Clinical and Biochemical Predictors of Mortality of COVID-19 Cases from Pakistan

Received: 10-May-2022 / Manuscript No. JIDT-22-63466 / Editor assigned: 12-May-2022 / PreQC No. JIDT-22-63466 (PQ) / Reviewed: 26-May-2022 / QC No. JIDT-22-63466 / Revised: 02-Jun-2022 / Manuscript No. JIDT-22-63466 (R) / Published Date: 13-May-2022 DOI: 10.4172/2332-0877.1000502

Abstract

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious respiratory disease with several biochemical alterations reflecting the main pathophysiological characteristics associated with the disease severity and mortality. We have reported clinical and biochemical predictors of mortality among 200 patients: 57 survivors and 143 non-survivors. Data on patient’s demographic characteristics, radiological findings, laboratory findings and comorbidities was collected. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages (frequencies) while continuous variables were reported as mean ± SD (Standard Deviation). Mann-Whitney t-test, One-way ANOVA, Pearson’s correlation and ROC curves were used for statistical analysis with a p-value of 0.05. Out of 200 patients, 64% were male, and 36% were female. The median age for deceased and recovered cases was 61 (IQR: 24,70) and 36 (IQR: 26,52) years, respectively. Among co-morbid conditions hypertension (p-value 0.079) and cardiac vascular disease (p-value 0.064) was significantly higher in deceased cases. Lymphopenia, GGO, fever, cough are the hallmarks of disease were observed frequently. Increased level of inflammatory biomarkers including CRP (p-value<0.0001), ESR (p-value<0.0001), Ferritin (p-value 0.001), LDH (p-value<0.0001) and PCT (p-value 0.022), coagulation factors such as D-Dimers (p-value 0.0003), Fibrinogen (p-value<0.0001), increased prothrombin time and decreased activated partial thromboplastin time were associated with disease severity. Among serum electrolytes decreased levels of potassium (p-value 0.0004), sodium (p-value<0.0001), chloride (p-value 0.0011) and calcium (p-value 0.0021) but increased level of magnesium (p-value 0.0002) were observed in non-surviving COVID-19 patients. Among hepatocytic biomarkers increased levels of ALT (p-value 0.0001), AST (p-value 0.0011), albumin (p-value 0.0044), alkaline phosphatase (p-value 0.0260) and bilirubin (p-value<0.0001) were observed in non-survivors. The SARS-CoV-2 infection is characterized by several biochemical alterations, which can be recognized by specific biomarkers. Among all biomarkers associated with disease severity and mortality lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, CRP, ESR, PCT, LDH, AST, ALT, D-dimer, CK, albumin, creatinine phosphatase represents the most predictive parameters of severe COVID-19 infection.

Keywords: COVID-19; Co-morbidities; Biochemical parameters; Hematological profiling; Inflammatory markers

Introduction

COVID-19 is an infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The outbreak started from Wuhan China in 2019 and was globally spread [1]. The virus can spread in the form of small droplets through coughing, sneezing, speaking, or breathing from infected individuals. These droplets range from smaller aerosols to larger respiratory droplets and are of >5-10 um in size. People can be infected by breathing in the virus if you are in close contact (within 1 meter) of COVID-19 infected individual, or by touching a contaminated surface and then rubbing the eyes, nose or mouth with hands without sanitization. The virus spreads more easily indoors and in crowded settings [2,3].

The transmission and severity of infection is increasing much rapidly with the emergence of new variants [4]. People infected with COVID-19 experience a wide range of symptoms that range from mild to moderate symptoms and may recover without special treatment. However, some people may not experience any symptoms at all and will remain asymptomatic while some become seriously ill and require urgent medical attention or hospitalization [5]. Symptoms including cough, fever, chills, Shortness of Breath (SOB), fatigue, loss of smell and taste, sore throat, chest congestion, vomiting, nausea, diarrhea, muscle ache etc. Typically, the symptoms may appear after 2-14 days of exposure and can vary from mild to severe symptoms [6]. Many severe or critically ill patients had been hospitalized requiring the intensive [7].The clinical course of COVID-19 ranges from asymptomatic to mild and moderate infection which can lead to critical stages and even death [8].

Diagnosis of the infection is performed usually using PCR reaction which detects viral nucleic acids in the specimens [9]. Despite the supportive help, patients of COVID-19 can face serious respiratory deterioration and ultimately death [10]. Identification of the patients who need supportive help and care can aid in saving the life of the individual. For this, certain signatures need to be identified [11]. Alterations in these signatures can lead a person to its mortality. These biomarkers can aid in confirmation and classification of disease severity, early diagnosis, rationalizing therapies and predicting disease outcomes [12]. Previous studies have demonstrated that there have been high levels of neutrophils, lymphopenia, and C-reactive protein in critical patients of COVID-19 [13,14]. Besides these changes, increase in levels of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and interleukin 6, decreased levels of CD4+ and CD8+ are important marks as both of them are involved in determining disease severity and clinical outcomes [15]. In addition to these inflammation-linked indicators, disease severity can also be linked with co-morbidities. COVID-19 patients could develop a life-threatening situation if they have the co-morbid conditions such as diabetes, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), Cardiovascular Diseases (CVD), hypertension, malignancies, HIV etc. [16,17]. Multiple studies have been conducted to observe various biochemical and hematological parameters from blood samples of COVID infected patients during hospitalization. Gradual decrease of lymphocyte count, thrombocytopenia, elevated CRP, procalcitonin, increased liver enzymes, decreased renal function, and coagulation derangements, were more common in critically ill patient groups and associated with a high incidence of clinical complications [18,19].

In this study, we have performed a comprehensive evaluation of clinical characteristics and biochemical parameter of 200 patients with COVID-19 admitted to Jinnah hospital, Lahore, Pakistan.

Materials and Methods

Study design and patient characterization

This was a retrospective single-center study of 200 patients diagnosed with severe COVID-19 infection admitted in Pulmonology ward of Jinnah hospital, Lahore from March to June 2020. All patients were diagnosed as per interim guidelines of National Institute of Health (NIH) and World Health Organization (WHO). Patients were categorized as “severe” based on the guidelines defined by NIH; a) shortness of breath with >30 times/min Respiratory Rate (RR). b) <93% oxygen saturation at rest, c) Arterial partial oxygen pressure (PaO2) of <300 mm Hg, d) progression of lesions with >50% in 24-48 hour on Chest X-ray (CXR) or High-Resolution Chest Scan (HRCT), requirement of mechanical ventilation [20].

Data collection

The medical record files of all the admitted patients were reviewed by a team of researchers and physicians. The medical record of each patient was taken from both paper and electronic records using the Medical Record Number (MRN). Extracted data included patients’ demographics, clinical and laboratory findings, co-morbidities, treatment outcome was collected by using standardized data collection form.

Demographic data

Demographic data included age and gender of patients. Clinical data included the history and duration of various signs and symptoms of COVID-19 infection such as fever, sore throat, cough, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, loss of smell, loss of taste, headache, shortness of breath, oxygen saturation level etc. A certified consultant radiologist performed the radiological interpretations, blinded from the clinical presentation of the patients, and made a subjective estimation of severity of the disease from CXR/HRCT or both.

