Review Article Open Access

Bowel Imaging in IBD Patients: Review of the Literature and Current Recommendations

Lahat A1* and Fidder HH21Gastroenterology, Chaim Sheba Medical Center, Ramat Gan, Israel

2Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University Medical Center Utrecht, P.O. Box 85500, 3508 GA Utrecht, The Netherlands

- *Corresponding Author:

- Adi Lahat

Department of Gastroenterology

Chaim Sheba Medical Center Tel Hashomer, Israel

Tel: +972-3-5302660

Fax: +972-3-5303160

E-mail: zokadi@gmail.com

Received date: April 20, 2014; Accepted date: June 02, 2014; Published date: June 10, 2014

Citation: Lahat A, Fidder HH (2014) Bowel Imaging in IBD Patients: Review of the Literature and Current Recommendations. J Gastroint Dig Syst 4:189. doi:10.4172/2161-069X.1000189

Copyright: © 2014 Lahat A, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Gastrointestinal & Digestive System

Abstract

Imaging studies are essential in the diagnosis, treatment and follow up of IBD patients. The use of bowel imaging serves to confirm the diagnosis, assess disease extent and characteristics (inflammatory versus fibrostenotic) and complications. Accepted methods for bowel imaging in IBD patients are: CT enterography (CTE), MR enteropgaraphy (MRE), Abdominal ultrasound and capsule endoscopy. Each technique has its advantages and disadvantages. IBD patients have relatively high risk for colorectal cancer, small bowel cancer lymphomas and other malignancies. This risk is related to the chronic inflammatory process as well as to immunosuppressive therapy. Accumulating data shows that exposure to ionizing radiation elevates the risk for malignancy. Even exposure to relatively low doses of radiation as 50 mSv was shown to cause an increase in the occurrence of solid tumors, mainly colorectal cancer and urogenital malignancies. Individualized approach considering patients' symptoms, age, medical history, previous radiation exposure and malignancy risk as well as the local facilities and experience should guide physicians' decision regarding the preferred imaging modality.

Keywords

Bowel imaging; IBD; Crohn's disease; Ulcerative colitis

Bowel Imaging in Ibd Patients: Review of the Literature and Current Recommendations

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory disorder that may affect the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus. Inflammation is transmural, and therefore may be complicated by fistula and abscess formation, perforations and fibrotic strictures. Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a form of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) which affects only the colon, thus causing abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea and weight loss. Both diseases may cause significant morbidity and diminished life quality [1-6]. Disease behavior in IBD is characterized by periods of flare ups with active symptomatic disease and periods of disease remission [7].

The main goal though treating an IBD patient is to achieve rapidly a clinical remission and to maintain this remission steady for the long run. Other goals include prevention of disease progression, irreversible structural damage to internal organs, medical complications, hospitalizations and operations and to achieve and maintain a full quality of life. Achieving complete mucosal healing was shown to be in good correlation with long term favorable prognosis, and therefore serves as another treatment target [8].

Imaging studies are essential in the diagnosis, treatment and follow up of IBD patients. The use of bowel imaging serves to confirm the diagnosis, assess disease extent and characteristics (inflammatory versus fibrostenotic) and complications.

Bowel imaging serves both in emergency setup as well as in habitual disease follow up. In emergency cases bowel imaging is used to diagnose intra-abdominal complications as bowel perforation, fistulas or abscess. In routine usage specific bowel imaging serves as a sensitive tool for periodic follow up of patients with small bowel disease, and to assess disease and complications reaction to treatment. In these cases bowel imaging helps to monitor patients' treatment by assessing inflammation and chronic damage to the intestine. Findings in regular bowel imaging are essential during follow up of chronic patients and affect prominently on treatment strategy, medications choices and dosages and recommendations for surgical or endoscopic interventions.

Therefore, bowel imaging is now a major tool to determine treatment decisions in chronic IBD patients, and the average patient will probably undergo repeated bowel imaging throughout his disease course.

This review will focus on the main imaging modalities accepted throughout IBD treatment and follow up, their advantages and disadvantages, radiation exposure in IBD patient and a suggested approach towards IBD patients imaging.

Accepted Methods for Small Bowel Imaging

CTE-Computed Tomography Enterography

CTE enables imaging of all solid organs, the peritoneal cavity and retroperitoneum and the small intestine [9-13]. Tagging and expansion of small bowel loops is performed by ingestion of contrast material dissolved in water.

