Short Communication Open Access

Becoming Aware of New Perspectives. The Power of Photography to Frame a Very Personal Story

Jan Sitvast*

Senior lecturer at University of Applied Sciences, Hogeschool Utrecht (HU), Heidelberglaan 7, Utrecht, The Netherlands

Visit for more related articles at International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience

Abstract

Recent news reports (BBC News) show that violence within Burundi is rising again, 12 years after the ending of the bloody civil war between hutu’s and tutsi’s and the genocide on the hutu’s in the nineties of the twentieth century. Tensions are high between former refugees and the population that remained in the area. There is a very high rate of sexual and gender based violence (Cordaid, 2016; WHO Rapport d’Activité, 2014; Ventevogel, Ndayisaba & Van de Put W, 2011). The social support structures in the villages (neighbours helping each other, community leaders solving conflicts in the communities, etc) have been eroded and no longer function well anymore.

Problem Description

Recent news reports (BBC News) show that violence within Burundi is rising again, 12 years after the ending of the bloody civil war between hutu’s and tutsi’s and the genocide on the hutu’s in the nineties of the twentieth century. Tensions are high between former refugees and the population that remained in the area. There is a very high rate of sexual and gender based violence (Cordaid, 2016; WHO Rapport d’Activité, 2014; Ventevogel, Ndayisaba & Van de Put W, 2011).

The social support structures in the villages (neighbours helping each other, community leaders solving conflicts in the communities, etc) have been eroded and no longer function well anymore.

The problem in Burundi and in other post-conflict areas can be summarized as one of community-building and the presence of traumatized people that must be helped with a psycho-social intervention that doesn’t require specific psychiatric knowledge, because there are not enough health care professionals that have been trained in psychiatric disorders. There are

However trained community health care workers (also called psychosocial workers).

“Given the impact of war on large populations, care on individual basis is not realistic. Community-based psychosocial rehabilitation has to be privileged and integrated in the primary health care services to create sustainable responses. At the earliest possible, people with chronic mental disorders and severe trauma should be detected and treated. Non-mental health personnel, given appropriate technical support, have been efficient in responding to the psychosocial distress of refugees.” (Brundtland, WHO Director-general: 1998-2003)

Description of the Proposed Action

We address the problem by selecting a target group that is more vulnerable than other subgroups of the population: youngsters and adolescents. At the same time this is the most promising group for building new communities. The intervention is called hermeneutic photography and combines individual (photo-) stories with a strong accent on how these stories are part of a larger (family/ community) story. The intervention aims at goal finding, expression and representation. These aspects especially appeal to young people on the brink of adulthood. Therefore, the intervention has a special thrill to them. Participants are invited to make photographs of things, settings, persons, etc. that they value as important or dear to them. The resulting photo-stories are shown at a photo-exhibition, organized by participants themselves. This involves the wider community. In a second round (again completed with a photo-exhibition) the focus is on photographing a wish or goal as well as what efforts participants must make to realize their goal.

Because of its focus on strengths and expectancies the approach helps young people to connect their life story with valued goals or relationships and engagements, thus strengthening their resilience. At the same time it carries a diagnostic potential for making visible the suffering of severely traumatized individuals and in this way operates as a portal for referral to further trauma treatment (for instance by traditional healers).

Victims of Violence and Abuse

Studies of women in western countries that were survivors of abuse and violence have shown that a therapeutic intervention in which women were encouraged to reminisce on self-efficacy beliefs and expectancies prior to their personal experiences of abuse had a positive effect (Fry & Barker, 2002). In these studies facilitators of reminiscence groups made sure that the story-tellers did not engage in too much self-criticism or blame as a stick with which to beat themselves. They ensured that a potentially regressive or negative ‘series of events’ or ‘turn of events’ in the narrative of the client about recent life is propelled in the direction of a valued goal or valued relationship or engagement. Thus survivors of violence and abuse were helped to find again a purpose of living, a personal meaning for life even where the present was painfully filled with shame and despair (Fry & Barker, 2002).

