released through conventional breeding in Ethiopia. Currently, in common bean breeding; gene pyramiding against common bean diseases like ALS (Angular Leaf Spot), CBB (Common Bean Blight) and anthracnose and diversity assessment for diseases like CBB and ALS has been started using MAS (Marker Assisted Selection) in Southern Agricultural Research Institute at Hawassa. Therefore the aim of this article is to review common bean improvement status and to indicate some improvement gaps in Ethiopia.

Keywords: Protein, Fertility, Stability, Production, Productivity, Conventional breeding, Gene pyramiding

Introduction

Common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L; 2n=22) is the world’s most important food legume which is used for direct human consumption. he common bean production is greater than 12 million tons annually in the world with its production value of US million $5717 [1,2]. Since it is high in nutrient content and commercial potential, common bean holds great promise for fighting hunger, increasing income and improving soil fertility in Sub Saharan Africa. he crop occupies more than 3.5 million hectares in sub-Saharan, but production is concentrated in the densely populated areas of East Africa, the lakes region and the highlands of southern Africa. It is the second most important crop next to cow pea in eastern, central, and southern Africa [3,4]. hese regions are the primary bean growing regions in Africa, with a combined production of almost 1 million metric tons [5].

It is one of the major food and cash crops in Ethiopia and it has considerable national economic significance and also traditionally ensures food security in Ethiopia [6-8]. It ranks third as an export commodity in Ethiopia, contributing about 9.5% of total export value from agriculture. It is often grown as cash crop by small scale farmers. The majority of common bean producers in Ethiopia are small scale farmers, and it is used as a major food legume in many parts of the country where it is consumed in different types of traditional dishes [9].

Common bean seeds contain 20-25% proteins, much of which is made up of the storage Protein phaseolin [10]. Phaseolin is a major determinant of both quantity and nutritional quality of proteins in bean seeds [11,12]. In addition to this; it is also important in providing fodder for feeding livestock and it contributes to soil fertility improvement through atmospheric nitrogen fixation during the cropping season [5,13]. Common bean adds not only diversity to production systems on resource poor farmers’ fields but also it contributes to the stability of farming systems in Ethiopia [13].

Pulses covered 10.38% (about 2,671,843.040 tons) of the grain production. Out of this, common beans (red), and common beans (white) were planted to, 1.95% (about 244,049.94 ha) and 0.91% (about 113,249.95 ha) of the grain crop area respectively. The production obtained from common bean (red) and common bean (white) were 1.43% (380,499.453 tons) and 0.60% (159,739.484 tons) of the grain production respectively. Therefore, the total area devoted for common bean crop production and the yield obtained in Ethiopia are 357,299.89 ha and 540,238.94 tons respectively [14]. Common bean is mainly grown in Eastern, Southern, South Western and the Rift valley areas of Ethiopia [15]. Even though the crop has tremendous importance in country economy such as for home consumption, soil fertility improvement and etc., its improvement is highly challenged by diseases, insect pests, and prolonged drought in Ethiopia. In spite of this challenge, the crop is crucial primarily for home consumption, for foreign exchange earnings, soil fertility improvement by changing unavailable atmospheric nitrogen into available form and it has high protein content. This urges us to know about the improvement status of common bean so that to suggest the gaps of the improvement process as a result appropriate intervention to be taken by the concerned bodies.

Objective: The objective of this paper is to review the improvement status of common bean in Ethiopia and to point out improvement gaps on the crop so as appropriate intervention to be taken.

Botany of common bean

Common bean usually refers to food legumes which belong to genus Phaseolus , species vulgaris , family Leguminosae , subfamily Papilionoideae , tribe Phaseoleae , sub tribe Phaseolinae . The genus Phaseolus contains some 50 wild-growing species distributed only in the Americas. The Asian Phaseolus have been re- classified as Vigna [16]. According to Kaplan [17] like many other plants, common beans are hermaphroditic, containing both the stamen and pistil in the same flower. This makes common bean self-fertile, which means an individual plant is able to reproduce by itself which can have the effect of limiting genetic diversity. Common bean represents a wide range of life histories (annual to perennial), growth habits (bush to climbing), reproductive systems and adaptations (from cool to warm and dry to wet). The seeds of common bean are non-endospermic (for fabaceae the endosperm is not retained as storage tissue; it is used up to put storage chemical into the embryo itself) and they differ in seed size and color. The Andean lines have larger seeds in which 100 seed weight is above 30 grams while Mesoamerican lines have smaller seed size i.e., their 100 seed weight is less than 30 grams [18]. The seed size of common bean can be i/small when randomly measured 100 seed weight is below 25 grams, ii/ medium when 100 seed weight is between 25 and 40 grams and iii/ large when 100 seed weight is above 40 grams. Besides, the seed color of the crop varies from the small black wild type to the large white, brown, red, black or mottled seeds [19]. Common bean shows variation in growth habits that could be bushy determinate, bushy indeterminate, prostrate indeterminate and extreme climbing indeterminate types [20].

