Research Article Open Access

Clinico-Pathological Evaluation and Correlation of Stages of Oral Submucous Fibrosis with Different Habits

Shweta Singh1, Pravin Gaikwad2, Gaurav Sapra3 and Raju Chauhan4*

1Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Saraswati Dental College and Hospital, Lucknow, India

2Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Mansarovar Dental College, Bhopal, India

3Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Institute of dental sciences, Lucknow, India

4Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Saraswati Dental College and Hospital, Lucknow, India

- Corresponding Author:

- Raju Chauhan

Reader, Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics

Saraswati Dental College and Hospital

Tiwariganj, Faizabad Road

Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India

Pin- 227105

Tel: +91-99-56-329131

E-mail: rchauhan_1978@rediffmail.com

Received Date: January 16, 2015; Accepted Date: February 16, 2015; Published Date: February 23, 2015

Citation: Shweta Singh, Pravin Gaikwad, Gaurav Sapra, Raju Chauhan (2015) Clinico-Pathological Evaluation and Correlation of Stages of Oral Submucous Fibrosis with Different Habits. J Interdiscipl Med Dent Sci 3:175. doi: 10.4172/2376-032X.1000175

Copyright: ©2015 Abraham and Pullishery. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited

Visit for more related articles at JBR Journal of Interdisciplinary Medicine and Dental Science

Abstract

Objective: Oral Submucous Fibrosis (OSF) is a precancerous condition and is mainly associated with the chewing of areca nut. This study was undertaken to correlate the etiological factors (duration, frequency, style and chewing habit) associated with OSF with clinical grading and histological staging.

Methodology: A total of 50 clinically and histopathologically diagnosed cases of OSF were included in the study. Detailed clinical examination of each patient was done; emphasizing on their habit. Clinical grading and histological staging of each case was done and the data was recorded in a prescribed format. Statistical analysis was done using chi-square test.

Result and observation: A total of 50 subjects were studied, with a male to female ratio of 7.3:1 with age range of 20-30 year. Gutkha-chewing habit alone was identified in 46% of subjects and those associated with gutkha and tobacco were 33.3% with a mean ± S.D =32 ± 11.51.

Conclusion: The widespread habit of chewing gutkha plays a major role in the development of Oral Submucous Fibrosis than any other habit. The duration and frequency of its use and type of areca nut product has effect on the incidence and severity of OSF.

Keywords

World Trade Center, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), 9/11, human remains

Abbreviations

World Trade Center (WTC), New York City Police Department (NYPD), Fire Department of New York City (FDNY), Department of Sanitation of New York City (DSNY), Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), Staten Island (SI)

Introduction

The World Trade Center (WTC) attack on September 11, 2001 (9/11) resulted in the deaths of nearly 3,000 individuals (Vlahov et al., 2002). The 16 acres of land on which the WTC Twin Towers stood became a crime scene for the investigation one of the largest acts of terrorism in the United States (Mackinnon & Mundorff, 2007). An estimated 91,000 WTC rescue/recovery workers were exposed to dust and debris from the collapsed buildings (Murphy et al., 2007) and possibly human remains, particularly during the removal and sifting of thousands of tons of debris for recovery of human remains and personal effects (Ekenga et al., 2011; Farfel, DiGrande, & Brackbill, 2008; Murphy, 2006; Perrin et al., 2007; Vlahov et al., 2002).

Between September 12, 2001 and July 31, 2002, over 1.8 million tons of debris from the WTC site (Ground Zero) were transported by truck to lower Manhattan piers and then loaded onto barges for transfer to the Staten Island (SI) Fresh Kills Landfill (landfill) for processing as a part of the recovery efforts and criminal investigation (Mackinnon & Mundorff, 2007). The Office of the Chief Medical Examiner for the City of New York (OCME) was tasked with sorting through an estimated 54,000 personal effects and over 20,000 human remains, resulting in the identification of 59% of the victims (Bowler et al., 2012; Goldenberg, 2015; New York State Museum, 2004; WTC Operational Statistics, 2015).

SI workers were exposed to debris which contained not only pulverized matter from the collapse of the WTC buildings (Brackbill, Thorpe, DiGrande, & Perrin, 2006; Landrigan et al., 2004; Lioy et al., 2002) but hazardous waste, chemicals, and microorganisms already present at the landfill, a former 3,000-acre NYC garbage disposal site that was closed prior to 9/11 (Anatomy: World Trade Center/Staten Island Landfill Recovery Operation, 2004; Dawsey, 2013; Gelberg, 1997; Suflita et al., 1992). While work at the landfill was performed by personnel of the New York City (NYC) Police Department (NYPD), NYC Fire Department (FDNY), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and OCME, most of whom likely had prior training or experience in human remains recovery work, large numbers of workers not likely to have had this type of training or experience also participated in this painstaking work, including NYC Department of Sanitation (DSNY) personnel, construction workers, and volunteers affiliated with organizations (e.g., Red Cross) (Debchoudhury et al., 2011; Ekenga et al., 2011).