Remembering old strengths and values can give new direction in life. Newly found meaning can sustain more socially adapted patterns of behaviour.

We know that the expression of thoughts and feelings within a trusting therapeutic relationship can reduce mental suffering caused by fear, shame and anxiety. The sharing of stories in creative arts therapy and narrative based therapy builds a strong sense of connection and fellowship. It may help young people to imbue their personal story with greater significance and meaning, as well as coherence (Maruna & Ramsden, 2004).

We combined both approaches in hermeneutic photography. Making photographs is an playful way of expressing oneself, that requires no special skills (thus being different from other forms of art therapy). The magic of making images will appeal to young people.

METHODS

Hermeneutic Photography

The intervention spans 2 x 8 photo group sessions, each series finished with an exposition of the photo stories. Participants select a limited number of their photographs with text to show at the exhibition. This guarantees a commitment and strengthens accountability for one's story and ultimately for actual 'real' lives they represent. From art therapy we introduced photographs, because from literature we knew that there were elements of participants’ experiences that could not easily be presented in a coherent logical narrative (Maruna & Ramsden, 2004). Photographs often trigger a reflective process in which images become the carriers of symbolic and metaphoric associations, even where the photographer had no clear idea when taking his pictures (Hagedorn, 1996; Sitvast, 2014).

The facilitators of the group invite participants to tell what the pictures mean and asks questions in a dialogical way. Group members can also ask for explication. There is no contesting the validity or truth of what someone tells. Facilitators have a non-judgemental attitude in this respect. However, learning the stories of other group members will open up new perspectives and contributes to a more reflexive stance (Sitvast, Abma & Widdershoven, 2008). The sharing of stories among group members prevents denial of shame and substitution of shame by anger (Nathanson, 1992). The structured and dosed build-up of the intervention helps containing emotions that concur with newly found insights (Randall & Kenyon, 2002). An important aspect of the therapy is that there is no direct confrontation with traumatic experiences. The assignment that sets the topic to be photographed focuses on: a) what one considers valuable in life and b) wishes or goals one would want to realize.

Of course experiences from the past may interfere with acting upon what one values most. These experiences may then be reflected upon but they remain contained within an agenda of growth, development and realizing positive aims.

Although talking about one’s experiences with violence and abuse is not the intervention’s primary aim, when it happens it relieves the pain of isolation and alienation caused by feelings of shame. When people hear stories of others they identify with them and recognize themselves in them. This sharing of experiences draws them out of their isolation. It can build a connection between members of the photo group which can be extended to family (and the larger community) when steps are taken to explicitly involve relatives in the process.

The social context of the photo group acts as a motivator to discover and take on responsibilities, both for one’s life as well as towards others. It provides the context for a relational and moral learning. The focus on a ‘valued life’ will help victims of violence to reorient their lives and find new meaning.

The experience of sharing one’s photo stories with others contributes to opening up, connecting again with values, wishes and options in life and prepares someone for first steps to realize personal goals. This widening space for reflection, the chance to express and represent oneself through images and text and the sharing are aspects of the moral and the psychological conditions for a successful recovery from trauma (Anckerman et al., 2005).

The sharing and expressing of experiences through photo stories can be reinforced by translating newly found meanings into dance and music and thus hermeneutic photography may connect with more traditional African mediums of expression. The collective action and cooperation necessary for staging the photo exhibition and accompanying dance and music will build community feelings. This will be even more effective when the community adopts the revealed wishes and goals of the youngsters and facilitates their realization: for instance in the form of a training of professional skills to help them set up in small business.