Small bowel tagging can be done positively (the bowel lumen is brighter than the surrounding tissues) using contrast material containing iodine dissolved in water. This technique can be used with and without IV contrast material [9].

Small bowel tagging may also be achieved by using negative contrast material dissolved in water. In this technique the bowel lumen is darker than the surrounding tissues. The contrast materials used are usually hyperosmolar non-absorbable carbohydrates as lactulose, manitol, etc.

Negative contrast materials have the advantage of improved imaging of the small bowel wall, thus allowing a better estimation of the damage to the bowel wall [9-13]. Negative contrast materials mandate IV contrast material injection.

CTE has many advantages, as well as some disadvantages.

The technique allows scanning of all organs in the abdomen and pelvis in a single examination, thus enabling an alternative diagnosis. CT devices are highly accessible, and many emergency departments have 24-hour access to CT. The examination is relatively inexpensive. It is rapidly performed (usually around 10 seconds for a scan), thus causing minimal inconvenience to the patient and can be performed with partial patient cooperation. Since CTE is wildly used, there are many experienced radiologists and technicians trained in performing and analyzing the examination.

The main disadvantage of the CTE is the radiation involved. The amount of radiation in a single examination is approximately 15 mSv, and accumulates with multiple examinations. Thus, as little as three abdominal CTs can reach an accumulative radiation dose that was shown to be carcinogenic (see below).

In addition, performing a double bowel assessment with positive followed by negative contrast material on the same examination is impossible. Therefore, less information about small bowel wall can be obtained as compared to Magnetic Resonance enteropgaraphy ( MRE). Small bowel peristalsis cannot be assessed, and there is relatively inconvenience to the patient during preparation (drinking liters of contrast material) [9-13].

Magnetic Resonance Enterography-MRE

MR enterography is an MRI scan dedicated to imaging of the small bowel. Since each MRI examination is specifically aimed at a specific part of the body, the examination does not evaluate other abdomen and pelvic organs [14-18]. Naturally, the MRE has its advantages as well as disadvantages.

The main advantage of this technique is it´s radiation free quality.

In addition, the examination sequences can be repeated in different techniques and different planes in order to achieve maximum information regarding small bowel wall and lumen, and high quality imaging of extra intestinal complications as abscesses and fistulas may be obtained. Performing double bowel estimation with positive, followed by negative, contrast material on the same examination is possible, and there is an optional imaging of small bowel peristalsis (functional examination).

Most of the disadvantages of MRE originate from the use of MRI device itself. The examination cannot be performed in patients with metal implantations or patients who suffer from claustrophobia. The duration of the examination is relatively long, and takes between 20-60 minutes until completion. Full patient´s cooperation is necessary throughout the examination- a major drawback in small children. Since the focus is on the small bowel, other extraintestinal pathologies might be missed. The examination is relatively expensive, and is not easily accessible worldwide. There is a relatively inconvenience to the patient during preparation (drinking liters of contrast material) [14-18].

Abdominal and Bowel Ultrasound (US)

Abdominal ultrasound enables imaging of specific intra-abdominal organs, as well as IBD specific complications as intra-abdominal abscess and fistulas. For enhanced imaging the usage of advanced ultrasound devices with high resolution and high frequency probes is mandatory [19].

The examination does not involve ionizing radiation, it is highly accessible, relatively inexpensive and therefore affordable worldwide, easy to perform and causes no inconvenience to the patient. However, the examination is operator dependent, and necessitates high skilled ultrasonographist for optimal bowel imaging. There is low resolution in obese patients and lower sensitivity and specificity for small bowel pathology as compared to CT and MRI (67-96% and 79-97%, respectively). The utility of the examination in assessing disease activity is disputed [20-25].

Video Capsule Endoscopy-VCE

Video capsule endoscopy enables endoscopic noninvasive imaging of the small bowel. The examination is performed using small capsule ingested by the patient. After ingestion, the capsule advances with peristalsis in the bowel lumen until excretion. While in the bowel lumen, the capsule transmits data to receptors attached to the patients' abdominal wall. The capsule endoscopy examination is the most sensitive method for assessing small bowel mucosa [26].

