Bullying Behavior Roles And Mental Health Correlates Among Secondary School Students In Ilesa, Nigeria

Editor assigned: 01-Jan-1970 / Reviewed: 01-Jan-1970 / Revised: 01-Jan-1970 /

Abstract

Objective: Bullying behaviour is pervasive, cuts across age group, transcends geographical location and its impacts include but not limited to physical or academic snags. The objective of the study is to determine bullying roles and their association with emotional or behavioural problems among adolescents in Ilesa, Nigeria.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was performed on 432 senior secondary school students (12-18 years old) in Ilesa (Nigeria). Peer Relationship Questionnaire was used to determine bullying roles and the Strength and Difficulty Questionnaire to measure behavioural problems.

Results: Prevalence of bullying behaviour is high. The bully-victims had the highest means score on all subscales except pro-social. Similarly, the bully-victims was significantly associated with all subscales of the SDQ except the pro-social problems at (P< .001), (P=.024), (P= .004), (P= .004), and (P< .001) for conduct, emotional problem, hyperactivity problem, peer relationship problem and the total difficulty score respectively.

Conclusion: This shows that participating in bullying behaviour irrespective of the role played increases the likelihood of psychological consequences, especially the bully-victim. There is a need to establish anti-bullying programs in schools to curb this menace and its mental health consequence.

Keywords

Bullying • Bully-victims • Psychiatric morbidity • Depression

Introduction

Bullying as a contemporary issue of public health importance is an undesired, repeated intentional harm to an individual who is not capable of defending himself. It is a form of aggressive behavior in which there is a perceived or real imbalance of power [1]. Bullying occurs in diverse settings such as schools and the workplace. Identified specific acts of bullying include; making threats, spreading rumors, physical and or verbal attacks, or excluding the individual from a group intentionally [2]. Bullying is a global menace with distressing experiences that are often continuous over years with a predilection for both concurrent and future psychiatric symptoms and disorders [3]. The mental health of children and adolescents has increasingly become an issue of public interest [4]. Efforts are being made at early detection; however, there is a treatment gap as only a few of the adolescents that need specialized care can receive it [5]. Several factors have been implicated as being associated with emotional and behavioral problems. School bullying has been implicated as a threat to the physical and mental or emotional wellbeing of student independent of the roles played [6]. Hence, the need to find the relationship between bullying behaviors and emotional disorders or behavioral problems. Being a victim of bullying has been associated with reduced self-esteem [7], anxiety and depressive symptoms [8,9], physical and psychosomatic symptoms [9], suicidal ideation [10], and suicide [1]. On the other hand, being a perpetrator has been associated with aggression [11], antisocial personality, criminality, and substance abuse [12]. Adolescents involved in bullying (either as perpetrators or as victims or both) are at significant risk of experiencing psychiatric symptoms [3], alcohol and drug abuse, and suicidal ideation or behavior [13]. Some studies have found associations between conduct problems and bullying [14]. Specifically, youth who are perpetrators have reported high levels of conduct-disordered behavior [15]. Perpetrators of bullying exhibit more antisocial behavior and physical aggression than non-bullies but they exhibit lower levels of anxiety [16]. Depression and suicidal tendency have also been documented to be predictors of both bullying and victimization [17]. Also, it has been demonstrated that children with developmental disorders such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and physical disabilities are at risk of victimization [18]. There are pieces of evidence emanating from developed countries highlighting the adverse consequences on the individuals involved in bullying, either as a victim or as a perpetrator, and or both [3,8], there have been few reports on bullying in schools from Nigeria [19]. Also, none has explored the relationship between bullying and psychiatric morbidities concerning roles in bullying behavior. This current study was carried out to fill this gap in knowledge. Our study aimed to determine the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among subgroups of bullying behavior (perpetrator, victim, bully/victim, and uninvolved) among senior secondary school students in Ilesa, Nigeria. We set out to test these hypotheses “bully-victims will have a higher prevalence of emotional problem compared with other subgroup involved in bullying behavior”, and “bully-victims will have a higher mean score on total difficulty score compared to other subgroups in bullying behavior, “there will be significant differences in the mean scores between the bully-victims and the victims'

Materials and Methods

Study site

The study was a cross-sectional descriptive study conducted among senior secondary school students from selected schools in the two local government areas in Ilesa, Osun state. A total of 43 senior secondary schools existed in the two Local Government Areas (LGAs) in Ilesa.