Previous research has shown that adverse mental health consequences, particularly posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), have been associated with exposure to human remains during war time, and following natural disasters, plane crashes and other events (Andersen, Christensen, & Petersen, 1991; Bartone, Ursano, Wright, & Ingraham, 1989; McCarroll et al., 1995; Miles, Demi, & Mostyn-Aker, 1984; Steinglass & Gerrity, 1990; Ursano, Fullerton, Kao, & Bhartiya, 1995). PTSD has been found to be elevated in 9/11 rescue, recovery and clean-up workers (North et al., 2002; Perrin et al., 2007). This raise may be due to the nature of work performed during or after a disaster. In a study of over 8,000 WTC police responders, Pietrzak et al., found that exposure to human remains was associated with an increased likelihood of PTSD (Pietrzak et al., 2012). There is limited research regarding the extent to which encountering human remains after the WTC disaster may have resulted in lasting psychological effects.

There is a particular gap in the literature regarding the effects of human remains exposure on SI landfill and barge workers who were engaged in intensive debris handling and sorting activities after 9/11. This study examined the self-reported exposure to human remains among those who worked at the SI landfill and barges in order to assess the possible impact on PTSD among these workers more than 10 years after 9/11.

Methods

The methods used to collect World Trade Center Health Registry (WTCHR or Registry) data have been previously published (Brackbill et al., 2009; Farfel, DiGrande, & Brackbill et al., 2008; Murphy, 2006; Perrin et al., 2007). Briefly, the 71,431 individuals enrolled in the Registry comprise several eligibility groups: Rescue, recovery and clean-up workers and volunteers; lower Manhattan workers and passersby on 9/11; lower Manhattan residents; and school children and school staff. Enrollees were recruited from lists that were provided by employers or governmental agencies (30%) and through public outreach (70%) (Farfel, DiGrande, & Brackbill, 2008). Three waves of surveys were distributed to participants; Wave 1 (2003-04); Wave 2 (2006-07) and Wave 3 (2011-12). Data were collected via paper, computer assisted telephone interviews (CATI), in-person interviews, or web-based surveys. The Registry protocol and subsequent sub-studies were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

The initial lack of data on the health effects of working on the landfill and barges led to a two-phase investigation focusing on the unique experiences and exposures of SI landfill and barge workers enrolled in the Registry. Phase I was a qualitative study in 2009 which was designed to investigate the 9/11-related experiences and exposures of SI workers (Ekenga et al., 2011). Findings from Phase

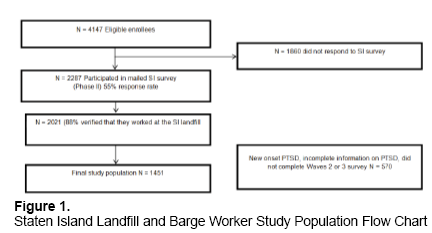

I were used by the investigators to develop Phase II, an in-depth sub-group survey in the context of the ongoing Registry prospective cohort study. The Phase II survey assessed prior disaster experience or training, tasks performed at landfill or barge sites, use of protective equipment, site-specific experiences, and current employment status for all enrollees who reported having worked on the SI landfill or barges. The survey was distributed via mail from June 2010 to November 2011 to 4,147 SI workers, with a response rate of 55% (n = 2,287).

Study Variables

Primary Outcomes

Persistent posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

PTSD was measured at all three waves using a 9/11-specific PTSD Checklist (PCL), a validated tool which measures self-reported symptoms of PTSD in the past 30 days. The PCL is a tool that is widely used to assess self-reported data regarding PTSD symptomology. Symptoms are event-specific as related to 9/11 and have been previously used in Registry studies of PTSD (Perrin et al., 2007). The PCL includes 17-items scored on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely), with summed scores ranging from 17 to 85 (Blanchard, Jones-Alexander, Buckley, & Forneris, 1996; Weathers et al., 1993). Probable PTSD was defined as meeting a cutoff score of 44 on the PCL, as well as meeting the following criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition (DSM-IV): at least one re-experiencing symptom (DSM-IV criterion B), three avoidance symptoms (DSM-IV criterion C), and two hyperarousal symptoms (DSM-IV criterion D) (Smith et al., 1999). The PCL has relatively high levels of sensitivity (94%-97%) and specificity (86%-99%) as well as positive predictive value (70%-97%) (Blanchard, Jones-Alexander, Buckley, & Forneris, 1996; Ruggiero, Ben, Scotti, & Rabalais, 2003; Ventureyra et al., 2001; Weathers, et al., 1993). Blanchard has reported that the PCL ≥ 44 cutoff provides the highest level of diagnostic efficiency at 0.94 (Blanchard, Jones-Alexander, Buckley, & Forneris, 1996). Persistent PTSD was defined as having met the PTSD criteria detailed above at either W1 or W2 and at W3.

