Review Article Open Access

Body Mass Index and the Risk of Gallbladder Cancer: An Updated Meta-analysis of Epidemiologic Studies

Canfeng Cai1, Bing Zeng1,2, Yuanfeng Gong3, Guoxing Chen1, Xiang Chen1, Wendong Huang1, Min Liang4, Jun Zeng1 and Chaoming Tang1*1Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, Qingyuan People’s Hospital, The sixth affiliated hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangdong 511518, China

2Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510120, China

3Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, Cancer Center of Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou 510120, China

4Department of Operating Room and Anesthesia, Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510120, China

- *Corresponding Author:

- Chaoming Tang

Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery

Qingyuan People's Hospital and The fifth affiliated hospital of Jinan University

Guangdong 511518, China

Tel: +86 13450366467

E-mail: chaomingtt001@163.com

Received date: May 29, 2015 Accepted date: June 30, 2015 Published date: July 06, 2015

Citation: Cai C, Zeng B, Gong Y, Chen G, Chen X, et al. (2015) Body Mass Index and the Risk of Gallbladder Cancer: An Updated Metaanalysis of Epidemiologic Studies. J Gastrointest Dig Sys 5:306. doi:10.4172/2161-069X.1000306

Copyright: © 2015 Cai C, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Visit for more related articles at Journal of Gastrointestinal & Digestive System

Abstract

Objectives: To provide a quantitative assessment of the association between excess bodyweight, expressed as increased body-mass index (BMI), and the risk of gallbladder cancer (GBC), we conducted an updated metaanalysis of epidemiologic studies. Methods: We searched the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases form1966 to February 2013, and the reference lists of retrieved articles. A random-effects model was used to combine study-specific results. A total of 12 cohort studies (involving 5,101 cases) and 8 case-control studies (1,013 cases and 43,591 controls) were included in the meta-analysis. Results: Overall, compared with normal weight, the summary relative risks of GBC were 1.14 (95% CI, 1.04-1.25) for overweight populations (BMI 25-30 kg/m2) and 1.56 (95% CI, 1.41-1.73) for obese (BMI >30 kg/m2) ones. Obese women had a higher risk of GBC than men did (women: RR 1.67, 95% CI 1.38-2.02, men: RR 1.42, 95% CI 1.21-1.66), and there was a significant association between overweight and GBC risk for women (RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.13-1.40), but not for men (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.94-1.20). In addition, subgroup analyses revealed that overweight people with smoking or alcohol consumption or in western countries were strongly associated GBC risk (RR 1.16, 95% CI 1.02-1.31 for smokers, RR 1.27, 95% CI 1.10-1.47 for drinkers, and RR 1.14, 95% CI 1.05-1.25). Conclusions: Findings from this meta-analysis indicate that obesity is associated with an increased risk of GBC in both men and women, and overweight is associated with GBC risk only in women.

Abstract

Objectives: To provide a quantitative assessment of the association between excess bodyweight, expressed as increased body-mass index (BMI), and the risk of gallbladder cancer (GBC), we conducted an updated meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies.

Methods: We searched the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases form1966 to February 2013, and the reference lists of retrieved articles. A random-effects model was used to combine study-specific results. A total of 12 cohort studies (involving 5,101 cases) and 8 case-control studies (1,013 cases and 43,591 controls) were included in the meta-analysis.

Results: Overall, compared with normal weight, the summary relative risks of GBC were 1.14 (95% CI, 1.04-1.25) for overweight populations (BMI 25-30 kg/m2) and 1.56 (95% CI, 1.41-1.73) for obese (BMI >30 kg/m2) ones. Obese women had a higher risk of GBC than men did (women: RR 1.67, 95% CI 1.38-2.02, men: RR 1.42, 95% CI 1.21-1.66), and there was a significant association between overweight and GBC risk for women (RR 1.26, 95% CI 1.13-1.40), but not for men (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.94-1.20). In addition, subgroup analyses revealed that overweight people with smoking or alcohol consumption or in western countries were strongly associated GBC risk (RR 1.16, 95% CI 1.02-1.31 for smokers, RR 1.27, 95% CI 1.10-1.47 for drinkers, and RR 1.14, 95% CI 1.05-1.25).