Study population

Study participants were selected by the multistage sampling technique. The ownership of the institutions (‘public’ and ‘private’) was the first criteria for stratification. There are twelve public and twelve private senior secondary schools in Ilesa East Local Government Area, while there are nine public and ten private senior secondary schools in Ilesa West Local Government. Hence, three public and three private senior secondary schools were randomly selected from each of the two Local Government Areas. An earlier survey carried out reveals a minimum of two arms per class. Two arms were randomly selected from each class (i.e., SSI, SSII, and SSIII), making a total of 6 arms per school. Six students in each arm were determined using a yes or no ballot with only six “yes” options. This was done for those who met the inclusion criteria. The twelve students selected in each of the secondary school classes (i.e. SSI, II, and III) were selected to reflect the male-to-female ratio of the student population in that class. Thirty-six students selected in each school were asked to sit inside a hall or an empty classroom within their school premises and asked to fill the self-administered questionnaires away from their teacher’s interference.

Study instrument

The research instrument used was a questionnaire comprising of three sections, a semi-structured socio-demographic part, “Peer Relationship Questionnaire” (PRQ) [20] and “Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire” (SDQ) [21]. The suitability of the instrument was explored via a pilot study conducted among a sample of students from one of the schools not selected for the main study.

The socio-demographic questions included questions such as age as at last birthday, gender, class at senior secondary school, type of institution, socioeconomic status of parents. A shorter version of the PRQ which is a 12 item instrument, self-report questionnaire was used to assess bullying, victimization and pro-social behavior among children between the ages of 12 to 18 years. The items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale (1=Never, 2=Once in a while, 3=Pretty often to 4=Very often). This score is dichotomized as bully/ Non-bully; scores of seven and above indicate being a bully (perpetrator). Victims are individuals with a score of six and greater. The reliability of the PRQ was assessed. The Cronbach alpha for the bully and victim subscales were 0.75 and 0.82 which exceeded 0.70 as reported by Slee and Rigby the original designer of the questionnaire [21].

Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) was used to determine the risk for psychiatric morbidity among the respondents. It consists of 25 items, grouped into five clinical scales: (1) hyperactivity/inattention, (2) emotional symptoms, (3) conduct problems, (4) peer relationship problems, and (5) prosocial behavior. Each of the clinical scales has 5 items. Using the various cutoff points recommended by Goodman [21], children were classified into not likely, borderline risk and substantial risk on each of the sub-scales of SDQ. Under the emotional symptoms sub-scale of SDQ, a score of 0-5 means it is unlikely there is a problem; a score of 6 is a borderline risk, while 7-10 indicate a substantial risk of emotional problem. For the conduct problem subscale of SDQ, a score of 0-3 indicate conduct disorder is unlikely; a score of 4 is classified as borderline risk, while scores of 5-10 indicate substantially significant risk for conduct problems. For the hyperactivity clinical scale of SDQ, scores of 0-5 indicate hyperactivity is unlikely, a score of 6 is classified as borderline risk, and scores of 7-10 indicate substantial risk of hyperactivity. On the peer problem sub-scale of SDQ, scores of 0-3 are not indicative of peer problem; scores of 4-5 are classified as borderline risk, while scores of 6-10 indicate substantial risk for peer problem. Regarding the pro-social behavior sub-scale, scores of 6-10 indicate the child is unlikely to have a problem. A score of 5 indicates a borderline risk while scores of 0-4 mean there is a likelihood of poor social behavior. Total Difficulty Score of SDQ was determined, which is the sum of all values in each sub-scale except the prosocial sub-scale hence will have a maximum score of 40. Values of 20-40 on the total difficulty score indicate a significant risk of psychiatric morbidity; 16-19 is a borderline risk, while 0-15 indicates a problem is unlikely [22]. In this study, the scores were further dichotomized as risk-prone to include “borderline and risk-prone” and the not likely as a separate group. The self-rated version of the SDQ was used for this study.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics and Research Committee of the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex (OAUTHC), Ile Ife. Written permission was obtained from the Local Inspector of Education in each of the Local Government Areas involved. Written informed consent was obtained from the subjects and parents of each respondent. Participation was voluntary and confidentiality was assured.