Additional Study Variables

Staten Island exposure scale and other work-related variables

In order to measure the cumulative effects of SI-specific working conditions and exposures after 9/11, we created a work exposure scale consisting of seven questions grouped into three categories of exposures: 1) visual (seeing dust in the air and impaired visibility), 2) respiratory (breathing in dust from the debris piles, construction activities, sorting activities, or unpaved roads, breathing in diesel or gasoline fumes, and breathing in garbage odors), and 3) protective measures (wearing a Tyvek suit, Nomex suit, or any other disposable protective suit, and use of shower facilities) that were analyzed in the aggregate. This scale was based on the findings from the Phase I survey and our analysis found the scale to have good reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.84). The possible responses for all questions were: every day, almost every day, some days, almost never, and never. These responses were scored from 4 (every day) to 0 (never) except those regarding wearing a disposable suit or using a shower facilities at the worksite which, due to their protective nature, were given the reverse score of 0 (every day) to 4 (never). The aggregated scores ranged from 0-28. We classified the workers’ scores into low (0-19), and high (20-28) exposures based on the median score. Additional work-related characteristics were: having worked on the pile at Ground Zero, which was reported at W1, and having prior disaster training or experience.

Exposure to human remains

The frequency of an enrollee’s exposure to human remains was asked in a separate question: ‘How often did you encounter human remains at your worksite?’ The responses to this question ranged from never to every day.

Social support

An abbreviated version of the Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey (Ritvo et al., 1997; Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991), asked at W3, was used to assess the impact of social support on persistent PTSD. The social support scale measured the frequency of how often an enrollee has someone available to take them to the doctor, have a good time with them, hug them, prepare meals for them, and understand their problems. This scale has been used in previous Registry studies, and has been shown to be a predictor of unmet mental health care needs among WTCHR enrollees with PTSD or depression (Brackbill, et al., 2009; Brackbill et al., 2013; Ghuman et al., 2014). Each of the five social support questions’ responses was scored from 0 (none of the time) to 4 (all of the time). The five individual scores were summed and categorized as: very high social support (16 to 20); high social support (12 to 15); medium social support (7 to 11); and low or no social support (0 to 6).

Study Population

On the Registry’s W1 survey, a total of 4,490 workers reported that they worked at the SI landfill or barges, which had to include at least one shift between September 12, 2001 to July, 26, 2002 on a pier in lower Manhattan or on Staten Island, at the World Trade Center Recovery Operation on Staten Island located at the Fresh Kills Landfill, Staten Island, NY, or on at least one of the NYC Department of Sanitation barges or trucks used to transport debris between the WTC site and the WTC Recovery Operation on Staten Island. In our analysis, we excluded workers who were less than 18 years of age at October 20, 2010 (n = 7), non-English speakers (n = 36), and those who did not consent to future studies (n = 300), which left 4,147 enrollees who were eligible for Phase II

A total of 2,287 out of 4,147 (55%) eligible enrollees completed the Phase II SI survey. Compared to survey non-participants, participants who completed the survey were more likely to be: older; non-Hispanic; married and have a higher income and level of education. Of these, 2,021 (88%) verified that they had worked at either the landfill or on the piers or barges. Only participants who completed both the Waves 2 and 3 follow-up surveys were included (n = 1,592) in order to assess the persistence of the outcome of interest. We excluded those who screened positive for PTSD for the first time at W3 (n = 66) in order to rule out new-onset, rather than persistent, PTSD, those missing information on PTSD at Wave 3 (n = 69), and those with incomplete information on PTSD at prior waves (n = 6). The final analytic sample consisted of 1,451 enrollees (Figure 1).

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (Cary, N.C.). We conducted bivariate analyses, using chi-square tests of independence, to examine the characteristics of our study population, comparing those with persistent PTSD to those without. A logistic regression model, adjusted for age, sex, Hispanic ethnicity, education, occupation, having worked on the pile at Ground Zero, and social support, assessed the association between human remains exposure and other SI work exposures and persistent PTSD in order to examine the cumulative effects of adverse physical exposures at the worksite along with the increased frequency of exposure to human remains.

Results

Characteristics of Study Population

Staten Island survey participants were primarily male (85.3%), age 45 years and older at the time of the W3 survey (82.0%) and had more than a high school education at W1 (69.0%). Almost half (47.8%) of participants reported also working on the pile at Ground Zero. The largest proportion of respondents worked for NYPD (29.5%), followed by DSNY with 16.3%, and FDNY with 11.9%. Overall, 108 workers (7.4%) met the case definition for persistent PTSD (Table 1). FDNY, DSNY and NYPD workers were almost exclusively male (100%, 99%, and 89%, respectively) (Data not shown).