Routine laboratory tests

COVID-19 patients were diagnosed with the WHO recommended Real Time Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) assay. Nasopharyngeal/oropharyngeal swabs or both were taken from all the patients at the time of admission and at multiple time points after the admission. Qualitative detection of SARS-CoV-2 was detected as per NIH’s guidelines [21]. Routine laboratory tests that were performed on all patients included various hematological, blood gas and biochemical parameters along with coagulation, inflammatory, liver impairment and kidney lymphocyte count, dysfunction markers. Hematological parameters included White Blood Cell Count (WBC), Neutrophil count, Neutrophil to Lymphocyte ratio and platelets count. Blood gas parameters included Hemoglobin (HB), PO2, PCO2, pH, bicarbonates (HCO3) and Sulphates (SO2). Among inflammatory vitals, CRP (C-Reactive Protein), ESR (Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate), Ferritin, LDH (Lactate Dehydrogenase) and Pro-Calcitonin were tested. Among co-agulation factors, PT (Prothrombin time), aPTT (activated partial thromboplastin time) and Fibrinogen. Among muscle markers, Creatinine Kinase, Total protein, Glucose and Troponin were measured. Serum electrolytes under observation included Potassium (K+), Sodium (Na+), Chloride (Cl-), Calcium (Ca2+) and Magnesium (Mg2+). To observe the effect of COVID-19 infection on liver impairment, ALT (Alanine Amino Transferase), AST (Aspartate Aminotransferase), Albumin, Total bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase were the markers analyzed. For kidney dysfunction, creatinine, BUN (Blood Urea Nitrogen) and uric acid were tested in blood samples.

Co-morbid conditions and clinical outcome

Among severely ill and hospitalized COVID-19 patients, the comorbidities like hypertension, diabetes (type 2), cardiovascular disease, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), asthma, renal disorders etc. were considered into account. Clinical outcome of patients under analyses was Pneumonia (CAP), ARDS (Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome) and acute cardiac injury. The final output or reason of death for deceased cases was also noted down as declared on their death documents.

Statistical analysis

To describe patient’s demographic characteristics, radiological findings, laboratory findings and comorbidities, the descriptive statistics was used. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages (frequencies) while continuous variables were reported as mean ± SD (Standard Deviation). Chi-square was used to compare of categorical variables with a p-value 0.05 of significance. Mann-Whitney t-test and One-way ANOVA was used for the comparison of the mean value for continuous variables. Pearson correlation coefficient was used to correlate biomarkers and continuous clinical variables. ROC (receiver operator curves) was used to calculate the predictive values of by identifying Youden's index. p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. To identify predictors of clinical characteristics associated with mortality, logistic regression analysis was used, and Odds Ratio (OR) were calculated with 95% Confidence Interval (CI) with a p-value<0.05 SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) version 25.0 software (SPSS Inc.) and GraphPad Prism (Version 8, San Diego, CA) were used to perform all statistical analysis.

Results

Demographic characteristics of patients

Demographic and clinical characteristic of COVID-19 patients (n=200) with their final outcomes are summarized in Table 1. Out of 200, 143 (72%) patients were declared dead due to COVID infection and 57 (28%) were discharged once they recovered from infection and were physically stable. In total, 128 patients (64%) were male, and 72 patients (36%) were female. The median age of all patients was 54 years (IQR: 29-65 years). The median age for deceased and recovered cases was 61 (IQR: 24,70) and 36 (IQR: 26,52) years respectively. When stratified with age group, 26% patients (n=53) were of >24-40 years, 29% patients (n=57) were of 40-65 years and 45% patients (n=90) were of >65 years of age. Among deceased cases, maximum deaths (50%) were reported among older peoples of ore that >65 years of age while in recovered cases, maximum no. of deaths (44%) reported were of young age i.e. 24-40 years. Clinical outcome of the patients showed that 55% cases (n=110) had Pneumonia, 35% (n=70) had ARDS and 10% (n=20) had acute-heart injury. The data for co-morbid conditions showed that 35% of patients (n=70) had hypertension, 28% (n-55) had diabetes, 15% (n=30) had cardiac vascular disease. Hypertension and cardiac vascular disease was significantly higher in deceased cases as compared to survived case with a p-value 0.079 and 0.064 respectively. A significant difference for duration of fever was observed between deceased (mean 9.2 days) and recovered cases (mean 6.1 days) with a p-value of 0.02. Deceased cases has a significant longer duration of hospitalization (mean 28 days) as compared to survived cases (mean, 5 days) with a p-value of 0.0019 (Table 1).

| Variables | Total cases N (%) | Survivors N (%) | Non-survivors N (%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Patients | 200 (100) | 57 (28) | 143 (72) | 0.04 | |

| Age (median, Y) | 47 | 38 | 62 | 0.0001 | |

| >24-40 Y | 42 (21) | 14 (24) | 28 (20) | 0.005 | |

| >40-65 Y | 68 (34) | 23 (40) | 43 (30) | 0.0003 | |

| > 65 Y | 90 (45) | 20 (35) | 72 (50) | 0.105 | |

Gender |

|||||

| Male | 128 (64) | 25 (20) | 103 (80) | 0.201 | |

| Female | 72 (36) | 18 (44) | 54 (56) | 0.091 | |

Clinical outcome |

|||||

| Pneumonia | 110 (55) | 37 (42) | 73 (58) | 0.004 | |

| ARDS | 70 (35) | 8 (11) | 62 (89) | 0.398 | |

| Acute Heart Injury | 20 (10) | 2 (2) | 18 (98) | 0.422 | |

Co-morbidity |

|||||

| Hypertension | 70 (35) | 18 (40) | 52 (60) | 0.079 | |

| Diabetes | 55 (28) | 11 (33) | 44 (67) | 0.191 | |

| Chronic Lung disease | 45 (22) | 3 (6) | 42 (94) | 0.497 | |

| Cardiac Vascular disease | 30 (15) | 8 (26) | 22 (74) | 0.064 | |

| Duration of Fever, days | 7.9 + 4.8 | 6.1 + 4.4 | 9.2 + 4.7 | 0.021 | |

| Hospital admission, days | 20 (9, 28) | 15 (9, 20) | 28 (18, 31) | 0.0019 | |

| Noninvasive mechanical ventilation | 65 (56) | 7 (11) | 58 (89) | 0.405 | |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 98 (49) | 3 (3) | 95 (97) | 0.573 | |

Clinical characteristics |

|||||

| Fever | 190 | 50 (88) | 140 (98) | 0.069 | |

| Cough | 154 | 45 (79) | 109 (76) | 0.032 | |

| Expectoration | 134 | 38 (67) | 96 (67) | 0.041 | |

| Dyspnea | 146 | 21 (37) | 125 (87) | 0.32 | |

| Headache | 170 | 37 (65) | 133 (93) | 0.153 | |

| Weakness | 190 | 49 (86) | 141 (99) | 0.077 | |

| Diarrhea | 158 | 40 (70) | 118 (83) | 0.085 | |

| Chills | 185 | 46 (81) | 139 (97) | 0.037 | |

| Shortness of Breadth | 182 | 53 (93) | 137 (96) | 0.047 | |

| Alternate taste/smell | 158 | 39 (68) | 119 (83) | 0.096 | |

Radiological characteristics |

|||||

| GGO | 200 | 57 (100) | 143 (100) | 0.04 | |

| Consolidation | 136 | 41 (72) | 95 (66) | 0.023 | |

| Infiltration | 139 | 37 (65) | 102 (71) | 0.065 | |

| GGO + Consolidation | 189 | 45 (79) | 108 (76) | 0.03 | |

| Pl. Effusion | 120 | 23 (40) | 67 (47) | 0.081 | |

Table 1: Demographic and Clinical outcome of COVID-19 patients.

Clinical and radiological characteristics of patients

Descriptive statistics and Mann Whitney t-test for clinical symptoms showed that fever (p-value 0.069), cough (p-value 0.032), expectoration (p-value 0.041), weakness (p-value 0.077), diarrhea (p-value 0.085), chills (p-value 0.037), shortness of breath (p-value 0.047), loss of smell and taste (p-value 0.096) were significantly experienced in higher proportion by deceased cases as compared to recovered cases. Radiological features based on High Resolution Chest Scan (HRCT) showed that Ground Glass Opacity (GGO) (p-value 0.040), consolidation (p-value 0.023), infiltration (p-value 0.065), GGO and consolidation in combination (p-value 0.030) and pleural effusion (p value 0.081) were significantly prevalent in deceased cases as compared to recovered cases (Table 1).

