Brief Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy for Methamphetamine Use among Methadone-Maintained Women: A Multicentre Randomised Controlled Trial

Received: 04-Aug-2016 / Accepted Date: 24-Aug-2016 / Published Date: 31-Aug-2016 DOI: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000294

Abstract

The article entitled “Brief Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy for Methamphetamine Use among Methadone-Maintained Women: A Multicentre Randomised Controlled Trial” has been accepted for publication in the Journal of Addiction Research & Therapy considering the statements provided in the article as personal opinion of the author which was found not having any conflict or biasness towards anything. As the article was a perspective one, information provided by the author was considered as an opinion to be expressed through publication. Publisher took decision to make the article online solely based on the reviewers suggestion which considered the article not but a personal opinion of the author. However, it is found that the author have some personal concerns and issues, therefore, being retracted from the journal.

Keywords: Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy, Methamphetamine Use

Introduction

Co-existing methamphetamine (MA) use disorder among methadone clients is a global health concern [1,2]. Amphetamine-Type Stimulants (ATS) including MA are the major illicit drugs used by over 20% of those in drug treatment in Asian countries, 12% in North American region and nine percent in the European region [1]. These statistics are concerning in light of poor treatment outcomes and high treatment costs [3,4].

MA use disorder is common as an important health problem among methadone-maintained women in Iran [5,6]. Among female methadone-maintained clients, MA use is associated with greater depression and dependence and lower treatment retention than men [1,2]. Therefore, it is critical to deliver MA treatment for this group before poor treatment outcomes occur.

To date, there is no any approved pharmacotherapy for MA use disorder [7]. Long-term psychosocial treatments such as the Matrix Model and contingency management are the main interventions [8,9]. These treatments are resource intensive and expensive [10]. Existing literature shows that such treatments have produced moderate effects in terms of either reducing or ceasing MA use. Furthermore, attrition rates are high [10].

In recent years, brief cognitive-behavioural therapy (BCBT) has been suggested as a new treatment for ATS use disorder. This is because BCBT has a strong potential to overcome operational barriers to implementation and suggests numerous advantages over existing psychosocial treatments [11]. BCBT aims to reduce or cease substance use and harms by enhancing client skills, motivation and commitment to change substance use behaviour [11]. BCBT offers increased feasibility compared with existing psychosocial treatments, requiring shorter training and less staff time for delivery. Second, BCBT consists of practical skills that can be implemented with high fidelity in drug treatment settings. Finally, the ability of BCBT to incorporate motivational enhancement therapy and CBT elements creates an interactive environment which can foster high client engagement [11,12].

BCBT was first devised for amphetamine use in Australia in 2001 [11]. In two randomised controlled trials in Australia, BCBT was found to be more effective than drug education in reducing regular amphetamine use, sustained at six-month follow-up [12,13]. Although these preliminary results are promising, an important next step is to evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of BCBT in the treatment of MA use disorder. Evaluation can also help determine the generalizability of BCBT to methadone treatment services [12,13]. As female methadonemaintained clients are more likely to suffer from the side effects of MA use disorder than men [14], the current study aimed to evaluate the effects of BCBT on a group of these women.

Methods

Design

A multicentre, randomised, controlled trial (RCT) was conducted in Tehran, Iran in 2014-2015. The study design included baseline assessments, four weeks of BCBT or standard drug information, and one 12 week follow-up. The study settings included four central methadone treatment clinics which were under the supervision of the Ministry of Health (MoH) and reported high rates of MA use among their clients to MoH. The study was approved by the University of New South Wales (HC13310) in Australia, Tehran University of Medical Sciences (92-04-49-25491) and the Iranian National Centre for Addiction Studies (25491). The study was registered with Iranian Clinical Trial Registry (2015-0914-24012-N1).

Participants and recruitment

Participants were women enrolled in methadone treatment at the study sites that were at least 18 years of age and reported regular MA use. Regular MA use was defined as at least weekly use (a score of 0.14 or more on the MA items of the Opiate Treatment Index (OT) [15]. Participants were also required to provide urine specimens and report a stable methadone dose for at least three months prior to recruitment. Additional concomitant substance use was not a reason for exclusion. Participants were excluded if they reported severe medical and/or psychiatric conditions or engagement with CBT within the past 12 months.