| Total | Persistent PTSD at W3* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N=1592 n (%) | Yes n (%) | P-Value | |

| Total | 1592 (100) | 108 (7.4) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1358 (85.3) | 100 (8.1) | 0.02 |

| Female | 234 (14.7) | 8 (3.7) | |

| Age at Wave 3 | |||

| [25-44] | 287 (18.0) | 15 (5.7) | 0.23 |

| 45+ | 1305 (82.0) | 93 (7.8) | |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | |||

| Yes | 135 (8.5) | 14 (11.6) | 0.07 |

| No | 1455 (91.4) | 93 (7.0) | |

| Education at Wave 1 | |||

| High School or less | 490 (30.8) | 45 (10.2) | 0.01 |

| More than High School | 1098 (69.0) | 63 (6.3) | |

| Encountered Human Remains | |||

| Every day | 161 (10.1) | 19 (13.3) | <0.0001 |

| Almost Every day | 130 (8.2) | 14 (11.7) | |

| Some days | 545 (34.2) | 46 (9.5) | |

| Almost Never | 231 (14.5) | 16 (7.3) | |

| Never | 492 (30.9) | 11 (2.4) | |

| Disaster training and or experience | |||

| Yes | 753 (47.3) | 46 (6.5) | 0.21 |

| No | 812 (51.0) | 59 (8.2) | |

| Staten Island Exposure Scale ** | |||

| [20-28] | 753 (47.3) | 88 (12.1) | <0.0001 |

| [0-19] | 820 (51.5) | 19 (2.7) | |

| Social Support at Wave 3 | |||

| [0-6] least | 111 (7.0) | 19 (19.6) | <0..0001 |

| [7-11] | 192 (12.1) | 23 (13.9) | |

| [12-15] | 358 (22.5) | 37 (11.6) | |

| [16-20] most | 895 (56.2) | 26 (3.1) | |

| Worked on the pile at Ground Zero | |||

| Yes | 761 (47.8) | 72 (10.6) | <0.0001 |

| No | 831 (52.2) | 36 (4.7) | |

| Occupation*** | |||

| NYPD | 469 (29.5) | 25 (5.7) | 0.001 |

| FDNY | 189 (11.9) | 21 (12.6) | |

| DSNY | 259 (16.3) | 26 (11.5) | |

| Other | 675 (42.4) | 36 (5.8) | |

* Persistent PTSD is defined as a total PCL score ≥ 44 and meeting the DSM-IV criteria at Wave 3 in addition to meeting a total PCL score ≥ 44 and DSM-IV criteria at either Wave 1 or Wave 2

** The Staten Island (SI) Exposure scale measures the cumulative effects of SI exposures for recovery and clean-up workers after 9/11. The scale’s seven survey questions measured both worksite exposures and protective measures. Responses were scored from 4 to 0, with protective questions receiving a reverse score of 0-4. Each individual question score was combined into a cumulative score of low (0-19) and high (20-28) exposures.

*** FDNY: New York City Fire Department; DSNY: The City of New York Department of Sanitation; NYPD: New York City Police Department

Table 1: Characteristics of Staten Island Barge and Landfill Recovery and Clean-up workers and Persistent PTSD

Factors Associated with Persistent PTSD among S.I. Workers

Encountering human remains was significantly associated with persistent PTSD; 13.3% of those who encountered human remains every day had persistent PTSD compared to 2.4% of those who reported never encountering human remains. Factors significantly associated with persistent PTSD in bivariate analyses included male gender, having high school or lower educational level, working on the pile at Ground Zero, a high score on the Staten Island Exposure Scale, and low social support. Having prior disaster training or experience was not associated with persistent PTSD in bivariate analysis. Prevalence of persistent PTSD was highest in sanitation workers (11.5%), and lowest in police (5.7%) (Table 1).

DSNY and FDNY workers had higher odds of persistent PTSD than those affiliated with the NYPD, even after controlling for exposure and disaster training. Lower social support was associated with higher odds of persistent PTSD (Table 2). Hispanic ethnicity and having a high school or lower educational level were also strong predictors of persistent PTSD. Age and sex were not associated with persistent PTSD in the adjusted model.

| AOR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Social Support at W3 | ||

| 1 (least) | 7.66 | 3.77-15.54 |

| 2 | 4.13 | 2.19-7.79 |

| 3 | 4.24 | 2.44-7.36 |

| 4 (most) | 1.0 | |

| Occupation*** | ||

| NYPD | 1.0 | |

| FDNY | 2.46 | 1.20-5.04 |

| DSNY | 2.52 | 1.25-5.07 |

| Other | 1.61 | 0.89-2.92 |

| Encountered Human Remains | ||

| Every day | 4.77 | 2.00-11.52 |

| Almost every day | 4.35 | 1.75-10.80 |

| Some days | 2.98 | 1.43-6.22 |

| Almost never | 2.24 | 0.96-5.19 |

| Never | 1.0 | |

| Staten Island Exposure Scale+ | ||

| 0-19 | 3.38 | 1.93-5.90 |

| 20-28 | 1.0 |

* Model adjusted for sex, age group, Hispanic ethnicity, education, and working on the pile at Ground Zero social support, occupation, frequency of encountering human remains, and the Staten Island Exposure Scale.