Origin and geographic distribution of common bean

Common bean is believed to have two centres of origin. These are South America, Andean region (mainly Peru) and Middle America (Southern Mexico and High lands of Guatemala). The basis of the origin is based on DNA analysis that shows the simplest DNA structures exist in wild beans from these regions of Ecuador and Peru. Those common bean accessions domesticated in the Andean regions from Ecuador south are considered as the Andean gene pool, whereas those domesticated from Colombia northwards belong to the Middle American gene pool [21]. However, according to Jones [22] the centre of origin of common bean is considered to be the central Andes, Central America, and Mexico. Other archaeological evidence showed that common bean was domesticated 5000 BC in Peru and in 6000 BC in Southern Mexico [23]. Then, from its centre of origin common bean is introduced into Brazil and East Africa in the 17th century by the Portuguese. Similarly, it is believed to be introduced into Ethiopia in the same century by the Portuguese.

Adaptation and agro-ecology of common bean

Common bean is adapted to a wide range of climatic conditions ranging from sea level to nearly 3000 meters above sea level (m.a.s.l.) depending on variety. However, it does not grow well below 600 meters due to poor pod set caused by high temperature [24]. It grows best in warm climate at temperature range of 18°C to 24°C [25]. Fikru [26] suggested that common bean grows well between 1400 and 2000 m.a.s.l. In addition, Kay [27] reported that the crop is well adapted to areas that receive an annual average rainfall ranging from 500-1500 mm with optimum temperature range of 16°C-24°C, and a frost-free period of 105 to 120 days for maturity. Moreover, common bean performs best on deep, friable and well aerated soil types with optimum pH range of 6.0 to 6.8. The major common bean producing areas of Ethiopia are central, eastern and southern parts of the country [14].

Production and economic importance of common bean in Ethiopia

According to CSA [14], the area covered by common bean production in Ethiopia in 2016 was 113,249.95 ha and 244,049.94 ha for white and red common bean respectively with total area of 357,299.89 ha and total production of about 540,238.94 tons/ha. Generally, pulses covered 13.24% of the grain crop area; where common bean, faba bean and chickpea accounted for 2.86%, 3.56% and 2.07% respectively. Thus, common bean ranks second next to faba bean in terms of area coverage among pulse crops. The average white and red common bean productivity is 1.41 tons/ha and 1.56 tons/ha respectively. It is predominantly produced in Oromia region, SNNPR and Amhara region with their area coverage of 146,452.41 ha (41%), 117,969.97 ha (33%) and 81,235.07 (22.74%) ha respectively. The rest 3.25% is produced in other regions of Ethiopia [14]. Rahameto [28] reported that in the southern part of the country, Sidama and Gamo Gofa zones produce red and speckled types mainly for home consumption. In the eastern part; mainly Hararghe highlands, where low land pulses are being preferred for food and they are mostly speckled food beans and small whites.

Common bean is mostly grown in small and medium sized farms due to small land holding of most of the farmers in Ethiopia. Taking into account its nutritional value, the crop is rich in protein, carbohydrates, minerals and vitamins. The protein content in beans can reach up to 40%, whereas the protein content of meat is approximately 20% which cannot easily be afforded by the poor farmers. Common bean fits very well into crop rotation where it can successfully be intercropped with crops like maize or cassava and has demand in both domestic and regional markets in Africa [29].