Conclusions: Findings from this meta-analysis indicate that obesity is associated with an increased risk of GBC in both men and women, and overweight is associated with GBC risk only in women.

Keywords:

Gallbladder cancer; Body mass index; Overweight; Obesity; Meta-analysis

Abbreviations:

GBC: Gallbladder Cancer; OR: Odds Ratio; RR: Relative Risk; HR: Hazard Ratio; SIR: Standardized Incidence Ratio; CI: Confidence Intervals; BMI: Body Mass Index

Introduction

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is a highly fatal malignancy that differs from other cancers of the biliary tract, as being about two to five times more common in women than in men [1]. Prognosis of GBC remains very poor due to its late clinical presentation, lack of effective non-operative therapy, and rapid turnover [2].

It has been established that history of gallstones is the leading cause of gallbladder cancer worldwide [3]. Additionally, genetic susceptibility, lifestyle factors, smoking, alcohol use and diabetes mellitus (DM) also increase the risk of GBC development [4-7]. Excess bodyweight, people who are overweight (BMI 25-30 kg/m2) or obese (BMI >30 kg/m2), is increasingly recognized as an important risk factor for various cancer types, including GBC [8]. A recent meta-analysis showed increased GBC risks of 15% for overweight people and of 66% for obese ones compared to those in normal weight [9]. However, this meta-analysis did not allow for some potential confounders, in particular smoking and alcohol abuse. Since then, lots of studies on the association between BMI and GBC risk have been published.

The aim of this meta-analysis was to update and expand the previous meta-analysis including all observational studies on this issue published through February 2015. Furthermore, we evaluated whether the risk of GBC varied between sex and geographic region.

Methods

Search strategies

We searched the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases for relevant studies that were published from 1966 to February 2015, using the search terms ‘body mass index’, ‘BMI’, ‘overweight’, ‘obesity’ or ‘excess body weight’, combined with ‘gallbladder cancer’, ‘gallbladder neoplasm’ or ‘biliary tract cancer’. We also reviewed the reference lists of retrieved articles to search for additional studies. No language restrictions were imposed.

Study selection criteria

A published article was included according to the following criteria: (1) cohort or case-control study in which GBC incidence or mortality was an outcome; (2) the exposure of interest was overweight or obesity defined by BMI; (3) estimates of relative risk (rate ratio, odds ratio, or standardized incidence ratio) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (or information to calculate them) of GBC associated with BMI or obesity. When there were multiple published reports from the same study population, only the one with the largest sample size was included in the meta-analysis. We excluded studies that did not provide risk estimates, only provided an RR with corresponding 95% CI per unit increase in BMI.

Data extraction

Three authors (C.C.F, B.Z, and J.Z.) independently evaluated all of the studies retrieved according to the pre-specified selection criteria. Discrepancies between the three reviewers were solved by discussion. The following information from each included study was extracted: the first author’s name, country of origin, publication year, sample size, study population, study design, sex and age of participants, duration of follow-up (cohort studies), BMI categories, method of assessment of weight and height (measured versus self-reported), and point estimates [relative risk (RR), odds ratio (OR), or standardized incidence ratio (SIR)] and corresponding 95% CI. When several risk estimates were presented, we used the ones adjusted for the largest number of potential confounders. We used the Newcastle-Ottawa scale to assess the quality of included studies [10].

Statistical analysis

The present systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the methodology recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration. Three authors (C.C.F, B.Z, and J.Z.) performed data analysis. To examine associations of overweight and obesity with the risk of GBC, we combined the log-RRs from each study for the category representing overweight (BMI 25-30 kg/m2) or obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2 or a discharge diagnosis of obesity) versus the reference category (BMI 18.5-24.9 kg/m2). If studies reported results separately for men and women, we combined the sex-specific estimates to generate an estimate for both genders combined. When non-standard BMI categories were used, we selected the category that was most similar to those defined by the WHO. The DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model was employed to combine the study-specific relative risks [11]. Subgroup analyses were carried out based on the study design (cohort and case-control studies), sex (men and women), and geographic region (non-Asia and Asia), body size assessment (measured and self-reported), Follow-up time (>10 years and <10 years), smoking status (smokers and non-smokers), Alcohol intake (Yes and No). We also conducted a sensitivity analysis in which one study was removed and the rest were analyzed to assess whether the results were affected statistically significantly.