VCE has the highest sensitivity for small bowel mucosal imaging, involves no inconvenience to the patient and no ionizing radiation.

Nevertheless, the examination is relatively expensive, and is not easily accessible worldwide. It cannot be performed in emergency settings and takes a long time to achieve complete imaging of the small bowel (usually takes a few hours). The examination necessitates high skilled reader, and time from examination ending to definite results might be relatively long. Most important, there is a considerable risk of capsule entrapment in the bowel lumen in patients with bowel strictures. Therefore, patients with known bowel strictures are not candidates to this examination [26].

Small Bowel Follow Through

Small bowel follow through is an older technique for small bowel imaging. This modality involves ingestion of liquid barium followed by serial X-ray images.

This technique enables assessment of the bowel lumen and the existence of fistulas.

However, it is not suitable for assessment of extraintestinal abdominal organs or complications.

The amount of radiation in a single examination is between 3-6 mSv, and accumulates with multiple examinations [27]. However, due to its relatively lower diagnostic yield this technique is seldom used today in the setting of IBD.

Risk of Malignancy in IBD Patients

IBD patients have relatively high risk for colorectal cancer and small bowel cancer [28-30]. This high risk is related to the chronic inflammatory process in the bowel, as well as to immunosuppressive therapy. These patients have higher risk of lymphomas and other malignancies as well [31,32]. In the light of this high risk of developing malignant diseases it is highly important not to expose these patients to other risk factors for malignancy.

Damage from exposure to ionizing radiation is well-recognized. Studies conducted in atomic radiation survivors showed that acute or prolonged exposure to ionizing radiation elevates the risk for malignancy [33,34]. Moreover, even exposure to relatively low doses of radiation as 50 mSv was shown to cause an increase in the occurrence of solid tumors, mainly colorectal cancer and urogenital malignancies [35]. In this context, it is estimated that approximately 2% of the world's malignant morbidity is the result of radiation for medical diagnosis [36], and that one out of 1000 patients undergoing abdominal CT with radiation level of 10 mSv will develop malignant disease in his life course as a result of radiation exposure [37]. Exposure in young age elevates the risk, since the risk from radiation unit is age dependent [38,39]. Recent data from over 10 million people exposed to CT scans in childhood or adolescence showed overall increased cancer incidence of 24% for exposed compared to unexposed controls. The incidence rate ratio increased by 0.16 for each additional CT scan, and was greater after exposure at younger age. The absolute excess incidence rate for all cancers combined was 9.38 per 100,000 person years at risk [40].

In recent years the practice of small bowel imaging, mainly abdominal CT, in IBD patient increased in 400 folds and in 840% [41-44]. Chatu et al found in a meta-analysis that 8.8% of IBD patients and 11.1% of CD patients are exposed to ionizing radiation of 50 mSv or higher. Risk factor for high exposure were disease related operation (odds ratio 5.4) and steroid treatment (odds ratio 2.4) [44].

Recently published data assessing the impact of abdominal CT performed in the emergency department on IBD patients found that 49.3% of CD patients and 19.2% of UC patients examined in the department underwent an abdominal CT .Notably, CT findings caused a change in management in 80.6% of CD patients and 69% of UC patients [45].

In the light of all data written above, the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and the European ECCO (Crohn's and Colitis Organization) published guidelines recommending to minimize IBD patients exposure to ionizing radiation by using alternative bowel imaging methods as MRI and US [46,47].

Since bowel imaging is essential during disease course of all IBD patients, a reasonable approach for management will be to stratify patient's individual risk to radiation exposure. Thus, a young patient with severe disease that necessitates recurrent hospitalizations, immunosuppressive therapy and operations can be categorically classified as a high risk patient. On the other hand, an older patient with mild disease that does not require immunosuppressive therapy, hospitalizations or operations will be classified as a low risk patient. Patients undergoing evaluation for suspected IBD, when the diagnosis of IBD is not highly probable may also be included in the low risk category.