** Persistent PTSD is defined as a total PCL score ≥ 44 and meeting the DSM-IV criteria at Wave 3 in addition to meeting a total PCL score ≥ 44 and DSM-IV criteria at either Wave 1 or Wave 2

*** FDNY: New York City Fire Department; DSNY: The City of New York Department of Sanitation; NYPD: New York City Police Department

+ The Staten Island (SI) Exposure scale was created in order to measure the cumulative effects of SI exposures for recovery and clean-up workers after 9/11. The scale’s seven survey questions measured both worksite exposures and protective measures. Responses were scored from 4 to 0, with protective questions receiving a reverse score of 0-4. Each individual question score was combined into a cumulative score of low (0-19) and high (20-28) exposures.

Table 2: Multivariable logistic regression model* of the association between encountering human remains and other landfill exposures and persistent PTSD** among Staten Island Barge and Landfill Recovery and Clean-up workers

A dose-response relationship was found between frequency of human remains exposure and persistent PTSD (adjusted odds ratio (AOR): every day = 4.77; 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.00-11.52, almost every day AOR = 4.35; 95% CI: 1.75-10.80), and some days AOR = 2.98; 95% CI: 1.43-6.22). When compared to workers with the lower SI exposure scores, those with highest exposure had more than three times to the odds of having persistent PTSD (AOR: 3.38; 95% CI: 1.93-5.90) (Table 2).

Discussion

Staten Island landfill and barge debris removal work terminated on July 26, 2002, yet exposure to human remains and other SI landfill and barge-specific exposures from this work were found to be strong predictors of PTSD 10-11 years later. Similar to other studies of 9/11-affected populations, Hispanic ethnicity and having a high school or lower educational level were also found to be strong predictors of persistent PTSD (Bowler et al., 2012; DiGrande et al., 2008; Galea et al., 2002). Adverse mental health consequences, particularly PTSD, have been associated with exposure to human remains during wartime, peacekeeping missions, disasters, and other events that have resulted in casualties (Andersen, Christensen, & Petersen, 1991; Bartone, Ursano, Wright, & Ingraham, 1989; Green, Lindy, Grace, & Gleser, 1989; McCarroll, Ursano, & Fullerton, 1995; Miles, Demi, & Mostyn-Aker, 1984; Steinglass & Gerrity, 1990; Stellman et al., 2008; Sutker et al., 1994; Ursano, Fullerton, Kao, & Bhartiya, 1995). One-third of recovery personnel evaluated 20-months after a DC10 plane crash on Mount Erebus, Antarctica, resulting in 257 deaths, were found to have immediate physiological symptoms including anxiety, depression, increased tension, sleep disturbance, or intrusive memories (Taylor & Frazer, 1982). A study done on disaster assistance workers after the December 12, 1985 crash of an airliner with 248 soldiers on a peacekeeping mission found a dose-response relationship between degree of exposure to human remains and psychological distress six and twelve months post-disaster (Bartone, Ursano, Wright, & Ingraham, 1989). Workers who spent extended periods of time with families during body identification experienced negative psychological health outcomes similar to those found in our study (Bartone, Ursano, Wright, & Ingraham, 1989. Anticipated contact with human remains has also been shown to increase psychological distress (Keller & Bobo, 2002; McCarroll, Ursano, & Fullerton, 1995).

Rescue and recovery workers may be traumatized by the experience or expectation of encountering human remains following disasters, particularly if they are enlisted from ranks of workers and other volunteers who have little or no training or experience in tasks that may expose them to human remains (Ursano & McCarroll, 1990). Workers with the DSNY and FDNY were more likely to have persistent PTSD compared to NYPD workers, even after controlling for demographic variables and prior disaster training or experience. In contrast to other studies, (McCarroll, Ursano, & Fullerton, 1995; Perrin et al., 2007) we found that workers’ reported prior training or disaster experience did not play a role in their risk for PTSD in the adjusted analyses. Others have reported that even well-trained professionals may experience clinically-significant symptoms after exposure to dead bodies (Ursano & Hermsen, 1996). Perrin et al. found that 9/11 responders who performed tasks atypical to their usual occupation demonstrated a greater risk for PTSD, with the strongest relationship among construction and sanitation workers (Perrin et al., 2007). Our finding may be explained in part by the fact that DSNY and FDNY workers, unlike NYPD workers, likely performed 9/11-related tasks that were atypical of their routine tasks. In particular, DSNY workers typically do not have the training or experience to deal with encountering human remains.