Hematological profiling of COVID-19 patients

Different hematological parameters were compared between recovered and deceased group to identify the potential parameter involved in disease severity and ultimate death. All the tests were performed within 48 hours of hospital admission. No significant difference was observed in WBCs count and platelet count among both groups. However, the lymphocyte count and lymphocyte ratio showed a significant difference. The mean lymphocyte count (mean; 0.81, SD 1.06) and lymphocyte ratio (mean; 16%, SD ± 13.1) of deceased cases was significantly lower than the mean lymphocyte count (mean 1.5, SD ± 1.2) and lymphocyte ratio (mean; 24%, SD ± 18.4) of recovered cases with a p-value 0.0003 and 0.005, respectively. The mean value of Hb in deceased group was 10.74 which is significantly lower than that of recovered cases (mean; 13.39) with a p-value of <0.0001. Among blood gas levels, PO2 and PCO2 were significantly lower in deceased cases with a p-value of 0.023 and 0.032 respectively (Table 2).

| Characteristics | Normal range | Total cases N=200 | Survivors N=57 | Non-survivors N=143 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematological parameters (Mean + SD) | |||||

| WBCs *109/L | 04-10 | 4.9 ± 3.6 | 4.5 ± 3.3 | 5.4 ± 4.2 | 0.217 |

| Lymphocyte Count *109/L | 0.8-4 | 1.6 ± 1.39 | 1.5 ± 1.2 | 0.81 ± 1.06 | 0.0003 |

| Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio % | 20-40% | 25 % ±12.8 | 24% ± 18.4 | 16% ± 13.1 | 0.005 |

| Platelets *109/L | 100-300 | 195.3 ± 60.5 | 187.8 ± 92.3 | 206.1 ± 81.9 | 0.381 |

| Blood gas (Mean + SD) | |||||

| Hemoglobin g/dL | 11-16 | 12.49 ± 1.80 | 13.39 ± 1.65 | 10.74 ± 2.68 | <0.0001 |

| PO2 (mmHg) | 80- 100 | 76.91 ± 42.9 | 86.70 ± 54.9 | 68.37 ± 38.0 | 0.023 |

| PCO2 (mmHg) | 35-405 | 38.8 ± 18.5 | 41.53 ± 19.5 | 35.38 ± 14.09 | 0.032 |

| pH | 7.35-7.45 | 7.43 ± 1.2 | 7.46 ± 0.44 | 7.39 ± 1.29 | 0.568 |

| HCO3 (mmol/L) | 22-28 | 26.62 ± 10.5 | 27.8 ± 9.52 | 24.0 ± 9.75 | 0.012 |

| SO2 (mmHg) | 75-100 | 87.7 ± 41.1 | 82.4 ± 40.2 | 80.84 ± 43.0 | 0.803 |

| Inflammatory markers (Mean + SD) | |||||

| CRP mg/L | < 10 | 62 ± 85.5 | 15.6 ± 21.04 | 76.59 ± 90.06 | <0.0001 |

| ESR mm/h | 0-15 | 29.8 ± 13.9 | 23.4 ± 12.3 | 43.6 ± 15.5 | <0.0001 |

| Ferritin mg/L | 10-322 | 205 ± 1762 | 86 ± 244 | 300 ± 2058 | 0.001 |

| LDH U/L | 109-245 | 272 ± 174 | 214 ± 68 | 303 ± 205 | <0.0001 |

| Pro-Calcitonin ng/ml | < 0.5 | 0.22 ± 0.64 | 0.06 ± 0.26 | 0.28 ± 0.71 | 0.0223 |

| Coagulation factors (Mean + SD) | |||||

| PT seconds | 60-70 | 65 ± 2.4 | 64.91 ± 7.50 | 69.06 ± 8.45 | <0.0001 |

| aPTT seconds | 30-40 | 36 ± 1.8 | 35.47 ± 5.89 | 34.06 ± 15.48 | 0.005 |

| D-Dimers ng/ml | <250 | 1028 ± 1519 | 534.3 ± 531.6 | 1226 ± 1698 | 0.0003 |

| Fibrinogen mg/dL | 200-400 | 595.5 ± 225 | 478.7 ± 156.7 | 713.9 ± 292.5 | <0.0001 |

| Muscle markers (Mean + SD) | |||||

| Creatinine Kinase U/L | 30-170 | 195 ± 366.5 | 123.8 ± 147.9 | 272.2 ± 578.9 | 0.0488 |

| Total protein g/L | 60-83 | 71.54 ± 6.85 | 68.75 ± 7.30 | 74.47 ± 8.44 | <0.0001 |

| Glucose mg/dL | <140 | 88 ± 8.54 | 76.75 ± 8.31 | 108.6 ± 11.77 | <0.0001 |

| Troponin ng/ml | 0-0.15 | 0.03 ± 0.24 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.59 | <0.0001 |

| Serum electrolytes (Mean + SD) | |||||

| Potassium mmol/L | 3.40-4.50 | 3.98 ± 0.63 | 3.70 ± 0.58 | 3.45 ± 0.52 | 0.0004 |

| Sodium mmol/L | 136-145 | 138 ± 3.2 | 137.8 ± 1.88 | 133 ± 4.42 | <0.0001 |

| Chloride mmol/L | 95-105 | 98 ± 7.82 | 101.7 ± 8.68 | 98.5 ± 9.08 | 0.0011 |

| Calcium mg/L | 8.5-10.2 | 8.21 ± 5.41 | 9.51 ± 4.48 | 7.99 ± 2.72 | 0.0021 |

| Magnesium mg/dL | 1.7-2.2 | 2.0 ± 0.94 | 1.91 ± 0.20 | 2.11 ± 0.34 | 0.0002 |

| Hepatic markers | |||||

| ALT U/L | 7-40 | 39.2 ± 80.9 | 21.9 ± 15.6 | 45.54 ± 93.75 | 0.0001 |

| AST U/L | 13-40 | 43 ± 74.8 | 23.2 ± 8.9 | 50.19 ± 86.33 | 0.0011 |

| Albumin g/L | 35-50 | 39.3 ± 5.2 | 25.52 ± 7.21 | 29.29 ± 7.53 | 0.0044 |

| Total bilirubin umol/L | 3.4-17.1 | 11.5 ± 4.6 | 10.90 ± 1.88 | 14.66 ± 2.81 | <0.0001 |

| Alkaline Phosphatase IU/L | 440-147 | 91 ± 41.58 | 90.33 ± 35.96 | 87.73 ± 81.02 | 0.026 |

| Renal markers | |||||

| Creatinine mg/L | 05-08 | 10.3 ± 8.2 | 8.30 ± 4.28 | 10.76 ± 8.79 | 0.0001 |

| BUN nmol/L | 2-7 | 3.8 ± 2.3 | 3.92 ± 0.78 | 5.66 ± 2.81 | 0.0005 |

| Uric acid mg/dL | 2.7-8.5 | 3.9 ± 0.72 | 4.68 ± 0.82 | 3.31 ± 0.76 | <0.0001 |

Table 2: Characteristics of Biochemical parameters of COVID-19 patients.

