Review Article Open Access

Barriers to Engagement in Acute and Post-Acute Sexual Assault Response Services: A Practice-Based Scoping Review

Kristy Fitzgerald1, Sally Wooler2, Dara Petrovic3, Jen Crickmore3, Kristy Fortnum3, Letitcha Hegarty4, Chantal Fichera5, Pim Kuipers6,7*1Department of Social Work and Psychology, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Queensland, Australia

2Acquired Brian Injury Transitional Rehabilitation Service, Metro South Health, Queensland, Australia

3Department of Social Work, Logan Hospital, Metro South Health, Queensland, Australia

4Maternity and General Medical, Beaudesert Hospital, Metro South Health, Queensland, Australia

5Cancer Support Team, Wide Bay Health, Queensland, Australia

6Centre for Functioning and Health Research, Metro South Health, Queensland, Australia

7Menzies Health Institute Queensland, Griffith University, Queensland, Australia

- *Corresponding Author:

- Pim Kuipers

Menzies Health Institute Queensland

Griffith University, Queensland, Australia

E-mail: p.kuipers@griffith.edu.au

Visit for more related articles at International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience

Abstract

Background: Engaging victims of sexual assault in acute and post-acute sexual assault services is vital for their immediate and longer term wellbeing, but is also a major challenge for practitioners and services. Methods: A practice-based scoping review was conducted to identify barriers to engagement. After search limiters were applied, 339 articles were screened at various levels, resulting in 27 articles, which were reviewed by two reviewers and appraised for quality and relevance. Results: Eighteen key barriers were identified within the four categories of: service and system barriers, health professional barriers, person/survivor barriers, and person context barriers. Conclusion: The identified barriers provide a useful guide for practitioners as key issues to address or consider when seeking to promote greater victim/patient engagement in acute and post-acute sexual assault services. The need for a “victim centred response” is highlighted..

Keywords

Sexual assault, Rape, Acute hospital, Post-acute hospital, Patient engagement, Scoping review

Introduction

The provision of social work services in response to sexual assault is vital. Social workers are often the first professionals with whom victims1 of sexual assault come into contact (McClennen et al., 2016). Many such social work interventions occur in acute settings, such as a hospital emergency departments (ED) or crisis centres. In such contexts, it is the responsibility of the social worker to respond to the needs of the individual in many ways, including through information provision, support, counselling, referral and advocacy (McClennen et al., 2016).

It is important for victims of sexual assault to obtain adequate and timely support in these settings. They may be at risk of psychological, emotional and social crises, as well as needing attention for physical injuries, genital injuries, gynaecological complications, unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (McClennen et al., 2016). When victims do not access support, not only is their physical health jeopardised, but the consequences on their everyday life can also be devastating (Australian Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health, 2011). Survivors often report feelings such as shame, terror, and guilt and self-blame. Victims who fail to engage in follow-up support are at increased risk of suffering negative mental health outcomes such as depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress, relationship issues and substance addiction (KPMG, 2009).

In several Queensland public hospitals, specialised sexual assault services provide a co-ordinated response addressing medical and forensic issues in addition to counselling and support services (KPMG, 2009). Support is available face to face, on the hospital grounds, at other locations, or via the telephone. As a profession tasked with delivering and coordinating responses to acute and postacute sexual assault, hospital social work services provide client centred support on a 24 hour a day basis. Interventions typically involve initial trauma counselling, risk assessment and intervention planning, as well as facilitating access to practical support, assisting decision making within the legal context (including the provision of formal reports), and short-to-medium-term counselling in a private, confidential, and safe environment at no cost to the client/patient.

A key challenge for all sexual assault response teams is ensuring that their services are responsive to the needs of victims. It is recognised that regardless of the professional make-up of such a team (Moylan et al., 2017), or the method of service provision (Steinmetz & Gray, 2017); one of the most pressing issues is ensuring that victims engage in, and draw benefit from available services. For this to occur, service/organisational leaders and clinicians must understand key barriers and enablers of such engagement.

It was recognised within the social work management team at Logan Hospital, (Queensland, Australia), that many patients who present to public hospital emergency departments as a result of a suspected or declared sexual assault, do not follow through with referrals or do not engage with the triage, emergency, crisis support or follow-up care being offered. The Logan Hospital social work team noted the need for practice-relevant research in this area (Greeson & Campbell, 2013), and met to discuss this topic, and to formulate a research plan. Recognising that traditional PICO format (Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) approach to conceptualising research was not relevant to the nature of this issue, more general research methods were explored.

AIMS

In response to the above issues, the Logan Hospital Social Work Department conducted a practice-based scoping review to gather information regarding barriers to client engagement in acute and post-acute sexual assault services. The research question was, “What are the barriers to client/patient/victim engagement in acute and post-acute sexual assault services?”

Secondary aims of the review were: to engage social work practitioners in critical appraisal of relevant research, to explore methods which contribute to practice-relevant evidence, and to inform planning for inpatient social work services.