Technical Facilities

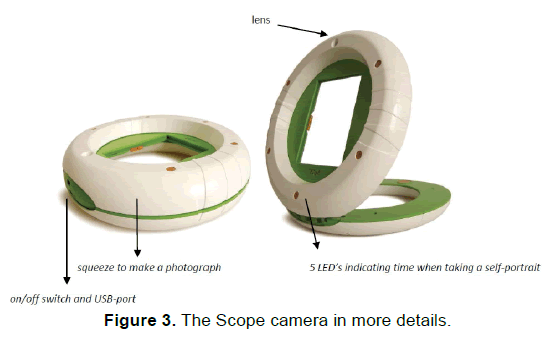

Crucial in our proposal to adopt hermeneutic photography in Burundi (or in other post-conflict areas) is the availability of photo camera’s and the technical facilities to use them in a environment that doesn’t have easy access to technical support and retail provisions. That’s why we cooperated with an industrial designer who developed a special camera to be used by underprivileged strong>children, e.g. children living in (former) warzones. Children can take photographs and self-portraits in order to rediscover their environment and identity, and share their point of view with others. With its open-steering-wheel design (you click the shutter by squeezing the sides), Scope invites a new perspective on picture-taking, removing the distance between the photographer and her subject.

“I wanted to emphasize the importance of looking and framing. In my design there is no screen ... It places the photographer in the spotlight: while looking through the camera, the world looks at you. You cannot hide behind the camera” (Bas Groendaal).

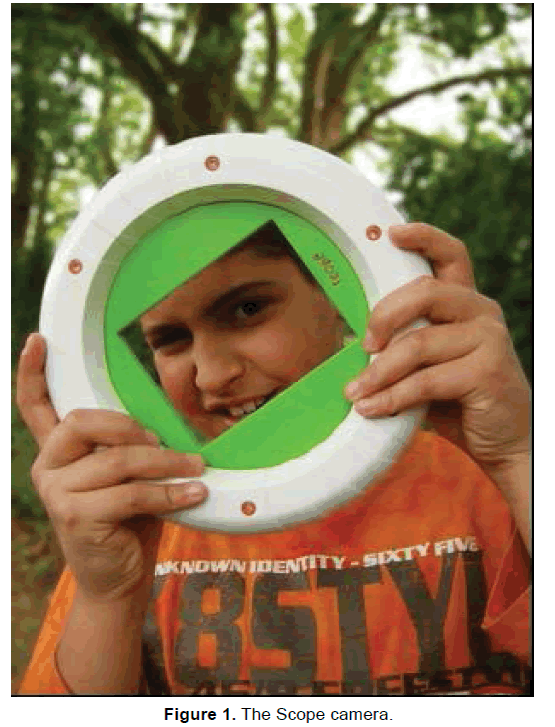

Groenendaal took the Scope prototype to an asylum-seekers center in the Netherlands, where the kids quickly figured it out (Figures 1-3):

"A funny observation was that the children used Scope to frame their own heads: hold the camera really close to their face and -- while talking -- look at everybody around them. The children seemed very conscious of themselves, their position, what they were seeing. It's an illustration of the power of photography to frame a very personal story.….”

The Scope does not contain a screen, therewith removing the most expensive and energy consuming part of a camera. Scope can be ‘opened’ to function as camer-stand, which makes it easier to make self-portraits with the timer-button on the inside. The energy provision of Scope can be done by solar cells or ‘winding up’ the camera. The design of the Scope is robust, and easy to use. The camera is already digital. Photographs can be printed from a photocopier/printer.

Planning

The intervention can be facilitated by the community health care workers. Members of a photo group may be trained to become facilitators of new photo groups. In this way the intervention can be disseminated in a wider area. Having photo groups facilitated by experiential experts (instead of professionals) contributes to stronger empowerment. Training of experiential experts can be expanded into further training opportunities to become community workers in their own right. Photo groups can best be organized in the local communities. Several photo groups can share a photocopier/printer. Costs for the Scope camera needn’t be high, especially when we find sponsors.

The intervention is not difficult to learn. Community health workers can easily be trained to implement a photo group. The photo exhibition has its greatest impact when it is highlighted as social event, thus contributing to strengthening the community. The diagnostic potential of the intervention can be optimized by alerting the community health workers to the specific rhetoric of photo stories determined by trauma that needs further treatment by traditional healers.

Evaluation

The project will be a success when a community rallies around its youth on the occasion of the photo exhibition and when the photo stories are an impetus to set up follow-up projects to realize the dreams and goals of the young. Then the intervention breeds new hopes and connects people. A further criterium for success is whether the intervention can filter out those young people who are so severely traumatized that they need special attention and referral to traditional healers.