Characteristics of biochemical parameters

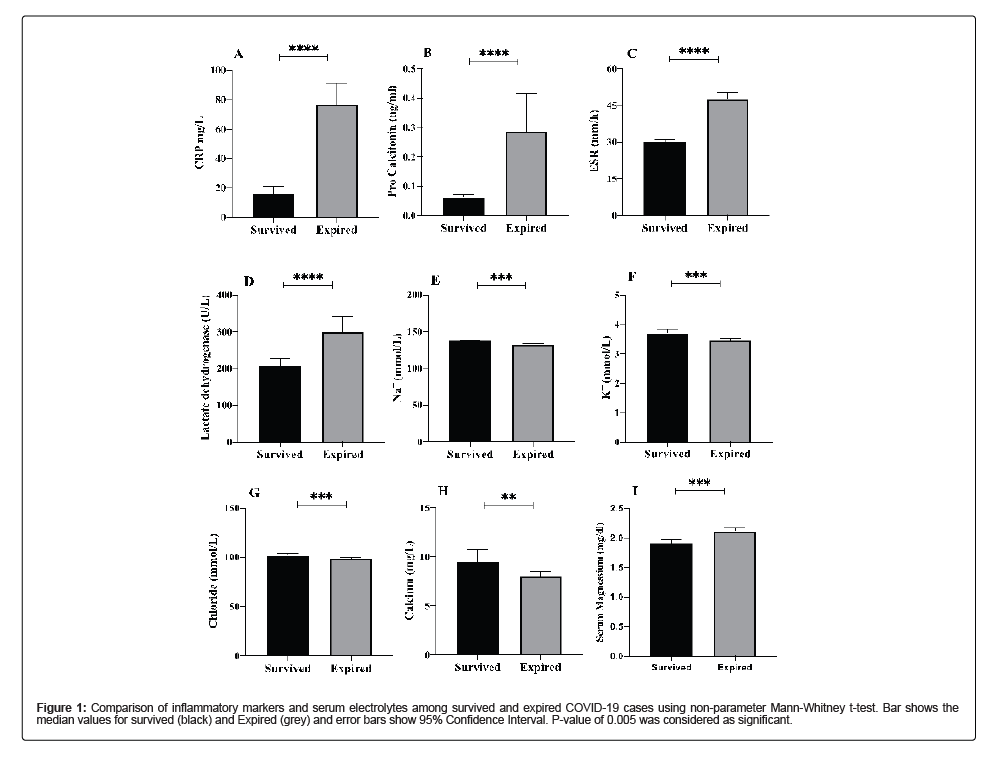

Different inflammatory markers that play a vital role in infection were analyzed that included CRP, ESR, Ferritin, LDH and Pro- Calcitonin. As, compared to recovered cases, the levels of all the inflammatory markers monitored were elevated in deceases cases. CRP level were elevated 7 folds (p-value<0.00001), ferritin levels were elevated 3.4 folds (p-value 0.001), LDH levels were increased by 1.4 folds (p-value<0.00001) and pro-calcitonin levels were increased by 5.6 folds (p-value 0.0223) in deceased patients. To observe the serum electrolyte imbalance, Potassium (K+), Sodium (Na+), Chloride (Cl-), Calcium (Ca+2) levels were checked. Potassium levels were significantly lower in deceased patients (mean; 3.45, SD 0.52) as compared to recovered cases (mean; 3.70, SD ± 0.58) with a p-value of 0.0004. Sodium levels were significantly low in deceased cases (mean; 133, SD ± 4.42) as compared to recovered cases (mean; 137 ± 1.87) with a p-value of <0.00001). Similarly, low levels of Chloride and Calcium were observed in deceased patients as compared to recovered cases with a p-value of 0.0011 and 0.0021, respectively (Table 2 and Figure 1).

Figure 1: Comparison of inflammatory markers and serum electrolytes among survived and expired COVID-19 cases using non-parameter Mann-Whitney t-test. Bar shows the median values for survived (black) and Expired (grey) and error bars show 95% Confidence Interval. P-value of 0.005 was considered as significant.

Characteristics of coagulation and muscle markers

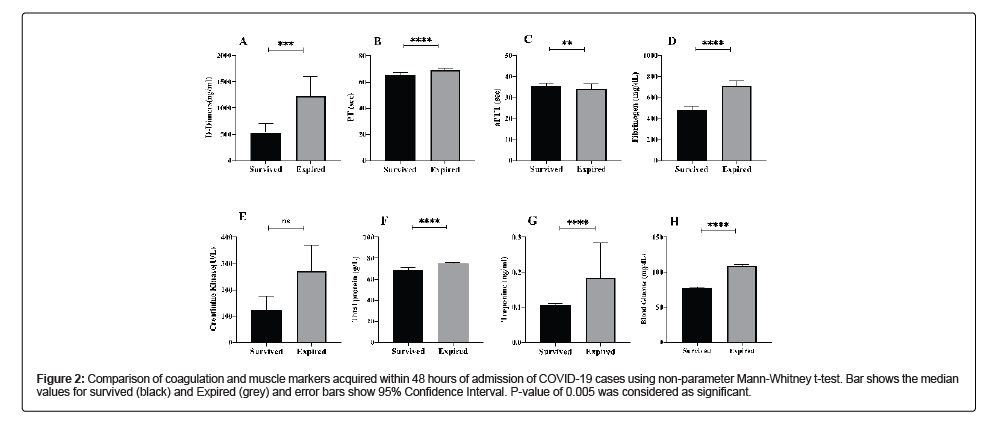

Among coagulation factors, four factors were observed, PT, aPTT, D-Dimers and Fibrinogen. The delay in the coagulation for PT was increased 1.06 folds (p-value<0.0001) and that of aPTT was increased by 1.18 folds (p-value 0.0050) in deceased cases. D-Dimers were increased 2.3 folds high in deceased cases (p-value<0.0003) whereas Fibrinogen was 1.5 folds high in deceased cases (p-value<0.0001) in comparison to the recovered cases. Among muscle markers, creatinine kinase was 2.21 folds high (p-value 0.048), total proteins were 1 fold high (p-value<0.0001), Troponin was 1.8 folds high (p-value<0.0001) and blood glucose was 1.4 folds high (p-value<0.0001) in deceased cases as compared to record cases (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Figure 2: Comparison of coagulation and muscle markers acquired within 48 hours of admission of COVID-19 cases using non-parameter Mann-Whitney t-test. Bar shows the median values for survived (black) and Expired (grey) and error bars show 95% Confidence Interval. P-value of 0.005 was considered as significant.

Markers for liver impairment and renal dysfunction

To administer the effect of COVID infection on liver impairment, the alteration of hepatocytes damage biomarkers, such as Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT), Aspartate Aminotransferase (AST), albumin, bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase were observed. The data showed that both alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase were significantly increased in deceased cases (mean ALT; 45.54, mean AST; 50.19) as compared to recovered cases (mean ALT; 21.9, mean AST; 23.2) with a p-value of 0.001 and 0.0011 respectively. The amount of albumin in deceased patients was significantly lower (mean; 29.29, SD ± 7.53) as compared to recovered cases (mean; 25.52, SD ± 7.21) with a p-value of 0.0044. The amount of total bilirubin was significantly increased in deceased cases (mean; 14.66, SD ± 2.81) as compared to recovered cases (mean; 10.90, SD ± 1.88) with a p-value of <0.0001. On the other hand, alkaline phosphatase was observed to be in low concentration in deceased patients (mean; 87.73, SD + 81.02) as compared to recovered cases (mean; 90.33, SD ± 35.96) with a p-value of 0.026. For renal dysfunction, creatinine, BUN and uric acid were observed. The data showed that amount creatinine was 1.3 folds high (p-value 0.0001) and BUN was 1.5 folds high (0.0005) in deceased cases as compared to recovered cases. However, uric acid was 1.4 folds low in deceased cases as compared to recovered cases (Table 2 and Figure 3).

Pearson’s correlation coefficient showed a strong correlation for gender (r= 0.85) while moderate correlation was found for serum sodium (r=0.545), Ferritin (r=0.445), D-dimers (r=0.469), LDH (r=0.584), pro-calcitonin (r=0.435), bilirubin (r=0.434) and comorbidities (r=0.461) with a p-value of <0.001. A negative correlation of moderate level was found for albumin (r=-0.599) with a p-value of >0.0001 (Table 3).

| Parameters | R* | p-value | Parameters | R* | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.856 | <0.0001 | LDH | 0.584 | <0.0001 |

| Gender | 0.129 | <0.0001 | Pro-calcitonin | 0.435 | <0.0001 |

| WBCs | 0.241 | 0.0005 | Fibrinogen | 0.212 | <0.0001 |

| Platelets | 0.23 | 0.0001 | Pt | 0.263 | <0.0001 |

| Lymphocyte Count | -0.285 | 0.0004 | aPTT | 0.29 | 0.0003 |

| ESR | 0.212 | 0.002 | ALT | 0.246 | 0.0004 |

| Serum Na | 0.545 | <0.001 | AST | 0.324 | <0.0001 |

| Serum K | -0.249 | 0.003 | Albumin | -0.599 | <0.0001 |

| Serum Ca | 0.215 | 0.002 | Bilirubin | 0.43 | <0.0001 |

| Serum Chloride | 0.27 | 0.001 | Creatinine | 0.261 | <0.0001 |

| Serum Magnesium | 0.31 | <0.0001 | Urea | 0.248 | 0.0003 |

| CRP | 0.347 | <0.0001 | BUN | 0.312 | 0.002 |

| Ferritin | 0.445 | <0.0001 | Co-morbidities | 0.461 | <0.0001 |

| D-Dimers | 0.469 | <0.0001 | Plasma Glucose | 0.363 | <0.0001 |

Note: *Pearson’s correlation coefficient

Table 3: Correlation of demographic factor and disease parameters with COVID-19 infection.