When common bean economic importance is considered, it is used as source of foreign currency, food crop, means of employment, source of cash, and plays great role in diversifying the farming system [14]. EPPA [30] reported that in the year 2000, 2001 and 2002 Ethiopia exported 23,994.4, 32,932.7 and 42,127 tons of common bean obtaining 8.2, 9.8 and 13.2 million USD respectively. The main destination markets in 2002 were Pakistan, Germany, Yemen, UK, South Africa, India and Mexico having 12.9, 7.8, 6.9, 5.79, 4,4,4% respectively [30]. The country's export of common beans have increased over the last few years, from 58,126 MTs in the year 2005 to 78,271 MTs in the year 2007 and Ethiopia obtained 63 million dollar from common bean market in 2005 [31]. The major storage and trading sites in Ethiopia is in the southern rift valley areas like in the towns of Wolaita sodo, Hawassa and Shashemene whereas the major collection centres for white beans is in Nazareth, before it is exported through Djibouti [32,33]. For the major processing companies, Ethiopia is a relatively new source of supply and recent investment site for a number of international companies like Italy, UK and Turkey. These countries are importing from Ethiopia and this indicates that market opportunities are boosting in the country even though the demand of the consumers in the country is not yet being fulfilled [34].

Historical Development And Success Of Common Bean Improvement In Ethiopia

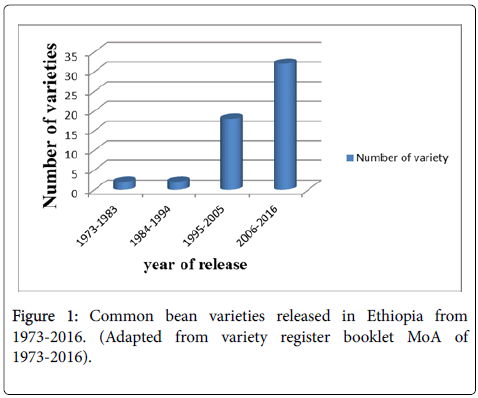

Common bean research in Ethiopia began in the late 1960s. However, a nationally coordinated research in Ethiopia began in the early 1970s by the Melkassa Agricultural Research Center (MARC). So far, a large number of common bean germplasm were introduced and evaluated for adaptation and productivity. In the early 1980s, priority was set [35]. Since then more than 50 common bean varieties have been released for some specific traits and for different altitude ranges (Figure 1). The national strategy to develop improved bean varieties has evolved over time. In the past, evaluation of promising improved bean lines was done across several growing environments, with the expectation of identifying varieties adapted to a range of different growing conditions [36]. The country’s universities have been playing their role in the improvement program of common bean in Ethiopia. The Hawassa University common bean improvement program is the coordination centre in the eastern and central Africa regional program and played its role in establishing its common bean crossing program for sources of germplasm to the eastern and central Africa regions bean network (ECABRN) countries. The Haramaya University is also playing a significant role in the improvement of common bean in Ethiopia. In addition to MARC and the Universities, other EIAR (Ethiopia Institute of Agricultural Research) centres and SARI (Southern Agricultural Research Institute) centres has been playing their role in the improvement of common bean in Ethiopia. However, only few genotypes would be suitable to all beans growing environments because of differences in consumer preferences and specificity in adaptation to climatic conditions and cropping systems. Subsequently, several varieties have been released to address the issues related to climatic adaptation and different consumer preferences.

All the bean breeding activities in Ethiopia have been conventional until recently. However, since 2015, an attempt is being made at SARI where molecular laboratory is established and functioning, although it is at infant stage. Even though it is in the infant stage, some of the MAS (Marker Assisted Selection) activities have been started. The gene pyramiding against common bean diseases like ALS (Angular Leaf Spot), CBB(Common Bean Blight) and anthracnose is at BC4 (back cross four) stage by crossing the recurrent parent with the donor parent for the three diseases. In addition to gene pyramiding, diversity assessment for diseases like CBB and ALS is also underway.

Between 1973 and 2016, even though there is no significant common bean improvement status difference in two decades, the improvement of common bean varieties was rapidly increased (Figure 1) after 1995 and brought significant change in the food security and farmers’ income. Women are the main beneficiaries. Due to improvement, its yield has been increased by 50% in Ethiopia over the last decade [36]. As it is indicated in Table 1, through introduction of germplasm of different market classes and testing across different agro ecologies in which different diseases are prevailing more than 18 multiple disease resistance varieties of common bean has been released by the NARS (National Agricultural Research System).