The limitations of this project can be found in its dependence on possibilities to give a follow-up to the aspirations of the young people who participated. Imagining one’s life and not be able to act upon it would smother hope and breed despair in the long end.

Obstacles for a successful implementation of the intervention may be specific cultural notions around images and images taken that we are not aware of, but which may interfere with acceptation of the intervention.

References

- Anckermann S., Dominguez M., Soto N., Kjaerulf F., Berliner, P. & Mikkelsen, E.N. (2005). Psycho-social Support to Large Numbers of Traumatized People in Post-conflict Societies: An approach to Community Development in Guatemala. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology,15: 136-152

- BBC News: www.bbc.co.uk, world-africa-13085064. Acceses on January 2nd, 2016

- Brundtland, G.H. (2000). Mental health of refugees, internally displaced persons and other populations affected by conflict (editorial). Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 102, 159-160

- Cordaid, country report: https://www.cordaid.org/en/projects/?countries=BI. Accessed on January 1st, 2016

- Fry, P.S. & Barker, L.A. (2002). Female Survivors of Abuse and Violence: The Influence of Storytelling Reminiscence on Perceptions of Self-Efficacy, Ego Strength, and Self-Esteem, in: Webster, J.D. & Haight, B.K. (Eds), From Theory to Application, New York: Springer Publishing Company

- Groenendaal, B., (2007). Scope: Master Graduation Report, University of technology Eindhoven: Department of Industrial Design

- Groenendaal, B., (2008): www.basgroenendaal.nl

- Groenendaal: http://blog.ted.com/2008/08/prototype_camera.php

- Hagedorn. (1996). Photography: an aesthetic technique for nursing inquiry. Issues in Mental Health Nursing,17, 517-527

- Maruna, S. & Ramsden, D. (2004). Living to Tell the Tale: Redemption Narratives, Shame management, and Offender Rehabilitation, in: Lieblich, A., McAdama, D.P. & Josselson, R. Healing Plots. The narrative Basis of psychotherapy. Washington: American Psychological Association

- Nathanson, D.L. (1992). Shame and pride: Affect, sex and the birth of the self. New York: W.W. Norton

- Randall, W.L. & Kenyon, G.M. (2002). Reminiscence as Reading Our Lives: Toward a Wisdom Environment, in: Webster, J.D. & Haight, B.K. (Eds), From Theory to Application, New York: Springer Publishing Company

- Sitvast, J.E., Abma, T.A. &Widdershoven, G.A.M.. (2008). Photostories, Ricoeur and Experiences from Practice. A Hermeneutic Dialogue. In: Advances in Nursing Science, 31(3), 268-279

- Sitvast, J.E., Abma, T.A.,&Widdershoven G.A.M. (2010). Façades of suffering:cllients’ photo stories about mental illness. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing,24(5), 349-361

- Sitvast, J.E. (2009). How to verbalize difficult experiences and emotions with the use of photographs, in: Ian Needham, Tom Palmstierna, Henk Nijman & Nico Oud, Violence in Clinical Psychiatry, Dwingeloo (Netherlands): Publisher Kavanah

- Sitvast, J. (2014). Hermeneutic Photography. An innovative intervention in psychiatric rehabilitation founded on concepts from Ricoeur. Journal of Mental Health Nursing

- Sitvast, J.E.: www.fototherapie.startje.com (in Dutch)

- Ventevogel, P., Ndayisaba, H. & Van de Put, W. (2011). Psychosocial assistance and decentralised mental health care in post conflict Burundi 2000- 2008. Intervention, Journal of mental health and Psychosocial Support in Conflict Affected Areas 2, Volume 9, Number 3, Page 315 – 331(War Trauma Foundation)

- WHO Rapport d’Activité (2014). Bujumbura (Burundi): OMS.

Relevant Topics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 10921

- [From(publication date):

March-2016 - Jul 12, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 9923

- PDF downloads : 998