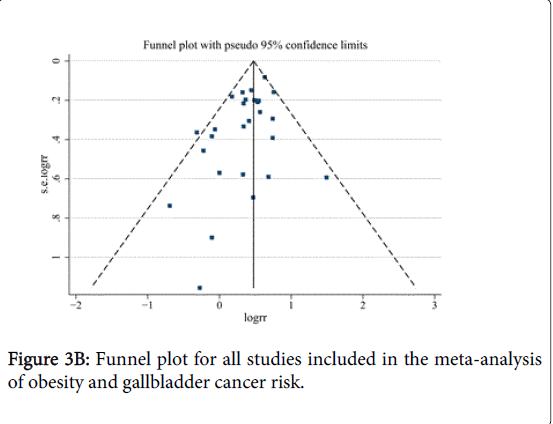

Heterogeneity among studies was assessed by using the Q and I2 statistics [12]. For the Q statistic, statistical significance was set at P<0.1. Publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots and the Egger test [13]. P<0.1 was considered to indicate statistically significant publication bias. In the presence of publication bias, we used the “trim and fill” method to correct such bias [14]. Meta-analyses were carried out using STATA12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Search results and study characteristics

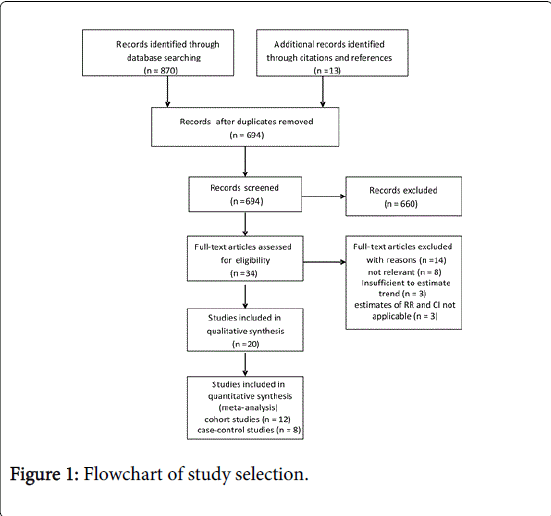

A total of 883 articles were identified through the literature search. Of these, 34 publications were potentially relevant for inclusion in the meta-analysis. Three studies were excluded because of gallbladder cancer was not distinguish from extrahepatic bile duct system cancer, 8 studies were not associated with GBC risk, and 3 studies were insufficient to estimate trend. Finally, a total of 12 cohort studies [15-26] (involving 5,101 cases) and 8 case-control studies [27-34] (1,013 cases and 43,591 controls) with data on BMI and/or obesity in relation to incidence of GBC were included in the meta-analysis (Figure 1). The main characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis are summarized in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

| Overweight | Obesity | |||||||||

| Studies, n | RR (95%CI) | Ph | Q | I2,% | Studies, n | RR (95%CI) | Ph | Q | I2,% | |

| Study design | ||||||||||

| Cohort studies | 12 | 1.15 (1.02-1.29) | 0.04 | 22.03 | 45.5 | 12 | 1.62 (1.45-1.81) | 0.28 | 19.98 | 14.9 |

| Case-control studies | 8 | 1.16 (0.96-1.41) | 0.68 | 5.75 | 0 | 8 | 1.37 (1.10-1.71) | 0.39 | 9.52 | 5.5 |

| Follow-up time | ||||||||||

| >10 years | 6 | 1.12 (1.00-1.27) | 0.04 | 17.78 | 49.4 | 9 | 1.65 (1.49-1.83) | 0.4 | 13.58 | 4.3 |

| <10 years | 2 | 1.52 (1.06-2.19) | 0.54 | 1.22 | 0 | 3 | 1.69 (0.91-3.17) | 0.1 | 6.32 | 52.5 |

| Control source | ||||||||||

| 3 | 1.14 (0.61-2.03) | 0.3 | 2.39 | 16.4 | 4 | 1.07 (0.66-1.74) | 0.57 | 2.03 | 0 | |