Potential participants were identified by the centre managers and were referred for screening. Participation was confidential and voluntary. Participant screening and enrolment were completed by a research coordinator (a graduate psychologist). Recruitment was completed between July 28-12 Oct 2014 and 14 Jan-15 May 2015. All recruited participants provided informed consent.

Randomisation, allocation concealment

Randomisation and allocation concealment were done based on a standard guide [16]. To account for randomisation and to detect a standardised between-group mean difference of 0.20 with 80% power (p=0.05) [17], 120 participants were required. This was done to detect the between group differences in outcome measures. Participants were randomly assigned (1:1) into one BCBT group (n=60) and one control group (n=60) using STATA-9 [18]. Blocked randomisation was used for group allocation by a research coordinator.

Research team

Two trained clinicians (doctoral-level psychologists) with at least eight years of experience in providing CBT provided the treatment and control sessions. Two researcher assessors (masters-level clinical psychologists) completed assessments at weeks 0 and 4 and 12. One nurse took urine specimens at weeks 0, 4 and one nurse too urine specimens at week 12.

Masking

The research team was masked to the participants’ group allocation and had no connections to the study sites. The study clinicians informed participants about group allocation and the importance of concealment. Other precautionary strategies included the clinicians and research assessors considering booking arrangements and room use and participants being reminded not to talk with other participants about treatment allocation or questionnaires. There was no case of an allocation being revealed to the research team.

Treatment and control guides

The BCBT guide of Baker and colleagues in Australia [11] was used to conduct the treatment sessions. The interactive role play sessions consisted of weekly individual one-hour motivational enhancement therapy and CBT for four weeks as well as daily homework assignments [19]. The control sessions consisted of weekly individual 1 h standard drug information [20].

Outcome measures

There were one primary outcome and eight secondary outcomes. For each outcome measure, it was hypothesised that the betweengroup difference was significant at week four and the results would remain significant at week 12. All of the outcome measures were assessed over the previous four weeks.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome included number of days of MA use assessed by the Timeline Follow Back (TLFB).The TLFB is an internationallyused calendar that measures days of drug use. The TLFB has high reliability and validity [21]. The reliability of the TLFB has been evaluated for illicit drug users in Iran and has been found high (a=0.86) [22].

Secondary outcome

The OTI was used to assess the quantity/frequency of MA use. Higher scores on the MA items indicate more frequent and higher dose MA use. A score of at least 0.14 is consistent with at least weekly use. The OTI has high reliability and validity [15]. The reliability of the OTI has been evaluated among illicit drug users in Iran and has been found to be high (a=0.85) [23].

Severity of MA dependence was assessed using the Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS). The SDS is a 5-item questionnaire and scores are in the range of 0-15. Higher scores indicate higher severity of MA use [24]. Because of no Persian version, the SDS was assessed for testretest reliability on 30 women in two-weeks which was found high (a=90).

Readiness to change MA use was assessed using the Contemplation Ladder (CL). The CL has a score range of 0-10. Higher scores on the CL indicate greater readiness to reduce MA use [25]. The reliability of CL has been evaluated in a study of illicit drug users in Iran and has been found high (a=92) [26].

Psychological well-being was assessed using the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28). Scores are in the range of 0-28. Higher scores indicate greater psychiatric distress. The questionnaire has high reliability and validity [27]. The reliability of the GHQ-28 has been evaluated for illicit drug users in Iran and has been found high (a=0.85) [28].

Other secondary outcomes included quantity/frequency of heroin use, quantity/frequency of benzodiazepine use, social functioning, HIV risk behaviours and criminality which were assessed using the OTI. Social functioning scores range between 0 and 48. Higher scores indicate better social functioning. The sub-scale of HIV risk behaviours measures drug injecting and sexual behaviours. In this study, only the subscale of sexual behaviours was used because of no reported drug injection; the score is between 0-25. The criminality score ranges between 0-16. Higher scores in these two subscales indicate greater risk behaviours and criminality [15].