Our finding of a significant protective effect of social support in relation to persistent PTSD is consistent with other Registry studies (Brackbill et al., 2009). Pietrzak’s (2013) study of police responders to 9/11, and other research has shown that social support may aid in the handling of stressful events (Bassuk, 1991; Cohen & Wills, 1985; Galea et al., 2002; Pietrzak et al., 2013). Reissman et al noted that pre-disaster assessments of workers who may be involved in any aspect of disaster work may identify individuals who are at higher risk for mental health illness (Reissman & Howard, 2008). Over twenty years ago, McCarroll et al., recommended strategies for disaster preparedness and response that remain useful, including providing: pre-briefing and training on specific tasks; breaks; adequate time for sleep and rest; and regular time off (McCarroll, Ursano, Wright, & Fullerton, 1993). They further suggested that post-work transition periods and embedding mental health professionals to assist with the immediate needs of responders may also help. Importantly, screening responders for early identification of PTSD and referral to evidence-based treatment can help prevent long-term illness. Lastly, increasing levels of spouse and co-worker involvement and providing other sources of social support may also help reduce PTSD among responders following disasters (McCarroll, Ursano, Wright, & Fullerton, 1993).

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study include its large sample size, and the ability to look at long-term health outcomes, as the cohort was followed longitudinally for over 10 years. Another strength of this quantitative study is that it was informed and guided by the results of the qualitative phase.

One limitation of this study is that it relied on self-reported exposure information collected over 8 years after the attacks, which may be subject to recall bias. The term “human remains” may be broadly interpreted, and the survey did not distinguish between human remains and personal effects of victims. Further research will be needed to investigate whether there is differential impact of encountering human remains versus personal effects. Despite these limitations, the Phase I interviews, focus groups and subsequent Phase II survey have led to better delineation and understanding of the tasks performed at SI, including prior disaster experience and training, location of work on or after 9/11, the frequency of the exposure to human remains and the aggregated responses to the SI Exposure Scale: breathing in dust from the debris piles, construction activities, sorting activities, unpaved roads; seeing dust in the air; impaired visibility; breathing in diesel or gasoline fumes; breathing in garbage odors; wearing a Tyvek suit, Nomex suit, or any other disposable protective suit; and use of shower facilities

Conclusions

We found that Staten Island workers who were frequently exposed to human remains during clean-up work after 9/11 had an increased risk of developing persistent PTSD. Our findings highlight the ongoing need for strategies to prevent adverse mental health outcomes associated with exposure to human remains post-disaster. Potential interventions include pre-briefing and training workers to handle human remains before participating in disaster response; embedding mental health professionals to provide ongoing psychological support during such a response effort; and conducting prompt screening for PTSD and referral to evidence-based treatment after the response.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Margaret Millstone, Steven D. Stellman, and Howard Alper from the New York City Department of Health and Barbara Butcher from the New York City Office of Chief Medical Examiner for their time and expertise in the development and review of this manuscript. This work was supported by Cooperative Agreement Numbers 2U50OH009739 and 1U50OH009739 from CDC-NIOSH, and U50/ATU272750 from CDC-ATSDR, which included support from CDC-NCEH and the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (NYC DOHMH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of CDC.

References

- Anatomy: World Trade Center/Staten Island Landfill Recovery Operation. (2004). Phillips Jordan Inc. Disaster Recovery Group.

- Andersen, H.S., Christensen, A.K., & Petersen, G.O. (1991). Post-traumatic stress reactions amongst rescue workers after a major rail accident. Anxiety Research, 4(3), 245-251.

- Bartone, P.T., Ursano, R.J., Wright, K.M., & Ingraham, L.H. (1989). The impact of a military air disaster on the health of assistance workers: A prospective study. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 177(6), 317-328.

- Bassuk, E. (1991). Prevalence of somatic and psychiatric disorders among former prisoners of war. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 42(8), 807.

- Blanchard, E.B., Jones-Alexander, J., Buckley, T.C., & Forneris, C.A. (1996). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34(8), 669-673.

- Bowler, R.M., Harris, M., Li, J., Gocheva, V., Stellman, S.D., Wilson, K., et al. (2012). Longitudinal mental health impact among police responders to the 9/11 terrorist attack. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 55(4), 297-312.

- Brackbill, R., Hadler, J., DiGrande, L., Ekenga, C., & Farfel, M. (2009). Asthma and posttraumatic stress symptoms 5 to 6 years following exposure to the World Trade Center terrorist attack. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association, 302(5), 502-516.

- Brackbill, R., Stellman, S., Perlman, S., Walker, D., & Farfel, M. (2013). Mental health of those directly exposed to the World Trade Center disaster: Unmet mental health care need, mental health treatment service use, and quality of life. Social Science & Medicine, 81(0), 110-114.

- Brackbill, R., Thorpe, L., DiGrande, L., & Perrin, M. (2006). Surveillance for World Trade Center disaster health effects among survivors of collapsed and damaged buildings. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Surveillance summaries (Washington, DC: 2002), 55(2), 1-18.

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T.A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological bulletin, 98(2), 310.

- Dawsey, J. (2013). New Efforts to Sift for 9/11 Remains. The Wall Street Journal.