Scoping Reviews

An important way of establishing evidence in social work and related areas is conducting some form of review or overview of the literature (Rozas & Klein, 2010). In this case “scoping review” methods were identified as suitable (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005), particularly where a collaborative, group approach is used (Levac et al., 2010).

Scoping reviews are comprehensive and rigorous surveys of the literature to identify key concepts, and describe the nature of evidence on a topic (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005). Within the scoping review process, the available literature within a defined set is identified through a bibliographic data base search, screened for Reviewalignment with the research question, summarized, (in this case, ranked for quality and relevance), and then thematically analysed in a collaborative process to determine key issues. Such reviews have been used in a range of health and welfare settings, and found to be particularly useful for identifying available evidence and noting research gaps in complex or emerging areas (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005, Anderson et al., 2008).

Recognising that the available literature pertaining to this issue was mixed, it was agreed that the highest quality and most clinically relevant studies should provide the greatest weight of evidence in the review (Ogilvie et al., 2008). Consequently it was determined that the scoping review methodology would be adapted to also incorporate ratings of the quality and relevance of each included article, (Daudt et al., 2013). The review was conducted as a practice-based research initiative, with social work practitioners leading the review, supported by an experienced research mentor (Daudt et al., 2013), and with decisions and criteria being influenced by the concerns and realities of practitioners.

Methods

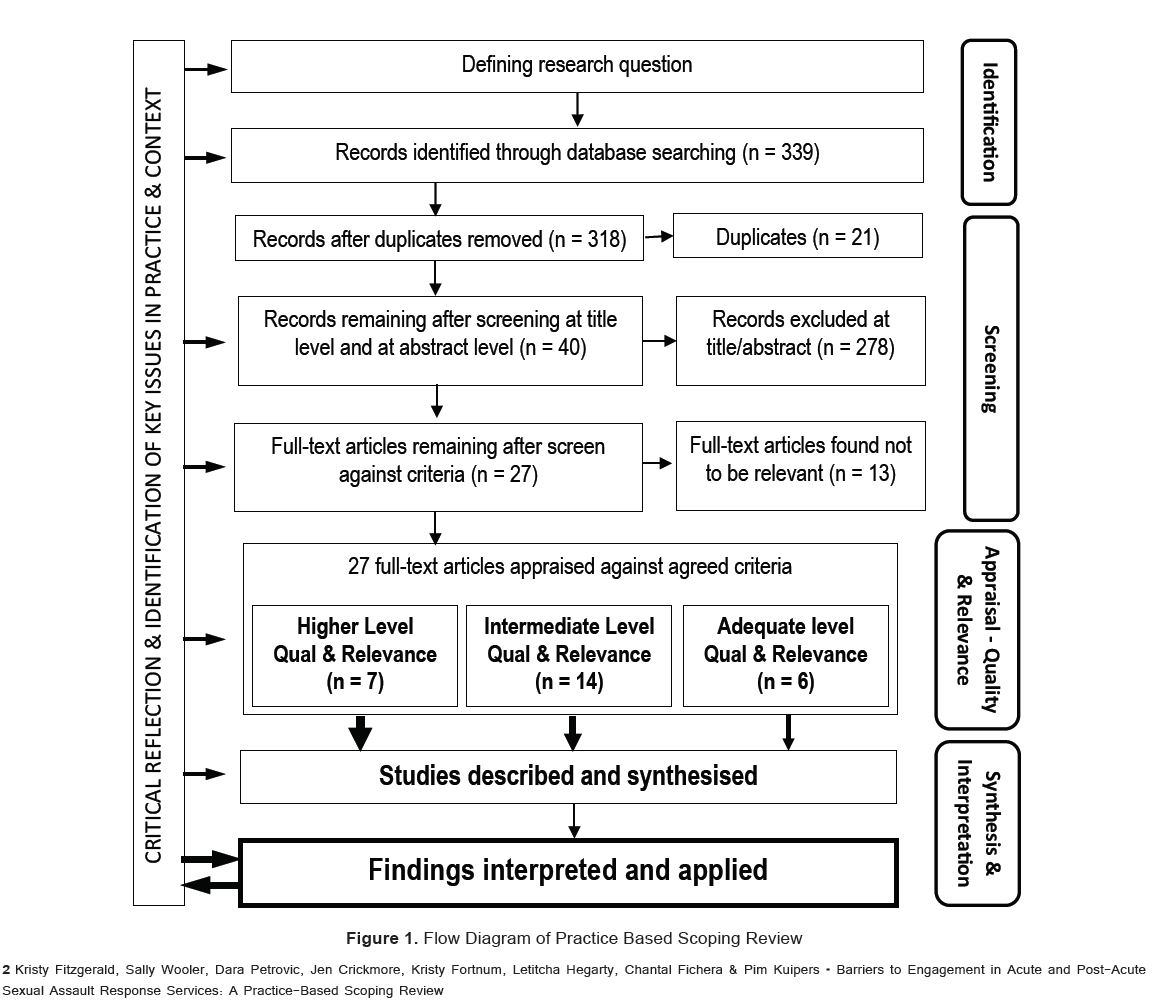

This study adapted a number of steps from existing frameworks (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005), presented diagrammatically (Figure 1). Based on the question, a number of search terms were considered and a search was undertaken on CINAHL Complete, PsychINFO, and SocINDEX bibliographic databases. Using the search terms identified (Table 1), 6186 hits were identified in the literature from the year 2000 onwards. These were limited to academic journal articles available in English. To enhance relevance of articles to