| Population | 4 | 1.18 (0.96-1.46) | 0.67 | 3.19 | 0 | 4 | 1.43 (1.09-1.89) | 0.3 | 6.12 | 18.3 |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Men | 9 | 1.06 (0.94-1.20) | 0.24 | 10.33 | 22.5 | 11 | 1.42 (1.21-1.66) | 0.85 | 5.63 | 0 |

| Women | 8 | 1.26 (1.13-1.40) | 0.45 | 6.84 | 0 | 10 | 1.67 (1.38-2.02) | 0.06 | 16.38 | 45 |

| Geographic region | ||||||||||

| Asia | 6 | 1.19 (0.98-1.45) | 0.06 | 15 | 46.7 | 7 | 1.48 (1.26-1.74) | 0.43 | 8.07 | 0.9 |

| Non-Asia | 9 | 1.14 (1.05-1.25) | 0.43 | 12.2 | 1.7 | 13 | 1.58 (1.40-1.80) | 0.22 | 22.38 | 19.6 |

| BMI ascertainment | ||||||||||

| Self-reported | 7 | 1.18 (1.01-1.36) | 0.46 | 9.74 | 0 | 7 | 1.65 (1.32-2.05) | 0.2 | 12.16 | 26 |

| Measured | 7 | 1.14 (1.01-1.30) | 0.04 | 17.4 | 48.3 | 8 | 1.51 (1.29-1.77) | 0.2 | 13.52 | 26.1 |

| Adjustment for confounders Smoking | ||||||||||

| Yes | 10 | 1.16 (1.02-1.31) | 0.16 | 20.42 | 26.5 | 11 | 1.55 (1.31-1.83) | 0.21 | 19.06 | 21.3 |

| No | 5 | 1.14 (0.98-1.32) | 0.21 | 7.1 | 29.5 | 9 | 1.59 (1.40-1.80) | 0.32 | 12.61 | 12.8 |

| Alcohol intake | ||||||||||

| Yes | 7 | 1.27 (1.10-1.47) | 0.37 | 10.87 | 8 | 7 | 1.64 (1.31-2.07) | 0.15 | 13.31 | 32.4 |

| No | 8 | 1.08 (0.98-1.19) | 0.25 | 12.59 | 20.6 | 13 | 1.56 (1.40-1.73) | 0.36 | 18.44 | 7.8 |

| RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; Ph, p value for heterogeneity | ||||||||||

Table 1: Stratified meta-analyses of overweight and obesity and risk of gallbladder cancer.

Quantitative data synthesis

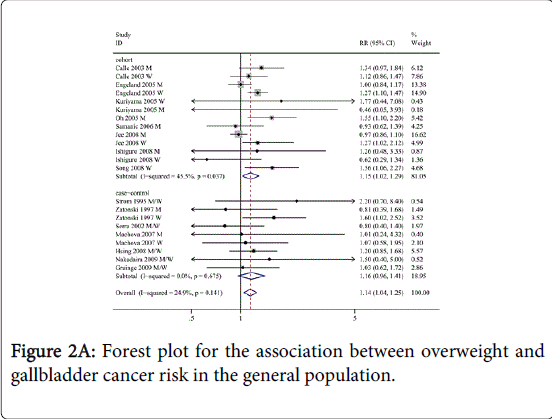

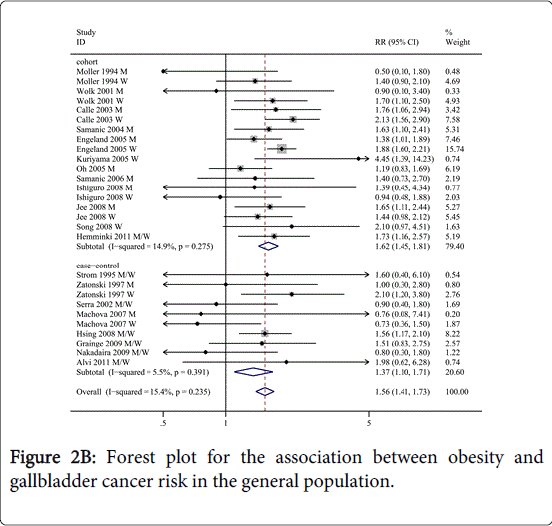

As shown in Figures 2A and 2B, the overall analysis of all studies revealed a statistically significant positive association between BMI and GBC risk (overweight: RR=1.14, 95% CI=1.04-1.25, I2=24.9%; obesity: RR=1.56, 95% CI=1.41-1.73, I2=15.4%) compared to normal weight. We then conducted subgroup meta-analyses by study design, sex, geographic region, ascertainment of exposure and confounders, as shown in Table 1.