Data analysis

Data analysis was done using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 25). The socio-demographic details of respondents were reported using descriptive statistics such as frequency, means, and standard deviation (SD). The confidence interval was set at 95% and all tests were twotailed. Statistical significance was considered at a p-value of less than 0.05.

Results

The total number of participants was four hundred and forty-two (432). The age of participants ranged between 12 and 18, with (mean=15.32, SD= ± 1.58 years). The females were 225 (52.1%), majority 381 (88.1%) belonged to socioeconomic class 3.

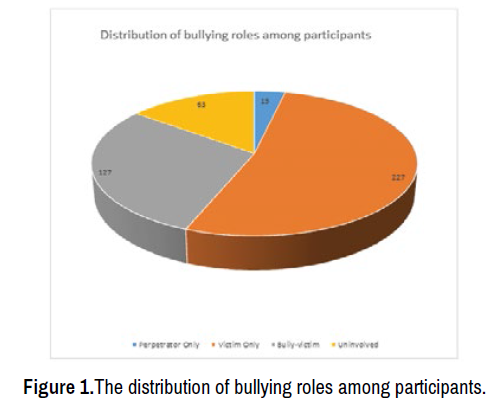

The prevalence of bullying in the study is 85.4% either as a victim, perpetrator, or both (Figure 1), depicts the bullying roles with the majority 227(52.5%) being victims only, 15(3.5%) perpetrators only, 127 (29.4%) represents the bully/victims and 63(14.6%) are uninvolved in bullying activity.

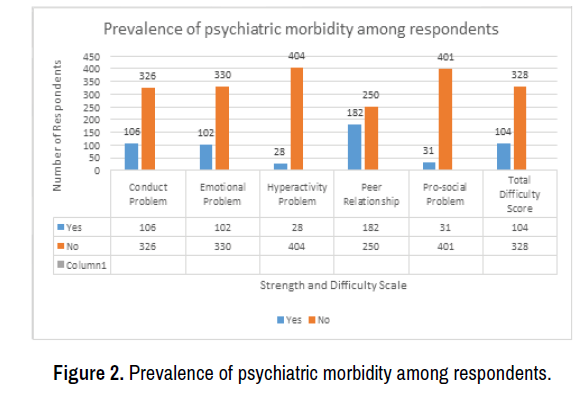

The total difficulty score of the Strength and Difficulty Questionnaires (SDQ) reveals that 104 (24.1%) respondents had psychiatric. Figure 2 shows the proportions of respondents with different degrees of presence or absence of various forms of psychiatric morbidities.

The highest proportion of respondents (182 of 432, 42.1%) had problems relating to their peers.

Table 1 shows the prevalence of the subscales of SDQ comparing the various roles played in bullying. The bully-victim have the highest prevalence of all subscales except for peer problem and the pro-social subscale thus responding to the first hypothesis that “bully-victims will have a higher prevalence of emotional problem compared with other subgroup involved in bullying behavior.” Hence this study fails to accept the hypothesis.

| SDQ subscales | Perpetrator N=15 | Victim only N=227 | Bully-victim N=127 | Uninvolved N=63 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Emotional | 4 | 26.7 | 52 | 21.5 | 35 | 31.3 | 11 | 17.5 |

| Conduct | 4 | 26.7 | 47 | 19.4 | 46 | 41.1 | 9 | 14.3 |

| Hyperactivity | 1 | 6.7 | 13 | 5.4 | 14 | 12.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Peer problem | 8 | 53.3 | 96 | 39.7 | 59 | 52.2 | 19 | 30.2 |

| Pro-social | 1 | 6.7 | 11 | 4.5 | 4 | 3.6 | 4 | 6.3 |

| Total difficulty score | 3 | 20 | 46 | 19 | 46 | 41.1 | 9 | 14.3 |

Table 1. Prevalence of being behavior and emotional problems on the subscales of SDQ according to their bullying behavior role.