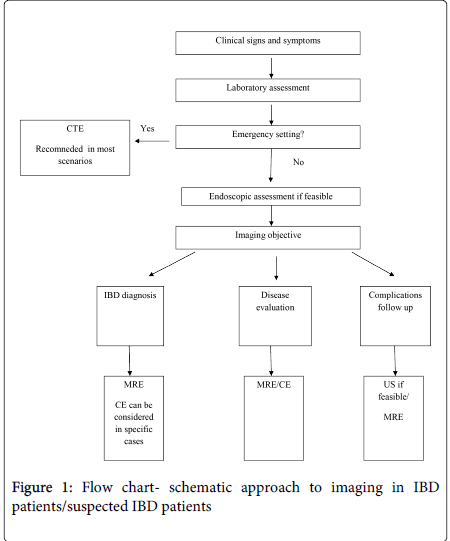

In high risk patients immense attention should be attributed towards minimizing the risk from radiation as much as possible. Therefore, MRE and US should always be considered in these patients as first line examination, depending on local facilities and experience. A schematic approach towards bowel imaging in IBD or suspected IBD patient (Figure 1).

In conclusion, small bowel imaging is one of the cornerstones throughout IBD diagnosis and treatment. High quality imaging is essential in order to establish the diagnosis, assess disease severity, extra intestinal manifestations and complications. Several imaging options exist, including CTE, MRE, US and VCE. Individualized approach considering patients' symptoms, age, medical history, previous radiation exposure and malignancy risk as well as the local facilities and experience should guide physicians' decision (Table 1).

| Radiation Dose, mSv | Major advantages | Major disadvantages | |

| CTE | 10-20 | Scanning all abdominal organs Accessible Rapid Relatively Inexpensive Experienced personnel |

High dose radiation IV contrast High volume contrast material Peristalsis not assessed |

| MRE | None | Radiation free High quality imaging of extraintestinal complications Multiplanar imaging capacity Imaging of small bowel peristalsis Good assessment of mucosal inflammation |

Not appropriate for claustrophobic and patients with metal implants Long examination time Expensive Limited accessibility High volume contrast material |

| Ultarsound | None | Radiation free Highly accessible Inexpensive Easy performed No patient inconvenience |

Operator dependant Lower sensitivity and specifity compared to CTE/MRE Low resolution in obese |

| CE | None | Radiation free Most sensitive for small bowel mucosa No patient inconvenience |

Potential risk of capsule entrapment Limited accessibility Expensive Sensitive only to small bowel mucosa Long examination time Not in emergency and in patients with bowel strictures |

| Small bowel follow through | 3-6 | Accessible Lower ionizing radiation than CTE Inexpensive |

Lower sensitivity for mucosal lesions than CTE/MRE Long examination time High volume contrast material Not suitable for diagnosis of extraintestinal pathologies Radiation |

Table 1: Imaging modalities- radiation doses and summery of advantages/disadvantages

References

- Love JR, Irvine EJ, Fedorak RN (1992) Quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. J ClinGastroenterol 14: 15-19.

- Casellas F, Arenas JI, Baudet JS, Fábregas S, García N, et al. (2005) Impairment of health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a Spanish multicenter study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 11: 488-496.

- Rubin GP, Hungin AP, Chinn DJ, Dwarakanath D (2004) Quality of life in patients with established inflammatory bowel disease: a UK general practice survey. Aliment PharmacolTher 19: 529-535.

- Casellas F, López-Vivancos J, Badia X, Vilaseca J, Malagelada JR (2001) Influence of inflammatory bowel disease on different dimensions of quality of life. Eur J GastroenterolHepatol 13: 567-572.

- Canavan C, Abrams KR, Hawthorne B, Drossman D, Mayberry JF (2006) Long-term prognosis in Crohn's disease: factors that affect quality of life. Aliment PharmacolTher 23: 377-385.

- Hjortswang H, Järnerot G, Curman B, Sandberg-Gertzén H, Tysk C, et al. (2003) The influence of demographic and disease-related factors on health-related quality of life in patients with ulcerative colitis. Eur J GastroenterolHepatol 15: 1011-1020.

- Latella G, Papi C (2012) Crucial steps in the natural history of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol 18: 3790-3799.

- Colombel JF, Rutgeerts PJ, Sandborn WJ, Yang M,Camez A, et al. (2014) Adalimumab induces deep remission in patients with Crohn's disease. ClinGastroenterolHepatol 12: 414-422.

- Macari M, Megibow AJ, Balthazar EJ (2007) A pattern approach to the abnormal small bowel: observations at MDCT and CT enterography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 188: 1344-1355.