| Official Name | Local Name | Release year | Yield (tons/ha) | Resistant/ Tolerant to | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| On research station | On Farmers’ land | ||||

| SER-125 | SER-125 | 2014 | 3.2 | 2.5 | ALB, Rust |

| Awash-2 | Awash-2 | 2013 | 2.8-3.1 | 1.8-2.2 | Rust |

| KATB69 | Dandesu | 2013 | 2.2-3.0 | 1.9-2.3 | CBB |

| KATB1 | Ada | 2013 | 1.9-3.3 | 1.7-2.5 | CBB |

| AFR-716 | Loko | 2009 | 2.1 | 1.8 | ALS, Anthracnose |

| SNNPR-120 | Hawassa Dume | 2008 | 2.5 | 2 | ALS, CBB, HB |

| SUG131 | Deme | 2008 | 1.9-2.0 | 1.8-2.2 | Anth, ALS, CBB |

| Vax-2 | Gabisa | 2007 | 2.4 | 2.5 | CBB |

| STTT-165-96 | Chercher | 2006 | 2.2-3.0 | 1.5-2.5 | CBB, ALS |

| G-843 | Haramaya | 2006 | 2.5-3.5 | 1.8-2.2 | CBB, Rust |

| STTT-165-92 | Chore | 2006 | 2.3-2.5 | 1.9-2.2 | Anth, CBB, Rust |

| Rab-484 | Melkadima | 2006 | 2.0-3.2 | 1.8-2 | Anth, CBB, Rust |

| Xan-310 | Dinknesh | 2006 | 2.5-3.2 | 2-2.5 | Anthracnose, rust |

| EMP-376 | Anger | 2005 | 2.3 | 1.7 | ALS |

| - | Tibe | 2004 | 2.2 | 1.8 | Anth, CBB, Rust |

| Dicta-105 | Nasir | 2003 | 3.0 | 2.3-2.7 | Anth, CBB, Rust |

| ISC-15541 | Gobe Rasha-1 | 1999 | 2.1 | 1.8 | ALS |

| Pan -182 | Awash Melka | 1999 | 3 | 2.7 | Anth, CBB, Rust |

| GLPX 92 | Ayenew | 1997 | 2.0-3.5 | 1.5-2.8 | CBB, Rust |

| G-2816 | Gofta | 1997 | 2.4-4.0 | 1.5-3.0 | CBB, Rust |

| Roba-1 | Roba-1 | 1997 | 2 | 1.6 | Anth, CBB, Rust |

Table 1: Research attempts and some of the achievements in common bean improvement. (Adapted from variety register booklet MoA of 1997-2014).

Commonly used breeding techniques for common bean improvement

The Ethiopian national common bean improvement program has been trying to release promising bean varieties through crop improvement techniques [34]. Crop improvement is achieved through introduction, using different selection methods and hybridizing plants with desired traits. Introduction is the earliest plant breeding method and it is taking of the superior plant varieties with desired trait from one area to the newer area for immediate use after evaluating in certain area with in shorter period of time. This method is not currently applied in Ethiopia. Selection is the preferential survival and reproduction or preferential elimination of individuals with certain genetic compositions by means of natural or artificial controlling factors. It is the most commonly used breeding technique in Ethiopia probably due to the use of already existing natural variation to select the best performing genotype, no need of cost for creating artificial variation. The majority of common bean varieties released in Ethiopia are developed by using selection breeding methods like mass selection; pure line selection, bulk selection and backcross method. In addition to selection, sometimes hybridization is used to cross two genotypes with dissimilar but with desirable traits to produce hybrid. Recently gene pyramiding common bean against diseases like ALS, CBB and anthracnose is undertaken at SARI. In addition, assessing diversity of common bean diseases like CBB and ALS is also underway. Gene pyramiding is arranging multiple genes leading to simultaneous expression more than one gene in a cultivar to produce long lasting resistance expression of genes in which success depends on the number of genes to be transferred and the distance between the target gene and the flanking markers, the number of genotypes selected in each breeding generation the nature of germplasm [37] etc.