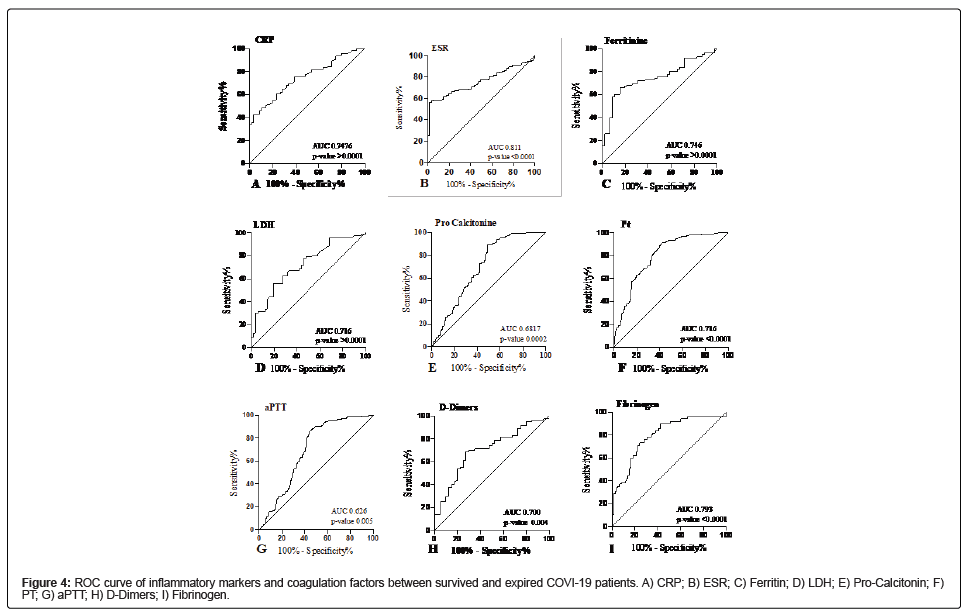

Association of inflammatory markers and coagulation factors with disease severity and mortality in COVID-19 patients

ROC analysis inflammatory markers and coagulation factors showed a significant association with disease severity and mortality between survived and expired patients infected with COVID-19 infection (Table 4). All the variables were dichotomized, and logistic regression showed a significant association under ROC defined cutoff among survived and expired patients. The ROC curve for CRP (AUC=0.746, CI 0.768-0.815, p-value <0.0001) suggested the best cut off point was 10.17 mg/L with a sensitivity of 75.71% and specificity of 66.07% (Figure 4A). The ROC curve for ESR (AUC=0.811, CI 0.747- 0.875, p-value<0.0001) suggested the best cut-off point was 38 mm/h with a sensitivity of 81.12% and specificity of 100% (Figure 4B). The ROC curve for ferritin (AUC=0.746, CI 0.662-0.831, p-value<0.0001) suggested the best cut off point was 127.3 g/L with a sensitivity of 72.94% and specificity of 60.87% (Figure 4C). The ROC curve for LDH (AUC=0.716, CI 0.628-0.804, p-value<0.0001) suggested the best cut off point was 215 U/L with a sensitivity of 70.93% and specificity of 66% (Figure 4D). The ROC curve for pro-calcitonin (AUC=0.687, CI 0.675- 0.725, p-value 0.0002) suggested the best cut off point was 0.45 ng/ml with a sensitivity of 72.79% and specificity of 65.45% (Figure 4E). The ROC curve for coagulation factors such as PT indicated the best cut-off point was 67.5 seconds (AUC= 0.716, CI 0.641-0.792, p-value<0.0001) with a sensitivity and specificity of 68.53% and 64.91% respectively (Figure 4F). The ROC curve for aPTT indicated the best cut-off point was 36.5 seconds (AUC=0.626, CI 0.549-0.703, p-value 0.005) with a sensitivity and specificity of 66.43% and 64.91% respectively (Figure 4G). The ROC curve for D-Dimers indicated the best cut-off point was 463.5 ng/ml (AUC=0.702, CI 0.603-0.797, p-value 0.0004) with a sensitivity and specificity of 70% and 70%, respectively (Figure 4H). The ROC curve for fibrinogen indicated the best cut-off point was 515 mg/dL (AUC=0.793, CI 0.723-0.863, p-value<0.0001) with a sensitivity and specificity of 66.43% and 64.91%, respectively (Figure 4I).

| Characteristics | AUC | 95% Confidence interval | Cut-off | Sensitivity | Specificity | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||||

| Inflammatory markers | |||||||

| CRP mg/L | 0.746 | 0.678 | 0.8155 | 10.17 | 75.71 | 66.07 | <0.0001 |

| ESR mm/h | 0.811 | 0.747 | 0.8753 | 38 | 81.12 | 100 | <0.0001 |

| Ferritin mg/L | 0.746 | 0.662 | 0.8311 | 127.3 | 72.94 | 60.87 | <0.0001 |

| LDH U/L | 0.716 | 0.628 | 0.8045 | 215 | 70.93 | 66 | <0.0001 |

| Pro-calcitonin ng/ml | 0.687 | 0.6756 | 0.725 | ? | 72.79 | 65.45 | 0.0002 |

| Coagulation factors | |||||||

| PT seconds | 0.716 | 0.6417 | 0.792 | 67.5 | 68.53 | 64.91 | <0.0001 |

| aPTT seconds | 0.626 | 0.5498 | 0.703 | 36.5 | 66.43 | 64.91 | 0.0053 |

| D-Dimers ng/ml | 0.7 | 0.6033 | 0.7977 | 463.5 | 70 | 70 | 0.0004 |

| Fibrinogen mg/dL | 0.793 | 0.723 | 0.8639 | 515 | 78.17 | 66.67 | <0.0001 |

| Muscle markers | |||||||

| Creatinine Kinase | 0.513 | 0.417 | 0.6105 | 145 | 56.01 | 52.11 | 0.8067 |

| Total protein | 0.707 | 0.6175 | 0.7969 | 68.5 | 78.4 | 68.23 | <0.0001 |

| Glucose | 1 | 1 | 1 | 126 | 100 | 100 | <0.0001 |

| Troponin | 0.89 | 0.8382 | 0.9428 | 0.05 | 89.05 | 100 | <0.0001 |

| Serum electrolytes | |||||||

| Potassium mmol/L | 0.658 | 0.5683 | 0.7478 | 3.7 | 75.18 | 71.43 | 0.0005 |

| Sodium mmol/L | 0.812 | 0.7529 | 0.8721 | 136.5 | 76.06 | 89.47 | <0.0001 |

| Chloride mmol/L | 0.651 | 0.5723 | 0.7315 | 101.5 | 60.56 | 56.14 | 0.0012 |

| Calcium mg/L | 0.639 | 0.5611 | 0.7181 | 8.7 | 60.71 | 62.4 | 0.0021 |

| Hepatic markers | |||||||

| ALT U/L | 0.696 | 0.6035 | 0.7894 | 19.5 | 72.41 | 64.29 | 0.0002 |

| AST U/L | 0.67 | 0.5829 | 0.7577 | 20.56 | 72.17 | 65.85 | 0.0012 |

| Albumin g/L | 0.651 | 0.5522 | 0.7515 | 27.1 | 65.77 | 63.89 | 0.0047 |

| Bilirubin umol/L | 0.874 | 0.8174 | 0.9306 | 11.8 | 99.3 | 70.69 | <0.0001 |

| Alkaline Phosphatase IU/L | 0.608 | 0.5086 | 0.7086 | 80.5 | 70.3 | 64.44 | 0.026 |

| Renal markers | |||||||

| Creatinine mg/L | 0.674 | 0.5915 | 0.7581 | 7.9 | 72.79 | 65.45 | 0.0002 |

| BUN nmol/L | 0.652 | 0.5787 | 0.7265 | 3.92 | 73.43 | 72.41 | 0.0007 |

| Uric acid mg/dL | 0.891 | 0.849 | 0.9338 | 7.8 | 78.91 | 72.45 | <0.0001 |

Table 4: Bivariate analysis of biochemical parameters associated with disease severity and mortality in COVID-19 patients.