- Bodily KD, Fletcher JG, Solem CA, Johnson CD, Fidler JL, et al. (2006) Crohn Disease: mural attenuation and thickness at contrast-enhanced CT Enterography--correlation with endoscopic and histologic findings of inflammation. Radiology 238: 505-516.

- Paulsen SR, Huprich JE, Fletcher JG, Booya F, Young BM, et al. (2006) CT enterography as a diagnostic tool in evaluating small bowel disorders: review of clinical experience with over 700 cases. Radiographics 26: 641-657.

- Booya F, Fletcher JG, Huprich JE, Barlow JM, Johnson CD, et al. (2006) Active Crohn disease: CT findings and interobserver agreement for enteric phase CT enterography. Radiology 241: 787-795.

- Arslan H, Etlik O, Kayan M, Harman M, Tuncer Y, et al. (2005) Peroral CT enterography with lactulose solution: preliminary observations. AJR Am J Roentgenol 185: 1173-1179.

- Gourtsoyiannis N, Papanikolaou N, Grammatikakis J(2001)Enteroclysis protocol optimization: comparison between 3D FLASH with fat saturation after intravenous gadolinium injection and true FISP sequences. EurRadiol 11: 908-913.

- Maccioni F, Viscido A, Broglia L, Marrollo M, Masciangelo R, et al. (2000) Evaluation of Crohn disease activity with magnetic resonance imaging. Abdom Imaging 25: 219-228.

- Low RN, Sebrechts CP, Politoske DA, Bennett MT, Flores S, et al. (2002) Crohn disease with endoscopic correlation: single-shot fast spin-echo and gadolinium-enhanced fat-suppressed spoiled gradient-echo MR imaging. Radiology 222: 652-660.

- Wiarda BM, Kuipers EJ, Heitbrink MA, van Oijen A, Stoker J (2006) MR Enteroclysis of inflammatory small-bowel diseases. AJR Am J Roentgenol 187: 522-531.

- Leyendecker JR, Bloomfeld RS, DiSantis DJ, Waters GS, Mott R, et al. (2009) MR enterography in the management of patients with Crohn disease. Radiographics 29: 1827-1846.

- Ledermann HP, Börner N, Strunk H, Bongartz G, Zollikofer C, et al. (2000) Bowel wall thickening on transabdominalsonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 174: 107-117.

- Hata J, Haruma K, Suenaga K, Yoshihara M, Yamamoto G, et al. (1992) Ultrasonographic assessment of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 87: 443-447.

- Sonnenberg A, Erckenbrecht J, Peter P, Niederau C (1982) Detection of Crohn's disease by ultrasound. Gastroenterology 83: 430-434.

- Lim JH, Ko YT, Lee DH, Lim JW, Kim TH (1994) Sonography of inflammatory bowel disease: findings and value in differential diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 163: 343-347.

- Worlicek H, Lutz H, Heyder N, Matek W (1987) Ultrasound findings in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: a prospective study. J Clin Ultrasound 15: 153-163.

- Pradel JA, David XR, Taourel P, Djafari M, Veyrac M, et al. (1997) Sonographic assessment of the normal and abnormal bowel wall in nondiverticular ileitis and colitis. Abdom Imaging 22: 167-172.

- Maconi G, Parente F, Bollani S, Cesana B, Bianchi Porro G (1996) Abdominal ultrasound in the assessment of extent and activity of Crohn's disease: clinical significance and implication of bowel wall thickening. Am J Gastroenterol 91: 1604-1609.

- Bourreille A, Ignjatovic A, Aabakken L, Loftus EV Jr, Eliakim R, et al. (2009) Role of small-bowel endoscopy in the management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: an international OMED-ECCO consensus. Endoscopy 41: 618-637.

- Mettler FA Jr, Huda W, Yoshizumi TT, Mahesh M (2008) Effective doses in radiology and diagnostic nuclear medicine: a catalog. Radiology 248: 254-263.

- Jess T, Gamborg M, Matzen P, Munkholm P, Sørensen TI (2005) Increased risk of intestinal cancer in Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Am J Gastroenterol 100: 2724-2729.

- Loftus EV Jr (2006) Epidemiology and risk factors for colorectal dysplasia and cancer in ulcerative colitis. GastroenterolClin North Am 35: 517-531.