For study design, a statistically significant positive link between BMI and GBC risk was observed for the cohort studies (overweight: RR=1.15, 95% CI=1.02-1.29, I2=45.5%; obesity: RR=1.62, 95% CI=1.45-1.81, I2=14.9%). Moreover, for cohort studies follow-up time >10 years, overweight and obesity were strongly associated with GBC incidence (overweight: RR=1.12, 95% CI=1.00-1.27, I2=49.4%; obesity: RR=1.65, 95% CI=1.49-1.83, I2=4.3%); while only overweight was observed associated with GBC risk for cohort studies that follow-up time < 10 years (RR=1.52, 95% CI=1.06-2.19, I2=0%). For the case-control studies, only obesity was strongly associated with GBC risk (RR=1.37, 95% CI=1.10-1.71, I2=5.5%). The summary RR of GBC incidence for obesity of population-based case-control studies was (RR=1.43, 95% CI=1.09-1.89, I2=18.3%); no link between obesity and GBC risk was observed in hospital-based case-control studies.

Interestingly, a significant sex-based difference was observed in the association between obesity and GBC risk, women with obesity had a higher risk of GBC development (RR=1.67, 95% CI=1.38-2.02, n=10 for women versus RR=1.42, 95% CI=1.21-1.66, n=11 for men; Pd=0.00). However, in men, overweight is not associated with risk of GBC (RR=1.06, 95% CI=0.94-1.20, I2 =22.5).

When stratified by geographic region, the association between obesity and the risk of GBC was similar for both Asia and non-Asia. For non-Asians, overweight was strongly associated with GBC incidence (RR=1.14, 95% CI=1.05-1.25, I2=1.7%); no link between overweight and the GBC risk was observed for Asians.

For self-report studies, both overweight and obesity had a higher risk of GBC development, while the summary RR did not differ appreciably between studies that based on direct measurements of weight and height.

In addition, when stratified by potential confounders, overweight people with smoking and alcohol consumption were strongly associated GBC risk, but not that of non-smokers and non-alcohol users(non-smokers: RR=1.14, 95% CI=0.98-1.32, I2=29.5%; non-alcohol users; RR=1.08 95% CI=0.98-1.19, I2=20.6%), indicating that smoking and alcohol use are positive confounders of the association between overweight and GBC. Interestingly, no differences were observed in the association between obesity and GBC incidence when stratified by smoking and alcohol use.

Sensitivity analyses and publication bias

In the sensitivity analyses, we removed one study at a time and calculating the summary RR. We found that there were no changes in the direction of effect when any one study was excluded, supporting the robustness of our results. For example, when the study of Engeland et al. was excluded (which seemed to have a strong influence on the meta-analysis estimate of effect), the summary RR remained similarly with the overall pooled RRs (RR=1.15, 95% CI=1.03-1.28, I2=17.8%).

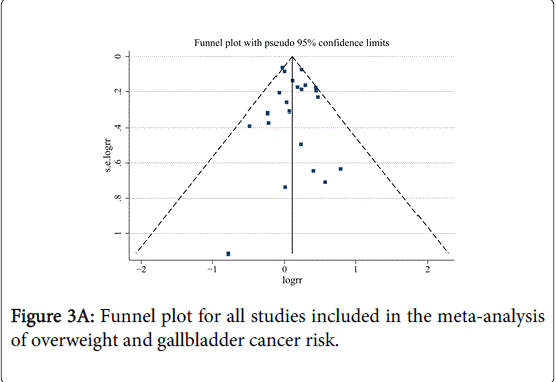

No indication of publication bias was observed in the literature on BMI and GBC risk in overweight group based on the Egger’s test (P=0.483) results (Figures 3A and 3B). For BMI and GBC risk in the obesity group, the funnel plot showed some asymmetry (Figure 3B), indicating some evidence of bias. However, when the “trim and fill” approach was performed, data were unchanged, suggesting that the effect of publication bias could be negligible.