| Category | Search terms selected |

|---|---|

| Service Context | Health facilit* or hospital or hospital program or forensic or service or center or clinic |

| AND | AND |

| Patient/victim/client context | Sexual assault or sexual abuse or rape or intimate partner violence or domestic violence |

| AND | AND |

| Research focus | MH “Health Services Accessibility” or MH “Communication Barriers” or barriers or access or engage* |

Table 1: Agreed search terms

be reviewed, subject limiters identified by the search engine were applied, namely:

• “Major Subject” limit terms (treatment, survivors, help seeking behaviour, trauma, emotional trauma, sexual partners, physical abuse, rape, partner abuse, mental health, violence, victimization, human females, intimate partner violence, sexual abuse)

•“Subject” limit terms (safety, psychotherapy, risk assessment, longitudinal method, correlation (statistics), statistics, counselling, behaviour, thematic analysis, sampling (statistics), interviews, surveys, data analysis, questionnaires, descriptive statistics, psychosexual behaviour, at risk populations, research, health services accessibility, prevention).

This resulted in 339 “hits”

1. After removal of duplicates, the titles and abstracts of all 318 hits were retrieved and read by two team members, who screened them for alignment with the research question. Of these, 278 were identified as not directly

2. The remaining 40 articles were retrieved and downloaded. Each was read by two team members independently. They ranked each article for quality and relevance, and documented key points or findings that pertained to the research questionrelevant to the question.

(Appendix 1). They then discussed their ratings and established consensus on a final rating of quality and relevance for each article.

3. Based on agreement, articles were then categorised at three levels of relevance and quality (Appendix 1).

4. In a four stage collating and summarising exercise, team members established a classification structure based on the content of the higher quality and higher relevance articles. The categories in this structure were discussed within the team to ensure congruence. In the second stage, the team extracted from each of the higher quality and relevance articles, key points that pertained to the research question, specifically noting barriers and enablers to consumer engagement. These were categorised using the developed structure. In the third and fourth stages, the team used the classification structure to include any other information drawn from articles that were classified as intermediate level and lower level quality and relevance. In this way the information obtained from higher quality and higher relevance articles had the greatest prominence in the derived evidence.

Results

The scoping review identified a number of barriers from the selected literature. While many related to hospital based services, others could be extrapolated from other acute and post-acute settings. Key categories evident in the reviewed literature were: service and system barriers, service provider/health professional barriers, person/survivor barriers and person/survivor context barriers. These are detailed below and summarised in Table 2.

| Barrier Identified | Example | |

|---|---|---|

| Service and system barriers | Access | Transport, physical access, service availability, rurality |

| Safety | Perceived risk of police, legal or child protection intervention. Likelihood of justice | |

| Referral failures and delays | Poor coordination, inappropriate referrals, inadequate referral information | |

| Inadequate support for sub-populations | Persons with learning disabilities, people from culturally diverse backgrounds | |

| Previous negative experiences with similar systems | ||

| Service constraints and time pressures | Staff perceived as un helpful, uncaring, inflexible | |

| Discriminatory practices | Language barriers, lack of cultural competence, insensitivity to gender roles and values | |

| Health professional barriers | Attitudes and practices | Uncaring or unsupportive professionals, blaming attitudes, negative race or class bias. Questioning style of professionals and the way a forensic medical examination is conducted. |

| Time | Hurried staff or quick-fix solutions, failing to validate the client’s experience | |

| Rigid services | Inflexible services, silo-driven approach, inconsistencies | |

| Staff competence | Inexperience or unskilled staff without adequate training. | |

| Patient/victimindividual barriers | Mental health concerns | Existing mental health and cognitive issues. Mental health consequences of the sexual assault, including guilt and shame. |

| Fear of retaliation | Feeling vulnerable, concern for children | |

| Failure to interpret the event as violence | Cultural norms, accepting of violence, confused understanding of love | |

| Financial constraints | Costs of getting to the service.Concern over possible expenses. Financial dependence on others | |

| Patient/victim context barriers | Community and social factors | Cultural constraints, protecting others, including community.Culturally expected gender roles |

| Perpetrator factors | Protecting perpetrators, nature of relationship with perpetrator and the physical presence of perpetrator | |

| Family factors | Sacrificing self for children, protecting the immediate or extended family, family sanction or permission |

Table 2: Summary of barriers identified in the literature.