Challenges and opportunities of common bean improvement in Ethiopia

Opportunities: Common bean improvement; in Ethiopia, has its own opportunities to achieve such impressive result. The common bean improvement program of the country is supported by budget by International projects, national projects and government of the country. Currently, it is supported by CIAT (International Centre for Tropical Agriculture), PABRA (Pan Africa Bean Research Alliance), TL (Tropical Legume) and others [36]. The Ethiopian government has given due emphasis to the improvement of common bean due to its export value [30]. This support alleviates the budget challenges that would have been occurred in the improvement program. The existence of diversity between the Mesoamerica gene pool and Andean gene pool type of common bean helps for variety selection of different traits; like high yielding, disease resistance or tolerance and drought tolerance. In spite of the high level of brain erosion from the country, some of the country lovers work hard to bring this visible change in the improvement of common bean. The establishment of research centres based on agro ecology of the country is also an excellent opportunity to advance the improvement of common bean in multi locations; i.e., to exploit the genotype by environment response of selection so that to recommend varieties according to their performance.

Challenges: Even though more than 50 common bean varieties are released by the NARS, due to less cooperation between agricultural extension and development offices and NARS of the country, few varieties (Red wolaita, Hawassa dume, Nasser etc.) dominate the production system; particularly, in the SNNPR regions of Ethiopia. It is clear that, in the crop improvement the target is making the farmers beneficial from the high yielding improved common bean varieties. Unless the improved common bean varieties reach to the producers, this may discourage the breeding system and make all the effort of the breeders futile.

According to the suggestion of Tumsa et al. [38] the other challenge could be the dependency of breeding system only in conventional breeding and lack of basic molecular level research techniques and skill. The limitation of conventional breeding is that the time it takes to achieve desired result, it does not ensure the transfer of target gene, it is limited to only closely related species and also un-desirable gene may transfer along with desirable gene. These make the conventional breeding system less efficient in answering the question of the end users. These authors added the shortage of facilities such as screening houses; green houses and laboratory facilities weaken the breeding system. The source of resistance for some disease is also not known.

According to Anderson et al. [39] bio fortification is the process of breeding nutrients into food crops; it is feasible means of delivering micronutrients to populations that may have limited access to diverse diets, supplements, or commercially fortified foods. Breeding for bio fortified food crops is another challenge probably due to lack of expertise and molecular laboratories in Ethiopia. The other is the genetic base of most common bean cultivars with in marker class is narrow [40] because only a small portion wild common bean population was imported. The narrow genetic base of cultivars is attributed to the limited use of exotic germplasm [41].

In addition, the improvement of common bean is influenced by both abiotic and biotic factors. The abiotic factors include climatic and soil factors; whereas biotic factors are diseases and insect pests. Beans are subjected to both field and storage insect pest attack. The Bean Stem Maggot (BSM) and bruchids significantly affects production and productivity. In Africa, due to BSM yield losses ranging from 30-100% have been reported. In Ethiopia, Z. subfasciatus and C. maculatus are the major pests of stored beans causing average grain losses of 60% within 3-6 months of storage period. Much of the bean crop is lost due to diseases as well as insect pests or drought, low soil-fertility and other abiotic stresses [42]. Bean rust (Uromyces appendiculatus ) disease accounts for a yield losses of 85%, and Angular leaf spot (Phaeoisariopsis griseola ) disease yield reductions is not quantified in Ethiopia but elsewhere range from 7 to 80%. The Anthracnose (Colletotrichum lindemuthianum ) is another disease of common bean that causes yield reduction [38].

Future Research Prospects Of Common Bean

The National Agricultural Research System has been doing great effort varieties to be improved on the base of the set standards. However, population is increasing at alarming rate. According to rapid situational analysis field report of 2007, the population of Ethiopia increases by 2.6% every year. Thus, to feed this increasing population; the quick and less expensive way of variety improvement is expected to be followed which saves resource like time and cost. As it is indicated earlier, the common bean improvement system in our country is more of conventional breeding method which may take 8-12 years for selection of improved variety from accessions. To feed this increasing population of the country, breeding should focus on molecular breeding methods where varieties can be improved relatively with in shorter period of time with desired trait. In addition to this, introducing superior released materials and evaluating them over locations and then finally releasing to the farmers is preferable method to answer the food question of this increasing population.

Since the crop is not indigenous to our country, so germplasm has be introduced from the centre of origin and diversity and thus evaluated in different agro ecologies. In Ethiopia, the traits are supposed to be identified on morphological characterization, therefore; molecular base identification studies are expected to done in the future for desired trait identification. The creation of magic population; population which may contain many traits at a time, needs to be part of our research focus area for a future. Because this may solve many research questions of common bean at a time.