Discussion

In this meta-analysis, we found that overweight and obesity were associated with 14% and 56% increased risk of GBC, respectively. Our results consist with previous studies that the association between obesity and GBC risk was higher in women than in men. Women with overweight had a higher risk of GBC development, no link between overweight and the GBC risk was observed for men. In addition, subgroup analysis showed that overweight was not associated with an increased risk of GBC in Asia, non-smokers and non-drinkers.

The mechanisms underlying the association between excess body weight and increased risk of GBC remain largely unknown. Obese always accompany with metabolic syndrome, a state of metabolic syndrome characterized by insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemias, and hypertension [35]. In obesity adults, alterations occur in the circulating levels of insulin, insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1, adi¬pokines, inflammatory factors, and pro-inflammatory cytokines. These mediators associated with the obese contribute to cancer-related processes, including growth signaling, inflam¬mation, and vascular alterations [36]. Further more, obese and metabolic syndrome are risk factors for gallstone disease [37], which may indirectly increase the risk for GBC [38]. In addition, female sex hormones adversely influence hepatic bile secretion and gallbladder function [39]. Estrogens increase cholesterol secretion and diminish bile salt secretion, while progestins act by reducing bile salt secretion and impairing gallbladder emptying leading to stasis [40]. These may partially explain the stronger association observed with overweight or obesity in women than in men.

To our knowledge, the strengths of this study include as follows: (1) this study was based on 20 epidemiologic studies, which might minimize the possibility of selection bias. (2) The large number of studies of different geographic region expands prior observational studies by permitting additional evaluation of subgroups, which may lend us to more precisely evaluate. (3) The association between BMI and GBC risk of each study were derived from regression after adjustment at least for age, and most adjusted for potential confounders for GBC, such as smoking and alcohol use.

As with any meta-analysis of observational studies, our study also has limitations. First, inadequate control for confounders may bias the results, leading to exaggeration or underestimation of risk estimates. Thus, when interpreting the link between excess body weight and GBC risk, possible unmeasured or residual confounding should be considered. Gallstone is closely in related to GBC risk [41]. Meanwhile, obesity tends to be accompanied with DM, which is also associated with increased GBC risk [6,42]. However, most studies did not adjust for these risk factors. This could have led to an overestimation of the true association between obesity and risk of GBC. Second, several studies in this meta-analysis relied on self-reported weight and height measures, which may attenuate the relative risk estimates. However, the summary RR estimates for the studies that had measured weight and height were similar to those on self-reported. Finally, as in any meta-analysis, there was some suggestion of publication bias, because a few studies with null results tend not to be published. However, the results obtained from this study did not provide evidence for such bias.

There was no heterogeneity observed across studies about overweight and GBC risk, and obesity and GBC risk. We analyzed this review in both fixed effects and random effects, and found that they had no significant differences. Thus, the more conservative one, random effects, was chosen finally. Next, when we tried to carry out subgroup analysis to investigate sources of heterogeneity, statistical heterogeneity was lower in analysis of case-control studies, population based studies, Non-Asia studies and BMI ascertainment by self-reported, indicating that these might account for heterogeneity observed in studies about overweight and GBC risk.

In summary, findings of this meta-analysis provide evidence that obesity may increase GBC risk. Further studies that meet epidemiologic criteria on this subject are needed to strengthen the link between BMI and GBC risk, especially those adjusting potential confounding factors such as gallstones and DM.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81401996), and the Medical Research Foundation of Guangdong province (No. A2014228).

References

- Misra S, Chaturvedi A, Misra NC, Sharma ID (2003) Carcinoma of the gallbladder.Lancet Oncol 4: 167-176.

- Foster JM, Hoshi H, Gibbs JF, Iyer R, Javle M, et al. (2007) Gallbladder cancer: Defining the indications for primary radical resection and radical re-resection.Ann SurgOncol 14: 833-840.