Service and System Barriers

A number of service and system barriers to client engagement in acute and post-acute sexual assault services were described in the studies reviewed. Fundamentally, access was noted as a primary system barrier for those requiring post-acute sexual assault services, and was a recurrent issue raised throughout the literature (Guruge & Humphreys, 2009, Larsen et al., 2014, Lutenbacher et al., 2003,

Beaulaurier et al., 2008). Restrictions (or perceived restrictions) to patient access, such as transport difficulties, location, accessibility, distance, limited opening hours, lack of childcare and even ambiguity about how and where to enter the system, were key themes (Guruge & Humphreys, 2009, Larsen et al., 2014, Lutenbacher et al., 2003, Bent-Goodley, 2004). For adolescents, there are inherent access barriers that must be acknowledged, such as difficulties with transport and scheduling (Kulkarni et al., 2011).

The issue of access was highlighted as a major concern in rural services and resource-constrained settings, where services and resources may be few and geographically dispersed (Kulkarni et al., 2011, Kulkarni et al., 2010, Logan et al., 2003), and where there may be limited community awareness of such services (Logan et al., 2005). Beyond the obvious constraints of distance, in rural settings, there may be a lack of priority on sexual assault cases, and they may not be treated as an emergency (Logan et al., 2005). Likewise, limited associated services such as advocacy (Logan et al., 2005), or the potential for incurring direct or indirect debt can be a further barrier for rural women who have experienced violence (Kulkarni et al., 2011).

Second, the extent to which services are (and are perceived to be) safe, is vital. How safe the patient perceives the environment to be, their perceived risk from legal or child protection intervention (Kulkarni et al., 2010) or the level of control they perceive within a particular situation is often linked to whether or not they will disclose sexual assault (Lutenbacher et al., 2003). Indeed, any failure to create a safe space for patients would constitute a significant system limitation and potential barrier (Larsen et al., 2014, Gerbert et al., 1997, Kelly, 2006). For many, a key aspect of patients feeling safe and confident within a system depends on whether they feel reassured that their disclosure will lead to justice (Kelly, 2006). Without this reassurance, patients may deny rape (Lutenbacher et al., 2003). Recognising that some victims may perceive the police and legal/justice systems as threatening and to be avoided (Kulkarni et al., 2010, Logan et al., 2003), is another key challenge for service providers who may encourage them to seek justice, which cannot necessarily be guaranteed (Kelly, 2006).

Beyond the initial dimensions of access and safety, delays and poor coordination with social workers were seen as service barriers (Davies et al., 2001). Similarly, poor coordination from acute to post-acute care and services was found to result in an inconsistent and fragmented intervention which affected client engagement (Guruge & Humphreys, 2009, Larsen et al., 2014, Edmond et al., 2013, Reisenhofer & Seibold, 2013). Since acute settings respond to crisis, and do not usually provide long term intervention, referral of patients to ongoing specialised support and counselling services is typically a core function (Edmond et al., 2013). If there is inadequate or inappropriate referral information, women may become disengaged from the health care system (Larsen et al., 2014). Likewise, if referrals are done poorly, without adequate attention to eligibility criteria and available resources, or if referrals are made to irrelevant services or programs with long waitlists, they may foster feelings of isolation, and adversely affect the persons' motivation to seek help, which constitutes a further barrier (Guruge & Humphreys, 2009, Beaulaurier et al., 2008, Bent-Goodley, 2004, Edmond et al., 2013).

According to the reviewed studies, the absence of required supports for particular sub-populations also constituted a barrier (Guruge & Humphreys, 2009, Howlett & Danby, 2007). For example, people with learning disabilities may require specific care and advocacy (Howlett & Danby, 2007). Likewise, those from culturally diverse backgrounds may require culturally and linguistically appropriate services (Guruge & Humphreys, 2009) due to their limited education and low levels of English language proficiency (Bui, 2003). Without appropriate supports, such sub-populations may not be able to engage meaningfully.

For some, previous negative experiences with similar services were noted to be a barrier to their future engagement. When victims have had negative experiences in previous dealings with the health system, their trust in the service is undermined (Reisenhofer & Seibold, 2013), which is a further barrier.

Service constraints leading to time pressures within the services were also noted as a significant issue in the reviewed literature. When attending services which are rushed or which put health professionals under time pressures, patients may feel that the health professionals are unhelpful or uncaring, which hinders disclosing sexual assault, accessing support or engaging in health care (Gerbert et al., 1997, Kelly, 2006). Similarly, when services lack flexibility, or undermine the patient’s sense of control, it may result in feelings of defeat (Lutenbacher et al., 2003, Beaulaurier et al., 2008, Howlett & Danby, 2007), which also precludes meaningful engagement.