Procedure

All study procedures were conducted at the study sites between 28 July 2014 and 15 September 2015. Following the completion of baseline assessments, four weeks of treatment and control sessions were conducted. The BCBT group was also given pamphlets to practice new learnt skills for two hours every day between sessions. If a homework assignment was left incomplete, it was completed in the next session.

The clinicians called participants by telephone between sessions to maintain treatment momentum. The chief investigator (Z. AM) supervised the research team weekly to monitor adherence to the study protocol. All participants received small gifts after completing the assessments. Furthermore, participants were asked to provide feedback about the sessions and homework assignments following the completion of the sessions. Those participants who were abstinent from MA use at weeks 4 and 12 were also asked to provide feedback bout the sessions and homework assignments at week 12.

Urine specimens were taken from all participants to detect MA use at week 0 and from those participants who reported no MA use at weeks 4 and 12. The specimens were stored in plastic urine cups and were sent immediately for laboratory analysis. This was done to double-check the likelihood of self-reported abstinence from MA use at weeks 4 and 12. Urine specimens were analysed in a laboratory using Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS).

Treatment sessions were audio-recorded and rated with participant agreement for adherence to the BCBT guide by two clinical psychologists. Control sessions were individually supervised by the same psychologists to assess adherence to the drug information materials. The rating of all sessions was based on a 0-6 Likert Scale which 0 indicated appropriate performance and six indicated high performance [29]. Psychologists were also asked to provide feedback about the fidelity assessment following the completion of rating.

Statistical analyses

Data analyses were done using the statistical software of Stata (version 13.1). Baseline equivalence between the groups was examined using Chi-square test for categorical variables, independent samples ttest and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous outcomes. To assess treatment effects on each outcome measure over time, Intention-To-Treat analysis and logistic Generalised Estimating Equations Regression Model were performed. These methods were selected for data analyses because they include all data in analysis and do not have the common limitations of Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance [30].

All analyses were adjusted for baseline scores on the outcomes. For continuous data, independent samples t-tests were performed. For other variables, Wilcoxon Rank-Sum tests were performed. Each variable was tested for normality using Shapiro-Wilk tests. Variables that were non-normal were analysed using Rank-Sum tests while normally distributed variables were analysed using t-tests.

To account for the treatment effects, Cohen’s effect size was calculated. An effect size of 0.3 indicates a small statistical effect while an effect size of 0.5 indicates a moderate statistical effect and an effect size of 0.8 or higher indicates a large statistical effect. A series of sensitivity analyses and multiple imputation models are recommended methods for handling missing data related to attrition in RCTs [31]. In this study, multiple imputation models were not feasible because of a low rate of attrition. Therefore, Little’s MCAR test was performed. Furthermore, sensitivity analyses were performed to examine the impacts of attrition on the outcome measures.

Results

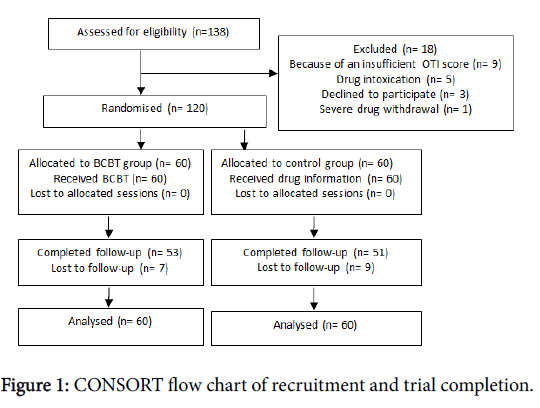

The flowchart related to the participants through each stage of the study is presented in Figure 1. All of the participants enrolled and consented into the study and completed either the BCBT or the control sessions.