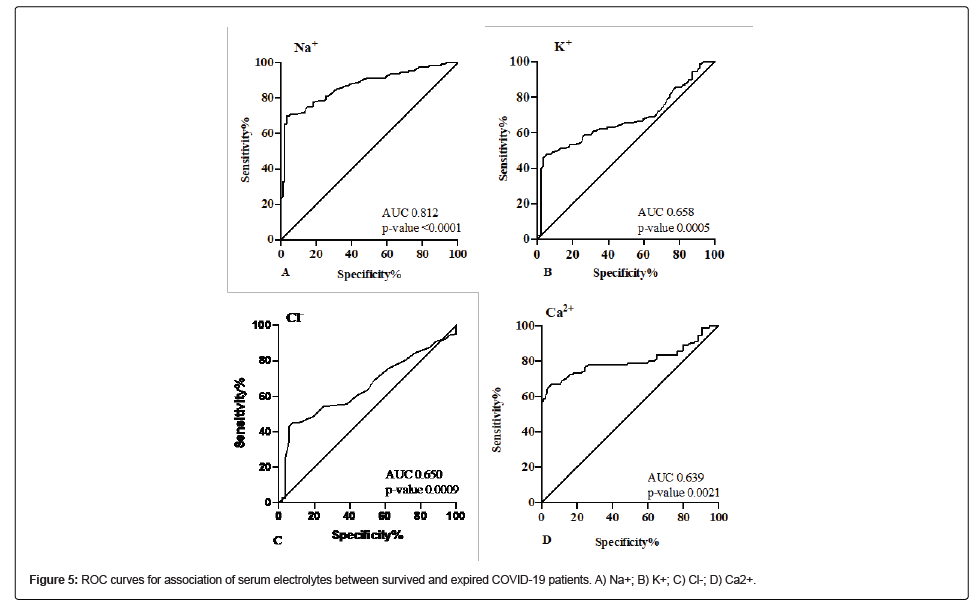

Association of serum electrolytes with disease severity and mortality in COVID-19 patients

Serum electrolytes were also found to be significantly associated with disease severity and mortality in COVID-19 patients (Table 4). The ROC curve for Na+ showed the best cut-off value of 136.5 mmol/L (AUC=0.812, CI 0.752-0.872, p-value<0.0001) with a sensitivity of 76.06% and specificity of 89.47% (Figure 5A). The ROC curve for K+ showed the best cut-off value of 3.7 mmol/L (AUC=0.658, CI 0.568- 0.747, p-value 0.0005) with a sensitivity of 75.18% and specificity of 71.43% (Figure 5B). The ROC curve for Cl- showed the best cut-off value of 101.5 mmol/L (AUC=0.651, CI 0.572-0.731, p-value 0.001) with a sensitivity of 60.56% and specificity of 56.14% (Figure 5C). The ROC curve for Ca2+ showed the best cut-off value of 8.7 mg/L (AUC=0.639, CI 0.561-0.718, p-value 0.002) with a sensitivity of 60.71% and specificity of 62.40% (Figure 5D).

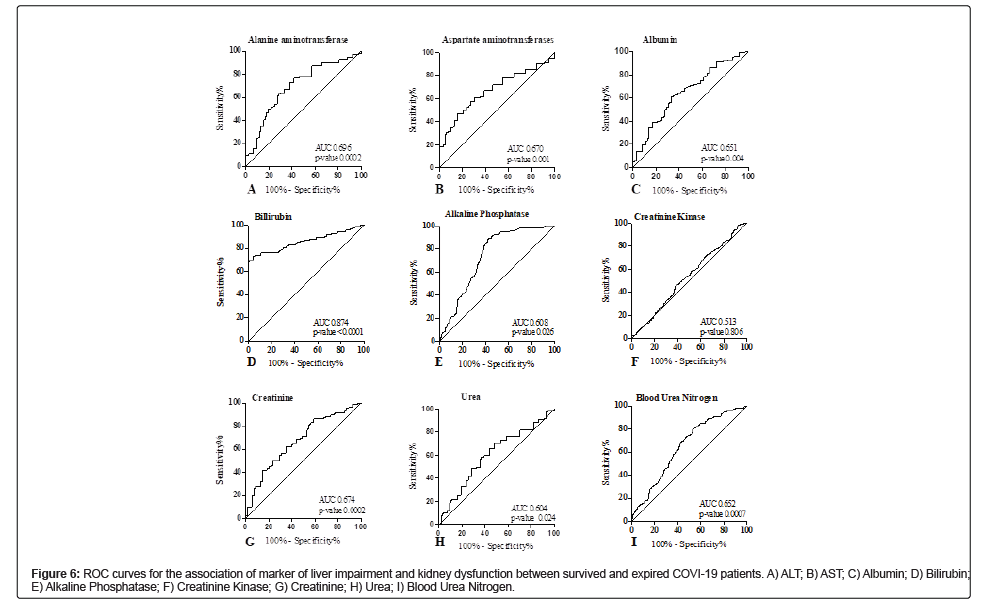

Association of marker of liver impairment and kidney dysfunction with disease severity and mortality in COVID-19 patients

Among markers of liver impairment (Table 4), the ROC curve of ALT depicted the best cut-off value of 19.50 U/L (AUC=0.696, CI 0.603-0.789, p-value 0.0002) with a sensitivity of 72.41% and specificity of 64.29% (Figure 6A). The ROC curve of AST depicted the best cut-off value of 20.56 U/L (AUC=0.670, CI 0.582-0.757, p-value 0.0012) with a sensitivity of 72.17% and specificity of 65.85% (Figure 6B). The ROC curve of albumin depicted the best cut-off value of 27.10 g/L (AUC=0.651, CI 0.552-0.751, p-value 0.0047) with a sensitivity of 65.77% and specificity of 63.89% (Figure 6C). The ROC curve of bilirubin depicted the best cut-off value of 11.80 umol/L (AUC=0.874, CI 0.817-0.930, p-value<0.0001) with a sensitivity of 99.30% and specificity of 70.69% (Figure 6D). The ROC curve of alkaline phosphatase depicted the best cut-off value of 80.50 g/L (AUC=0.608, CI 0.508-0.708, p-value 0.0047) with a sensitivity of 70.30% and specificity of 64.44% (Figure 6E). The muscle marker under observation was creatinine kinase showed no significant association. The ROC curve suggested the cut-off value of 145 U/L (AUC=0.513, CI 0.417-0.61, p-value 0.806) with the sensitivity of 56.01% and specificity of 52.11% (Figure 6F). In ROC analysis of renal dysfunction markers, the best cut-off value for Creatinine was 7.9 mg/L (AUC=0.674, CI 0.591-0.758, p-value 0.0002) with the sensitivity and specificity of 72.93% and 65.45%, respectively (Figure 6G). The best cut-off value for BUN was 3.92 nmol/L (AUC=0.652, CI 0.578- 0.726, p-value 0.0007) with the sensitivity and specificity of 73.43% and 72.41% respectively (Figure 6H). The best cut-off value for uric acid was 7.8 mg/L (AUC=0.891, CI 0.849-0.933, p-value<0.0001) with the sensitivity and specificity of 78.91% and 72.45%, respectively (Figure 6I).