Discriminatory or racist practices within services are profound barriers to engagement (as well as violations of human rights (Guruge & Humphreys, 2009)). However more subtle barriers that may impact on clients from other cultures, such as language barriers, lack of cultural competence when exploring sensitive issues, inappropriate or direct questioning, lack of understanding of different values and gender roles, as well as insensitivity to concerns over citizenship and deportation were identified in the review (Bent-Goodley, 2004, Kelly, 2006). As noted above with regard to safety, the failure to create a culturally appropriate and safe space for clients to disclose assault (Kelly, 2006) constitutes a significant system failure (Larsen et al., 2014, Gerbert et al., 1997).

health professional barriers

As expected, the review noted that frontline workers in acute sexual assault services play a vital role in engaging people who have experienced sexual assault. Conversely the actions of frontline workers and health professionals can also be significant barriers. The expressed attitudes (as well as practices) of professionals have profound impacts on the patient’s engagement with services (Campbell et al., 2001, Du Mont et al., 2009). Where victims perceive that clinicians are uncaring or unsupportive (Gerbert et al., 1997, Kelly, 2006, Du Mont et al., 2009), they may feel invalidated (Lutenbacher et al., 2003) and withdraw. In particular when they perceive ‘blaming’ attitudes (Du Mont et al., 2009, Oneha et al., 2010), or negative bias (race or class) (Ullman & Townsend, 2007), they are likely to disengage. Since previous unsatisfactory experiences with health professionals also impact on victims (Harper et al., 2008), they can also be barriers which may not be evident in the current encounter.

In hospital services, which focus on crisis and referral, the questioning style of the clinician is a critical factor; if this is done in an inappropriate or officious manner, not allowing the person to share their story, barriers will be encountered (Kelly, 2006). The way in which health professionals deal with the issue of possible forensic medical examination, explaining implications and providing education, is also very important (Du Mont et al., 2009). Such examinations can be very difficult for the victim and cause re-traumatisation, so the supportiveness of health professionals and the forensic medical officer are crucial (Du Mont et al., 2009).

Some studies noted the importance of allowing adequate time for health care professionals to address issues other than the presenting injury (Gerbert et al., 1997). Seeking a quick fix solution through medication prescriptions, rather than listening and being attentive to the patient (Larsen et al., 2014), or not taking the time to adequately validate the client’s experience (Ullman & Townsend, 2007), were also identified as barriers.

It was noted in the review that inconsistent interventions (over time or between professionals) can have negative implications on patients (Ullman & Townsend, 2007). Inflexible services, which may be manifest in professional practice “silos” are also a barrier (Larsen et al., 2014, Gerbert et al., 1997). Indeed, inappropriate services and misguided interventions from health professionals can lead to secondary victimisation of those who have experienced sexual assault (Campbell et al., 2001).

The reviewed literature indicated that the competence of health professionals, their confidence and their experience in working with victims of sexual assault impacts on engagement (Logan et al., 2005, Gerbert et al., 1997, Du Mont et al., 2009). Experienced, supportive and highly skilled health professionals are vital in this context (Harper et al., 2008), however, it should also be acknowledged that the work is difficult, and staff burn-out undermines the provision of optimal interventions for people who have experienced traumatic sexual assaults (Ullman & Townsend, 2007). Adequate training and care of proficient staff would appear to be an important means of addressing a number of potential barriers.

Patient/Victim Individual Barriers

The reviewed literature indicated four key themes relating to the assault victim. First, existing mental health concerns, anxiety, depression, or substance abuse (and also any cognitive impairments, and physical disabilities) can all contribute challenges to patient engagement in cases of sexual assault (Kulkarni et al., 2010). The serious physical and mental health consequences of the sexual assault itself were also noted as key barriers (Larsen et al., 2014), including reduced self-esteem, depression (Howlett & Danby, 2007), extreme embarrassment and feelings of humiliation (Gerbert et al., 1997). These may lead to self-harm (Howlett & Danby, 2007), substance abuse, eating disorders (Howlett & Danby, 2007) and deterioration in mental health; all of which in turn are barriers to initial engagement, reducing the likelihood of victims seeking support, and further perpetuating a vicious cycle (Edmond et al., 2013).

Commonly, feelings of guilt shame and self-blame are barriers to engagement (Logan et al., 2005, Reisenhofer & Seibold, 2013, Harper et al., 2008). Likewise, feelings of powerlessness, hopelessness and desire for secrecy also constrain help-seeking in the context of sexual assault (Beaulaurier et al., 2008). Even the anticipation of the encounter with the health service, re-traumatisation (Larsen et al., 2014, Ullman & Townsend, 2007), especially during forensic examinations (Du Mont et al., 2009) and the fear of being blamed (Oneha et al., 2010), can be major barriers to meaningful engagement.

Second, sexual assault victims may experience fear of retaliation and vulnerability (Kelly, 2006, Du Mont et al., 2009), for themselves or for their children (Kelly, 2006, Reisenhofer & Seibold, 2013) if they pursue justice (Oneha et al., 2010). For some, the possibility of dealing with the police and justice system may be itself a barrier to engagement (Kelly, 2006). Clearly concerns regarding confidentiality and how their personal information will be used, is a potential barrier (Gerbert et al., 1997). The need for disclosure undermines engagement (Larsen et al., 2014), particularly where there have been previous negative experiences of disclosing sexual assault (Lutenbacher et al., 2003) or inconsistent services that did not engender trust (Gerbert et al., 1997). In rural areas, and small communities, concerns over confidentiality and trust may be particularly pronounced (Logan et al., 2005).