Baseline equivalence

The baseline characteristics were similar between the two groups. No participant had a history of MA injecting drug use, all participants smoked MA. However, participants in the BCBT group were more likely to be separated (p<0.05) or report lifetime imprisonment (p<0.05) than the control group (Table 1).

| Characteristics | BCBT group, n=60 | Control group, n=60 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years | 39.1 (SD 9.9) (range: 21-70) | 38.5 (SD 7.9) (range: 20-60) | |

| Schooling | |||

| <12 years | 50 (83.3%) | 50 (83.3%) | |

| 12 years | 7 (11.7%) | 8 (13.3%) | |

| 13-16 years | 3 (5%) | 2 (3.3%) | |

| Partner status | |||

| Living with partner | 16 (26.7%) | 15 (25.0%) | |

| Never partnered | 5 (8.3%) | 14 (23.3%) | |

| Separated | 11 (18.3%) | 3 (5.0%) | 0.05* |

| Divorced | 28 (46.7%) | 28 (46.7%) | |

| Employment status | |||

| Home duties | 22 (36.7%) | 16 (22.7%) | |

| Jobless | 36 (6.0%) | 35 (85.3%) | |

| Paid employment | 2 (3.3%) | 9 (15.0%) | |

| Lifetime imprisonment | 16 (26.6%) | 9 (15.0%) | 0.05* |

| Duration of MA dependence (years) | 5.3 (SD 2.6) | 5.5 (SD 1.5) | |

| Heroin smoking, | 14 (23.3%) | 17 (28.3%) | |

| Benzodiazepine ingestion | 9 (15.0%) | 11 (18.3%) | |

| Mean methadone dose (mg)1 | 70.7 (SD 28.1) | 61.1 (SD 24.9) | |

| Mean range of methadone dose (mg)1 | 10-165 | 15-115 | |

| Duration of methadone treatment, month | 26 (SD 19.5) | 24 (SD 13.4) |

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of the participants, 1 Last three months.

Treatment effects

Primary outcome

As presented in Table 2, the two groups were almost similar at week 0. There were significant reductions in the mean number of days of MA use per week in the BCBT group (z=8.10, d=0.74, p<0.001) control group showed no significant reduction. This result remained significant at week 12 (z=8.49, d=0.78, p<0.001) (Table 2).

| Characteristics | OR (95% CI) group time*, mean (SD) or n (%) | test results | P value | Effect (d) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCBT group | Control group | ||||

| Days of MAˡ use per week* | |||||

| Baseline | 3·88 (3·50, 4·25) | 3·75 (3·50, 4·25) | - | - | - |

| Treatment | 1·50 (0·00, 2·00) | 3·00 (2·50, 3·50) | z=8·10 | 0·001 | 0.74 |

| Follow-up | 1·25 (0·00, 1·75) | 4·00 (3·75, 4·50) | z=8·49 | 0·001 | 0.78 |

| Quantity/frequency of MA use* | |||||

| Baseline | 1·00 (0·33, 2·00) | 0·94 (0·66, 1·27) | - | - | - |

| Treatment | 0·12 (0·00, 0·25) | 1·00 (0·64, 1·25) | z=7·79 | 0·001 | 0.71 |

| Follow-up | 0·11 (0·00, 0·25) | 1·00 (0·66, 1·33) | z=7·27 | 0·001 | 0.66 |

| Severity of MA dependence† | |||||

| Baseline | 9.98 (9.43,10.54) | 10.23 (9.65-10.82) | - | - | - |

| Treatment | 5.40 (4.62, 6.18) | 10.97 (10.28, 11.66) | t (118)=10.71 | 0.001 | 1.96 |

| Follow-up | 5.25 (4.47, 6.03) | 10.58 (10.30, 11.40) | t (118)=11.73 | 0.001 | 2.14 |

| Readiness to changeMA use * | |||||

| Baseline | 5·00 (4·00, 5·00) | 4·00 (3·00, 4·50) | - | - | - |

| Treatment | 8·00 (7·50, 10·00) | 4·00 (3·00, 5·00) | z=-9·31 | 0.001 | 0.85 |

| Follow-up | 8·00 (7·00, 10·00) | 4·00 (3·00, 4·00) | z=-8·96 | 0.001 | 0.82 |

| Psychological well-being† | |||||

| Baseline | 16.72 (15.66,17.77) | 16.28 (15.32,17.25) | - | - | - |

| Treatment | 8.52 (7.66,9.38) | 15.60 (14.82,16.38) | t(118)=12.20 | 0.001 | 2.23 |

| Follow-up | 10.27 (9.57,10.96) | 17.20 (16.44,17.96) | t(118)=13.50 | 0.001 | 2.47 |