Discussion

The ongoing global pandemic of COVID-19 is due to emergence of a novel infection caused by Sever Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS Cov-2) started from Wuhan China in 2019. Almost every country and territory in the world has been impacted by this disease. World Health Organization (WHO) has reported more that 290 million cases of COVID-19 by the end of December 2021 and 5.4 million deaths [22]. Till date, the world has faced four waves of the infection and three variants of concern known as Alpha, Delta and Omicron. The fifth wave with the emergence of Omicron has started at the end of 2021 [23]. In the first 2 weeks of January 2022 a record number of cases i.e. 15 million cases of COVID 19 cases have been reported to WHO and most of them are infected with omicron [24]. By December 2021, Pakistan has reported 1.3 million cases of COVID 19 with 28,000 deaths which accounts for the 0.5% of the global burden of the infection [25]. Various studies have reported that overall death rate due to COVID-19 varies from 2%-12% in different countries [26,27]. The major cause of death among COVID-19 patients reported in this study and many previous studies is heart attack and multiple organ dysfunction and failure [28]. Furthermore, accurate, rigorous and timely recording and reporting of different aspects of the disease is crucial for determining the disease severity and risk of mortality. Thus, a clear characterization of clinical, radiological, immunological and laboratory parameters is of paramount importance for effective treatment strategies and to reduce the disease severity and risk of mortality.

In this study, we have comprehensively analyzed the correlation of clinical, hematological and biochemical parameters with disease severity and mortality. We have observed that among hospitalized cases, 72% cases (n=143) died due to complication of COVID-19. Among died cases, the proportion of male patients (82%) was significantly higher than female patients and maximum deaths were reported in older people (62%) of age >65 years. The clinical features of COVID-19 patients of the present study were comparable with those of previous studies. Co-morbid conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, chronic lung diseases and cardiovascular diseases were predominately linked with the high risk of disease severity in COVID-19 patients, which was in accordance with the observations of previous published studies [29]. A significant proportion of COVID-19 patients were presented with fever and chest imaging alterations. Clinical outcome of the admitted patients showed that 55% cases were presented with pneumonia, 35% with ARDS and 20% with acute heart injury. The proportion of these outcomes was higher in non-survivors as compared to survivors. The data illustrated that higher body temperature before admission might be a risk factor for disease deterioration in COVID-19 patients. The duration of fever and stay in hospital was longer from onset to hospitalization in non-survivors as compared to survivors (p-value 0.021 and 0.001) respectively which was consistent with a previous study [30]. The survived patients had normal body temperatures within 7 days after admission. Consistent fever during hospitalization might be an indicator of the mortality in COVID-19 patients.

The clinical and radiological parameters of the study cases revealed that fever (p-value 0.0006), cough (p-value 0.032), chills (p-value 0.037), shortness of breath (p-value 0.047) were predominant in non-survivors as compared to survivors. The predominant radiological characteristics of non-survivors were GGO (p-value 0.040), consolidation (p-value 0.023), GGO and consolidation in combination (p-value 0.030). These findings have been reported by many researchers [31-33].

Lymphocytes play a critical role in the viral clearance and preservation of immune system function during an infection [34,35]. Researchers have showed that reduced lymphocyte counts were observed in most severe patients with COVID-19 but remained within the normal range in non-severe patients [36,37]. In the CBC of COVID-19 patients, we found that lymphopenia was the most common in non-survivors than in survivors (0.81 × 109/L vs. 1.5 × 109/L, p-value 0.0003) Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio was also reduced in non-survivors than survivors (16% vs. 24%, p-value 0.005). It is suggested that lymphocytes are directly infected by virus, principally T cell resulting in reduction of CD4+, and CD8+ cells, thus suppressing the immune response [38,39].

Hyperinflammation due to cytokine storm is the hallmark of COVID-19 infection. Among the inflammatory markers, increased levels of CRP (p-value <0.0001), ESR (p-value<0.0001), Ferritin (p-value 0.001), LDH (p-value <0.0001) and PCT (p-value 0.022) were observed in non-survivors were positively correlated with disease severity. Overall, literature evidence suggests that increased levels of various inflammatory markers are associated with disease severity and mortality in the early stage of COVID-19, [40,41]. Another common complication of COVID-19 is a hypercoagulable state, which might promote thrombotic coagulopathies. The underlying pathological mechanisms include infection-related dysfunction of endothelial cells, which causes an increased production of thrombin and inhibition of the fibrinolysis; cardiovascular injury; hyperinflammation state [42,43]. In our patients, increased levels of D-Dimers (p-value 0.0003), Fibrinogen (p-value<0.0001) in COVID-19 patients reflect the coagulation alterations which can increase the risk of ARDS and mortality as reported previously [44,45]. We also observed that increased Prothrombin Time (PT) and decreased activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (aPTT) which has been reported to be associated with disease severity during the early phase of COVID-19 [46].

Electrolyte imbalance in COVID-19 patients has also been reported by many studies to be associated with disease severity particularly hyponatremia, hypokalemia, and hypocalcemia [39,47]. Our findings were also in agreement with previous studies as we also observed decreased levels of potassium (p-value 0.0004), sodium (p-value<0.0001), chloride (p-value 0.0011) and calcium (p-value 0.0021) but increased level of magnesium (p-value 0.0002) in serum of COVID-19 patients who did not survive. Our data suggests that increased levels of CK (p-value 0.048) and troponin (p-value<0.0001) in non-survivor cases could be a direct effect of the SARS-CoV-2, which can also infect cells of the muscle tissue due to the expression of the ACE2 receptor. Typically, increased levels of biomarkers of muscle injury such as creatinine kinase and troponin are related to kidney dysfunction and cardiac injury [48].

Another common laboratory finding is the alteration of hepatocytic biomarkers such as ALT, AST, albumin, alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin. We found the increased levels of all these biomarkers in nonsurvivor COVID-19 patients. Although the underlying mechanism of this alteration is not well depicted but higher levels of biomarkers related to liver dysfunction have been observed to be linked associated with severity and mortality due to COVID-19 [48]. Multiple studies have demonstrated that alterations in renal biomarkers, as depicted by raised levels of serum creatinine, in COVID-19 patients. The virus can could directly infect kidney tubular cells expressing the ACE2 receptor on their cellular surface. According to an Italian report, about 25%-30% of deaths due to COVID-19 are due to Acute Kidney Injury (AKI). Our findings of the study are also in pertinent with the observation reported by other researchers globally.

Conclusion

For the pertinent diagnosis and treatment management of COVID-19, the laboratory medicine plays a key role. The SARSCoV- 2 infection is characterized by several biochemical alterations, which can be recognized by specific biomarkers helping clinicians to clinch requisite clinical monitoring for an ameliorate clinical outcome. Among all biomarkers associated with disease severity and mortality lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, CRP, ESR, PCT, LDH, AST, ALT, D-dimer, CK, albumin, creatinine phosphatase represents the most predictive parameters of severe COVID-19 infection.

Limitation of the Study

The major limitation of the present study is that the data presented is of a single hospital with relatively small number of non-survivor cases. Due to this limitation, the proportion of some clinical manifestations of the patients might be different from the reports from other cohort studies with large sample size. Therefore, a cohort study with large numbers of patients is needed to verify our conclusions.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by Institutional Ethical Review Board (IERB) of Allama Iqbal Medical College/Jinnah hospital, Lahore (Ref No. 8/15/12/2020/S2/ERB) in 79th meeting of the board. Participant confidentiality was maintained throughout the investigation. All subjects who participate in the investigation were assigned a study identification number by the investigation team for the labelling of questionnaires and specimens. As this was a retrospective study using patient data form hospital record, so patient’s consent was not required. The study was only approved by IERB.