Third, the review also identified that a consistent barrier to engagement in services following a sexual assault is the victim’s non-recognition of the events as violence (Reisenhofer & Seibold, 2013, Kelleher & McGilloway, 2009, Peterson et al., 2005, Neill & Peterson, 2014). Cultural or intergenerational norms about gender and violence (Kulkarni et al., 2011), different perceptions of violence ( Bent-Goodley, 2004, Kelleher & McGilloway, 2009), confused understandings of love (Kulkarni et al., 2011), as well as different language and definitions, impact on whether they actually define the experience as violence, and whether they go on to accept support services ( Bent-Goodley, 2004, Kelleher & McGilloway, 2009).

Finally, a very practical, but important concern for some victims is their financial status (Larsen et al., 2014). Costs associated with services (Logan et al., 2005) or transport to appointments, medications, replacement of clothing, other items, finding new housing or medical fees have all been noted as a significant concern for people accessing support. This is particularly highlighted where women and children rely on the perpetrator for financial or other support (Guruge & Humphreys, 2009). For many women with limited financial resources, including adolescents and those from some ethnic communities, there are financial barriers to attending services (Kulkarni et al., 2011, Lipsky et al., 2006). Similarly, those who do not have resident status may not have access to crisis payments for welfare assistance (Guruge & Humphreys, 2009), which presents a further problematic barrier.

Patient/Victim Context Barriers

Contextual barriers identified in the current review spanned from simple lack of information or misperceptions about services (Logan et al., 2005, Neill & Peterson, 2014), to pervasive racial, cultural and social factors which preclude engagement. Victims may place themselves (including their safety) as secondary to what they perceive as the greater good of their family and community, despite potential physical, psychological and spiritual harm (Bent-Goodley, 2004). This may include protecting perpetrators from imprisonment or the criminal justice system (Oneha et al., 2010), or protecting the family and community from embarrassment (Lipsky et al., 2006). Similarly some women may be reluctant to speak to hospital social workers due to concerns of race, class, mistrust, or believing that child services only pertain to child abuse (Lutenbacher et al., 2003)

Regarding roles, the review noted that some vulnerable women suffer “gender entrapment”. That is, through societal and family expectations, or the media, they may be penalised for behaviours which are logical extensions of their realised identities, their culturally expected gender roles, and the violence in their intimate relationships (Beaulaurier et al., 2008, Bent-Goodley, 2004). In such cases, the complexity of the victim’s cultural context must be sensitively understood. For some, a key barrier is the prospect of losing family support or religious disapproval if they talk about experiencing sexual assault or domestic violence (Beaulaurier et al., 2008, Bent-Goodley, 2004).

Beyond those from different cultures, victims with children, particularly older children, or male children, male victims, gay, lesbian and transgendered victims, and those whose abusers are in law enforcement, may also be less likely to engage (Kulkarni et al., 2010). Where the perpetrator is known to the victim, such as intimate partner violence, there is often greater hesitancy to engage (Kaukinen, 2004, McCall-Hosenfeld et al., 2009). In cases where the victim presents to an emergency department with their abuser, who may control their access to services, true cases of injury may be concealed or described by the partner as something else (Reisenhofer & Seibold, 2013). As noted above, general fear of the perpetrator or of specific retaliation by the perpetrator if the assault is revealed is another important barrier (Logan et al., 2005).

From a family unit perspective, sexual assault and domestic violence are highly complex with some women being unwilling to change their relationship with their abuser or making personal sacrifices for the sake of their children (Kelly, 2006). Such internal barriers are highly complex and pertain to self-blame, powerlessness, hopelessness and secrecy (Beaulaurier et al., 2008). The threat of loss of income, disruption of relationships with children or family sanction, or even concern over potential imprisonment of the abuser is another potential obstacle o engagement (Beaulaurier et al., 2008). For young women who have experienced assault, there are also barriers such as requiring parental permission to attend certain support services or to access healthcare (Kulkarni et al., 2011).

In some cultures, pressures from and conflicts within the community, pertaining to the impact of separation on children and other family members is a factor (Guruge & Humphreys, 2009, Lipsky et al., 2006). For women from some ethnic groups, language and cultural differences are key barriers (Lipsky et al., 2006). Women, who do not speak fluent English, may keep their situation confidential within the community (Guruge & Humphreys, 2009). In some contexts, violence is understood to be a family matter, dealt within the family or by one’s self (Oneha et al., 2010).

Quality and Relevance of Articles Reviewed

As noted in Figure 1, an aspect of the review process was rating each of the articles for quality and relevance. Where possible the authors sought to allow the evidence from those articles which most closely aligned with the criteria to determine the categories of the review. The focus across the seven higher quality and relevance articles reviewed (Lutenbacher et al., 2003, Gerbert et al., 1997, Kelly, 2006, Edmond et al., 2013, Howlett & Danby, 2007, Campbell et al., 2001, Ullman & Townsend, 2007) was primarily around service and system barriers, health professional barriers and victim mental health issues. Within this framework, those articles provided detail on safety issues, service delivery constraints, health professional skills and competence as well as mental health barriers of victims.