| Social functioning* | |||||

| Baseline | 25.50 (21.50, 28.00) | 20.00 (18.00, 22.00) | - | - | - |

| Treatment | 25.00 (21.00, 28.50) | 19.50 (17.00, 21.00) | z=-5.87 | 0.001 | -0.54 |

| Follow-up | 25.50 (21.50, 28.00) | 20.00 (18.00, 21.00) | z=-6.30 | 0.001 | -0.58 |

| High risk sexual behaviours* | |||||

| Baseline | 4.00 (2.00,10.00) | 5.50 (4.00,10.00) | - | - | - |

| Treatment | 4.00 (2.00,9.00) | 5.00 (3.00,9,00) | z=1.36 | 0.173 | 0.12 |

| Follow-up | 5.00 (3.00,9.00) | 5.00 (3.50, 9.00) | z=0.78 | 0.433 | 0.07 |

| Criminality* | |||||

| Baseline | 0.00 (0.00,2.00) | 1.00 (0.00,2.00) | - | - | - |

| Treatment | 0.50 (0.00, 2.50) | 1.00 (0.00,2.00) | z=0.53 | 0.595 | 0.05 |

| Follow-up | 1.00 (0.00, 2.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00) | z=-1.43 | 0.153 | -0.13 |

Table 2: Treatment outcomes, ˡ MA=Methamphetamine; * Data not normally distributed: median and interquartile range presented and difference tested with Wilcoxon rank-sum test; † Data normally distributed: mean and 95% confidence interval are presented and difference tested with independent samples t-test.

Secondary outcomes

There was a significant reduction in the mean score of MA use on the OTI in the BCBT group at week 4 (z=7.79, d=0.71, p<0.001) which remained significant at week 12 (Table 2). Furthermore, the severity of MA dependence significantly declined in the BCBT group at week 4 (t (118)=10.71, d=1.96, p<0.001). There were also significant improvements in readiness to change MA use (z=-9.31, d=0.85, p<0.001), psychological well-being (t (118) =12.20, d=2.23, p<0.001) and social functioning in the BCBT group at week 4 (z=-5.87, d=-0.54, p<0.001). These results remained significant in the BCBT group at week 12. However, the control group showed no significant changes over the same time (Table 2).

No significant score differences in high risk sexual behaviours and criminality were detected between the two groups due to the small number of participants reporting these problems (Table 2). Furthermore, 31 participants reported heroin use at week 0. Overall, 24 and 21 participants in the two groups reported heroin use at weeks 4 and 12 respectively. Additionally, 20 participants reported benzodiazepine use at week 0. Overall, 16 and 12 participants reported benzodiazepine use at weeks 4 and 12 respectively. Due to the small numbers of heroin and benzodiazepine users, the score differences between the groups were zero in the statistical model which indicated no significant changes at weeks 0, 4 and 12. Therefore, data have not been shown in Table 2.

Urinalysis

Urine specimens were taken from those participants who reported no MA use (n=20) at weeks 4 and 12. All twenty participants reporting no MA use were in the BCBT group and nineteen of them (31.6% of the BCBT group) provided urine specimens at week 4 which were negative for MA. No participant in the control group reported abstinence from MA. Therefore, no urine specimen was collected. These results remained stable at week 12.

Attrition analyses

The overall attrition rate was low (i.e., 13.3%). All participants completed the treatment and week four assessments; and only seven participants (11.6%) in the BCBT group and nine participants (15%) in the control group were lost to follow-up. Attrition analyses were performed to determine whether participants that were lost to followup were different from others. The result of Little’s MCAR test was not significant (χ2 (23)=14.941, p=0.897). There were no significant associations between attrition and any of the other study outcomes.

Participant and psychologist feedback of the sessions

All participants in the BCBT group evaluated the treatment favourably, with over 71% indicating that the treatment including homework assignments was a feasible method to reduce MA craving and relapse and they planned to use the learnt skills in their own lives. Participants in the control group (n=60) evaluated the sessions favourably, with over 83% indicating that the sessions were enjoyable to them. The psychologists who did the fidelity assessments reported that all sessions were satisfactory (100%). They reported that 82% of the sessions were conducted with high quality and the remaining sessions (18%) were held at an acceptable level.