Consent for publication

All authors have consented for this publication.

Available Data and Materials

The data can be obtained from corresponding author on reasonable request and through the permission or approval of ethical review board.

Competing Interest

None

Funding

This study did not receive any funding in partial or whole.

Author Contribution

Conceptualization: AK, FA ; Data Curation: AK, FA, HA, ST, SJ, SS ; Formal Analysis: AK, HA, SS ; Investigation: AK, FA, HA, ST, SJ, SS ; Methodology: AK, FA, HA, ST, SS ; Project Administration: AK, FA, HA, ST, SJ ; Resources: AK, FA ; Supervision: AK, FA ; Validation: AK, FA, SS ; Visualization: AK, FA, SS ; Writing-original draft: AK, SS ; Writing review and editing: AK, FA, SS

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Muhammad Tajjamul, Muhammad Asim and Saima Anwer or helping in data acquisition.

References

- Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, et al. (2020) Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet 395:507-513.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ge H, Wang X, Yuan X, Xiao G, Wang C, et al. (2020) The epidemiology and clinical information about COVID-19. EurJ Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 39:1011-1019.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Adhikari SP, Meng S, Wu Y, Mao Y, Ye R, et al. (2020) Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infect Dis Poverty 9:1-12.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- CDC (2021) National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD), Division of Viral Diseases.

- Zheng Y, Sun L, Xu M, Pan J, Zhang Y, et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics of 34 COVID-19 patients admitted to intensive care unit in Hangzhou, China. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 21:378-387.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang F, Liu J, Zjang P, Jiang W, Zhang L, et al. (2020) Expert consensus on prevention and control of COVID-19 in the neurological intensive care unit (first edition). Stroke Vasc Neurol 5:242-249.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zeng F, Huang Y, Guo Y, Yin M, Chen X, et al. (2020) Association of inflammatory markers with the severity of COVID-19: A meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 96:467-474

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 395:497-506.

- Chang HL, Chen K, Lai S, Kuo H, Su I, et al. (2006) Hematological and biochemical factors predicting SARS fatality in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc 105:439-450.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu L, Mao Y, Chen G (2020) Risk factors for 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) patients progressing to critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging (Albany NY) 12:12410.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Qian GQ, Yang N, Ding F, Ma AHY, Wang Z, et al. (2020) Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of 91 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Zhejiang, China: a retrospective, multi-centre case series. QJM Int J Med 113:474-481.

- Samprathi M, Jayashree M (2021) Biomarkers in COVID-19: An Up-To-Date Review. Front Pediatr 8:607-647.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang JT, Sheng W, Fang C, Chen Y, Wang J, et al. (2004) Clinical manifestations, laboratory findings, and treatment outcomes of SARS patients. Emerg Infect Dis 10:818-824.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tjendra Y, Mana AF, Espejo AP, Akgun Y, Millan NC, et al. (2020) Predicting Disease Severity and Outcome in COVID-19 Patients: A Review of Multiple Biomarkers. Arch Pathol Lab Med 144:1465-1474.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wen Xs, Jiang D, Gao L, Zhou J, Xiao J, et al. (2021) Clinical characteristics and predictive value of lower CD4+T cell level in patients with moderate and severe COVID-19: A multicenter retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis 21:57.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ejaz H, Alsrhani A, Zafar A, Javed H, Junaid K, et al. (2020) COVID-19 and comorbidities: Deleterious impact on infected patients. J Infect Public Health 13:1833-1839.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Singh AK, Gillies CL, Singh R, Singh A, Chudasama Y, et al. (2020) Prevalence of co-morbidities and their association with mortality in patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab 22:1915-1924.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alamin AA, Yahia AIO (2021) Hematological parameters predict disease severity and progression in patients with COVID-19: A Review Article. Clin Lab 67.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- China (2020) Notice on the novel coronavirus infection diagnosis and treatment plan (trial version sixth). In: National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China, editor.

- RT-PCR- NG (2020) National testing guidelines for RT-PCR.

- WHO (2022) COVID-19 dashboard.

- CDC (2021) Centre for Disease Control and Prevention.

- NIH (2022) National Institute of Health.

- Mahase E (2020) Coronavirus: COVID-19 has killed more people than SARS and MERS combined, despite lower case fatality rate. BMJ 368:m641

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yang X, Yu Y, Cu J, Shu H, Xia J, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. 8:475-481.

- Carlos WG, Cruz CSD, Cao B, Pasnick S, Jamil S (2020) Novel Wuhan (2019-nCoV) Coronavirus. Am J Rspir Crit Care Med P7-P8.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tian W, Jiang W, Yao J, Nicholson CJ, Li RH, et al. (2020) Predictors of mortality in hospitalized COVID‐19 patients: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. 92:1875-1883.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li X, Xu S, Yu M, Wang K, Tao K, et al. (2020) Risk factors for severity and mortality in adult COVID-19 inpatients in Wuhan. 146:110-118.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Durrani M, Haq I, Kalsoom U, Yousaf A (2020) Chest X-rays findings in COVID 19 patients at a University Teaching Hospital - A descriptive study. Pak J Med Sci 36: S22-S26.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wong HYF, Lam HYS, Fong AH, Leung ST, Chin TW, et al. (2020) Frequency and distribution of chest radiographic finding and distribution in COVID-19 positive patients. Radiology 296:E72-E78.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, Tian F, Jin D, et al. (2020) Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. 32:1406-1407.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yap K, Ada G, McKenzie IJN (1978) Transfer of specific cytotoxic T- lymphocytes protects mice inoculated with influenza virus 273:238-239.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sitati EM, Diamond MS (2006) CD4+ T-cell responses are required for clearance of West Nile virus from the central nervous system. J Virol 80:12060-12069.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang F, Hou H, Luo Y, Tang G, Wu S, et al. (2020) The laboratory tests and host immunity of COVID-19 patients with different severity of illness. JCI Insight 5:e137799.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chang D, Lin M, Wei L, Xie L, Zhu G, et al. (2020) Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of novel coronavirus infections involving 13 patients outside Wuhan, China. JAMA 323:1092-1093.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang G, Zhang J, Wang B, Zhu X, Wang Q, et al. (2020) Analysis of clinical characteristics and laboratory findings of 95 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A retrospective analysis. Respir Res 21:74.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fu L, Wang B, Yuan T, Chen X, Ao Y, et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. J Infect 80:656-665.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, Liang W, Ou C, et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics of 463 patients with common and severe type coronavirus disease. N Engl J Med 2002032.

- Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z, Zhang S, Yang S, et al. (2020) Dysregulation of immune response in patients with coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China. 71:762-768.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, Chuich T, Dreyfus I, et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 75:2950-2973.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Levi M, Poll TV (2017) Coagulation and sepsis. Thrmob Res 149:38-44.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, Xia J, Zhou X, et al. (2020) Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med 180:934-943.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhou F, Fan G, Liu Z, Cao B (2020) SARS-CoV-2 shedding and infectivity–Authors' reply. Lancet 395:10233.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, et al. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost 18:1094-1099.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lippi G, South AM, Henry BM (2020) Electrolyte imbalances in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Ann Clin Biochem 57:262-265.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lippi G, Plebani M (2020) The critical role of laboratory medicine during coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and other viral outbreaks. Clin Chem Lab Med 58:1063-1069.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, Zhang J, Huang L, et al. (2020) Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. 8:420-422.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- News (2020) The report to parliament.

Citation: Khaliq A, Ashraf F, Tahir S, Javed S, Shahid S, et al. (2022) Clinical and Biochemical Predictors of Mortality of COVID-19 Cases from Pakistan. J Infect Dis Ther 10: 502. DOI: 10.4172/2332-0877.1000502

Copyright: © 2022 Khaliq A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 2259

- [From(publication date): 0-2022 - Nov 21, 2024]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 2012

- PDF downloads: 247