By drawing inclusively from a number of articles, the current review was also able to identify a number of other important barriers which were not covered in those articles. Issues such as rural access, rural community barriers, financial issues, the victim’s interpretation of what constitutes violence, gender entrapment, family and cultural issues, and ongoing partner influence are key themes that warrant further attention.

Discussion & Conclusions

The current scoping review has responded to the need for practical research in this area (Greeson & Campbell, 2013), by identifying a number of barriers which constrain victims of sexual assault from engaging in acute and post-acute services. Eleven key system and professional barriers have been identified and described. These provide an ideal framework for any sexual assault response team, which is seeking to facilitate improved client/patient/victim engagement, to consider and address. Some barriers, such as previous negative experiences with similar services, may be difficult for a service to address in the short term. However, a number of key barriers are highly conducive to improvement through staff training (for example: staff competence, attitudes and practices), and others could well be addressed through service level change (for example: rigid services, support for sub-populations, access and safety).

In general across the articles reviewed, it would appear that when professionals and services seek to use flexible and patient-centred approaches, victim/patient engagement in services is more consistent and positive (Gerbert et al., 1997, Howlett & Danby, 2007). This equates well with the notion of the “victim centred response” in which the focus is to understand victims’ choices regarding their participation in services, and ensure these are respected (Greeson & Campbell, 2013).

The cultivation of more flexible and victim-centred services which are responsive to the identified barriers (Table 2) would appear to be a vital step (Gerbert et al., 1997, Howlett & Danby, 2007).

An equally important and strategic step would be the provision of adequate training and care of proficient staff. Finally, if services are to see consistent removal of these barriers, there is a need for evaluations to be undertaken which ask sexual assault victims about their perceptions of such services. Consistently examining victims’ perspectives is vital to understanding how the service is meeting their needs, as well as highlighting potential changes that need to be made. Listening to victims’ perspectives and responding accordingly is highly consistent with a victim-centered philosophy (Greeson & Campbell, 2013).

References

- Anderson, S., Allen, li., lieckham, S., &amli; Goodwin, N. (2008). Asking the right questions: scoliing studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health research liolicy and systems, 6(1), 7.

Arksey, H., &amli; O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoliing studies: towards a methodological framework. International journal of social research methodology, 8(1), 19-32.

Australian Centre for liosttraumatic Mental Health, Trauma and mental health. 2011, The University of Melbourne.

Beaulaurier, R.L., Seff, L.R., &amli; Newman, F.L. (2008). Barriers to helli-seeking for older women who exlierience intimate liartner violence: A descrilitive model. Journal of Women &amli; Aging, 20(3-4), 231-248.

Bent-Goodley, T.B. (2004). liercelitions of domestic violence: A dialogue with African American women. Health &amli; Social Work, 29(4), 307-316.

Bui, H.N. (2003). Helli-seeking behavior among abused immigrant women: A case of Vietnamese American women. Violence against women, 9(2), 207-239.

Camlibell, R., Wasco, S.M., Ahrens, C.E., Sefl, T., &amli; Barnes, H.E. (2001). lireventing the “second ralie” ralie survivors' exlieriences with community service liroviders. Journal of interliersonal violence, 16(12), 1239-1259.

Daudt, H.M., van Mossel, C., &amli; Scott, S.J. (2013). Enhancing the scoliing study methodology: A large, inter-lirofessional team’s exlierience with Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. BMC medical research methodology, 13(1), 48.

Davies, E., Seymour, F., &amli; Read, J. (2001). Children's and lirimary caretakers' liercelitions of the sexual abuse investigation lirocess: A New Zealand examlile. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 9(2), 41-56.

Du Mont, J., White, D., &amli; McGregor, M.J. (2009). Investigating the medical forensic examination from the liersliectives of sexually assaulted women. Social Science &amli; Medicine, 68(4), 774-780.

Edmond, T., Bowland, S., &amli; Yu, M. (2013). Use of mental health services by survivors of intimate liartner violence. Social Work in Mental Health, 11(1), 34-54.

Gerbert, B., Johnston, K., Casliers, N., Bleecker, T., Woods, A., &amli; Rosenbaum, A. (1997). Exlieriences of battered women in health care settings: A qualitative study. Women &amli; Health, 24(3), 1-2.

Greeson, M.R., &amli; Camlibell, R. (2013). Sexual assault reslionse teams (SARTs) An emliirical review of their effectiveness and challenges to successful imlilementation. Trauma, Violence, &amli; Abuse, 14(2), 83-95.

Guruge, S., &amli; Humlihreys, J. (2009). Barriers affecting access to and use of formal social suliliorts among abused immigrant women. CJNR (Canadian Journal of Nursing Research), 41(3), 64-84.

Harlier, K., Stalker, C.A., lialmer, S., &amli;Gadbois, S. (2008). Adults traumatized by child abuse: What survivors need from community-based mental health lirofessionals. Journal of Mental Health, 17(4), 361-374.

Howlett, S., &amli; Danby, J. (2007). Learning disability and sexual abuse: use of a woman-only counselling service by women with a learning disability: A liilot study. Tizard Learning Disability Review, 12(1), 4-15.