Summary and Conclusion

Common bean improvement is in the promising status in Ethiopia even though it has got research attention since 1970s. This is probably due to the nutritive value and soil fertility maintenance nature of the crop. In addition to this, its use for export to earn foreign currency may be another reason for the preference of the crop. Since then, the crop is majorly produced in Eastern, Southern, South Western and Rift valley areas of the country. Since 1970’s, more than 50 common bean varieties have been released for different ecologies of specific common bean traits. In these five decades, though the improvement status of common bean is not constant; the number of varieties released in every ten years has been increasing linearly.

For the future, the common bean improvement is expected to be enhanced with the support of molecular breeding method by which specific trait to be inserted is done relatively easily provided that skilled man power and all necessary materials are available. Due to its economic and agro ecological importance, the improvement status of common bean should be boosted through sharing the responsibility of breeding system according to the agro ecology and preference criteria of the farmers. In addition to this, it is one of the major legume crops which bring foreign currency to the country and thus the common bean crop improvement system has to be encouraged by the higher officials more than what is being done now. Generally, gaps in knowledge of the respective working researchers and agricultural office extension workers, and facilities to undertake the breeding work need to be addressed in order to boost the effectiveness of common bean improvement in Ethiopia.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Berhanu Abate (PhD), Hawassa University College of Agriculture instructor, for edition of title before the article is being started to be written. Again my gratitude is to Yeyis Rezene (PhD student and molecular biologist) as he gave comments and corrections in the first draft of the article. The national lowland pulse crops improvement coordinator, Berhanu Amesalu Fenta (PhD), is highly acknowledged due to his support and encouragement. I would also like to appreciate Merkineh Mesene “Wolaita Sodo University Instructor’’ as he edited the English language after the article has been commented by the reviewers. My colleague Nadow Boto deserves gratitude for his valuable comments.

References

- FAO (Food and Agricultural Organization) (2016) Phaseolus bean post-harvest operations. Post-harvest compendium.

- Negash K, Genbeyehu S, Tumsa K, Habte E (2011) Enhancing progress and prospects with research and development of TLII in Ethiopia, 3rd ESA Annual Review & Planning Meeting, Lilongwe, Malawi.

- Akibode SC (2011) Trends in the Production, trade, and consumption of food-legume crops in sub-saharan africa. MSc thesis, Michigan State University.

- Asfaw A, Blair MW, Almekinders C (2009) Genetic diversity and population structure of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) landraces from the east africa highlands. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 120: 1-12.

- Jones PG, Thornton PK (2003) The potential impacts of climate change on maize production in africa and latin america in 2055. Global Environmental Change 13: 51-59.

- PABRA (Pan Africa Bean Research Alliance) (2014) Phase report and partnership in research for impact: case of common beans in ethiopia. Nairobi, Kenya.

- Habtu A, Sache I, Zadoks JC (1996) A survey of cropping practices and foliar diseases of common bean in ethiopia. Crop Protection 15: 179-186.

- Ma Y, Bliss FA (1978) Seed proteins of common bean. Crop Sci17: 431–437.

- Bliss FA, Brown JWS (1983) Breeding common bean for improved quantity and quality of seed protein. Plant Breed Rev 1: 59–102.

- Gepts P, Bliss FA (1984) Enhanced available methionine concentration associated with higher phaseolin levels in common bean seeds. Theor Appl Genet 69: 47–53.

- Asfaw A, Blair MW (2014) Quantification of drought tolerance in ethiopian common bean varieties. Agricultural Sciences 5: 124-139.

- CSA (Central Statistics Agency of Ethiopia) (2016) Report on area and crop production of major crops for 2016 Meher season, 1: 125.

- Habte E, Gebeyehu S, Tumsa S, Negash K (2014) Decentralized common bean seed production and delivery system. Melkassa agricultural research center, Ethiopian institute of agricultural research, Ethiopia.

- Gepts P (2001) Phaseolus vulgaris (Beans). Department of Agronomy and Range Science, University of California, Davis, USA.

- Lawrence K (2000) Beans, peas, and lentils. In: Kenneth FK (eds.) The Cambridge world history of food, Kriemhild Conee Ornelas, New York, Cambridge University Press, pp: 271-281.

- Gonzales AM, Rodino AP, Santalla M, DeRon AM (2009) Genetics of intra-gene pool and inter-gene pool hybridization for seed traits in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) germplasm from europe. Field Crops Research 112: 66-76.