- Hsing AW, Bai Y, Andreotti G, Rashid A, Deng J, et al. (2007) Family history of gallstones and the risk of biliary tract cancer and gallstones: a population-based study in Shanghai, China.Int J Cancer 121: 832-838.

- Moerman CJ, Bueno de Mesquita HB, Runia S (1994) Smoking, alcohol consumption and the risk of cancer of the biliary tract; a population-based case-control study in The Netherlands.Eur J Cancer Prev 3: 427-436.

- Ji J, Hemminki K (2005) Variation in the risk for liver and gallbladder cancers in socioeconomic and occupational groups in Sweden with etiological implications.Int Arch Occup Environ Health 78: 641-649.

- Jamal MM, Yoon EJ, Vega KJ, Hashemzadeh M, Chang KJ (2009) Diabetes mellitus as a risk factor for gastrointestinal cancer among American veterans.World J Gastroenterol 15: 5274-5278.

- Hou L1, Xu J, Gao YT, Rashid A, Zheng SL, et al. (2006) CYP17 MspA1 polymorphism and risk of biliary tract cancers and gallstones: a population-based study in Shanghai, China.Int J Cancer 118: 2847-2853.

- Renehan AG, Tyson M, Egger M, Heller RF, Zwahlen M (2008) Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies.Lancet 371: 569-578.

- Larsson SC, Wolk A (2007) Obesity and the risk of gallbladder cancer: a meta-analysis.Br J Cancer 96: 1457-1461.

- Stang A (2010) Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses.Eur J Epidemiol 25: 603-605.

- DerSimonian R, Laird N (1986) Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 7:177-188.

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG (2002) Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis.Stat Med 21: 1539-1558.

- Sterne JA, Egger M (2001) Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis.J ClinEpidemiol 54: 1046-1055.

- Duval S, Tweedie R (2000) Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis.Biometrics 56: 455-463.

- Møller H, Mellemgaard A, Lindvig K, Olsen JH (1994) Obesity and cancer risk: a Danish record-linkage study.Eur J Cancer 30A: 344-350.

- Wolk A, Gridley G, Svensson M, Nyrén O, McLaughlin JK, et al. (2001) A prospective study of obesity and cancer risk (Sweden).Cancer Causes Control 12: 13-21.

- Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ (2003) Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults.N Engl J Med 348: 1625-1638.

- Samanic C, Gridley G, Chow WH, Lubin J, Hoover RN, et al. (2004) Obesity and cancer risk among white and black United States veterans.Cancer Causes Control 15: 35-43.

- Engeland A, Tretli S, Austad G, Bjørge T (2005) Height and body mass index in relation to colorectal and gallbladder cancer in two million Norwegian men and women.Cancer Causes Control 16: 987-996.

- Kuriyama S, Tsubono Y, Hozawa A, Shimazu T, Suzuki Y, et al. (2005) Obesity and risk of cancer in Japan.Int J Cancer 113: 148-157.

- Oh SW, Yoon YS, Shin SA (2005) Effects of excess weight on cancer incidences depending on cancer sites and histologic findings among men: Korea National Health Insurance Corporation Study.J ClinOncol 23: 4742-4754.

- Samanic C, Chow WH, Gridley G, Jarvholm B, Fraumeni JF Jr (2006) Relation of body mass index to cancer risk in 362,552 Swedish men.Cancer Causes Control 17: 901-909.

- Ishiguro S, Inoue M, Kurahashi N, Iwasaki M, Sasazuki S, et al. (2008) Risk factors of biliary tract cancer in a large-scale population-based cohort study in Japan (JPHC study); with special focus on cholelithiasis, body mass index, and their effect modification. Cancer Causes Control 19:33-41.

- Jee SH, Yun JE, Park EJ, Cho ER, Park IS, et al. (2008) Body mass index and cancer risk in Korean men and women.Int J Cancer 123: 1892-1896.

- Song YM, Sung J, Ha M (2008) Obesity and risk of cancer in postmenopausal Korean women.J ClinOncol 26: 3395-3402.

- Hemminki K, Li X, Sundquist J, Sundquist K (2011) Obesity and familial obesity and risk of cancer.Eur J Cancer Prev 20: 438-443.