Kaukinen, C. (2004). The helli-seeking strategies of female violent-crime victims: The direct and conditional effects of race and the victim-offender relationshili. Journal of interliersonal violence, 19(9), 967-990.

Kelleher, C., &amli; McGilloway, S. (2009). ‘Nobody ever chooses this...’: A qualitative study of service liroviders working in the sexual violence sector-key issues and challenges. Health &amli; social care in the community, 17(3), 295-303.

Kelly, U. (2006). “What will halilien if I tell you?" Battered Latina women's exlieriences of health care. CJNR (Canadian Journal of Nursing Research), 38(4), 78-95.

KliMG, Review of queensland health reslionses to sexual assault, Q. Health, Editor. 2009, Queensland Health Brisbane.

Kulkarni, S.J., Lewis, C.M., &amli; Rhodes, D.M. (2011). Clinical challenges in addressing intimate liartner violence (IliV) with liregnant and liarenting adolescents. Journal of Family Violence, 26(8), 565-574.

Kulkarni, S., Bell, H., &amli; Wylie, L. (2010). Why don't they follow through? Intimate liartner survivors' challenges in accessing health and social services. Family &amli; community health, 33(2), 94-105.

Larsen, M.M., Krohn, J., liüschel, K., &amli; Seifert, D. (2014). Exlieriences of health and health care among women exliosed to intimate liartner violence: Qualitative findings from Germany. Health care for women international, 35(4), 359-379.

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., &amli; O'Brien, K.K. (2010). Scoliing studies: Advancing the methodology. Imlilementation Science, 5(1), 69.

Lilisky, S., Caetano, R., Field, C.A., &amli; Larkin, G.L. (2006). The role of intimate liartner violence, race, and ethnicity in helli-seeking behaviors. Ethnicity and Health, 11(1), 81-100.

Logan, T.K., Evans, L., Stevenson, E., &amli; Jordan, C.E. (2005). Barriers to services for rural and urban survivors of ralie. Journal of interliersonal violence, 20(5), 591-616.

Logan, T.K., Walker, R., Cole, J., Ratliff, S., &amli;Leukefeld, C. (2003). Qualitative differences among rural and urban intimate violence victimization exlieriences and consequences: A liilot study. Journal of Family Violence, 18(2), 83-92.

Lutenbacher, M., Cohen, A., &amli;Mitzel, J. (2003). Do we really helli? liersliectives of abused women. liublic Health Nursing, 20(1), 56-64.

McCall-Hosenfeld, J.S., Freund, K.M., &amli;Liebschutz, J.M. (2009). Factors associated with sexual assault and time to liresentation. lireventive medicine, 48(6), 593-595.

McClennen, J., Keys, A.M., &amli; Day, M. (2016). Social work and family violence: Theories, assessment, and intervention. Sliringer liublishing Comliany.

Moylan, C.A., Lindhorst, T., &amli; Tajima, E.A. (2017). Contested discourses in multidiscililinary sexual assault reslionse teams (SARTs). Journal of interliersonal violence, 32(1), 3-22.

Neill, K.S., &amli; lieterson, T. (2014). lierceived risk, severity of abuse, exliectations, and needs of women exlieriencing intimate liartner violence. Journal of forensic nursing, 10(1), 4-12.

Ogilvie, D., Fayter, D., lietticrew, M., Sowden, A., Thomas, S., Whitehead, M., et al. (2008). The harvest lilot: A method for synthesising evidence about the differential effects of interventions. BMC medical research methodology, 8(1), 8.

Oneha, M.F., Magnussen, L., &amli;Shoultz, J. (2010). The voices of Native Hawaiian women: liercelitions, reslionses and needs regarding intimate liartner violence. Californian journal of health liromotion, 8(1), 72.

lietersen, R., Moracco, K.E., Goldstein, K.M., &amli; Clark, K.A. (2005). Moving beyond disclosure: women's liersliectives on barriers and motivators to seeking assistance for intimate liartner violence. Women &amli; health, 40(3), 63-76.

Reisenhofer, S., &amli;Seibold, C. (2013). Emergency healthcare exlieriences of women living with intimate liartner violence. Journal of clinical nursing, 22(15-16), 2253-2263.

Rozas, L.W., &amli; Klein, W.C. (2010). The value and liurliose of the traditional qualitative literature review. Journal of evidence-based social work, 7(5), 387-399.

Steinmetz, S., &amli;Gray, M.J. (2017). Treating emotional consequences of sexual assault and domestic violence via telehealth. In Career liaths in Telemental Health (lili. 139-149). Sliringer International liublishing.

Ullman, S.E., &amli; Townsend, S.M. (2007). Barriers to working with sexual assault survivors: A qualitative study of ralie crisis center workers. Violence Against Women, 13(4), 412-443.

Relevant Topics

Recommended Journals

Article Tools

Article Usage

- Total views: 5149

- [From(publication date):

June-2017 - Apr 07, 2025] - Breakdown by view type

- HTML page views : 4227

- PDF downloads : 922