- Debchoudhury, I., Welch, A.E., Fairclough, M.A., Cone, J.E., Brackbill, R.M., Stellman, S.D., et al. (2011). Comparison of health outcomes among affiliated and lay disaster volunteers enrolled in the World Trade Center Health Registry. Preventive Medicine, 53(6), 359-363.

- DiGrande, L., Perrin, M., Thorpe, L., Thalji, L., Murphy, J., Wu, D., et al. (2008). Posttraumatic stress symptoms, PTSD, and risk factors among lower Manhattan residents 2-3 years after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21(3), 264-273.

- Ekenga, C.C., Scheu, K.E., Cone, J.E., Stellman, S.D., & Farfel, M.R. (2011). 9/11-Related Experiences and Tasks of Landfill and Barge Workers: Qualitative Analysis from the World Trade Center Health Registry. BMC public health, 11(1), 321.

- Farfel, M., DiGrande, L., & Brackbill, R. (2008). An Overview of 9/11 Experiences and Respiratory and Mental Health Conditions among World Trade Center Health Registry Enrollees. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine.

- Galea, S., Ahern, J., Resnick, H., Kilpatrick, D., Bucuvalas, M., Gold, J., et al. (2002). Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. New England Journal of Medicine, 346(13), 982-987.

- Galea, S., Resnick, H., Ahern, M.J., Gold, J., Bucuvalas, M., Kilpatrick, D., et al. (2002). Posttraumatic stress disorder in Manhattan, New York City, after the September 11th terrorist attacks. Journal of Urban Health, 79(3), 340-353.

- Gelberg, K. (1997). Health study of New York City department of sanitation Landfill employees. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 39(11), 1103-1110.

- Ghuman, S., Brackbill, R., Stellman, S., Farfel, M., & Cone, J. (2014). Unmet mental health care need 10-11 years after the 9/11 terrorist attacks: 2011-2012 results from the World Trade Center Health Registry. BMC public health, 14(1), 491.

- Goldenberg, G. (2015). Speaking for the dead, caring for the living. NYU Physician, 19-21.

- Green, B.L., Lindy, J.D., Grace, M.C., & Gleser, G.C. (1989). Multiple Diagnosis in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. The Role of War Stressors. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 177(6), 329-335.

- Keller, R., & Bobo, W. (2002). Handling human remains following the terrorist attack on the Pentagon: experiences of 10 uniformed health care workers. Military medicine, 167(9), 8.

- Landrigan, P.J., Lioy, P.J., Thurston, G., Berkowitz, G., Chen, L.C., Chillrud, S.N., et al. (2004). Health and environmental consequences of the world trade center disaster. Environmental Health Perspectives, 112(6), 731-739.

- Lioy, P.J., Weisel, C.P., Millette, J.R., Eisenreich, S., Vallero, D., Offenberg, J., et al. (2002). Characterization of the dust/smoke aerosol that settled east of the World Trade Center (WTC) in lower Manhattan after the collapse of the WTC 11 September 2001. Environmental health perspectives, 110(7), 703.

- Mackinnon, G., & Mundorff, A. (2007). The World Trade Center-September 11, 2001. Forensic Human Identification: An Introduction. BAHID, CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group, 485-499.

- McCarroll, J.E., Ursano, R.J., & Fullerton, C.S. (1995). Symptoms of PTSD following recovery of war dead: 13–15-month follow-up. The American journal of psychiatry. 152(6), 939-941

- McCarroll, J.E., Ursano, R.J., Fullerton, C.S., Oates, G.L., Ventis, W.L., Friedman, H., et al. (1995). Gruesomeness, emotional attachment, and personal threat: dimensions of the anticipated stress of body recovery. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 8(2), 343-349.

- McCarroll, J.E., Ursano, R.J., Wright, K.M., & Fullerton, C.S. (1993). Handling bodies after violent death: Strategies for coping. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 63(2), 209-214

- Miles, M.S., Demi, A.S., & Mostyn-Aker, P. (1984). Rescue workers' reactions following the Hyatt Hotel disaster. Death Education, 8(5-6), 315-331.

- Murphy, J. (2006). Tower Tales - Hoping to make buildings safter, scientists want to talk to WTC survivors. Village Voice.

- Murphy, J., Brackbill, R., Thalji, L., Dolan, M., Pulliam, P., & Walker, D. (2007). Measuring and maximizing coverage in the World Trade Center Health Registry. Statistics in Medicine, 26(8), 1688-1701.

- New York State Museum. (2004). Recovery: The World Trade Center Recovery Operation at Fresh Kills. Retrieved May 15, 2015, from http://www.nysm.nysed.gov/exhibits/traveling/recovery/documents/RecBro.pdf

- North, C.S., Tivis, L., McMillen, J.C., Pfefferbaum, B., Spitznagel, E.L., Cox, J., et al. (2002). Psychiatric disorders in rescue workers after the Oklahoma City bombing. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(5), 857-859.