- Persson PG, Karlén P, Bernell O, Leijonmarck CE, Broström O, et al. (1994) Crohn's disease and cancer: a population-based cohort study. Gastroenterology 107: 1675-1679.

- Bongartz T, Sutton AJ, Sweeting MJ, Buchan I, Matteson EL, Montori V. Anti-TNF antibody therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of serious infections and malignancies: systematic review and meta-analysis of rare harmful effects in randomized controlled trials. JAMA2006; 295: 2275–85.

- Kandiel A, Fraser AG, Korelitz BI, Brensinger C, Lewis JD (2005) Increased risk of lymphoma among inflammatory bowel disease patients treated with azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine. Gut 54: 1121-1125.

- Cardis E, Vrijheid M, Blettner M (2007) The 15-Country Collaborative Study of cancer risk among radiation workers in the nuclear industry: estimates of radiation-related cancer risks. Radiat Res167: 396-416.

- Vrijheid M, Cardis E, Blettner M, et al. The 15-Country Collaborative Study of cancer risk among radiation workers in the nuclear industry: design, epidemiological methods and descriptive results. Radiat Res 167: 361-379.

- Brenner DJ, Doll R, Goodhead DT, Hall EJ, Land CE, et al. (2003) Cancer risks attributable to low doses of ionizing radiation: assessing what we really know. ProcNatlAcadSci U S A 100: 13761-13766.

- Berrington de González A, Darby S (2004) Risk of cancer from diagnostic X-rays: estimates for the UK and 14 other countries. Lancet 363: 345-351.

- BEIR VII- Phase 2. Health risks from exposure to low levels of ionizing radiation. National academies Press, 2005. Available at:http://www.nap.edu/catalog/11340.html

- Brenner DJ, Hall EJ (2007) Computed tomography–an increasing source of radiation exposure.NEngl J Med 357: 2277-2284.

- Hall EJ, Brenner DJ (2008) Cancer risks from diagnostic radiology. Br J Radiol 81: 362-378.

- Mathews JD, Forsythe AV, Brady Z, Butler MW, Goergen SK, et al. (2013) Cancer risk in 680,000 people exposed to computed tomography scans in childhood or adolescence: data linkage study of 11 million Australians.BMJ 21: 346-360

- Kroeker KI, Lam S, Birchall I, Fedorak RN (2011) Patients with IBD are exposed to high levels of ionizing radiation through CT scan diagnostic imaging: a five-year study. J ClinGastroenterol 45: 34-39.

- Desmond AN, O'Regan K, Curran C, McWilliams S, Fitzgerald T, et al. (2008) Crohn's disease: factors associated with exposure to high levels of diagnostic radiation. Gut 57: 1524-1529.

- Peloquin JM, Pardi DS, Sandborn WJ, Fletcher JG, McCollough CH, et al. (2008) Diagnostic ionizing radiation exposure in a population-based cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 103: 2015-2022.

- Chatu S, Subramanian V, Pollok RC (2012) Meta-analysis: diagnostic medical radiation exposure in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment PharmacolTher 35: 529-539.

- Israeli E, Ying S, Henderson B, Mottola J, Strome T, et al. (2013) The impact of abdominal computed tomography in a tertiary referral centre emergency department on the management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment PharmacolTher 38: 513-521.

- Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, Ahmad T, Arnott I, et al. (2011) Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 60: 571-607.

- Van Assche G, Dignass A, Panes J, Beaugerie L, Karagiannis J, et al. (2010) The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease: Definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis 4: 7-27.

Relevant Topics

- Constipation

- Digestive Enzymes

- Endoscopy

- Epigastric Pain

- Gall Bladder

- Gastric Cancer

- Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- Gastrointestinal Hormones

- Gastrointestinal Infections

- Gastrointestinal Inflammation

- Gastrointestinal Pathology

- Gastrointestinal Pharmacology

- Gastrointestinal Radiology

- Gastrointestinal Surgery

- Gastrointestinal Tuberculosis

- GIST Sarcoma

- Intestinal Blockage

- Pancreas

- Salivary Glands

- Stomach Bloating

- Stomach Cramps

- Stomach Disorders

- Stomach Ulcer

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 15900

- [From(publication date):

June-2014 - Jul 12, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 11249

- PDF downloads : 4651