- Cobley LS, Steele WM (1976) An introduction to the botany of tropical crops, Longman group Limited, London.

- Buruchara R (2007) Background information on common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L) in biotechnology, breeding & seed systems for african crops.

- Kelly DJ (2010) The story of bean breeding white paper prepared for bean CAP & PBG works on the topic of dry bean production and breeding research in the USA.

- Jones LA (1999) Phaseolus bean: post-harvest operations. Centro International de Agriculture Tropical (CIAT).

- Freytag G, Debouck DG (2002) Taxonomy, distribution and ecology of the genus Phaseolus (Leguminosae-Papilionoideae) in north america, Mexico and Central America. Botanical Institute of Texas, United States, p: 300.

- Dev J, Gupta VP (1997) Common bean historic view and breeding strategy. Annals of Biology 13: 213 - 219.

- Abebe G, Fininsa C, Tesso T, Rahman AMT (2005) Participatory bean breeding with women and small holder farmers in eastern ethiopia. World Journal of Agricultural Sciences 1: 28-35.

- Mekonnen F (2007) Haricot ban (Phaseolus Vulgaris L.) variety development in the lowland areas of Wollo. 2nd Annual Regional Conference on Completed Crops Research Activities, Ethiopia, pp. 86-93.

- Kay DE (1979) Food legumes. Tropical product institutes. 56/62 Gray’s lnn Road London.

- Negash R (2007) Determinants of adoption of improved haricot bean production package in alaba special woreda, Southern ethiopia. MSc Thesis, school of graduate studies of haramaya university.

- FiBL (2011) Research institute of organic agriculture, african organic agriculture training manual. A resource manual for trainers. Switzerland.

- EPPA (Ethiopian Pulses Profile Agency) (2004) Ethiopian export promotion agency product development & market research directorate ethiopia, Addis Ababa.

- Legese D, Kummsa G, Teshale A (2006) Production and marketing of white pea beans in rift valley Ethiopia. A sub sector analysis CRS-Ethiopia program, Addis Ababa.

- Ferris S, Kaganzi E (2008) Evaluating marketing opportunities for haricot beans in Ethiopia. IPMS (Improving Productivity and Market Success) of Ethiopian Farmers Project Working Paper 7. ILRI (International Livestock Research Institute), Nairobi, Kenya, p: 68.

- Ferris RSB, Robbins P (2004) Developing marketing information services in eastern Africa: Local, national and regional market information–intelligence services.

- CIAT (International Center for Tropical Agriculture) (2008) Highlights CIAT in Africa. New bean varieties for ethiopian farmers. Africa coordination kawanda agricultural research institute Kampala, Uganda.

- Teshale A, Habru A, Paul k (2003) Development of improved haricot bean germplasm for the mid and low-altitude sub humid agro-ecologies of Ethiopia. Melkassa Agricultural Research Center. Nazareth, Ethiopia, Nairobi University, Nairobi, Kenya.

- Â Ashok KM, Indu, Chandrawat KS (2016) Gene pyramiding: An overview. Int J Curr Res Biosci Plantbiol 3: 22-28.

- Tumsa K, Negash K, Amsalu B, Ayana G, Rezene Y, et al. (2015) Resistance breeding against major disease of common bean in Ethiopia. EIAR (Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research), NBRP (National Bean Research Program).

- Anderson MS, Saltzman A, Virk PS, Feiffer WHP (2017) Progress Update: crop development of bio fortified staple food crops under harvest plus. Afr J Food Agric Nutr Dev 17: 11905-11935.

- Voysest O, Valencia MC, Amezquita MC (1994) Genetic diversity among latin american andean and mesoamerican common bean cultivars. Crop Sci 34: 1100-1110.

- Miklas (2000) Use of phaseolus germplasm in breeding pinto, great northern, pink and red bean for Pacific northwest and intermountain region, pp: 13-29.

- Bassett MJ, McClean PE (2010) A brief review of the genetics of partly colored seed coats in common bean. Annu Rep Bean Improv Coop 43: 99–100.

Citation: Demelash BB (2018) Common Bean Improvement Status (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) in Ethiopia. Adv Crop Sci Tech 6: 347. DOI: 10.4172/2329-8863.1000347

Copyright: © 2018 Demelash BB. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 11093

- [From(publication date): 0-2018 - Nov 14, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 9196

- PDF downloads: 1897