Participant evaluation of homework assignments

Overall, 39 participants (62%) completed homework assignments at home. They reported that homework assignments were needed to maintain the treatment effects. Twenty one participants (51%) completed homework assignments in sessions and they reported the same. Those participants who ceased MA use reported completing all homework assignments. All of them rated homework assignments as effective methods to maintain the treatment effects.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this RCT is among the few studies that have specifically evaluated the effects of BCBT in reducing MA use disorder in methadone treatment services. While MA use disorder is a current global health concern, there are few RCTs of effective psychological treatments for this problem [10]. Therefore, the present study makes a significant contribution to the literature by addressing recommendations to invest in MA use treatment [10,32].

Results of this RCT revealed that BCBT had significant treatment effects on some primary and secondary outcomes. In terms of MA use, BCBT had moderate treatment effects on reducing days and quantity/ frequency of MA use as well as significant treatment effects on readiness to change MA use. Furthermore, there were a substantial treatment effect with a considerable effect size on social functioning and strong treatment effects with large effect sizes on reducing severity of MA dependence and improving psychological well-being. These results reinforce the conclusion that the trial was sufficiently powered to detect treatment effects at reliable statistical levels. These findings are also consistent with the results of other similar RCTs in terms of both significance and magnitude of effects [12,13,32]. Importantly, the link between reduced psychostimulant use and improved measures in other domains such as psychiatric distress and social functioning has been recently supported by research studies [33]. It will be important to replicate this study to assess the magnitude and sustainability of these treatment effects over longer follow-up periods.

Part of the positive treatment effects can be related to the combination of BCBT with homework assignments. Participants reported that homework assignments as part of treatment were reliable methods to reduce MA use and relapse. In fact, participants in the BCBT group were engaged in learning the techniques related to MA refusal skills, relapse prevention and craving management on a daily basis. Therefore, homework assignments were likely to create great opportunities to generalise the learnt CBT skills in the treatment sessions to real-world situations. We found no similar study to compare this study result with. In particular, it will be important to assess whether the effects of homework assignments can be translated into behavioural changes in methadone treatment settings at later time points.

The link between reduced psychostimulant use and improved measures in concurrent heroin and benzodiazepine use, high risk behaviours and criminality has been supported by research evidence [12]. In these domains, numbers were too small to assess apart from sexual risk behaviour and criminality which showed no significant changes. This issue has been reported elsewhere [34], and may be related to the retention of participants on a stable methadone dose and the effectiveness of methadone treatment in reducing these problems.

Although the study aimed to assess the effects of BCBT on reducing MA use disorder, 19 participants became completely abstinent from MA use. This may be related to high motivations to change among successful participants, their enhanced engagement in the treatment procedure and their success in generalising the learnt CBT skills to real-world situations. This is particularly important given previous findings from a large RCT of 871 MA-dependents indicated that high client engagement and retention in CBT was associated with sustained abstinence from MA use disorder and providing negative urine specimens for MA use at 12 and 36 month follow-ups [35].

Strengths of the study include the rigorous design and the strong follow-up rates. The study not only provides important information about the efficacy of BCBT in reducing MA use disorder but also adds to the treatment science field, in which there is a current paucity of RCTs. The attrition rates were low in the two groups which primarily imply the internal validity of the study. A low attrition rate indicates high client engagement in the study procedure, reduced bias and increased generalizability of the results [32]. High retention in studies of psychostimulant users in methadone treatment and CBT has been demonstrated elsewhere [36]. This finding may suggest the high clinical utility of BCBT delivered through the methadone programme.

A further strength is fidelity data which indicate that the sessions was conducted well, primarily due to its feasible nature which ensured that core study components were retained within methadone treatment centres. This is important given the strong link between high quality implementation and study outcomes [37] and lends support to the feasibility of BCBT to deliver treatment. Furthermore, participant feedback confirmed that participants’ positive perception of the trial.

Results must be interpreted in the context of several limitations which warrant discussion. The study was limited to methadonemaintained women. Therefore, the findings may not necessarily be generalizable to other clinical populations and settings. Furthermore, the study was limited to one follow-up. This was related to no an adequate fund. Because of the high potential risk of MA relapse, 24 week and 36 week follow-ups are required to investigate the sustainability of the BCBT effects on participants. The other limitation is the use of self-report data which are subject to recall and social desirability bias. Nonetheless, self-report is a valid method for measuring illicit drug use [38]. In this study, assurances of confidentiality were provided and women voluntarily participated in the study, factors both of which have been indicated to enhance the accuracy of self-report [38].