Mean scores of all bullying behavior roles were compiled, the perpetrators who are at the same time victims (bully-victims) have the highest mean score on total difficulty score, emotional problem as well as other subscales of SDQ except for peer relationship problem and the pro-social problem. Table 2 shows the first hypothesis that “bully-victims will have the highest mean on the emotional problem scale compared with other players in bullying behavior”. This study fails to accept the null hypothesis.

| SDQ subscales | Perpetrator | Victim only | Bully-victim | Uninvolved | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Emotional | 4 | 2.14 | 3.61 | 2.34 | 4.16 | 2.34 | 3.35 | 2.39 |

| Conduct | 2.13 | 1.89 | 2.01 | 1.73 | 3.08 | 2.25 | 1.83 | 1.71 |

| Hyperactivity | 2.6 | 1.35 | 2.24 | 1.75 | 3.2 | 1.9 | 2.25 | 1.51 |

| Peer problem | 4 | 2.07 | 2.98 | 1.72 | 3.71 | 1.97 | 2.83 | 2 |

| Pro-social | 8.2 | 2.24 | 8.61 | 1.74 | 7.96 | 1.93 | 8.84 | 1.6 |

| Total difficulty score | 12.73 | 5.02 | 10.85 | 5.39 | 14.15 | 5.99 | 10.25 | 5.14 |

Table 2. Mean scores of subscales of SDQ according to bullying behavior role.

The comparison of the mean scores of bully-victim and victims was made regarding the strength and difficulty questionnaire. The result reveals a statistically significant difference occurs on all subscales of the SDQ. Table 3 confirms the third hypothesis that will be a statistically significant difference in the mean score of bully-victims and victims only. This study fails to accept the third hypothesis.

| Subscales | Mean | SED | t | Sig |

| Emotional | 0.55 | 0.27 | 2.057 | 0.04 |

| Conduct | 1.07 | 0.22 | 4.904 | <.001 |

| Hyperactivity | 0.96 | 0.21 | 4.67 | <.001 |

| Prosocial | -0.65 | 0.206 | -3.156 | 0.002 |

| Peer problems | 0.73 | 0.206 | 3.544 | <.001 |

| Total difficulty score | 3.3 | 0.638 | 5.169 | <.001 |

| SED: Standard Error of the Difference | ||||

Table 3. Difference in the mean score between bully-victims and victims.

This study shows that about one-third 133(30.1%) of the respondents had behavioral problems determined by the total difficulty score of the Strength and Difficulty Questionnaires (SDQ). With 78(60.5%) of the bully-victim having mental health problems, compared with 55(18.0%) for the other subgroups (p<.001), indicating a statistically significant association between bully-victim and the total difficulty score which supports the fourth hypothesis that the bully-victim sub-group will be associated with the total difficulty score, hence this study fails to accept the null hypothesis. Close to four in ten (39.4%) of the individuals who are bully-victims had conduct problems, compared with 18.4% in the other bullying behavior roles. Hence bully-victim is significantly associated with conduct problems (p<0.001). This is seen in Table 4.

| SDQ subscales | Bully-victim N=127(%) | Other bullying roles N=305(%) | X2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conduct | Yes | 50(39.4) | 56(18.4) | 21.374 | <.001 |

| No | 77(60.6) | 249(81.6) | |||

| Emotional | Yes | 39(30.7) | 63(20.7) | 5.024 | 0.024 |

| No | 88(69.3) | 242(79.3) | |||

| Hyperactivity | Yes | 15(11.8) | 13(4.3) | 8.429 | 0.004 |

| No | 112(88.2) | 292(95.7) | |||

| Peer relationship | Yes | 67(52.8) | 115(37.7) | 8.331 | 0.004 |

| No | 60(47.2) | 190(62.3) | |||

| Pro-social | Yes | 122(96.1) | 296(97.0) | 0.278 | 0.597 |

| No | 5(3.9) | 9(3.0) | |||

| Total difficulty score | Yes | 78(61.4) | 55(18.0) | 79.202 | <.001 |

| No | 49(38.6) | 250(82.0) | |||

Table 4. Association between bully-victim and SDQ (mental health problems).