- Perrin, M., DiGrande, L., Wheeler, K., Thorpe, L., Farfel, M., & Brackbill, R. (2007). Differences in PTSD prevalence and associated risk factors among World Trade Center disaster rescue and recovery workers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(9), 1385-1394.

- Pietrzak, R., Schechter, C., Bromet, E., Katz, C., & Reissman, D. (2012). The burden of full and subsyndromal posttraumatic stress disorder among police involved in the World Trade Center rescue and recovery effort. Journal of psychiatric research, 46(7), 835-842.

- Pietrzak, R.H., Feder, A., Singh, R., Schechter, C.B., Bromet, E.J., Katz, C.L., et al. (2013). Trajectories of PTSD risk and resilience in World Trade Center responders: an 8-year prospective cohort study. Psychological Medicine, 44(1), 205-219.

- Reissman, D.B., & Howard, J. (2008). Responder safety and health: Preparing for future disasters. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine: A Journal of Translational and Personalized Medicine, 75(2), 135-141.

- Ritvo, P., Fischer, J., Miller, D., Andrews, H., Paty, D., & LaRocca, N. (1997). Multiple sclerosis quality of life inventory: A User's manual. New York: National Multiple Sclerosis Society, 1-65.

- Ruggiero, K., Ben, K., Scotti, J., & Rabalais, A. (2003). Psychometric Properties of the PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16(5), 495-502.

- Sherbourne, C.D., & Stewart, A.L. (1991). The MOS social support survey. Social Science & Medicine, 32(6), 705-714.

- Smith, M.Y., Redd, W., DuHamel, K., Vickberg, S.J., & Ricketts, P. (1999). Validation of the PTSD checklist-civilian version in survivors of bone marrow transplantation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 12(3), 485-499.

- Steinglass, P., & Gerrity, E. (1990). Natural Disasters and Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Short-Term versus Long-Term Recovery in Two Disaster-Affected Communities. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 20(21), 1746-1765.

- Stellman, J.M., Smith, R.P., Katz, C.L., Sharma, V., Charney, D.S., Herbert, R., et al. (2008). Enduring mental health morbidity and social function impairment in world trade center rescue, recovery, and cleanup workers: the psychological dimension of an environmental health disaster. Environmental health perspectives, 116(9), 1248.

- Suflita, J.M., Gerba, C.P., Ham, R.K., Palmisano, A.C., Rathje, W.L., & Robinson, J.A. (1992). The world's largest landfill. Environmental science & technology, 26(8), 1486-1495.

- Sutker, P.B., Uddo, M., Brailey, K., Allain, A.N., & Errera, P. (1994). Psychological symptoms and psychiatric diagnoses in Operation Desert Storm troops serving graves registration duty. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 7(2), 159-171.

- Taylor, A., & Frazer, A. (1982). The stress of post-disaster body handling and victim identification work. Journal of Human Stress, 8(4), 4-12.

- Ursano, R.J., & Hermsen, J.M. (1996). Posttraumatic stress symptoms following forensic dental identification: Mt. Carmel, Waco, Texas. American Journal of Psychiatry, 1(53), 779.

- Ursano, R.J., & McCarroll, J.E. (1990). The nature of a traumatic stressor: Handling dead bodies. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 178(6), 396-398.

- Ursano, R.J., Fullerton, C.S., Kao, T.C., & Bhartiya, V.R. (1995). Longitudinal assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression after exposure to traumatic death. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 183(1), 36-42.

- Ventureyra, V., AG, E.R., Yao, S.N., Cottraux, J., Note, I., & Mey-Guillard, D. (2001). The validation of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist Scale in posttraumatic stress disorder and nonclinical subjects. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics, 71(1), 47-53.

- Vlahov, D., Galea, S., Resnick, H., Ahern, J., Boscarino, J.A., Bucuvalas, M., et al. (2002). Increased Use of Cigarettes, Alcohol, and Marijuana among Manhattan, New York, Residents after the September 11th Terrorist Attacks. American Journal of Epidemiology, 155(11), 988-996.

- Weathers, F.W., Litz, B.T., & Herman, D.S., (1993). The PTSD Checklist (PCL): reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, TX.

- WTC Operational Statistics. (2015). Retrieved September 3, 2015, from http://www.nyc.gov/html/ocme/downloads/pdf/public_affairs_ocme_pr_WTC_Operational_Statistics.pdf

Relevant Topics

- Cementogenesis

- Coronal Fractures

- Dental Debonding

- Dental Fear

- Dental Implant

- Dental Malocclusion

- Dental Pulp Capping

- Dental Radiography

- Dental Science

- Dental Surgery

- Dental Trauma

- Dentistry

- Emergency Dental Care

- Forensic Dentistry

- Laser Dentistry

- Leukoplakia

- Occlusion

- Oral Cancer

- Oral Precancer

- Osseointegration

- Pulpotomy

- Tooth Replantation

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 14260

- [From(publication date):

April-2015 - Apr 04, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 9620

- PDF downloads : 4640