Conclusion

In summary, we found that BCBT was feasible and efficacious for addressing co-existing MA use disorder and the associated harms among our methadone-maintained participants. Importantly, reduced severity of MA dependence and improved psychological health appeared to be more influenced by BCBT compared with other domains in this study. These findings may have important clinical implications for the treatment of MA use disorder among methadonemaintained women. The treatment of MA use disorder among methadone-maintained women may be facilitated by integrating BCBT into methadone treatment services. This issue should be investigated by conducting in future studies.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre (NDARC) in Australia.

Competing Interests

All authors have no competing interests.

Funding

The study was supported by a fund (HC13310) from NDARC through a postgraduate research scholarship to Z. AM in Australia.

References

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2010) World Drug Report. Vienna.

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2015) World Drug Report. Vienna.

- Amato L, Davoli M, Perucci CA, Ferri M, Faggiano F, et al (2005) An overview of systematic reviews of the effectiveness of opiate maintenance therapies: Available evidence to inform clinical practice and research. Subst Abuse Treat: 321-329.

- Haledon HJ, Stetler CB, Bangerter A, Noorbaloochi S, Stitzer ML, et al (2014) An implementation-focused process evaluation of an incentive intervention effectiveness trial in substance use disorders clinics at two Veterans Health Administration medical centers. Addict SciClinPract 9: 12.

- Shariatirad S, Maarefvand M, Ekhtiari H (2013) Methamphetamine use and methadone maintenance treatment: An emerging problem in the drug addiction treatment network in Iran. Int J Drug Policy 24: e115-116.

- Radfar R, Cousins SJ, Shariatirad S, Noroozi A, Rawson R (2016) Methamphetamine use among patients undergoing methadone maintenance treatment in Iran; a threat for harm reduction and treatment strategies: A qualitative study. Int J High Risk Behav:e30327.

- Phillips KA, Epstein DH, Preston KL (2014) Psychostimulant addiction treatment. Neuropharmacology 87: 150-160.

- Corsi KF, Garver-Apgar C, Booth RE (2015) Contingency management and case management for out-of-treatment methamphetamine users. Drug Alcohol Depend 146: e252.

- Repack CJ, Shoptaw S (2014) Development of an evidence-based, gay-specific cognitive behavioral therapy intervention for methamphetamine-abusing gay and bisexual men. Addict Behav 39:1286-1291.

- Lee NK, Rawson RA (2008) A systematic review of cognitive and behavioural therapies for methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Rev 27: 309-317.

- Baker A, Kay-Lambkin F, Lee NK, Claire M, Jenner LA (2003) Brief cognitive behavioral intervention for regular amphetamine users. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, Canberra.

- Baker A, Lee NK, Claire M, Lwin TJ, Grant T, et al. (2005) Brief cognitive behavioural interventions for regular amphetamine users: A step in the right direction. Addiction 100: 367-378.

- Baker A, Boggs TG, Lewin TJ (2001) Randomised controlled trial of brief cognitive-behavioural interventions among regular users of amphetamine. Addiction 96: 1279-1287.

- Evans E, Kelleghan A, Li L, Min J, Huang D, et al. (2015) Gender differences in mortality among treated opioid dependent patients. Drug Alcohol Depend 155: 228-235.

- Darke S, Hall W, Heather N, Ward J (1991) Development and validation of a multi-dimensional instrument for assessing outcome of treatment among opioid users: The Opiate Treatment Index. Brit J Addict 87: 593-602.

- Doig GS, Simpson F (2005) Randomization and allocation concealment: a practical guide for researchers. J Crit Care 20: 187-191.

- Ryan P (1997) Ralloc: Stata module to design randomised controlled trials. College Department of Economics, Boston.

- Humeniuk R, Edwards H, Robert A, Meena S (2010) Self-help strategies for cutting down or stopping substance use: A guide. World Health organisation, Geneva.