Discussion

This study has shown that bullying is highly prevalent among secondary school students in Ilesa, Nigeria. The overall prevalence of ever engaging in bullying behavior irrespective of the roles played was 85.4 percent. These findings are in line with the prevalence of bullying behavior reported by Egbochukwu in 2007 among secondary school students in Benin City, Edo state [23]. He reported that 85 percent of the students had bullied before and 78 per cent of them had been victims of bullying. Another researcher studied victimization among secondary school students in Ile-Ife in the preceding one year before the study and reported a prevalence of 72.3 percent [24]. Close to a third of these respondents are bully-victims, with no result to compare within this clime hence this study fills the knowledge gap.

In this study, the overall rate of risk of psychiatric morbidity using the total difficulty score was 24.1 percent, while the risk on the sub-scales were 6.5, 24.5, 33.6, 42.1 and 7.1 per cent for hyperactivity, conduct problems, emotional problems, peer relationship problem and the pro-social sub-scales respectively. The findings of a previous report in which a similar instrument was utilized in five developing countries, including Nigeria, reported a range of between 5.8 percent and 15 per cent with conduct and emotional problems being the two sub-scales with higher rates compared with others [25]. However, another researcher in Nigeria used the same instrument among children with intellectual disability and reported a higher prevalence of 48 percent when borderline risk and substantial risk were added [2]. The Federal Government of Nigeria reported a prevalence rate of psychiatric morbidity among adolescents as ranging between 10 and 18 percent, [26] which is similar to observations from other developing countries [19], and developed countries from which a range of 10 and 30 per cent have been reported [19]. The observations indicate that psychiatric morbidity is higher among school children irrespective of the economic status of the country of residence.

This study supports the findings of several authors, Kumpulainen and colleagues in 1999 opined that bullying behavior is associated with a significant level of psychiatric morbidity [27]. It was observed that there were higher mean scores in all sub-scales of psychiatric morbidity among perpetrators, victims and bully-victims than the uninvolved counterparts, except for the pro-social subscale. This is similar to the findings by Wolke and colleagues who documented that the children involved in bullying had increased behavioral problems than non-perpetrators [28]. The authors also concluded that all groups involved in bullying had significantly higher scores than non-perpetrators on total difficulties, conduct problems, and hyperactivity but lower scores than neutral children for pro-social behavior [28]. Also, victims in their study reported more peer problems than non-victims. Perpetrators with relatively very high scores on hyperactivity and conduct problems and least score on pro-social behavior were at increased risk of life persistent antisocial behavior [29].

Bullies and bully-victims were found to behave generally more aggressive than their peers [30]. This study shows perpetrators to have a high score on conduct, hyperactivity, and emotional scales which is similar to reports of some authors. This study also found that perpetrators have a low score on the prosocial scale, which implies their unfriendly and unfavorable disposition towards peers. Perren and colleagues in 2010 noted that perpetrators are violent, intimidating, and unsympathetic toward peers hence they score higher on conduct and hyperactivity symptoms. They also show features of anxiety and feel insecure resulting in high scores on the emotional scale [31].

Victims were described as depressed, withdrawn, anxious, and insecure. Victims in this study score higher on internalizing (emotional and the peer problem) scale compared with their uninvolved counterparts. Hence, they appear quieter than other students similar to the findings by Kumpulainen and colleagues [27].

Bully-victims have been described as the most distressing of the roles, in our study they scored highest on both conduct and hyperactivity scales like the perpetrator and emotional scales like the victims. Implying that they suffer the consequences of being a perpetrator as well as being a victim [12]. Similar to perpetrators only in other studies, they demonstrate high levels of physical and verbal aggression [27]. They scored high on measures of both externalizing and hyperactive behavior but also on measures of depression, self-worth, academic competence, and social acceptance [12]. Both bullies and bullyvictims were found to behave generally more bellicosely than their peers [30].