- Strom BL, Soloway RD, Rios-Dalenz JL, Rodriguez-Martinez HA, West SL, et al. (1995) Risk factors for gallbladder cancer. An international collaborative case-control study.Cancer 76: 1747-1756.

- Zatonski WA, Lowenfels AB, Boyle P, Maisonneuve P, Bueno de Mesquita HB, et al. (1997) Epidemiologic aspects of gallbladder cancer: a case-control study of the SEARCH Program of the International Agency for Research on Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst89:1132-1138.

- Serra I, Yamamoto M, Calvo A, Cavada G, Báez S, et al. (2002) Association of chili pepper consumption, low socioeconomic status and longstanding gallstones with gallbladder cancer in a Chilean population.Int J Cancer 102: 407-411.

- Máchová L, Cízek L, Horáková D, Koutná J, Lorenc J, et al. (2007) Association between obesity and cancer incidence in the population of the District Sumperk, Czech Republic.Onkologie 30: 538-542.

- Hsing AW, Sakoda LC, Rashid A, Chen J, Shen MC, et al. (2008) Body size and the risk of biliary tract cancer: a population-based study in China. Br J Cancer99:811-815.

- Grainge MJ, West J, Solaymani-Dodaran M, Aithal GP, Card TR (2009) The antecedents of biliary cancer: a primary care case-control study in the United Kingdom.Br J Cancer 100: 178-180.

- Nakadaira H, Lang I, Szentirmay Z, Hitre E, Kaster M, et al. (2009) A case-control study of gallbladder cancer in hungary.Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 10: 833-836.

- Alvi AR, Siddiqui NA, Zafar H (2011) Risk factors of gallbladder cancer in Karachi-a case-control study.World J SurgOncol 9: 164.

- Hursting SD, Hursting MJ (2012) Growth signals, inflammation, and vascular perturbations: mechanistic links between obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cancer.ArteriosclerThrombVascBiol 32: 1766-1770.

- Dali-Youcef N, Mecili M, Ricci R, Andrès E (2013) Metabolic inflammation: connecting obesity and insulin resistance.Ann Med 45: 242-253.

- Shebl FM, Andreotti G, Meyer TE, Gao YT, Rashid A, et al. (2011) Metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance in relation to biliary tract cancer and stone risks: a population-based study in Shanghai, China.Br J Cancer 105: 1424-1429.

- Randi G, Franceschi S, La Vecchia C (2006) Gallbladder cancer worldwide: geographical distribution and risk factors.Int J Cancer 118: 1591-1602.

- Cirillo DJ, Wallace RB, Rodabough RJ, Greenland P, LaCroix AZ, et al. (2005) Effect of estrogen therapy on gallbladder disease.JAMA 293: 330-339.

- Gabbi C, Kim HJ, Barros R, Korach-Andrè M, Warner M, et al. (2010) Estrogen-dependent gallbladder carcinogenesis in LXRbeta-/- female mice.ProcNatlAcadSci U S A 107: 14763-14768.

- Stinton LM, Shaffer EA (2012) Epidemiology of gallbladder disease: cholelithiasis and cancer.Gut Liver 6: 172-187.

- Ren HB, Yu T, Liu C, Li YQ (2011) Diabetes mellitus and increased risk of biliary tract cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis.Cancer Causes Control 22: 837-847.

Relevant Topics

- Constipation

- Digestive Enzymes

- Endoscopy

- Epigastric Pain

- Gall Bladder

- Gastric Cancer

- Gastrointestinal Bleeding

- Gastrointestinal Hormones

- Gastrointestinal Infections

- Gastrointestinal Inflammation

- Gastrointestinal Pathology

- Gastrointestinal Pharmacology

- Gastrointestinal Radiology

- Gastrointestinal Surgery

- Gastrointestinal Tuberculosis

- GIST Sarcoma

- Intestinal Blockage

- Pancreas

- Salivary Glands

- Stomach Bloating

- Stomach Cramps

- Stomach Disorders

- Stomach Ulcer

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 16189

- [From(publication date):

August-2015 - Jul 11, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 11559

- PDF downloads : 4630