- National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre (2014) Fact sheets. University of New South Wales, Sydney.

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Buchan G, Cleland PA, Fedoroff I, et al (1996) The reliability of the timeline follow back method applied to drug, cigarette and cannabis use. The 30th annual meeting of the Association for Advancement of Behaviour Therapy, New York.

- Khademi MJ, Monirpoor N (2015) Validation of the timeline follow back among narcotics anonymous clients. J Kermanshah Uni Med Sci 19: 191-196.

- Azizi A, Borjali A, Golzari M (2010) The effectiveness of emotion regulation training and cognitive therapy on the emotional and addictional problems of substance abusers. Iran J Psychiatry 5: 60-65.

- Topp L, Mattick RP (1997) Choosing a cut-off on the severity of dependence scale (SDS) for amphetamine users. Addiction 92: 839-845.

- Biener L, Abrams DB (1991) The contemplation ladder: Validation of a measure of readiness to consider smoking cessation. Health Psychol 10: 360-365.

- Amini-Lari M, Joulaei H, Faramarz H (2016) Group cognitive-behavioural therapy for opiate use reduction in Shiraz: The first study from the Persian Gulf region of Iran. Int J High Risk Behavi Addict (in press).

- Makowska Z, Merecz D, Mościcka A, Kolasa W (2002) The validity of general health questionnaires, GHQ-12 and GHQ-28, in mental health studies of working people. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 15: 353-362.

- Khosravi A, Mousavi SA, Chaman R, Sepidar Kish M, Ashrafi E, et al (2015) Reliability and validity of the Persian version of the World Health Organization-five well-being index. Int J Health Sci 1: 17-19.

- James IA, Blackburn IM, Milne DL, Reichfelt FK (2001) Moderators of trainee therapists' competence in cognitive therapy. Br J ClinPsychol 40: 131-141.

- Gueorguieva R, Krystal JH (2004) Move over ANOVA: Progress in analysing repeated-measures data and its reflection in papers published in the Achieves of General Psychiatry. Ach Gen Psychiatr 61: 310-317.

- Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, et al. (2009) Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: Potential and pitfalls. BMJ 338: b2393.

- Tait RJ, McKetin R, Kay-Lambkin F, Carron-Arthur B, Bennett A, et al. (2014) A web-based intervention for users of amphetamine-type stimulants: 3month outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Ment Health 1: e1.

- Kiluk BD, Nich C, Witkiewitz K, Babuscio TA, Carroll KM (2014) What happens in treatment doesn’t stay in treatment: Cocaine abstinence during treatment is associated with fewer problems at follow-up. J Consult ClinPsychol 82: 619-627.

- McKetin R, Dunlop AJ, Holland RM, Sutherland RA, et al. (2013) Treatment outcomes for methamphetamine users receiving outpatient counselling from the stimulant treatment program in Australia. Drug and Alcohol Rev 32: 80-87.

- Rawson RA, Gonzales R, Greenwell L, Chalk M (2012) Process-of-care measures as predictors of client outcome among a methamphetamine-dependent sample at 12 and 36month follow-ups. J Psychoactive Drugs 44: 342-349.

- Nuijten M, Blanken P, van den Brink W, Hendriks V (2014) Treatment of crack-cocaine dependence with topiramate: A randomized controlled feasibility trial in The Netherlands. Drug Alcohol Depend 138: 177-184.

- Durlak J (2013) The importance of quality implementation for research, practice and policy (ASPE Research Brief). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Washington.

- Darke S (1998) Self-report among injecting drug users: A review. Drug Alcohol Depend 51: 253-263.

Citation: Alammehrjerdi Z, Ezard N, Clare P, Shakeri A, Babhadiashar N, et al. (2016) Brief Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy for Methamphetamine Use among Methadone-Maintained Women: A Multicentre Randomised Controlled Trial. J Addict Res Ther 7:294. DOI: 10.4172/2155-6105.1000294

Copyright: ©2016 Alammehrjerdi Z, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Select your language of interest to view the total content in your interested language

Share This Article

Recommended Journals

Open Access Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 6107

- [From(publication date): 0-2016 - Dec 09, 2025]

- Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views: 5105

- PDF downloads: 1002