Bully-victims were noted to be risk-prone to psychological adverse effects. Also similar to the finding by Kim et al. in a follow-up study that documented the bully-victim group was the most vulnerable group for developing multiple psychopathological complications than their uninvolved peers [11].

Conclusion

Going by the high rates of bullying behavior observed among the students in this study. Attention should be paid to individuals who engage in bullying behavior particularly the bully-victims. Childhood bullying is a multifaceted behavior with potentially serious consequences including a higher risk of psychiatric morbidity than uninvolved counterparts. Thus early identification of children at risk should be of utmost importance in our society. It is recommended that anti-bully programs should be adopted in schools to make the school environment friendlier and mental health promotion programs should be included in the school curriculum to improve student-student and student-teacher interactions.

Limitations

1. The limitations of the study included only school-attending adolescents were involved in the study.

2. The screening tool was used during the study to assess psychiatric morbidity; hence, valid psychiatric diagnoses were not made.

References

- Klomek, Anat Brunstein, Sourander Andre, Niemelä Solja and Kumpulainen Kirsti, et al. “Childhood Bullying Behaviours As a Risk for Suicide Attempts and Completed Suicides: A Population-Based Birth Cohort Study.” J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 48(2009): 254-261.

- Bakare, Muideen O, Ubochi Vincent N, Ebigbo Peter O and Orovwigho Andrew O. “Problem and Pro-Social Behaviour Among Nigerian Children With Intellectual Disability: The Implication for Developing Policy for School-Based Mental Health Programs.” Ital J Pediatr 36(2010): 37-43.

- Landstedt, Evelina and Persson Susanne. “Bullying, Cyber bullying, and Mental Health in Young People.” Scand J Public Health 42(2014):393-399.

- Blanco, Carlos, Wall Malanie M, He Jian-Ping and Krueger Robert F, et al. “The Space of Common Psychiatric Disorders in Adolescents: Comorbidity Structure and Individual Latent Liabilities.” J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 54(2015): 45-52.

- Costello, E Jane, Copeland William and Angold Adrian. “Trends in Psychopathology Across the Adolescent Years: What Changes When Children Become Adolescents, and When Adolescents Become Adults?” J Child Psychol Psychiatry 52(2011): 1015-1025.

- Tsitsika, Artemis Kimon, Barlou Efi, Andrie Elisabeth and Dimitropoulou Christine, et al. “Bullying Behaviours in Children and Adolescents: “An Ongoing Story.” Front public Heal 2(2014).

- Delfabbro, Paul, Winefield Tony, Trainor Sarah and Dollard Maureen, et al. “Peer and Teacher Bullying/Victimisation of South Australian Secondary School Students: Prevalence and Psychosocial Profiles.” Br J Educ Psychol 76(2006): 71-90.

- Abada, Teresa, Hou Feng and Ram Bali. “The Effects of Harassment and Victimization on Self-Rated Health and Mental Health among Canadian Adolescents.” Soc Sci Med 67(2008): 557-567.

- Lien, Lars, Green Kristian, Welander-Vath Audun and Bjertness Espen. “Mental and Somatic Complaints Associated With School Bullying 10th and 12th-Grade Students From Cross-Sectional Studies in Oslo, Norway.” Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Heal 5(2009): 6.

- Skapinakis, Petros, Bellos Stefanos, Gkatsa Tatiana and Magklara Konstantina, et al. “The Association between Bullying and Early Stages of Suicidal Ideation in Late Adolescents in Greece.” BMC Psychiatry 11(2011): 22.

- Kim, Young Shin, Leventhal Bennett L, Koh Yun Joo and Hubbard Alan, et al. “School Bullying and Youth Violence: Causes or Consequences of Psychopathology?” Arch Gen Psychiatry 63(2006): 1035-1041.

- Sourander, Andre, Jensen Peter, Ronning John A and Elonheimo Henrik, et al. “Childhood Bullies and Victims and Their Risk of Criminality in Late Adolescence.” Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 161(2007): 546-552.

- Klomek, Anat Brunstein, Marrocco Frank, Kleinman Marjorie and Schonfeld Irvin, et al. “Bullying, Depression and Suicidality in Adolescents.” J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 46(2007): 40-49.

- Nansel, Tonja R, Overpeck Mary, Pilla Ramani S and Ruan W June, et al. “Bullying Behaviours among US Youth.” JAMA 285(2001): 2094.

- Kokkinos, Constantinos M and Panayiotou Georgia. “Predicting Bullying and Victimisation among Early Adolescents: Associations with Disruptive Behaviour Disorders.” Aggress Behav 30(2004): 520-533.

- Whitney, Irene and Smith Peter. “A Survey of the Nature and Extent of Bullying in Junior Middle and Secondary Schools.” Educ Res 35(1993):3-25.

- Brockenbrough, Karen K, Cornell Dewey G and Loper Ann. “Aggressive Attitudes among Victims of Violence at School.” Educ Treat Child 25(2002): 273-287.

- Skinner, Rosemary and Piek Jan. “Psychosocial Implications of Poor Motor Coordination in Children and Adolescents.” Hum Mov Sci 20(2001): 73-94.

- Mba, N, Famuyiwa OO and Aina O. “Psychiatric Morbidity in Two Urban Communities in Nigeria.” East Afr Med J 85(2009): 368-377.

- Rigby, Ken and Slee Philip. “Dimensions of Interpersonal Relating to Australian School Children and their Implications for Psychological Well-Being.” J Sch Psychol 133(1993): 33-42.

- Goodman, Robert. “The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A Research Note.” J Child Psychol Psychiatry 38(1997): 581-586.

- Grigsby, Jim and Stevens David. “The Neurodynamics of Personality. New york: Guilford.” (2000).

- Egbochukwu, EO. “Bullying in Nigerian Schools: Prevalence Study and Implication for Counselling.” J Soc Sci 14(2007): 65-71.

- Ehindero, Serifat Adefunke. “Types and Prevalence of Peer Victimisation among Secondary School Students in Osun State.” Int J Cross-Disciplinary Subj Educ 1(2010): 53-60.

- Atilola, Olayinka, Singh Balhara, Yatan Pal and Stevanovic Dejan, et al. “Self-Reported Mental Health Problems among Adolescent in Developing Countries.” J Dev Behav Pediatr 34(2013)12-4.

- Federal Ministry of Health N. Mental Health Policy (1991).

- Kumpulainen, Kirsti, Rasanen Eila and Henttonen Irmeli. “Children Involved in Bullying: Psychological Disturbance and the Persistence of Involvement.” Child Abus Negl 23(1999): 1253-1262.

- Wolke, Dieter, Woods Sarah, Bloomfield Linda and Karstadt Lyn. “The Association between Direct and Relational Bullying and Behaviour Problems among Primary School Children.” J Child Psychol Psychiatry 41(2000): 989-1002.

- Lahey, Benjamin B, Waldman Irwin D and McBurnett Keith. “The Development of Antisocial Behaviour: An Integrative Causal Model.” J Child Psychol Psychiatry 40(1999): 669-682.

- Perren, Sonja and Alsaker Francoise. “Social Behaviour and Peer Relationships of Victims, Bully-Victims, and Bullies in Kindergarten.” J Child Psychol Psychiatry 47(2006): 45-57.

- Perren, Sonja, Dooley Julian, Shaw Therese and Cross Donna. “Bullying in School and Cyberspace: Associations with Depressive Symptoms in Swiss and Australian Adolescents.” Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Ment Heal 2(2010): 28-36.

Citation: Jegede, Temitope,Tunde-Ayinmode MF, Tolulope Jegede and Adesanmi Akinsulore, et al. “Bullying Behavior Roles and Mental Health Correlates Among Secondary School Students in Ilesa, Nigeria” J Child Adolesc Behav 9 (2021): 397

Copyright: © 2021 Jegede T, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Share This Article

Open Access Journals

Article Usage

- Total views: 1806

- [From(publication date): 0-2021 - Apr 02, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 1103

- PDF downloads: 703